In this issue of Blood Advances, Zhai et al1 describe the development of a novel mouse model of hemoglobin SC (HbSC) disease, creating new possibilities for increasing understanding of and developing novel therapies for this neglected disease.

HbSC was first recognized as a distinct form of sickle cell disease (SCD) more than 75 years ago in Michigan when Itano and Neel2 studied 2 unrelated children with mild SCD and only 1 parent with sickle cell trait. In populations of African origin, the HbSC genotype is the second most common form of SCD after sickle cell anemia (HbSS), accounting for ∼30% cases. There are at least 1 million people with the condition in the world,3 although exact numbers are not known and may be significantly greater.

All hemoglobinopathies have been neglected over the years, with poor outcomes, limited facilities for diagnosis and management and few specific treatments. However, until recently HbSC disease has almost been completely ignored as a specific form of SCD. In general, HbSC disease has been considered as a milder form of HbSS and treated in this way. Sometimes it has been excluded from studies of SCD entirely, and although other studies have allowed recruitment of patients with HbSC, the numbers involved have been too small to allow any significant conclusions on specific benefits in HbSC disease.4

Fortunately, it is increasingly recognized that HbSC is not just a mild form of SCD, but a separate condition with distinctive pathophysiology and clinical features. Polymerization of hemoglobin S (HbS) is still central to the pathology, although the concentration of HbS in the red cells is only about 50%, slightly higher than that found in sickle cell trait. The unique pathological process seems to be the induction of erythrocyte cation loss by the action of hemoglobin C on the red cell membrane, resulting in red cell dehydration and the necessarily high concentration of HbS to cause polymerization.5,6 Of major importance appears to be mediation of solute loss through a specific membrane transport system, the KCl cotransporter, which is especially active in red cells from patients with HbSC. Laboratory features of HbSC disease are also very distinct from sickle cell anemia (HbSS) with higher hemoglobin, less hemolyis, low fetal hemoglobin levels, and limited inflammation.

Clinically, HbSC is also distinct from HbSS, with an increased incidence of proliferative retinopathy, and probably some other complications such as acute sensorineural hearing loss and fat embolism syndrome. The incidence of acute vaso-occlusive and vasculopathic complications is lower than in HbSS but still very significant, and in the United States life expectancy is probably reduced by at least 20 years compared to the non-sickle population.7 Outcomes in low-income countries, particularly Ghana where HbSC is most common, are unknown but likely to be very significantly worse. Specific treatments have not been developed for HbSC disease, although data are now starting to emerge about the specific clinical benefits of hydroxycarbamide.8 Venesection to induce iron deficiency and reduce hemoglobin is also quite widely used in some countries, although it is unclear exactly how this should be used.9

Given the distinctive pathophysiology of HbSC disease, it seems very likely that specific drugs targeting erythrocyte dehydration could be developed, although this requires appropriate cellular and animal models. Zhai et al’s work is particularly important in this context. They used the Townes mouse, which contains human globin genes and is one of the main mouse models of HbSS, and using CRISPR technology edited fertilized eggs from Townes HbAA mice to produce mice carrying hemoglobin C (HbC). These mice with HbC trait were cross bred with sickle cell trait Townes mice to create a strain of mice with HbSC. The authors went on to characterize these mice, showing important similarities with HbSC disease in humans. The red cells were dense and dehydrated, and perhaps most importantly the mice showed some evidence of vascular retinopathy after 12 months, although this mostly involved loss of blood vessels rather than the proliferative retinopathy seen in humans. As would be expected, the mouse model also shows some significant differences compared to humans, including more severe anemia and hemolysis and a higher percentage of HbS, with smaller than expected spleens.

Perhaps surprisingly given that we have waited more than 75 years for 1 mouse model of HbSC, Setayesh et al10 also published a study describing the generation of an HbSC mouse model as Zhai et al’s article was being reviewed. This model is also based on the Townes mouse but created in a slightly different way, by directly editing the genome of an HbSS mouse to HbSC. This seems to produce a predictably similar model, but some with differences including less dehydrated red cells and more retinopathy.

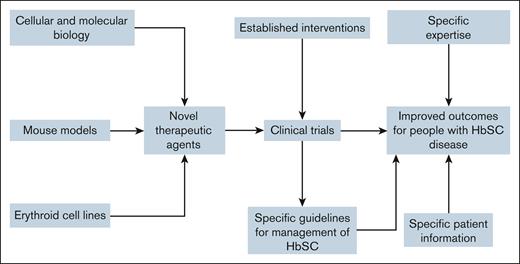

The development of 2 mouse models opens the way for the identification of some novel therapeutic targets in HbSC disease and the development effective drugs (see figure). It seems likely that these targets will include targeting erythrocyte cation loss, although this may be complicated given that these models involve mice red cells, which are significantly smaller than human red cells, and show other differences. Although several important membrane transport proteins are common to mouse and human red cells, notably the KCl cotransporter, Piezo1 and the Gárdos channel, details of their regulation and how they interact with themselves, and also with other important solute transporters, are probably critical to the usefulness of these models. These developments will be facilitated by the simultaneous development of immortalized human erythroid cell lines with HbSC, which are currently being developed in several laboratories around the world, and which potentially provide better models of the cellular pathology.

This increased interest in HbSC disease is hugely encouraging. Nevertheless, it is important that these laboratory developments are paralleled by appropriate clinical studies, including drug trials with statistically significant numbers of patients with HbSC disease, and better understanding of the use of established interventions such as venesection, IV fluids, and inhaled oxygen.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.