Key Points

Additional mutations are associated with absence of CR to first-line treatment in ET.

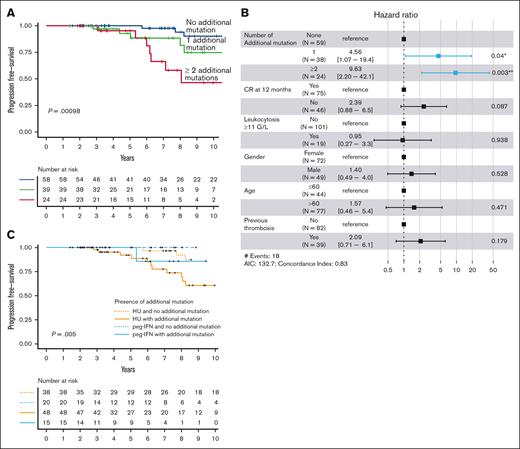

The number of additional mutations at diagnosis was associated with hematologic progressions.

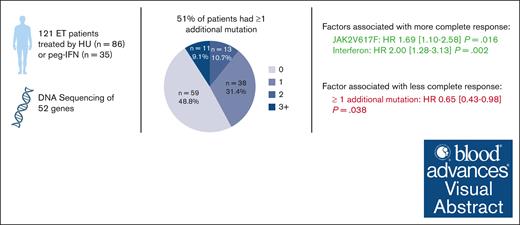

Visual Abstract

Patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) have a chronic evolution with a risk of hematologic transformation associated with a dismal outcome. Because patients with resistance or intolerance have adverse prognosis, it is important to identify which patient will respond to first-line treatment. We, therefore, aim to describe the association between additional mutations and response to first-line treatment in patients with ET. In this retrospective study, we analyzed the molecular landscape of 121 ET patients first-line treated with hydroxyurea (HU; n = 86) or pegylated interferon (peg-IFN; n = 35). Patients undergoing peg-IFN therapy were younger and had higher proportion of low and very low risk of thrombosis recurrence. A total of 62 patients (51%) had ≥1 additional mutations at diagnosis. At 12 months of treatment, 75 patients (62%) achieved complete response (CR), 37 (31%) partial response, and 7 (6%) no response. The presence of at least 1 additional mutation at diagnosis was associated with not achieving CR (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; P = .038), whereas treatment with peg-IFN was associated with higher CR (HR, 2.00; P = .002). The number of additional mutations at diagnosis was associated with hematologic progressions (P < .0001). None of the patients receiving peg-IFN therapy progressed to myelofibrosis, whereas 16 of 86 patients (19%) treated with HU developed secondary myelofibrosis. In conclusion, our results suggest that the presence of at least 1 additional mutation at diagnosis is associated with failure to achieve CR and also with an increased risk of hematologic evolution.

Introduction

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is BCR::ABL1-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) driven by mutations in the JAK2 (50%-60% of patients), CALR (20%-30%), or MPL (2%-5%) driver genes, whereas 10% to 20% of patients have no driver mutation, so-called “triple negative.”1-10 A history of thrombosis at or before diagnosis occurs in ∼20% to 40% of cases, and the main source of morbidity during follow-up is vascular events, with an incidence of 1.9% patient-years of recurrent thrombosis.11,12 Patients with ET can also progress to myelofibrosis (MF) in 9% of cases at 10 years and to acute myeloid leukemia in 2.6% to 7.5% of cases at 20 years, both associated with an adverse outcome.13,14

According to the European Leukemia Network and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,15,16 cytoreduction is recommended for patients at high risk of thrombosis, that is, patients aged >60 years or with prior thrombosis. Hydroxyurea (HU) is recommended as first-line cytoreductive therapy, but interferon may also be used because it is known to reduce the JAK2 allele burden, which may limit progression.15,17,18 Twenty percent of patients develop resistance or intolerance to HU, which is associated with a higher rate of transformation to MF and a high risk of death.19

With the rise of high-throughput sequencing, also known as next-generation sequencing, the mutational landscape of MPN is being better understood.20 Additional somatic mutations, besides the driver mutation, is observed in ∼45% of patients with ET, and some of these, such as TP53 or spliceosome mutations, may be associated with progression to MF or acute leukemia.21,22 This has led to the development of a prognostic score, the mutation-enhanced international prognostic systems, which predicts overall survival in patients with ET by incorporating “adverse mutations” in SRSF2, SF3B1, U2AF1 and TP53 genes.23

Although additional mutations seem associated with prognosis in ET, few studies have evaluated their association with treatment response, in contrast to primary myelofibrosis (PMF). In the context of primary PMF, ASXL1 and EZH2 mutations are associated with a shorter time to treatment failure, and high molecular risk mutations are associated with a loss of response to ruxolitinib.24-26 In ET, 2 studies observed that the frequency of additional mutations was associated with a worse response in patients treated with interferon, but they included only a small number of patients (39 and 31 patients, respectively).27,28

Therefore, herein, we aim to describe the association between additional mutations at diagnosis and response to first-line treatment with HU or pegylated interferon in patients with ET.

Methods

Patient selection

In this retrospective study at the University Hospital of Angers, patients were included if they were aged ≥18 years with a diagnosis of ET since 2005 according to the diagnostic criteria of the 2016/2022 World Health Organization classification (bone marrow biopsy was mandatory)29,30 and received first-line therapy with either HU or peginterferon alfa-2a (peg-IFN). All patients were enrolled into the collection “Hémopathies Malignes” of the hospital of Angers, which was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes of Angers (France) Ouest II. In accordance with the French law, a written informed consent was obtained from patients for the use of clinical and biological data, including DNA sequencing. This study was registered by the French authority Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés (French Data Protection Authority, authorization ar23-0018v0).

Definitions for risk stratification and response

Response to treatment was defined according to the 2009 European Leukemia Network (ELN) criteria31 as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and no response (NR). CR is defined as a platelet count ≤400 × 109/L, absence of disease-related symptoms, normal spleen size, and white blood cell count ≤10 × 109/L; PR applies to patients who do not fulfill the criteria for CR and have a platelet count ≤600 × 109/L or decrease >50% from baseline; and NR as any response that does not satisfy the criteria for PR. To note, spleen size was clinically evaluated. The time of CR was the day of the first observed platelet count <400 109/L, only if 2 consecutive results were obtained. Loss of response was considered in patients who lost response after achieving CR, and partial loss of response was considered in patients who transitioned from CR to PR. Overall response rate (ORR) is defined as the proportion of patients achieving CR and PR. Intolerance was defined as the discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events, and ineffectiveness was defined as a change in treatment due to treatment failure. Treatment failure was defined as platelet count exceeding 600 × 109/L or progression to MF or acute leukemia after 3 months of treatment with the maximum tolerated dose for peg-IFN and at least 2 g per day or the maximum tolerated dose of HU.

First response evaluation was assessed at 12 months (±1 month) or earlier if treatment was discontinued during the first year and then at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months (±3 months). For response assessment, follow-up data were censored at the time of treatment interruption or hematologic evolution.

Molecular analysis

For each patient, next-generation sequencing was performed on a peripheral blood DNA sample obtained at diagnosis. A panel covering all exons of 52 genes involved in myeloid malignancies was analyzed (supplemental Table 1). The sensitivity was set at 2%. Only pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations were retained for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.2 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For comparison between groups, the t test was used for continuous normally distributed variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous nonnormally distributed variables. Χ2 or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. Survival was plotted as Kaplan-Meir curves, and Cox models were run including all variables of interest with stepwise downward selection. A multistate model was run to examine the variables associated with CR or treatment discontinuation. For treatment response and survival analysis, the starting point was defined as the time of treatment initiation.

Results

Patient characteristics

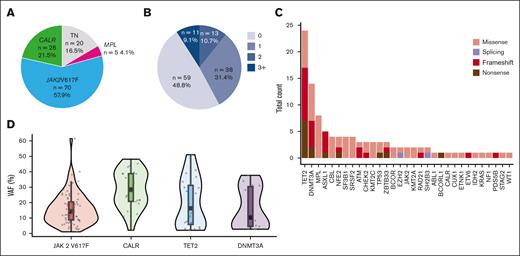

A total of 121 patients who received HU (n = 86 [71%]) or peg-IFN (n = 35 [29%]) as a first-line therapy were included (supplemental Figure 1; dose description in the supplemental Data). Treatment was initiated in most patients within the first year after diagnosis, with a median time of 2.3 months (2.1 for HU and 3.5 for peg-IFN, not significant [NS]). However, some patients began treatment several years later, with a maximum delay of 11 years (supplemental Figure 2). Among the 35 patients treated with peg-IFN, this treatment was chosen instead of HU because of age ≤60 years for 19 patients (54.3%), fitness for 12 patients (34.3%), and at the discretion of the physician for 4 patients (11.4%). At treatment initiation, patients in the peg-IFN group were younger (median age, 60 years [range, 19-72]) than patients treated with HU (67 years, [range, 23-90]), and thus, more patients receiving HU than peg-IFN were considered high risk according to ELN and revised International Prognostic Score of Thrombosis (IPSET) classifications (Table 1). Among 21 patients classified as low risk according to ELN classification, treatment initiation was motivated by extreme thrombocytosis in 13 patients (61.9%; including 1 patient with bleeding), suspicion of transient ischemic attack in 2 patients (9.5%), symptoms in 4 patients (19%), cardiovascular risk factors (IPSET high), age close to 60 years in 1 patient, and inclusion in a research protocol for 1 patient. At initiation treatment, 36% of patients treated with HU and 22.9% of those treated with peg-IFN had a prior history of thrombosis (P = .233). Of the 121 patients, 70 (58%) had a JAK2V617F driver mutation, 26 (21.5%) had a CALR mutation, 5 (4%) had a MPL mutation, and 20 (16.5%) were considered triple negative (Figure 1A). Sixty-two patients (51%) had ≥1 additional mutation at diagnosis, with a similar distribution between the 2 treatment groups (Table 1). Most patients had only 1 additional mutation (Figure 1B), with the most common additional mutations involving TET2 (19/121 [15.7%]), DNMT3A (13/121 [10.7%]), non-W515K/L MPL (8/121 [6.6%]), ASXL1 (5/121 [4.13%]), and splicing factors SRSF2 and SF3B1 (8/121 [6.6%]) genes (Table 1; Figure 1C). The distribution of variant allele frequencies of the most common genes JAK2V617F, CALR, TET2, and DMNT3A is shown in Figure 1D.

Patient characteristics at treatment initiation

| Characteristics at treatment initiation . | peg-IFN . | HU . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 35 . | n = 86 . | ||

| Clinical data | |||

| Median age, y (range) | 60 (19-72) | 67 (23-90) | <.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 18 (51.4) | 31 (36) | .17 |

| History of thrombosis, n (%) | 8 (23) | 31 (36) | .23 |

| Type of thrombosis, arterial thrombosis, n (%) | 5 (14) | 17 (20) | .41 |

| Veinous thrombosis, n (%) | 3 (9) | 14 (16) | |

| Biology | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, median (range) | 14.5 (11.9-17.2) | 14.5 (8.8-17.7) | .83 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L, median (range) | 665 (335-1772) | 729 (435-1963) | .63 |

| Leucocyte count, × 109/L, median (range) | 7.8 (3.4-12.8) | 8,3 (2.9-17.4) | .22 |

| r-IPSET | .05 | ||

| High risk, n (%) | 16 (46) | 56 (65) | |

| Intermediate risk, n (%) | 8 (23) | 20 (23) | |

| Low risk, n (%) | 4 (11) | 5 (6) | |

| Very low risk, n (%) | 7 (20) | 5 (6) | |

| ELN | .02 | ||

| High risk, n (%) | 24 (69) | 76 (88) | |

| Low risk, n (%) | 11 (31) | 10 (12) | |

| Driver mutation | .47 | ||

| JAK2 V617F, n (%) | 19 (54) | 51 (59) | |

| CALR, n (%) | 9 (26) | 17 (20) | |

| MPL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (6) | |

| TN, n (%) | 7 (20) | 13 (15) | |

| Patients with additional mutations | |||

| None, n (%) | 21 (60) | 38 (44.2) | .17 |

| ≥2, n (%) | 6 (17.1) | 18 (20.9) | .82 |

| TET2, n (%) | 3 (8.6) | 16 (18.6) | .27 |

| DNMT3A, n (%) | 4 (11.4) | 9 (10.5) | 1 |

| ASXL1, n (%) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (3.5) | .63 |

| MPL (not W515), n (%) | 5 (14.3) | 3 (3.5) | .04 |

| Splicing, n (%) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (8.1) | .43 |

| Characteristics at treatment initiation . | peg-IFN . | HU . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 35 . | n = 86 . | ||

| Clinical data | |||

| Median age, y (range) | 60 (19-72) | 67 (23-90) | <.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 18 (51.4) | 31 (36) | .17 |

| History of thrombosis, n (%) | 8 (23) | 31 (36) | .23 |

| Type of thrombosis, arterial thrombosis, n (%) | 5 (14) | 17 (20) | .41 |

| Veinous thrombosis, n (%) | 3 (9) | 14 (16) | |

| Biology | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, median (range) | 14.5 (11.9-17.2) | 14.5 (8.8-17.7) | .83 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L, median (range) | 665 (335-1772) | 729 (435-1963) | .63 |

| Leucocyte count, × 109/L, median (range) | 7.8 (3.4-12.8) | 8,3 (2.9-17.4) | .22 |

| r-IPSET | .05 | ||

| High risk, n (%) | 16 (46) | 56 (65) | |

| Intermediate risk, n (%) | 8 (23) | 20 (23) | |

| Low risk, n (%) | 4 (11) | 5 (6) | |

| Very low risk, n (%) | 7 (20) | 5 (6) | |

| ELN | .02 | ||

| High risk, n (%) | 24 (69) | 76 (88) | |

| Low risk, n (%) | 11 (31) | 10 (12) | |

| Driver mutation | .47 | ||

| JAK2 V617F, n (%) | 19 (54) | 51 (59) | |

| CALR, n (%) | 9 (26) | 17 (20) | |

| MPL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (6) | |

| TN, n (%) | 7 (20) | 13 (15) | |

| Patients with additional mutations | |||

| None, n (%) | 21 (60) | 38 (44.2) | .17 |

| ≥2, n (%) | 6 (17.1) | 18 (20.9) | .82 |

| TET2, n (%) | 3 (8.6) | 16 (18.6) | .27 |

| DNMT3A, n (%) | 4 (11.4) | 9 (10.5) | 1 |

| ASXL1, n (%) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (3.5) | .63 |

| MPL (not W515), n (%) | 5 (14.3) | 3 (3.5) | .04 |

| Splicing, n (%) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (8.1) | .43 |

ELN, ≥60 years and/or history of thrombosis; high risk, (thrombosis history or age ≥60 years with JAK2 mutation); intermediate risk, (no thrombosis history, age ≥60 years, and JAK2-unmutated); LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; low risk, (no thrombosis history, age ≤60 years, and JAK2-mutated); r-IPSET, revised-IPSET; very low risk, (no thrombosis history, age ≤60 years, and JAK2-unmutated).

Molecular characteristics of 121 patients at diagnosis. (A) Distribution of driver mutations in the whole cohort. (B) Distribution of the number of additional clonal mutation per patient. (C) Number of additional mutations per gene in the whole cohort. The y-axis represents the total count of mutations detected in all patients, and the x-axis represents the 32 mutated genes ranked in order of frequency. (D) Distribution of variant allele frequency (VAF). Violin plots representing the distribution of allele burden for the most frequent mutation in JAK2V617F, CALR, TET2, and DNMT3A genes.

Molecular characteristics of 121 patients at diagnosis. (A) Distribution of driver mutations in the whole cohort. (B) Distribution of the number of additional clonal mutation per patient. (C) Number of additional mutations per gene in the whole cohort. The y-axis represents the total count of mutations detected in all patients, and the x-axis represents the 32 mutated genes ranked in order of frequency. (D) Distribution of variant allele frequency (VAF). Violin plots representing the distribution of allele burden for the most frequent mutation in JAK2V617F, CALR, TET2, and DNMT3A genes.

Response to treatment

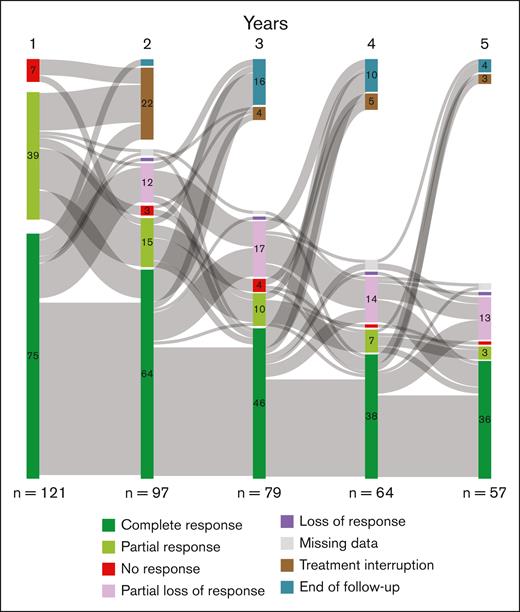

After 12 months of treatment with HU, 57% of patients achieved CR, 37% achieved PR, and 6% had no response while with peg-IFN; 74% of patients achieved CR, 20% PR, and 6% had no response. Herein, JAK2V617F was associated with more CR, and we also observed a faster response in JAK2V617F-mutated patients than CALR or triple negative cases (supplemental Figure 3). Seventeen patients discontinued their treatment during the first year of treatment, including 9 patients who were intolerant (4/35 [11.4%] on peg-IFN; and 5/86 [5.8%] on HU). Reasons for discontinuation and their response to second-line therapy are shown in supplemental Table 2. The evolutions of responses at each year during the first 5 years of treatment are represented by a Sankey diagram in Figure 2. During follow-up, the majority of patients who continued first-line therapy remained in CR (66%, 58%, 59%, and 65% at 2, 3, 4 and 5 years, respectively; Figure 2). At 5 years, a total of 34 patients (28%) discontinued first-line therapy, including 25 of 86 patients (29%) treated with HU and 9 of 35 patients (25.7%) treated with peg-IFN (supplemental Figure 4).

Evolution of response to treatment. Response assessment time points at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years are shown with transitions between each. The total height of the columns is proportional to the sample size. The number of patients receiving treatment is shown below the columns. This Sankey diagram represents the transition between 8 states: CR, PR, no response, partial loss of response, loss of response, missing data, treatment interruption, and end of follow-up.

Evolution of response to treatment. Response assessment time points at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years are shown with transitions between each. The total height of the columns is proportional to the sample size. The number of patients receiving treatment is shown below the columns. This Sankey diagram represents the transition between 8 states: CR, PR, no response, partial loss of response, loss of response, missing data, treatment interruption, and end of follow-up.

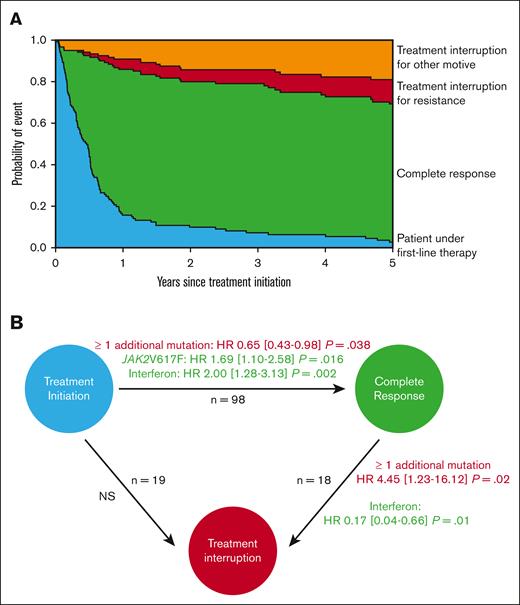

The global dynamics of CR and treatment discontinuation transitions were examined using a multistate model (Figure 3A). The presence of at least 1 additional mutation at diagnosis was associated with not achieving CR (hazard ratio [HR] and 95% confidence interval, 0.65, 0.43-0.98; P = .038), whereas a JAK2V617F mutation or a treatment with peg-IFN were associated with higher CR (HR, 1.69, 1.10-2.58; P = .016; HR, 2.00, 1.28-3.13; P = .002, respectively; Figure 3B). We restrained our analysis to CR and did not include association analyses with ORR because most patients (94%) achieved that level of response, and most patients with PR did not have stable response, with frequent oscillations between PR and loss of response. The presence of additional mutations was still associated with failure to achieve CR when triple-negative patients were excluded in the sensitivity analysis (supplemental Figure 5). Molecular follow-up of driver mutations, when available, according to treatment type and the presence of at least 1 additional mutation is described in supplemental Figure 6.

Variables associated with CR and treatment interruption. Predicted outcomes in patients on first-line therapy were accessed by a multistate model. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves representing 4 states and their transitions: treatment interruption because of resistance (red), interruption for other reasons (orange), patients in complete response (green), and patients on first-line therapy who did not reach any of the previous 3 states (blue). (B) Multistate model analysis with proportional Cox model results for each transition. Significant factors associated with state transition are indicated, with risk factors in red and protective factors in green. Treatment discontinuations due to resistance or other reasons were merged in the analysis. HRs are presented with their 95% confidence intervals. For each transition, the following factors were tested: age >60 years, driver mutation, ≥1 additional mutation, treatment type, previous thrombosis, and leukocyte counts, followed by a backward stepwise selection.

Variables associated with CR and treatment interruption. Predicted outcomes in patients on first-line therapy were accessed by a multistate model. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves representing 4 states and their transitions: treatment interruption because of resistance (red), interruption for other reasons (orange), patients in complete response (green), and patients on first-line therapy who did not reach any of the previous 3 states (blue). (B) Multistate model analysis with proportional Cox model results for each transition. Significant factors associated with state transition are indicated, with risk factors in red and protective factors in green. Treatment discontinuations due to resistance or other reasons were merged in the analysis. HRs are presented with their 95% confidence intervals. For each transition, the following factors were tested: age >60 years, driver mutation, ≥1 additional mutation, treatment type, previous thrombosis, and leukocyte counts, followed by a backward stepwise selection.

Patients treated with peg-IFN therapy responded earlier than those treated with HU, with a median time to achieving CR of 2.6 months for peg-IFN and 6.2 months for HU. Among patients who achieved CR, the presence of at least 1 additional mutation was associated with treatment interruption (HR, 4.45, 1.23-16.12; P = .02), whereas peg-IFN was associated with less treatment interruption (HR, 0.17, 0.04-0.66; P = .01). No variables were associated with the transition from “treatment initiation” to “interruption without achieving CR.”

Additional mutations and outcomes

The median follow-up was 8.4 and 6.1 years from treatment initiation until the last follow-up for patients treated with HU and peg-IFN, respectively. During follow-up, a thrombotic event occurred in 22 patients, leukemic evolution in 6 patients, myelofibrotic progression in 16 patients, and death in 15 patients. The presence of at least 1 additional mutation was not associated with a thrombotic risk during follow-up (P = .86; data not shown). There was more hematologic progression among non-CR patients at 12 months, without different overall survival (OS) (supplemental Figure 7). The number of additional mutations at diagnosis was associated with an increased risk of hematologic evolution (Figure 4A), even when TN patients were excluded from the analysis (supplemental Figure 8). This finding was confirmed in a multivariable analysis including the following variables: age (>60 years), gender, thrombocytosis (>700 G/L), leukocytosis (>11 G/L), previous thrombosis, and CR at 12 months. Indeed, 1 additional mutation (HR, 4.56, 1.07-19.4; P = .04) and the presence of at least 2 additional mutations (HR, 9.63, 2.20-42.1; P = .003) were associated with an increased risk of hematologic transformation (Figure 4B).

Hematologic-free survival according to mutational status. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve for hematologic evolution–free survival according to the number of additional mutations at diagnosis. The number of patients at risk for each group are shown in the table below the curves. (B) Forest plots representing the multivariable analysis including the following variables: age >60 years, gender, previous thrombosis, leukocytosis >11 G/L, and response at 12 months. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for hematologic evolution–free survival according to both the presence of additional mutations and the type of treatment received.

Hematologic-free survival according to mutational status. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve for hematologic evolution–free survival according to the number of additional mutations at diagnosis. The number of patients at risk for each group are shown in the table below the curves. (B) Forest plots representing the multivariable analysis including the following variables: age >60 years, gender, previous thrombosis, leukocytosis >11 G/L, and response at 12 months. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for hematologic evolution–free survival according to both the presence of additional mutations and the type of treatment received.

All patients were diagnosed with ET by the local multidisciplinary meeting and were then followed and treated as such. We tested the potential role of prefibrotic MF (preMF) and bone marrow biopsies from triple negative patients, and patients with a minor criterion for preMF (anemia, splenomegaly, or leukocytosis) were reviewed either by the French Bone Marrow Biopsy Study Group or by local pathologists. After careful review, 26 patients were reclassified as preMF. Additional mutations, but not preMF, were associated with hematologic transformation (supplemental Figure 9).

None of the patients receiving peg-IFN therapy progressed to MF, whereas 16 of 86 patients (19%) treated with HU developed secondary MF. We, therefore, analyzed hematologic transformation by stratifying according to additional mutations and treatment. Interestingly, the detrimental association of additional mutations with hematologic evolution appeared to be preponderant in HU-treated patients but not in peg-IFN treated patients (P = .005; Figure 4C).

Finally, the number of additional mutations was not associated with OS (supplemental Figure 10), and only age was associated with a risk of death on multivariate analysis (HR, 1.09, 1.02-1.16; P = .008; data not shown).

Discussion

Patients with ET at risk of thrombosis require cytoreductive therapy to prevent these complications. In these patients, resistance or intolerance to first-line therapy has been associated with worse outcomes. More specifically, this situation is associated with a higher rate of transformation to MF and a higher risk of death.19 To date, no marker at diagnosis has been identified to predict treatment response. It would therefore be of interest to identify which patients at diagnosis will eventually have resistance to therapy, to personalize choice of treatment and monitoring during the follow-up. Here, we present data from a real-life cohort of first-line–treated patients with ET with comprehensive characterization of the mutational landscape by high-throughput sequencing.

We observed a high level of response to first-line treatment, with 57% achieving CR with HU and 74% with peg-IFN and a global ORR of 94% at 1 year of treatment. The only randomized trial comparing HU and peg-IFN as first-line treatment in ET found lower rates of CR at 12 months, with 45% for HU (ORR, 71%) and 44% for peg-IFN (ORR, 69%).32 Of note, these results were from intention-to-treat analysis, whereas our study included only patients who received treatment. However, our results are consistent with those of Desterro et al, who reported a real-life experience in the United Kingdom of interferon therapy in ET.33 They observed CR in 75% of cases and PR (defined as platelet count <700 ×109/L in their study) in 25% of cases. In a national registry from Spain, Alvarez-Larrán et al reported 1104 patients with ET first-line treated (88% with HU), with 69% achieving CR, 26% achieving PR, and 5% no response.34

In our study, patients receiving peg-IFN therapy had more favorable outcomes with more CR and fewer treatment interruptions after CR. We observed a shorter time to response with peg-IFN than HU (2.6 vs 6.17 months). In the UK cohort, the median time to achieving CR with peg-IFN was 6.5 months with ∼50% of patients not in first-line therapy.33 In the Spanish cohort, the median time to CR with HU varied by driver mutation: 5.6 months, 12.7 months, 14.2 months, and 27 months for patients with JAK2, TN, MPL, and CALR driver mutations, respectively.34 Because initial dosing of HU and timing of dose escalation were not standardized, we may speculate that physicians were not as hasty to achieve CR in older patients receiving HU.

In MPN, additional mutations have been mainly studied for their role in prognostic stratification. However, there are very few studies on their association with treatment response in ET. In the study reported by Quintás-Cardama et al, in a cohort consisting of 43 patients with polycythemia vera and 39 with ET treated with peg-IFN, those who failed to achieve complete molecular response had a higher frequency of additional mutations (56%) than those who achieved complete molecular response (30%).27 In the cohort reported by Verger et al, including 31 patients with ET with CALR mutations on peg-IFN therapy, all patients achieving a complete or partial molecular response had no additional mutations.28 Here, we demonstrated in multivariate analysis that the presence of additional mutations was a risk factor for not achieving CR not only for patients treated with peg-IFN but also in those treated with HU.

Finally, we found that the number of additional mutations was associated with hematologic transformation to either MF or acute myeloid leukemia. The prognostic impact of additional mutations in MPN was mostly described in MF, but previous studies also reported an impact of the number of additional mutations on hematologic evolutions35 or overall survival.22 Having additional mutation is common in ET (51% in this study). Our results also suggested that peg-IFN treatment may mitigate the deleterious impact of additional mutations. This could reflect the ability of peg-IFN to exhaust some mutated clones.18,36 Similarly to our results, Desterro et al observed no hematologic evolution in 53 patients with a median follow-up of 9 years.33 This provides further support for the use of peg-IFN to limit the risk of progression.37

Several limitations of our study must be acknowledged. This is a retrospective, monocentric, observational analysis of patients who received treatment for ET, largely as part of standard of care, precluding us from drawing conclusions on treatment efficacy. Although we included all unbalanced variables between HU and peg-INF groups in our multivariate models, we cannot exclude that there may be some residual bias. Because molecular analysis was performed at the time of diagnosis but a small proportion of patients started their therapy later (9% after 18 months of follow-up), we cannot exclude that some patients may have acquired additional mutations at that time. Based on previous studies, we assumed that the molecular landscape of MPN in chronic phase is stable, with only 2% of patients acquiring new mutations each year.35,38 Future studies are needed to evaluate whether repeated molecular assessment in therapeutic decision-making could be of interest. We considered all additional mutations regardless of the mutated gene, but some specific mutations may not be equally associated to treatment response. In a sensitivity analysis, we found the same detrimental effect on CR for mutations in the TET2 gene compared with other additional mutations (supplemental Figure 11).

In conclusion, our results suggest that the presence of at least 1 additional mutation at diagnosis, affecting approximately half of patients with ET, is associated with failure to achieve CR and is also associated with an increased risk of hematologic evolution. Because treatment resistance has been described as associated with hematologic evolution, we speculate that additional mutations are the causal factors associated with both events. Larger multicenter cohorts and external validation cohorts are needed to confirm this association.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Biological Ressources Center of Angers (BB-0033-3038 CRB du CHU d'Angers) for providing high quality samples.

This work was supported in part by the French National Institute of Cancer (FIMBANK, Institut National du Cancer [INCa] bases de données clinico-biologiques BCB 2013 and 2022).

Authorship

Contribution: C.M. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; L.C., S.L., and A.M. provided clinical and biological data and analyzed mutational profiles; S.B., B.P., and M.C.C. analyzed bone-marrow biopsies; F.B. provided clinical data; J.A. performed bioinformatic analyses; R.J.-C. and A.M. performed next-generation sequencing analysis; J.R. supervised statistical analyses; M.H.-B. provided clinical data and wrote the manuscript; V.U. wrote the manuscript; C.O. and D.L.P. conceived the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Damien Luque Paz, Université Angers, Nantes Université, CHU Angers, INSERM, CNRS, CRCI2NA, 4 Rue Larrey, 49933 Angers Cedex 9, France; email: damien.luquepaz@chu-angers.fr.

References

Author notes

C.O. and D.L.P. contributed equally to this work.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Damien Luque Paz (damien.luquepaz@chu-angers.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.