Key Points

Biolayer interferometry and Michaelis–Menten enzyme kinetics support the formation of the active Xase complex on lipid nanodiscs.

SAXS-derived model of the nanodisc-bound Xase complex indicates contacts between fVIIIa A2/A3/C2 domains and fIXa catalytic/Gla domains.

Abstract

The intrinsic tenase (Xase) complex, formed by factors (f) VIIIa and fIXa, forms on activated platelet surfaces and catalyzes the activation of factor X to Xa, stimulating thrombin production in the blood coagulation cascade. The structural organization of the membrane-bound Xase complex remains largely unknown, hindering our understanding of the structural underpinnings that guide Xase complex assembly. Here, we aimed to characterize the Xase complex bound to a lipid nanodisc with biolayer interferometry (BLI), Michaelis–Menten kinetics, and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Using immobilized lipid nanodiscs, we measured binding rates and nanomolar affinities for fVIIIa, fIXa, and the Xase complex. Enzyme kinetic measurements demonstrated the assembly of an active enzyme complex in the presence of lipid nanodiscs. An ab initio molecular envelope of the nanodisc-bound Xase complex allowed us to computationally model fVIIIa and fIXa docked onto a flexible lipid membrane and identify protein–protein interactions. Our results highlight multiple points of contact between fVIIIa and fIXa, including a novel interaction with fIXa at the fVIIIa A1–A3 domain interface. Lastly, we identified hemophilia A/B-related mutations with varying severities at the fVIIIa/fIXa interface that may regulate Xase complex assembly. Together, our results support the use of SAXS as an emergent tool to investigate the membrane-bound Xase complex and illustrate how mutations at the fVIIIa/fIXa dimer interface may disrupt or stabilize the activated enzyme complex.

Introduction

Factor VIII (fVIII) is a procoagulant glycoprotein secreted into the bloodstream as a heterodimer with the domain architecture A1-A2-B/a3-A3-C1-C2 in a tight complex with von Willebrand factor (vWf) to inhibit premature fVIII clearance.1,2 Proteolytic cleavage by thrombin releases vWf and generates the activated fVIII (fVIIIa) A1/A2/A3-C1-C2 heterotrimer,3,4 which binds to activated platelet surfaces through several hydrophobic loops in the C1 and C2 domains.5-9 Binding to activated factor IX (fIXa), a trypsin-like serine protease, forms the intrinsic tenase (Xase) complex, which catalyzes the activation of factor X (fX), enhancing thrombin turnover and clot formation.10 FIXa is a heterodimer of its light chain, composed of an N-terminal γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) domain11,12 and 2 epidermal growth factor-like (EGF-1 and EGF-2) domains, and heavy chain, which carries the catalytic domain.13 Inactivation of the Xase complex occurs by dissociation of the fVIIIa A2 domain, proteolytic degradation by activated protein C, and inhibition of fIXa by antithrombin III.14,15

In the absence of fVIIIa and phospholipids, fIXa retains minimal activity due to the autoinhibitory 99-loop, which sterically blocks occupation of the active site and is stabilized by multiple intramolecular contacts.10,16-18 Binding to fVIIIa and fX on lipid membranes is hypothesized to rearrange the 99-loop, increasing kcat by ∼103-fold and reducing Km by ∼103-fold.19,20 Individuals with hemophilia A or B, caused by a mutation to fVIII or fIX, respectively, have reduced capacity to form the Xase complex and significantly lowered clotting efficiency.2,21 Conversely, several gain-of-function mutations to fIX are proposed to stabilize the Xase complex and have been identified in patients with deep vein thrombosis,22-24 making the Xase complex a suitable target for treating thrombotic disorders.25-28

Structural studies on the Xase complex have proposed multiple binding sites between the fVIIIa A2, A3, and C2 domains and fIXa catalytic and Gla domains.29-35 A putative allosteric network in the fIXa catalytic domain between the 99-loop and a cluster of solvent-exposed helices, collectively described as exosite II, has been proposed to modulate the conformation of the 99-loop36,37 and is a potential binding site for fVIIIa.31,38 The crystal structure of the prothrombinase complex, formed by factors Va/Xa, which are homologous to fVIIIa/fIXa, respectively, suggests the catalytic domain docks onto the A2 and A3 domains.39 Computational models of the Xase complex have provided broad structural analyses of how fVIIIa docks onto fIXa and promotes binding factor X.40-42 However, a lack of biochemical information on the complete lipid-bound Xase complex in solution hinders a mechanistic understanding of how the enzyme complex is formed.

In this study, we characterized the binding kinetics and solution structure of the Xase complex bound to a lipid nanodisc (Xase:ND). Using biolayer interferometry (BLI), we calculated nanomolar affinity between fVIIIa/fIXa and immobilized nanodiscs, as well as association and dissociation rate constants. Michaelis–Menten kinetic measurements indicated the formation of the active Xase complex in the presence of lipid nanodiscs. A molecular envelope was calculated through small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), allowing us to perform a combination of computational studies to determine a working model of the Xase:ND complex in solution. In addition to supporting previously proposed intermolecular contacts, our results identified a novel interaction between the fVIIIa A1/A3 domain interface and fIXa EGF-1 domain. These findings allowed us to speculate on hemophilia A- and B-related mutations that may disrupt the formation of the Xase complex.

Materials and methods

Proteins

A bioengineered human/porcine chimera of B-domain deleted fVIII termed ET3i43,44 was activated using a Thrombin Cleavage Capture Kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. EGRck-active site-blocked human fIXa was purchased from Haematologic Technologies. The plasmid encoding for membrane scaffold protein MSP1D1 was purchased from AddGene.45

Preparation of lipid nanodiscs

Lipid nanodiscs were assembled as previously described.46-48 Briefly, MSP1D1 was expressed in BL21(DE3) bacterial cells and purified using Ni2+-affinity resin. The His6-tagged protein was dialyzed into Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (20 mM tris; pH, 8; 100 mM NaCl; 0.5 mM EDTA), concentrated to 10 mg/mL (400 µM), snap-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. Lipids were prepared as an 80:20 molar ratio of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (Avanti Polar Lipids), respectively, at a working concentration of 6 mM in TBS supplemented with 100 mM cholate. MSP1D1 and lipids were mixed at a 1:47 molar ratio, respectively, with 20 mM cholate and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. To initiate the assembly of lipid nanodiscs, 0.5 mL of activated BioBeads (BioRad) were added to the sample and incubated for 2.5 hours. BioBeads were removed using a 0.22 µm spin filter, and nanodiscs were purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 Increase 10/300; GE Healthcare) with TBS as the running buffer. A single peak was obtained at 13 mL retention volume. Fractions were pooled, concentrated to 10 µM, and stored at 4°C.45,49

BLI measurements

Binding kinetics and affinities were measured on a BLItz (ForteBio) biosensor at room temperature. Anti-penta–HIS BLI tips (ForteBio) were activated in HEPES-buffered saline (20 mM HEPES; pH, 7.4; 100 mM NaCl; 5 mM CaCl2) for 10 minutes and loaded with 4 µL of 400 nM His6-tagged nanodiscs for 60 seconds to establish a baseline. After washing in buffer, association and dissociation steps were observed over 90 seconds for fVIIIa, fIXa, and Xase (1:1, fVIIIa:fIXa) across a serial dilution (12.5-1600 nM). Binding curves were generated by GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using a global fit analysis and 1:1 binding mode from an average of 3 or more independent BLI experiments to determine association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates. The apparent dissociation constant (KD) was defined as the ratio koff/kon rather than plotting the binding response as a function of titrant concentration as the latter method yielded poorer fitting, most likely due to excluding the koff rate.50

Determination of Michaelis–Menten kinetics

Enzyme activities were measured as previously described.51-53 Briefly, reaction mixtures containing buffer (10 mM tris; pH, 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 6.25 mM CaCl2), thrombin (20 nM, or 0.13 U/mL), ET3i (10 nM), fIXa (1 nM), and nanodiscs (10 µM) were prewarmed to 37°C before initiating the reaction with factor X. Aliquots (20 µL) were removed at 2-minute intervals and mixed with 12.5 mM EDTA to stop the reaction. Levels of factor Xa were assessed by adding the chromogenic substrate analog S-2765 (350 µM; Diapharma Group) and measuring the absorbance at 405 nm. Concentrations of factor Xa were interpolated from a standard curve to calculate enzyme velocities and Michaelis–Menten kinetics (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

SAXS sample preparation and data collection

To form the Xase:ND complex, activated ET3i (5.3 µM) and fIXa (37.4 µM) were mixed with lipid nanodiscs (10 µM) at a 2:2:1 (fVIIIa:fIXa:ND) molar ratio. Samples of the empty nanodisc and nanodisc-bound Xase complex were buffer exchanged into HEPES-buffered saline, supplemented with 10 mM KNO3 and 1% (wt/vol) sucrose to reduce radiation damage,54 using 3 kDa MWCO spin filters. BLI binding measurements confirmed that KNO3 and sucrose did not disrupt the Xase complex from binding to lipid nanodiscs (supplemental Figure 1). Both samples were concentrated to approximately 1 mg/mL (assuming an A280 of 1.0 is equivalent to a protein concentration of 1 mg/mL) and stored at 4°C.

High-throughput SAXS data were collected on the Advanced Light Source SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, CA). Scattering intensities for each sample were collected from concentrations of 0.33, 0.66, and 1.0 mg/mL every 0.3 seconds for a total of 33 images. To ensure binding between the lipid nanodisc and Xase complex during SAXS data collection, the molar concentration of Xase was maintained above the calculated KD value. Buffer-subtracted intensities were averaged using FrameSlice (SIBYLS).

Generation of ab initio envelopes and models

Scattering intensities were merged and processed with PRIMUS55 and GNOM56 to calculate Kratky, Guinier, and P(r) distribution plots for the empty nanodisc and Xase:ND complex. Six independent ab initio molecular envelopes were generated and averaged for each sample by DAMMIN57 and DAMAVER,58 respectively. A final molecular envelope was determined by DAMFILT58 with half the input volume as the molecular cutoff.

Solution structures of MSP1D1 (PDB ID: 6CLZ)59 and lipids (PDB ID: 2N5E)60 were used as templates for modeling the empty nanodisc with SREFLEX.61 To generate a model of the nanodisc-bound Xase complex, we performed a combination of computational docking, rigid-body fitting, and flexible refinement. A complete structure of ET3i was generated by SWISS-MODEL62 to account for flexible loops absent in the crystal structure (PDB ID: 6MF0).63 Residues 1649-1689, comprising the acidic a3 domain, were removed to produce a model of activated ET3i. RosettaDock64-66 allowed for initial docking experiments between activated ET3i and fIXa (PDB ID: 1PFX). Iterative rounds of SREFLEX61 accounted for flexibility during refinement for both models, and the χ2 value was used as a metric to track refinement as calculated by FOXS.67,68

Results

Lipid-binding characteristics of fVIIIa, fIXa, and Xase

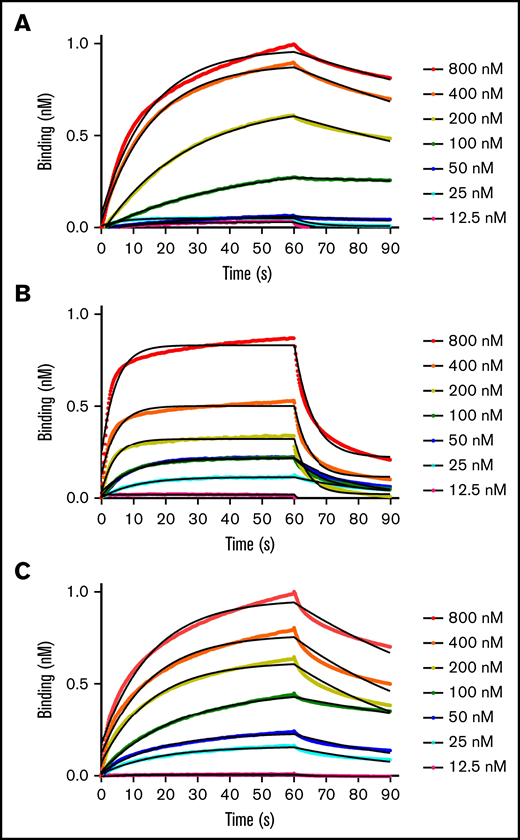

Binding kinetics and affinities between fVIIIa, fIXa, and the Xase complex to immobilized lipid nanodiscs were measured with BLI. By retaining the His6-tag on the MSP1D1 scaffold protein, we loaded anti-His6 BLI tips with nanodiscs and measured association and dissociation rates with individual coagulation factors and the Xase complex (Figure 1; Table 1). FVIIIa displayed the highest affinity for lipid membranes with a KD of 32.3 ± 6.0 nM. Remarkably, fIXa had the lowest affinity, measuring a KD of 199 ± 1.7 nM, largely due to a rapid dissociation rate of 0.0723 ± 0.003 s−1. We also confirmed that binding fIXa to lipid nanodiscs was Ca2+-dependent (supplemental Figure 2), as previously reported.19 Lastly, the Xase complex demonstrated high affinity for the immobilized nanodiscs, with a KD of 71.3 ± 4.4 nM. To our knowledge, these data represent the first reported binding affinities and rate constants between activated tenase complex proteins and lipid nanodiscs.

BLI binding measurements. Apparent binding rates and affinities for fVIIIa (A), fIXa (B), and Xase (C) (1:1, fVIIIa:fIXa) were determined by BLI using immobilized His6-tagged lipid nanodiscs. Step-corrected association and dissociation steps were measured for 60 seconds and 30 seconds, respectively, over a serial dilution of each sample (spheres). The association and dissociation binding kinetics were calculated from a global fit using a 1:1 binding analysis (black line) (GraphPad Prism 5.0) and used to calculate KD values (koff/kon). Results are summarized in Table 1.

BLI binding measurements. Apparent binding rates and affinities for fVIIIa (A), fIXa (B), and Xase (C) (1:1, fVIIIa:fIXa) were determined by BLI using immobilized His6-tagged lipid nanodiscs. Step-corrected association and dissociation steps were measured for 60 seconds and 30 seconds, respectively, over a serial dilution of each sample (spheres). The association and dissociation binding kinetics were calculated from a global fit using a 1:1 binding analysis (black line) (GraphPad Prism 5.0) and used to calculate KD values (koff/kon). Results are summarized in Table 1.

Apparent binding kinetics and affinities of fVIIIa, fIXa, and Xase with lipid nanodiscs

| . | This study . | Previously reported . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kon (×104 M−1 s−1) . | koff (×10−3 s−1) . | KD (nM) . | KD (nM) . | |

| fVIIIa | 8.62 ± 0.11 | 2.79 ± 0.55 | 32.3 ± 6.0 | 2-55,76,113 |

| fIXa | 36.3 ± 1.2 | 72.3 ± 3.0 | 199 ± 1.7 | 12-100081,114,115 |

| Xase | 14.9 ± 3.5 | 10.7 ± 0.90 | 71.3 ± 4.4 | 0.577 |

| . | This study . | Previously reported . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kon (×104 M−1 s−1) . | koff (×10−3 s−1) . | KD (nM) . | KD (nM) . | |

| fVIIIa | 8.62 ± 0.11 | 2.79 ± 0.55 | 32.3 ± 6.0 | 2-55,76,113 |

| fIXa | 36.3 ± 1.2 | 72.3 ± 3.0 | 199 ± 1.7 | 12-100081,114,115 |

| Xase | 14.9 ± 3.5 | 10.7 ± 0.90 | 71.3 ± 4.4 | 0.577 |

All data represent the average of ≥3 independent experiments with a 95% confidence interval. kon, rate of association; koff, rate of dissociation; KD, dissociation constant (koff/kon).

Lipid nanodiscs promote Xase activity

We calculated Michaelis–Menten kinetics on the Xase complex by titrating factor X in the absence and presence of lipid nanodiscs to demonstrate that the nanodisc-bound Xase complex retains catalytic activity (Figure 2; Table 2). While samples lacking the nanodiscs had a Vmax of 0.014 ± 0.009 nM fXa/min and no measurable Km,app, the addition of nanodiscs rescued Xase activity with Vmax and Km,app values of 1.03 ± 0.32 nM/min and 139 ± 76 nM, respectively, indicative of the critical role of lipid membranes in forming the active Xase complex and illustrating the novelty in studying activated procoagulant enzymes using lipid nanodiscs.

Effect of lipid nanodiscs on Xase enzymatic activity. Enzyme velocities of the Xase complex were calculated from a titration of factor X concentrations in the absence (blue circles) and presence (red circles) of lipid nanodiscs. Data represent the average of ≥2 experiments.

Effect of lipid nanodiscs on Xase enzymatic activity. Enzyme velocities of the Xase complex were calculated from a titration of factor X concentrations in the absence (blue circles) and presence (red circles) of lipid nanodiscs. Data represent the average of ≥2 experiments.

Characterization of Xase enzyme kinetics

| . | This study . | Previously reported . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km,app (nM) . | Vmax (nM fXa/min) . | kcat (min−1) . | Km,app (nM) . | Vmax (nM fXa/min) . | kcat (min−1) . | |

| −ND | N.D. | 0.014 ± 0.009 | 0.014 ± 0.009 | — | — | — |

| +ND | 139 ± 75 | 1.03 ± 0.32 | 1.03 ± 0.32 | 20-6052,77,116,117 | 1-2552,77,116,117 | 136-1740118 |

| . | This study . | Previously reported . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km,app (nM) . | Vmax (nM fXa/min) . | kcat (min−1) . | Km,app (nM) . | Vmax (nM fXa/min) . | kcat (min−1) . | |

| −ND | N.D. | 0.014 ± 0.009 | 0.014 ± 0.009 | — | — | — |

| +ND | 139 ± 75 | 1.03 ± 0.32 | 1.03 ± 0.32 | 20-6052,77,116,117 | 1-2552,77,116,117 | 136-1740118 |

Values were averaged from 2 or more independent experiments ±SE in the absence (-ND) and presence (+ND) of 10 µM nanodiscs.

Km,app, apparent Michael–Menten constant; N.D., not detectable; Vmax, maximum enzyme velocity.

Solution structure of nanodisc

We next investigated the structural characteristics of the empty nanodisc in solution using SAXS. Based on our analysis, the unloaded nanodisc adopted a compact, globular structure in solution. (Figure 3A). Scattering intensities from the Guinier region of the scatterplot were used to calculate a radius of gyration (Rg) and radius of crosssection (Rc) of 54.9 Å and 33.6 Å, respectively (Figure 3B-C; Table 3). An initial model of the empty nanodisc was composed of a flat, discoidal lipid membrane encased by a circular scaffold protein but had a poor agreement with the experimental data (Figure 3B) (χ2 = 3.64). A final model of the empty nanodisc was generated through iterative rounds of refinement with SREFLEX and fit into the ab initio molecular envelope (Figure 3D). These findings indicate that the nanodisc adopts a bent, elliptical shape in solution, in good agreement with previously reported SAXS and SANS studies.45,69 , -73 Alignment of a theoretical SAXS curve for the modeled empty nanodisc with our experimental data yielded a χ2 value of 0.26, indicating strong agreement between the 2 sets of data. Single-particle electron microscopy measurements on the empty nanodisc previously reported on the presence of stacked nanodiscs in solution under similar conditions.48 While our data support a monomeric dispersity (supplemental Figure 3), higher concentrations of the empty nanodisc may shift the equilibrium toward higher oligomeric assemblies.

SAXS analysis of empty nanodisc. (A) Kratky plot analysis. (B) Scattering curves for experimental data (red) and theoretical curves of starting model (dashed line, χ2 = 3.64) and refined model (solid line, χ2 = 0.26). (C) Pairwise distribution function. Inset depicts experimental data (red) and an indirect Fourier transform of the P(r) distribution plot (black), showing strong agreement between both sets of data. (D) (Left) An ab initio molecular envelope. (Right) Modeled empty nanodisc in sphere representation (scaffold protein: red, lipids: light orange) fit into the SAXS-derived molecular envelope.

SAXS analysis of empty nanodisc. (A) Kratky plot analysis. (B) Scattering curves for experimental data (red) and theoretical curves of starting model (dashed line, χ2 = 3.64) and refined model (solid line, χ2 = 0.26). (C) Pairwise distribution function. Inset depicts experimental data (red) and an indirect Fourier transform of the P(r) distribution plot (black), showing strong agreement between both sets of data. (D) (Left) An ab initio molecular envelope. (Right) Modeled empty nanodisc in sphere representation (scaffold protein: red, lipids: light orange) fit into the SAXS-derived molecular envelope.

SAXS parameters for ND and Xase:ND

| . | ND . | Xase:ND . |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection parameters | ||

| q range (Å−1) | 0.002-0.449 | 0.01-0.449 |

| Concentration range (mg/mL) | 0.33-1.0 | 0.33-1.0 |

| Temperature (K) | 283 | 283 |

| Structural parameters | ||

| I(0) (Guinier) | 13.32 | 59.35 |

| I(0) [P(r)] | 13.32 ± 0.9 | 59.35 ± 3.2 |

| Rg (Guinier) (Å) | 54.7 | 83.3 |

| Rg [P(r)] (Å) | 54.9 ± 6 | 83.6 ± 2.5 |

| Dmax (Å) | 213.7 | 256.8 |

| Rc (Å) | 33.6 | 42.1 |

| Porod exponent | 3.4 | 2.6 |

| . | ND . | Xase:ND . |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection parameters | ||

| q range (Å−1) | 0.002-0.449 | 0.01-0.449 |

| Concentration range (mg/mL) | 0.33-1.0 | 0.33-1.0 |

| Temperature (K) | 283 | 283 |

| Structural parameters | ||

| I(0) (Guinier) | 13.32 | 59.35 |

| I(0) [P(r)] | 13.32 ± 0.9 | 59.35 ± 3.2 |

| Rg (Guinier) (Å) | 54.7 | 83.3 |

| Rg [P(r)] (Å) | 54.9 ± 6 | 83.6 ± 2.5 |

| Dmax (Å) | 213.7 | 256.8 |

| Rc (Å) | 33.6 | 42.1 |

| Porod exponent | 3.4 | 2.6 |

SAXS analysis of the Xase:ND complex

In order to characterize the solution structure of the Xase:ND complex, SAXS data were collected over a range of concentrations (supplemental Figure 4). Analysis of the Kratky plot confirmed that the protein sample maintained an overall globular conformation (Figure 4A). A scatterplot of the merged intensities was used to calculate a P(r) distribution plot (Figure 3B-C). Differences in the P(r) distribution plots between the unloaded nanodisc and Xase:ND complex indicated the 2 samples adopted significantly different shapes. Furthermore, calculation of the Porod exponent, a metric for the compactness of a given particle, suggested the Xase:ND adopted a more extended shape than the unloaded nanodisc (Table 3). An indirect Fourier transformation of the P(r) distribution plot was performed as a quality check, yielding a smooth fit with the experimental data in the Guinier region, supporting our calculations for a theoretical Rg of 83.6 ± 2.5 Å (Table 3). Because the estimated Rc value (42.1 Å) is approximately half of the Rg, we concluded that the Xase-loaded nanodisc complex adopted an elongated, cylindrical shape. A theoretical SAXS curve was calculated for the final ab initio envelope (Figure 4D) and aligned to our SAXS data that yielded a χ2 value of 0.98. The estimated Rg and calculated SAXS envelope (Table 3; Figure 4) were consistent with 1 Xase complex bound to the nanodisc, illustrating an overall elongated shape and close association between fVIIIa and fIXa (Figure 4F).

SAXS analysis of nanodisc-bound Xase complex. (A) Kratky plot analysis. (B) Scatter curves for experimental data (blue) and theoretical model (black, χ2 = 0.25). (C) Pairwise distribution function. Inset depicts experimental data (blue) and an indirect Fourier transform of the P(r) distribution plot (black), showing strong agreement between both sets of data. (D) Ab initio bead models calculated using DAMAVER (faded) and DAMFILT (solid) and aligned by SUPCOMB. (E) Alignment of modeled tenase complex bound to a lipid nanodisc in sphere representation (fVIIIa heavy chain: dark blue; fVIIIa light chain: cyan; fIXa heavy chain: light green; fIXa light chain: dark green; scaffold protein: red; lipids: light orange) with the calculated ab initio envelope (mesh) by SUPCOMB. (F) Model of the nanodisc-bound Xase complex (fVIIIa heavy chain: dark blue; fVIIIa light chain: cyan; fIXa heavy chain: light green; fIXa light chain: dark green; scaffold protein: red; lipids: light orange).

SAXS analysis of nanodisc-bound Xase complex. (A) Kratky plot analysis. (B) Scatter curves for experimental data (blue) and theoretical model (black, χ2 = 0.25). (C) Pairwise distribution function. Inset depicts experimental data (blue) and an indirect Fourier transform of the P(r) distribution plot (black), showing strong agreement between both sets of data. (D) Ab initio bead models calculated using DAMAVER (faded) and DAMFILT (solid) and aligned by SUPCOMB. (E) Alignment of modeled tenase complex bound to a lipid nanodisc in sphere representation (fVIIIa heavy chain: dark blue; fVIIIa light chain: cyan; fIXa heavy chain: light green; fIXa light chain: dark green; scaffold protein: red; lipids: light orange) with the calculated ab initio envelope (mesh) by SUPCOMB. (F) Model of the nanodisc-bound Xase complex (fVIIIa heavy chain: dark blue; fVIIIa light chain: cyan; fIXa heavy chain: light green; fIXa light chain: dark green; scaffold protein: red; lipids: light orange).

Computational modeling of the Xase:ND complex

Modeling of the Xase:ND complex into the calculated SAXS envelope was accomplished through a combination of rigid-body fitting and flexible refinement, guided by previously reported interactions between fVIIIa and fIXa. The A2 and A3 domains of fVIIIa, specifically the 558-loop, are predicted to be in close proximity with the fIXa catalytic domain.30,31,35,36 The fVIIIa C2 domain carries a putative binding site for the fIXa Gla domain,32,33 both of which contribute to lipid membrane binding.7,12,20,74 Lastly, interdomain contacts between EGF-2 and the catalytic domain of fIXa are critical for the formation of the Xase complex and prevent dissociation between the fIXa heavy and light chains.75

Our results support multiple points of contact between fVIIIa and fIXa. The fIXa catalytic domain fits closely to the fVIIIa A2 and A3 domains. The A2 domain, specifically residues 484-489 and 555-571, is positioned near exosite II of fIXa (Figure 5A). The fIXa 99-loop, which acts as an autoinhibitory element in fIXa by blocking the nearby substrate-binding pocket, is positioned near a cleft formed by fVIIIa residues 1790-1798 and 1803-1818 of the A3 domain (Figure 5B) and may be stabilized by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Additionally, residues 2228-2240 of the fVIIIa C2 domain form multiple points of contact with the Gla domain of fIXa at the nanodisc surface, including residues Y1-S3, E21-F25, and V46-D47 (Figure 5C). Lastly, our analysis suggests a novel interaction between residue K80 of the fIXa EGF-1 domain and an acidic patch at the A1/A3 domain interface of fVIIIa (Figure 5D-E) formed by residues E144, E1969-E1970, E1827-E1828, and E1987. Comparison of our fIXa model in the Xase:ND complex with the crystal structure of porcine fIXa (PDB ID: 1PFX) indicates the Gla and EGF-1 domains undergo a ∼60° swing relative to the EGF-2 and catalytic domains, positioning residue K80 to dock with the acidic patch at the fVIIIa A1/A3 domain interface (supplemental Figure 5).

Model of Xase complex reveals multiple intermolecular contacts between fVIIIa and fIXa. (A) Contacts between fVIIIa A2 domain (dark blue) and fIXa exosite II (light green). (B) Docking between fVIIIa A3 domain (cyan) and fIXa 99-loop (light green). (C) Contacts between fVIIIa C2 domain (cyan) and fIXa Gla domain (dark green). (D-E) Electrostatic surface potential (D) and cartoon representation (E) of fVIIIa (dark gray) and fIXa (light gray). Inset depicts contacts between fVIIIa acidic residues and fIXa residue K80.

Model of Xase complex reveals multiple intermolecular contacts between fVIIIa and fIXa. (A) Contacts between fVIIIa A2 domain (dark blue) and fIXa exosite II (light green). (B) Docking between fVIIIa A3 domain (cyan) and fIXa 99-loop (light green). (C) Contacts between fVIIIa C2 domain (cyan) and fIXa Gla domain (dark green). (D-E) Electrostatic surface potential (D) and cartoon representation (E) of fVIIIa (dark gray) and fIXa (light gray). Inset depicts contacts between fVIIIa acidic residues and fIXa residue K80.

Discussion

Understanding the domain organization and protein–protein interactions that mediate the assembly of the lipid-bound Xase complex is of great importance for treating clotting disorders. This study outlines the structural characterization of the ND-bound Xase complex, revealing the domain organization and intermolecular contacts between fVIIIa and fIXa. While techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) routinely provide higher resolution information than SAXS on macromolecular complexes in their native environments, SAXS sample preparation and data analysis are considerably less time-consuming and intensive. In addition to supporting previously suggested protein–protein contacts, our analysis provides evidence for a novel interaction between the fIXa EGF-1 domain and fVIIIa A1/A3 domain interface. Our model advances our understanding of how the Xase complex is formed and how mutations at the intermolecular interface may disrupt contacts between fVIIIa and fIXa.

Nanodiscs are a novel tool to study the intrinsic tenase complex

We calculated nanomolar affinities using His6-tagged nanodiscs for fVIIIa, fIXa, and the Xase complex (Table 1; Figure 1), supporting tagged nanodiscs as a convenient tool for studying lipid interactions with procoagulant proteins. Although these values are considerably higher than previously reported affinities for fVIIIa (2-5 nM), fIXa (12-1000 nM), and Xase (0.5 nM) using activated platelets and lipid vesicles,5,76-78 discrepancies may be due to the reduced surface area and size of nanodiscs and a limited number of available binding sites due to varying lipid composition. Lipid nanodiscs lacking phosphatidylserine demonstrated minimal affinity toward fVIIIa (supplemental Figure 6), supporting the critical role of phosphatidylserine in mediating procoagulant proteins binding to activated platelet surfaces. Indeed, activated platelets and lipid vesicles, prepared with 20% phosphatidylserine, present ∼600 to 1200 binding sites for fVIIIa and fIXa,78-80 yet inactive fIX had a reported KD of 390 nM with lipid nanodiscs,81 in good agreement with the KD reported in this study for fIXa. Lipid-binding procoagulant proteins utilizing a Gla domain such as fIXa present a wide range of reported affinities for lipid membranes, most likely due to the Ca2+-dependent conformational rearrangement to the Gla domain that facilitates membrane binding.

The apparent binding rates and affinity of the Xase complex (Table 1) are further complicated by binding and dissociation of free fVIIIa or fIXa and the phosphatidylserine lipid content, a limiting factor in binding clotting proteins to lipid membranes.5 Negative-staining electron microscopy on fVIII and nanodiscs composed of 80% phosphatidylserine suggested an increased formation of the lipid-bound complex.82 We attempted to optimize binding by increasing phosphatidylserine levels in the nanodisc; however, size exclusion chromatography of the assembled nanodiscs revealed a heterogeneous mixture with varying nanodisc sizes (data not shown). Nevertheless, all concentrations of Xase were at or above the reported KD for the fVIIIa/fIXa complex (4-5 nM) in similar conditions,83,84 suggesting that most binding events were contributed by the fully-formed Xase complex. We attempted to calculate binding affinities from a 2:1 binding model, as the nanodisc structure presents 2 potential binding sites on either side; however, the binding affinities were indeterminate. Furthermore, the SAXS-derived Rg and molecular envelope of the Xase:ND complex (Table 3; Figure 4) suggested only 1 Xase per nanodisc. This binding limitation may also be due to the empty nanodisc adopting a bent, elliptical conformation (Figure 3D), as previously suggested,45,69 , -73 that may promote optimal binding to one side over the other.

Previous experiments using nanodiscs82 and nanotubes85 have proposed fVIII adopts a homodimeric quaternary structure when bound to lipids. We attempted to model an fVIII homodimer using the electron crystallography-derived structure of lipid-bound fVIII (PDB ID: 3J2Q) to determine whether our data could support this model. Alignment between our experimental data and a theoretical SAXS scattering curve of dimeric fVIII bound to a nanodisc suggests poor agreement (supplemental Figure 7A), though this may be due to the presence of fIXa in our SAXS experiments which would theoretically disrupt potential fVIII dimerization.

Enzyme kinetic measurements further supported the necessary role of lipid nanodiscs in assembling the active Xase complex (Table 2). While our apparent Vmax is in good agreement with literature values (0.6-2.5 nM/min), our Km,app is higher than previously reported values (20-40 nM), indicating suboptimal substrate binding. This may be due to the incomplete alignment of interfacial contacts between the fVIIIa A2 domain and fIXa catalytic domain that are necessary for the formation of the Xase active site or partial activation of fVIII in the reaction vessel.86 Optimization of lipid nanodiscs properties, such as size and lipid content, may reorient Xase complex domains to promote substrate binding.

fVIIIa binds to fIXa via the A2, A3, and C2 domains

Several groups have provided a wealth of biochemical data on the intermolecular contacts between fVIIIa and fIXa, enhancing our understanding of how the Xase complex is formed and regulated.29-35 Calculating an ab initio molecular envelope of the Xase:ND complex allowed us to computationally dock fVIIIa to fIXa (Figure 4F) and investigate the feasibility of previously proposed protein–protein interactions as well as speculate on novel points of contact (Figure 5). Formation of the Xase complex is not predicted to alter the redox states of the disulfide bridges in fVIIIa or fIXa,87 limiting any conformational rearrangements to flexible linkers between domains.

First, fVIIIa residues 484-509 and 558-565 of the A2 domain and residues 1790-1798 and 1811-1818 of the A3 domain are predicted to bind to fIXa.38,88,89 Hydrogen-deuterium exchange protection patterns at exosite II and the 99-loop of fIXa have recently been identified in the presence of fVIIIa and are presumed to be binding sites for the cofactor.31,36 Our model suggests close proximity between the fVIIIa A2-A3 domains and fIXa catalytic domain and is in good agreement with the crystal structure of the homologous prothrombinase complex39 and fluorescence studies86 that suggest the Xase substrate binding site is positioned ∼70 Å above the phospholipid surface. This proposed domain organization provides a rationale for how binding to fVIIIa dramatically improves fIXa activity. Our Xase model places the 99-loop near an amphipathic cleft formed by fVIIIa residues 1790-1798 and 1803-1818 of the A3 domain (Figure 5B), leading us to speculate that the fIXa 99-loop binds to fVIIIa through a combination of hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions. Interestingly, a sequence alignment of fVIII residues 1700-1800 indicated porcine fVIII carries a glutamic acid at position 1797 while other species use a positively charged or neutral amino acid (supplemental Figure 8). Because the fVIII in this study is a chimera with porcine A1 and A3 domains, this extra acidic residue may strengthen interactions with the fIXa 99-loop, which could partially explain why porcine fVIII has enhanced activity in the presence of fIXa.90 The fIXa 99-loop is also positioned near a disordered loop on the fVIIIa A2 domain, comprised of residues 721-764, which may provide additional intermolecular contacts. Although dissociation of the A2 domain during SAXS data collection was a possibility, a model of the Xase:ND complex lacking the A2 domain did not improve the fit with the experimental data (supplemental Figure 7B). Furthermore, activated ET3i, constructed with porcine A1 and A3 domains, has previously been shown to have approximately threefold enhanced affinity for the A2 domain due to multiple stabilizing interactions at the A1/A2 and A2/A3 domain interfaces.44,63

Second, residues F25 and V46 of the fIXa Gla are predicted to bind to fVIIIa.32 Similarly, residues 2228-2240 of the fVIIIa C2 domain are a putative binding site for fIXa.33 Since the C1 and C2 domains of fVIIIa and the Gla domain of fIXa directly contribute to interactions with lipid membranes,5,7,12,32,91 we concluded that all 3 domains are docked onto the nanodisc surface with fVIIIa C2 domain and fIXa Gla domain in close proximity. A structure of the lipid-bound fVIII positioned the C2 domain partially embedded in the lipid membrane,92,93 a conformation that would prevent binding to the fIXa Gla domain.32,33 This C2 domain configuration remains to be supported using higher-resolution techniques such as X-ray crystallography, yet may present a novel mechanism for binding to fIXa.

Third, our docking studies between fVIIIa and fIXa suggest the fIXa Gla and EGF-1 domains undergo a 60° swing relative to the fIXa crystal structure (PDB ID: 1PFX), positioning the fIXa residue K80, located in the EGF-1 domain, near the fVIIIa A1/A3 domain interface (Figure 4D-E). This region of fIXa has previously been shown to bind to the fVIIIa light chain in a charge-dependent manner.94 Mass spectrometry studies on fVIIIa indicate a potential role for this region in regulating fVIIIa stability in the presence of fIXa. Alanine substitutions to residues K1967 and K1968, located adjacent to E1969 and E1970, revealed differential roles for each amino acid residue, with K1967A diminishing fVIIIa stability and K1968A enhancing fVIIIa stability.95 Binding residue K80 to fVIIIa may also stabilize the fIXa EGF-1/EGF-2 interface, which has been shown to modulate Xase assembly and activity.96 Docking the fIXa EGF-1 domain to the fVIIIa A1/A3 domain interface may be an additional protein–protein contact which stabilizes the overall Xase complex.

While the SAXS-derived model of the membrane-bound Xase complex presented here is in good agreement with previous biochemical data, the molecular envelope (Figure 4D) represents an average of all solution states97 and does not rule out alternative conformations. Indeed, unfilled space in Figure 4E can be attributed to dissociation of the fIXa Gla domain from the fVIIIa C2 domain, as previously suggested,40,41 or partial dissociation of the fVIIIa A2 domain.15,98 Multiple fluorescence studies indicate that fVIIIa binds to phospholipid membranes at a ∼50° angle relative to the phospholipid surface99,100 and binding to fIXa orients the catalytic domain ≥70 Å above the lipid surface.86 The low resolution of the SAXS data presented here precludes us from calculating a binding angle for the Xase complex, though alternate binding angles may have contributed to the averaged molecular envelope. Moreover, flexible loops within fVIIIa and fIXa increase the conformational sampling of the Xase complex. Computational modeling and low-resolution techniques have proposed novel fVIIIa conformations bound to lipid membranes,40,92,93 which may be mediated by the orientation of fVIIIa C1 domain.6 However, recent crystal structures of fVIII have revealed a flexible C2 domain that can adopt multiple conformations while the other fVIII domains are conformationally conserved.63,101,102 We attempted to account for alternative conformers of the Xase complex using MultiFOXS,67 a SAXS-based tool that allows for modeling multistate conformations of macromolecular complexes, but were unsuccessful due to incompatibility with the lipid nanodisc. Future work, such as X-ray crystallography or cryoEM, will provide insight into energetically favorable conformations of the Xase complex at a higher resolution.

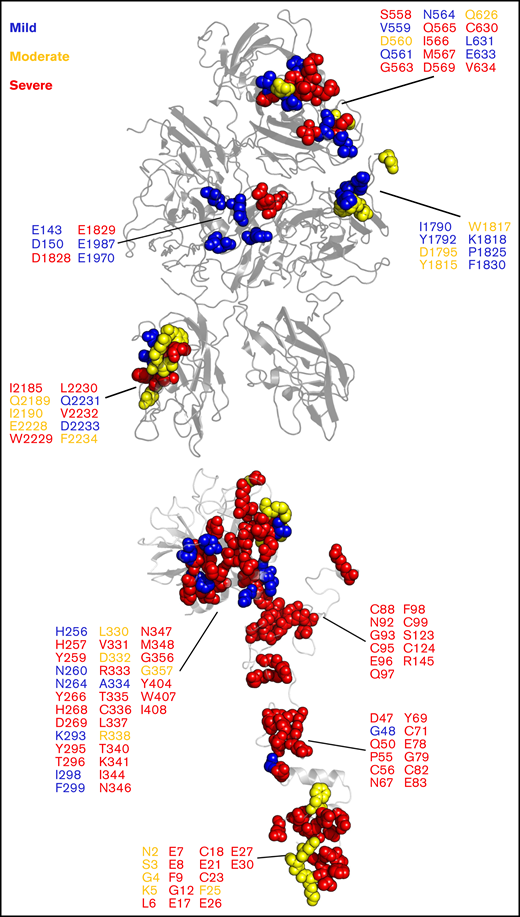

Mutations at the fVIIIa/fIXa interface are associated with clotting disorders

Our model of the Xase:ND complex provided remarkable insight into how mutations at the fVIIIa/fIXa interface may inhibit the formation of the complex. We analyzed the CHAMP/CHBMP hemophilia A and hemophilia B mutation databases, compiled by the Centers for Disease Control,103 and identified a series of mutations along the fVIIIa/fIXa interface that are associated with varying severities of hemophilia A or B (Figure 6). Intriguingly, mutations associated with mild to moderate hemophilia A are localized to the fVIII A1/A3 domain interface and the A3 domain near the putative binding site for the fIXa 99-loop. Severe hemophilia A mutations are localized to the A2 and C2 domains, specifically the 558-loop on the A2 domain, previously shown to be a strong determinant in binding to fIXa.30 We also identified several hemophilia B-related mutations in fIXa that may disrupt binding to fVIIIa, a majority of which are associated with severe cases. For instance, mutation of fIXa residue G79, located in the EGF-1 domain, to glutamic acid was identified in a hemophilia B patient with low fIXa coagulant activity.104 Substitution with a negatively charged amino acid would disrupt potential electrostatic contacts between fVIIIa and fIXa and reduce circulatory levels of Xase. Furthermore, residues 89-94 of the EGF-2 domain, previously shown to regulate the formation and activity of the Xase complex,75 may play a critical role in binding to fVIIIa. Mutations to residues N92 and G93 abolished fXa generation75,105 and are associated with severe hemophilia B (Figure 6). Our model of the Xase complex suggests these residues form direct contacts with the fVIIIa A2 domain, which may reduce the dissociation rate of the A2 domain and stabilize the active Xase complex.98

Hemophilia A- and hemophilia B-related mutations to fVIIIa/fIXa dimer interface. Mutations at the fVIIIa:fIXa interface were identified from the CHAMP and CHBMP database, as collated by the Centers for Disease Control, and depicted in sphere representation on the crystal structure of human fVIII (PDB ID: 6MF2, top) for hemophilia A and SWISS-MODEL of human fIXa generated from porcine fIXa (PDB ID: 1PFX, bottom, Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) numbering) for hemophilia B. Residues are colored by disease severity (blue: mild; yellow: moderate; red: severe).

Hemophilia A- and hemophilia B-related mutations to fVIIIa/fIXa dimer interface. Mutations at the fVIIIa:fIXa interface were identified from the CHAMP and CHBMP database, as collated by the Centers for Disease Control, and depicted in sphere representation on the crystal structure of human fVIII (PDB ID: 6MF2, top) for hemophilia A and SWISS-MODEL of human fIXa generated from porcine fIXa (PDB ID: 1PFX, bottom, Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) numbering) for hemophilia B. Residues are colored by disease severity (blue: mild; yellow: moderate; red: severe).

Conversely, our results also provide a mechanistic rationale for pathogenic variants on the fIXa 338-helix associated with deep vein thrombosis. Previous studies have characterized gain-of-function mutations to fIX residue R338, including the Padua mutant R338L and Shanghai mutant R338Q.22,23 Our modeling of the Xase complex suggests the A2 domain of fVIIIa contributes several acidic residues that may bind to and stabilize residue R338 (supplemental Figure 9), as previously proposed.31 Screening single-point mutations to residue R338 identified several amino acid substitutions, a majority of which were hydrophobic, that increase fIX activity, suggesting that R338 is evolutionarily conserved in order to suppress fIX activity.24 Hydrophobic substitutions to fIX residue R338, such as the Padua mutant, may be stabilized by fVIII residues I566 and M537. Interestingly, mutation of fVIII residues I566 or M567 to lysine or arginine is associated with moderate to severe hemophilia A,106-108 presumably due to charge–charge repulsion of the fIXa 338-helix. Incorporation of fIX variants V86A, located at the EGF-1/EGF-2 interface, and E277A, adjacent to the substrate-binding pocket109 with R338L, has been shown to synergistically enhance binding to fVIIIa ∼15-fold,110 further demonstrating allostery between the fIX heavy and light chains in regulating Xase complex assembly and activity. A triple variant of fIX containing R318Y, R338E, and T343Y outperformed the Padua mutant as a novel gene therapeutic in treating hemophilia B with no risk of thrombophilia.111 Residues R338 and T343 are located at the putative fVIIIa/fIXa interface and may form stabilizing contacts with the fVIIIa A2 domain. Together, these data suggest that binding between the fVIIIa A2 domain and fIXa helix-338 is a strong determinant in the formation and stabilization of the Xase complex and highlight several fIX residues to mutate in the design of next-generation hemophilia B gene therapeutics.112

In this study, we illustrate an updated paradigm on the membrane-bound Xase complex. Binding measurements between activated Xase proteins and immobilized nanodiscs measured nanomolar affinities. Solution scattering intensities of the Xase:ND complex allowed us to calculate biophysical parameters, such as Rg and Rc, and determine an ab initio molecular envelope of the protease complex. Our results support multiple domain–domain contacts involved in Xase complex assembly and emphasize the detrimental effects of fVIII and fIX point mutations in the pathogenesis of blood clotting disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted at the Advanced Light Source (ALS), a national user facility operated by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on behalf of the Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences, through the Integrated Diffraction Analysis Technologies (IDAT) program, supported by DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research. Additional support comes from the National Institutes of Health project ALS-ENABLE (P30 GM124169) and a High-End Instrumentation Grant S10OD018483. This work was supported by the Dreyfus Foundation (Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award) and the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (award numbers R15HL103518 and U54HL141981 to P.C.S., award numbers R44HL117511, R44HL110448, U54HL112309, and U54HL141981 to C.B.D., H.T.S., and P.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.C.C. planned experiments, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.C.P. planned experiments, performed experiments, and analyzed data; H.T.S., C.B.D., and P.L. developed expression and purification procedures for ET3i; C.B.D. and P.L. assisted in writing the manuscript; and P.C.S. planned experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.L. is the inventor on a patent application describing ET3i and is an inventor on patents owned by Emory University claiming compositions of matter that include modified fVIII proteins with reduced reactivity with anti-fVIII antibodies. C.B.D., P.L., and H.T.S. are cofounders of Expression Therapeutics and own equity in the company. Expression Therapeutics owns the intellectual property associated with ET3i. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Correspondence: P. Clint Spiegel, Department of Chemistry, Western Washington University, 516 High St, Bellingham, WA 98225, United States; e-mail: paul.spiegel@wwu.edu.

References

Author notes

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to P. Clint Spiegel (paul.spiegel@wwu.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.