Key Points

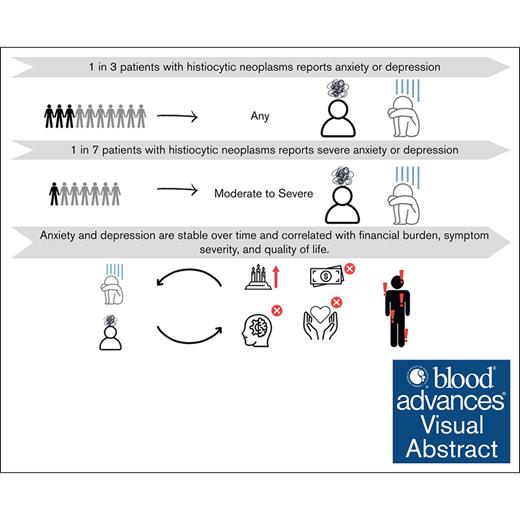

One in 3 patients with HNs report anxiety or depression, and 1 in 7 report moderate or severe anxiety or depression.

Anxiety and depression are stable over time and correlated with financial burden, symptom severity, and HRQoL.

Visual Abstract

Anxiety and depression are common in many cancers but, to our knowledge, have not been systematically studied in patients with histiocytic neoplasms (HNs). We sought to estimate rates of anxiety and depression and identify clinical features and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) associated with anxiety and depression in patients with HNs. A registry-based cohort of patients with HNs completing PROs including the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) from 2018 to 2023 was identified. Moderate or severe anxiety or depression were respectively defined as a score of ≥11 on the HADS anxiety or depression subscales. Associations of variables, including other validated PROs, with moderate or severe anxiety or depression were modeled with logistic regression to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. In 215 patients, ∼1 in 3 met the criteria for anxiety or depression, and 1 in 7 met the criteria for moderate or severe anxiety or depression. These estimates remained stable over a 12-month trajectory. Rates of depression, but not anxiety, significantly differed across HN types, with patients with Erdheim-Chester disease experiencing the highest rate. In addition, neurologic involvement, unemployment, and longer undiagnosed illness interval were significantly associated with increased risk of depression. Financial burden, financial worry, and severe disease-related symptoms were correlated with increased risk of both anxiety and depression. Conversely, increased general and cognitive health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were correlated with decreased risk of both anxiety and depression. In patients with HN, anxiety and depression are prevalent, stable over time, and correlated with financial burden, symptom severity, and HRQoL. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03329274.

Introduction

Anxiety is a multifaceted emotional state characterized by feelings of worry and can include physical and autonomic changes in reaction or anticipatory reaction to threats or stressors.1 Depression is a psychological state characterized by feelings of sadness and hopelessness, often accompanied by cognitive and physical symptoms. Across all cancer types, ∼1 in 10 patients report depression and 1 in 5 report anxiety.2 These rates remain relatively stable across the clinical trajectory and are similar to those in healthy adults without cancer.3-5 Anxiety and depression have also been associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer-specific mortality.6

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and non-Langerhans cell spectrum histiocytosis, comprising Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), xanthogranuloma-family disease, and histiocytic sarcoma, are rare hematologic diseases, with the most common (LCH) affecting only 1 to 2 cases per million adults.7-10 In our pilot study of patient-reported symptoms in 50 patients with ECD, half of participants endorsed sadness and half endorsed stress or anxiety as symptoms.11 Additionally, generalized inflammatory symptoms that can also present as manifestations of anxiety and depression are well-recognized in ECD, LCH, and RDD.12-19 To date, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic or dedicated investigation of anxiety or depression in patients with histiocytic neoplasms (HNs) and their associated disease factors or psychosocial end points.

In the current study, we implemented the validated hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) to characterize anxiety and depression over time in a cohort of 215 patients with HNs enrolled in a prospective registry study capturing patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Furthermore, we investigated associations of anxiety and depression with histiocytosis features, treatment, and validated PROs assessing financial burden, cognitive function, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Methods

This is an institutional review board–approved registry-based cohort study maintained at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: #NCT03329274). Participants providing informed consent and enrolling from 2018 to 2023 with completed HADS assessment at enrollment were included. Registry participants completed PROs at the time of enrollment, 6 months, and 12 months. The 14-item HADS inventory was used to assess anxiety and depression (7 items for each subscale). Each item was rated 0 to 3, with a range for each subscale of 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating increased anxiety or depression. Subscale cutoff scores of 8 to 10, 11 to 14, and 15 to 21 were used to indicate mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, respectively.20

Demographics including sex and age, disease features including HN type, length of undiagnosed histiocytosis (from first symptom to diagnosis), and length of diagnosed histiocytosis (from diagnosis to last follow-up) were ascertained from the registry. In addition to the HADS, 6 other PROs were ascertained: (1) financial burden and worry21; (2) functional assessment of cancer therapy, general (FACT-G)22; (3) functional assessment of cancer therapy, cognition (FACT-Cog)23,24; (4) a histiocytosis symptom inventory initially content validated in ECD (ECD-SS)11; (5) brief fatigue inventory25; and (6) brief pain inventory (BPI).26 Based on a published composite measure of financial burden in patients with colorectal cancer, 8 binary questions assessing effects of histiocytosis and treatment on financial burden were posed and scored (range, 0-8) and 1 question assessing financial worry was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale.21 Higher scores reflect more financial burden and financial worry. The FACT-G is a validated PRO of HRQoL with subscale scores for physical, functional, social, and emotional well-being.22 Higher scores indicate better self-reported HRQoL. The FACT-Cog, similar in design to the FACT-G, assesses perceived cognitive function on HRQoL, with subscale scores for perceived cognitive impairments, perceived cognitive abilities, impact of perceived cognitive impairments on HRQoL, and comments from others on cognitive function.23,24 Higher scores indicate better self-reported cognitive functioning. The ECD-SS is a symptom inventory in which patients rate the frequency and severity of their top 3 and 5 disease-related symptoms (eg, headache, cough, pain, and fever).11 Frequency categories are: never, rarely, occasionally, frequently, and almost constantly. Symptom severity is rated on a numeric scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse symptom severity. Additionally, the ECD-SS ascertains a checklist of specific symptoms in the following categories: neurologic, gastrological, pain, vision, and respiratory. The brief fatigue inventory contains 9 items, each rated on a numeric scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse fatigue.25 Similarly, the BPI contains 11 items each rated on a numeric scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse pain.26

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the cohort and depression and anxiety at study enrollment and at a 12-month follow-up interval. The 6-month assessment was not analyzed because the rates of HADS anxiety and depression were relatively stable through 12 months of follow-up. Rates of patient-reported anxiety and depression were compared across disease groups (ECD, LCH, and RDD) with χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Univariable associations of variables with moderate or severe anxiety or depression at baseline were modeled with logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were 2-sided with a statistical level of significance of <.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

There were 215 patients with HNs who enrolled in the registry and completed the HADS assessment at enrollment (Table 1). Of these patients, 123 also completed the HADS at 12 months. Median age at enrollment was 54.7 years, and the top 3 HNs were ECD (64%), LCH (14%), and RDD (9%). Fifteen patients (7%) had mixed ECD/LCH, and 4 (2%) had mixed ECD/RDD. A total of 84 (39%) patients were not on treatment at enrollment, and this lowered to 22% (n = 27 [of 123 assessed]) 12 months later at the final HADS assessment. Unemployment remained relatively stable, with 42 (20%) unemployed at enrollment and 29 of 123 assessed (24%) unemployed 12 months later. The average time from first symptom to HN diagnosis was 2.2 years.

Distribution of cohort characteristics

| Variable . | Category . | Overall cohort . | ECD cohort . | LCH cohort . | RDD cohort . | Cohort with other HNs . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | ||

| Age at histiocytosis diagnosis | Years | 215 | 100 | 51.2 (0.4-76.9) | 138 | 100 | 53.6 (8.1-76.9) | 30 | 100 | 37.3 (0.4-61.6) | 19 | 100 | 46 (23.3-69.8) | 28 | 100 | 44.8 (20-69.2) |

| Age at registry enrollment | Years | 215 | 100 | 54.7 (18.9-80) | 138 | 100 | 56.6 (18.9-80.0) | 30 | 100 | 45.8 (24.4-66.8) | 19 | 100 | 48.5 (23.5-71.2) | 28 | 100 | 50.5 (22.7-74.3) |

| Diagnosis | ECD | 138 | 64 | 138 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| LCH | 30 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| RDD | 19 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Xanthogranuloma-family | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Histiocytic sarcoma | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Mixed ECD/LCH | 15 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 54 | ||||||

| Mixed ECD/RDD | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Other | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 99 | 46 | 57 | 41 | 19 | 63 | 12 | 63 | 11 | 39 | |||||

| Male | 116 | 54 | 81 | 59 | 11 | 37 | 7 | 37 | 17 | 61 | ||||||

| Length of undiagnosed illness | Years | 215 | 100 | 0.68 (0-20.6) | 138 | 100 | 0.8 (0-20.6) | 30 | 100 | 0.4 (0-10.3) | 19 | 100 | 0.6 (0.02-17.6) | 28 | 100 | 0.5 (0-9.7) |

| Length of diagnosed illness | Years | 215 | 100 | 4.9 (0.08-42.3) | 138 | 100 | 5.1 (0.2-38.8) | 30 | 100 | 6.6 (0.2-42.3) | 19 | 100 | 2.8 (0.2-18.3) | 28 | 100 | 4.3 (0.08-29.2) |

| Sites of disease | Bone | 175 | 81 | 126 | 91 | 19 | 63 | 8 | 42 | 22 | 79 | |||||

| Neurologic | 129 | 60 | 95 | 69 | 13 | 43 | 5 | 26 | 16 | 57 | ||||||

| Brain/parenchyma | 95 | 44 | 78 | 57 | 11 | 37 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 18 | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 73 | 34 | 66 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 38 | 18 | 27 | 20 | 8 | 27 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | ||||||

| Retroperitoneum | 84 | 39 | 74 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 21 | 6 | 21 | ||||||

| Abdomen | 37 | 17 | 22 | 16 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 32 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Skin | 59 | 17 | 28 | 20 | 9 | 30 | 8 | 42 | 14 | 50 | ||||||

| Lymph node | 27 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 17 | 9 | 47 | 2 | 7 | ||||||

| Other | 36 | 17 | 18 | 13 | 5 | 17 | 6 | 32 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 92 | 43 | 68 | 49 | 24 | 80 | 9 | 47 | 20 | 71 | |||||

| Diabetes | 40 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 27 | 90 | 8 | 42 | 21 | 75 | ||||||

| Has a caregiver | No | 128 | 60 | 75 | 54 | 25 | 83 | 14 | 50 | 14 | 74 | |||||

| Yes | 87 | 40 | 63 | 46 | 5 | 17 | 14 | 50 | 5 | 26 | ||||||

| Employment at enrollment | Full-time | 91 | 42 | 47 | 34 | 16 | 53 | 12 | 63 | 16 | 57 | |||||

| Part-time | 27 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 16 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 42 | 20 | 32 | 23 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Retired | 53 | 25 | 44 | 32 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Employment at 12 mo (n = 123) | Full-time | 37 | 30 | 30 | 27 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 | 58 | |||||

| Part-time | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 29 | 24 | 26 | 23 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | 25 | ||||||

| Retired | 46 | 37 | 45 | 41 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Treatment at enrollment | None | 84 | 39 | 43 | 31 | 20 | 67 | 9 | 47 | 12 | 43 | |||||

| Conventional | 17 | 8 | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Targeted | 113 | 53 | 82 | 59 | 10 | 33 | 10 | 53 | 11 | 39 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Treatment at 12 mo (n = 123) | None | 27 | 22 | 24 | 22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | 25 | |||||

| Conventional | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| Targeted | 78 | 63 | 72 | 65 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 | 50 | ||||||

| Other∗ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Unknown | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 17 | ||||||

| Variable . | Category . | Overall cohort . | ECD cohort . | LCH cohort . | RDD cohort . | Cohort with other HNs . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | n . | % . | Median (range) . | ||

| Age at histiocytosis diagnosis | Years | 215 | 100 | 51.2 (0.4-76.9) | 138 | 100 | 53.6 (8.1-76.9) | 30 | 100 | 37.3 (0.4-61.6) | 19 | 100 | 46 (23.3-69.8) | 28 | 100 | 44.8 (20-69.2) |

| Age at registry enrollment | Years | 215 | 100 | 54.7 (18.9-80) | 138 | 100 | 56.6 (18.9-80.0) | 30 | 100 | 45.8 (24.4-66.8) | 19 | 100 | 48.5 (23.5-71.2) | 28 | 100 | 50.5 (22.7-74.3) |

| Diagnosis | ECD | 138 | 64 | 138 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| LCH | 30 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| RDD | 19 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Xanthogranuloma-family | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Histiocytic sarcoma | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Mixed ECD/LCH | 15 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 54 | ||||||

| Mixed ECD/RDD | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Other | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 99 | 46 | 57 | 41 | 19 | 63 | 12 | 63 | 11 | 39 | |||||

| Male | 116 | 54 | 81 | 59 | 11 | 37 | 7 | 37 | 17 | 61 | ||||||

| Length of undiagnosed illness | Years | 215 | 100 | 0.68 (0-20.6) | 138 | 100 | 0.8 (0-20.6) | 30 | 100 | 0.4 (0-10.3) | 19 | 100 | 0.6 (0.02-17.6) | 28 | 100 | 0.5 (0-9.7) |

| Length of diagnosed illness | Years | 215 | 100 | 4.9 (0.08-42.3) | 138 | 100 | 5.1 (0.2-38.8) | 30 | 100 | 6.6 (0.2-42.3) | 19 | 100 | 2.8 (0.2-18.3) | 28 | 100 | 4.3 (0.08-29.2) |

| Sites of disease | Bone | 175 | 81 | 126 | 91 | 19 | 63 | 8 | 42 | 22 | 79 | |||||

| Neurologic | 129 | 60 | 95 | 69 | 13 | 43 | 5 | 26 | 16 | 57 | ||||||

| Brain/parenchyma | 95 | 44 | 78 | 57 | 11 | 37 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 18 | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 73 | 34 | 66 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Pulmonary | 38 | 18 | 27 | 20 | 8 | 27 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | ||||||

| Retroperitoneum | 84 | 39 | 74 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 21 | 6 | 21 | ||||||

| Abdomen | 37 | 17 | 22 | 16 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 32 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Skin | 59 | 17 | 28 | 20 | 9 | 30 | 8 | 42 | 14 | 50 | ||||||

| Lymph node | 27 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 17 | 9 | 47 | 2 | 7 | ||||||

| Other | 36 | 17 | 18 | 13 | 5 | 17 | 6 | 32 | 7 | 25 | ||||||

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 92 | 43 | 68 | 49 | 24 | 80 | 9 | 47 | 20 | 71 | |||||

| Diabetes | 40 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 27 | 90 | 8 | 42 | 21 | 75 | ||||||

| Has a caregiver | No | 128 | 60 | 75 | 54 | 25 | 83 | 14 | 50 | 14 | 74 | |||||

| Yes | 87 | 40 | 63 | 46 | 5 | 17 | 14 | 50 | 5 | 26 | ||||||

| Employment at enrollment | Full-time | 91 | 42 | 47 | 34 | 16 | 53 | 12 | 63 | 16 | 57 | |||||

| Part-time | 27 | 13 | 14 | 10 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 16 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 42 | 20 | 32 | 23 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Retired | 53 | 25 | 44 | 32 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Employment at 12 mo (n = 123) | Full-time | 37 | 30 | 30 | 27 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 | 58 | |||||

| Part-time | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 29 | 24 | 26 | 23 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | 25 | ||||||

| Retired | 46 | 37 | 45 | 41 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Treatment at enrollment | None | 84 | 39 | 43 | 31 | 20 | 67 | 9 | 47 | 12 | 43 | |||||

| Conventional | 17 | 8 | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 14 | ||||||

| Targeted | 113 | 53 | 82 | 59 | 10 | 33 | 10 | 53 | 11 | 39 | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Treatment at 12 mo (n = 123) | None | 27 | 22 | 24 | 22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | 25 | |||||

| Conventional | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | ||||||

| Targeted | 78 | 63 | 72 | 65 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 | 50 | ||||||

| Other∗ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Unknown | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 17 | ||||||

N/A, not applicable.

Pembrolizumab, imatinib.

At enrollment, 74 (34%) and 60 (28%) patients met HADS criteria for clinical anxiety or depression, respectively (Figure 1; supplemental Table 1). Twenty-eight (13%) patients met criteria for moderate or severe anxiety and 32 (15%) met criteria for moderate or severe depression. Rates of anxiety or moderate-to-severe anxiety did not differ across the disease types of ECD, LCH, or RDD, with 47 (34%) patients with ECD, 13 (43%) patients with LCH, and 4 (21%) patients with RDD meeting criteria for anxiety (P = .28), and with 17 (12%) patients with ECD, 5 (17%) patients with LCH, and 3 (16%) patients with RDD meeting criteria for moderate or severe anxiety (P = .72). However, rates of depression or moderate-to-severe depression did differ across disease types, with 46 (33%) patients with ECD, 3 (10%) patients with LCH, and 4 (21%) patients with RDD meeting criteria for depression (P = .03), and 27 (20%) patients with ECD, 2 (7%) patients with LCH, and no patients with RDD meeting criteria for moderate-to-severe depression (P = .02).

The distribution of the HADS categories for anxiety and depression at enrollment, 12 months, and the changes from enrollment to 12 months. (A) Anxiety categories as determined by the HADS at enrollment. (B) Depression categories as determined by the HADS at enrollment. (C) Anxiety categories as determined by the HADS at 12 months. (D) Depression categories as determined by the HADS at 12 months. (E) Change in anxiety categories as determined by the HADS from enrollment to 12 months. (F) Change in depression categories as determined by the HADS from enrollment to 12 months.

The distribution of the HADS categories for anxiety and depression at enrollment, 12 months, and the changes from enrollment to 12 months. (A) Anxiety categories as determined by the HADS at enrollment. (B) Depression categories as determined by the HADS at enrollment. (C) Anxiety categories as determined by the HADS at 12 months. (D) Depression categories as determined by the HADS at 12 months. (E) Change in anxiety categories as determined by the HADS from enrollment to 12 months. (F) Change in depression categories as determined by the HADS from enrollment to 12 months.

At 12 months follow-up, 123 patients completed the HADS, and 28 (23%) and 41 (33%) met criteria for anxiety or depression, respectively. Sixteen (13%) met criteria for moderate or severe anxiety, and 17 (14%) met criteria for moderate or severe depression. Most patients did not change severity categories of depression (n = 107, 87%) or anxiety (n = 109, 89%) over time (Figure 1; supplemental Table 1).

Older patients were less likely to meet criteria for moderate or severe anxiety such that with each year increase in age there was a 3% decrease in likelihood of meeting criteria for moderate or severe anxiety (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-1.00; P = .04; Table 2). There was no association between treatment at enrollment or 12 months with anxiety at enrollment or 12 months, respectively. Patients with a graduate or postgraduate degree were 68% less likely to report moderate or severe anxiety (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.12-0.84; P = .02). Patients with increased financial burden (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45; P = .04) or worry (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.33-2.47; P = .0002) were more likely to meet criteria for moderate or severe anxiety. Patients with better cognitive HRQoL or with better general HRQoL were less likely to report moderate or severe anxiety; for example, for each 1-point increase on the FACT-Cog assessment for perceived cognitive impairments on QoL subscale, there was a 13% decrease in likelihood of meeting criteria for moderate or severe anxiety (eg, OR for FACT-Cog perceived cognitive impairments on QoL, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76-0.96; P = .006; and OR for FACT-G total, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.91-0.96; P < .0001). Patients with at least 1 gastrological symptom were more likely to report moderate or severe anxiety (OR, 2.88, 95%CI, 1.05-7.91; P = .04). Whereas patients with at least 1 pain symptom were not more likely to report moderate or severe anxiety, severity of pain was associated with moderate or severe anxiety (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.05-1.40; P = .0095). Similarly, severity of fatigue was associated with moderate or severe anxiety (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.10-1.46; P = .001). Finally, in general, patients with more severe symptoms were more likely to report moderate or severe anxiety (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.18-1.96; P = .001).

Associations with moderate or severe anxiety at enrollment

| Variable . | Category . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Ref | ||

| Female | 1.42 | 0.64-3.14 | .39 | |

| Age at histiocytosis diagnosis | Continuous, y | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | .12 |

| Age at enrollment | Continuous, y | 0.97 | 0.94-1.00 | .04 |

| Diagnosis | Non-ECD | Ref | ||

| ECD or mixed ECD | 0.75 | 0.32-1.77 | .51 | |

| Neurologic involvement | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.77 | 0.34-1.74 | .52 | |

| Driver mutation | None or other | Ref | ||

| BRAFV600E | 0.99 | 0.41-2.43 | .99 | |

| RAS isoform only | 1.80 | 0.43-7.50 | .42 | |

| MAP2K1 only | 1.35 | 0.33-5.47 | .67 | |

| Length of undiagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 0.99 | 0.88-1.12 | .86 |

| Length of diagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 0.97 | 0.91-1.04 | .42 |

| Treatment at enrollment | None | Ref | ||

| Conventional | 2.56 | 0.69-9.57 | .16 | |

| Targeted | 1.28 | 0.53-3.07 | .59 | |

| Best response at enrollment | PR/CR | Ref | ||

| SD/PD | 1.03 | 0.24-4.48 | .96 | |

| Education | High school or some high school | Ref | ||

| Undergraduate | 0.43 | 0.15-1.19 | .10 | |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 0.32 | 0.12-0.84 | .02 | |

| Employment at enrollment | Full-time | Ref | ||

| Part-time | 0.75 | 0.20-2.85 | .67 | |

| Unemployed | 1.41 | 0.54-3.72 | .49 | |

| Retired | 0.49 | 0.15-1.59 | .23 | |

| Financial burden scale | Continuous | 1.21 | 1.01-1.45 | .04 |

| Financial worry scale | Continuous | 1.81 | 1.33-2.47 | .0002 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments scale | Continuous | 0.98 | 0.96-1.00 | .10 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments on QoL scale | Continuous | 0.87 | 0.81-0.94 | .0004 |

| FACT-Cog: comments from others scale | Continuous | 0.85 | 0.76-0.96 | .006 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive abilities scale | Continuous | 0.96 | 0.91-1.01 | .12 |

| FACT-G: physical well-being scale | Continuous | 0.91 | 0.86-0.97 | .002 |

| FACT-G: emotional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.69 | 0.61-0.79 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: social well-being scale | Continuous | 0.88 | 0.82-0.93 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: functional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.86 | 0.80-0.92 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: total | Continuous | 0.93 | 0.91-0.96 | <.0001 |

| BFI: total | Continuous | 1.27 | 1.10-1.46 | .001 |

| BPI: total | Continuous | 1.21 | 1.05-1.40 | .0095 |

| ECD-SS: neurologic symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | Not | Estimable∗ | ||

| ECD-SS: gastrological symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.88 | 1.05-7.91 | .04 | |

| ECD-SS: pain symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.51 | 0.65-3.52 | .34 | |

| ECD-SS: vision symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.33 | 0.58-3.07 | .50 | |

| ECD-SS: respiratory symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.19 | 0.98-4.92 | .06 | |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.34 | 1.07-1.68 | .01 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.52 | 1.18-1.96 | .001 |

| Variable . | Category . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Ref | ||

| Female | 1.42 | 0.64-3.14 | .39 | |

| Age at histiocytosis diagnosis | Continuous, y | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | .12 |

| Age at enrollment | Continuous, y | 0.97 | 0.94-1.00 | .04 |

| Diagnosis | Non-ECD | Ref | ||

| ECD or mixed ECD | 0.75 | 0.32-1.77 | .51 | |

| Neurologic involvement | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.77 | 0.34-1.74 | .52 | |

| Driver mutation | None or other | Ref | ||

| BRAFV600E | 0.99 | 0.41-2.43 | .99 | |

| RAS isoform only | 1.80 | 0.43-7.50 | .42 | |

| MAP2K1 only | 1.35 | 0.33-5.47 | .67 | |

| Length of undiagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 0.99 | 0.88-1.12 | .86 |

| Length of diagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 0.97 | 0.91-1.04 | .42 |

| Treatment at enrollment | None | Ref | ||

| Conventional | 2.56 | 0.69-9.57 | .16 | |

| Targeted | 1.28 | 0.53-3.07 | .59 | |

| Best response at enrollment | PR/CR | Ref | ||

| SD/PD | 1.03 | 0.24-4.48 | .96 | |

| Education | High school or some high school | Ref | ||

| Undergraduate | 0.43 | 0.15-1.19 | .10 | |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 0.32 | 0.12-0.84 | .02 | |

| Employment at enrollment | Full-time | Ref | ||

| Part-time | 0.75 | 0.20-2.85 | .67 | |

| Unemployed | 1.41 | 0.54-3.72 | .49 | |

| Retired | 0.49 | 0.15-1.59 | .23 | |

| Financial burden scale | Continuous | 1.21 | 1.01-1.45 | .04 |

| Financial worry scale | Continuous | 1.81 | 1.33-2.47 | .0002 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments scale | Continuous | 0.98 | 0.96-1.00 | .10 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments on QoL scale | Continuous | 0.87 | 0.81-0.94 | .0004 |

| FACT-Cog: comments from others scale | Continuous | 0.85 | 0.76-0.96 | .006 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive abilities scale | Continuous | 0.96 | 0.91-1.01 | .12 |

| FACT-G: physical well-being scale | Continuous | 0.91 | 0.86-0.97 | .002 |

| FACT-G: emotional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.69 | 0.61-0.79 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: social well-being scale | Continuous | 0.88 | 0.82-0.93 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: functional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.86 | 0.80-0.92 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: total | Continuous | 0.93 | 0.91-0.96 | <.0001 |

| BFI: total | Continuous | 1.27 | 1.10-1.46 | .001 |

| BPI: total | Continuous | 1.21 | 1.05-1.40 | .0095 |

| ECD-SS: neurologic symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | Not | Estimable∗ | ||

| ECD-SS: gastrological symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.88 | 1.05-7.91 | .04 | |

| ECD-SS: pain symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.51 | 0.65-3.52 | .34 | |

| ECD-SS: vision symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.33 | 0.58-3.07 | .50 | |

| ECD-SS: respiratory symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.19 | 0.98-4.92 | .06 | |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.34 | 1.07-1.68 | .01 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.52 | 1.18-1.96 | .001 |

BFI, brief fatigue inventory; CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; Ref, reference; SD, stable disease.

All the patients who reported no neurologic symptoms also reported no anxiety.

Patients with an ECD diagnosis were 4-times more likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 4.15; 95% CI, 1.21-14.21; P = .02) and patients with neurologic involvement were more than twice as likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.06-6.27; P = .04; Table 3). Patients who were on conventional treatment at enrollment were almost 4-times more likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 1.11-14.13; P = .03) compared with patients who were not on treatment at enrollment. However, this association did not persist 12 months later. Patients who were retired were >4 times as likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 4.45; 95% CI, 1.30-15.26; P = .02) compared with patients employed full-time. Patients who were unemployed were more than 13 times as likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 13.38; 95% CI, 4.11-43.56; P < .0001) compared with full-time employed counterparts. A longer length of undiagnosed histiocytosis was associated with a higher likelihood of moderate or severe depression (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.26; P = .004). Patients with increased financial burden (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.02-1.44; P = .03) or worry (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.36-2.48; P < .0001) were more likely to report moderate or severe depression. Patients with better cognitive HRQoL or with better general HRQoL were less likely to report moderate or severe depression; for example, for each 1-point increase on the FACT-G assessment total score for HRQoL, there was a 12% decrease in likelihood of meeting criteria for moderate or severe depression (eg, OR for FACT-Cog perceived cognitive impairments on HRQoL: 0.74; 95% CI, 0.67-0.81; P < .0001, and OR for FACT-G total: 0.88; 95% CI, 0.85-0.92; P < .0001). Patients with at least 1 gastrological symptom, or 1 vision symptom, or 1 respiratory symptom were more likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 6.56; 95% CI, 1.93-22.34; P = .003; OR, 4.35; 95% CI, 1.99-9.50; P = .0002; and OR, 2.66; 95% CI, 1.24-5.72; P = .01, respectively). Although patients with at least 1 pain symptom were not more likely to report moderate or severe depression, severity of pain was associated with moderate or severe depression (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.44; P = .001). Similarly, severity of fatigue was associated with moderate or severe depression (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.38-1.99; P < .0001). Finally, in general, patients with more severe symptoms were more likely to report moderate or severe depression (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.41-2.43; P < .0001).

Associations with moderate or severe depression at enrollment

| Variable . | Category . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Ref | ||

| Female | 0.77 | 0.36-1.66 | .51 | |

| Age at histiocytosis diagnosis | Continuous, y | 1.00 | 0.97-1.02 | .71 |

| Age at enrollment | Continuous, y | 0.99 | 0.96-1.02 | .41 |

| Diagnosis | Non-ECD | Ref | ||

| ECD or mixed ECD | 4.15 | 1.21-14.21 | .02 | |

| Neurologic involvement | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.58 | 1.06-6.27 | .04 | |

| Driver mutation | None or other | Ref | ||

| BRAFV600E | 0.87 | 0.39-1.92 | .73 | |

| RAS isoform only | 0.75 | 0.15-3.69 | .72 | |

| MAP2K1 only | 0.27 | 0.03-2.19 | .22 | |

| Length of undiagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 1.15 | 1.04-1.26 | .004 |

| Length of diagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 1.02 | 0.97-1.08 | .43 |

| Treatment at enrollment | None | Ref | ||

| Conventional | 3.96 | 1.11-14.13 | .03 | |

| Targeted | 1.92 | 0.80-4.63 | .15 | |

| Best response at enrollment | PR/CR | Ref | ||

| SD/PD | 1.67 | 0.26-10.82 | .59 | |

| Education | High school or some high school | Ref | ||

| Undergraduate | 0.77 | 0.26-2.25 | .63 | |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 0.85 | 0.32-2.26 | .75 | |

| Employment at enrollment | Full-time | Ref | ||

| Part-time | 2.72 | 0.57-12.99 | .21 | |

| Unemployed | 13.38 | 4.11-43.56 | <.0001 | |

| Retired | 4.45 | 1.30-15.26 | .02 | |

| Financial burden scale | Continuous | 1.22 | 1.02-1.44 | .03 |

| Financial worry scale | Continuous | 1.84 | 1.36-2.48 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments scale | Continuous | 0.94 | 0.92-0.97 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments on qol scale | Continuous | 0.74 | 0.67-0.81 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: comments from others scale | Continuous | 0.75 | 0.66-0.84 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive abilities scale | Continuous | 0.91 | 0.87-0.96 | .0002 |

| FACT-G: physical well-being scale | Continuous | 0.83 | 0.77-0.89 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: emotional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.76 | 0.68-0.84 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: social well-being scale | Continuous | 0.83 | 0.78-0.89 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: functional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.73 | 0.66-0.81 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: total | Continuous | 0.88 | 0.85-0.92 | <.0001 |

| BFI: total | Continuous | 1.66 | 1.38-1.99 | <.0001 |

| BPI: total | Continuous | 1.25 | 1.09-1.44 | .001 |

| ECD-SS: neurologic symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | Not | Estimable∗ | ||

| ECD-SS: gastrological symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 6.56 | 1.93-22.34 | .003 | |

| ECD-SS: pain symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.60 | 0.72-3.57 | .25 | |

| ECD-SS: vision symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 4.35 | 1.99-9.50 | .0002 | |

| ECD-SS: respiratory symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.66 | 1.24-5.72 | .01 | |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.81 | 1.38-2.37 | <.0001 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.85 | 1.41-2.43 | <.0001 |

| Variable . | Category . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Ref | ||

| Female | 0.77 | 0.36-1.66 | .51 | |

| Age at histiocytosis diagnosis | Continuous, y | 1.00 | 0.97-1.02 | .71 |

| Age at enrollment | Continuous, y | 0.99 | 0.96-1.02 | .41 |

| Diagnosis | Non-ECD | Ref | ||

| ECD or mixed ECD | 4.15 | 1.21-14.21 | .02 | |

| Neurologic involvement | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.58 | 1.06-6.27 | .04 | |

| Driver mutation | None or other | Ref | ||

| BRAFV600E | 0.87 | 0.39-1.92 | .73 | |

| RAS isoform only | 0.75 | 0.15-3.69 | .72 | |

| MAP2K1 only | 0.27 | 0.03-2.19 | .22 | |

| Length of undiagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 1.15 | 1.04-1.26 | .004 |

| Length of diagnosed illness | Continuous, y | 1.02 | 0.97-1.08 | .43 |

| Treatment at enrollment | None | Ref | ||

| Conventional | 3.96 | 1.11-14.13 | .03 | |

| Targeted | 1.92 | 0.80-4.63 | .15 | |

| Best response at enrollment | PR/CR | Ref | ||

| SD/PD | 1.67 | 0.26-10.82 | .59 | |

| Education | High school or some high school | Ref | ||

| Undergraduate | 0.77 | 0.26-2.25 | .63 | |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 0.85 | 0.32-2.26 | .75 | |

| Employment at enrollment | Full-time | Ref | ||

| Part-time | 2.72 | 0.57-12.99 | .21 | |

| Unemployed | 13.38 | 4.11-43.56 | <.0001 | |

| Retired | 4.45 | 1.30-15.26 | .02 | |

| Financial burden scale | Continuous | 1.22 | 1.02-1.44 | .03 |

| Financial worry scale | Continuous | 1.84 | 1.36-2.48 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments scale | Continuous | 0.94 | 0.92-0.97 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive impairments on qol scale | Continuous | 0.74 | 0.67-0.81 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: comments from others scale | Continuous | 0.75 | 0.66-0.84 | <.0001 |

| FACT-Cog: perceived cognitive abilities scale | Continuous | 0.91 | 0.87-0.96 | .0002 |

| FACT-G: physical well-being scale | Continuous | 0.83 | 0.77-0.89 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: emotional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.76 | 0.68-0.84 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: social well-being scale | Continuous | 0.83 | 0.78-0.89 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: functional well-being scale | Continuous | 0.73 | 0.66-0.81 | <.0001 |

| FACT-G: total | Continuous | 0.88 | 0.85-0.92 | <.0001 |

| BFI: total | Continuous | 1.66 | 1.38-1.99 | <.0001 |

| BPI: total | Continuous | 1.25 | 1.09-1.44 | .001 |

| ECD-SS: neurologic symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | Not | Estimable∗ | ||

| ECD-SS: gastrological symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 6.56 | 1.93-22.34 | .003 | |

| ECD-SS: pain symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.60 | 0.72-3.57 | .25 | |

| ECD-SS: vision symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 4.35 | 1.99-9.50 | .0002 | |

| ECD-SS: respiratory symptom | No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.66 | 1.24-5.72 | .01 | |

| Top 3 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.81 | 1.38-2.37 | <.0001 |

| Top 5 ECD-SS symptoms: severity | Continuous | 1.85 | 1.41-2.43 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations are explained in Table 2.

All but 3 patients who reported no neurologic symptoms also reported no depression.

Discussion

We provide, to our knowledge, the first systematic study of clinical anxiety and depression in patients with HNs. Approximately 1 in 3 patients with HNs met criteria for anxiety or depression, and 1 in 7 demonstrated moderate or severe anxiety or depression. These estimates remained stable over a clinical trajectory of 12 months. Compared with patients with cancer, ∼10% of whom experience anxiety and 15% experience depression, patients with HNs experience higher anxiety and depression by more than twofold.27 Compared with patients with other rare cancers, 20% of whom experience anxiety and 17% experience depression, patients with HNs experienced elevated anxiety and depression as well.28

We identified several variables that were associated with moderate or severe anxiety and depression. In general, financial burden and financial worry as well as severe disease-related symptoms were correlated with an increased risk of anxiety and depression. Conversely, better general HRQoL and cognitive HRQoL were correlated with a decreased risk of anxiety and depression. Financial burden has previously been associated with psychological well-being in patients with common cancers.29,30 In patients with breast, prostate, or lung cancer, financial burden was associated with depression and anxiety, with more pronounced associations when depression and anxiety were severe.29 In a study of survivors of hematologic cancers, Hall et al reported that the majority of the top 10 most frequently endorsed high or very high unmet needs were related to emotional health.31 Furthermore, severe depression and anxiety along with elevated financial burden were consistently associated with the top 3 high or very high unmet needs reported by survivors of hematologic cancer. We would hypothesize that financial burden may be particularly salient for ECD and other HNs, for which patients endure prolonged diagnostic delay, numerous medical consultations, extensive and repeated diagnostic procedures, and often costs incurred for travel for specialty care. Furthermore, we found patients who were retired or unemployed, for whom financial burden may be most relevant, were significantly more likely to report moderate or severe depression compared with counterparts who were fully employed. In addition to the financial ramifications of unemployment, there is evidence that joblessness can lead to depression by way of loss of sense of identity and self-esteem.32 These associations provide opportunity for intervention to mitigate depression associated with unemployment, as research has demonstrated that resilient coping in the setting of unemployment is associated with fewer depressive symptoms33; psychosocial support to boost coping related to unemployment may mitigate depression in our patients.

In this study, we found a strong association between the severity of histiocytosis symptoms and both anxiety and depression. Previously we showed that ∼60% of patients with ECD report clinically relevant pain (defined as having at least 1 BPI item scored ≥4).34 Another observational study on cancer pain, anxiety, and depression demonstrated a strong association between the presence and severity of pain with anxiety and depression.35 There are several possible interpretations of the association between symptom burden and anxiety and depression. First, at face value, unmanaged physical symptoms can understandably lead to psychological distress. Furthermore, poorly managed symptoms and related functional impairments can impede daily functioning, social interactions, and ability to enjoy life, all of which can contribute to worry and sadness. On a biologic level, both ECD and LCH are associated with florid immune and cytokine disturbances, which could lead to neurobiological manifestations of immune dysregulation, including dysphoria, depression, or anxiety.36-39 Histiocytic disorders are associated with various endocrinopathies, such as hypogonadism and hypothyroidism, which may contribute to mood disturbances.12,40,41 The higher incidence of depression in patients with neurologic disease could reflect a biologic manifestation of the disease, the impact of functional impairments upon mood, a combination of both, or a reciprocal process in which both function and mood negatively reinforce 1 another. Finally, our previous psychosocial studies of patients with histiocytosis and their caregivers have suggested a constellation of anxiety and distress emanating from, and compounded by, the features of navigating a rare disease, specifically diagnostic delay, social isolation, and uncertainty about the future.42,43 Our finding that moderate or severe depression is significantly associated with a longer duration of illness corroborates the idea that enduring a rare and poorly recognized disease can have a lasting impact on mood, even after diagnosis.

Others have also shown perceived cognitive symptom burden to be associated with anxiety and depression. Lange et al demonstrated significant correlations of the FACT-Cog subscales with anxiety and depression in healthy participants.44 These associations persist in patients with cancer in general as well as those undergoing chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplant.45-48 Other studies have not only shown a significant correlation between depression and HRQoL as measured by the FACT-G but also that depression is the leading predictor of global HRQoL, and that the FACT-G could be used as a screening tool for major depression.47,49 For histiocytosis, there is a spectrum of poorly understood neurologic phenomena including neurodegenerative disease in LCH and ECD, reduction of brain volumes in LCH and ECD, and neurocognitive symptoms in LCH survivors.50-53 The spectrum of neurologic manifestations of RDD and others disease subtypes is less characterized. Altogether, however, there is some rationale to propose that perceived cognitive symptom burden is itself a disease manifestation in some patients. The caveat should be noted that perceived cognitive symptoms may reflect physical symptoms such as fatigue, psychological distress, or other experiences of illness intrusiveness rather than objective deficits, suggesting that these also merit investigation in these diseases.54-57

In a 2023 update, American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommended education regarding depression and anxiety be offered to all oncology patients and endorsed a stepped-care model of interventions based on severity including, but not limited to, behavioral therapy, structured physical activity, and psychosocial interventions.58 Additionally, psychotherapeutic interventions have been shown to be effective for depression in patients with cancer, and cognitive behavioral therapy was demonstrated as effective for anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer.59,60 Furthermore, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society for Integrative Oncology have recommended integrative medicine approaches such as mindfulness-based interventions, yoga, and music therapy to address symptoms of anxiety and depression.61 More research is needed to understand how to best educate and increase access to these evidence-based interventions for patients with HNs.

Our study has some limitations. This registry-based, cross-sectional cohort is heterogeneous by design. Anxiety and depression were based on patient rather than clinician reporting; however, HADS was validated against clinician rating. Clinical or social factors potentially worsening or mitigating anxiety and depression, such as renal impairment on the 1 hand, or support group membership on the other, were not ascertained for our study; therefore, there is potential influence on mood that we have not measured. Attempted suicides were not systematically collected in the registry, however, 2 were documented during clinical follow-up. We did not collect information on psychological interventions or medications for anxiety or depression management, which may have influenced the observed outcomes such that the rates reported are conservative. Furthermore, the distribution of anxiety and depression categories at baseline and 12-months precluded any analyses investigating associations with change over time. However, because most patients were clinically stable, the associations identified with baseline anxiety and depression will persist at 12-months. Although the sample size of our study is unprecedented in this set of diseases, we were only able to assess ∼60% longitudinally.

Using a registry-based study design of patients with HNs paired with PRO-based outcomes, we found that anxiety and depression were prevalent, stable over time, and correlated with financial burden, symptom severity, cognitive function, and HRQoL. Offering education regarding depression and anxiety, increasing access to psychotherapeutic and integrative medicine interventions, and maximizing efforts to manage disease symptomatology are warranted in patients with HNs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the patients with Erdheim-Chester disease who are contributing to the ongoing registry.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748) and Population Sciences Research Program award (E.L.D. and K.S.P.), as well as the National Cancer Institute (R37CA259260; E.L.D. and K.S.P.). This was also supported by the Frame Family Fund (E.L.D.), the Joy Family West Foundation (E.L.D.), the Applebaum Foundation (E.L.D.), and the Erdheim-Chester Disease Global Alliance (E.L.D.). This work was also supported by the National Cancer Institute 1T32CA275764-01A1 (K.S.P, P.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.S.R. was responsible for conceptualization, formal statistical analysis, interpretation, and drafting the manuscript; Y.A., D.D.C., D.F., K.B., G.G., T.M.A., P.M., J.J.M., and K.S.P. were responsible for conceptualization, interpretation, and drafting the manuscript; D.B. and A.M.M. was responsible for data collection and drafting the manuscript; E.L.D. was responsible for conceptualization, data collection, interpretation, drafting the manuscript, and supervision; and all authors reviewed and edited the final version of the manuscript and agreed with the submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.L.D. discloses unpaid editorial support from Pfizer Inc and serves on an advisory board for Opna Bio, both outside the submitted work. G.G. reports consulting fees from Recordati; royalties from UpToDate; fees for advisory board participation for Opna Bio, Seagen, and Sobi; and serves on an advisory board for SpringWorks Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eli L. Diamond, Department of Neurology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 160 East 53rd St, Second Floor Neurology, New York, NY 10022; email: diamone1@mskcc.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Eli L. Diamond (diamone1@mskcc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.