Key Points

RTIs with S aureus or SARS-CoV-2 increase plasma VWF levels and decrease ADAMTS13 activity.

VWF may have a causal role in worsening stroke outcomes in RTIs preceding stroke, whereas ADAMTS13 may be protective.

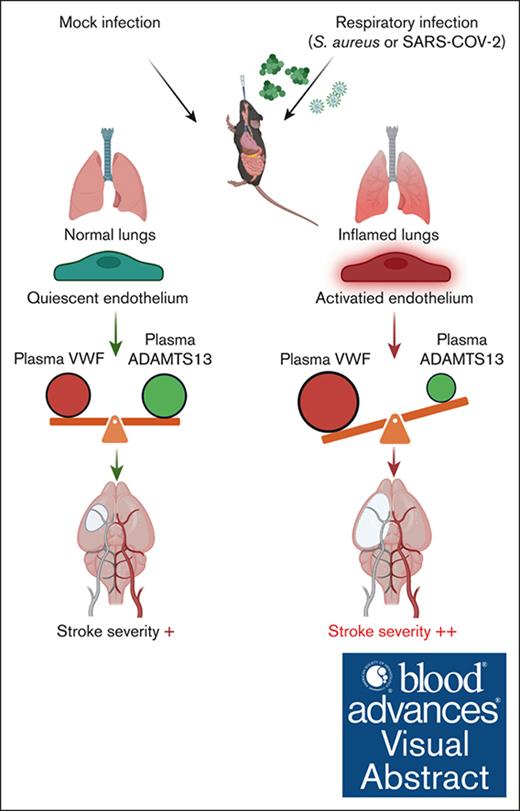

Visual Abstract

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) caused by bacteria or viruses are associated with stroke severity. Recent studies have revealed an imbalance in the von Willebrand factor (VWF)–ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13) axis in patients with RTIs, including coronavirus disease 2019. We examined whether this imbalance contributes to RTI-mediated stroke severity. Wild-type (WT), Vwf−/−, or Adamts13−/− mice with respective littermate controls (Vwf+/+ or Adamts13+/+) were infected intranasally with sublethal doses of Staphylococcus aureus (on days 0, 2, and 5) or mouse-adapted severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; on day 0) and subjected to transient (30 or 45 minutes) cerebral ischemia followed by reperfusion. In S aureus–infected mice, infarct volumes were assessed on day 2 and functional outcomes on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion. In SARS-CoV-2–infected mice, infarct volumes and functional outcomes (Bederson score) were assessed on day 1 after reperfusion. We demonstrated that S aureus or SARS-CoV-2 RTI was accompanied by an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis and an increase in plasma levels of interleukin-6, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which was associated with larger infarcts and worse functional outcomes (P < .05 vs mock infection). S aureus– or SARS-CoV-2–infected Vwf−/− mice exhibited reduced infarcts and improved functional outcomes, whereas infected Adamts13−/− mice displayed greater stroke severity (P < .05 vs control). In the models of RTI preceding stroke, VWF contributes to stroke severity, whereas ADAMTS13 is protective.

Introduction

Nearly 25% to 30% of patients with ischemic stroke with a preceding respiratory tract infection (RTI) caused by bacterial or viral pathogens experience more severe neurological deficits.1,2 Recent studies suggest a link between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and an increased risk of ischemic stroke, particularly within the first 3 days after a COVID-19 diagnosis.2-4 Despite successful treatment of RTIs with antimicrobial agents, preceding RTIs may still increase susceptibility to, or severity of, ischemic stroke by several mechanisms including direct endothelial damage or a systemic inflammatory response, including cytokine storms, promoting endothelial dysfunction. This dysfunction leads to hypercoagulability and thrombotic occlusion of the vessel.5,6

von Willebrand factor (VWF) plays a crucial role in hemostasis and thrombosis by mediating platelet adhesion to the subendothelial matrix and extending the half-life of coagulation factor VIII in plasma. The functional activity of VWF depends on its molecular size, which is regulated by ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13). Experimental studies suggest that ADAMTS13 deficiency exacerbates ischemic stroke,7,8 whereas VWF deficiency provides protection.7,9,10 Likewise, epidemiology studies demonstrate that increased VWF levels and reduced ADAMTS13 activity increase the risk of ischemic stroke.11-13 Notably, it has been shown that pathogens causing community-acquired RTIs, such as Staphylococcus aureus, can severely impact the hemostatic system,14 increasing plasma VWF levels and decreasing ADAMTS13 activity.15 COVID-19 has also been associated with similar VWF-ADAMTS13 imbalances that correlate with disease severity.16-18 Despite these studies, it remains unclear whether the imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis is a mediator of S aureus– or COVID-19–associated stroke severity or merely reflects disease status.

In this study, we hypothesized that an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis serves as a pathogenetic mechanism by which RTIs of varying etiologies exacerbate ischemic stroke severity and worsen outcomes. To test this hypothesis, we infected mice with frequent yet fundamentally different RTI-causing pathogens, S aureus or mouse-adapted severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), subjected them to experimental ischemic stroke, and examined the impact of these infections on the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, stroke severity, and long-term functional outcomes.

Methods

Detailed information on materials and methods is provided in the supplemental Data

Mice

Wild-type (WT) mice on C57BL/6J were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The Vwf−/−19 and Adamts13−/−20 mice used in this study were derived by intercrossing Vwf+/− or Adamts13+/− mice, respectively, and were on the C57BL/6J genetic background. Controls were littermates Vwf+/+ or Adamts13+/+. Mice were kept in standard animal housing conditions with controlled temperature and humidity and had ad libitum access to a standard chow diet and water. Male, 3- to 4-month-old mice were used. We did not use female mice because of infarct size variability associated with the estrous cycle and protection against ischemic stroke.21,22 The University of Iowa animal care and use committee approved all the procedures, and studies were performed according to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments 2.0 guidelines.

Infection by S aureus

S aureus (USA300 strain) or phosphate-buffered saline (mock infection, 50 μL) was challenged intranasally in ascending doses on day 0 (108 colony-forming unit [CFUs]), day 2 (2 × 108 CFUs), and day 5 (4 × 108 CFUs) to mice anesthetized by ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Body weight was recorded daily to confirm the severity of the infection. On day 6 after infection, brain or lung homogenates or blood was spread on agar plates and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C for organ load of S aureus.

Infection by SARS-CoV-2

In mice anesthetized by ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 (SARS2-N501YMA30, SARS-CoV-2) or phosphate-buffered saline (mock infection, 50 μL) were challenged intranasally on day 0. Body weight was recorded daily to confirm the severity of the infection. Experiments related to SARS-CoV-2 were performed in a biosafety level 3 facility at the University of Iowa. SARS-CoV-2 was titered in the lungs and brain by plaque assay on day 3 after infection. Plaque assay was performed as previously described.23 Briefly, 12-well plates of Vero E6 cells with the serially diluted virus were inoculated at 37°C and gently rocked every 10 minutes for 1 hour. After removing the inocula, plates were overlaid with 0.6% agarose. After 3 days, cells were fixed in 25% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for >20 minutes at room temperature, then the overlays were removed, and plaques were visualized by staining with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 minutes. Viral titers were quantified as plaque-forming unit (PFU) per milliliter.

Plasma VWF levels

VWF antigen was measured via sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Mouse heparinized plasma was diluted (1:40) with sample diluent (5% bovine serum albumin) and added to wells precoated with diluted (1:2000) rabbit anti-human VWF as primary antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Samples were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C, followed by washing, and then further incubated with 1:10 000 diluted horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-VWF as a secondary antibody (Dako). The horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate (Tetramethylbenzidine-) was added, and the reaction was stopped after 30 minutes by adding a stopping solution. The absorbance was measured at wavelength 450 nm. VWF levels were compared with pooled plasma from WT mice (as 100%) and results were expressed as a percentage of WT values.

Plasma ADAMTS13 activity

ADAMTS13 activity was determined by fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay using a FRETS-rVW71, as previously described.24 ADAMTS13 activity was compared with pooled plasma WT mice (as 100%), and results were expressed as a percentage of WT values.

Filament model of cerebral ischemia

Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by transiently occluding the right middle cerebral artery for 30 or 45 minutes, as previously described.25 All surgeries were performed by the person blinded to the experimental groups. Mice were anesthetized with 1% to 1.5% isoflurane mixed with medical air. Bupivacaine (5 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously on the incision line. After a midline incision, the right common carotid artery was temporarily clamped, and a silicon monofilament (Doccol, catalog no. 702256PK5) was inserted via the external carotid artery into the internal carotid artery up to the origin of the middle cerebral artery. Reperfusion was achieved by removing the filament after 30 or 45 minutes and opening the common carotid artery. Throughout the surgery, the body temperature of mice was maintained at 37°C ± 0.5°C using a heating pad. Mice with hemorrhagic transformations within 24 hours of surgery or bleeding during surgery or surgery time >15 minutes were excluded from the study (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

MRI imaging of the brain

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on day 2 after reperfusion, as previously described.25 Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5% induction, 1.2% maintenance) and placed in the bore of the 7.0 Tesla MRI (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA) with a 2-channel receive-only surface coil. After scout scans, high-resolution images were acquired with a 9-minute T2-weighted 2-dimensional fast spin-echo sequence oriented coronally. Imaging parameters included repetition time (TR)/ echo time (TE) = 6380 milliseconds/83 milliseconds, echo train length of 12, and 7 signal averages to achieve voxel resolution 0.10 mm × 0.10 mm × 0.50 mm with no gaps. The total imaging time for each animal was ∼25 minutes.

Infarct area quantification

The infarction volume was quantified by the person blinded to the experimental groups using the National Institutes of Health ImageJ software by outlining the zone with abnormally hyperintense regions in each brain slice. The total infarct volume was obtained by summating the infarct volume multiplied by the slice thickness.

Statistical analysis

The number of experimental animals in each group was selected based on power calculations (using mean differences and standard deviations from pilot data at power 80% with an α of .05 for infarct volume) or previously published studies. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism (version 10.2.3 for Windows; GraphPad Software, Boston, MA) and R software (version 4.3.3). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean if normally distributed or as median (range or interquartile range, as indicated) if nonnormally distributed. Normality was evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were presented as counts. Comparisons between 2 independent groups for continuous variables at a single time point were performed with the t test if normally distributed or the Mann-Whitney U test if nonnormally distributed. Comparisons between 2 independent groups for continuous variables at ≥2 time points were performed with a 2-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA; with “Group” as a between-subjects factor and “Time” as a within-subjects factor) followed by the Šidák post hoc test if normally distributed or with the aligned rank transform 2-way mixed ANOVA (a nonparametric alternative of a 2-way mixed ANOVA performed with the “ARTool” R package) if nonnormally distributed. Two-tailed P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sustained S aureus infection induces an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, triggers systemic inflammatory response, and worsens stroke outcomes

Male WT mice (aged 3-4 months) were infected intranasally with a single sublethal dose of S aureus (4 × 108 CFUs). In a subset of mice, on day 1 of infection, plasma VWF levels, ADAMTS13 activity, and inflammatory markers were measured. Another subset of infected mice were subjected to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAo), with infarct volume evaluated 48 hours after reperfusion (supplemental Figure 1A). Infected WT mice exhibited an increase in plasma VWF levels (∼1.5-fold vs baseline, P < .05) and VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (P < .05), whereas ADAMTS13 activity was comparable (supplemental Figure 1B). Plasma levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) remained comparable with those in mock-infected WT mice (supplemental Figure 1C). Infarct volumes were comparable between the S aureus– and mock-infected WT mice (supplemental Figure 1D), suggesting that a single dose of S aureus induced only a mild systemic response that did not impact stroke severity.

Next, we examined whether sustained S aureus infection would trigger a more extensive systemic response, potentially exacerbating ischemic injury. To test this, WT mice were infected intranasally with increasing sublethal doses of S aureus (1 × 108, 2 × 108, and 4 × 108 CFUs per mouse) on days 0, 2, and 5 (Figure 1A). Body weight was recorded daily up to day 6 as a general marker of infection severity and overall health, showing a persistent reduction beginning on day 1. On day 6 of infection, the mice were further evaluated for pulmonary inflammatory index, lung histological score, bacterial loads, plasma VWF levels, ADAMTS13 activity, and cytokine levels. The sustained infection led to a significantly elevated pulmonary inflammatory index (P < .05; Figure 1B), along with a higher lung score (supplemental Figure 7A). Bacterial load analysis confirmed that the infection was limited to the lungs, with no detectable S aureus in the brain or blood (Figure 1B). The infection was accompanied by an increase in plasma VWF levels and a decrease in ADAMTS13 activity (both P < .05), resulting in a ∼2.5-fold increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (Figure 1C). The infected mice exhibited increased plasma levels of IL-6, CXCL-1, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1; P < .05). There was a trend toward an increase in tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), but it was nonsignificant in the predefined sample size. (Figure 1D). These findings indicate that sustained S aureus infection induced a more pronounced systemic inflammatory response when compared with single-dose infection.

RTI caused by S aureus reduced body weight, imbalanced VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, and increased plasma IL-6, CXCL-1, and MCP-1. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: body weight changes in S aureus–infected and mock-infected mice (n = 6-8 mice per group). Middle left: representative MRI images on day 6 after infection; white area indicates inflammation, arrows indicate inflammation. Middle right: pulmonary inflammatory index quantification (n = 6-8 mice per group). Right: bacterial count in the lungs, brain, and blood (n = 8 mice per group). (C) Plasma VWF levels (left), ADAMTS13 activity (middle), and VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (right) on day 6 after infection (n = 6-8 mice per group). (D) Plasma TNF-α (left), IL-6 (middle left), CXCL-1 (middle right), and MCP-1 (right) levels on day 6 after infection (n = 6-8 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panel B (left) and an unpaired t test for panels B (middle),C-D. NS, nonsignificant.

RTI caused by S aureus reduced body weight, imbalanced VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, and increased plasma IL-6, CXCL-1, and MCP-1. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: body weight changes in S aureus–infected and mock-infected mice (n = 6-8 mice per group). Middle left: representative MRI images on day 6 after infection; white area indicates inflammation, arrows indicate inflammation. Middle right: pulmonary inflammatory index quantification (n = 6-8 mice per group). Right: bacterial count in the lungs, brain, and blood (n = 8 mice per group). (C) Plasma VWF levels (left), ADAMTS13 activity (middle), and VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (right) on day 6 after infection (n = 6-8 mice per group). (D) Plasma TNF-α (left), IL-6 (middle left), CXCL-1 (middle right), and MCP-1 (right) levels on day 6 after infection (n = 6-8 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panel B (left) and an unpaired t test for panels B (middle),C-D. NS, nonsignificant.

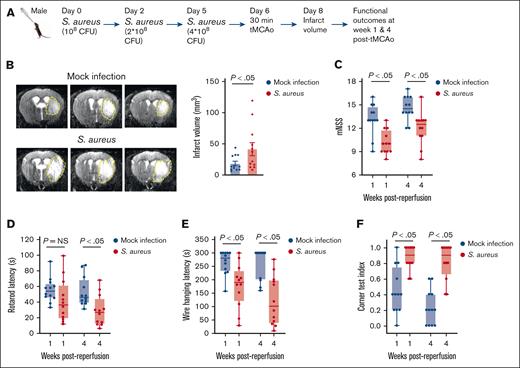

To investigate the impact of sustained S aureus infection on stroke severity, a subset of WT mice was subjected to tMCAo on day 6 of infection, with infarct volume evaluated on day 2 after reperfusion and functional outcomes at weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (Figure 2A). Experiments showed a significant increase in infarct volume in infected mice (P < .05 vs mock infection; Figure 2B). Functional assessments included the modified neurological severity score, a composite score evaluating spontaneous activity, limb movement symmetry, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch; as well as sensorimotor tests such as the corner test index, rotarod test, and wire hanging test. The assessment revealed a significant reduction in all 4 tests in infected mice (P < .05 vs mock infection; Figure 2C-F), indicating worsened long-term functional outcomes.

RTI caused by S aureus worsens stroke outcomes in WT mice. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative T2 MRI images of the brain (coronal) of 1 mouse of each group on day 2 after reperfusion. The white (demarked by yellow dots) indicates an infarct area. Right: infarct volume quantification (n = 12 mice per group). (C-F) Functional outcomes in the same groups of mice on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (n = 12 mice per group). (C) Modified neurological severity score (mNSS) in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). (D-F) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice was analyzed by motor strength in the accelerated rotarod test (D), hanging wire test (E), and corner test, in which a lower corner index indicates better outcome (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for panel B or median and range for panels C-F. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test for panel B and a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panels C-F. NS, nonsignificant.

RTI caused by S aureus worsens stroke outcomes in WT mice. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative T2 MRI images of the brain (coronal) of 1 mouse of each group on day 2 after reperfusion. The white (demarked by yellow dots) indicates an infarct area. Right: infarct volume quantification (n = 12 mice per group). (C-F) Functional outcomes in the same groups of mice on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (n = 12 mice per group). (C) Modified neurological severity score (mNSS) in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). (D-F) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice was analyzed by motor strength in the accelerated rotarod test (D), hanging wire test (E), and corner test, in which a lower corner index indicates better outcome (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for panel B or median and range for panels C-F. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test for panel B and a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panels C-F. NS, nonsignificant.

A separate subset of infected mice was evaluated on day 6 of infection and on days 13 and 34 (mirroring assessments at weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion in mice subjected to tMCAo) to determine whether sustained S aureus infection alone could affect the functional outcomes. No significant differences in functional outcomes were observed between infected and mock-infected mice at any time point (supplemental Figure 2), indicating that sustained S aureus infection did not independently affect functional outcomes in mice after experimental ischemic stroke and served as a predisposing factor.

VWF deficiency improves, whereas ADAMTS13 deficiency worsens stroke outcomes in mice with preceding sustained S aureus infection

To determine the role of the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis in RTI-mediated stroke severity, we used Vwf−/− and Adamts13−/− mice along with their respective controls (Vwf+/+ and Adamts13+/+). On day 6 of sustained S aureus infection, Vwf−/− and Vwf+/+ mice were subjected to tMCAo, and infarct volumes and functional outcomes were evaluated at the same time points (week 1 and 4) used in WT mice (Figure 3A). We found that infected Vwf−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced infarct volumes (Figure 3B) and improved long-term functional outcomes (Figure 3C-F) compared with infected Vwf+/+ controls (P < .05). A similar approach was taken with Adamts13−/− and control Adamts13+/+ mice, infected with S aureus, subjected to tMCAo, and evaluated for stroke severity (Figure 4A). Infected Adamts13−/− mice exhibited increased infarct volumes (Figure 4B) and worsened long-term functional outcomes (Figure 4C-F) compared with infected Adamts13+/+ mice (P < .05). Noteworthy, S aureus–infected Adamts13−/− mice also demonstrated a more significant reduction in body weight compared with Adamts13+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 3), suggesting a more severe systemic response to infection.

VWF deficiency improves stroke outcomes with preceding RTI by S aureus. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative T2 MRI images of the brain (coronal) of 1 mouse of each group on day 2 after reperfusion. The white (demarked by yellow dots) indicates an infarct area. Right: infarct volume quantification (n = 12-13 mice per group). (C-F) Functional outcomes in the same groups of mice on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (n = 12-13 mice per group). (C) mNSS in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). (D-F) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice as analyzed by motor strength in the accelerated rotarod test (D), hanging wire test (E), and corner test, in which a lower corner index indicates better outcome (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for panel B or as median and range for panels C-F. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test for panel B and a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panels C-F. NS, nonsignificant.

VWF deficiency improves stroke outcomes with preceding RTI by S aureus. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative T2 MRI images of the brain (coronal) of 1 mouse of each group on day 2 after reperfusion. The white (demarked by yellow dots) indicates an infarct area. Right: infarct volume quantification (n = 12-13 mice per group). (C-F) Functional outcomes in the same groups of mice on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (n = 12-13 mice per group). (C) mNSS in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). (D-F) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice as analyzed by motor strength in the accelerated rotarod test (D), hanging wire test (E), and corner test, in which a lower corner index indicates better outcome (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for panel B or as median and range for panels C-F. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test for panel B and a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panels C-F. NS, nonsignificant.

ADAMTS13 deficiency worsens stroke outcomes with preceding RTI by S aureus. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative MRI images of brain (coronal) on day 2 after reperfusion. The white (demarked by yellow dots) indicates an infarct area. Right: infarct volume quantification (n = 11-13 mice per group). (C-F) Functional outcomes in the same groups of mice on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (n = 10-11 mice per group). (C) mNSS in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). (D-F) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice as analyzed by motor strength in the accelerated rotarod test (D), hanging wire test (E), and corner test, in which a lower corner index indicates better outcome (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for panel B or as median and range for panels C-F. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test for panel B and a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panels C-F. NS, nonsignificant.

ADAMTS13 deficiency worsens stroke outcomes with preceding RTI by S aureus. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Left: representative MRI images of brain (coronal) on day 2 after reperfusion. The white (demarked by yellow dots) indicates an infarct area. Right: infarct volume quantification (n = 11-13 mice per group). (C-F) Functional outcomes in the same groups of mice on weeks 1 and 4 after reperfusion (n = 10-11 mice per group). (C) mNSS in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). (D-F) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice as analyzed by motor strength in the accelerated rotarod test (D), hanging wire test (E), and corner test, in which a lower corner index indicates better outcome (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for panel B or as median and range for panels C-F. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test for panel B and a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panels C-F. NS, nonsignificant.

SARS-CoV-2 infection induces an imbalance VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, triggers systemic inflammatory response, and worsens stroke severity

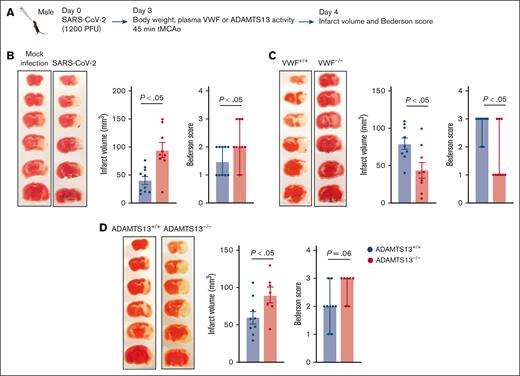

To determine a dose of SARS-CoV-2 capable of inducing a systemic inflammatory response in WT mice, animals were infected intranasally with sublethal doses of SARS-CoV-2 (300, 600, or 1200 PFUs per mouse) on day 0, and body weight was recorded daily up to day 10. Infection resulted in a transient, dose-dependent decrease in body weight, reaching its peak on days 3 to 5 of infection (supplemental Figure 4). Because no mortality was observed at any of the doses tested, the highest dose of SARS-CoV-2 (1200 PFUs per mouse) was selected for further experiments. To investigate the effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on stroke severity, WT mice were infected with SARS-CoV-2 on day 0 (Figure 5A). A progressive decrease in body weight confirmed infection, an increase in lung histological score (supplemental Figure 7B), and the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the lung, but not brain, specimens on day 3 (Figure 5B-C). SARS-CoV-2–infected WT mice exhibited increased plasma VWF levels and decreased plasma ADAMTS13 activity, resulting in a nearly fourfold increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (all P < .05 vs mock infection; Figure 5D). SARS-CoV-2–infected WT mice demonstrated increased plasma IL-6, CXCL1, and MCP-1 levels (all P < .05 vs mock infection), with no significant change in TNF-α levels (Figure 5E). In parallel experiments, SARS-CoV-2–infected WT mice were subjected to tMCAo on day 3 of infection, with infarct volumes and Bederson score assessed at 24 hours after reperfusion (Figure 6A). A significant increase in infarct volumes and Bederson scores were observed in SARS-CoV-2–infected WT mice (both P < .05 vs mock-infected WT), indicating a greater stroke severity and worse neurological outcome (Figure 6B). Long-term functional outcomes could not be evaluated because of animal protocol restrictions in the BSL-3 facility.

Preceding RTI caused by SARS-CoV-2 reduced body weight; imbalanced VWF-ADAMTS13 axis; and increased plasma IL-6, CXCL-1, and MCP-1. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Body weight changes in SARS-CoV-2– and mock-infected mice (n = 8 mice per group). (C) SARS-CoV-2 titer in the lungs and brain (n = 8 mice per group). (D) Plasma VWF levels (left), ADAMTS13 activity (middle), and VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (right) on day 3 after infection (n = 8 mice per group). (E) Plasma TNF-α (left), IL-6 (middle left), CXCL-1 (middle right) and MCP-1 (right) levels on day 3 after infection (n = 6-8 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panel B and an unpaired t test for panels C-E. NS, nonsignificant.

Preceding RTI caused by SARS-CoV-2 reduced body weight; imbalanced VWF-ADAMTS13 axis; and increased plasma IL-6, CXCL-1, and MCP-1. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Body weight changes in SARS-CoV-2– and mock-infected mice (n = 8 mice per group). (C) SARS-CoV-2 titer in the lungs and brain (n = 8 mice per group). (D) Plasma VWF levels (left), ADAMTS13 activity (middle), and VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio (right) on day 3 after infection (n = 8 mice per group). (E) Plasma TNF-α (left), IL-6 (middle left), CXCL-1 (middle right) and MCP-1 (right) levels on day 3 after infection (n = 6-8 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-way ANOVA followed by the Šidák post hoc test for panel B and an unpaired t test for panels C-E. NS, nonsignificant.

Preceding RTI caused by SARS-CoV-2 worsened stroke outcomes, alleviated by VWF deficiency and aggravated by ADAMTS13 deficiency. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B-D) Left: representative 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)-stained coronal brain sections after 45 minutes of ischemia followed by 23 hours of reperfusion (n = 7-10 mice per group). The white area indicates an infarct. Middle: infract volume quantification. Right: neurological Bederson score of the same mouse groups on day 1 after reperfusion (n = 7-10 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (middle) or median and range (right). Statistical analysis was performed with an unpaired t test for panels B-C (middle) or Mann-Whitney U test (right).

Preceding RTI caused by SARS-CoV-2 worsened stroke outcomes, alleviated by VWF deficiency and aggravated by ADAMTS13 deficiency. (A) Schematic of experimental design. (B-D) Left: representative 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)-stained coronal brain sections after 45 minutes of ischemia followed by 23 hours of reperfusion (n = 7-10 mice per group). The white area indicates an infarct. Middle: infract volume quantification. Right: neurological Bederson score of the same mouse groups on day 1 after reperfusion (n = 7-10 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (middle) or median and range (right). Statistical analysis was performed with an unpaired t test for panels B-C (middle) or Mann-Whitney U test (right).

To determine whether SARS-CoV-2 infection alone could affect the Bederson score, a separate subset of infected mice was evaluated on day 3 and day 4 of infection (mirroring assessments at 24 hours after reperfusion in mice subjected to tMCAo). No significant differences in Bederson score were observed between infected and mock-infected mice at these time points (supplemental Figure 5), indicating that SARS-CoV-2 infection did not independently affect the functional outcome in mice after experimental ischemic stroke and was predisposed to greater stroke severity.

VWF deficiency improves, whereas ADAMTS13 deficiency worsens, stroke outcome in mice with SARS-CoV-2 infection

To investigate the role of the VWF–ADAMTS13 axis in stroke severity in SARS-CoV-2–infected mice, the experiments were repeated with Vwf−/− and Adamts13−/− mice, along with respective controls. We found that SARS-CoV-2–infected Vwf−/− mice exhibited reduced infarct volumes and improved Bederson score (both P < .05 vs Vwf+/+; Figure 6C), whereas SARS-CoV-2–infected Adamts13−/− mice exhibited larger infarct volumes and worse Bederson scores (both P < .05 vs Adamts13+/+; Figure 6D). Additionally, SARS-CoV-2–infected Adamts13−/− mice demonstrated a more substantial body weight reduction than Adamts13+/+ controls (supplemental Figure 6), suggesting a more severe systemic response to infection.

Discussion

This study provides experimental evidence that RTIs preceding stroke exacerbate ischemic brain injury and worsen function outcomes by causing an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis. Specifically, we showed that sustained S aureus infection led to a 2.5-fold increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio, accompanied by larger infarct volumes and diminished long-term neurological function. This finding aligns with a previous study in which sustained Streptococcus pneumoniae infection was also associated with greater stroke severity.26 A single-dose S aureus infection produced only a mild imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, with a 1.5-fold increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio, which did not translate into greater stroke severity. These observations suggest that the severity of infection-induced stroke exacerbation depends on the extent of VWF-ADAMTS13 axis imbalance. These results were further supported by the observations with SARS-CoV-2 infection, in which even a single dose of the virus that produced a fourfold increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio significantly worsened stroke severity, as evidenced by larger infarct volumes and higher Bederson scores. Our findings are consistent with the observations in patients with COVID-19, in whom more severe infection was associated with a more significant imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis,27 higher incidence of ischemic stroke, and more complex stroke patterns, including multivascular distribution and frequent hemorrhagic transformations.28 Together, these results suggest that greater RTI severity leads to a more pronounced imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis and stroke severity.

The extent of VWF-ADAMTS13 axis imbalance appears to be linked to the extent of the systemic inflammatory response triggered by infection. In our study, single-dose S aureus infection did not alter proinflammatory cytokine levels. It produced only a mild increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio. At the same time, both sustained S aureus infection and SARS-CoV-2 infection led to a significant increase in plasma levels of IL-6, CXCL1, and MCP-1, and a more pronounced increase in the VWF:ADAMTS13 activity ratio. These findings suggest that a heightened systemic inflammatory response may drive the observed VWF-ADAMTS13 axis imbalance, contributing to worse stroke outcomes. Supporting this, studies have shown that a more pronounced systemic inflammatory response, indicated by higher plasma levels of C-reactive protein and proinflammatory cytokines, was associated with larger infarct sizes and worse neurological function.29-32 Mechanistically, it has been shown that cytokines released during inflammation may cause an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis by stimulating the release of ultralarge VWF molecules from endothelial cells, which can overwhelm the processing capacity of ADAMTS13, or by directly inhibiting the ADAMTS13 activity.33 This facilitates leukocyte adhesion to the vascular endothelium, further amplifying endothelial cell activation and promoting VWF release,34,35 establishing a positive feedback mechanism contributing to thromboinflammation.

To obtain direct evidence that an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis may contribute to RTI-induced exacerbation of ischemic stroke, we used Vwf−/− and Adamts13−/− mice. Our experiments showed that VWF deficiency significantly attenuated ischemic brain injury and improved functional outcomes in mice subjected to tMCAo with preceding sustained S aureus or SARS-CoV-2 infection. In contrast, the deficiency of ADAMTS13 produced the opposite effects, confirming that infection-induced axis imbalance represents the link between RTI and greater stroke severity. Prior research has shown that the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis promotes thromboinflammation in the ischemic brain through several mechanisms. Specifically, ADAMTS13 deficiency has been shown to accelerate blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, promote leakage of serum proteins into the peri-infarct cortex, and increase brain edema in mice after tMCAo.36 Another study has demonstrated that ADAMTS13 deficiency enhances neutrophil infiltration and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in ischemic brain tissue10 and increases the number of high mobility group box 1–expressing immune cells in the cortical penumbra.37 As an alarmin, high mobility group box 1 significantly promotes thromboinflammation and BBB damage.38 Furthermore, ADAMTS13 deficiency has been shown to restrict the formation of new blood vessels in the peri-infarct zone during the delayed stages of stroke, potentially contributing to worse long-term neurological outcomes.36 Conversely, VWF deficiency has been shown to protect the BBB, reduce infiltration of neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells in the ischemic brain, and facilitate revascularization after tMCAo.36,39 Importantly, infusion of recombinant ADAMTS13 in WT mice subjected to tMCAo reduced infarct volume and improved functional outcomes without producing cerebral hemorrhage.7 Similarly, anti-VWF antibody infusion preserved BBB integrity at the site of ischemic brain injury.36

Although the association between RTIs preceding stroke and greater stroke severity has been previously reported, our study is, to our knowledge, the first to provide direct experimental evidence of the existing pathogenetic link between the preceding RTIs and stroke severity. We demonstrated that an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis caused by RTI fosters a prothrombotic state, predisposing to exaggerated thromboinflammation in the brain after ischemic injury and contributing to worse stroke outcomes. By using two fundamentally different etiological agents, a bacterium (S aureus) and a virus (SARS-CoV-2), we showed that the axis imbalance represents a common host response to RTI, rather than a pathogen-specific phenomenon. This finding suggests that our results could be extrapolated to a broader spectrum of RTIs, enhancing their clinical relevance. Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of monitoring the balance between VWF and ADAMTS13 in individuals with RTI who are at risk of ischemic stroke, and suggests that targeting this axis could be a novel therapeutic strategy to prevent stroke or reduce its severity in this population.

Notably, neuroprotection in stroke has been a field that faced numerous unexpected failures. This lack of success has been attributed, in part, to the use of inadequate animal models of stroke relying only on healthy animals, focusing on infarct volumes measured 24 to 72 hours after stroke, and assessing short-term functional outcomes.40 In contrast, clinical studies prioritize long-term functional outcomes and account for the impact of preexisting comorbidities. In this manuscript, we address these limitations of preclinical studies by investigating the role of VWF-ADAMTS13 axis imbalance in the context of preexisting comorbidities (RTIs) and evaluating clinically relevant long-term functional outcomes. Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to perform tMCAo surgery within a biological safety cabinet in a biosafety level 3 facility. This innovative approach enabled us to investigate the effects of the highly pathogenic SARS-CoV-2 on stroke severity, establishing a foundation for future research exploring the impact of other high-risk pathogens on neurological outcomes.

Certain limitations of our study should also be acknowledged. Variability in infarct volumes between WT and Adamts13+/+ mice could be attributed to differences in sources from where they were obtained. WT mice were ordered from The Jackson Laboratory and likely have microbiota distinct from that of Adamts13+/+ mice that were derived by crossing Adamts13+/− mice in our animal facility. The differences in microbiota could affect the response to infection and stroke severity, resulting in variability between WT and Adamts13+/+. Another limitation involves VWF deficiency, which has been shown to abrogate the formation of Weibel-Palade bodies, endothelial-specific organelles storing VWF, and other molecules implicated in thromboinflammation.41-43 This endothelial dysfunction inherent to Vwf−/− mice complicates the interpretation of reduced stroke severity, because it may result from the absence of VWF itself and the loss of other essential constituents of Weibel-Palade bodies.

In conclusion, this study provides novel experimental evidence that an imbalance in the VWF-ADAMTS13 axis caused by RTI represents a pathogenetic mechanisms by which RTIs exacerbate ischemic stroke severity, with VWF playing a prothrombotic and proinflammatory role counteracted by the protective effects of ADAMTS13. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting VWF by recombinant ADAMTS13 as a strategy to mitigate the adverse effects of RTIs on stroke outcomes in addition to antimicrobial agents.

Acknowledgments

Staphylococcus aureus (USA300 strain) was a gift from C. Parlet (Iowa City VA Medical Center).

The A.K.C. laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R35HL139926) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant U01NS130587). J.M. is supported by a National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant (grant R35GM142936). R.B.P. is supported by the American Heart Association postdoctoral award (24POST1195275).

Authorship

Contribution: R.B.P. and A.K.C. were responsible for study conceptualization, experiment design, and manuscript writing; R.B.P. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the original manuscript; A.K.V., A.B.J., A.J., and S.S. performed the experiments; I.B. analyzed the data and cowrote the manuscript; J.M. provided von Willebrand factor substrate as well as the protocol for ADAMTS13 activity; P.G. and S.P. provided intellectual input and editing; A.K.C. conceived and supervised experiments, edited the manuscript, and secured funding for this study; and all authors reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rakesh B. Patel, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, 3160 Medical labs, Iowa City, IA 52242; email: rakeshkumar-patel@uiowa.edu; and Anil K. Chauhan, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, 3160 Medical labs, Iowa City, IA 52242; email: anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu.

References

Author notes

The data supporting this study's findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors, Rakesh B. Patel (rakeshkumar-patel@uiowa.edu) and Anil K. Chauhan (anil-chauhan@uiowa.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.