Knowledge of the blast phenotype in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) would be valuable, as in other malignancies, but remains sparse. This is mainly because MDS blasts are a minor population in clinical samples, making analysis difficult. Thus, for this blast phenotype study, we prepared blast-rich specimens (using a new density centrifugation reagent for harvesting blasts) from blood and marrow samples of 95 patients with various MDS subtypes and 21 patients with acute leukemia transformed from MDS (AL-MDS). Flow cytometry revealed that a high proportion of the enriched blast cells (EBCs) from almost all patients showed an immunophenotype of committed myeloid precursors (CD34+CD38+HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+), regardless of the disease subtype. The cytochemical reaction for myeloperoxidase was negative in 58% of the cases. Thus, the EBC phenotype is more immature in MDS than in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. MDS EBCs often coexpressed stem cell antigens and late-stage myeloid antigens asynchronously, but rarely expressed T- and B-lymphoid cell–specific antigens. Markers for myeloid cell maturation (CD10 and CD15) were more prevalent on EBCs from low-risk MDS (refractory anemia [RA] and RA with ringed sideroblasts), whereas markers for myeloid cell immaturity (CD7 and CD117) were more prevalent on EBCs from high-risk MDS (chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, RA with excess blasts [RAEB], and RAEB in transformation) and AL-MDS. A shift to a more immature phenotype of EBCs, accompanying disease progression, was also documented by sequential phenotyping of the same patients. Further, CD7 positivity of EBCs was an independent variable for a poor prognosis in MDS. These data represent new, valuable information regarding MDS.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a malignant disorder of hematopoietic progenitors in which the bone marrow (BM) is composed of clonal hematopoietic cells showing various degrees of differentiation in each case.1-3 The French-American-British (FAB) cooperative group proposed 5 subgroups of MDS based mainly on the percentage of blasts in the BM and peripheral blood (PB), that is, refractory anemia (RA), RA with ringed sideroblasts (RARS), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), RA with excess blasts (RAEB), and RAEB in transformation (RAEB-t).4 Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a classification for MDS,5 but its biologic and clinical relevance has been thrown into question by subsequent data.6,7 MDS usually shows cytopenia, mainly due to early death of partially or fully differentiated hematopoietic cells and insufficient differentiation capacity of the progenitors to mature blood cells. The prognosis of MDS, which differs among FAB subtypes and is more accurately predicted by the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), is extremely poor.8 Manifestations caused by cytopenia and transformation to acute leukemia (AL) due to further loss of the ability of clonal cells to differentiate are the major causes of death in MDS.

Immunophenotype data for whole myeloid cells of various maturity, erythroblasts, and megakaryocytes in MDS have been reported.9 However, contrary to de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML), few phenotypic data have been compiled regarding MDS blasts. One of the main reasons for this is that MDS blasts are not predominant cells in the BM and PB, making reliable analysis of blasts difficult. In our own experience, reliable immunophenotype data for MDS blasts were obtained for only a fraction of MDS cases by flow cytometry (FCM). Hitherto, the available data on the MDS blast phenotype are for blasts of acute leukemia transformed from MDS (AL-MDS)10and blasts before leukemic transformation,11,12 the latter of which were able to be analyzed only by immunocytochemistry and immunohistochemistry. Regarding the latter case, due to weaknesses of the applied techniques, the accuracy and objectivity of the data were not definitive and the number of antibodies used was small. Phenotypic data for MDS blasts would be useful for the following reasons. First, the phenotype of MDS blasts would help in the development and application of therapeutic agents for targeting cell surface antigens, like the anti-CD33 calicheamicin conjugate and inhibitors of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) for de novo AML.13 14Second, knowledge of the blast phenotype could help to predict the outcome of patients. Third, blast phenotype data could be used to subclassify MDS and distinguish between MDS and de novo AML. To date the latter has been done arbitrarily on the basis of the percentage of blasts in the BM and PB, which is not biologically relevant.

One of the present authors developed a method, using metrizamide density centrifugation, for harvesting blasts of high purity and high recovery from PB and BM of patients with MDS.15 Based on this method, a stable density centrifugation reagent for reproducibly harvesting viable blasts was developed.16 This is a novel reagent not containing Ficoll-Hypaque, Percoll, or albumin. Regarding MDS blasts, which often exist as a minor cell population in samples, there had been no reliable data (such as their pattern on the CD45 versus side scatter [SSC] display of FCM) for gating of blasts by FCM. Therefore, in this study, we used that new density centrifugation reagent to obtain blast-rich specimens from patients with MDS and AL-MDS, which allowed reliable blast gating to determine the phenotype of enriched blast cells (EBCs) in most of the patients at diagnosis (n = 116). We also analyzed the EBC phenotype after disease progression in some patients. This is the first report to present the detailed phenotypic features of MDS blasts and their clinical significance.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Patients with MDS and AL-MDS who had been diagnosed and treated at the 7 participating institutions during 1998-2000 were the subjects of this study. Patients who had previously undergone cytotoxic chemotherapy and those with secondary MDS were excluded. Disease diagnoses were made according to the FAB criteria.4,17Cytogenetic analyses were performed using standard G-banding with trypsin-Giemsa staining. Karyotypes were interpreted using the International System for Cytogenetic Nomenclature criteria.18 The IPSS of each MDS patient was determined according to the definition reported by Greenberg et al.8

Cell preparation

Heparinized aspirated BM cells were obtained for clinical diagnosis, and soon after the diagnosis heparinized PB was obtained from the patients. PB samples that contained at least 0.25% blasts were used. The volume of aspirated BM cells used for harvesting blasts was at least 4 mL in RA and RARS cases and at least 1.5 mL in cases with other disease subtypes. Heparinized aspirated BM cells were also obtained from healthy volunteers. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nippon Medical School, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. A density gradient centrifugation reagent for harvesting blasts (Blastretriever [BR]) was kindly provided by Japan Immunoresearch Laboratories (Takasaki, Japan). Blast harvesting from the heparinized samples was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. That is, up to 2.5 mL of the sample (unmanipulated PB or BM cells diluted 3-fold with RPMI 1640 medium) was layered onto 2.5 mL of the BR solution in a glass tube (inner diameter: 14 mm) and spun at 550g for 10 minutes at room temperature. The low-density cells were taken from the BR interface, washed with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, and used for FCM and cytospin preparations. The cell differential was determined from Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations. In some experiments, cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion, and the cell count was determined with a hemocytometer.

FCM and cytochemistry

Immunophenotyping was performed by 3-color FCM, in which EBCs and other cell populations were gated by a CD45-gating method.19 20 In brief, the cells were stained with anti-CD45 antibody labeled with peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and pairs of antibodies conjugated with either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE). These antibodies were directed to CD3, CD5, CD8, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD25, CD34, HLA-DR (FITC-conjugated; Becton Dickinson), CD4, CD11b, CD13, CD14, CD34 (PE-conjugated; Becton Dickinson), CD2, CD7, CD38 (FITC-conjugated; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), CD20, CD33, CD56 (PE-conjugated; Pharmingen), CD10, CD117, and glycophorin A (PE-conjugated; Coulter-Immunotech, Hialeah, FL). Single-labeled cells were used to compensate for fluorescence emission overlap of each fluorochrome into inappropriate channels. Isotype-matched negative controls were used in all assays. At least 10 000 events were acquired for most samples. Expression of each antigen was regarded as positive when at least 20% of gated cells were more fluorescent than the negative control. Analysis was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analyses

Differences between 2 groups of data of continuous variables were analyzed by Student t test. Differences in categorical variables were evaluated using the χ2 test. The duration of overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of diagnosis (almost identical to the date of the blast phenotyping) until death. The duration of transformation-free survival (TFS) was calculated from the time of diagnosis until the date of transformation to AL. Patients dying from any cause without developing AL were treated as censored data regarding the date of death in the TFS analysis. Patients who underwent stem cell transplantation (SCT) or who were lost to follow-up were also censored regarding the date of SCT or the last follow-up in both the OS and TFS analyses. Survival curves were obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test or, when applicable, by the test for trend. Multivariate analysis was performed by Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. P > .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Validity of the use of BR density centrifugation

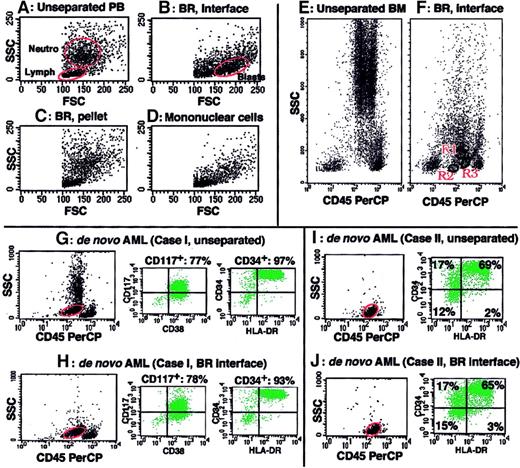

Figure 1 presents an example of blast enrichment by BR density centrifugation. When PB containing 1.5% blasts (Figure 1A) was obtained from an MDS patient and subjected to BR density centrifugation, nucleated cells were separated into 2 fractions, that is, the BR interface and BR precipitate. Whereas erythrocytes were exclusively in the BR precipitate, blasts were recovered in the BR interface with high purity (Figure 1B) but were negligible in the BR precipitate (Figure 1C). Reagents for mononuclear cell isolation, such as Ficoll-Paque, could not sufficiently enrich blasts from the same PB sample (Figure 1D). When aspirated BM cells from healthy volunteers (n = 5) were subjected to BR density centrifugation and analyzed by FCM, both myeloblasts (CD45lowCD34+CD13+CD33+) and 2 types of B-cell precursors (stage I [CD45lowCD34+CD10+CD19+CD20±] and stage II [CD45lowCD34−CD10+CD19+CD20+] immature B cells), which were reported to exist in normal BM as very minor populations,21 were detected on the CD45 versus SSC display of cells in the BR interface (a representative example is shown in Figure 1F). These cell populations were not detected on the same display for cells in the BR precipitate (data not shown). We then confirmed that the results of immunophenotyping and cytochemistry of blasts did not differ between unprocessed blasts and blasts obtained by BR density centrifugation for all the examined samples (n = 64) that had been obtained from acute lymphocytic leukemia, AML, and RAEB-t cases (representative immunophenotyping of blasts in unprocessed samples and blasts separated by BR density centrifugation from the same samples are shown in Figure 1G-J). The recovery of blasts after BR density centrifugation (the number of blasts in the BR interface divided by the number of blasts in the unseparated sample) was determined for 27 of the above 64 samples and showed a mean value of 69.6% ± 12.5%. The viability of separated cells was at least 98%, with well-preserved morphology. Based on these findings, we decided to use BR density centrifugation to enrich MDS blasts for characterization.

BR density centrifugation enriches blasts without altering immunophenotype data of blasts.

(A-D) SSC versus FSC display of cell fractions of PB from an MDS patient. PB containing 1.5% blasts (A) was subjected to BR density centrifugation (B-C) or Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation (D). Blasts were markedly enriched in the BR interface (B) but not recovered in the BR precipitate (C). Blast enrichment by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation was minimal (D). Blast percentages determined in Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations by examining 100 cells were 63%, 0%, and 5% for panels B, C, and D, respectively. Circles marked as Neutro, Lymph, and Blasts in panels A and B indicate neutrophil, lymphocyte, and blast populations, respectively. (E-F) CD45 versus SSC display of normal BM cells before (E) and after BR density centrifugation (F, the BR interface). Immunophenotyping showed that the predominant cells in R1 were immature myeloid cells (CD34 57%, CD13 49%, CD33 50%) with minor contamination by immature B cells (CD10 22%, CD19 20%), the cells in R2 were stage I immature B cells (CD34 57%, CD10 75%, CD19 87%, CD20 27%, CD13 and CD33 < 15%), and the cells in R3 were stage II immature B cells (CD34 8%, CD10 67%, CD19 71%, CD20 56%, CD13 and CD33 < 15%). (G-J) Samples from 2 de novo AML cases (cases I and II) were subjected to blast immunophenotyping before (G,I) and after BR density centrifugation (H,J). The circles on the CD45 versus SSC display indicate gates for blast immunophenotyping. Immunophenotype data remained unchanged after BR density centrifugation.

BR density centrifugation enriches blasts without altering immunophenotype data of blasts.

(A-D) SSC versus FSC display of cell fractions of PB from an MDS patient. PB containing 1.5% blasts (A) was subjected to BR density centrifugation (B-C) or Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation (D). Blasts were markedly enriched in the BR interface (B) but not recovered in the BR precipitate (C). Blast enrichment by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation was minimal (D). Blast percentages determined in Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations by examining 100 cells were 63%, 0%, and 5% for panels B, C, and D, respectively. Circles marked as Neutro, Lymph, and Blasts in panels A and B indicate neutrophil, lymphocyte, and blast populations, respectively. (E-F) CD45 versus SSC display of normal BM cells before (E) and after BR density centrifugation (F, the BR interface). Immunophenotyping showed that the predominant cells in R1 were immature myeloid cells (CD34 57%, CD13 49%, CD33 50%) with minor contamination by immature B cells (CD10 22%, CD19 20%), the cells in R2 were stage I immature B cells (CD34 57%, CD10 75%, CD19 87%, CD20 27%, CD13 and CD33 < 15%), and the cells in R3 were stage II immature B cells (CD34 8%, CD10 67%, CD19 71%, CD20 56%, CD13 and CD33 < 15%). (G-J) Samples from 2 de novo AML cases (cases I and II) were subjected to blast immunophenotyping before (G,I) and after BR density centrifugation (H,J). The circles on the CD45 versus SSC display indicate gates for blast immunophenotyping. Immunophenotype data remained unchanged after BR density centrifugation.

Blast enrichment by BR centrifugation from 143 samples

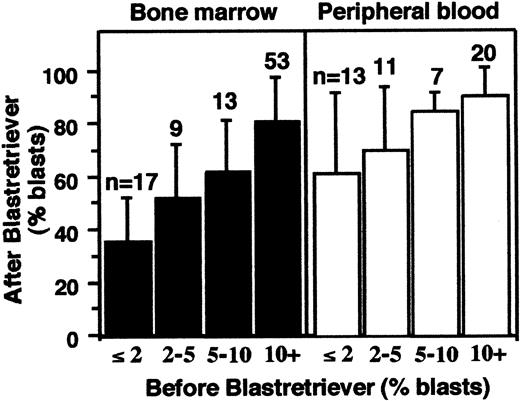

Cell samples (n = 143) from patients with MDS and AL-MDS were subjected to BR density centrifugation, and the blast fraction (the BR interface) was collected for subsequent analyses. Figure2 shows the correlation between the percentage of blasts in these samples before and after the centrifugation. Blast enrichment was achieved for both the aspirated BM cells and PB and was more efficient in the latter. The smallest percentage of blasts in these 143 samples before centrifugation was 0.25%, which was observed in 3 PB samples. The percentages of blasts after the BR density centrifugation of these 3 samples were 44%, 46%, and 96%.

Blast enrichment of 143 samples.

Aspirated BM cells (left) and PB (right) were separated by BR density centrifugation. The x-axis is the percent blasts before separation; y-axis is the percent blasts after separation (means ± SD).

Blast enrichment of 143 samples.

Aspirated BM cells (left) and PB (right) were separated by BR density centrifugation. The x-axis is the percent blasts before separation; y-axis is the percent blasts after separation (means ± SD).

Flow cytometric gating of blasts enriched by BR centrifugation

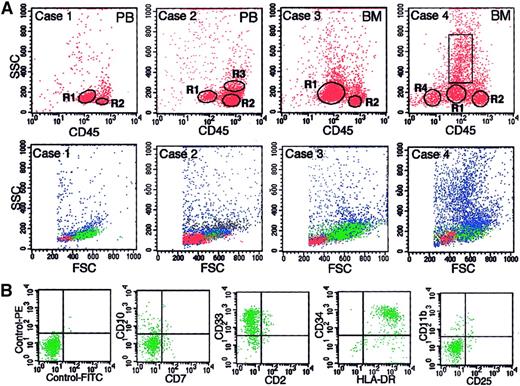

The BR density centrifugation enriched blasts as well as simplified cell compositions in the harvested cell fractions; thus, reliable gating of blasts by FCM was possible for most samples. Representative examples of this gating are shown in Figure3A, in which a gate for blasts is marked as R1, and the percentages of blasts determined in Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations are shown in the legend. Cases 1 and 3 of Figure 3A are examples of the cell fractions in which blasts are predominant. Minor contamination by other cells, most of which were lymphocytes (R2), was able to be easily excluded by gating on the CD45 versus SSC display. Case 2 is an example of a cell fraction in which blasts are a minor population. Because the cell composition of this case is simple (blasts, lymphocytes [R2], and monocytes [R3]), the blasts were easily gated. Each gated cell population in cases 1 to 3 showed a typical cytogram on the forward scatter (FSC) versus SSC display (lower panels of Figure 3A) and a typical antigen profile for each cell population (data not shown). Case 4 of Figure 3A is the most complicated case. The cell fraction of this patient, whose diagnosis was RA, had a relatively diverse cell composition compared with the other cases but consisted of 3 kinds of cell cluster (blasts, lymphocytes [R2], and erythroid cells [R4]) and myeloid cells, other than myeloblasts, in various stages of maturation (cells in the rectangle) on the CD45 versus SSC display. Regarding case 4, part of the flow cytometric immunophenotyping for blasts (cells in R1) is shown in Figure 3B, and the cardinal data of the antigen profiles for 4 gated cell populations are shown in Table 1. The cells in R1 in this case were confirmed to be blasts with a myeloid phenotype on the basis of the following findings. (1) Expression of CD34 is a definitive indicator of blasts, as is the expression of HLA-DR without CD11b on moderately CD45+cells.21 The cells in R1 in this case met both of these criteria. (2) The cells in R1 showed a typical cytogram of blasts on both FSC versus SSC and CD45 versus SSC displays. (3) The percentage of cells gated by R1 was compatible with the percentage of blasts determined in cytospin preparations.

Representative examples of gating of blasts by 3-color FCM.

(A) Data are shown for 4 cases for which the BR interface contained various percentages of blasts. The percentages of blasts determined in cytospin preparations were 96%, 17%, 66%, and 22% for cases 1 through 4, respectively. The samples subjected to BR density centrifugation were PB for cases 1 and 2 and BM cells for cases 3 and 4. The upper panels are CD45 versus SSC displays in which R1, R2, R3, and R4 are gates for blasts, lymphocytes, monocytes, and erythroid cells, respectively. The rectangle in case 4 shows the gate for myeloid cells other than myeloblasts. The gated cells in R1 through R4 are shown as green, red, black, and yellow dots, respectively, in the lower panels, which show the FSC versus SSC displays for each case. (B) Examples of antigen expression analysis of blasts (cells in R1) by FCM for case 4.

Representative examples of gating of blasts by 3-color FCM.

(A) Data are shown for 4 cases for which the BR interface contained various percentages of blasts. The percentages of blasts determined in cytospin preparations were 96%, 17%, 66%, and 22% for cases 1 through 4, respectively. The samples subjected to BR density centrifugation were PB for cases 1 and 2 and BM cells for cases 3 and 4. The upper panels are CD45 versus SSC displays in which R1, R2, R3, and R4 are gates for blasts, lymphocytes, monocytes, and erythroid cells, respectively. The rectangle in case 4 shows the gate for myeloid cells other than myeloblasts. The gated cells in R1 through R4 are shown as green, red, black, and yellow dots, respectively, in the lower panels, which show the FSC versus SSC displays for each case. (B) Examples of antigen expression analysis of blasts (cells in R1) by FCM for case 4.

Similar to these examples, the reliability of flow cytometric gating of blasts was carefully checked for all 143 samples, and 6 samples were excluded from the subsequent analyses (3 samples due to insufficient cell number and 3 samples due to inaccurate gating of the blasts). Thus, data for 137 samples from 116 cases (both PB and BM samples for 21 cases) were analyzed. Table 2 shows the characteristics of these 116 cases. Because a larger volume of aspirated BM cells was needed for harvesting blasts from RA and RARS cases, the number of these cases was relatively small compared with the other disease subtypes.

Immunophenotyping and cytochemistry of EBCs from 116 cases

The data for EBCs from 116 cases are summarized in Tables3 and 4. B-cell precursors, which can be detected in normal BM samples after BR density centrifugation, were detected in 2 RA cases and 1 RAEB case among the subjects whose BM cells were analyzed (n = 79). For these 3 cases, the data of gated blasts other than B-cell precursors are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The data for PB and BM samples from the same subjects (n = 21) did not differ. We also show the immunophenotype of de novo AML blasts prepared by BR density centrifugation for comparison (Table5).

The MDS EBCs of almost all cases had the phenotype of a committed myeloid precursor (CD34+CD38+HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+; Table 3). Cases positive for CD34, CD38, HLA-DR, CD13, and CD33 were 112 of 116 cases (positive cases among total cases examined, 97%), 108 of 111 cases (97%), 116 of 116 cases (100%), 114 of 114 cases (100%), and 114 of 116 cases (98%), respectively. The percentages of EBCs positive for CD34, CD38, HLA-DR, CD13, and CD33 (mean ± SD of data from the positive cases) were 81.6% ± 18.9%, 88.0% ± 14.1%, 90.5% ± 13.0%, 84.3% ± 16.6%, and 76.5% ± 20.5%, respectively. All 116 cases were positive for CD13 or CD33 or both. Three cases had a CD34+CD38− phenotype, and all were HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+. There were 4 CD34− cases, and all were CD38+HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+.

CD117, which is expressed on a subset of hematopoietic progenitors and mast cells in normal hematopoiesis, was expressed in 73 of 114 cases (64%). MPO was negative in 63 of 108 cases (58%). The high prevalence of CD34+ cases and MPO− cases in MDS differs from the data of de novo AML (see “Discussion”). During normal neutrophil maturation, CD15 and CD11b begin to appear on promyelocytes and myelocytes, respectively, and continue their expression to mature neutrophils.23 These antigens were expressed in 73 of 114 cases (64%) and 53 of 111 cases (48%), respectively. Such asynchronous expression of antigens, that is, expression of both stem cell antigens and maturation antigens, is well known in de novo AML, as shown in Table 5 and reported by others.22 24

Table 4 shows the expression data for lymphoid lineage–associated antigens. Among the T cell–associated antigens, no cases were CD3+ or CD8+, and 3 cases were CD2+or CD5+. Compared with these antigens, CD4 and CD7 are less restricted to lymphoid cells in normal hematopoiesis; that is, the former is expressed on monocytes, and the latter is expressed on a fraction of CD34+ myeloid progenitors and proposed as a marker of immaturity in myeloid cells (see “Discussion”). EBCs expressed CD4 and CD7 in 54 of 114 cases (47%) and 40 of 116 cases (34%), respectively. Among B cell–associated antigens, no cases were CD19+ or CD20+ or both. Expression of CD10, which is detected on B-cell precursors and mature neutrophils in normal hematopoiesis,25 was observed in 22 of 116 cases (19%). Regarding natural killer (NK) cell–associated antigens, 31 of 116 cases (27%) were CD56+. Expression of CD16, which is observed on NK cells, metamyelocytes, and mature neutrophils in normal hematopoiesis,23 was negative for all examined cases.

When the disease subtype was classified as low-risk MDS (RA and RARS), high-risk MDS (CMML, RAEB, and RAEB-t), or AL-MDS, the proportion of cases positive for CD7, CD10, CD15, and CD117 differed significantly among them (Table 6), whereas the other data presented in Tables 3 and 4 did not. Markers for immaturity of myeloid cells (CD7 and CD117) were more prevalent in high-risk MDS and AL-MDS, whereas markers for maturation of myeloid cells (CD10 and CD15) were more prevalent in low-risk MDS. In particular, none of 23 low-risk cases were CD7+, and almost all low-risk MDS cases (21 of 22 cases) were CD15+. We then investigated whether the difference in immunophenotype between MDS subtypes occurs during disease progression of individual cases. For this purpose we assumed that, among the 4 antigens presented in Table 6, CD7 is a target marker. This assumption was based on the following reasons. (1) During several years of follow-up, transformation from low-risk MDS to high-risk MDS or AL-MDS occurs at only a low frequency, whereas transformation from high-risk MDS to AL-MDS is more common.8 (2) Among the 4 antigens, the percentage of CD7+ cases alone differed between RAEB, RAEB-t, and AL-MDS (31%, 52%, and 52%, respectively; P = .0466 for RAEB versus RAEB-t and AL-MDS). Further, the percentage of EBCs positive for CD7 (mean of data from the positive cases) was highest in AL-MDS (RAEB 38%, RAEB-t 39%, and AL-MDS 56%). We were able to examine the immunophenotype after disease progression in 8 of the 116 cases (Table 7). Compared with the immunophenotype before disease progression in each case, after disease progression the EBCs had clearly gained CD7 expression in 3 of the 8 cases (cases 6, 116, and 46) and, in addition, 2 of these 3 cases were accompanied by a decrease in CD15 expression on the EBCs (cases 116 and 46). There were 2 other cases in which CD15 expression on the EBCs decreased after disease progression (cases 49 and 45). Furthermore, the EBCs of case 46 gained CD34 expression during disease progression. Compared with these data, expression of CD10 and CD117 did not show such clear changes accompanying disease progression. These data indicate that, in the process of disease progression, the blast phenotype becomes more immature in at least some MDS cases. The decrease in CD15 expression during transformation from high-risk MDS to AL-MDS in individual cases conflicts with the data at the initial evaluation of the 116 cases, in which similar percentages of cases were CD15+ in high-risk MDS and AL-MDS. However, this conflict does not present a problem (see “Discussion”).

Prognostic value of EBC phenotype in MDS

The IPSS is a well-validated prognostic index for MDS.8 The IPSS is composed of 3 parameters—the percentage of BM blasts, degree of cytopenia, and karyotype. Although the data for these parameters change with time in MDS, the IPSS determined by the data at initial evaluation is strongly associated with the prognosis. Hence, we examined the prognostic value of the phenotype of EBCs at the initial evaluation in our MDS cases. At the time of survival analysis, 52 of the 95 MDS patients had died. The median follow-up for patients alive at the time of analysis was 20 months.

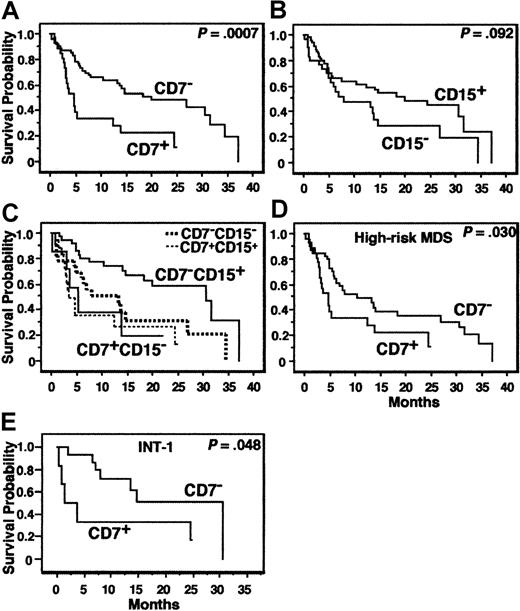

The age, IPSS, and all variables presented in Tables 3 and 4 were analyzed for the MDS patients. AL-MDS patients were excluded from the analysis. The results of prognostic analyses for the cardinal variables are summarized in Table 8. In univariate analysis, CD7 positivity (≥ 20% of EBCs expressing CD7) was significantly associated with a short OS (P = .0007, Figure 4A) and TFS (P = .014). CD15 negativity (< 20% of EBCs expressing CD15) tended to be associated with a short OS (P = .092, Figure 4B). When the MDS patients were divided into CD7+CD15−, CD7+CD15+, CD7−CD15−, and CD7−CD15+ groups, the patients with CD7−CD15+ showed the best OS curve (Figure 4C;P = .048, test for trend; P = .017, CD7−CD15+ versus CD7−CD15−; P = .0004, CD7−CD15+ versus the 3 other groups [CD7+ or CD15−]). All other variables presented in Tables 3 and 4 and the age were not associated with the prognosis, whereas the IPSS was significantly associated with the OS. Suzuki et al suggested that CD34+CD7+CD56+MPO− AL might show a poor prognosis.26 Our MDS patients with EBCs of this phenotype (n = 6) did not show any significant survival disadvantage. We then analyzed the variables associated with the prognosis by multivariate analysis. CD7 positivity was an independent variable associated with a short OS and TFS, and “CD7+and/or CD15−” was an independent variable associated with a short OS (Table 8). Because CD7+ cases did not exist in low-risk MDS, we repeated the prognostic analysis for all of the above-mentioned variables in high-risk MDS patients. In the univariate analysis, CD7 positivity was associated with a short OS (P = .030, Figure 4D) and TFS (P = .0073), but all other variables, including the IPSS, were not (P > .1).

Survival curves.

(A-C) OS of all MDS patients according to expression of CD7 or CD15 or both. AL-MDS patients were excluded from the analyses. (D) OS of the high-risk MDS patients according to CD7 expression. (E) OS of MDS patients classified as INT-1 by IPSS according to CD7 expression.

Survival curves.

(A-C) OS of all MDS patients according to expression of CD7 or CD15 or both. AL-MDS patients were excluded from the analyses. (D) OS of the high-risk MDS patients according to CD7 expression. (E) OS of MDS patients classified as INT-1 by IPSS according to CD7 expression.

We then evaluated the association between CD7 expression and IPSS. The proportion of CD7+ cases differed between IPSS categories, that is, 0 of 14 (CD7+ cases per total cases, 0%), 6 of 22 (27.3%), 7 of 17 (41.2%), and 14 of 35 cases (40.0%) in the low, INT-1, INT-2 and high categories of IPSS, respectively (Table9, P = .0347). Further, CD7 positivity was associated with a short OS and TFS in the INT-1, INT-2, and high IPSS categories with statistic significance or marginal statistical significance (Table 9 and Figure 4E).

Discussion

Density gradient centrifugation using the BR reagent is suitable for enriching blasts from patients with myeloid malignancies and lymphoid malignancies16 (and Hyodo et al, manuscript in preparation). When this method was applied to normal BM cells, both myeloblasts and immature B cells were able to be enriched. In this study, we used this reagent to enrich MDS blasts and then determined their phenotypic features. MDS is a heterogeneous group of disorders in regard to both the differentiation capacity of the clonal cells and the prognosis. However, in this paper we showed that MDS EBCs from almost all the cases had a common immunophenotype, that is, an immunophenotype of committed myeloid progenitors (CD34+CD38+HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+),27,28irrespective of the MDS subtype. Prior reports showed that an increase in CD34+ cells in the PB and the BM was associated with poor survival and a higher risk of leukemic transformation in MDS.29-31 In view of the present data that CD34 is expressed by a high percentage of EBCs in nearly all MDS cases, we consider that the prior data simply denote that an increase in blasts in the PB and the BM was associated with a poor prognosis in MDS.

Contrary to the common CD34+CD38+HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+phenotype, MDS EBCs from various proportions of cases expressed other antigens that are expressed on normal myeloid cells more mature than myeloblasts. That is, CD10 was detected in 19% of the cases, CD11b in 48%, CD15 in 64%, and CD16 in 0%. Thus, although the expression profiles of these antigens differ among MDS cases, coexpression of stem cell antigens and late-stage myeloid antigens on myeloblasts (asynchronous expression of antigens, which is well known in de novo AML [reviewed by Stelzer and Goodpasture22]) is common in MDS. In the meantime, expression of antigens restricted to lymphoid cells in normal hematopoiesis, that is, CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, CD19, and CD20, was very rare for the MDS EBCs. The exception is CD56, whose expression is observed only on NK-cell lineages and a subset of T-cell lineages in healthy subjects, which was expressed on EBCs from 27% of our cases. This is consistent with the data for de novo AML as shown in Table 5 and reported by others.32

The present data, that is, 97% of the cases expressed CD34 and 58% of the cases were MPO−, indicate that the phenotype of MDS blasts is more immature compared with de novo AML blasts, in which 35% to 60% of cases are CD34+ and 5% to 10% of cases are MPO−.20,33-36 As shown in Table 5, 47% of our de novo AML cases were CD34+. Although blasts of minimally differentiated de novo AML (AML-M0) show, by definition, a negative cytochemical reaction for MPO in all cases and are CD34+ in nearly 90% to 100% of cases,35-37MDS EBCs are CD34+ in most cases, irrespective of the MPO status. The recent WHO classification defines cases with 20% or more myeloblasts in the BM as AML.5 Because in most RAEB-t cases BM blasts exceed 20%, these cases are diagnosed as de novo AML by this classification, provided that there was no prior period of MDS. However, our finding that the EBC phenotype is similar (CD34+CD38+HLA-DR+CD13+CD33+MPO+or−) among MDS subtypes, including RAEB-t, but differs between MDS and de novo AML regarding CD34 and MPO expression indicates that RAEB-t should be retained as a separate disease entity until a more biologically suitable classification is constructed.

CD33 is a target molecule of antibody target therapy of MDS. In our cohort, EBCs from all MDS cases and 19 of the 21 AL-MDS cases were CD33+, but the percentage of EBCs positive for CD33 was variable. Recently, Estey et al reported a low response rate when MDS patients were treated with an anti-CD33 calicheamicin conjugate.38 It is important to determine whether the response to this MDS therapy is related to the degree of CD33 expression on blasts or some other factor such as expression of multidrug-resistance proteins by blasts. CD117 (RTK c-kit) is another target molecule of antibody target therapy of MDS. A recent report showed that synthetic small-molecule inhibitors of RTK inhibited phosphorylation of c-kit and a signaling event downstream of c-kit activation and induced apoptosis of CD117+ de novo AML blasts in all cases tested.14 Remission induction of an AML case by one of these inhibitors, SU5416, was also reported.39 In our cohort, EBCs from 64% of cases were CD117+, but the percentage of EBCs positive for CD117 was variable. It will be very interesting to determine whether these inhibitors are effective for the treatment of CD117+ MDS cases.

CD7 is expressed on T-lineage cells as well as a fraction of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors, which are capable of differentiating into either T cells or myeloid cells.40,41CD7+ cells expressing CD13 or CD33 (or both), which lose CD7 expression by differentiation induction, have also been reported.42 In de novo AML, CD7 expression is associated with an immature AML phenotype.20,43 Therefore, CD7 has been proposed as a marker of immaturity in myeloid cells. We have reported a strong association between the cytogenetic data and CD7 expression in 256 de novo AML cases.20 That is, when de novo AML cases were classified according to their cytogenetic data as favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable, the percentage of CD7+ patients increased stepwise from the favorable group to the intermediate and unfavorable groups (4.3%, 36.4%, and 53.2%, respectively, P < .0001). Therefore, we analyzed for cytogenetic data showing a significant association with CD7 expression in the present 116 subjects, but we could not find any significant associations (data not shown).

When the phenotype data of 116 cases were examined, expression of CD7 and CD117 (markers of immaturity of myeloid cells) was more frequent in high-risk MDS and AL-MDS compared with low-risk MDS. In particular, no low-risk MDS cases were CD7+. Conversely, expression of CD10 and CD15 (markers of maturation of myeloid cells) was more frequent in low-risk MDS compared with high-risk MDS and AL-MDS. Further, increased CD7 expression and reduced CD15 expression, which are accompanied by disease progression of MDS, were observed in sequential samples of the same subjects. These data indicate that during disease progression in MDS, phenotypical clonal evolution (transition from blasts with a relatively mature phenotype to blasts with a more immature phenotype) occurs at least in some cases. For 4 of the 5 cases who showed phenotypical clonal evolution in Table 7, cytogenetic data were available from both before and after disease progression (cases 45, 46, 49, and 116). Clonal evolution revealed by the karyotype was not detected in 2 of the 4 cases (cases 45 and 49) and was observed only after full transformation to leukemia in case 46. Both clonal evolution (intrinsic changes in clonal cells) and blunted host defense may cause disease progression in MDS. Hopefully, the EBC immunophenotype will supplement the karyotype data in the detection of clonal evolution in MDS. There is a possibility that blasts from a normal clone may be present in EBCs in MDS samples, especially in low-risk MDS. Nevertheless, this possibility cannot readily explain the differences in immunophenotype between low-risk MDS, high-risk MDS, and AL-MDS. This is because we showed in a separate project that the immunophenotype of myeloblasts, prepared by BR density centrifugation from hematologically healthy individuals, is CD13+CD33+CD34+CD117+or−CD7−CD10−CD15−(n = 10, detailed data not shown). As described in “Results,” the decrease in CD15 expression during transformation from high-risk MDS to AL-MDS in individual cases conflicts with the data at the initial evaluation of the 116 cases. This conflict may be explained by the following 2 findings. (1) Some MDS cases developed as low-risk MDS and slowly progressed to high-risk MDS, whereas other cases developed as high-risk with no or only a short undiagnosed period of low-risk MDS. Among this heterogeneous population of high-risk MDS patients, a fraction of patients shows disease progression within the limited follow-up period. Therefore, the phenotypic data of patients who showed transition from high-risk MDS to AL-MDS during our follow-up period may be data from a select population. (2) The immunophenotypic changes in MDS are not uniform phenomena. There are probably many cases whose blast immunophenotype does not change after disease progression.

We showed that CD7 positivity, with or without consideration of the CD15 expression status, was an independent variable associated with a poor prognosis for MDS. Although the in vivo function of CD7 is largely unknown, it may be involved in T- and NK-cell activation and adhesion as well as production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by myeloid precursors.44-47 It remains unknown whether these putative functions of CD7, blast immaturity itself, or other factors explain the poor prognosis of CD7+ MDS cases. Regarding de novo AML, there is continued debate over whether CD7 expression is associated with a poor prognosis (for a review, see Ogata et al20). However, in our recent study examining 256 de novo AML cases, we showed a strong association between the cytogenetic data and CD7 expression as described above, which explains why the prognostic value of CD7 expression has been contradictory in de novo AML.20 Further, CD7 expression was associated with an extremely poor prognosis only when de novo AML patients with unfavorable cytogenetics were analyzed.20 The finding that CD7 expression was associated with a poor prognosis in disease groups that per se have a poor prognosis, that is, MDS and de novo AML with unfavorable cytogenetics, is interesting. The biologic background that explains this finding needs to be studied further.

In conclusion, this is the first report to clarify the detailed phenotypic features of MDS blasts and their clinical significance. We believe that the data presented here are clinically useful and important for understanding the pathophysiology of MDS.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 18, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0222.

Supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (no. 14571002).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Kiyoyuki Ogata, Division of Hematology, Third Department of Internal Medicine, Nippon Medical School, Sendagi 1-1-5, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8603, Japan; e-mail:ogata@nms.ac.jp.