Key Points

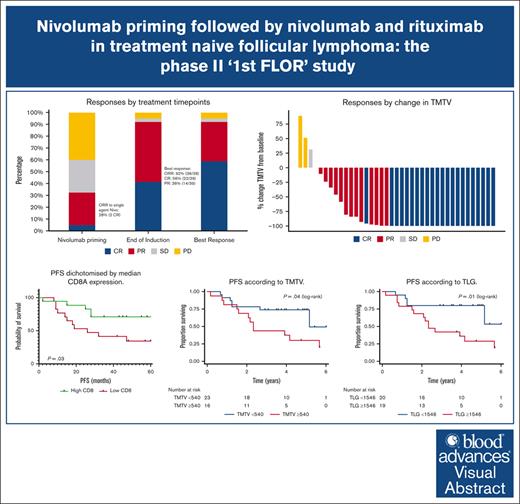

Nivolumab priming followed by combination nivolumab and rituximab was well tolerated in treatment-naïve patients with FL.

In this single arm, phase 2 study, the overall response rate was 92%, with 59% CR and a median PFS of 61 months.

Visual Abstract

Follicular lymphoma (FL) outcomes are influenced by host immune activity. CD20-directed therapy plus programmed cell death 1 inhibition (PD-1i) increases T-cell tumor killing and natural killer cell antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity. Mounting evidence supports immune priming using PD-1i before cancer directed agents. Our multicenter, phase 2 1st FLOR study enrolled 39 patients with previously untreated advanced-stage FL to receive 4 cycles of nivolumab (240 mg), then 4 cycles of 2-weekly nivolumab plus rituximab 375 mg/m2 (induction), then 1 year of monthly nivolumab (480 mg) plus 2 years of 2-monthly rituximab maintenance. Participants with complete response (CR) after nivolumab priming continued nivolumab monotherapy. The primary end point was toxicity during induction. Adverse events of grade ≥3 during induction occurred in 33% (n = 13); most commonly elevated amylase/lipase (15%), liver enzyme derangement (11%), and infection (10%). Three patients discontinued nivolumab secondary to toxicity. Overall response rate was 92% (CR, 59%). Median follow-up was 51 months. Median and 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) were 61 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 2-72) and 58% (95% CI, 34-97); 70% of responders remained in CR. The 4-year overall survival was 95%. High baseline total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) and total lesion glycolysis conferred inferior PFS (P = .04 and P = .02). Additionally, high baseline tumor CD8A gene expression was associated with improved PFS (P = .03). Nivolumab priming followed by nivolumab-rituximab in treatment-naïve FL is associated with favorable toxicity and high response rates, potentially providing an alternative to chemotherapy. TMTV and high tumor CD8A expression are promising immunotherapy biomarkers for FL. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03245021.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL), the most common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rises in incidence with advancing age and, despite a relapsing/remitting nature, necessitates treatment in most patients.1-3 First-line treatment commonly consists of combination anti-CD20–monoclonal antibody plus either chemotherapy4 or lenalidomide.5 Rituximab monotherapy is an extremely well-tolerated alternative,6-8 but many patients relapse within 1 to 2 years.8 Conversely modern immunochemotherapy combinations offer 7-year remissions exceeding 50% but are associated with grade ≥3 toxicity in 65% to 75% in randomized studies.5,8 Unsurprisingly, older patients are overrepresented in the adverse event (AE) experience, with a resultant greater impact on quality of life.9,10 Newer regimens offering comparable efficacy to chemotherapy, with fewer AEs, are needed.

FL outcomes are heavily influenced by the presence and activity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes within the tumor microenvironment.11 Expression of inhibitory immune checkpoints, programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligands, programmed cell death ligand 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2), on either lymphoma cells, or the surrounding immune cells impairs immune antitumor pathways.12,13 PD-1 pathway blockade with agents such as nivolumab or pembrolizumab stimulates antitumor T-cell activity and enhances natural killer cell antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.14,15 These immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized outcomes of many solid and lymphoid cancers.16-19

In FL, a phase 1 trial of nivolumab reported an overall response rate (ORR) of 40% and complete response (CR) in 10% in relapsed/refractory disease,20 yet a phase 2 study described a 4% ORR in heavily pretreated FL.21 A subsequent study of pembrolizumab with rituximab in 30 patients with rituximab-sensitive relapsed FL yielded ORR and CR rates of 67% and 50%, respectively, highlighting the synergism between these agents. The combination was very tolerable with grade 3/4 AEs in only 17% of patients. 22

Data from other malignancies suggest earlier ICI use may improve efficacy because of administration when host immunity is relatively preserved.16,17 Further data suggest that commencing ICI therapy before cytotoxic treatment potentially improves outcomes by so-called “immune priming.”23-25

Here, we report the results from our phase 2 study assessing nivolumab “priming” followed by nivolumab plus rituximab in treatment-naïve, advanced-stage FL with comprehensive preplanned biomarker and positron emission tomography (PET) radiomics analysis.

Methods

The “1st FLOR” study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03245021) was an investigator-initiated open-label multicenter phase 2 study.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with treatment-naïve, stage II to IV, histologically proven grade 1 to 3A FL according to the World Health Organization classification.26 Stage II disease was encompassable in a single radiotherapy field. Patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 to 2, with adequate organ function and required treatment as per Group d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF),27 British National Lymphoma Investigation,28 or in the absence of these, required a reason as per the treating investigator, for example pain. Key exclusions were prior ICIs or T-cell–engaging therapies, active autoimmune disease, recent malignancy, immunosuppression (eg, daily prednisolone of ≥10 mg), interstitial lung disease, central nervous system involvement, active hepatitis B or C, and positive HIV serology. See the supplemental Appendix for full eligibility criteria.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by an independent ethics committee (HREC/16/Austin/396). All patients provided written informed consent.

Study treatment

Induction treatment consisted of nivolumab priming 240 mg IV every 2 weeks for 4 cycles followed by PET/computed tomography (CT) response assessment. Patients achieving a complete metabolic response continued with nivolumab alone whereas those with less than complete metabolic response commenced combination nivolumab plus rituximab 375 mg/m2 IV for 4 further cycles. After completion of the induction phase, all patients achieving a response underwent maintenance nivolumab 480 mg IV every 4 weeks for 12 months total and those who had received rituximab during induction continued with maintenance rituximab 375 mg/m2 IV 12 weekly for 2 years (8 doses) as per the study schema in supplemental Figures 1 and 2.

Study assessments

Histology was confirmed by central pathology review.

Combined 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET and noncontrast CT was performed at baseline, after 4 cycles nivolumab, at end of induction, after maintenance cycles 5 and 11, then at end of treatment (24 months), or in the event of disease progression.

Safety assessments were performed before each cycle. Follow-up continued until 5 years after treatment.

End points and statistical analysis

Because of the paucity of data regarding ICI safety in treatment-naïve FL at the time of study conception, the primary end point was the rate of grade ≥3 toxicity occurring during induction treatment (ie, first 16 weeks). In previously untreated patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma receiving R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), the standard of care at time of study inception, the overall grade 3/4 toxicity rate is 71%.29 A Simon 2-stage design was used. The planned statistical design at study inception was as follows: in the first stage, 19 patients will be accrued. If there are ≤6 patients with no grade ≥3 AEs in these 19 patients, the study will be stopped. Otherwise, 20 additional patients will be accrued for a total of 39. The null hypothesis will be rejected if ≤16 patients without grade ≥3 toxicities are observed in 39 patients during induction that is an unacceptable treatment-related grade ≥3 toxicity rate of 70%. This design yields a type 1 error rate of 0.05 and power of 0.8 when the true grade 3/4 toxicity rate is 70%.

Secondary end points were overall treatment emergent toxicity, response rates, progression-free survival (PFS; time from study entry to disease progression, relapse, or death from any cause), and overall survival (OS) estimated by Kaplan-Meier methodology.30 Response was determined by central review according to PET/CT Lugano 2014 criteria.31 AEs were defined per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03. Associations between patient/disease characteristics with response and survival were evaluated by logistic regression (odds ratio [OR]) and Cox proportional hazards regression (hazard ratio [HR]), respectively.

A preplanned exploratory analysis was undertaken to identify PET-imaging and tissue markers associated with response. PET-CT scans were performed on Australian Radiopharmaceutical Trials Network–accredited scanners and PET metrics (total metabolic tumor volume [TMTV], maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax], and total lesion glycolysis [TLG]) were calculated using MIMEncore (MIM Software Inc, OH). TMTV was calculated using the fixed absolute SUV of >4 method, with manual removal of physiologic/nonmalignant disease in the field of view. Receiver operator curve analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff values for TMTV, TLG, and SUVmax analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue biopsy samples were obtained from 34 patients before commencing treatment. RNA was extracted using Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded kit according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and quantified by Qubit RNA high sensitivity assay kit. RNA expression was digitally quantified using the NanoString PanCancer Immune panel (730 immune-related genes plus 40 housekeeping genes), as previously published.32 Data were normalized as per the standard Nanostring Advanced Analysis protocols and gene expression analyzed. Associations between gene expression and outcomes were evaluated by the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical analysis was performed on GraphPad Prism.

Results

Patients

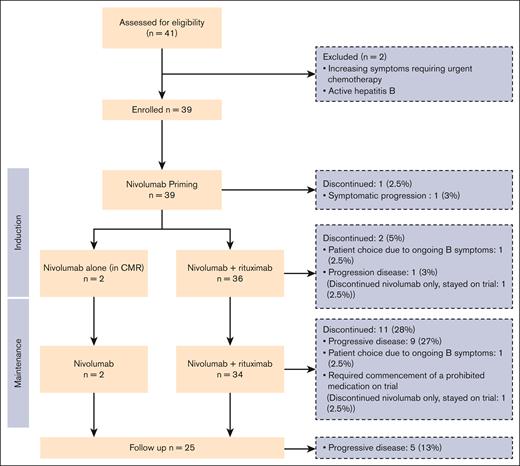

Thirty-nine patients were enrolled between October 2017 and April 2020. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 41 patients were screened, with 2 excluded (1 due to active hepatitis B infection, and 1 requiring urgent cytotoxic treatment for rapid symptom evolution). Thirty-one patients fulfilled GELF criteria at study entry. Reasons for treatment in the 8 that did not, were: painful lymphadenopathy/extranodal disease in 2, and significant clinical or radiological disease progression in the preceding 3 months in 6. All enrolled patients commenced nivolumab, with 2 continuing nivolumab alone. Thirty-six received combination nivolumab-rituximab from cycle 5 onward, with 1 discontinuing treatment before combination immunotherapy because of symptomatic disease progression (Figure 1).

Patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristic . | N = 39 . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 54 (28-79) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 19 (49) |

| Male | 20 (51) |

| Ann Arbor stage (%) | |

| III | 13 (33) |

| IV | 26 (67) |

| ECOG performance status score (%) | |

| 0 | 29 (74) |

| 1 | 10 (26) |

| B-symptoms present (%) | 9 (23) |

| Bulk of ≥7 cm (%) | 9 (23) |

| Extranodal sites, ≥1 (%) | 29 (74) |

| FL histological grade (%) | |

| 1-2 | 30 (77) |

| 3A | 8 (21) |

| Treatment eligibility (%) | |

| GELF criteria present∗ | 31 (80) |

| Rapid disease progression in prior 3 mo | 6 (15) |

| Other (symptomatic lymphadenopathy or painful bone lesions) | 2 (5) |

| FLIPI risk score (%) | |

| Low risk (0-1) | 10 (26) |

| Intermediate risk (2) | 22 (56) |

| High risk (3) | 7 (18) |

| Characteristic . | N = 39 . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 54 (28-79) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 19 (49) |

| Male | 20 (51) |

| Ann Arbor stage (%) | |

| III | 13 (33) |

| IV | 26 (67) |

| ECOG performance status score (%) | |

| 0 | 29 (74) |

| 1 | 10 (26) |

| B-symptoms present (%) | 9 (23) |

| Bulk of ≥7 cm (%) | 9 (23) |

| Extranodal sites, ≥1 (%) | 29 (74) |

| FL histological grade (%) | |

| 1-2 | 30 (77) |

| 3A | 8 (21) |

| Treatment eligibility (%) | |

| GELF criteria present∗ | 31 (80) |

| Rapid disease progression in prior 3 mo | 6 (15) |

| Other (symptomatic lymphadenopathy or painful bone lesions) | 2 (5) |

| FLIPI risk score (%) | |

| Low risk (0-1) | 10 (26) |

| Intermediate risk (2) | 22 (56) |

| High risk (3) | 7 (18) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

GELF criteria includes: any tumor mass of >7 cm diameter, ≥3 nodal sites (each >3 cm diameter), B-symptoms, splenomegaly, compression syndrome, serous effusion, leukemic phase, peripheral blood cytopenias, LDH, or β-2-microglobulin above the upper limit of normal.

Safety

AEs are summarized in Table 2. All patients experienced at least 1 AE during the study; most low grade. The study met its primary end point with 13 of 39 (33%) grade ≥3 AEs occurring during induction. Grade ≥3 AEs occurred in 23 of 39 (59%) patients overall, and serious AEs occurred in 18 (46%) patients, of which infection (6/20), fever (2/20), and pancreatitis (2/20) were most common. There were no deaths due to toxicity (full serious AE details in supplemental Table 1).

AEs

| AE . | Grade 1∗ (%) . | Grade 2∗ (%) . | Grade 3 (%) . | Grade 4 (%) . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AEs† | 37 (95) | 35 (90) | 18 (46) | 5 (13) | 39 (100) |

| Infection | 12 (31) | 16 (41) | 4 (10) | 32 (82) | |

| Fatigue/lethargy | 21 (54) | 3 (8) | 24 (62) | ||

| Musculoskeletal‡ | 13 (33) | 9 (23) | 2 (5) | 24 (62) | |

| Rash‡ | 14 (36) | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 23 (60) | |

| Elevated liver enzymes‡ | 6 (15) | 7 (18) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 17 (44) |

| Abdominal pain | 10 (26) | 6 (15) | 16 (41) | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 11 (28) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 16 (41) | |

| Diarrhea‡ | 8 (21) | 5 (13) | 13 (34) | ||

| Rituximab infusion–related reaction | 5 (13) | 7 (18) | 12 (31) | ||

| Headache | 5 (13) | 6 (15) | 11 (28) | ||

| Dyspnea | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 9 (23) | ||

| Nivolumab infusion–related reaction | 3 (8) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 9 (23) | |

| Anorexia/weight loss | 5 (13) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 9 (23) | |

| Amylase/lipase increased‡ | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 8 (21) |

| Insomnia | 5 (13) | 3 (8) | 8 (21) | ||

| Mood disturbance | 5 (13) | 3 (8) | 8 (21) | ||

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 4 (10) | 3 (8) | 7 (18) | ||

| Hyperglycemia | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 7 (18) | |

| Cough | 6 (15) | 1 (3) | 7 (18) | ||

| Pruritus‡ | 4 (10) | 3 (8) | 7 (18) | ||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 6 (15) | |

| Limb edema | 6 (15) | 6 (15) | |||

| Fever | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 6 (15) | ||

| Dry mouth‡ | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (13) | ||

| Iron deficiency | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 5 (13) | ||

| Hypotension | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 5 (13) | |

| Hyperhidrosis | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Anemia | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Constipation | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Bruising | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Acute kidney injury‡ | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | |

| Thrush | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | |||

| Pancreatitis‡ | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | ||

| Autoimmune hepatitis‡ | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |||

| Adrenal insufficiency‡ | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |||

| Bile duct obstruction | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| AE . | Grade 1∗ (%) . | Grade 2∗ (%) . | Grade 3 (%) . | Grade 4 (%) . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AEs† | 37 (95) | 35 (90) | 18 (46) | 5 (13) | 39 (100) |

| Infection | 12 (31) | 16 (41) | 4 (10) | 32 (82) | |

| Fatigue/lethargy | 21 (54) | 3 (8) | 24 (62) | ||

| Musculoskeletal‡ | 13 (33) | 9 (23) | 2 (5) | 24 (62) | |

| Rash‡ | 14 (36) | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 23 (60) | |

| Elevated liver enzymes‡ | 6 (15) | 7 (18) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 17 (44) |

| Abdominal pain | 10 (26) | 6 (15) | 16 (41) | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 11 (28) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 16 (41) | |

| Diarrhea‡ | 8 (21) | 5 (13) | 13 (34) | ||

| Rituximab infusion–related reaction | 5 (13) | 7 (18) | 12 (31) | ||

| Headache | 5 (13) | 6 (15) | 11 (28) | ||

| Dyspnea | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 9 (23) | ||

| Nivolumab infusion–related reaction | 3 (8) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 9 (23) | |

| Anorexia/weight loss | 5 (13) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 9 (23) | |

| Amylase/lipase increased‡ | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 8 (21) |

| Insomnia | 5 (13) | 3 (8) | 8 (21) | ||

| Mood disturbance | 5 (13) | 3 (8) | 8 (21) | ||

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 4 (10) | 3 (8) | 7 (18) | ||

| Hyperglycemia | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 7 (18) | |

| Cough | 6 (15) | 1 (3) | 7 (18) | ||

| Pruritus‡ | 4 (10) | 3 (8) | 7 (18) | ||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 6 (15) | |

| Limb edema | 6 (15) | 6 (15) | |||

| Fever | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 6 (15) | ||

| Dry mouth‡ | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (13) | ||

| Iron deficiency | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 5 (13) | ||

| Hypotension | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 5 (13) | |

| Hyperhidrosis | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Anemia | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Constipation | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Bruising | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | ||

| Acute kidney injury‡ | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) | |

| Thrush | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | |||

| Pancreatitis‡ | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | ||

| Autoimmune hepatitis‡ | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |||

| Adrenal insufficiency‡ | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |||

| Bile duct obstruction | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase.

AEs observed in ≥10% patients and all grade ≥3 AEs reported.

Total AEs includes all patients. Musculoskeletal AEs include arthralgia, myalgia, bone pain, and joint effusion; liver enzymes include ALP, GGT, ALT, and AST.

Possible irAEs.

Immune-related AEs (irAE) potentially attributable to nivolumab are listed in Table 2. Grade ≥3 irAEs occurred in 10 of 39 (26%) patients. Three patients required nivolumab cessation in the setting of grade 3 irAEs (all continued trial rituximab monotherapy). The first ceased nivolumab at the end of induction was due to grade 3 pancreatitis, hepatitis, and rash occurring simultaneously, and the second was secondary to pancreatitis alone during the maintenance phase. The third ceased nivolumab after development of an acute kidney injury, which could not be attributable to another cause. A renal biopsy was not performed. Most common irAEs included musculoskeletal (62%), rash (60%), diarrhea (34%), and asymptomatic lipase/amylase elevation (21%). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of grade ≥3 irAEs between patients aged >60 years and those aged ≤60 years (OR, 0.56; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.11-2.90; P = .5). Seventy percent of patients experiencing a grade ≥3 irAE achieved CR vs 30% in those with no grade ≥3 irAEs (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 0.41-8.82; P = .41).

Three patients discontinued treatment in the absence of toxicity or disease progression: 2 because of ongoing B-symptoms, and 1 requiring commencement of a prohibited medication (methotrexate) for management of a new inflammatory arthritis, which commenced while on rituximab monotherapy.

Efficacy

All patients were evaluable for response, presented in Figure 2. ORR was 92%, with CR achieved in 59%. The median time to CR was 6.5 months (range, 1-25) with 7 (18%) patients, who achieved a partial response (PR) after induction, converting to a CR during maintenance therapy. At data cutoff, 16 of 23 (70%) of CRs were ongoing.

Treatment responses. (A) Responses by treatment time points. (B) Responses by change in TMTV. SD, stable disease.

Treatment responses. (A) Responses by treatment time points. (B) Responses by change in TMTV. SD, stable disease.

The response to 4 cycles of priming nivolumab was 5% CR (n = 2), 26% PR (n = 10), 28% stable disease (n = 11), and 41% progressive disease (PD; n = 16). The 2 patients who achieved a CR to nivolumab priming were classified into high and intermediate FLIPI (Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index) risk groups. The high-risk patient was characterized by advanced age, stage IV disease, >4 nodal sites, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The intermediate-risk patient had stage IV disease and elevated LDH.

With a median follow-up of 51 months (range, 2-72), the median duration of response was 59 months (range, 0-68), with 14 (36%) experiencing PD requiring treatment cessation, and an additional 5 (13%) progressing during follow-up. Ten patients progressed within 24 months of treatment commencement. Of those progressing, 14 of 19 required further treatment. The median PFS and OS was 61 months (95% CI, 2-72) and not reached (95% CI,18-72), respectively, with 4-year PFS and OS of 58% (95% CI, 41-72) and 95% (95% CI, 81-99), respectively (Figure 3).

Sex, stage, extranodal disease, elevated LDH, bulk of ≥7 cm, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status, high tumor burden by GELF criteria, and the FLIPI did not significantly affect PFS on univariable analysis.

At last follow-up, 37 (95%) patients were alive, with 20 (51%) in remission and 17 (44%) demonstrating progression/relapse. Two (5%) deaths occurred; 1 due to progressive lymphoma (with biopsy-proven transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and the other from COVID-19 pneumonia, 4 months after R-CHOP chemotherapy for FL progression.

Biomarker analysis

Gene expression profiling was performed on 34 available pretreatment tumor biopsies. All samples passed Nanostring quality control parameters. CD8A expression was significantly higher in tumor tissue from patients who achieved a CR or PR after nivolumab alone (CR/PR, n = 11; stable disease/PD, n = 22; P = .02). A significant increase in CD8A was also evident in those patients who did not relapse (relapse, n = 18; no relapse, n = 16; P = .02) and in patients who achieved a CR as best evaluable response (CR, n = 19; PR/PD, n = 15; P = .03; Figure 4A). Furthermore, patients with high CD8A expression within the tumor before therapy demonstrated a significantly longer PFS (high CD8A, n = 17; low CD8A, n = 17; P = .03; Figure 4B). Of note, tumor tissue and CD4, PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2, lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein), T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain, and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing molecule 3 gene expression was not associated with achieving response or survival outcomes.

CD8 T cells are predictive of response. (A) CD8A gene expression according to patient response. (B) PFS dichotomized by median CD8A expression. SD, stable disease.

CD8 T cells are predictive of response. (A) CD8A gene expression according to patient response. (B) PFS dichotomized by median CD8A expression. SD, stable disease.

PET kinetics

Maximal changes in TMTV were concordant with PET/CT Lugano responses as depicted in Figure 2B, with 35 of 39 (90%) patients achieving some reduction in TMTV. Median baseline TMTV, TLG, and SUVmax were 427 cm3 (range, 0-2488), 1535 (range, 0-7161), and 12 (range, 0-106), respectively. Receiver operator curve analysis for PFS showed that the optimal cutoff values for TMTV, TLG, and SUVmax at baseline were 540 cm3 (sensitivity, 63%; specificity, 80%; and area under the curve [AUC], 0.72), 1546 (sensitivity, 74%; specificity, 75%; and AUC, 0.74), and 12.25 (sensitivity, 53%; specificity, 65%; and AUC, 0.59), respectively. Using the aforementioned cutoffs, both high baseline TMTV and TLG were significantly associated with an inferior PFS (TMTV: HR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.02-6.70; P = .04; TLG: HR, 3.39; 95% CI, 1.21-9.48; P = .02), whereas SUVmax was not (HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 0.69-4.33; P = .24; Figure 5). The 2 patients that responded to nivolumab priming had low TMTV and TLG, confirming the prognostic impact in this subgroup.

Survival according to PET metrics. (A) PFS according to TMTV. (B) PFS according to TLG.

Survival according to PET metrics. (A) PFS according to TMTV. (B) PFS according to TLG.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our phase 2 immune-priming study is the first to explore the synergy of B-cell targeting with natural killer cell–mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity from rituximab, partnered with nivolumab-induced T-cell stimulation in treatment-naïve FL. We demonstrated this combination to be efficacious with a favorable toxicity profile. The primary end point was met with grade ≥3 toxicity in only 33% of patients during induction and overall therapy-related grade 3/4 toxicity in 59%, with no treatment-related mortality, and cessation of nivolumab required in only 3 patients (7%) due to irAEs. Importantly, there was no difference in grade ≥3 irAEs in patients aged >60 years, compared with younger patients. The toxicity was notably lower than with standard rituximab/obinutuzumab chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide for which reported grade 3 to 5 AE rates were 65% to 75% in phase 3 trials such as GALLIUM and RELEVANCE. When comparing immunochemotherapy-treated patients to our cohort, 15% vs 7% required discontinuation of at least 1 treatment due to AEs, and treatment-related deaths occurred in 4% vs 0% of patients, respectively. Additionally, in the RELEVANCE study, 36% of patients required dose reductions due to toxicity, whereas none were required in our cohort.5,33

Although our primary end point of grade 3/4 AEs during induction was 33% and much lower than many equivalent duration chemotherapy-based regimens, it is important to note, this increased to 59% during the entire treatment phase of 2 years and 4 months with the addition of maintenance therapy. Although these were predominantly grade 3 rather than 4, with no treatment-related deaths and minimal treatment impact, this important observation needs to be considered for future trials that extend duration of treatments beyond that of conventional chemoimmunotherapy in treatment-naïve FL, which has overall an excellent prognosis.

With the known caveats of cross-trial comparisons, our ORR of 92% and median PFS of 61 months from nivolumab priming followed by nivolumab-rituximab appears superior to that reported in first-line rituximab monotherapy trials of ∼75% and 24 months, respectively, although a randomized trial is required to test this definitively.8,34,35 The SAKK 35/98 rituximab monotherapy trial in 38 patients with treatment-naïve FL demonstrated a 5-year event free survival of 45% with 8 doses of single-agent rituximab, compared with our 4-year PFS of 58%.8 Notably, eligibility criteria for the SAKK study permitted much lower risk patents than our trial, which was modeled on the GELF criteria, with SAK 35/98 requiring only 2 measurable FL lesions on anatomical imaging, with at least 1 being ≥2 cm. Our study efficacy also exceeds results previously reported with combinations of ICI and anti-CD20 antibodies in relapsed FL cohorts, in which obinutuzumab plus atezolizumab yielded ORR of 54% (CR, 23%) and a median PFS of 9 months36 and in rituximab-sensitive patients, for whom an ORR of 67% (CR, 50%) and a median PFS of 12 months was demonstrated from the addition of pembrolizumab to rituximab.22

Notably, our study population had a similar risk profile to the aforementioned FL phase 3 studies GALLIUM33 and RELEVANCE,5 with >70% of patients comprising intermediate- and high-risk FLIPI groups. Although our ORR of 92% is comparable with these phase 3 studies evaluating immunochemotherapy or rituximab-lenalidomide (ORR, 79%-84%), the PET CR rate and 3-year PFS with immunochemotherapy in GALLIUM was 76% and 80%, respectively, compared with a CR rate of 56% and 4 year PFS of 58% (95% CI, 41-72) in our cohort. Noting the different time points of reporting PFS, and the likely overlapping of CIs, we acknowledge that cross-trial comparisons do have their limitations with our much smaller sample size and minor differences in patient cohorts. Follow-up is ongoing, but, at present, our 4-year OS is excellent at 95%. In addition, CRs occurred much later in some patients from our cohort with nivolumab-rituximab compared with chemotherapy-based regimens.5,37 Given that the median time to CR in this trial was 6.5 months, our immunotherapy approach is potentially less suited to patients with rapidly deteriorating symptomatology and/or rapid disease progression in which prompt cytoreduction may be required. Anticipating this, we incorporated the following proviso into the study protocol: those who have major PD and/or symptomatic PD will come off study and have treatment according to local practice.

Predicting which patients will benefit from a less intensive, less toxic approach such as combination nivolumab-rituximab is paramount to the progress of ICI in FL. In relapsed/refractory FL, Nastoupil et al demonstrated that a tumoral high baseline CD8+ T-effector score was associated with CR and improved PFS from pembrolizumab-rituximab,22 and increased CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were associated with FL disease response to combination obinutuzumab-atezolizumab.36 Similarly in our study, we demonstrated, to our knowledge, for the first time, that high CD8A gene expression correlated with nivolumab priming monotherapy response, achievement of a CR as best response on study, and a prolonged PFS, indicating that patients with preexisting robust intratumoral immunity are more likely to benefit from an immunotherapy-driven approach. In addition, the inferior PFS associated with high baseline TMTV and TLG in frontline FL chemoimmunotherapy studies was replicated with our ICI-based regimen.38,39

Although results of single-agent nivolumab in both relapsed FL and during the priming phase of our first-line population are disappointing, with only 2 of our patients achieving CR from 8 weeks of monotherapy treatment, the favorable efficacy of nivolumab-rituximab in this trial support further evaluation of ICI priming and combination approaches, particularly with synergistic therapies known to augment immune stimulation. As we and others have demonstrated, rational combinations and ICI sequencing with active immunomodulatory agents offer improved outcomes with favorable toxicity.23 Our group has subsequently explored triplet combinations using obinutuzumab-atezolizumab with radiotherapy, and rituximab-nivolumab plus golcadomide in ongoing first-line FL trials.40,41 These, as well as additional checkpoint inhibitors, bispecific immunotherapies,42-44 and chimeric antigen receptor T cells45,46 are expanding immune-manipulating approaches for FL.

In summary, to our knowledge, for the first time, we have shown that exploiting the immune dysregulation of treatment-naïve FL with nivolumab “priming” followed by nivolumab-rituximab has demonstrated very tolerable toxicity and high overall and durable responses. Furthermore, high baseline TMTV (≥427 cm3), TLG (≥1535), and high CD8A gene expression were strong prognostic factors in our cohort. Ongoing efforts harnessing synergy between immunotherapy and immune-modulating tumoricidal agents to improve durable complete remission rates while minimizing significant toxicity are underway with the next generation of immunotherapies. Future research must incorporate comprehensive but rational biomarker work to tailor the use of these active, tolerable chemotherapy-free agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charmaine Smith and Jodie Palmer for assistance with data collation. Bristol Myers Squibb provided nivolumab.

This study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. C.K. and E.A.H. are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia investigator grants 2017033 and 2020/MRF1194324.

A.B. is a PhD candidate at The University of Melbourne. This work is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the PhD and is supported by a research training program scholarship.

Authorship

Contribution: E.A.H., G.C., L.C., and S.T.L. designed the study; A.B., E.A.H., G.C., M.G., K.M., and D.L. conducted the study, recruited and followed up with patients, and collected the data; M.B. and C.K. were responsible for translational testing; A.B., E.A.H., G.C., M.G., K.M., M.B., and C.K. were responsible for data analysis; and all authors were involved in the interpretation of data, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.B. reports honoraria from advisory board participation with Roche, Novartis, BeiGene, and Gilead. G.C. reports research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, HUTCHMED, Regeneron, Amgen, Roche, Merck, AstraZeneca, Pharmacyclics, Bayer, Incyte, and Dizal Pharma, and consultant/advisory roles with Bristol Myers Squibb, Regeneron, and Takeda. D.L. reports honoraria/advisory roles with Roche and Gilead. K.M. reports honoraria from/advisory board participation with BeiGene and AbbVie. A.M.S. reports research funding (paid to institution) from EMD Serono, ITM, Telix Pharmaceuticals, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Fusion Pharmaceuticals, Cyclotek, MedImmune, Antengene, Humanigen, and Telix Pharmaceuticals, and advisory board roles with Imagion and ImmunOs. C.K. reports honoraria from/consultancy with Roche, Takeda, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, and BeiGene. E.A.H. reports research funding (paid to institution) from Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck KGaA, AstraZeneca, TG Therapeutics, and Merck; consultant or advisory roles with Roche (paid to institution), Merck Sharpe & Dohme (paid to institution), AstraZeneca (paid to institution), Gilead, Antengene (paid to institution), Novartis (paid to institution), Regeneron, Janssen (paid to institution), Specialised Therapeutics (paid to institution), and Sobi; and reports travel expenses from AstraZeneca. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eliza A. Hawkes, Department of Hematology, Olivia Newton John Cancer Research Institute at Austin Health, PO Box 5555, Heidelberg, VIC 3084, Australia; email: eliza.hawkes@onjcri.org.au.

References

Author notes

Requests for nonidentifiable data for valid academic reasons as judged by the trial management group will be granted, with appropriate data sharing agreement, and should be addressed to the corresponding author, Eliza A. Hawkes (eliza.hawkes@onjcri.org.au). Data will be made available 3 months after publication for a period of 5 years after the publication. Individual participant data will not be shared.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.