Adoptive transfer of virus-specific T cells (VSTs) has been used for managing viral diseases in immunocompromised patients, including those undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and solid organ transplantation. Clinical trials targeting viruses such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, adenovirus, and BK virus have demonstrated effective viral control without the toxicities associated with conventional antiviral therapies. This review explores the manufacturing, feasibility, safety, and efficacy of VSTs, complemented by 2 case studies illustrating their real-world application. We examine recent advancements in VST manufacturing that broaden their accessibility and applicability to a wider range of viral infections and immunocompromised populations. Key safety considerations, including cytokine release syndrome and graft-versus-host disease, are discussed. Lastly, we assess the expanding applications of VSTs against emerging viral targets, such as COVID-19, and address current barriers to their implementation beyond the research setting.

Introduction

T-cell immunity is integral to the control of many viral infections. Absence or suppression of T cells results in susceptibility to prolonged or severe viral infections in a variety of clinical contexts, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT), inborn errors of immunity (IEIs), and solid organ transplantation (SOT). Despite advancements in antiviral pharmacotherapy, persistent and recurrent viral infections continue to drive morbidity and mortality in these vulnerable populations.1,2 Over the past 30 years, adoptive virus-specific T cell (VST) therapy has emerged as a promising antiviral strategy for severe and refractory viral infections in immunocompromised patients. Data supporting VST safety and efficacy continue to expand, though gold-standard, blinded, randomized controlled studies remain limited.3-6

In practice, the application of VST therapy requires identification of viral antigens for pathogen targeting, and isolating and/or expanding VSTs for clinical use.3-8 Early foundational studies in cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy explored donor-derived and third-party VST products, with a focus on herpesviruses, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).8-18 Building on these strategies, subsequent studies have expanded the use of VSTs to treat adenovirus (Adv), as well as organ-specific viral infections such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and BK virus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis.8,19-22 As VSTs move from the clinical trial space to standard clinical care, the promise of VST therapy hinges on improved accessibility and establishing its effectiveness through comprehensive randomized clinical trial protocols.6,15,23

Methods of VST production

Donor-derived VST products use the HCT donor for both HCT graft and VST production. In contrast, third-party VST therapy uses products previously generated from partially HLA-matched healthy donors. Autologous VSTs have also been used in the SOT and HIV settings.24,25 Cord blood–derived VSTs represent a particular challenge due to the naïve nature of cord blood T cells. In spite of this, Abraham et al highlighted the early use of cord blood–derived VSTs for prophylaxis and treatment to target multiple viruses simultaneously (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).26

Initial VST studies were dependent on prolonged culture methods, and required live virus-infected cells as antigen-presenting cells for donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), thereby stimulating VST activation and expansion.27,28 This approach is effective and remains in use, but is time intensive, and requires stringent safety measures to prevent live virus contamination of the final clinical product. Recent advances in cellular therapy have reduced the manufacturing time, and replaced live viral transduction with viral peptide libraries.29,30 Currently, rapid expansion and immunomagnetic selection represent the most common methods of VST manufacturing.31,32 Importantly, both rapid expansion and direct isolation are dependent on robust preexisting immunity in the VST donor.

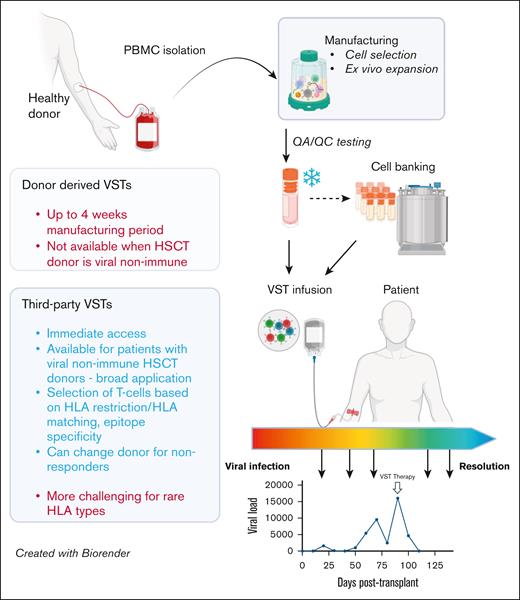

For rapid VST expansion, donor PBMCs are stimulated with viral peptides. Antigen-presenting cells in PBMCs, including monocytes and B cells, then present viral peptides to T cells, leading to their activation and proliferation. The stimulated VST population expands in the presence of cytokines, maximizing T-cell growth and functionality (Figure 1). Rapid expansion protocols have reduced the time requirement for ex vivo expansion from several weeks to 10 to 12 days, and arrays of cytokine conditions have been used to optimize the phenotype of expanded VST products to suit the targeted pathogen.33

Comparison of functional and operational characteristics between donor-derived and third-party VSTs. VSTs can be manufactured from PBMCs from HSC donors (left) or healthy third-party donors (right) using similar methods, including cell selection or ex vivo expansion. Following required quality assurance/control testing, VSTs can be cryopreserved for either directed use or banking, and infused into patients for either prevention or treatment of targeted viral infections. Response assessment is dependent on trending of viral polymerase chain reactions, though correlative studies of cellular responses to viral antigens may also be useful when available. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; QA/QC, quality assurance/quality control. Figure created with BioRender.com. Djassemi N. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/66fef6394004c2128b84bcb1.

Comparison of functional and operational characteristics between donor-derived and third-party VSTs. VSTs can be manufactured from PBMCs from HSC donors (left) or healthy third-party donors (right) using similar methods, including cell selection or ex vivo expansion. Following required quality assurance/control testing, VSTs can be cryopreserved for either directed use or banking, and infused into patients for either prevention or treatment of targeted viral infections. Response assessment is dependent on trending of viral polymerase chain reactions, though correlative studies of cellular responses to viral antigens may also be useful when available. HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; QA/QC, quality assurance/quality control. Figure created with BioRender.com. Djassemi N. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/66fef6394004c2128b84bcb1.

Alternatively, VSTs may be directly isolated from the peripheral blood of donors.23,34-40 In this process, VSTs are directly collected using HLA multimers or by immunomagnetic selection based on expression of interferon gamma after viral peptide stimulation. Once isolated and purified, these cells can be directly infused into the patient. Using immunomagnetic selection, directly isolated VSTs are available in a single day, as compared with weeks for rapid expansion. Direct isolation is limited by access to specialized technology and low cell yield. Furthermore, use of multimer isolation requires a deep understanding of immunodominant epitopes and HLA restrictions for targeted viruses.35 Despite these challenges, direct isolation remains a promising approach for the rapid generation of VSTs in situations where time to product infusion is critical for the patient.

Case 1: donor-derived VSTs

An 11-year-old boy from Honduras with X-linked, mosaic severe combined immunodeficiency due to a pathogenic, hemizygous IL2RG variant presented with multiple infectious complications, including bronchiectasis and CMV pneumonitis and retinitis. Pretransplant bronchoscopy confirmed multiple infections, including low-level CMV, Adenovirus(Adv), respiratory syncitial virus, rhinovirus, and polymicrobial bacterial pneumonia, all of which were treated before HCT.

He underwent haploidentical transplantation from his mother following conditioning with rabbit antithymocyte globulin (rATG), busulfan, and fludarabine, followed by an α/β T-cell/CD19+ B-cell depleted graft. Antiviral prophylaxis began on day −9, with weekly cidofovir provided initial control of Adv DNAemia. Engraftment syndrome developed by day +7, requiring high-dose glucocorticoids for respiratory distress, resulting in a marked worsening of Adv DNAemia. Cidofovir was escalated to 3 times weekly, but viremia continued to rise. Unfortunately, chimerism studies on day +26 confirmed graft rejection (0% donor cells).

A second haploidentical related transplant was performed with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rATG, and total body irradiation. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of posttransplant cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and sirolimus. Both donor and recipient were CMV+, but their EBV status was discordant (EBV– recipient, EBV+ donor).

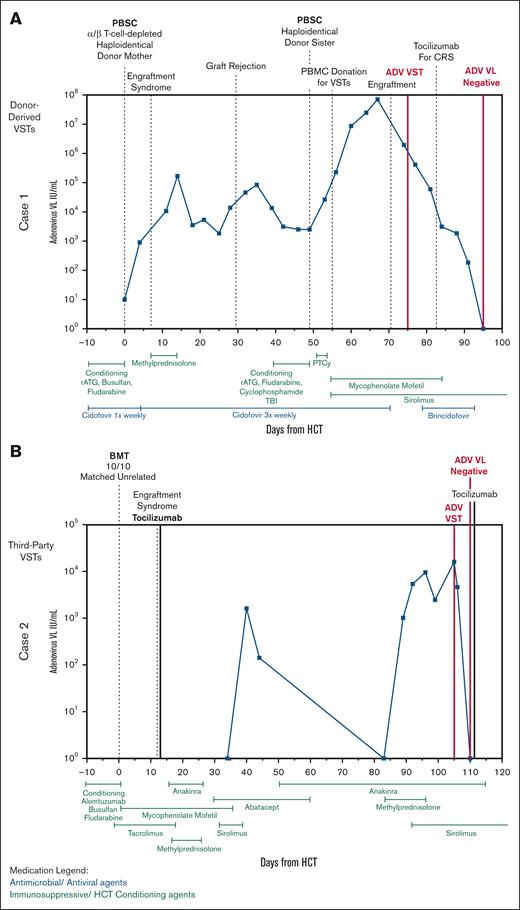

Adv DNAemia worsened despite cidofovir during second transplant. Given his deteriorating clinical status, including respiratory distress concerning for adenoviral pneumonia and acute kidney injury due to prolonged high-dose cidofovir, he was referred for compassionate use of brincidofovir and VST therapy (Figure 2A). As anticipated, cidofovir remained ineffective, and Adv DNAemia continued to rise after the second transplant. Lymphocyte counts before VST infusion were as expected after HCT, with a peak in absolute lymphocyte count of 300 cells × 109/L on day +24. He received Adv-specific donor-derived VSTs on day +26 from second transplant (day +75 from first HCT), ∼4 days after engraftment.

Clinical courses of patients 1 and 2. (A) Clinical course of patient 1 with X-severe combined immunodeficiency who received donor-derived Adv-specific VSTs after their second HCT with resolution of Adv. (B) Clinical course of patient 2 with combined immunodeficiency who received third-party–derived trivalent VSTs specific for EBV, CMV, and Adv for the treatment of Adv. BMT, bone marrow transplant; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide; VL, viral load.

Clinical courses of patients 1 and 2. (A) Clinical course of patient 1 with X-severe combined immunodeficiency who received donor-derived Adv-specific VSTs after their second HCT with resolution of Adv. (B) Clinical course of patient 2 with combined immunodeficiency who received third-party–derived trivalent VSTs specific for EBV, CMV, and Adv for the treatment of Adv. BMT, bone marrow transplant; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide; VL, viral load.

He experienced grade 1 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) after VST therapy, for which he received a single dose of tocilizumab on day +34. By day +37, his Adv DNAemia began to decline rapidly. Given his severity of illness, brincidofovir was also initiated, although viremia had already significantly improved. His DNAemia resolved by day +46, 3 weeks after initiation of VST therapy, with concurrent improvement in oxygen requirements and fever curve. T-cell activity against adenoviral antigens improved by day +126 after VST infusion based on interferon gamma enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (supplemental Figure 1).

Donor-derived VSTs

In this case, donor-derived VST therapy was given after standard antiviral treatment failed to control the recurrence of severe Adv DNAemia in the setting of worsening clinical status and antiviral toxicities. Data support the use of VSTs in patients with complex viral histories who fail conventional antiviral therapies in peri-HCT.41,42 In this case, cells were obtained from the donor within days of collection of cells for second transplant. With graft rejection, severe viral infections, and significant morbidity from the first HCT, the need for donor-derived VSTs was anticipated during second transplant. Donor-derived VSTs were chosen to support the new donor graft, especially in light of the recent graft rejection. Adv VSTs were administered on day +28 from second transplant to minimize elimination by rATG due to its potentially long half-life.43

Response rates

Donor-derived VSTs have led to rapid and durable responses in post-HCT viral infections. Studies suggest that earlier VST infusion, before end-organ dysfunction, can significantly reduce viremia and prevent clinical decompensation.44,45 Compared with third-party VSTs, donor-derived VSTs may be given earlier in the HCT course due to lower risk of graft rejection, although the use of serotherapy must be considered, as it could deplete infused VSTs.46 Additionally, HLA restriction is a key determinant of VST efficacy, as antiviral T-cell activity depends on shared HLA molecules for antigen presentation.41,47,48 Response rates, defined by reduction in viremia, vary from 60% to 90%, with most responses occurring within 28 days of infusion (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Immunosuppressive agents in the peri-HCT setting may influence response rates; notably moderate-to-high-dose glucocorticoids and serotherapy within 28 days are exclusionary in most VST studies.49

Case 2: third-party VSTs

A 10-year-old girl with cartilage hair hypoplasia characterized by T-cell lymphopenia, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and rubella-associated granulomatous leg lesions underwent a 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor transplant with reduced-toxicity conditioning, including alemtuzumab, busulfan, and 10% reduced fludarabine due to presumed rubella central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Her CMV serostatus was negative; however, she was started on CMV prophylaxis due to discordance with her CMV+ donor. She had no additional viral risk factors including EBV.

Her posttransplant course was complicated by shock on day +12 due to suspected engraftment syndrome with multiorgan failure, requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure and continuous renal replacement therapy for severe acute kidney injury in the setting of BK hemorrhagic cystitis. Anakinra was administered for chronic idiopathic fevers. By day +92, amid multisystem organ dysfunction, her Adv viral load began increasing, reaching 16 033 copies per mL by day +103. Thus, the clinical team felt treatment of Adv DNAemia was indicated; however, her comorbidities, particularly renal dysfunction, precluded cidofovir use. She was referred for VST therapy (Figure 2B).

Our patient received third-party CMV/EBV/Adv-specific VSTs on +day 105. Days before VST infusion, her CD4+ T-cell count was 61 cells x10^9/L, with a peak in Adv DNAemia viral load within a week of VST infusion. Profound lymphopenia persisted (absolute lymphocyte count range, 160-480 cells per μL) during this period (days +96 to +110). Despite this, she had a rapid decline in her Adv DNAemia, with complete resolution of infection within 5 days of VST administration. T-cell activity against adenoviral antigens was detectable at baseline, but improved by day +195 (supplemental Figure 2). She had no CMV or EBV reactivation, and VSTs were well tolerated. As of 12 months after HCT, she has had no recurrence of Adv DNAemia.

Third-party–derived VSTs

Case 2 illustrates the potential benefits of using third-party–derived VST therapy as an “off-the-shelf” intervention when donor-derived VSTs are not available. Indications for third-party VSTs include matched unrelated donors when additional donations are impossible or when VSTs cannot be manufactured in time to meet patient needs.9,13-15,50-58 Whereas donor-derived VSTs can persist for years after infusion, third-party–derived VSTs are typically transient and primarily serve as a bridge to lymphoid reconstitution after HCT. Therapeutic response rates for third-party VST therapy vary widely, ranging from 50% to >90%. Additionally, multi–virus-specific VSTs may provide enhanced control over monovalent VSTs in complex cases.51,59-61 Although median times to response vary from 2 to 4 weeks, rapid responses as in this case are possible, particularly in the setting of emerging graft immune reconstitution. Fabrizio et al demonstrated that an absolute CD4+ count >50 cells x10^9/L correlated with improved VST response and overall survival, supporting the importance of immune reconstitution for VST efficacy.62 In this case, the expediency of third-party VST administration was pivotal in averting further complications. Thus, an off-the-shelf third-party product was the optimal choice over donor-derived VSTs.

VSTs in SOT

The extension of VST use into the SOT space presents unique challenges. VSTs for SOT recipients are generated autologously or from partially HLA-matched third-party donors.14,25,55,63-68 Compared with other populations, SOT recipients are typically more immunocompetent, which may accelerate rejection of allogeneic cells, limit VST engraftment, and potentially reduce response rates. Although autologous VSTs mitigate the risk of rejection, their generation can be challenging depending on the patient’s underlying immunologic status. Additionally, SOT recipients are maintained on iatrogenic immunosuppression to prevent organ rejection, with the intensity determined by (1) type of solid organ graft, (2) time since SOT, and (3) infectious complications.69 The relative impact of SOT-related immunosuppression on VSTs, compared with GVHD prophylaxis in HCT, remains unclear. Immunosuppressive medications may directly impair VST function, reducing antiviral efficacy, whereas others may prolong persistence by delaying immune-mediated rejection. These competing factors make predicting VST responses in SOT recipients particularly complex. VSTs in SOT have primarily targeted EBV, CMV, Adv, and BK virus.12,13,15,53,55,63,65,66,70-73 Clinical trials have focused on high-risk viral complications: EBV-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD), which is most common in intestinal and multivisceral SOT, CMV viremia, end-organ disease (notably in lung transplant), and BK virus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis or graft rejection.55,65,73-75 Although VST therapy in SOT has largely focused on treatment of viremia or end-organ transplant, prophylactic VSTs for EBV PTLD have also been explored.25 Experience with VST therapy in SOT has spanned both adult and pediatric populations requiring renal, cardiac, liver, lung, pancreas, and multiorgan transplants.12-14,25,53,70 Most studies did not require immunosuppression reduction before VST infusion beyond prednisone dose limitations and recent antithymocyte serotherapy, similar to HCT restrictions. Successful VST therapy has been administered alongside agents such as calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites (mycophenolate, azathioprine), recombinant soluble CTLA-4–immunoglobulin, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.12-14,53,55,68,73

In studies including both HCT and SOT recipients, SOT recipients typically had lower response rates and required more VST cycles than their HCT counterparts, though not universally (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).13,14 Detecting VSTs after infusion has been challenging in this population, yet, persistent allogeneic VSTs have been observed in select individuals for up to 2 years.12-14,64,76 Notably, clinical response rates in SOT have been generally higher than rates of detectable VST persistence, suggesting that allogeneic VSTs may induce endogenous virus-specific T-cell responses through costimulation.14,73

IEIs

As highlighted in the clinical cases, patients with IEIs impacting T-cell function are at risk of prolonged and potentially severe viral infections, which are an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality after HCT.77 Most VSTs in IEI have been given in the setting of HCT, but several studies have documented attempts to use partially HLA-matched VSTs outside of HCT, usually alongside antiviral therapy. Thus far, no sustained responses in patients with IEI have been described outside of the setting of HCT; however, 3 patients with severe viral disease successfully received VSTs as a bridge to HCT.49,78-81 Rubinstein et al described 2 patients with ataxia-telangiectasia and EBV-associated lymphoma who experienced transient partial responses to EBV-specific T-cell therapy before eventual disease progression.82 Theories regarding the poorer outcomes before HCT include the possibility of VST exhaustion in the absence of broader immune reconstitution and/or transient engraftment in patients with dysfunctional but nonabsent T-cell immunity. Notably, successful use of VST therapy for patients with rare IEI with PML suggests that clinical responses are possible in this population.19 Further studies are needed to better define the key factors influencing response rates in this population.

Safety considerations

CRS

CRS, though common after infusion of chimeric antigen receptor T cells, is rare after VST therapy. However, CRS has been reported, particularly in patients with advanced viral disease or bulky EBV PTLD.49,83 As in chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, these reactions represent exuberant on-target effects, are often associated with VST expansion in vivo, and can lead to life-threatening complications.

In a recent Children's Oncology Group study of latent membrane protein-specific T cells for EBV PTLD after SOT, 2 cases of grade 1 CRS resolved without treatment, whereas 1 patient developed grade 3 CRS followed by fulminant disease progression.67 Likewise, in a recent phase 2 study of partially HLA-matched VSTs in 51 immunocompromised pediatric patients, 1 case of grade 3 CRS occurred 10 days after VST infusion for refractory Adv, followed by fatal viral progression.49 As observed in case 1, mild to moderate CRS can be managed with supportive care and tocilizumab monotherapy without compromising VST efficacy.

Fatal CRS after VST therapy has also been reported. Holland et al described a DOCK8-deficient patient with severe BK virus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis who received multi–virus (CMV/EBV/Adv/BK virus)-specific T-cell therapy.84 The first VST infusion before HCT was well tolerated but ineffective, leading to severe hemorrhagic cystitis and renal hemorrhage requiring embolization. On day +45 after HCT, a second dose of VST was administered, followed by grade 4 CRS on day +47, which was refractory to tocilizumab, culminating in multiorgan failure, hepatic veno-occlusive disease, and death.

GVHD

When administering allogeneic T cells, GVHD remains a primary concern. However, unlike donor lymphocyte infusion, the incidence and severity of GVHD after VST infusion are generally low.11 Though rates of GVHD in previous VST studies vary widely, ranging from 0% to 54% (supplemental Tables 1 and 2), attribution of GVHD after HCT is challenging. Most studies have excluded patients with significant, active GVHD at the time of infusion, because VSTs would likely be inactivated by concurrent escalations of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, the absence of randomization and control arms prevents definitive conclusions regarding the impact of VSTs on GVHD risk. Presently, no validated correlative test exists for in vivo alloreactivity. In previous studies, alloreactivity of VSTs is demonstrable in vitro, but has not equated to actual risk for patients.85

Secondary graft rejection

Similar to GVHD, graft-versus-graft reactions are possible when third-party VSTs are used due to HLA-mismatch between the VSTs and the HCT or solid organ graft in addition to partial mismatch with the recipient. To date, only 1 case of secondary marrow graft rejection attributed to VST infusion has been described.86 Extensive investigation did not identify a causative epitope, though the VST donor—a 46-year-old G2P2 woman—was hypothesized to have contributed to rejection due to allosensitization.87,88 No additional cases of VST-associated graft rejection have been reported internationally. This case report led to exclusion of third-party VST donors with risk of allosensitization (including multiparous women) in our program. In the setting of partially HLA-matched, third-party VSTs for SOT recipients, organ rejection has been observed, but has not been definitively linked to VST therapy.53,55,63,89

Other rare adverse effects

Rare cases of severe neurologic disease have been described in recipients of third-party VSTs. Keller et al described 2 patients who developed progressive neurologic complications after receiving third-party VSTs for disseminated Adv, including seizures, altered mental status, diffuse axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy, diffuse white matter abnormalities, and subdural hemorrhage.49 One patient had a recent history of transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), a condition that may be associated with CNS manifestations, whereas transplant-associated TMA was not ruled out in the second case. Although no association between VST infusion and TMA has been established, both TMA and eculizumab treatment were identified as risk factors for nonresponse to VST therapy in the ACES study.49 VSTs have been used successfully for other CNS diseases, including CNS PTLD and PML without similar adverse events.15,76 Khanna et al reported a single case of EBV PTLD treated with autologous VSTs in which necrosis of the PTLD invaded a bronchial vein, leading to fatal hemorrhage.90 On-target pulmonary toxicity, including hypoxia, has been reported after CMV-specific VST infusion, likely due to T-cell trafficking and localized inflammation in infected lung tissue.52 These cases highlight the importance of monitoring for potential on- or off-target toxicities.

Discussion

For 3 decades, VST therapy has been utilized in clinical trials, and substantial progress has been made in terms of manufacturing and application. However, limitations remain regarding accessibility and establishment of best practices to improve the understanding of the true risk and benefits of VST therapy in different clinical settings.

Limitations

VST therapy, although effective, is not widely available outside specialized centers. The expense and technical skill for good manufacturing practice–compliant facilities and highly trained personnel for isolating and/or expanding VSTs from donors restricts its widespread use. As an unapproved medical product, regulatory requirements represent a significant hurdle, making it difficult to implement VST therapy in diverse clinical settings. To date, no VSTs have obtained regulatory approval in the United States, the cause of which is multifactorial, including limited market and lack of successful randomized controlled trials. Posoleucel received orphan drug designation from the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of BK hemorrhagic cystitis in 2021, and Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy for the treatment of Adv in the HCT setting in 2022. However, phase 3 trials of posoleucel were closed early due to inability to meet primary efficacy end points. Future randomized controlled trials may facilitate eventual approval of the first VST therapy in the United States.

The efficacy of VST therapy may be influenced by factors such as donor T-cell physiology and concurrent immunosuppressive or cytolytic medications. Calcineurin inhibitors have generally not been noted to impact VST efficacy. High-dose corticosteroid therapy and anti–T-cell serotherapy have been tied to viral reactivation and reduced VST responses in several prior studies, but further investigation is warranted to evaluate the dose-response impact of specific corticosteroids on antiviral T-cell function.45,91-94 Newer immunosuppressive therapies including JAK inhibitors are anecdotally associated with failure of VST therapy at standard treatment doses. Thus, anti–T-cells serotherapy, high-dose glucocorticoids, and JAK inhibitors are frequent exclusion criteria for VST clinical trials, whereas other immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory medications are permitted.

As the majority of studies of VSTs have occurred in the HCT setting, other applications including SOT recipients and patients with IEI require additional study to better delineate factors influencing efficacy, including engraftment and expansion of VSTs and their impact on viral infections in the setting of chronic immunosuppression or intrinsic immunodeficiency.

For many patients, especially those with rare HLA types or mismatched transplants, finding suitable third-party donors can be difficult. Additionally, selection of partially HLA-matched VSTs remains a highly subjective process, and overall degree of HLA match has not correlated with chances of clinical responses in previous studies.49,52 Previous studies have described a hierarchy in cellular epitope recognition particularly for herpesviruses, which could impact the success rate of third-party VST therapy, and requires further study by viral target.48 Furthermore, immunodominant HLA-dependent epitope restrictions are better characterized for common HLA alleles in regions of the world in which VST protocols have been conducted, making VST matching in those populations more evidence based. In the future, strategic selection of third-party donors based on their HLA alleles and specific identification of novel immunodominant viral epitopes and HLA restrictions could facilitate better matching of VST donors and SOT or HCT recipients for third-party therapy, and thereby improve efficacy.41,47,48,95,96

Expanding applications of VSTs: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, emerging viruses, and neonatal treatments

As VST therapeutics have evolved, a diverse range of viral targets for VST are under investigation, including respiratory viruses such as human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04933968), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (NCT04896606). Additional targets include HIV, norovirus (NCT04691622), human papillomavirus (NCT03351855), human herpesvirus 6 (NCT02108522) and Zika virus.97-101 As the interest in VSTs for tissue-based viral diseases increases, there have been concerns about appropriate tissue trafficking and efficacy in the absence of viremia. This challenge is particularly relevant in the CNS, though, as highlighted above, there is evidence supporting use of VSTs for CMV retinitis and JC or BK-specific VSTs for the treatment of PML.102,103

VSTs have rarely been used in neonates, including 1 published case of adenoviremia.104 There is currently an active trial for congenital CMV (NCT05564598). If successful, this could pave the way for further research into the treatment of congenital viral infections with VSTs.

Future considerations

Improving patient outcomes with VSTs depends on advances in both manufacturing and clinical application. Manufacturing conditions, including cytokine cocktails and small molecule therapy, may help to enhance antiviral activity and VST persistence through reduction of terminal differentiation.6 The next frontier of VST therapy will likely involve the integration of VSTs with novel therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor T cells, gene-edited T cells, or even bispecific T-cell engagers. These advanced treatments could offer more targeted and potent responses against both viral infections and associated malignancies. Future studies are needed to evaluate how these innovative therapies can be tailored to individual patients based on their virological and immunological profiles. Additionally, manufacturing and regulatory challenges must be addressed to broaden VST use beyond highly specialized research centers. Through improvement in the application of existing VST therapies alongside new immunologic and antiviral therapies, it may be possible to restore antiviral immunity in a broader range of patients, and thereby reduce the profound morbidity and mortality of viral infections in immunocompromised patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Center for Cancer and Immunology Research and Divisions of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Infectious Diseases, and Allergy and Immunology at Children’s National Hospital, the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation for their support of this work.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of Intramural Research (J.R.D.-S.) and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation (M.D.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: N.D., B.H., A.V., C.M., J.R.D.-S., and M.D.K. wrote and edited the manuscript; N.M. performed research and analyzed data; and all authors approved the final draft.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.D.K. receives authorship royalties from Wolters Kluwer (UpToDate). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael D. Keller, Immunology, Children’s National Hospital, 111 Michigan Ave NW, M5207, Washington, DC 20010; email: mkeller@childrensnational.org; and Jessica R. Durkee-Shock, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr, Building 10, Office 6D44D, Bethesda, MD 20892; email: jessica.durkee-shock@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

J.R.D.-S. and M.D.K. are joint senior authors.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.