Key Points

Profilin 1–mediated cytoskeletal dynamics regulate platelet β1- and β3-integrin function and turnover.

Profilin 1 deficiency in platelets impairs hemostasis and results in a marked protection from arterial thrombosis.

Introduction

Platelet adhesion and aggregation at sites of vascular injury is essential for hemostasis but may also cause thrombosis.1 Firm platelet adhesion is mediated by heterodimeric receptors of the β1- and β3-integrin families, which upon activation reversibly shift to a high-affinity state and efficiently bind their ligands, most notably components of the extracellular matrix and other receptors.2-4 Binding of talin-1 (Tln1) and kindlins to the intracellular tail of the integrin β-subunit triggers the switch to the high-affinity state, whereas their dissociation results in integrin closure, the switch back to the low-affinity state.5-8 Tln1 and kindlins connect integrins to the actin cytoskeleton, thereby enabling the sensing and exertion of mechanical forces as well as regulating adhesion formation and turnover.9-12 Consistently, defects in actin-regulating proteins result in altered platelet and megakaryocyte integrin function.13-19 Furthermore, we have recently shown a critical role of twinfilin 2a (Twf2a) and the cortical cytoskeleton in regulating platelet integrin turnover in a profilin 1 (Pfn1)–dependent manner.10

The small actin-binding protein Pfn1 is central for actin dynamics by mediating the nucleotide exchange on G-actin monomers, thereby promoting filament assembly with implications for platelet biogenesis.13,20 Megakaryocyte-specific Pfn1 deficiency resulted in microthrombocytopenia because of cytoskeletal alterations and accelerated platelet clearance (supplemental Figure 1).13 However, the precise role of Pfn1 for platelet function is unknown.

Here, we report that the lack of Pfn1 in platelets (Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre) perturbs the organization of the adhesion-dependent circumferential actin network and thereby results in accelerated integrin inactivation and hence impaired platelet function in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Animals, flow cytometry, aggregation, immunostaining, adhesion under flow, clot retraction, immunoblotting, tail bleeding assay, in vivo model, Ca2+ measurements, atomic force microscopy, and statistical analyses are described in the supplemental Methods.13 Animal studies were approved by the district government of Lower Franconia (Bezirksregierung Unterfranken).

Results and discussion

Impaired inside-out integrin activation in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets

To study the role of Pfn1 in integrin function, platelet β1- and β3-integrin activation was assessed by flow cytometry at different time points. Strikingly, Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets showed impaired activation of β1- and β3-integrins (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figures 2 and 3), whereas α-granule release (assessed by P-selectin exposure; Figure 1C), as well as surface expression of β1- and β3-integrins, was only marginally altered (supplemental Figure 4).

Pfn1 deficiency impairs platelet integrin function. Activation of platelet αIIbβ3- (JON/A-phycoerythrin [PE]) (A) and β1-integrins (9EG7-FITC) (B), as well as α-granule release (anti-P-selectin-FITC) (C) in response to different agonists were assessed by flow cytometry after 15 minutes. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. Antibodies were present throughout the stimulation to assess maximal integrin activation at the respective time points. Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 6 vs 6). Impaired platelet αIIbβ3- and α2β1-integrin function was further revealed by flow cytometry assessing platelet fibrinogen binding (samples were stimulated for 10 minutes and Mn2+ served as activation-independent positive control) (D) and aggregation responses to different agonists (E). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). Aggregation traces are representative of at least 6 animals per group. Assessment of platelet (F) adhesion and aggregate formation under flow (1000/s) on collagen I (70 μg/mL) (G) of WT and platelet count-adjusted Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre samples. Values are mean ± SD (n = 12 vs 12). (H) Platelet clot retraction was determined over time in response to 5 U/mL thrombin and residual serum volume was quantified after 180 minutes at the end of the observation period. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). In vivo, Pfn1 deficiency resulted in impaired hemostasis as assessed by a tail bleeding time assay (n = 9 vs 9) (I) and a protection from arterial thrombosis upon induction of a mechanical injury in the abdominal aorta (n = 7 vs 6) (J). Basal [Ca2+]i (n = 17 vs 19) (K) and maximal increase of [Ca2+]i after stimulation with thrombin (Thr), collagen-related peptide (CRP), or the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (TG) of at least 9 vs 11 animals (L). Experiments were performed in the presence of 1 mM extracellular Ca2+. Each symbol in panels I and J represents 1 animal. Horizontal lines in panel I represent mean. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; CVX, convulxin; Mn2+, manganese; Rest, resting; Rhd, rhodocytin; U46, stable thromboxane A2 analog U46619. Unpaired Student t test (A-D, F-I, and K-L) and Fisher’s exact test (J) were used to assess statistical differences between the groups: ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05. NS, nonsignificant.

Pfn1 deficiency impairs platelet integrin function. Activation of platelet αIIbβ3- (JON/A-phycoerythrin [PE]) (A) and β1-integrins (9EG7-FITC) (B), as well as α-granule release (anti-P-selectin-FITC) (C) in response to different agonists were assessed by flow cytometry after 15 minutes. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. Antibodies were present throughout the stimulation to assess maximal integrin activation at the respective time points. Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 6 vs 6). Impaired platelet αIIbβ3- and α2β1-integrin function was further revealed by flow cytometry assessing platelet fibrinogen binding (samples were stimulated for 10 minutes and Mn2+ served as activation-independent positive control) (D) and aggregation responses to different agonists (E). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). Aggregation traces are representative of at least 6 animals per group. Assessment of platelet (F) adhesion and aggregate formation under flow (1000/s) on collagen I (70 μg/mL) (G) of WT and platelet count-adjusted Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre samples. Values are mean ± SD (n = 12 vs 12). (H) Platelet clot retraction was determined over time in response to 5 U/mL thrombin and residual serum volume was quantified after 180 minutes at the end of the observation period. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). In vivo, Pfn1 deficiency resulted in impaired hemostasis as assessed by a tail bleeding time assay (n = 9 vs 9) (I) and a protection from arterial thrombosis upon induction of a mechanical injury in the abdominal aorta (n = 7 vs 6) (J). Basal [Ca2+]i (n = 17 vs 19) (K) and maximal increase of [Ca2+]i after stimulation with thrombin (Thr), collagen-related peptide (CRP), or the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (TG) of at least 9 vs 11 animals (L). Experiments were performed in the presence of 1 mM extracellular Ca2+. Each symbol in panels I and J represents 1 animal. Horizontal lines in panel I represent mean. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; CVX, convulxin; Mn2+, manganese; Rest, resting; Rhd, rhodocytin; U46, stable thromboxane A2 analog U46619. Unpaired Student t test (A-D, F-I, and K-L) and Fisher’s exact test (J) were used to assess statistical differences between the groups: ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05. NS, nonsignificant.

The β3-integrin activation defect was further revealed by a decreased binding of Alexa-F488-conjugated fibrinogen to Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets at all tested time points in response to agonist stimulation (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 5). Of note, irreversible fibrinogen binding was almost indistinguishable between WT and Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets, suggesting that receptor clustering is not altered by the Pfn1 deficiency (supplemental Figure 6). Surprisingly, aggregation responses of Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets were only slightly affected by the impaired integrin activation (Figure 1A,D-E; supplemental Figures 2, 5, and 7), whereas the adhesion and aggregate formation of Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets on collagen I under flow were markedly reduced (Figure 1F-G; supplemental Figure 8). We speculate that the reduced integrin function of Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets is still sufficient to mediate platelet aggregation under static conditions, but insufficient to resist shear forces generated under flow because of an impaired connection of integrins and the actin cytoskeleton.

Pfn1 deficiency impairs integrin outside-in signaling

Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets displayed impaired integrin outside-in signaling, as evidenced by almost abolished lamellipodia (WT, 58.0% ± 3.0% vs Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre, 18.5% ± 4.3%; ***P < .001) and filopodia formation (WT, 46.9% ± 1.4% vs Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre, 11.6% ± 1.5% ; ***P < .001) when allowed to spread on fibrinogen (supplemental Figure 9).13,21 Similarly, Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets showed severely delayed and less effective clot retraction (Figure 1H), further reflecting impaired integrin function and actin dynamics.10,13 Because Pfn1 is an effector of the RhoA/Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) pathway, these findings are in agreement with reports on RhoA-deficient platelets that show abolished clot retraction.22 Furthermore, the strongly impaired filopodia and lamellipodia formation of Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets suggests that Pfn1 acts as a key effector in actin dynamics and integrin function downstream of Rho guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases).23

Pfn1 is critical for hemostasis and thrombosis

In agreement with the in vitro data, Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre mice displayed prolonged bleeding times (13.3 ± 2.7 minutes) as compared with controls (7.2 ± 2.3 minutes). Two out of 10 Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre mice even failed to cease bleeding within the observation period (Figure 1I). Consistently, upon induction of arterial thrombosis by mechanical injury of the abdominal aorta, all control mice formed occlusive thrombi (4.0 ± 1.2 minutes), whereas 5 out of 6 Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre mice did not form stable occlusions (Figure 1J; supplemental Figure 10), thus revealing Pfn1 as a critical factor for platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis. These defects appeared to be caused by the defective integrin function of Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets, because degranulation was normal (Figure 1C) and alterations in coagulation factors or other cell types could be excluded because we capitalized on a megakaryocyte- and platelet-specific conditional knockout mouse model.

Altered integrin and Tln1 localization in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets

Ca2+ signaling is essential for platelet integrin activation; however, contrary to a functional impairment we found an increased basal [Ca2+]i and enhanced store-operated Ca2+ entry in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets (Figure 1K-L). This was most likely due to impaired actin dynamics in the absence of Pfn1,13 because inhibition of activation-dependent actin-polymerization was shown to increase store-operated Ca2+ entry.24

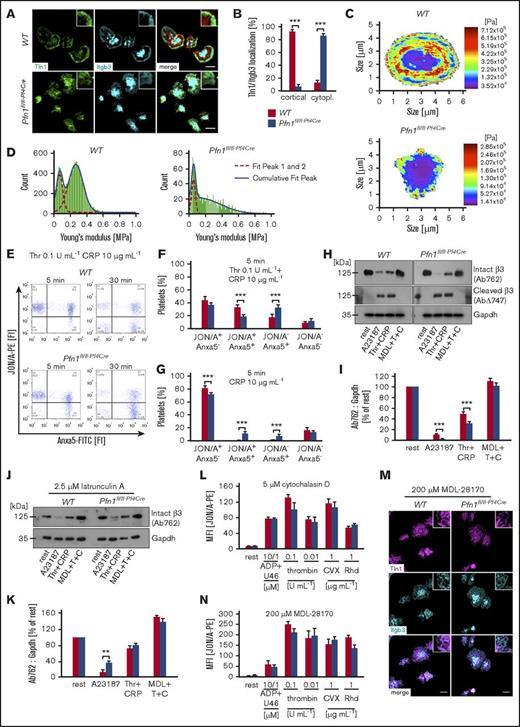

Besides Ca2+ signaling, Tln1 recruitment to β-integrin tails represents a key step in integrin activation. Whereas in spread control platelets Tln1 and β3-integrins colocalized at the cell cortex, we found a diffuse colocalization pattern in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets, suggesting impaired β3-integrin localization or Tln1 recruitment as cause for the observed defects (Figure 2A-B). Strikingly, the localization of Tln1 and β3-integrins at the cell cortex of control platelets coincided with a high cellular stiffness, reminiscent of the cortical cytoskeleton.20 Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets, however, only displayed focal spots of increased stiffness on the cell cortex, strongly resembling the random colocalization pattern of Tln1, β3-integrins, and the disrupted cortical actin cytoskeleton (Figure 2A-D; supplemental Figure 11). These results indicate that the impaired cytoskeletal dynamics in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets may account for the altered recruitment to, or stabilization of, integrins and/or Tln1 at the leading edge of spread platelets.9-13

Accelerated integrin inactivation in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Creplatelets. (A) β3-integrin (Itgb3) localization and recruitment of talin-1 (Tln1) to β-integrin tails was assessed by immunostaining and confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, 100×/1.4 oil STED White objective, Leica Microsystems) of fibrinogen-spread platelets (n = 6 vs 6). Scale bars, 3 μm. (B) Assessment of the Tln1 and β3-integrin distribution pattern in at least 70 platelets of 6 animals per group. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). Representative heat maps (C) and histograms (D) of the cellular stiffness measured by atomic force microscopy on fibrinogen-spread platelets of 5 animals per group. Washed platelets were stimulated for 5 or 30 minutes with thrombin (Thr, T) and collagen-related peptide (CRP, C) (E-F) or CRP alone (G). Activation of αIIbβ3-integrins and phosphatidylserine exposure on the outer leaflet of the platelet membrane were determined by adding JON/A-PE antibody and Anxa5-FITC protein 5 minutes prior to the end of the incubation time. Analysis was performed by flow cytometry. Flow cytometry plots are representative of at least 6 animals per group. (F-G) Percentage of platelets per quadrant (Q); Q1, JON/A+ Anxa5− (upper left); Q2, JON/A+ Anxa5+ (upper right); Q3, JON/A− Anxa5+ (lower right); Q4, JON/A− Anxa5− (lower left). Values are mean ± SD of 6 vs 7 animals. Resting (H-I) or 2.5 μM latrunculin A-pretreated (J-K) platelets were left untreated or preincubated for 10 minutes in the presence of the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 (200 μM). Subsequently, samples were stimulated with the calcium ionophore A23187 (10 μM) or thrombin (0.1 U/mL) and CRP (10 μg/mL), lysed, and processed for immunoblotting. Full-length (Ab762) and calpain-cleaved (AbΔ747) β3-integrin were probed with the respective antibodies and analyzed by densitometry. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) served as control. Values are mean ± SD of 6 vs 7 animals. (H,J) Immunoblots are representative of at least 6 animals per group. Platelets were either pretreated with 5 μM of the actin polymerization inhibiting drug cytochalasin D (L) or 200 μM of the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 (M-N). Subsequently, the activation and localization of β3-integrin and Tln1 was assessed by flow cytometry (L,N) or immunostaining and confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, 100×/1.4 oil STED White objective, Leica Microsystems) on fibrinogen-spread platelets (M). Values are mean ± SD of 4 vs 4 animals. Unpaired Student t test was used to assess statistical differences between the groups: ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

Accelerated integrin inactivation in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Creplatelets. (A) β3-integrin (Itgb3) localization and recruitment of talin-1 (Tln1) to β-integrin tails was assessed by immunostaining and confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, 100×/1.4 oil STED White objective, Leica Microsystems) of fibrinogen-spread platelets (n = 6 vs 6). Scale bars, 3 μm. (B) Assessment of the Tln1 and β3-integrin distribution pattern in at least 70 platelets of 6 animals per group. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). Representative heat maps (C) and histograms (D) of the cellular stiffness measured by atomic force microscopy on fibrinogen-spread platelets of 5 animals per group. Washed platelets were stimulated for 5 or 30 minutes with thrombin (Thr, T) and collagen-related peptide (CRP, C) (E-F) or CRP alone (G). Activation of αIIbβ3-integrins and phosphatidylserine exposure on the outer leaflet of the platelet membrane were determined by adding JON/A-PE antibody and Anxa5-FITC protein 5 minutes prior to the end of the incubation time. Analysis was performed by flow cytometry. Flow cytometry plots are representative of at least 6 animals per group. (F-G) Percentage of platelets per quadrant (Q); Q1, JON/A+ Anxa5− (upper left); Q2, JON/A+ Anxa5+ (upper right); Q3, JON/A− Anxa5+ (lower right); Q4, JON/A− Anxa5− (lower left). Values are mean ± SD of 6 vs 7 animals. Resting (H-I) or 2.5 μM latrunculin A-pretreated (J-K) platelets were left untreated or preincubated for 10 minutes in the presence of the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 (200 μM). Subsequently, samples were stimulated with the calcium ionophore A23187 (10 μM) or thrombin (0.1 U/mL) and CRP (10 μg/mL), lysed, and processed for immunoblotting. Full-length (Ab762) and calpain-cleaved (AbΔ747) β3-integrin were probed with the respective antibodies and analyzed by densitometry. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) served as control. Values are mean ± SD of 6 vs 7 animals. (H,J) Immunoblots are representative of at least 6 animals per group. Platelets were either pretreated with 5 μM of the actin polymerization inhibiting drug cytochalasin D (L) or 200 μM of the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 (M-N). Subsequently, the activation and localization of β3-integrin and Tln1 was assessed by flow cytometry (L,N) or immunostaining and confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5, 100×/1.4 oil STED White objective, Leica Microsystems) on fibrinogen-spread platelets (M). Values are mean ± SD of 4 vs 4 animals. Unpaired Student t test was used to assess statistical differences between the groups: ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

Accelerated integrin inactivation in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets

We recently showed that the organization of the circumferential actin-cytoskeleton modulates calpain-mediated inactivation of activated platelet β3-integrins and thereby also controls their localization.10 Based on this, together with the disrupted cortical actin-cytoskeleton and the enhanced Ca2+ signaling in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets, we hypothesized that Tln1 and β3-integrins might be more prone to calpain-mediated cleavage and that this could account for the altered localization and impaired function of integrins in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets. In support of this, we found a significantly increased percentage of phosphatidylserine-positive Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets with inactivated integrins (JON/A− Anxa5+; lower right quadrant) after both 5 minutes (WT, 18.2% ± 5.6% vs Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre, 32.6% ± 4.1%; ***P < .001) and 30 minutes (WT, 50.9% ± 8.7% vs Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre, 65.6% ± 4.3%; **P < .01) upon stimulation with thrombin and CRP (Figure 2E-F; supplemental Figure 12A,C). Similar observations were made upon stimulation with CRP alone, but not when using the A23187 ionophore that efficiently induces phosphatidylserine exposure without integrin activation (Figure 2G; supplemental Figure 12A-B,D-F). Remarkably, stimulated Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets displayed an increased loss of β3-integrin, Tln1, and filamin A as compared with control that could be fully rescued by chemical inhibition of calpain or actin assembly, suggesting that enhanced calpain-mediated integrin inactivation due to an insufficient cytoskeletal linkage may account for the observed defects in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets (Figure 2H-K; supplemental Figures 13 and 14). In support of this, pretreatment of platelets with the actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D overall reduced β3-integrin activation but, most importantly, diminished the differences between WT and Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets (Figures 1A and 2L; supplemental Figure 2). Moreover, chemical inhibition of calpain improved the spreading of Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets and restored the localization as well as activation of β3-integrins and Tln (Figure 2M-N).

In summary, these results revealed that the defective organization of the cortical cytoskeleton in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets leads to accelerated integrin inactivation and hence impaired platelet function. Based on the patchy colocalization pattern of Tln1, β3-integrins, and the disrupted cytoskeleton in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets, it is tempting to speculate that Pfn1 might act as an organizer of the adhesion-dependent, circumferential actin network, thereby linking integrins to the underlying cytoskeleton and limiting calpain-mediated integrin inactivation.24 In support of this, we have found increased Pfn1 activity in Twf2a−/− platelets, which resulted in a thickened cortical cytoskeleton and sustained integrin activation due to limited calpain-mediated inactivation.10 However, an increased calpain activity due to the impaired actin dynamics in Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre platelets also needs to be considered.

In summary, our findings highlight a central role of Pfn1-mediated actin rearrangements for normal platelet integrin function and turnover with implications for hemostasis and thrombosis.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stefanie Hartmann for excellent technical assistance and the microscopy platform of the Bioimaging Center (Rudolf Virchow Center) for providing technical infrastructure and support.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB688 and NI 556/11-1) (B.N.). S. Stritt was supported by a research fellowship of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (STR 1538/1-1) and a nonstipendiary long-term fellowship of the European Molecular Biology Organization (ALTF 86-2017). M.B. is supported by an Emmy Noether grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BE5084/3-1).

Authorship

Contribution: S. Stritt designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; I.B. performed experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the revised manuscript; S.B., S. Sorrentino, K.T.S., J.H., J.H.H., A.B., and M.B. performed experiments, analyzed data, and commented on the manuscript; H.S. and O.M. analyzed data and commented on the manuscript; J.V., F.G.-I., and X.D. provided vital reagents and commented on the manuscript; and B.N. designed and supervised research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S. Stritt is Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Correspondence: Bernhard Nieswandt, Institute of Experimental Biomedicine, University Hospital and Rudolf Virchow Centre, University of Würzburg, Josef-Schneider-Str 2, 97080 Würzburg, Germany; e-mail: bernhard.nieswandt@virchow.uni-wuerzburg.de.

References

Author notes

S. Stritt and I.B. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Pfn1 deficiency impairs platelet integrin function. Activation of platelet αIIbβ3- (JON/A-phycoerythrin [PE]) (A) and β1-integrins (9EG7-FITC) (B), as well as α-granule release (anti-P-selectin-FITC) (C) in response to different agonists were assessed by flow cytometry after 15 minutes. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. Antibodies were present throughout the stimulation to assess maximal integrin activation at the respective time points. Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 6 vs 6). Impaired platelet αIIbβ3- and α2β1-integrin function was further revealed by flow cytometry assessing platelet fibrinogen binding (samples were stimulated for 10 minutes and Mn2+ served as activation-independent positive control) (D) and aggregation responses to different agonists (E). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). Aggregation traces are representative of at least 6 animals per group. Assessment of platelet (F) adhesion and aggregate formation under flow (1000/s) on collagen I (70 μg/mL) (G) of WT and platelet count-adjusted Pfn1fl/fl-Pf4Cre samples. Values are mean ± SD (n = 12 vs 12). (H) Platelet clot retraction was determined over time in response to 5 U/mL thrombin and residual serum volume was quantified after 180 minutes at the end of the observation period. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 vs 6). In vivo, Pfn1 deficiency resulted in impaired hemostasis as assessed by a tail bleeding time assay (n = 9 vs 9) (I) and a protection from arterial thrombosis upon induction of a mechanical injury in the abdominal aorta (n = 7 vs 6) (J). Basal [Ca2+]i (n = 17 vs 19) (K) and maximal increase of [Ca2+]i after stimulation with thrombin (Thr), collagen-related peptide (CRP), or the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (TG) of at least 9 vs 11 animals (L). Experiments were performed in the presence of 1 mM extracellular Ca2+. Each symbol in panels I and J represents 1 animal. Horizontal lines in panel I represent mean. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; CVX, convulxin; Mn2+, manganese; Rest, resting; Rhd, rhodocytin; U46, stable thromboxane A2 analog U46619. Unpaired Student t test (A-D, F-I, and K-L) and Fisher’s exact test (J) were used to assess statistical differences between the groups: ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05. NS, nonsignificant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/2/9/10.1182_bloodadvances.2017014001/3/m_advances014001f1.jpeg?Expires=1767928544&Signature=cvmSVukKyM4NmT3gyim2-Ade7vgkRARlj-fAhvDG1iXNatQALm02aG4d5X3SNeQOXIdToN3dJ4mL4pEVQcFvRXUT7-YnB3gPQWJszxRK6wl40hUPV2xa-XKCHZfdsFcQ5GZ--zAa0NdA6rNrdu-r9yKdjZIT4zcFkSXBzSqWKhAaGCLh1fi85OdZp4Kpo9qsgGzu4dgz-WfblY2hUjHpPofNPEvIrGLsA4sqsDrTqCH2LQnYMu1B7jnU0VGPVV876EsVdeodP3wEkxc-UqtliCBFfGoVM8sdM90IvNROMgeI2q-q-grTpe5DIcTdPYRsjBBIXJZZt4opa3K846S5oA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)