Drs. Ajioka and Prchal indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.

Du X, She E, Gelbart T, et al. The serine protease TMPRSS6 is required to sense iron deficiency. Science. 2008;320:1088-92.

Iron is an essential element, but because of its potential toxicity, free iron levels must be tightly regulated. Regulation is mediated primarily via the duodenal cells and macrophages that control plasma iron levels by the rate at which they export iron. Much of the regulation can be explained through the peptide hepcidin, whose action is to inhibit cellular iron export. Hepcidin is primarily synthesized in the liver and is induced by elevated hepatic iron and inflammation. In defining the cause of anemia in the "mask" mouse, Du and colleagues uncovered a major inhibitory pathway of hepcidin expression. This discovery leads to the conclusion that iron balance is maintained by the opposing forces of induction and inhibition of hepcidin.

The discovery of the 25-amino-acid peptide hepcidin explains much about iron homeostasis.There is a direct correlation between hepatic iron content and hepcidin expression. Hepcidin binds the plasma membrane, iron export protein, ferroportin, inducing its internalization and degradation, thus down-regulating iron export by the enterocyte and macrophage. Hepcidin is also an acute-phase reactant responding to both IL-1α and IL-6. Separate iron- and inflammation-responsive elements have been demonstrated in the hepcidin promoter region. This provides a simple model for the regulation of plasma iron levels: Elevated iron stores or inflammatory stimuli induce hepcidin synthesis, which, in turn, reduces plasma iron levels and protects tissue from pro-oxidant conditions and restricts availability of iron to pathogens.

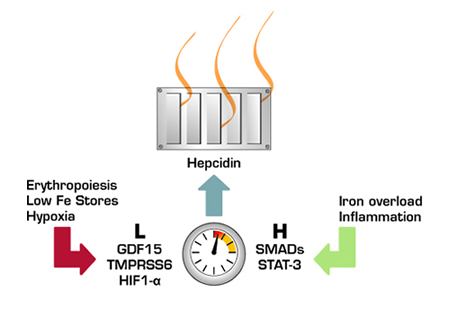

Iron Homeostasis is Maintained Through a Balance Between Stimulatory and Inhibitory Signals to Hepcidin. The hepcidin thermostat is up-regulated by iron overload and inflammation and down-regulated by anemia/erythropoiesis, low iron stores, and hypoxia.

Iron Homeostasis is Maintained Through a Balance Between Stimulatory and Inhibitory Signals to Hepcidin. The hepcidin thermostat is up-regulated by iron overload and inflammation and down-regulated by anemia/erythropoiesis, low iron stores, and hypoxia.

Low iron status results in increased dietary iron absorption and macrophage iron export. This response does not appear to be a result of lack of hepcidin induction, as hepcidin levels are reduced below baseline during active erythropoiesis. Recently, GDF15, which is highly expressed in the plasma of patients with β-thalassemia, was shown to suppress transcription of hepcidin. In the May issue of Science, Du and coworkers characterized a mouse with a nitrosourea-induced mutation that created a phenotype of anemia, infertility in females, and an unusual distribution of fur. The mutant was dubbed "mask" due to hair loss over the entire body with exception of the face. Maintenance on a high-iron diet resulted in restoration of hair growth and fertility. A critical observation was that, despite their anemia, "mask" mice had high hepcidin transcript levels. The mutated gene was identified as the transmembrane serine protease Tmprss6 that is primarily expressed in the liver. A BAC Tmprss6 transgene reversed the phenotype in mutant mice. Site-directed mutagenesis of Tmprss6 leads to loss of proteolytic activity and increased hepcidin due to loss of hepcidin-inhibitory activity. In rapid succession, several laboratories have verified the central importance of this gene in human iron homeostasis and reported several Tmprss6 mutants in families with microcytic anemias, poor response to iron therapy, and high hepcidin levels.(1-4)

In Brief

Hepcidin inhibition was shown to occur through a proximal repressor element in the hepcidin promoter. The authors further present evidence that the ectodomain is involved in signal suppression in the absence of stimulus, while the cytoplasmic domain is involved in signal transduction. Whether Tmprss6, HIF1-α, and GDF15 are part of a common mechanism for hepcidin suppression remains to be determined. Nevertheless, characterization of Tmprss6 has unmasked yet another layer of the mystery of iron homeostasis and will guide future research in defining the pathway of hepcidin inhibition.