Endoglin is an endothelial membrane glycoprotein involved in cardiovascular morphogenesis and vascular remodeling. It associates with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling receptors to bind TGF-β family members, forming a functional receptor complex. Arterial injury leads to up-regulation of endoglin, but the underlying regulatory events are unknown. The transcription factor KLF6, an immediate-early response gene induced in endothelial cells during vascular injury, transactivates TGF-β, TGF-β signaling receptors, and TGF-β–stimulated genes. KLF6 and, subsequently, endoglin were colocalized to vascular endothelium (ie, expressed in the same cell type) following carotid balloon injury in rats. After endothelial denudation, KLF6 was induced and translocated to the nucleus; this was followed 6 hours later by increased endoglin expression. Transient overexpression of KLF6, but not Egr-1, stimulated endogenous endoglin mRNA and transactivated the endoglinpromoter. This transactivation was dependent on a GC-rich tract required for basal activity of the endoglin promoter driven by the related GC box binding protein, Sp1. In cells lacking Sp1 and KLF6, transfected KLF6 and Sp1 cooperatively transactivated theendoglin promoter and those of collagen α1(I), urokinase-type plasminogen activator, TGF-β1, and TGF-β receptor type 1. Direct physical interaction between Sp1 and KLF6 was documented by coimmunoprecipitation, pull-down experiments, and the GAL4 one-hybrid system, mapping the KLF6 interaction to the C-terminal domain of Sp1. These data provide evidence that injury-induced KLF6 and preexisting Sp1 may cooperate in regulating the expression of endoglin and related members of the TGF-β signaling complex in vascular repair.

Introduction

Coordinated gene expression is a crucial requirement in the response to tissue injury. Extracellular matrix proteins,1-3 growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β),1,4,5 and proteases such as urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)6,7 are jointly regulated. In particular, the TGF-β family plays a central role in the injury response based on the following: (1) TGF-β1 expression is up-regulated after injury;8,9 (2) infusion of TGF-β polypeptide or transfection of cDNA into injured arteries increases extracellular matrix production;1,10 and (3) antibodies to TGF-β reduce intimal hyperplasia.11

Members of the TGF-β superfamily exert their biologic functions through membrane receptors known as type 1 (TβRI) and type 2 (TβRII) serine/threonine kinases. After ligand binding, TβRII recruits and phosphorylates TβRI, which initiates the signaling pathway by phosphorylating the Smad family of proteins.12,13 Endoglin is a homodimeric membrane glycoprotein that functions, in association with TβRI and TβRII, as an auxiliary receptor for TGF-β1, TGF-β3, activin, bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), and BMP-7.14-16It is highly expressed by endothelial cells17,18 and, at lower levels, by activated monocytes/macrophages19 and by mesenchymal cells, including fibroblasts,20 and vascular smooth muscle cells.21 22

Accumulating evidence suggests an important role for endoglin in vascular remodeling and cardiovascular development. Endoglin expression is regulated during heart development in humans and chicken;23-25 it is highly expressed at the level of the endocardial cushion during valve formation and by the mesenchymal cells of the atrioventricular canal during heart septation.23Its role in morphogenesis is further underscored by the finding that mice embryos homozygous for a mutant endoglin die at 10 to 10.5 days after coitum because of vascular and cardiac anomalies.25-27

The gene encoding endoglin is also the target for the autosomal dominant disorder known as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 (HHT1) (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome).28 The most common clinical manifestations of HHT1 are the development of vascular telangiectases in skin and nasal mucosa with bleeding and arteriovenous malformations in lung, liver, and brain.29,30 Interestingly, fibrosis and cirrhosis also develop in some patients with liver involvement, suggesting that the hepatic injury response is also defective.31

Reduced levels of functional endoglin (haploinsufficiency), rather than a dominant-negative effect of the mutant allele, is widely accepted as the pathogenic mechanism of HHT1.30,32 For this reason, studies elucidating the regulation of endoglin gene expression are essential to ultimately correct HHT1. In this regard, we have characterized the promoter region of the human endoglingene,33 and, more recently, we found that the proximal upstream promoter contains a critical Sp1 site required for its basal activity and that Sp1 is involved in the TGF-β–mediated induction of the endoglin promoter by way of its interaction with Smad3/Smad4.34

Endoglin expression is up-regulated in microvascular endothelial cells in human and porcine models of tissue repair.35,61However, the molecular basis for endoglin gene stimulation in this pathologic setting is unknown. Krüppel-like factor 6 (KLF6), previously called Zf9/COPEB, is a zinc finger transcription factor cloned from hepatic mesenchymal cells, placenta, and leukocytes.36,37 It belongs to the family of Krüppel-like transcription factors, which recognize a GC box motif in responsive promoters.36,38 A role for KLF6 in response to tissue injury is suggested by its rapid induction in activated hepatic stellate cells, the key fibrogenic cell type in liver injury, and by its induction in endothelial cells after vascular injury.39 Moreover, KLF6 transactivates key genes directly involved in the injury response, including collagen α(I), TGF-β1, TβRI, TβRII, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) genes.37,39 40

Based on the induction of endoglin35 andKLF639 during vascular injury and the dependence of endoglin transactivation on GC boxes, we have explored the capacity of KLF6 to regulate endoglin gene expression. We have colocalized KLF6 and subsequent endoglininduction in vascular endothelial cells following carotid balloon injury in rats. Moreover, endothelial injury in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) led to the immediate induction of KLF6, followed 6 hours later by the up-regulation ofendoglin. Furthermore, KLF6 stimulates endoglinpromoter activity, which is dependent on a region overlapping an Sp1 site. Finally, functional and physical cooperation between KLF6 and Sp1 leads to marked up-regulation not only of endoglin, but also of TGF-β1 and other key members of the TGF-β signaling complex.

Materials and methods

KLF6 and endoglin detection in arterial injury

The distal half of the left common carotid artery of a Sprague-Dawley rat was denuded of endothelium by 3 passages of a 2F catheter balloon as described.39 Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with antibodies against KLF6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or endoglin (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Color development was performed, with diaminobenzidine and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Cells

HUVECs were grown in medium 199 containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 50 μg/mL bovine brain extract on 0.5% gelatin-coated dishes. Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs), M1 human fibroblasts, COS-7 monkey kidney cells, and HeLa human carcinoma cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% FCS. The U-937 human monocytic cell line was grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS. The human endothelial cell line HMEC-1 was grown with 0.1% gelatin coating in MCDB-131 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 2 μg/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF), and 100 μg hydrocortisone. Drosophila Schneider SL-2 cells were grown in Shield and Sang Drosophila-enriched Schneider (DES) insect medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% FCS.

For endothelial denudation injury, 50- to 300-μm–wide wounds were systematically created with a sterile pipette tip throughout a confluent monolayer of HUVECs until only 20% of the cells remained adherent to the culture dish. Plates were washed, fresh medium was added, and cells were cultured at 37°C.

Flow cytometry

In endothelial denudation experiments, endoglin expression was determined in HUVECs by incubation with the mouse monoclonal antibody P4A4 against human endoglin.41 For KLF6 analysis, HUVECs were fixed in 3.5% formaldehyde and were permeabilized with 100 μg/mL lysophosphatidyl choline before incubation with the primary antibody (Zf9; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–Labeled rabbit anti–mouse IgG (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and washed, and their fluorescence was estimated with an EPICS-XL (Coulter, Hialeah, FL) using logarithmic amplifiers.

To investigate the effect of KLF6 on endogenous endoglin expression, HeLa cells were cotransfected with KLF6(pCIneo-KLF6)39 and the green fluorescence protein (pEGFP-C2; BD Biosciences) expression vectors (1 μg/well each) using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Barcelona, Spain). After 24 hours, cells were incubated with P4A4 antibody, followed by FluoroLinkCy5-labeled goat anti–mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences, Barcelona, Spain). Fluorescence was estimated with a FACSVantage (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from HUVECs and from HeLa and M1 cells using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and was reverse transcribed by avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcription (RT). The resultant cDNA was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed with a combination of specific oligonucleotide primers for KLF6 (5′-CGGCCAAGTTTACCTCCG-3′ and 5′-CATGAGCATCTGTAAGGC-3′), endoglin (5′-TCCATTGTGACCTTCAGCC-3′ and 5′-GGAGATGCAGGAAGACACTG-3′ for HeLa and M1 cells or 5′-TGGTACATCTACTCGCACACGC-3′ and 5′-GGCTATGCCATGCTG CTGGTGG-3′ for HUVECs and BAECs), actin (5′-AGGCCAACCGCGAAGATTGACC-3′ and 5′-GAAGTCCAGGGCGACGTAGCAC-3′) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (5′-GGCTGAGAACGGGAAGCT TGTCA-3′ and 5′-CGGCCATCACGCCACACAGT-3′) and AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). Amplified products were analyzed in agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and quantified by densitometry.

Endoglin mRNA analysis by real-time PCR

BAECs were grown to 70% confluence and were transiently transfected with pCIneo or pCIneo-KLF6 plasmids using lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Cells were harvested, and total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNAqueous-4PCR Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Synthesis of cDNA was performed on 2 μg total RNA per sample with random primers using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI). For quantitative analysis of endoglin mRNA, the reverse transcriptase product was diluted 4 times in nuclease-free H2O and was loaded as a PCR volume of 10 μL for real-time PCR in an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Amplifications were performed using oligonucleotide primers for bovine GAPDH (AJ000039) as a housekeeping gene (5′-CAATGACCCCTTCATTGACC-3′ and 5′-GATCTCGCTCCTGGAAGATG-3′) and for the conserved endoglin cytoplasmic domain (see above) and SYBR Green.

Endoglin promoter plasmid construction

The different constructs of the endoglin promoter were generated by PCR amplification of the 3.3-kb SacII/SacII fragment of the endoglin promoter.33 Oligonucleotides corresponding to positions −2450/−2436, −1950/−1936, −965/−951, −450/−436, −350/−336, −250/−236, −150/−136, −50/−36, and +50/+64 were used in combination with the common oligonucleotide +336/+350. Each of these oligonucleotides contained theHindIII site in 5′ and the XhoI site in 3′. After PCR amplification, the resultant products were purified, double digested with HindIII and XhoI, and cloned at theHindIII/XhoI sites of the pXP2vector42 to generate the following constructs:pCD105(−2450/+350), pCD105(−1950/+350),pCD105(−965/+350), pCD105(−450/+350),pCD105(−350/+350), pCD105(−250/+350),pCD105(−150/+350), pCD105(−50/+350), andpCD105(+50/+350). The Sp1 site mutant of pCD105 (−50/+350) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis.34

GAL-4 one-hybrid system constructs

The KLF6-GAL4 and GAL4-Sp1 constructs and GAL4-LUC reporter were used as described.37Drosophila expression vector encoding the 778 amino acids of full-length Sp1 (pAC-Sp1) was a generous gift from Dr Robert Tjian.43 PlasmidspAc-ΔNSp1 (deletion of amino acids 2-257), −ΔMSp1(deletion of amino acids 265-548), and −ΔCSp1(deletion of amino acids 552-778) were constructed by ligating end-filled AccI-XbaI fragments from the corresponding pCIneo Sp1 deletion mutants into dephosphorylated end-filled XhoI pAC. OriginalpCIneo-ΔN, −ΔM, and −ΔCdeletion mutants were constructed with PCR amplification using the Sp1 cloning vector as a template and was subcloned into theXbaI/AccI site of the pCIneo mammalian expression vector (Promega, WI). The following primers were used: 5′-ACCTTGCTACCTGTCAACAGC-3′ and 5′-CATGGGGGGATCCACTAGTT-3′ for ΔN cDNA; 5′-AATGCCCCAGGTGATCATGG-3′ and 5′-GCTGTTGACAGGTAGCAAGG-3′ for ΔM cDNA; 5′-GCTTCTGAGATCAGGCAC-3′ and 5′-CACCTGGGGCATTTGCTATAGC-3′ for ΔC cDNA.

Transient transfection

Mammalian expression vectors encoding KLF6(pCIneo-KLF6) and Sp1 (pCIneo-Sp1),Drosophila expression vectors encoding KLF6(pAC-KLF6) and Sp1 (pAC-Sp1), and bacterial expression vector encoding GST-KLF6 fusion protein(pGEX-KLF6) have been described.39 40pcDNA3-EGR1 expression vector encoding EGR1 was kindly provided by Dr Ward (Bath University, United Kingdom). Transient transfection was performed using SuperFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) in serum-free medium containing 1 μg endoglin promoter constructs, with or without KLF6-pCIneo,KLF6-pAC, or the same expression vector for Sp1. All transfections contained the same amount of total DNA (2 μg), with the balance composed of the corresponding empty expression vectors. Luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates using a TD20/20 luminometer (Promega). Correction for transfection efficiency was made by cotransfection with pCMV–β-galactosidase (BD Biosciences), using galactolight (Tropix) as a substrate. Transactivation assay results were expressed as arbitrary units of luciferase activity or as a -fold induction with respect to the corresponding untreated sample.

For experiments documenting functional cooperation, transient transfection was performed in Drosophila cells using Cellfectin reagents (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) in 1 mL serum-free medium containing a combination of different amounts ofSp1-pAC and KLF6-pAC, with or without 500 ng reporter plasmids. These reporters were composed of luciferase cDNA fused with either the collagen α1(I) promoter(pGL-Col3),44 the full length human TGF-β1 promoter (phTG5luc),40 the TβRI promoter (−867 to −228) (pTβRIP-Luc),40 the uPA promoter (pUK-Luc),45 or 3 tandem repeats of the consensus GC boxes plus TATA box(GC3-Luc).45pAC was used as empty vector to adjust the total amount of DNA to 2 μg per sample. After a 4-hour incubation, 1 mL medium containing 20% FCS was added to the cultures and was further incubated for 48 hours. Thereafter, luciferase assays were performed as described.45

Immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down

Forty hours after transfection, COS-7 cells were lysed,34 and total extracts were incubated with anti-Sp1 or anti-Zf9/KLF6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunocomplexes were precipitated with protein-G Sepharose and were separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to Hybond-C extra nitrocellulose (Amersham Biosciences) and probed with antibodies, and signals were developed using the Super Signal reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for enhanced chemiluminescence. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times with similar results, and a representative experiment is shown in the corresponding figure. The glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein GST-KLF6 has been described.39

Direct binding of KLF6 and Sp1 was performed using recombinant Sp1 (Promega) and KLF6-GST.45 Samples were combined with either glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads or anti-Sp1 antibody-conjugated agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and were incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotating mixer. Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed using rabbit polyclonal anti-Sp1 or anti-Zf9/KLF6 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) as before.45 Protein bands were visualized using the Amersham Biosciences enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system.

Results

KLF6 and endoglin expression are increased in carotid artery after balloon injury

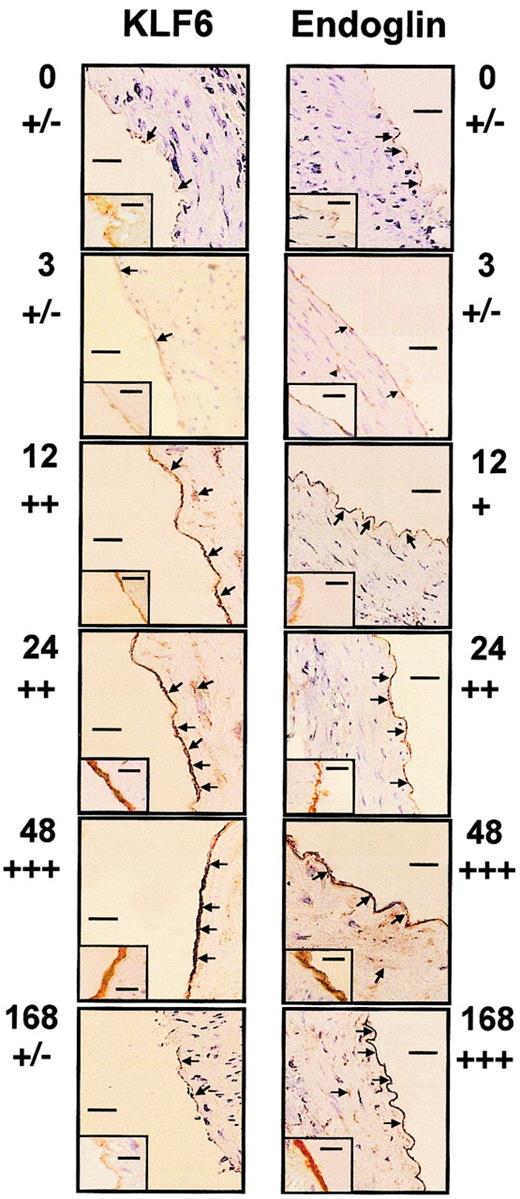

We examined whether KLF6 colocalized with endoglin to vascular endothelial cells when arterial injury occurred based on KLF6 colocalization with uPA in these cells.39 In healthy coronary arteries, endoglin is present at low abundance and is found primarily on endothelial cells, adventitial fibroblasts, and some medial smooth muscle cells.35 To analyze the potential role of KLF6 as an activator of endoglin transcription after vascular injury in vivo, the distal half of the left carotid artery of rats was injured with a balloon catheter and was immunostained with endoglin and KLF6 antibodies at progressive intervals (Figure1). In resting endothelium and at 3 hours after injury, endoglin and KLF6 were expressed weakly, whereas 12 hours after injury, KLF6 was clearly induced. This induction was maintained up to 48 hours and decayed afterward; at 7 days, KLF6 levels were similar to those of resting endothelium. On the other hand, the kinetics of endoglin staining revealed a time delay with respect to KLF6. Endoglin up-regulation started at 24 hours, peaked at 48 hours, and was sustained for at least 7 days after injury, consistent with the high stability of the protein.46 At 24 to 48 hours, endoglin and KLF6 levels were greatly increased in vascular endothelial cells. Weak immunoreactivity was also detected in the medial smooth muscle cells of the injured carotid artery, similar to what we previously observed for uPA.39 When the same incubations were made with an irrelevant nonimmune antibody, no signal was detected, confirming the specificity of expression. These results demonstrate that KLF6 induction precedes endoglin up-regulation in vascular endothelial cells.

Colocalization of KLF6 and endoglin in arterial endothelial cells after carotid balloon injury in rats.

The distal half-carotid artery of rats was injured with a balloon catheter. At 0, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 168 hours after injury (as indicated beside each photo), the carotid was perfusion fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, excised, and paraffin embedded. Sections were stained with antiendoglin (right panels) or anti-KLF6 (left panels), as described in “Materials and methods.” Panels show the staining pattern of the adjacent proximal half of the carotid artery. Arrows indicate staining of the endothelial layer and some scattered cells present in the tunica media. An inset in each panel represents the immunostaining at higher original magnification (× 1000), whereas the main figures are shown at × 200 original magnification. Bars represent 50 μm (main figures) or 1 μm (insets). Estimations of relative levels of KLF6 and endoglin at different time points are indicated below time markers.

Colocalization of KLF6 and endoglin in arterial endothelial cells after carotid balloon injury in rats.

The distal half-carotid artery of rats was injured with a balloon catheter. At 0, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 168 hours after injury (as indicated beside each photo), the carotid was perfusion fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, excised, and paraffin embedded. Sections were stained with antiendoglin (right panels) or anti-KLF6 (left panels), as described in “Materials and methods.” Panels show the staining pattern of the adjacent proximal half of the carotid artery. Arrows indicate staining of the endothelial layer and some scattered cells present in the tunica media. An inset in each panel represents the immunostaining at higher original magnification (× 1000), whereas the main figures are shown at × 200 original magnification. Bars represent 50 μm (main figures) or 1 μm (insets). Estimations of relative levels of KLF6 and endoglin at different time points are indicated below time markers.

Endothelial denudation of HUVECs sequentially induces KLF6 and endoglin

To explore the temporal relationship between KFL6 and endoglin expression in an injury model in which expression could be quantified and clearly ascribed to endothelial cells, denudation injury was performed in HUVECs, and cells were analyzed at different intervals by RT-PCR, flow cytometry, and fluorescence microscopy.

The expression of KLF6 and endoglin mRNA was analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR using total RNA from denuded HUVEC monolayers. As a control, levels of the transcription factor Sp1, involved in basal transcription of endoglin,34 were also monitored. After 20 cycles of PCR, specific cDNA bands of 318, 179, and 300 bp—corresponding to KLF6, endoglin,47 and Sp1, respectively—were detected. KLF6 and endoglin bands were quantified by densitometry and were expressed relative to an actin cDNA control product (Figure 2A). KLF6 RNA was rapidly and transiently induced (approximately 2.5-fold) within the first hour of wounding. This is similar to the time course and magnitude of KLF6 induction following activation of hepatic stellate cells in liver injury.37 By contrast, Sp1 levels remained high and unchanged during the whole process. After the transient induction of KLF6, endoglin mRNA expression rose approximately 2.5-fold at 6 to 12 hours and decreased thereafter. This temporal pattern is consistent with the possibility that KLF6 induction leads to the subsequent up-regulation of endoglin.

KLF6 and endoglin expression and localization after endothelial denudation in HUVECs.

(A) RT-PCR after HUVEC endothelial denudation. HUVECs were grown and wounded as described in “Materials and methods.” At different times (1-24 hours) after wounding, cells were lysed and RNA was extracted and processed for RT-PCR with KLF6 (K), endoglin (E), Sp1 (S), and actin (A) primers. After 20 cycles, PCR reactions were separated on a 3% Nu-Sieve agarose gel, and bands were quantified by densitometry, then plotted relative to actin cDNA as shown in the bar graph on the right. Shown is 1 of 4 representative experiments that gave similar results. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of endoglin and KLF6. HUVECs were wounded extensively, leaving approximately 20% of the total monolayer remaining intact. After different intervals (0-36 hours), cells were processed for flow cytometry. To detect endoglin on the cell surface, incubation with monoclonal antibody P4A4 was used as described in “Materials and methods.” To detect total KLF6, cells were permeabilized before antibody incubation as described in “Materials and methods.” Cytometry profiles for endoglin and KLF6 are shown on the left and, for comparative purposes, contain a vertical dotted line that indicates the fluorescence intensity of unwounded HUVECs. On the right, a plot summarizing the protein levels during the denudation process is included. Shown is 1 of 5 representative experiments that gave similar results. (C) Immunostaining for KLF6 and endoglin in HUVECs after endothelial denudation. HUVECs, grown as monolayers on gelatinized coverslips, were wounded with a tip of pipette in the middle of the monolayer. For KLF6 immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-KLF6 antibody, then washed and incubated with an FITC goat-antirabbit antibody (green fluorescence). For endoglin staining, cells were incubated with P4A4 mouse antibody, followed by a secondary anti–mouse IgG coupled to Alexa 546 (red fluorescence). Representative micrographs from 50 different fields with similar results are presented. Single (top and middle rows) and double (bottom row) immunostaining shows that KLF6 translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, whereas endoglin always localizes to the plasma membrane. Original magnification top panels, × 100; middle and bottom panels, × 60.

KLF6 and endoglin expression and localization after endothelial denudation in HUVECs.

(A) RT-PCR after HUVEC endothelial denudation. HUVECs were grown and wounded as described in “Materials and methods.” At different times (1-24 hours) after wounding, cells were lysed and RNA was extracted and processed for RT-PCR with KLF6 (K), endoglin (E), Sp1 (S), and actin (A) primers. After 20 cycles, PCR reactions were separated on a 3% Nu-Sieve agarose gel, and bands were quantified by densitometry, then plotted relative to actin cDNA as shown in the bar graph on the right. Shown is 1 of 4 representative experiments that gave similar results. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of endoglin and KLF6. HUVECs were wounded extensively, leaving approximately 20% of the total monolayer remaining intact. After different intervals (0-36 hours), cells were processed for flow cytometry. To detect endoglin on the cell surface, incubation with monoclonal antibody P4A4 was used as described in “Materials and methods.” To detect total KLF6, cells were permeabilized before antibody incubation as described in “Materials and methods.” Cytometry profiles for endoglin and KLF6 are shown on the left and, for comparative purposes, contain a vertical dotted line that indicates the fluorescence intensity of unwounded HUVECs. On the right, a plot summarizing the protein levels during the denudation process is included. Shown is 1 of 5 representative experiments that gave similar results. (C) Immunostaining for KLF6 and endoglin in HUVECs after endothelial denudation. HUVECs, grown as monolayers on gelatinized coverslips, were wounded with a tip of pipette in the middle of the monolayer. For KLF6 immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-KLF6 antibody, then washed and incubated with an FITC goat-antirabbit antibody (green fluorescence). For endoglin staining, cells were incubated with P4A4 mouse antibody, followed by a secondary anti–mouse IgG coupled to Alexa 546 (red fluorescence). Representative micrographs from 50 different fields with similar results are presented. Single (top and middle rows) and double (bottom row) immunostaining shows that KLF6 translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, whereas endoglin always localizes to the plasma membrane. Original magnification top panels, × 100; middle and bottom panels, × 60.

Protein expression after endothelial denudation was also measured at different times using flow cytometry. The cytometry profiles for endoglin and KLF6 are shown side by side, together with a graphic summarizing the protein dynamics during the denudation process (Figure 2B). Expression of endoglin clearly increased over the levels of unwounded HUVECs approximately 12 hours after injury, and this increase was maintained afterward (36 hours). KLF6 expression increased after 2 hours and peaked at 6 hours, whereas endoglin expression followed 6 hours after the early induction of KLF6. This figure is consistent with pulse-chase analysis of endoglin in HUVECs.46

The subcellular localization of KLF6 and endoglin after injury in HUVECs was studied by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 2C). At time 0, KLF6 was evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, whereas nuclei lacked expression. After 3 hours, the cells at the wound edge displayed increased expression of KLF6, including some nuclei expression. Nuclear localization of KLF6 peaked at 6 hours and then KLF6 returned to the cytoplasm, mimicking the behavior of KLF6 after injury in activated hepatic stellate cells.37 After 24 hours, HUVEC growth restored the integrity of the monolayer and the expression of KLF6 to that observed before the onset of injury. On the other hand, endoglin staining was only found at the plasma membrane at all time points. Given the basal high levels of endoglin expression in HUVECs48 and the limitations of this technique, no quantitative differences could be inferred. Although endoglin appeared to be evenly distributed on the cell surface, KLF6 translocated from an early, dispersed cytoplasmic distribution to a conspicuous localization in the nucleus at 3 to 6 hours after injury. After 8 hours, the process of nuclear localization was reversed, and KLF6 was only found in the cytoplasm. There was no specific staining when cells were incubated with the secondary antibody alone (data not shown).

Increased endogenous endoglin mRNA expression following transient transfection of KLF6

To establish endoglin as a potential transcriptional target of KLF6, transient transfection was performed in HeLa cells, M1 fibroblasts, and BAECs, which express different levels of endogenous endoglin. Endoglin was detected by flow cytometry in nontransfected versus KLF6-transfected HeLa cells (Figure3A). Endoglin transcripts were also quantitated by RT-PCR in HeLa and M1 cells after transient transfection of KLF6 (Figure 3B-C). Mean fluorescent intensity from endogenous endoglin was increased on KLF6 transfection (Figure 3A), whereas mock transfection with empty vector, pCIneo, did not alter endoglin levels significantly (data not shown). Moreover, the levels of endoglin RNA were much higher after KLF6 transfection in HeLa cells (Figure 3B) and in M1 fibroblasts (Figure 3C). After 20 cycles of PCR, only the endoglin-specific band was visible in KLF6-transfected HeLa and M1 cells. This and the calculated ratio of endoglin versus GAPDH RNA levels confirmed the specificity of the endoglin promoter's response to KLF6 (Figure 3B-C). As a control for KLF6 specificity, cells were separately transfected with Egr-1, a member of the same Krüppel-like transcription factor family as KLF6;Egr-1 did not alter endogenous levels of endoglin (Figure3A). The induction of endogenous endoglin mRNA by KLF6 was also confirmed using quantitative real-time RT-PCR in BAECs. Endoglin transcription levels were increased 3.2- or 4-fold after transfection with 5 or 10 μg KLF6 plasmid, respectively, compared to transfection with the empty vector (Figure 3D). This transcriptional activity is remarkably similar to the effect of KLF6 on other gene targets.37

Endoglin induction by KLF6 after transient transfection.

(A) Analysis of endogenous endoglin expression in HeLa cells by flow cytometry. HeLa cells were cotransfected with 4 μg pCIneo KLF6 (KLF6), pCIneo, pcDNA3-EGR1 (EGR1), orpcDNA3, and 1 μg pEGFP-C2 (GFP), as indicated. Transfected and untransfected cells were stained with the mouse monoclonal antibody P4A4 (antiendoglin), followed by incubation with FluoroLink Cy5-labeled goat-anti–mouse IgG. Cells were washed with PBS, and their fluorescence was estimated with a FACSVantage by detecting the Cy5 (absorbance at 649 nm, emission at 670 nm) and the green fluorescence protein (absorbance at 488 nm, emission at 507 nm) fluorochromes. Transfected cells were previously sorted using the green fluorescence protein as a transfection marker. Surface expression of endoglin was measured by detecting the fluorescence of Cy5. Numbers in the upper right corner indicate the mean fluorescence intensity from endoglin. In parentheses are shown the fold induction values for KLF6 (1.5) and EGR1 (1.1) with respect to the corresponding empty vectors. Staining with an irrelevant antibody (control antibody) was also included as a negative control. The broken vertical line indicates the fluorescence intensity of the negative control. Shown is 1 of 5 representative experiments that gave similar results. (B-C) RT-PCR analysis of endoglin and GAPDH mRNA levels in mock versus KLF6-transfected HeLa (B) and M1 (C) cells. Cells were transfected with 4 μg empty vector (M) or pCIneo-KLF6 (K). Aliquots from the PCR reaction were isolated after the indicated number of cycles and were analyzed by electrophoresis in 5% Nu-Sieve agarose gels. Bar graphs representing densitometry quantification of endoglin/GAPDH ratios from cells transfected with empty vector (■) orpCIneo-KLF6 (▪) are shown on the right. (D) Induction of endogenous endoglin expression after transfection with KLF6. BAECs were grown on 10-cm plastic plates and transiently transfected withpCIneo empty vector (control) or pCIneo-KLF6plasmid (5 or 10 μg). Cells were harvested 24 hours later, total RNA was extracted, and synthesis of cDNA was performed. Comparative quantitation of endoglin mRNA to GAPDH was analyzed with real-time RT-PCR. Fluorescence signals were analyzed during each of 40 cycles (denaturation 15 seconds at 95°C, annealing 15 seconds at 56°C, and extension 40 seconds at 72°C). Relative expression was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method. CT indicates the fractional cycle number at which the amplified gene amounts to a fixed threshold within the linear phase of amplification. Median CT of triplicate measurements was used to calculate ΔCT as the difference in CTfor endoglin and GAPDH. ΔCT for each sample was compared to the control CT and expressed as ΔΔCT. Data are expressed as fold induction of endoglin (normalized for GAPDH), compared with vector-transfected cells, with the formula 2−Δ (CT). Shown is 1 of 2 representative experiments.

Endoglin induction by KLF6 after transient transfection.

(A) Analysis of endogenous endoglin expression in HeLa cells by flow cytometry. HeLa cells were cotransfected with 4 μg pCIneo KLF6 (KLF6), pCIneo, pcDNA3-EGR1 (EGR1), orpcDNA3, and 1 μg pEGFP-C2 (GFP), as indicated. Transfected and untransfected cells were stained with the mouse monoclonal antibody P4A4 (antiendoglin), followed by incubation with FluoroLink Cy5-labeled goat-anti–mouse IgG. Cells were washed with PBS, and their fluorescence was estimated with a FACSVantage by detecting the Cy5 (absorbance at 649 nm, emission at 670 nm) and the green fluorescence protein (absorbance at 488 nm, emission at 507 nm) fluorochromes. Transfected cells were previously sorted using the green fluorescence protein as a transfection marker. Surface expression of endoglin was measured by detecting the fluorescence of Cy5. Numbers in the upper right corner indicate the mean fluorescence intensity from endoglin. In parentheses are shown the fold induction values for KLF6 (1.5) and EGR1 (1.1) with respect to the corresponding empty vectors. Staining with an irrelevant antibody (control antibody) was also included as a negative control. The broken vertical line indicates the fluorescence intensity of the negative control. Shown is 1 of 5 representative experiments that gave similar results. (B-C) RT-PCR analysis of endoglin and GAPDH mRNA levels in mock versus KLF6-transfected HeLa (B) and M1 (C) cells. Cells were transfected with 4 μg empty vector (M) or pCIneo-KLF6 (K). Aliquots from the PCR reaction were isolated after the indicated number of cycles and were analyzed by electrophoresis in 5% Nu-Sieve agarose gels. Bar graphs representing densitometry quantification of endoglin/GAPDH ratios from cells transfected with empty vector (■) orpCIneo-KLF6 (▪) are shown on the right. (D) Induction of endogenous endoglin expression after transfection with KLF6. BAECs were grown on 10-cm plastic plates and transiently transfected withpCIneo empty vector (control) or pCIneo-KLF6plasmid (5 or 10 μg). Cells were harvested 24 hours later, total RNA was extracted, and synthesis of cDNA was performed. Comparative quantitation of endoglin mRNA to GAPDH was analyzed with real-time RT-PCR. Fluorescence signals were analyzed during each of 40 cycles (denaturation 15 seconds at 95°C, annealing 15 seconds at 56°C, and extension 40 seconds at 72°C). Relative expression was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method. CT indicates the fractional cycle number at which the amplified gene amounts to a fixed threshold within the linear phase of amplification. Median CT of triplicate measurements was used to calculate ΔCT as the difference in CTfor endoglin and GAPDH. ΔCT for each sample was compared to the control CT and expressed as ΔΔCT. Data are expressed as fold induction of endoglin (normalized for GAPDH), compared with vector-transfected cells, with the formula 2−Δ (CT). Shown is 1 of 2 representative experiments.

Transcriptional activation of the endoglinpromoter by KLF6

To further establish endoglin as a transcriptional target of KLF6, transient cotransfection was performed in HeLa cells, which express low levels of endoglin and display a relatively high efficiency of transfection, using serial deletions of the endoglin promoter driving expression of the luciferase gene (Figure4A). The basal activity of the full-length promoter construct (−2450/+350) was similar to that of smaller constructs, including −350/+350, −250/+350, and −150/+350. Interestingly, a significant decrease in the basal promoter activity was observed in the intermediate constructs −1950/+350, −965/+350, and −450/+350, suggesting the presence of a repressor sequence within the −1950/−450 fragment. This finding is in agreement with the activity found in a different series of endoglin promoter constructs.49 When KLF6 was cotransfected with the panel of promoter plasmids, the activity was stimulated in all constructs (from 1.8- to 3.2-fold induction), except in the most minimal construct, pCD105(+50/+350). As shown in Figure 4B, the KLF6 transactivation effect was also observed in M1 human fibroblasts (from 2.5- to 4.3-fold induction) and in the human endothelial cell line HMEC-1 (from 1.7- to 3.5-fold induction), usingpCD105(−2450/+350), pCD105(−1950/+350),pCD105(−450/+350), and pCD105(−50/+350) as representative promoter constructs. For these cell types, the minimal construct pCD105(+50/+350) was again not transactivated.

Transactivation of the endoglin promoter by KLF6.

(A) Diagram depicting the endoglin promoter-reporter constructs is shown on the left. These reporter constructs were cotransfected with the KLF6 expression vector (▪) or the corresponding empty vector (■) in HeLa cells. Transcriptional activity was measured 24 hours later by the luciferase reporter assay and plotted as relative luciferase units (RLU). Shown is 1 of 4 representative experiments. Standard deviations are indicated. Numbers to the right of the closed bars indicate the -fold induction values after KLF6 transfection. (B) HMEC-1, M1, and Schneider 2 (SL-2) cells were transiently cotransfected with the indicated endoglin reporter constructs and the KLF6 expression plasmid, and the transcriptional activity was measured 24 hours later by the luciferase reporter assay. KLF6-transfected–sample-fold induction is expressed relative to cells transfected with an empty vector, whose arbitrary value is 1. The means of 3 different experiments (± SD) are shown in each panel.

Transactivation of the endoglin promoter by KLF6.

(A) Diagram depicting the endoglin promoter-reporter constructs is shown on the left. These reporter constructs were cotransfected with the KLF6 expression vector (▪) or the corresponding empty vector (■) in HeLa cells. Transcriptional activity was measured 24 hours later by the luciferase reporter assay and plotted as relative luciferase units (RLU). Shown is 1 of 4 representative experiments. Standard deviations are indicated. Numbers to the right of the closed bars indicate the -fold induction values after KLF6 transfection. (B) HMEC-1, M1, and Schneider 2 (SL-2) cells were transiently cotransfected with the indicated endoglin reporter constructs and the KLF6 expression plasmid, and the transcriptional activity was measured 24 hours later by the luciferase reporter assay. KLF6-transfected–sample-fold induction is expressed relative to cells transfected with an empty vector, whose arbitrary value is 1. The means of 3 different experiments (± SD) are shown in each panel.

To determine the capacity of KLF6 to transactivate theendoglin promoter in a cell system devoid of endogenous KLF6, SL-2 Drosophila cells37 were used to assess KLF6 transactivation (Figure 4B). The induction by KLF6 ranged from 2.5- to 5-fold, and, interestingly, transactivation was preserved even in the pCD105(−50/+350) construct. These experiments established that KLF6 can transactivate the endoglinpromoter and that its responsive element is located within 50 bp upstream of the transcription start site.

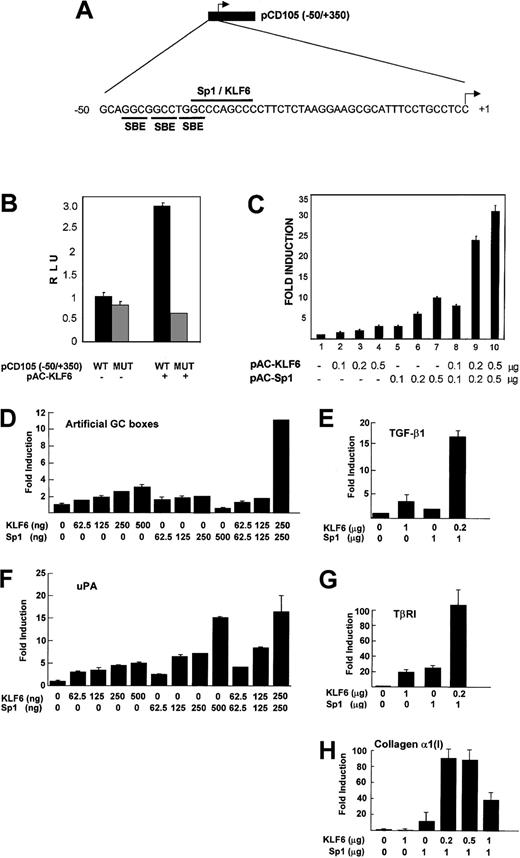

Functional cooperation between KLF6 and Sp1 in transactivating endoglin and key molecules regulating TGF-β activity

The region between −37/−29 bp of the endoglinpromoter contains an Sp1 consensus site (CCCAGCCC)33 that is required for the basal and TGF-β–induced transcription of endoglin.34 Like Sp1, KLF6 belongs to the family of Krüppel-like transcription factors39 that recognize a GC box motif in responsive promoters.50 To investigate whether KLF6 acts through the GC-rich motif at −37/−29 of the endoglin promoter (Figure 5A), a reporter containing a mutation in the consensus Sp1 site (CCC toTTT at −37) was transfected into SL-2 cells. As shown in Figure 5B, this mutation did not affect the basal promoter activity, but it did abolish transactivation by KLF6, indicating that KLF6 requires this site for endoglin transactivation.

Functional cooperation between KLF6 and Sp1 in transactivating endoglin and other GC box promoters.

(A) Diagram with the pCD105(−50/+350) reporter construct that contains the proximal region of the endoglin promoter. The sequence corresponding to the −50/+1 fragment includes the putative binding motifs for Smad (SBE), Sp1, and KLF6, as indicated. (B) Effect of mutation at −37/−29 of the endoglin promoter. Schneider-2 Drosophila cells were transfected with either the wild-type (WT) pCD105(−50/+350) reporter construct or the corresponding version containing a mutation in the GC box motif (MUT), in the presence or absence of the KLF6 expression vector(pPAC-KLF6), as indicated. Transcriptional activity was measured 24 hours later by the luciferase assay and was plotted as relative luciferase units (RLU). One of 4 representative experiments that yielded similar results is shown, with SD indicated. (C)Drosophila SL-2 cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg endoglin promoter-reporter construct pCD105(−50/+350), combined with the indicated amounts of expression plasmids for KLF6 and Sp1. Luciferase activity was measured after 24 hours. KLF6/Sp1-transfected–sample fold induction values are referred to the corresponding sample transfected only with an empty vector, whose arbitrary value is 1. Shown is 1 of 4 representative experiments whose results were similar, with the means (± SD shown). (D-H)Drosophila SL-2 cell cultures grown on 35-mm dishes were cotransfected with a combination of the indicated amounts ofSp1-pAC and KLF6-pAC expression vectors plus 500 ng (D). GC3-Luc (artificial promoter containing GC boxes). (E) phTG5luc (TGF-β1 promoter). (F)pUK-Luc (uPA promoter). (G) pTβRIP-Luc (−867 to −228; TβRI promoter). (H) pGL-Col 3 (collagen α1(I) promoter), as described in “Materials and methods.” After a 48-hour incubation, cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity in each lysate was determined and expressed as -fold increase. Each value represents the average ± SD from triplicate determinations. Each experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results, and representative results are shown. In all promoter contexts, a cooperative transactivation is seen between KLF6 and Sp1.

Functional cooperation between KLF6 and Sp1 in transactivating endoglin and other GC box promoters.

(A) Diagram with the pCD105(−50/+350) reporter construct that contains the proximal region of the endoglin promoter. The sequence corresponding to the −50/+1 fragment includes the putative binding motifs for Smad (SBE), Sp1, and KLF6, as indicated. (B) Effect of mutation at −37/−29 of the endoglin promoter. Schneider-2 Drosophila cells were transfected with either the wild-type (WT) pCD105(−50/+350) reporter construct or the corresponding version containing a mutation in the GC box motif (MUT), in the presence or absence of the KLF6 expression vector(pPAC-KLF6), as indicated. Transcriptional activity was measured 24 hours later by the luciferase assay and was plotted as relative luciferase units (RLU). One of 4 representative experiments that yielded similar results is shown, with SD indicated. (C)Drosophila SL-2 cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg endoglin promoter-reporter construct pCD105(−50/+350), combined with the indicated amounts of expression plasmids for KLF6 and Sp1. Luciferase activity was measured after 24 hours. KLF6/Sp1-transfected–sample fold induction values are referred to the corresponding sample transfected only with an empty vector, whose arbitrary value is 1. Shown is 1 of 4 representative experiments whose results were similar, with the means (± SD shown). (D-H)Drosophila SL-2 cell cultures grown on 35-mm dishes were cotransfected with a combination of the indicated amounts ofSp1-pAC and KLF6-pAC expression vectors plus 500 ng (D). GC3-Luc (artificial promoter containing GC boxes). (E) phTG5luc (TGF-β1 promoter). (F)pUK-Luc (uPA promoter). (G) pTβRIP-Luc (−867 to −228; TβRI promoter). (H) pGL-Col 3 (collagen α1(I) promoter), as described in “Materials and methods.” After a 48-hour incubation, cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity in each lysate was determined and expressed as -fold increase. Each value represents the average ± SD from triplicate determinations. Each experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results, and representative results are shown. In all promoter contexts, a cooperative transactivation is seen between KLF6 and Sp1.

Because KLF6 and Sp1 act through the same site in theendoglin promoter, we studied their individual and combined contributions to endoglin transcription in SL-2 cells, which lack endogenous KLF6 and Sp1. The cells were transfected with the proximal endoglin promoter reporter construct pCD105 (−50/+350) and KLF6, with or without Sp1 (Figure 5C). KLF6 and Sp1 transactivated the endoglin promoter in a dose-dependent manner; KLF6 induced endoglin from 2- to 5-fold above the basal activity (columns 1-4) (there was no further induction at concentrations higher than 0.5 μg; data not shown), whereas Sp1 stimulated transactivation from 3.5- to 10-fold across this same concentration range (columns 5-7). When both factors were cotransfected simultaneously, a cooperative effect could be observed, with transactivation increasing in a dose-dependent manner from 8-fold to 33-fold (columns 8-10).

Because the promoters of other key molecules regulating TGF-β activity also contain GC boxes and are responsive to KLF6 and Sp1 individually,37,40,45 we tested whether KLF6 and Sp1 also cooperated in the transactivation of these genes. Transient cotransfections of KLF6 ± Sp1 were performed in SL-2 cells using reporter plasmids representing the promoters of an artificial GC box reporter construct, GC3-Luc, TGF-β1, uPA, TβRI, and collagen α1(I). As shown in Figure 5D-H, KLF6 and Sp1 consistently cooperated in the transactivation of each of these GC box-containing promoters. As a control for specificity, KLF6 did not transactivate 2 different GC-less promoter constructs containing the TATA box of the prolactin (kindly provided by Dr Angel Corbı́) or the erythropoietin51 promoter (data not shown).

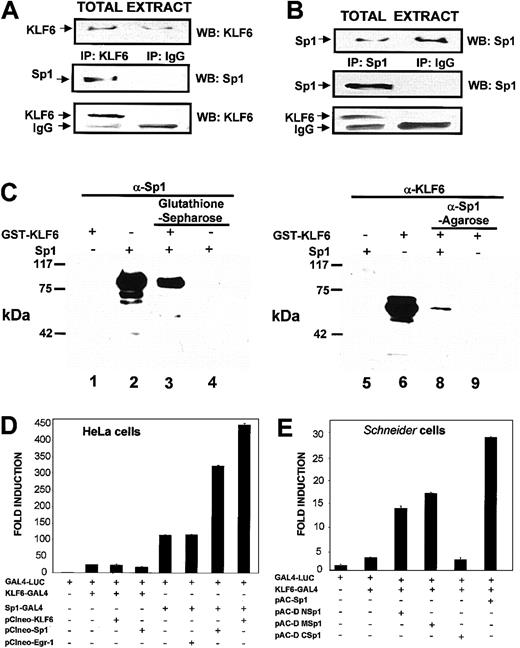

Physical interaction between Sp1 and KLF6

Transcriptional cooperation between Sp1 and KLF6 at the proximalendoglin promoter (Figure 5) raised the possibility that KLF6 and Sp1 are present within the same transcriptional complex. To test this directly in mammalian cells, transfections of KLF6 were carried out in COS-7 cells, which are a suitable system to overexpress exogenous proteins with high efficiency, and were followed by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Figure6A, transfected KLF6 coprecipitated with endogenous Sp1. Conversely, using an antibody against Sp1, KLF6 could be detected in the immunoprecipitate (Figure 6B).

Direct physical interaction between KLF6 and Sp1.

(A-B) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments in mammalian cells. COS-7 cells were transfected with the KLF6 expression vectorpCIneo-KLF6, and 24 hours later their total lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against KLF6 (A) or against Sp1 (B). Specific immune complexes were isolated using protein G-Sepharose, washed, and electrophoresed in 8% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose, and the specific antigens were detected with the indicated rabbit polyclonal antibody, followed by a secondary goat-antirabbit coupled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and an enhanced chemiluminescence assay. Arrows indicate the bands of transfected KLF6, endogenous Sp1, and immunoglobulin chain coming from the antibody used in the immunoprecipitation (IgG). As a control for specificity, a parallel immunoprecipitation with a nonimmune rabbit immunoglobulin (IP IgG) was performed. WB indicates Western blotting. (C) Pull-down experiments. A mixture of Sp1 plus GST-KLF6 was incubated with either glutathione-Sepharose beads or anti-Sp1 antibody-conjugated agarose beads at 4°C overnight, as described in “Materials and methods.” Proteins were precipitated, and eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with either anti-Sp1 or anti-KLF6 antibody. Lanes 1 to 4, probed with anti-Sp1 antibody; lanes 5 to 8, probed with anti-KLF6 antibody. Lanes 1 and 6, KLF6-GST; lanes 2 and 5, Sp1; lane 3, Sp1 preincubated together with KLF6 and precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose; lane 4, Sp1 incubated with glutathione-Sepharose without KLF6; lane 7, KLF6 preincubated together with Sp1 and precipitated with anti-Sp1 antibody; lane 8, KLF6 incubated with anti-Sp1 antibody without Sp1. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results, and representative results are shown. (D-E) Analysis of the interaction between Sp1 and KLF6 using the GAL4 one-hybrid system. (D) Sp1 and KLF6 functionally interact with each other when Sp1 is bound to DNA. HeLa cells were transfected with 0.5 μg GAL4-LUC reporter with or without 0.5 μg KLF6-GAL4, Sp1, KLF6, Sp1-GAL4, and Egr-1, as indicated. After 24 hours, luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the luciferase value obtained after transfection with GAL-4 LUC, which was given an arbitrary value of 1. (E) The C-terminal domain of Sp1 interacts with KLF6.Drosophila Schneider cells, SL-2, were transfected with 0.5 μg GAL4-LUC reporter with or without 0.5 μg GAL-4-KLF6 and 0.2 μg of full lengthpAC-Sp1 or deletion ΔΜ, ΔN, andΔC Sp1 mutants in the pAC vector. Luciferase activity was expressed as described for panel D.

Direct physical interaction between KLF6 and Sp1.

(A-B) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments in mammalian cells. COS-7 cells were transfected with the KLF6 expression vectorpCIneo-KLF6, and 24 hours later their total lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against KLF6 (A) or against Sp1 (B). Specific immune complexes were isolated using protein G-Sepharose, washed, and electrophoresed in 8% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose, and the specific antigens were detected with the indicated rabbit polyclonal antibody, followed by a secondary goat-antirabbit coupled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and an enhanced chemiluminescence assay. Arrows indicate the bands of transfected KLF6, endogenous Sp1, and immunoglobulin chain coming from the antibody used in the immunoprecipitation (IgG). As a control for specificity, a parallel immunoprecipitation with a nonimmune rabbit immunoglobulin (IP IgG) was performed. WB indicates Western blotting. (C) Pull-down experiments. A mixture of Sp1 plus GST-KLF6 was incubated with either glutathione-Sepharose beads or anti-Sp1 antibody-conjugated agarose beads at 4°C overnight, as described in “Materials and methods.” Proteins were precipitated, and eluted proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with either anti-Sp1 or anti-KLF6 antibody. Lanes 1 to 4, probed with anti-Sp1 antibody; lanes 5 to 8, probed with anti-KLF6 antibody. Lanes 1 and 6, KLF6-GST; lanes 2 and 5, Sp1; lane 3, Sp1 preincubated together with KLF6 and precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose; lane 4, Sp1 incubated with glutathione-Sepharose without KLF6; lane 7, KLF6 preincubated together with Sp1 and precipitated with anti-Sp1 antibody; lane 8, KLF6 incubated with anti-Sp1 antibody without Sp1. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results, and representative results are shown. (D-E) Analysis of the interaction between Sp1 and KLF6 using the GAL4 one-hybrid system. (D) Sp1 and KLF6 functionally interact with each other when Sp1 is bound to DNA. HeLa cells were transfected with 0.5 μg GAL4-LUC reporter with or without 0.5 μg KLF6-GAL4, Sp1, KLF6, Sp1-GAL4, and Egr-1, as indicated. After 24 hours, luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the luciferase value obtained after transfection with GAL-4 LUC, which was given an arbitrary value of 1. (E) The C-terminal domain of Sp1 interacts with KLF6.Drosophila Schneider cells, SL-2, were transfected with 0.5 μg GAL4-LUC reporter with or without 0.5 μg GAL-4-KLF6 and 0.2 μg of full lengthpAC-Sp1 or deletion ΔΜ, ΔN, andΔC Sp1 mutants in the pAC vector. Luciferase activity was expressed as described for panel D.

These findings identified KLF6 and Sp1 within the same immunoprecipitate but did not establish their direct interaction. The latter was examined by performing direct in vitro GST pull-down experiments using recombinant GST-KLF6 and recombinant Sp1. As shown in Figure 6C, KLF6 and Sp1 bound directly to each other, whether using glutathione-Sepharose affinity with or without Sp1 followed by Sp1 Western blot analysis or using the reverse combination of anti-Sp1 agarose followed by KLF6 Western blot analysis. GST alone did not bind Sp1 protein (data not shown).

We used the GAL4-LUC one-hybrid reporter system as another means of demonstrating a direct and functional interaction between KLF6 and Sp1. In this system, a fusion protein was generated in which either KLF6, Sp1, or Sp1-deletion mutants were expressed in frame 5′ of the GAL4 DNA-binding domain, which was then cotransfected with a GAL4-responsive reporter. Transient transfections in HeLa cells showed that when KLF6-GAL4 interacted with the promoter through its GAL4 DNA-binding domain, there was no additive effect on transactivation of either wild-type KLF6 or Sp1 (Figure 6D). However, when Sp1-GAL4 interacted with the GAL4-responsive promoter, marked cooperation was observed if either Sp1 or KLF6 was cotransfected. Interestingly, in contrast to the results in HeLa cells, Sp1 markedly cooperated with KLF6-GAL4 transactivation in Drosophila Schneider cells (Figure 6E). Therefore, we used this system to map the domain(s) of Sp1 required to cooperate with KLF6 transactivation. The C-terminal domain of Sp1 contains the DNA-binding domain through the Zn+2 fingers, whereas M and N domains (middle and N-terminal) contain 2 glutamine-rich domains involved in transactivation.43Deletion constructs of Sp1 in the pAC vector were generated for expression in Drosophila that lacked either the N or the M region, or the C-terminal of the protein, and were assessed for their ability to cooperate with KLF6-GAL4–mediated transactivation. As shown in Figure 6E, some cooperativity was preserved when either the N or the M region was deleted, albeit less than that observed with full-length Sp1 and KLF6-GAL4. However, a complete loss of cooperation with KLF6 occurred after deletion of the C-terminal domain (amino acids 552-778), representing the DNA binding domain. This interaction between the C-terminal domains of 2 Krüppel-like factors has been reported previously for erythroid Krüppel-like factor (EKLF) and others.52 53

Furthermore, our data suggest the interaction does not require that both factors be bound to DNA. In the GAL4 system we used, none of the Sp1 constructs was capable of binding directly to the GAL4-responsive reporter DNA.

Discussion

This study emphasizes the potential of KLF6 to respond to vascular injury by stimulating endoglin gene expression. Furthermore, coexpression of Sp1 creates the potential for a cooperative transactivation of endoglin and of other key molecules that regulate TGF-β activity and extracellular matrix accumulation. Therefore, these findings point to a complex transcriptional event, involving at least 2 Krüppel-like transcription factors, that plays a central role in vascular repair. In an in vivo rat model of arterial injury, KLF6 and subsequently endoglinare induced within 12 to 24 hours after injury. Similarly, in a porcine model of coronary artery injury, TGF-β andendoglin expression are up-regulated after balloon injury,35 which results in increased TGF-β signaling and vascular repair.54 We have now explored this process in a culture model of endothelial denudation. The findings demonstrate that KLF6 is rapidly induced and translocated to nuclei after injury, followed by the induction of endoglin.

Transcriptional induction of endoglin during vascular repair therefore reflects several possible activities of KLF6. First, TGF-β is induced after injury in response to KLF6,39 which increases endoglin transcription mediated by Smads and Sp1 transcription factors, as we reported.33,34 Second, we demonstrate here that KLF6 directly stimulates endoglintranscription. Third, functional cooperation between KLF6 and Sp1 may induce TGF-β1 and an entire family of molecules involved in tissue repair, all of which have GC box motifs in their promoters—the cognate recognition sequence for KFL6 and Sp1. Through this cooperation KLF6 may switch the function of Sp1 from promoting constitutive transcription to participating in inducible transcription. The functional interaction between Sp1 and KLF6 likely involves their direct physical interaction, as shown by coimmunoprecipitation experiments, and is further supported by in vitro GST pull-down assays using recombinant KLF6 and Sp1. Moreover, using a GAL4 one-hybrid system, we demonstrate that functional interaction between KLF6 and Sp1 requires the C-terminal domain of Sp1. Previous studies55,56 provide ample evidence that Krüppel-like factors can interact with one another, typically involving the DNA binding domains.52,53,57 58

KLF6 is induced as an immediate-early gene in hepatic stellate cells, the key cell regulating extracellular matrix production during tissue repair.37 In general, KLF6 is a labile factor in vitro that disappears quickly after withdrawal of the appropriate stimulus, which may include PMA and serum,39or, as in the experiments described herein, after mechanical injury in cultured endothelial cells. Egr-1, another zinc finger early-response gene in vitro, is induced in endothelial cells in a similar pattern after injury.59 However, our data suggest that the induction of endoglin by KLF6 is not generalized to all zinc finger proteins because Egr-1 does not promoteendoglin expression.

KLF6 and Sp1 are dependent on the GC-rich consensus motif at −37 ofendoglin promoter, as evidenced by loss of transactivation when this motif is mutated or deleted. We have also demonstrated direct binding between recombinant KLF6 and the −50/−29 region and the concurrent presence of Sp1 and KLF6 in protein-DNA complexes on theendoglin promoter (data not shown). Interactions between KLF6 and Sp1 have previously been suggested in studies of theTβRI and TβRII promoters based on transfection studies.40 Similarly, KLF6 may cooperate with other coactivators in binding to the proximal GC box of theleukotriene C4 synthase promoter.60Neither of these other studies, however, has provided evidence of either physical interaction or coimmunoprecipitation in nuclear extracts, as we demonstrate here.

Our data suggest a model whereby Sp1 and KLF6 have similar DNA-binding properties but different biologic roles in vascular injury. Both proteins may potentially bind DNA at the same Sp1 consensus in theendoglin promoter, CCCAGCCC (−37/−29). However, thoughKLF6 is rapidly induced on injury, Sp1 may bind this site in normal tissue, where it is crucial for basal expression ofendoglin.34 Thus, after injury, as mimicked by endothelial denudation, KLF6 mRNA and then protein are induced rapidly, followed by nuclear translocation. Our findings further suggest that nuclear KLF6 may hetero-oligomerize with Sp1, leading to a marked increase in transcription of endoglin and other injury-related genes. This conclusion is supported by the delayed increase in endoglin transcription until after KLF6 is induced. The delay may also be attributed to the additional time required for translation and translocation of endoglin to the cell surface, where it is active.

In the absence of endogenous Sp1, as in Drosophila SL-2 cells, KLF6 can replace Sp1 for basal transactivation of theendoglin promoter. This result is in agreement with the transactivation of TGF-β1 promoter by KLF6 inDrosophila, in contrast to its effects on theTβRI and TβRII genes, which occurs only in the presence of Sp1.40 Collectively, these findings suggest that in the normal vascular wall, Sp1 might be primarily responsible for basal endoglin transcription.34It seems likely that other transcription factors or coactivators also contribute to endoglin induction in vivo, in particular Smads. Thus, future studies will explore their potential interactions with the GC box binding proteins KLF6 and Sp1 in hope of reconstructing all the key components required for endoglin expression in normal and diseased tissue. Moreover, these findings could have important implications for understanding endoglin dysregulation in genetic diseases such as HHT1.

We thank Dr Angel Corbı́ for stimulating discussions, Dr Carlos Rius for plasmids, Drs S. Hayashi and Y. Suzuki for technical assistance, and Dr Pedro Lastres for flow cytometry analysis.

Supported by grants from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologı́a (SAF2000-0132) (C.B.), Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, the National Institutes of Health (DK37340) (S.L.F), and the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Science and Technology Agency of Japan (S.K.). T.S.-E. and F.S.-R. are recipients of fellowships from Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid. M.P.C. is supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds.

L.M.B. and T.S.-E. contributed equally to this paper.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Luisa M. Botella, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, CSIC, Velázquez, 144, 28006 Madrid, Spain; e-mail: cibluisa@cib.csic.es.