Key Points

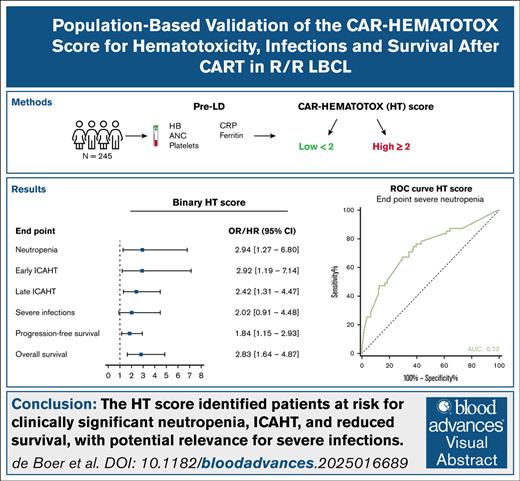

External validation confirmed the predictive value of the HT score for severe neutropenia, including early and late severe ICAHT.

The HT score identified patients at risk of reduced survival and harbors the potential to support risk stratification for severe infections.

Visual Abstract

Early identification of patients at risk of immune effector cell–associated hematotoxicity (ICAHT) is essential to minimize nonrelapse mortality. The CAR-HEMATOTOX (HT) score is an implemented risk-stratification tool for ICAHT, infections, and survival in patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL) receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CART). Although validated in its defining study, the HT score was developed in a small cohort, necessitating independent external validation. This study externally validates the HT score in a real-world population-based cohort of adults with R/R LBCL receiving CART. The HT score, based on absolute neutrophil count (ANC), hemoglobin, platelets, C-reactive protein, and ferritin, was calculated before lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Of 245 consecutive patients, 171 (70%) had an HT score of ≥2 (HThigh). The initial end point, clinically significant neutropenia (ANC of <500/μL for ≥14 days), occurred in 21% of patients. The binary HT score was associated with clinically significant neutropenia (odds ratio [OR], 2.94; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.27-6.80; P = .012) with a good predictive performance (area under the curve = 0.73). Similar results were achieved for early and late ICAHT grade ≥3 (OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 1.19-7.14; P = .019; and OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.31-4.47; P = .005). A trend toward an association with severe infections was observed (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 0.91-4.48; P = .085). HThigh patients had a lower progression-free and overall survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.15-2.93; P = .011; and HR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.64-4.87; P < .001, respectively). The HT score identified CART-treated patients with R/R LBCL at risk of clinically significant neutropenia, poor survival outcomes, and potentially severe infections.

Introduction

CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy (CART) has become an important pillar in the treatment of relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL), achieving durable responses in ∼40% to 50% of the patients.1,2 This personalized therapy, which relies on the anticancer cytotoxic effect of genetically engineered autologous T cells, is characterized by a distinct toxicity profile, resulting from CAR T-cell–related immune activation. The side effects cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) are well described, but recently awareness has been raised for the high incidence of severe hematotoxicity after CART.3-5

This immune effector cell–associated hematotoxicity (ICAHT) presents as severe (grade ≥3) thrombocytopenia in 28% to 65%, anemia in 16% to 77%, and neutropenia in 59% to 95% of patients.6-10 Several factors can contribute to the development of ICAHT, such as an impaired pre-CART hematopoietic bone marrow reserve caused by previous treatment lines or bridging therapy, a state of systemic and local bone marrow inflammation either preexistent or caused by secretion of CART-related cytokines, and immune alterations owing to imbalances in T-cell–B-cell homeostasis.6,10,11

Profound ICAHT can result in increased transfusion needs over time and severe infectious complications, the latter known to drive nonrelapse mortality (NRM) after CART.12-14 Therefore, the European Hematology Association (EHA) and the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EMBT) endorsed an ICAHT classification system based on the duration and depth of neutropenia, creating opportunities for preventive management strategies and to foster homogeneity in the reporting of ICAHT.5

Given that early identification of patients at risk is crucial, the CAR-HEMATOTOX (HT) score was developed as a preinfusion risk-stratification tool for severe neutropenia, infections, and survival outcomes in patients with R/R LBCL treated with CART.9,15 This easy-to-use score is determined before lymphodepleting chemotherapy based on hematopoietic reserve (absolute neutrophil count [ANC], hemoglobin [Hb], and platelet count) and state of inflammation (C-reactive protein [CRP] and ferritin). Currently, the HT score is widely implemented, recommended by the EHA/EBMT, and extended to different disease entities and CAR T-cell products.5,16,17

Although the HT score was validated for patients with R/R LBCL in its defining study, it was developed in a rather small cohort (n = 55), with a low positive predictive value.9 Given that no fully independent, multicenter validation has been performed for infections and survival next to the original end point of hematotoxicity, a comprehensive external validation is warranted to evaluate the broad clinical utility of the HT score. In this study, we examine the predictive performance of the HT score for clinically significant neutropenia, including early and late ICAHT grade ≥3, severe infections, and poor survival outcomes in an independent, population-based, real-world LBCL CART cohort of 245 patients.

Methods

Patient population and data collection

In this multicenter retrospective cohort study, all patients with R/R LBCL after ≥2 lines of immunochemotherapy treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel between May 2020 and December 2023 across all 7 adult CART centers in the Netherlands were included, with a data cutoff date of 1 March 2024. Eligibility for CART was approved by the Dutch CAR-T Tumorboard according to the criteria previously described.18 Patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine according to manufacturers’ protocol, followed by a single infusion of CAR T-cells. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient data and laboratory values were extracted from medical records and collected in the national Follow-that-CAR database after institutional review board approval (NL76835.018.21).

HT score

The HT score was calculated per original report, with 1 point allocated for the following parameters: platelet count of 75 × 109/L to 175 × 109/L, ANC of <1200/μL, Hb of <9.0 g/dL, CRP of >3.0 mg/dL, and ferritin of 650 to 2000 ng/mL. Two points were assigned for a platelet count of <75 × 109/L and ferritin of >2000 ng/mL. These laboratory parameters were preferably determined on the day of lymphodepleting chemotherapy (day −5), but at least between days −9 and −3. Patients with at least 3 of 5 laboratory parameters were included. HThigh patients were defined as patients with an HT score of ≥2, whereas HTlow patients had an HT score of <2.

Hematologic toxicity grading and end points

Based on original reports, severe neutropenia was defined as ANC of <500/μL, profound neutropenia as ANC of <100/μL, and protracted neutropenia as duration of ≥7 days. Clinical phenotypes of neutrophil recovery were determined using the following definitions: (1) quick recovery, sustained recovery without a second dip of ANC of <1000/μL; (2) intermittent recovery, recovery with ANC of >1500/μL followed by a second dip of ANC of <1000/μL after day 21; or (3) aplastic, ANC of <500/μL for ≥14 days.9

The primary end point of this study was clinically significant neutropenia, defined as ANC of <500 cells per μL for >14 days between days 0 and 60 after CAR T-cell infusion.9 Secondary end points were severe early and late ICAHT (grade ≥3), automatically calculated as previously described5,12,19; severe infections (grade ≥3) in the first 3 months after CAR T-cell infusion (days 0-90); progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from CAR T-cell infusion to progression or death from any cause or last follow-up, whichever occurred first; overall survival (OS), defined as the time from CAR T-cell infusion to death from any cause or last follow-up, whichever occurred first, and NRM, defined as death after CART without previous relapse or disease progression.20 For OS, censoring was performed in patients still alive at the last known follow-up date and, in addition for PFS, performed for the death of any other cause than progressive disease (PD). Infection severity was classified on a 5-grade scale from mild, moderate, severe, life-threatening, or fatal, as previously reported.15,21 Neutropenic fever without clinical signs of infection and/or microbiologic evidence was not considered as an infectious event.

Statistical analyses

To evaluate the performance of the HT score, missing values were imputed with multiple imputation by chained equation using predictive mean matching for 10 data sets (supplemental Methods 1). Pooled results were reported using Rubin’s rules.22,23 Descriptive statistics of variables were provided. Differences between groups were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test for absolute values and the Fisher exact test for proportions. Univariable analyses were performed using linear regression for continuous variables, logistic regression for binary variables, and Cox regression for survival end points. Receiver operating characteristic curves with the respective area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and hazard and odds ratios (ORs) (including the 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were reported. Optimal cutoff points for each HT laboratory parameter and the HT score itself to predict clinically significant neutropenia were identified by maximizing the Youden J statistic (sensitivity + specificity – 1). Correlations between continuous variables were analyzed with the Spearman correlation coefficient (r). Kaplan-Meier curves were created to assess PFS and OS, and cumulative incidence curves to assess NRM. P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.3.3. We used the TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis) checklist for reporting of results, when applicable (supplemental Methods 2).24

Results

Trial population

In total, 250 consecutive patients treated with CD19-directed CART as standard of care between May 2020 and December 2023 in the Netherlands were included. Of these, 4 patients were excluded because <3 laboratory parameters of the HT score were available before lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Of 1 patient, no follow-up data were available. Data on the laboratory markers were complete for 142 patients. Four of 5 laboratory markers were available in 85 patients, and 3 of 5 laboratory markers in 19 patients. Imputation of clinical variables was performed for ferritin (35%), CRP (7%), platelets (6%), neutrophils (2%), and neutropenia (1%) in the included 245 patients.

The median age was 62 years, ranging from 20 to 84 years (Table 1). Most patients were diagnosed as having diffuse LBCL (n = 131; 53%), whereas 76 patients had transformed follicular lymphoma (31%). Stage III to IV disease was present in 193 patients (79%). As expected, this patient population was heavily pretreated before the start of lymphodepleting chemotherapy, resulting in a median number of previous therapy lines of 2 (range, 2-6), of whom 66 patients (27%) received an autologous stem cell transplantation and 3 patients (1%) both an autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. In addition, bridging therapy was administered in 192 patients before the CAR T-cell infusion (78%), comprising radiotherapy (n = 70; 29%), systemic therapy (n = 57; 23%), steroids (n = 20; 8%), or a combination of these therapies (n = 45; 18%). The median HT score was 2 (interquartile range [IQR], 1-3) (supplemental Figure 1). A substantial part of the patients (n = 171; 70%) had an HT score of ≥2 (HThigh), whereas 74 patients (30%) had an HT score of <2 (HTlow). HThigh patients more often had stage III to IV disease than HTlow patients (83% vs 70%; P = .041). Except for the laboratory parameters included in the score, other baseline characteristics were not different between HThigh and HTlow patients (supplemental Table 1).

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics . | Total (N = 245) . |

|---|---|

| Age,∗ median (range) | 62 (20-84) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 160 (65.3) |

| Diagnosis,∗ n (%) | |

| DLBCL | 131 (53) |

| tFL | 76 (31) |

| HGBCL DH/TH | 23 (9.4) |

| HGBCL NOS | 8 (3.3) |

| T-cell–rich LBCL | 2 (0.8) |

| PMBCL | 5 (2.0) |

| Stage III-IV,∗ n (%) | 193 (79) |

| CNS involvement,∗ n (%) | 12 (5) |

| No. of previous therapy lines,∗ median (range) | 2 (2-6) |

| Previous SCT, n (%) | 69 (28) |

| Autologous SCT | 66 (27) |

| Autologous and allogeneic SCT | 3 (1) |

| CRP,† median (IQR), mg/dL | 1.11 (0.30-3.20) |

| Ferritin,† median (IQR), ng/mL | 638 (322-1204) |

| Neutrophils,† median (IQR), per μL | 3240 (2050-4510) |

| Platelets,† median (IQR), g/L | 179 (121-229) |

| Hb,† median (IQR), g/dL | 11.3 (9.7-12.6) |

| Characteristics . | Total (N = 245) . |

|---|---|

| Age,∗ median (range) | 62 (20-84) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 160 (65.3) |

| Diagnosis,∗ n (%) | |

| DLBCL | 131 (53) |

| tFL | 76 (31) |

| HGBCL DH/TH | 23 (9.4) |

| HGBCL NOS | 8 (3.3) |

| T-cell–rich LBCL | 2 (0.8) |

| PMBCL | 5 (2.0) |

| Stage III-IV,∗ n (%) | 193 (79) |

| CNS involvement,∗ n (%) | 12 (5) |

| No. of previous therapy lines,∗ median (range) | 2 (2-6) |

| Previous SCT, n (%) | 69 (28) |

| Autologous SCT | 66 (27) |

| Autologous and allogeneic SCT | 3 (1) |

| CRP,† median (IQR), mg/dL | 1.11 (0.30-3.20) |

| Ferritin,† median (IQR), ng/mL | 638 (322-1204) |

| Neutrophils,† median (IQR), per μL | 3240 (2050-4510) |

| Platelets,† median (IQR), g/L | 179 (121-229) |

| Hb,† median (IQR), g/dL | 11.3 (9.7-12.6) |

CNS, central nervous system; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HGBCL DH/TH, high-grade B-cell lymphoma double hit/triple hit; HGBCL NOS, high-grade B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified; SCT, stem cell transplantation; tFL, transformed follicular lymphoma.

At screening.

Before lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Neutropenia

Severe neutropenia (ANC of <500/μL) after CART was present in 228 patients (93%). Among these, 104 patients (42%) developed profound neutropenia (ANC of <100/μL). The resolution of severe neutropenia required 7 or more days in 140 patients (57%), whereas profound neutropenia persisted for at least 7 days in 12 patients (5%). Clinically significant neutropenia (ANC of <500/μL for ≥14 days) was observed in 55 patients (22%). Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was administered in 117 patients (48%) after a median of 37 days (IQR, 28-68) from CAR T-cell infusion and was continued for a median of 48 days (IQR, 20-111).

The 3 predefined neutrophil recovery phenotypes were identifiable within this cohort (Figure 1A). All phenotypes exhibited an initial period of neutropenia after lymphodepleting chemotherapy and CAR T-cell infusion. A quick recovery phenotype was observed in 134 patients (55%), an intermittent recovery phenotype in 56 patients (23%), and an aplastic phenotype in 55 patients (22%). Patients in the HThigh group were more likely to exhibit an aplastic neutrophil recovery phenotype than those in the HTlow group (27% vs 11%) (Figure 1B). In addition, the median duration of severe neutropenia was significantly longer in the HThigh group (8 days [95% CI, 0-46] vs 6 days [95% CI, 0-28] in the HTlow group; P = .001) (Figure 1E-F). In addition, a trend toward a more frequent administration of G-CSF was observed in HThigh patients than in HTlow patients (51% vs 39%; P = .095) (Figure 1C).

The HT score stratifies patients with severe neutropenia after CART. (A) Aggregate ANC over time (day −6 until 120) per neutrophil recovery phenotype: quick recovery (n = 134 [55%]), intermittent recovery (n = 56 [23%]), and aplastic (n = 55 [22%]). (B) Relative incidences of neutrophil recovery phenotypes (quick recovery, intermittent recovery, and aplastic), split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (C) Percentages of patients receiving G-CSF after CAR T-cell infusion, split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (D) Relative incidences of early and late ICAHT severity, split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (E) Aggregate ANC over time (day −6 until 120), split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (F) Total duration of neutropenia between days 0 and 60 divided by a low vs high HT score. (G) ROC curve of the continuous HT score for the end point clinically significant neutropenia (ANC of ≤500/uL for ≥14 days). ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

The HT score stratifies patients with severe neutropenia after CART. (A) Aggregate ANC over time (day −6 until 120) per neutrophil recovery phenotype: quick recovery (n = 134 [55%]), intermittent recovery (n = 56 [23%]), and aplastic (n = 55 [22%]). (B) Relative incidences of neutrophil recovery phenotypes (quick recovery, intermittent recovery, and aplastic), split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (C) Percentages of patients receiving G-CSF after CAR T-cell infusion, split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (D) Relative incidences of early and late ICAHT severity, split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (E) Aggregate ANC over time (day −6 until 120), split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (F) Total duration of neutropenia between days 0 and 60 divided by a low vs high HT score. (G) ROC curve of the continuous HT score for the end point clinically significant neutropenia (ANC of ≤500/uL for ≥14 days). ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

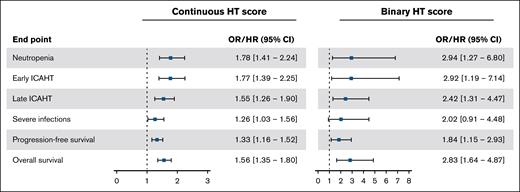

Both the binary and continuous HT scores were significantly associated with clinically significant neutropenia (Figure 2). The OR for the continuous HT score was 1.78 (95% CI, 1.41-2.24; P < .001), and for the binary HT score was 2.94 (95% CI, 1.27-6.80; P = .012). The continuous HT score showed a good predictive performance with an AUC of 0.73 (Figure 1G). Using the cutoff of 2 (binary HT score), the sensitivity was 84% and the specificity was 36%. As a sensitivity analysis, similar (performance) results were achieved when the association of the HT score with clinically significant neutropenia was evaluated using data with complete cases only, namely an AUC of 0.73, sensitivity of 79%, and specificity of 41% (n = 142) (supplemental Table 2).

Association of the continuous and binary HT scores with clinically significant neutropenia, early ICAHT, late ICAHT, severe infections, PFS, and OS. Continuous HT score ranged from 1 to 7. Binary HT score is presented using a cutoff of ≥2. ORs/HRs are presented with squares and 95% CI with whiskers. HR, hazard ratio.

Association of the continuous and binary HT scores with clinically significant neutropenia, early ICAHT, late ICAHT, severe infections, PFS, and OS. Continuous HT score ranged from 1 to 7. Binary HT score is presented using a cutoff of ≥2. ORs/HRs are presented with squares and 95% CI with whiskers. HR, hazard ratio.

Among the individual laboratory components included in the HT score, Hb, platelet count, CRP, and ferritin were each univariably associated with clinically significant neutropenia when analyzed as continuous variables (supplemental Table 4) (ORs, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66-0.92; P = .003), at 0.57 (95% CI, 0.38-0.85; P = .006), 1.07 (95% CI, 1.01-1.14; P = .015), and 1.07 (95% CI, 1.03-1.10; P < .001), respectively. The same 4 parameters were associated with the duration of neutropenia (supplemental Figure 2). When using the cutoff of the laboratory parameters within the HT score, all laboratory parameters were associated with clinically significant neutropenia (supplemental Table 4).

In addition, we evaluated the incidence of early and late ICAHT using the EHA/EBMT grading system. Early ICAHT grade ≥3 was present in 49 patients (20%) and occurred more often in patients with a high HT score than in patients with a low HT score (25% vs 9%) (Figure 1D). Besides a higher incidence of late ICAHT grade ≥3 in our cohort (n = 112 [46%]), a similar trend was observed in the distribution of late ICAHT grade ≥3 between the HThigh and HTlow groups (52% vs 29%) (Figure 1D). These differences translated a significant association of both the continuous and binary HT scores with early ICAHT grade ≥3 (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.39-2.25; P < .001; and OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 1.19-7.14; P = .019) and late ICAHT grade ≥3 (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.26-1.90; P < .001; and OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.31-4.47; P = .005) (Figure 2; supplemental Table 2).

To investigate the generalizability of the cutoff for the HT score (≥2) and its individual laboratory components, we followed the same approach as Rejeski et al9 and determined the optimal cutoffs to distinguish high- and low-risk patients (supplemental Table 4). Based on the original HT score definition, this resulted in a new optimal HT score cutoff of ≥3, where 105 patients (43%) were classified as HTlow and 140 patients (57%) as HThigh. Using this new cutoff, the OR was 4.38 (95% CI, 2.05-9.39; P < .001), and the sensitivity and specificity were 70% and 66%, respectively (supplemental Table 4). Most of the newly found optimal cutoffs for the individual laboratory parameters differed minimally compared with the cutoffs previously found (supplemental Table 4).

Infections

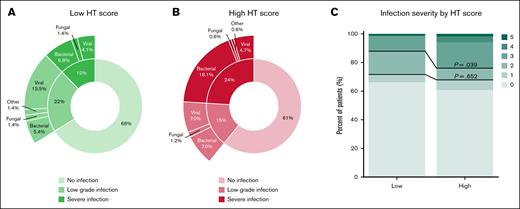

A total of 92 patients (37%) developed an infectious complication within the first 3 months after infusion. Severe infections were the most common, accounting for 42% of all infectious complications. Life-threatening infections occurred in 3% of the cases (n = 7), whereas fatal infections were observed in 2% of patients (n = 4). Patients with severe infections more often received G-CSF than patients without severe infections (65% vs 43%; P = .005) (supplemental Figure 3). Infections graded as severe or higher were primarily of bacterial origin (n = 36; 72%), followed by viral infections (n = 11; 22%). Fungal infections were present in only 2 patients (4%), and 1 patient exhibited an infection of unknown origin (2%) (Figure 3A-B). Most of the severe infections originated from the bloodstream (n = 15; 30%), followed by the lower respiratory tract (n = 10; 20%) and line infections (n = 7; 14%) (supplemental Table 6).

Distribution of infection grades by HT score. (A) Distribution of infection grades and infection type in patients with a low HT score. (B) Distribution of infection grades and infection type in patients with a high HT score. (C) Infection severity according to a low and high HT score. Low-grade infection represents infection grades 1 to 2. Severe infection is defined as an infection grade ≥3. Upper P value describes the difference between HThigh and HTlow patients in the incidence of infection grade ≥3, and lower P value in the incidence of infection grade ≥2.

Distribution of infection grades by HT score. (A) Distribution of infection grades and infection type in patients with a low HT score. (B) Distribution of infection grades and infection type in patients with a high HT score. (C) Infection severity according to a low and high HT score. Low-grade infection represents infection grades 1 to 2. Severe infection is defined as an infection grade ≥3. Upper P value describes the difference between HThigh and HTlow patients in the incidence of infection grade ≥3, and lower P value in the incidence of infection grade ≥2.

Among the patients who developed any infection, 27% had a high HT score before the start of treatment. For those with severe infections, 18% had a high HT score. Patients with a high HT score were more likely to experience severe infections than those with a low HT score (24% vs 12%; P = .039; OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 0.91-4.48; P = .085) (Figure 3A-C). When considering the continuous HT score, there was a significant association with infections graded as severe or higher with an OR of 1.26 (95% CI, 1.03-1.56; P = .027) (Figure 2; supplemental Table 5). No substantial differences were noted in the association between the HT score and severe infections when analyzing only the complete cases (supplemental Table 3). Clinically significant neutropenia was not statistically associated with severe infections (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 0.81-3.31; P = .17). Next, given that neutropenia and therefore the HT score have a weaker association with viral infections, these were excluded from the analysis to investigate whether the HT score as proposed has potential to guide antibiotic prophylaxis strategies in this cohort.15 Excluding severe viral infections yielded a similar association between the continuous score and severe nonviral infections, as was observed for overall severe infections (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.05-1.66; P = .018; vs OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.03-1.56; P = .027) (supplemental Table 7). A comparable pattern was observed for the binary HT score (OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 0.94-6.43; P = .067; vs OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 0.91-4.48; P = .085) (supplemental Table 7).

No association between CRS grade ≥2 and severe infections was observed (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.58-2.01; P = .82), whereas a trend toward an association was observed for ICANS grade ≥2 (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 0.99-3.47; P = .06). Any tocilizumab or steroid administration did not increase the probability of severe infections, whereas the number of tocilizumab administrations was associated with severe infections (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.10-1.72; P = .005) (supplemental Table 8). Data on the cumulative dose of steroids were not available.

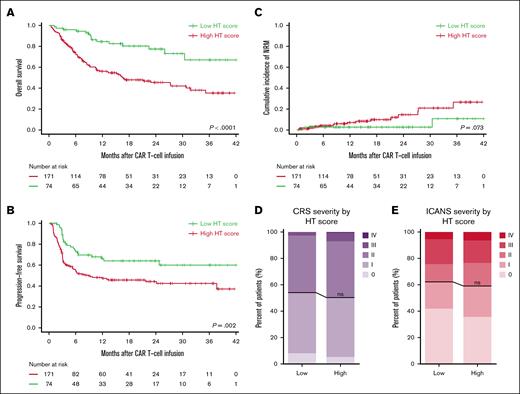

Survival

With a median follow-up of 12 months, the overall response rate was 85%, with 68% of patients achieving complete response, 17% partial response, 3% stable disease, and 13% PD as best response. Furthermore, HThigh patients exhibited worse PFS and OS than HTlow patients (P = .002 and P < .001, respectively) (Figure 4A-B), where the hazard ratio for PFS was 1.84 (95% CI, 1.15-2.93; P = .11) and for OS 2.83 (95% CI, 1.64-4.87; P < .001) (Figure 2). We obtained similar results for the association between the HT score and survival outcomes when analyzing only complete cases (supplemental Table 3). Although mortality rates were higher in patients with a high HT score, no substantial differences between HTlow and HThigh patients were noted in the most common causes of death, namely PD or relapse (71% vs 69%) or infection (14% vs 15%) (supplemental Table 9).

Discriminatory capacity of the HT score for OS, PFS, NRM, and the CAR T-cell–related toxicities CRS and ICANS. (A) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS by the HT score. (B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS by the HT score. (C) Cumulative incidence of NRM by the HT score. (D) Relative distribution of CRS severity by HT score. (E) Relative distribution of ICANS severity by HT score. The black line describes the difference between HThigh and HTlow patients.

Discriminatory capacity of the HT score for OS, PFS, NRM, and the CAR T-cell–related toxicities CRS and ICANS. (A) Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS by the HT score. (B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS by the HT score. (C) Cumulative incidence of NRM by the HT score. (D) Relative distribution of CRS severity by HT score. (E) Relative distribution of ICANS severity by HT score. The black line describes the difference between HThigh and HTlow patients.

The most common causes of NRM were infectious complications (n = 13). More rare causes of NRM were caused by CAR T-cell treatment–related toxicities (n = 2), myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 1), and retroperitoneal bleeding (n = 1). For 2 patients, the cause of NRM was unknown. A trend toward a higher cumulative incidence rate of NRM was seen in patients with a high HT score than those with a low HT score (P = .073) (Figure 4C). Regarding treatment-related toxicity, 199 patients (49%) developed a CRS grade ≥2 and 98 (40%) ICANS grade ≥2. No differences between the incidence of CRS or ICANS grade ≥2 were found for HTlow and HThigh patients (Figure 4D-E).

Discussion

In this national population-based study, an independent external validation of the HT score was performed for the original end points of clinically significant neutropenia, severe infections, and survival outcomes in 245 patients with R/R LBCL treated with CART. In addition, we evaluated the performance of the HT score for early and late ICAHT grade ≥3. A high HT score before lymphodepleting chemotherapy stratified patients with clinically significant neutropenia with a good predictive performance and was significantly associated with early and late ICAHT grade ≥3. Patients with a high HT score exhibited a reduced PFS and OS after CAR T-cell infusion compared with patients with a low HT score. The HT score had potential in stratifying patients with an increased risk of severe infections.

A prospective validation of the HT score and a simplified version already confirmed the predictive performance of the score for survival outcomes in patients with R/R LBCL, but no comprehensive validation of the HT score was performed, given that data on the original end point for neutropenia and infections were not reported.25 This study confirms, in a population-based cohort, the potential of the HT score to predict patients at risk of clinically significant neutropenia with a good predictive performance. Although we observed a lower sensitivity and specificity with a cutoff of 2 than initially reported (84% and 36% vs 95% and 67%, respectively), our findings emphasizes the potential of the HT score as a screening tool with an inclusive nature preventing undertreatment when guiding management strategies to reduce duration and depth of neutropenia and severe infections.9 Moreover, the validation of the HT score as a tool to identify patients with reduced PFS and OS provides the opportunity to selectively improve CART outcomes in this group of patients.15

Compared with the initially described study population, we observed a comparable incidence of severe neutropenia from days 0 to 90 after CAR T-cell infusion. However, the course was more often less profound and protracted, resulting in a relatively higher abundance of patients with a quick recovery phenotype and therefore less and later G-CSF administration. Although the percentage of patients with an aplastic phenotype was similar, the incidence of the primary end point of clinically significant neutropenia was lower than in the previously reported European cohorts (22% vs 40% [training cohort] and 41% [validation cohort]).9 This might result from an earlier administration of CART (median previous lines of therapy 2 vs 3), more frequent use of local radiotherapy as a bridging strategy instead of chemoimmunotherapy in this cohort, and/or improved toxicity management strategies, reducing local inflammation shortly after CAR T-cell infusion and therefore the duration of neutropenia. Early ICAHT grade ≥3 closely aligns with the definition of clinically significant neutropenia, and its incidence in a later reported multicenter observational study of 334 patients with LBCL was comparable with that observed in our cohort (23% vs 20%), underscoring the evolving paradigm in clinical practice and toxicity management.12

In our cohort, the HT score had a lower discriminatory ability for severe infections, given that only 24% of the patients with a high HT score developed a severe infection (≥grade 3) compared with the reported 40% and the incidence of any infection was similar between HTlow and HThigh patients (34% and 39%).15 The incidence rate of infectious complications, including severe infections, was slightly lower than previously reported, most likely owing to improved management strategies over time.15 Although the exclusion of viral infections may have further reduced the statistical power owing to lower event rates, the results remained comparable with those observed for all severe infections, supporting the association between the HT score and severe nonviral infections. Besides the potential reduced power, prioritizing different risk factors in the onset of severe infections might play a role. Of all components of the HT score, only Hb and CRP were significantly associated with the severe infections, suggesting that a reduced bone marrow reserve and increased inflammation or tumor burden before lymphodepleting chemotherapy might influence the occurrence of severe infections in this cohort. Although in this study only the number of tocilizumab administrations was associated with severe infections, other factors, such as a higher amount of previous lines of therapy including bridging therapy, the occurrence and severity of CRS and ICANS, and administration of tocilizumab and/or steroids, have been described to increase the risk of severe infections.21,26 This multifactorial approach is currently not fully covered within the HT score and therefore might explain the lower discriminatory capacity for severe infections.

Although initial concerns about overfitting of the model had been raised by Rejeski et al,9 the cutoffs of the laboratory parameters within the HT score determined for the neutropenia end point proved to be generalizable, given that the newly determined optimal cutoffs in our cohort stayed within a clinical range of the original cutoffs. We observed maximization of the Youden index when using the cutoff of ≥3 instead of ≥2, because a more equal distribution of HTlow and HThigh patients resulted in a more balanced sensitivity and specificity for clinically significant neutropenia (70% and 66% vs 84% and 36%, respectively). However, we agree with the initial chosen cutoff of 2, given that a higher sensitivity and a negative predictive value are preferable for the clinical application of the HT score in reducing severe neutropenia and infections aimed at preventing undertreatment.

This population-based study included only patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel, given that tisagenlecleucel was not available in all centers within the chosen timeframe. Consequently, the obtained results represent the behavior of a CD28-CAR, which is likely to induce more severe hematotoxicity, and therefore, these results cannot be fully extrapolated toward a 41BB-CAR.5,27 Another limitation is that the use of G-CSF might have influenced our primary end point and the relationship between severe neutropenia and infections, especially because it was prescribed at physicians’ discretion. Furthermore, we were unable to perform a fully comprehensive validation of the HT score’s predictive performance.28 Given that we did not have access to the original multivariable model containing the individual laboratory variables separately, we lacked the necessary coefficients to replicate and assess the model’s calibration and discrimination in full detail. Consequently, our validation was restricted to evaluating the HT score as a composite measure, rather than assessing the independent contributions of each variable within a multivariable framework.

In the current EHA/EBMT consensus grading and best practice guidelines for ICAHT, the HT score, at that time pending independent prospective validation, was implemented as a risk-stratification tool with the advice to consider bone marrow evaluation and earlier post-CART (day +2) administration of G-CSF in HThigh patients.5,12 This population-based study supports these advices, although some caution is needed for the end point severe infections, given that a lower incidence and lower discriminatory capacity of the HT score for severe infections were observed compared with previously reported. It would be of interest to assess the predictive performance of the HT score determined at baseline rather than before lymphodepleting chemotherapy, given that this could extend the timeframe for implementing preventive measures and potentially inform the selection of an appropriate bridging strategy.

In conclusion, higher HT scores identified patients at risk of severe neutropenia, including early and late ICAHT grade ≥3, reduced survival outcomes, and demonstrated potential to support risk stratification for severe infections after CART in this population-based, real-world LBCL cohort.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and their informal caregivers and the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment teams, with special attention to the clinical trial offices, the Dutch CAR-T Tumorboard, and all the referring centers.

Authorship

Contribution: J.W.d.B., K.K., A.G.H.N., and T.v.M. conceptualized and designed the study; J.W.d.B., S.v.D., P.G.N.J.M., J.A.v.D., Y.I.M.S., L.W.M., A.E.P., E.J.K., A.S-S., J.O., A.M.P.D., W.B.C.S., M.T.K., E.R.A.P., A.M.S., M.J.K., M.J., M.W.M.v.P., and J.S.P.V. collected and assembled data; K.K. and J.W.d.B. analyzed and interpreted the data; L.V.v.D., A.G.H.N., and T.v.M. supervised data analysis and interpretation; and all authors participated in the drafting, review, and approval of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.W.d.B. is supported by a partnership of University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) UMCG-Siemens for building the future of health (PUSH 2020) unrelated to this project. A.G.H.N. discloses conflicts of interest all outside of the submitted work with Siemens and Genentech. M.T.K. has a consulting/advisory role for CellPoint. M.J. received honoraria from Kite/Gilead and Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS)/Celgene, has a consulting/advisory role for Janssen, and received research funding from Novartis. M.W.M.v.d.P. received honoraria from Kite/Gilead and Takeda. M.J.K. received honoraria from and performed in a consulting/advisory role for BMS/Celgene, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, Novartis, and Roche; received research funding from Kite/Gilead, Roche, Takeda, and Celgene; and travel support from Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, Novartis, and Roche (all to institutions). L.V.v.D. received funding and salary support unrelated to this project from Dutch Research Council (NWO) Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) via the Veni (NWO-09150162010173) individual career development grant and Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) Young Investigator Grant (KWF-13529). T.v.M. has served on the advisory boards of Kite/Gilead, Celgene/BMS, Jansen, and Lilly; and received research funding from Kite/Gilead, Celgene/BMS, Genentech, and Siemens. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the Dutch CAR-T Tumorboard appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Tom van Meerten, Department of Hematology, University Medical Center Groningen, Hanzeplein 1, 9713GZ Groningen, The Netherlands; email: t.van.meerten@umcg.nl.

References

Author notes

Requests for the original data, restricted to nonidentifying data owing to privacy concerns, can be directed to the corresponding author, Tom van Meerten (t.van.meerten@umcg.nl).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![The HT score stratifies patients with severe neutropenia after CART. (A) Aggregate ANC over time (day −6 until 120) per neutrophil recovery phenotype: quick recovery (n = 134 [55%]), intermittent recovery (n = 56 [23%]), and aplastic (n = 55 [22%]). (B) Relative incidences of neutrophil recovery phenotypes (quick recovery, intermittent recovery, and aplastic), split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (C) Percentages of patients receiving G-CSF after CAR T-cell infusion, split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (D) Relative incidences of early and late ICAHT severity, split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (E) Aggregate ANC over time (day −6 until 120), split for HTlow and HThigh patients. (F) Total duration of neutropenia between days 0 and 60 divided by a low vs high HT score. (G) ROC curve of the continuous HT score for the end point clinically significant neutropenia (ANC of ≤500/uL for ≥14 days). ROC, receiver operating characteristic.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/21/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016689/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016689-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1766128676&Signature=4lJfEG6Ma5Tp7Bnk5tzoRb3IenhVmpReHT~8jie5xuSDSJxgJx7mWuk07s9aQx10HeSKo21-VAjz1BqdYz6BB5suMqNQGwd5IbrPyG4H9Ke9DQJYbkNCEiPdV54dw~qq2L5B4lsZeGPeouJ5s6M6mYt6MsUy3o3el1Phj4uPx2~MkI-Iv1tO3~DtdWoYv8Nzx4mIV8K8xzAROHTrsmSNVH2otCoSKAuabnGqQEm9ibpNnRjfkz4GqJlAAnVJB5H6vxl3kVHKIRHWHRT4f4QPTZgt748ZjhkpyFWX9bGtp22J2DvfJaVP57U-ZXcj0bM6jsB9BM27dMoP~UdDi3FBrQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)