The use of allogeneic transplantation is largely shaped by the availability of less toxic but effective therapies. Thus, while "curative" in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), upfront tranplant has been displaced by imatinib and now is only employed in cases of refractory or advanced-phase disease. However, for secondary myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), attempts to use effective chemotherapy have been unsuccessful, and transplantation may offer the only hope. Two recent studies help us define the efficacy of transplant for these two diseases.

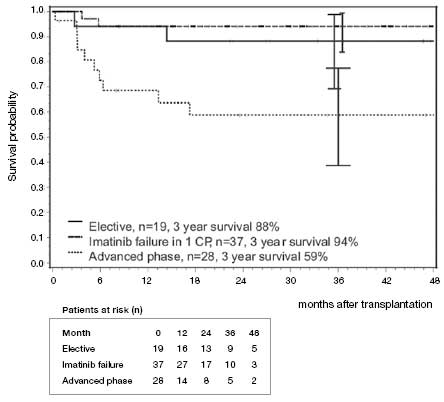

Results From German CML Study IV on 84 Patients who Received a Matched Allogeneic Transplant Because of Either a High-Disease Risk Score at Diagnosis, Imatinib Failure, or Progressive Disease. Probability of overall survival after allogeneic transplant is shown in the top figure. The box on the bottom shows a matched pair analysis comparing chronic-phase patients receiving transplantation compared to patients receiving imatinib therapy.This figure was originally published in Blood.

Results From German CML Study IV on 84 Patients who Received a Matched Allogeneic Transplant Because of Either a High-Disease Risk Score at Diagnosis, Imatinib Failure, or Progressive Disease. Probability of overall survival after allogeneic transplant is shown in the top figure. The box on the bottom shows a matched pair analysis comparing chronic-phase patients receiving transplantation compared to patients receiving imatinib therapy.This figure was originally published in Blood.

Imatinib is remarkably effective in chronic-phase CML; most patients who remain on the drug will obtain a complete cytogenetic remission and will have an excellent diseasefree survival. However, some studies suggest that imatinib is less effective in the general community than in the controlled setting of clinical trials,1 and in one large trial, 40 percent of patients stopped therapy,2 most often for toxicity or lack of efficacy. Secondary therapy with next-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can salvage approximately half of those patients, leaving a moderately large niche for transplantation. The German CML Study IV recently reported their results on 84 patients who received a matched allogeneic transplant because of either a high-disease risk score at diagnosis, imatinib failure, or progressive disease. The three-year survival was excellent, at 91 percent for chronic-phase cases and 59 percent for advanced-phase patients (Figure 1). Moreover, nearly 90 percent of the survivors were in complete molecular remission. Regimen-related mortality was only 8 percent. A matched comparison of chronic-phase patients who received transplant compared to imatinib showed no difference in survival at the three-year mark. These impressive results suggest that in the modern era, with better conditioning regimens, patient selection, and supportive care, transplantation should be considered early in patients with a poor response to initial TKI therapy.

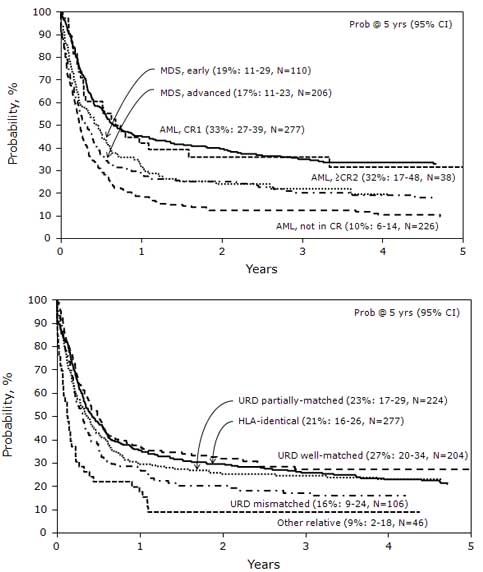

Probability of overall survival after allogeneic transplant for t-MDS (top panel) and t-AML (bottom panel), based on risk score.This figure was originally published in Blood.

Probability of overall survival after allogeneic transplant for t-MDS (top panel) and t-AML (bottom panel), based on risk score.This figure was originally published in Blood.

While the role of transplantation has properly diminished in CML, a different dynamic exists for secondary MDS, which is exceedingly resistant to chemotherapy approaches. A large study by the Center for International Bone Marrow Transplant Research examined the role of transplantation in treatment-related MDS (323 cases) and AML (545 cases). Perhaps owing to the heavy pretreatment of these patients compared to the CML experience cited above, the regimen-related mortality after one year was 41 percent and at five years was 48 percent. The relapse and overall survival rates at five years were 31 and 22 percent. The authors developed a risk model, using age (> 35 years), poor-risk cytogenetics, lack of remission, and the use of a poorly HLAmatched donor, and showed that survival mapped closely to the accumulated score. Patients with no points had a five-year survival of 50 percent while only 4 percent of those with the most points (four) survived five years (Figure 2). Thus, though the aggregate outlook of these patients following transplant is poor, certain subsets enjoy a reasonable chance at a potentially curative therapy.

In Brief

As clinicians, it is important to consider that the success of transplantation is largely an issue of appropriate timing. Finding a donor, be it related or unrelated, takes time, sometimes several months. Thus, planning is key. For CML, one should not wait for a patient to be resistant to all TKI therapy before starting a donor search, as these patients are more likely to progress to advanced-phase disease, where the efficacy of transplantation is greatly diminished. For therapy-related MDS and AML, HLA typing and donor search should be instituted as soon as possible. Moreover, alternative sources, such as umbilical cord stem cells, can be considered for patients for whom a donor is not available.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Radich indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.