Estrogen replacement therapy has been associated with reduction of cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women, though the mechanism for this benefit remains unclear. Here we show that at physiological concentrations estrogen activates the anandamide membrane transporter of human endothelial cells and leads to rapid elevation of calcium (apparent within 5 minutes) and release of nitric oxide (within 15 minutes). These effects are mediated by estrogen binding to a surface receptor, which shows an apparent dissociation constant (Kd) of 9.4 ± 1.4 nM, a maximum binding (Bmax) of 356 ± 12 fmol × mg protein−1, and an apparent molecular mass of approximately 60 kDa. We also show that estrogen binding to surface receptors leads to stimulation of the anandamide-synthesizing enzyme phospholipase D and to inhibition of the anandamide-hydrolyzing enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase, the latter effect mediated by 15-lipoxygenase activity. Because the endothelial transporter is shown to move anandamide across the cell membranes bidirectionally, taken together these data suggest that the physiological activity of estrogen is to stimulate the release, rather than the uptake, of anandamide from endothelial cells. Moreover, we show that anandamide released from estrogen-stimulated endothelial cells, unlike estrogen itself, inhibits the secretion of serotonin from adenosine diphosphate (ADP)–stimulated platelets. Therefore, it is suggested that the peripheral actions of anandamide could be part of the molecular events responsible for the beneficial effects of estrogen.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death in postmenopausal women in developed countries, suggesting that estrogen (17β-estradiol [E2]) deficiency may play a causative role.1 A positive effect of E2 on plasma lipids and lipoproteins, endothelium-dependent vasodilation, and intimal hyperplasia has been documented 2 and is thought to contribute to the cardioprotective effects observed in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen replacement therapy. In addition, platelets have a well-established role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases.3 They show an intracellular E2 receptor4 and are regulated by E2.1 The mechanisms by which E2 influences coronary arteries and protects blood vessels against atherosclerotic development remain unclear, but recent evidence suggests that the rapid effects of E2 on vascular reactivity depend on the activation of an estrogen surface receptor in endothelial cells, followed by calcium-dependent release of nitric oxide (NO).5,6 Endothelial cells have a selective anandamide (arachidonoylethanolamide [AEA]) membrane transporter (AMT), which is activated by NO.7 AEA is a prominent member of a group of endogenous lipids that include amides, esters, and ethers of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and are collectively termed endocannabinoids.8,9 AEA is released from membraneN-arachidonoyl-phosphatidyl-ethanolamines of depolarized neurons through phospholipase D10 and mimics the psychotropic and analgesic effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol by binding to central (CB1) and peripheral (CB2) cannabinoid receptors.10,11 AEA and the other endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), have cardiovascular actions that include a profound decrease in blood pressure and heart rate,12 platelet activation,13,14 vasodilation during advanced liver cirrhosis,15 and control of migration of hematopoietic cells.16 A role for AEA and 2-AG as cardiovascular modulators is also suggested by the observation that endothelial cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, and platelets release one or both endocannabinoids.12 The many central and peripheral actions of AEA, and its ability to reduce pain signals at sites of injury17 and to regulate the immune response,18 are terminated by cellular uptake through AMT,19 followed by degradation to ethanolamine and arachidonic acid by the enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH).20 Recently, cross-talk between progesterone and the peripheral endocannabinoid system has been demonstrated in human lymphocytes.21 Therefore, we sought to investigate whether E2 might regulate AEA metabolism in endothelial cells, thus implying that this endocannabinoid could contribute to the beneficial effects of E2 on the cardiovascular system.

Materials and methods

Materials

Chemicals were of the purest analytical grade. AEA, ethanolamine, arachidonic acid, 17β-estradiol (E2), 17β-estradiol 6-(O-carboxymethyl) oxime conjugated to bovine serum albumin (E2-BSA), 17α-estradiol (epiestradiol [epi-E2]), hydrocortisone (cortisol), tamoxifen (TMX),Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Arachidonoyl-trifluoromethyl-ketone (ATFMK) andN-(4-hydroxyphenyl) arachidonoylamide (AM404) were from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA). Ethyleneglycol-bis(β-aminoethyl)-N, N, N′,N′-tetra-acetoxymethyl ester (EGTA-am), capsazepine (N-[2-(4-chloro-phenyl)ethyl]-1,3,4,5-tetrahydro-7,8-dihydroxy-2H-2-benzazepine-2-carbothioamide [CAPS]), capsaicin, suramin, ST638 (α-cyano-(3-ethoxy-4-hydroxy-5-phenylthiomethyl) cinnamide), and phospholipase D from Streptomyces chromofuscus (76 U/mg protein, 1 U hydrolyzing 1 μmol substrate per minute) were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). HU-210 was from Alexis (Läufelfingen, Switzerland). Bovine recombinant endothelial nitric oxide synthase (2 U/mg protein, 1 U generating 1 nmol product per minute) was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). ICI182780 was from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, United Kingdom).N-piperidino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-3-pyrazole-carboxamide (SR 141716) and N-[1(S)-endo-1,3,3-trimethyl bicyclo [2.2.1] heptan-2-yl]-5-(4-chloro-3-methylphenyl)-1-(4-methylbenzyl)-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (SR 144528) were kind gifts from Sanofi Recherche (Montpellier, France). Cannabidiol (CBD) and soybean lipoxygenase-1 (200 U/mg protein, 1 U oxygenating 1 μmol substrate per minute) were kind gifts from Drs M. Van der Stelt and G. van Zadelhoff (Utrecht University, The Netherlands), respectively. Abnormal-CBD was kindly donated by Prof B. Martin (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA). 1-[2-amino-5-(2,7-dichloro-6-hydroxy-3-oxy-9-xanthenyl)-phenoxy]-2-[2-amino-5-methyl-phenoxy]-ethane-N, N, N′, N′-tetraacetoxy-methyl ester (Fluo-3 am) was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). [3H]AEA (223 Ci/mmol [8 251 GBq/mmol]), [3H]arachidonic (eicosatetraenoic) acid (80 Ci/mmol [2 960 GBq/mmol]), [3H]ADP (32.5 Ci/mmol [1 202.5 GBq/mmol]), [3H]17β-estradiol (80 Ci/mmol [2 960 GBq/mmol], [3H]E2), and [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine (25.5 Ci/mmol [943.5 GBq/mmol], [3H]5-HT) were from NEN DuPont de Nemours (Cologne, Germany). L-[2,3,4,5-3H]arginine (64 Ci/mmol [2368 GBq/mmol]), [1-14C]linoleic (octadecadienoic) acid (56 mCi/mmol [2072 MBq/mmol]) and 1,2-dioleoyl-3-phosphatidyl[2-14C]ethanolamine (55 mCi/mmol [2035 MBq/mmol]) were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). Rabbit antiestrogen receptor α (ERα) and goat antiestrogen receptor β (ERβ) polyclonal antibodies, ERβ competing peptide, and donkey antigoat alkaline phosphatase conjugate were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Goat antirabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugate was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Richmond, CA).

Endothelial cell culture and coculture with human platelets

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from BioWhittaker and were cultured in 75-cm2 flasks at a density of 2500/cm2 in EGM-2 Bulletkit medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD), as reported.7 For coculture experiments, HUVECs (1 × 106/test) at the fourth to fifth passages were treated with 100 nM E2, E2-BSA, TMX, or vehicle (methanol) for 30 minutes in serum-free medium, followed by incubation in complete medium for the indicated times. Then cells were washed and seeded in 6-well polystyrene Falcon plates (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA) containing fresh serum-free medium and were cocultured for 10 minutes with human platelets (5 × 109/test), prepared as reported.14 For the [3H]5-HT release experiments, platelets (5 × 109 in 500 μL Hanks balanced salt solution; Flow Laboratories, Herts, United Kingdom) were preloaded with [3H]5-HT (1 μCi [0.037 MBq]) for 15 minutes at 37°C and then were centrifuged at 1000g for 15 minutes, and the pellet was resuspended in serum-free EGM-2 Bulletkit medium, essentially as reported.14 HUVECs and platelets were kept separated by a 0.4-μm Falcon cell culture insert (PET track-etched membrane; Becton Dickinson). Immediately after coincubation, platelets were activated for 2 minutes with 1 μM ADP,1 and the amount of [3H]5-HT released was measured in an LKB1214 Rackbeta scintillation counter (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), as described.14 In some experiments, partially purified anandamide hydrolase (fatty acid amide hydrolase, FAAH; 5000 U/mg, 1 U hydrolyzing 1 pmol substrate per minute) was added to the culture medium (100 U/mL), and a new aliquot was added every hour. This FAAH was prepared from human lymphoma U937 cells (100 × 106) by differential centrifugation and freezing-thawing, as the 105 000g supernatant recently described.22 In other experiments, AEA, SR141716, SR144528, CBD, CAPS, arachidonic acid, or ethanolamine was added at the indicated concentrations to platelets alone (5 × 109/test) that had been preloaded with [3H]5-HT and then activated with 1 μM ADP under the same experimental conditions as those used for platelets cocultured with HUVECs. In addition, in this case, the release of [3H]5-HT from activated platelets was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Binding studies and Western blot analysis

The isolation of nuclear pellets and nuclei-free cell membrane pellets from HUVECs was performed as reported.23 These 2 fractions were used in rapid filtration assays with [3H]E2 as described,24 and the binding data were elaborated through nonlinear regression analysis, using the Prism 3 program (GraphPAD Software for Science, San Diego, CA). In all binding experiments, nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM “cold” E2.24 For Western blot analysis, nuclear or cell membrane homogenates (10 or 20 μg/lane, respectively) were prepared as described24 and were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 12%), followed by electrotransfer to 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filters (Bio-Rad), as reported.25 Rainbow molecular weight markers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were bovine serum albumin (66 kDa) and ovalbumin (46 kDa). Filters were immunoreacted with anti-ERα or anti-ERβ polyclonal antibodies and were diluted 1:200 using goat antirabbit or donkey antigoat alkaline phosphatase conjugate (diluted 1:2000) as second antibody, respectively.24 The specificity of the immunoreactive bands was assessed by preincubating anti-ERβ antibody (10 μg/mL) with the ERβ competing peptide (70 μM), as reported.25 Densitometric analysis of filters was performed by means of a Floor-S Multi-Imager, equipped with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Determination of anandamide uptake and release

The uptake of [3H]AEA by intact HUVECs through the anandamide membrane transporter (AMT) was studied as described.7 Cell suspensions (1 × 106cells/test) were incubated for different time intervals, at 37°C, with 100 nM [3H]AEA, and AMT activity was expressed as picomole AEA taken up per minute per milligram protein. Incubations (15 minutes) were also carried out with different concentrations of [3H]AEA, in the range of 0 to 1000 nM to determine apparent Km and Vmax of the uptake by Lineweaver-Burk analysis.7 The effect of different compounds on AEA uptake (15 minutes) was determined by adding each substance directly to the incubation medium at the indicated concentrations. The ability of HUVECs (5 × 106/test), untreated or pretreated with E2 and related compounds for 4 hours as described above, to release AEA into the culture medium was determined by loading cells with [3H]AEA (1 μCi/106[0.037 MBq/106] cells) for 10 minutes14 in the presence of 10 μM ATFMK, then washing and measuring at different incubation times the radioactivity of the culture medium containing 10 μM ATFMK.15 The identity of AEA was ascertained by reverse-phase–high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), as reported,26 yielding chromatograms like those shown in Figure 3C. In some experiments, HUVECs (1 × 106cells/test) were preloaded with 100 μM cold AEA for 30 minutes and were washed, and then their ability to take up 100 nM [3H]AEA from the culture medium was determined as described above. A large-scale experiment was performed by incubating HUVECs (10 × 106/test) for 1 hour at 37°C with [3H]arachidonic acid (10 μCi/test [0.37 MBq/test]) in serum-free culture medium, containing or not containing 100 nM E2, and then washing and resuspending the cells in complete culture medium with 10 μM ATFMK for an additional 3 hours at 37°C. Membrane lipids were extracted as described previously,26 and radioactivity was measured in lipid extracts and culture media by liquid scintillation counting. Cell viability after each treatment was checked with trypan blue and was found to be higher than 90%.

Enzymatic assays

FAAH (E.C. 3.5.1.4) activity was assayed in HUVEC extracts by measuring the release of [3H]arachidonic acid from [3H]AEA, using RP-HPLC.26 Nitric oxide synthase (E.C. 1.14.13.39; NOS) was assayed by measuring the conversion of [3H]arginine into [3H]citrulline.27 15-lipoxygenase (E.C. 1.13.11.12; 15-LOX) was assayed by measuring the oxidation of [3H]linoleic acid to 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE).28 Phospholipase D (E.C. 3.1.4.4; PLD) was assayed by measuring the release of [14C]ethanolamine from 1,2-dioleoyl-3-phosphatidyl-[2-14C]ethanolamine.29The activities of cellular FAAH, NOS, 15-LOX, and PLD were within the linearity range of calibration curves drawn with partially purified FAAH (0-200 U/mg protein), purified NOS (0-250 mU/mg protein), purified soybean lipoxygenase-1 (0-10 mU/mg protein), 15-LOX,30 and purified PLD (0-1 mU/mg protein), respectively.

Nitrite release and calcium levels in endothelial cells

Generation of NO by endothelial cells (5 × 106cells/test) was determined by measuring accumulation after 15 minutes of the stable end product nitrite (NO) in culture supernatants.7 Nitrite levels were within the linearity range of calibration curves made from a solution of sodium nitrite. Cytoplasmic free calcium was measured using the fluorescent Ca++ indicator Fluo-3 am in HUVECs (5 × 106 cells/test) treated with different compounds (or vehicle in the controls) for 5 minutes.24

Determination of cAMP and IP3 levels in human platelets and binding of [3H]ADP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels in extracts of platelets (5 × 109/test) were determined by the Cayman Chemical cAMP Enzyme Immunoassay kit (Alexis), as reported.14 Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) content in extracts of platelets (5 × 109/test) was measured by the IP3 [3H]Radioreceptor Assay kit (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA), as reported.14 The effect of AEA on the binding of 500 pM [3H]ADP to membrane fractions prepared from human platelets (10 × 1010/test), as described,14was determined by rapid filtration assays.24 Unspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM ADP.24

Statistical analysis

Data reported in this paper are the means ± SD of at least 3 independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. The initial velocities and the half-times of the in and out flux of AEA through AMT were calculated by fitting the time-course data to a sum of 2 exponential relaxation processes through MATLAB 5.2 software (The Mathworks). Statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test, elaborating experimental data by means of the InStat 3 program (GraphPAD Software for Science).

Results

Stimulation of AMT, nitric oxide, and calcium in endothelial cells by E2

HUVECs accumulate [3H]AEA through selective AMT showing an apparent Km of 190 ± 10 nM and an apparent Vmax of 45 ± 3 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1.7 In vitro treatment of HUVECs with E2 enhanced AMT activity in a dose-dependent manner, as did E2 conjugated to BSA (Figure1A). AMT activation by E2 or E2-BSA reached statistical significance (P < .05) at 10 nM and an approximately 4-fold maximum at 100 nM. Under the latter conditions, kinetic analysis of [3H]AEA uptake by AMT showed an apparent Km of 200 ± 10 nM and Vmax of 225 ± 15 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1. Instead, 17α-estradiol (epi-E2), the inactive epimer of E2,31 or cortisol, which acts at glucocorticoid receptors,21 were ineffective at up to 200 nM concentration. The activation of AMT by 100 nM E2 or E2-BSA was further investigated in time-course experiments showing that either compound was effective (P < .05) 30 minutes after HUVEC treatment and reached a maximum at 4 hours (not shown). Treatment of HUVECs with E2 or E2-BSA also enhanced NO release (Figure 1B) and intracellular calcium (Figure1C) dose dependently; the calcium increase was apparent earlier (5 minutes) than the NO increase (15 minutes). NO and calcium increases reached statistical significance (P < .05) at an E2 or E2-BSA concentration of 10 nM and a 4- to 5-fold maximum at 100 nM. Instead, treatment of HUVECs with epi-E2 or cortisol up to 200 nM was ineffective (Figure 1B-C).

Effect of E2 and related compounds on AMT activity, NO release, and calcium levels in HUVECs.

Dependence of AMT activity (A), NO release (B), and intracellular calcium levels (C) on the concentration of E2, E2-BSA, epi-E2, or cortisol. Values are reported as means ± SD. In all panels, *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control (P > .05 in all other cases).

Effect of E2 and related compounds on AMT activity, NO release, and calcium levels in HUVECs.

Dependence of AMT activity (A), NO release (B), and intracellular calcium levels (C) on the concentration of E2, E2-BSA, epi-E2, or cortisol. Values are reported as means ± SD. In all panels, *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control (P > .05 in all other cases).

Binding of E2 to endothelial cell membranes

HUVEC cell membranes were found to bind [3H]E2 with saturation curves like those shown in Figure2A. From these curves, an apparentKd of 9.4 ± 1.4 nM and a Bmax of 356 ± 12 fmol × mg protein−1 could be calculated. TMX (100 nM), an estrogen receptor antagonist,5,6 fully displaced E2 from its membrane receptor, whereas 100 nM ICI182780, a selective antagonist of nuclear estrogen receptors,5,6 was ineffective (Figure 2A). E2 was able to bind to a nuclear receptor in HUVECs through a saturable process (not shown) withKd and Bmax values of 3.4 ± 0.3 nM and 2067 ± 37 fmol × mg protein−1. TMX and ICI182780 (each used at 100 nM) fully displaced this binding. Furthermore, cold E2 (1 μM) fully displaced [3H]E2 from membrane and nuclear receptors. Interestingly, theKd value of the HUVEC nuclear receptor for E2 is close to that of authentic estrogen receptor β (ERβ), whereas ERα has a Kd approximately 10-fold lower.23 Consistent with the binding data, Western blot analysis showed that anti-ERβ, but not anti-ERα, antibodies recognized a single immunoreactive band in HUVEC extracts (Figure 2A inset and data not shown), with the expected molecular mass for ERβ (approximately 60 kDa).23,24 This band disappeared when anti-ERβ antibodies were preincubated with the competing peptide (not shown). Densitometric analysis of filters like those shown in Figure 2A (inset) suggested that the level of membrane receptors was approximately 6-fold lower than that of nuclear receptors. Taken together with the binding data, it can be suggested that HUVECs possess a nuclear ERβ that has a higher affinity for E2 and is expressed at higher level than the estrogen surface receptor (ESR). This hypothesis is corroborated by the transcription of the gene of ERβ, but not of ERα, reported in HUVECs.5

Binding of E2 to HUVECs and modulation of the effects of E2 by various compounds.

(A) Saturation curves of the binding of [3H]E2 to cell membranes, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or 100 nM ICI182780. Vertical bars represent SD values. (Inset) Western blot analysis of nuclear (N) and membrane (M) homogenates (10 and 20 μg/lane, respectively), reacted with anti-ERβ antibodies. Molecular mass markers are shown on the right side. (B) Effect of TMX, ICI182780, or HU-210 (100 nM each), of SR141716, CBD, or CAPS (2 μM each), ofl-NAME (400 μM) or of EGTA-am (50 μM) on the activation of AMT by 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA (100% = 25 ± 3 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1). (C) Effect of the same treatments discussed in panel B on the release of NO and the intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) of HUVECs. Values are reported as means ± SD. In all panels, *P < .01 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).

Binding of E2 to HUVECs and modulation of the effects of E2 by various compounds.

(A) Saturation curves of the binding of [3H]E2 to cell membranes, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or 100 nM ICI182780. Vertical bars represent SD values. (Inset) Western blot analysis of nuclear (N) and membrane (M) homogenates (10 and 20 μg/lane, respectively), reacted with anti-ERβ antibodies. Molecular mass markers are shown on the right side. (B) Effect of TMX, ICI182780, or HU-210 (100 nM each), of SR141716, CBD, or CAPS (2 μM each), ofl-NAME (400 μM) or of EGTA-am (50 μM) on the activation of AMT by 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA (100% = 25 ± 3 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1). (C) Effect of the same treatments discussed in panel B on the release of NO and the intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) of HUVECs. Values are reported as means ± SD. In all panels, *P < .01 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).

Modulation of E2-induced activation of AMT by various compounds

The activation of AMT by E2 was further investigated by using the agonists, antagonists, and inhibitors listed in Table1. The effect of 100 nM E2 or E2-BSA was fully inhibited by 100 nM TMX, whereas at the same concentration ICI182780 had no effect (Figure 2B). HUVECs express a functional CB1 receptor,7,37 and 100 nM HU-210 increased AMT activation to approximately 160% of the estrogen-treated cells—that is, approximately 700% of the untreated controls (Figure 2B). Remarkably, 100 nM HU-210 alone has been shown to increase AMT activity in HUVECs only to approximately 140% of the untreated controls.7Conversely, SR141716, CBD, and CAPS did not affect AMT activation by 100 nM E2 or E2-BSA when used at 2 μM (Figure 2B). Furthermore, abnormal-CBD and capsaicin were ineffective up to 2 μM (not shown). AMT activation by 100 nM E2 or E2-BSA was also abolished by 400 μMl-NAME or by 50 μM EGTA-am, a cell-permeant calcium chelator (Figure 2B).24 On the other hand, 100 nM TMX fully inhibited the enhancement of NO release and calcium induced by 100 nM E2, whereas 100 nM HU-210 further increased NO release to 160% of the E2-treated cells (Figure 2C). ICI182780 (100 nM), SR141716, CBD, CAPS, abnormal-CBD, and capsaicin (each used at 2 μM) were ineffective on NO and calcium levels (Figure 2C and data not shown). Moreover, 400 μM l-NAME prevented E2-induced NO release without affecting calcium levels, whereas 50 μM EGTA-am fully prevented calcium elevation and reduced NO release to 45% of the E2-treated cells (Figure 2C).

AMT of endothelial cells is a bidirectional transporter

HUVECs preloaded with [3H]AEA were able to release it in the culture medium in a time-dependent manner (Figure3A). Release of [3H]AEA at 20 minutes was fully prevented by 10 μM AM404, and kinetic analysis of the release process showed a t½ of 5 ± 1 minute and an initial rate (v0) of 20 ± 2 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1. The same kinetic analysis of the time-course of the [3H]AEA uptake yieldedt½ = 5 ± 1 minute and v0 = 23 ± 2 pmol × minute−1mg protein−1, confirming our previous data.7 E2 and E2-BSA dose dependently enhanced [3H]AEA release from HUVECs, reaching statistical significance (P < .05) at 5 nM and an approximately 5-fold maximum at 100 nM, whereas epi-E2 or cortisol were ineffective at concentrations up to 200 nM (Figure 3B). RP-HPLC analysis demonstrated that the released compound was indeed AEA (Figure 3C). From calibration curves (Figure 3C, inset), it could be estimated that 100 nM E2 led to an AEA release of 1500 ± 150 fmol/106 cells, compared with 300 ± 30 fmol/106 cells of controls. Table2 shows that 100 nM TMX prevented E2-stimulated release of AEA from HUVECs, whereas 100 nM HU-210 increased it to 160% of the E2-treated cells. Again SR141716, CBD, CAPS, abnormal-CBD, and capsaicin (each used at 2 μM) were ineffective (Table 2 and data not shown). Instead, stimulation of AEA release by 100 nM E2 was fully prevented by 10 μM AM404, 400 μMl-NAME, or 50 μM EGTA-am (Table 2).

Transport of AEA across HUVEC membranes.

(A) Time-course of the uptake of [3H]AEA from the extracellular space (movement in) or of the release of [3H]AEA from endothelial cells preloaded with [3H]AEA (movement out), in the presence of 10 μM ATFMK (100% = 420 ± 40 or 320 ± 30 fmol/106 cells, for the in-and-out transport, respectively). # designates the effect of 10 μM AM404 on the release of [3H]AEA at 20 minutes. (B) Dependence of the release of [3H]AEA on the concentration of E2, E2-BSA, epi-E2, or cortisol. (C) Representative chromatogram of the lipids extracted from the culture media of HUVECs, untreated (control), or treated with 100 nM E2 for 4 hours. The peaks coeluted with authentic AEA and their areas were within the linearity range of calibration curves (inset). Values are reported as means ± SD. In panel B, *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control (P > .05 in all other cases).

Transport of AEA across HUVEC membranes.

(A) Time-course of the uptake of [3H]AEA from the extracellular space (movement in) or of the release of [3H]AEA from endothelial cells preloaded with [3H]AEA (movement out), in the presence of 10 μM ATFMK (100% = 420 ± 40 or 320 ± 30 fmol/106 cells, for the in-and-out transport, respectively). # designates the effect of 10 μM AM404 on the release of [3H]AEA at 20 minutes. (B) Dependence of the release of [3H]AEA on the concentration of E2, E2-BSA, epi-E2, or cortisol. (C) Representative chromatogram of the lipids extracted from the culture media of HUVECs, untreated (control), or treated with 100 nM E2 for 4 hours. The peaks coeluted with authentic AEA and their areas were within the linearity range of calibration curves (inset). Values are reported as means ± SD. In panel B, *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control (P > .05 in all other cases).

The ability of AMT to transport AEA across membranes bidirectionally was further investigated by preloading HUVECs with cold AEA and measuring the uptake of [3H]AEA from the extracellular medium. Obviously, a reversible carrier must be able to bind the solute on both sides of the membrane, and a high concentration of the solute on one side should favor the exchange of intracellular with extracellular solute molecules, leading to the so-calledtrans effect of flux coupling.19 Such atrans effect experiment demonstrated that indeed HUVECs were able to accumulate [3H]AEA at a rate of 15 ± 2 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1compared with 25 ± 3 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1 of the controls. Furthermore, in a large-scale experiment, HUVECs, untreated or treated with E2 and related compounds, released different amounts (between 5% and 25%) of the incorporated [3H]arachidonic acid (approximately 50% of that supplied in all cases); the remaining part was found in the membrane lipids. RP-HPLC analysis of these lipids26 did not find free arachidonate, suggesting that it was incorporated into the different (phospho)lipid classes, in line with a recent report.38RP-HPLC of the lipids extracted from the culture medium showed that radioactivity release was due to a compound that eluted with the same retention time (2.2 minutes) of AEA (Figure 3C), whereas no peaks corresponding to 2-AG (2.9 minutes) or to arachidonic acid (3.4 minutes) could be detected. The release of [3H]AEA from HUVECs preloaded with [3H]arachidonate (not shown) was superimposable to that of cells preloaded with [3H]AEA itself (Figure 3B; Table 2). Suramin and ST638 reduced to 35% to 40% the release of [3H]AEA induced by 100 nM E2 from [3H]arachidonate-loaded HUVECs, at concentrations that inhibited the target enzyme (Table 3).

E2 modulates the enzymes responsible for AEA metabolism in endothelial cells

Treatment of HUVECs with 100 nM E2 or E2-BSA decreased FAAH activity (down to 20% of the controls) and increased the activity of NOS, 15-LOX, and PLD (by 400%, 320%, and 275% of the controls, respectively) (Table 3). PLD was assayed under the optimal conditions for N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamines (NAPE)–hydrolyzing PLD,29 but a radiolabeled phosphatidylethanolamine was used instead of radiolabeled NAPEs, which are not commercially available. This seems noteworthy, because NAPE-hydrolyzing PLD is considered the checkpoint in AEA synthesis, though the lack of specific inhibitors of its activity makes it difficult to assess conclusively its contribution to AEA metabolism.10 The effect of E2 on FAAH, NOS, 15-LOX, or PLD activities was fully prevented by 100 nM TMX, whereas 100 nM ICI182780, 2 μM SR141716, 2 μM CBD, or 2 μM CAPS was ineffective (Table 3). On the other hand, NOS activity was further enhanced by 100 nM HU-210 up to 160% of the E2-treated cells (Table3). l-NAME, ATFMK, and ETYA almost completely inhibited the activity of the target enzymes in HUVECs, whereas suramin and ST638 reduced cellular PLD to approximately 55% of controls (Table 3). The inhibition of 15-LOX by 10 μM ETYA relieved almost completely the inhibition of FAAH by 100 nM E2 (Table 3), suggesting that 15-LOX activity was involved in this inhibition. EGTA-am reduced the activity of NOS, 15-LOX, and PLD to 42%, 47%, and 49% of the same activities in E2-treated cells, but not that of FAAH (Table 3), probably because NOS,27 15-LOX,30 and PLD39 depend on calcium for their activity, as does NAPE-hydrolyzing PLD in blood cells.40

Coculture with E2-treated HUVECs inhibits serotonin release from human platelets

In pilot experiments it was found that human platelets do not release detectable amounts of [3H]5-HT when cultured for 10 minutes in serum-free EGM-2 Bulletkit medium. However, they release 300 ± 30 fmol/109 cells on stimulation for 2 minutes with 1 μM ADP, a physiological platelet agonist, in keeping with previous reports.41,42 Endothelial cells, pretreated for 4 hours with 100 nM E2, reduced to 50% the release of [3H]5-HT from ADP-stimulated human platelets, whereas control HUVECs had no effect (Figure 4A). Instead, HUVECs pretreated with E2 but in the presence of 100 nM TMX or of 100 U/mL FAAH had no effect on the release of [3H]5-HT from ADP-stimulated platelets, nor did 100 nM E2 or E2-BSA added directly to the medium during the 10-minute coculture period (Figure4A). A dose-dependent decrease of [3H]5-HT release, reaching statistical significance (P < .05) at 50 nM AEA and a minimum (50%) at 100 nM, was observed on treatment of ADP-stimulated platelets for 10 minutes with AEA (Figure 4B). This effect of AEA was not affected by SR141716, SR144528, CBD, or CAPS, each used at 2 μM (Figure 4B). On the other hand, the AEA hydrolysis products arachidonic acid and ethanolamine were ineffective at 100 nM. Platelet membranes were able to bind 500 pM [3H]ADP in rapid filtration assays, and AEA displaced 35% of bound [3H]ADP when used at 100 nM (P < .05 compared with controls), whereas the 5-HT transporter of human platelets43 was not affected by AEA at concentrations up to 10 μM (unpublished results).

Modulation of platelet activity by E2-treated HUVECs, E2, or AEA.

(A) Effect of 10-minute coincubation with HUVECs (1 × 106 cells/test) on the release of [3H]5-HT from human platelets (5 × 109cells/test). Endothelial cells were pretreated with 100 nM E2, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or of 100 U/mL FAAH. Platelets were also incubated directly with 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA. (B) Effect of various concentrations of AEA on [3H]5-HT release from human platelets, also in the presence of SR141716, SR144528, CBD, or CAPS, each used at 2 μM. The effect of 100 nM arachidonic acid (AA) or ethanolamine (Et-NH2) was also investigated. (A-B) 100% = 300 ± 30 fmol/109 platelets. (C) Effect of coincubation with HUVECs, untreated or treated with 100 nM E2, or of incubation with 100 nM E2, 100 nM E2-BSA, 100 nM E2 + 100 nM TMX, or 100 nM E2 + 100 nM ICI182780, on the levels of IP3 and cAMP in human platelets (100% = 8.3 ± 1.0 or 1.2 ± 0.1 pmol × mg protein−1 for IP3 or cAMP, respectively). Values are reported as means ± SD. *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).

Modulation of platelet activity by E2-treated HUVECs, E2, or AEA.

(A) Effect of 10-minute coincubation with HUVECs (1 × 106 cells/test) on the release of [3H]5-HT from human platelets (5 × 109cells/test). Endothelial cells were pretreated with 100 nM E2, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or of 100 U/mL FAAH. Platelets were also incubated directly with 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA. (B) Effect of various concentrations of AEA on [3H]5-HT release from human platelets, also in the presence of SR141716, SR144528, CBD, or CAPS, each used at 2 μM. The effect of 100 nM arachidonic acid (AA) or ethanolamine (Et-NH2) was also investigated. (A-B) 100% = 300 ± 30 fmol/109 platelets. (C) Effect of coincubation with HUVECs, untreated or treated with 100 nM E2, or of incubation with 100 nM E2, 100 nM E2-BSA, 100 nM E2 + 100 nM TMX, or 100 nM E2 + 100 nM ICI182780, on the levels of IP3 and cAMP in human platelets (100% = 8.3 ± 1.0 or 1.2 ± 0.1 pmol × mg protein−1 for IP3 or cAMP, respectively). Values are reported as means ± SD. *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).

Treatment of platelets with 1 μM ADP decreased intracellular cAMP levels from 2.4 ± 0.2 to 1.2 ± 0.1 pmol × mg protein−1, whereas it enhanced IP3 levels from 2.3 ± 0.2 to 8.3 ± 0.9 pmol × mg protein−1, in line with previous observations.14,44 HUVECs never affected the level of either cAMP or IP3 in ADP-stimulated platelets. Instead 100 nM E2, but not E2-BSA, added directly to the medium during the coculture period significantly (P < .05) reduced IP3 (down to 60%) and enhanced cAMP (up to 160%) levels in ADP-treated platelets (Figure4C). This effect was abolished in the presence of either 100 nM TMX or 100 nM ICI182780 (Figure 4C). Finally, AEA did not affect IP3 or cAMP levels in untreated or ADP-treated human platelets at concentrations up to 100 μM (not shown), in keeping with a previous report that AEA does not activate platelets at micromolar concentrations.13

Discussion

In this study we have shown that E2 activates endothelial AMT through calcium and NO-dependent mechanisms. These effects are mediated by the binding of E2 to a surface receptor that has a different affinity for E2 but the same molecular mass as the nuclear ERβ. We have also shown that AMT acts in reverse—that is, it releases rather than takes up AEA so this compound can exert its known cardiovascular actions. Besides the effects of AEA in blood, here we show that it inhibits serotonin release, a general marker of platelet activation and secretion.41-43

The activation of AMT was observed at physiological concentrations of E2,5,6,31 was rapid (30 minutes), and was mediated by a specific E2 surface receptor (ESR), as demonstrated by its inhibition by TMX, by its insensitivity to ICI182780, and by the lack of effect of epi-E2 or cortisol. Consistent with this hypothesis, E2-BSA, which is too large to penetrate the cell membrane, also activated AMT. The structural nature of ESR remains a complicated issue; however, we speculate that it might be similar to nuclear ERβ and might derive from the same transcript, which has already been demonstrated in HUVECs.5 Posttranslational modifications, which must occur to ensure protein targeting to the membrane, may explain the different affinity for E2 and the ICI182780 insensitivity of ESR compared with the nuclear ERβ.5,6,31 E2-induced activation of AMT was fully prevented by l-NAME, indicating that NOS activity was required to couple ESR to AMT. EGTA-am fully inhibited the effect of E2 on AMT, suggesting that calcium ions were required for ESR-AMT coupling. In keeping with these data, E2 caused ESR-mediated increases of NO release (apparent within 15 minutes) and of intracellular calcium (within 5 minutes) in HUVECs at the same physiological concentrations that activated AMT (Figure 1B-C). These rapid effects of E2 are incompatible with the transcriptional activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS) through intracellular E2 receptors, which is known to be a slow (8-hour) and ICI182780-sensitive process.5,6 The results speak in favor of a nongenomic activation of the enzyme,45 which is a typical ESR-mediated effect of E2.5,6,31 HUVECs have an active CB1 receptor7,32 and its activation by HU-210 synergistically potentiates the effect of E2 on AMT and NO release (Figure 2B-C). This is consistent with our previous observation that the activation of CB1 stimulates NO release and, hence, AMT in HUVECs.7 On the other hand, the lack of effect of CBD, CAPS, abnormal-CBD, and capsaicin (Figure 2B-C and data not shown) seems to rule out any involvement of endothelial-type34 or vanilloid11 receptors in the activity of E2.

A major finding of this investigation is that AMT can transport AEA across the membrane in both directions, as shown by uptake and release experiments (Figure 3; Table 2) and as supported by thetrans effect test. Kinetic analysis of AEA uptake and release and the effect of the AMT inhibitor AM404 strongly suggest that the in-and-out movement of AEA occurred through the same transporter. E2 enhanced AEA release in the same TMX-, HU-210–,l-NAME–, and EGTA-am–sensitive and the same ICI182780-, SR141716-, CBD-, and CAPS-insensitive manner (Table 2) observed with AEA uptake (Figure 2B). Because E2, again in a TMX-sensitive and an ICI182780-insensitive manner, reduced the activity of the AEA-hydrolyzing enzyme FAAH and increased the activity of the AMT-stimulating enzyme NOS and of the AEA-synthesizing enzyme PLD (Table 3), it is reasonable to conclude that the biologic action of E2 is to enhance the release rather than the uptake of this lipid. This unprecedented observation of a physiological stimulus for AMT to act in reverse explains the reports of a retrograde signaling mediated by endocannabinoids in the brain, based on a calcium-dependent release of AEA from postsynaptic neurons (for a review, see MacDonald and Vaughan46 and the references cited therein). A further point of interest is that E2 stimulates 15-LOX in HUVECs, whereas the inhibition of this enzyme by ETYA reverses the effects of E2 on FAAH (Table 3). Thus it appears that lipoxygenase activity is responsible for the inhibition of FAAH induced by E2. An E2-mediated release of AEA from HUVECs might lead to activation of CB1 receptors by AEA itself, followed by NOS activation (Table 3) and further AEA release (Table 2), by an autocrine mechanism. The effect of the synthetic CB1 agonist HU-210 strongly supports this hypothesis.

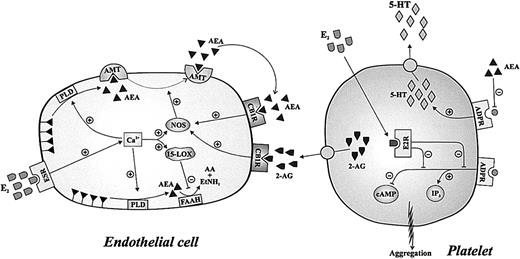

Once released within the blood vessels, AEA can exert its manifold actions on the cardiovascular system, spanning from vasodilation and related hypotension and bradycardia (for a review, see Kunos et al12) to modulation of cell migration16 and of immune response.18 Interestingly, E2 also regulates the immune system.47 Another effect of E2 is on platelets,1 which play a critical role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease3 and express an intracellular E2 receptor.4 Platelets share several features with neurons and respond to endocannabinoids,13,14 thus representing a useful model for the less accessible central nervous system. It is known that endocannabinoids can modulate serotonergic transmission.48For instance, AEA has recently been shown to decrease 5-HT levels in the hippocampus.49 Here it is shown for the first time that the secretion of 5-HT from ADP-stimulated platelets is reduced by a diffusible factor released by E2-stimulated HUVECs in a TMX-sensitive manner, but not by E2 itself (Figure 4A). The effect of this factor is abolished by FAAH (Figure 4A) and is reproduced by AEA added at nanomolar concentrations (Figure 4B), similar to those found in blood.50 These findings suggest that AEA released from HUVECs on stimulation with E2 inhibits 5-HT secretion from stimulated platelets. This effect of AEA does not involve classical (CB1 or CB2) or nonclassical (endothelial-type) cannabinoid receptors or vanilloid receptors in platelets; rather, it occurs through a partial antagonism by AEA at ADP receptors (Figure 4B and data not shown). Because AEA does not affect IP3 levels or those of cAMP in platelets, it can be speculated that AEA might interfere with the binding of ADP to the P2X receptor, which is independent of IP3 or cAMP, at variance with the P2TAC or P2TPLCreceptors.44 However, because ADP binding to platelets is complex, the interactions of endocannabinoids with ADP signaling deserve further investigation. In our study it appeared that whatever the signal transduction pathway(s), AEA reduced 5-HT secretion from platelets, whereas E2 did not. On the other hand, E2 decreased IP3 and increased cAMP levels in ADP-treated platelets, which is consistent with reduced platelet activation,44whereas micromolar concentrations of AEA did not (Figure 4C and data not shown). Because E2 acts on platelets in a TMX- and ICI182780-sensitive manner, whereas E2-BSA is ineffective (Figure 4C), it can be suggested that it binds at an intracellular receptor.1,4 Moreover, the results suggest that AEA released from endothelial cells on E2 stimulation might complement the biologic activity of E2 itself because it can directly inhibit platelet aggregation and indirectly inhibit the release of 5-HT. The cross-talk between endothelial cells and platelets can be even more complex—platelets release primarily 2-AG,12,14 which is the main physiological agonist of CB1 receptors and is not taken up by HUVECs.7 Thus, it is tempting to speculate that platelet-derived 2-AG binds at CB1 receptors in endothelial cells, thus stimulating the release of AEA, which in turn inhibits ADP binding to platelets and 5-HT release (Figure 5).

Regulation of endothelial AMT by E2 and cross-talk with platelets.

Binding of E2 to an endothelial ESR triggers elevation of intracellular calcium, which leads to increased activity of PLD, 15-LOX, and NOS. Activation of PLD enhances the release of AEA from membrane phospholipid precursors, whereas activation of NOS stimulates AMT and activation of 15-LOX inhibits AEA hydrolysis by FAAH. Taken together, E2 stimulates the release of AEA from endothelial cells. Binding of AEA itself, or of 2-AG released from platelets, to type 1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1R) of endothelial cells further potentiates AEA release. E2 also binds to an intracellular receptor (E2R) in platelets, thus preventing IP3 elevation and cAMP reduction induced by binding of ADP to its receptors (ADPRs). On the other hand, AEA inhibits ADP-induced release of 5-HT from platelets.

Regulation of endothelial AMT by E2 and cross-talk with platelets.

Binding of E2 to an endothelial ESR triggers elevation of intracellular calcium, which leads to increased activity of PLD, 15-LOX, and NOS. Activation of PLD enhances the release of AEA from membrane phospholipid precursors, whereas activation of NOS stimulates AMT and activation of 15-LOX inhibits AEA hydrolysis by FAAH. Taken together, E2 stimulates the release of AEA from endothelial cells. Binding of AEA itself, or of 2-AG released from platelets, to type 1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1R) of endothelial cells further potentiates AEA release. E2 also binds to an intracellular receptor (E2R) in platelets, thus preventing IP3 elevation and cAMP reduction induced by binding of ADP to its receptors (ADPRs). On the other hand, AEA inhibits ADP-induced release of 5-HT from platelets.

In conclusion, the results reported here demonstrate that E2 activates the synthesis and inhibits the degradation of AEA in human endothelial cells by acting at a surface receptor and causing a calcium-dependent release of NO. As a consequence, AEA is released in blood, where it can modulate the cardiovascular and immune systems. In particular, AEA released from estrogen-stimulated endothelial cells is capable of reducing the secretion of 5-HT from platelets. This newly found interplay between estrogen and AEA metabolism suggests that endocannabinoids might mediate some of the beneficial effects of estrogen, and it seems to indicate a novel approach for the management of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women.

We thank Prof Francesco Malatesta (University of L'Aquila, Italy) for fitting the time-course data of the in-and-out movement of anandamide and Dr Marianna Di Rienzo for skillful assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 1, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1444.

Supported by Istituto Superiore di Sanità (III AIDS Program) and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (Biotechnology Program L. 95/95), Rome, Italy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mauro Maccarrone, Department of Experimental Medicine and Biochemical Sciences, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Via Montpellier 1, I-00133 Rome, Italy; email:maccarrone@med.uniroma2.it.

![Fig. 2. Binding of E2 to HUVECs and modulation of the effects of E2 by various compounds. / (A) Saturation curves of the binding of [3H]E2 to cell membranes, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or 100 nM ICI182780. Vertical bars represent SD values. (Inset) Western blot analysis of nuclear (N) and membrane (M) homogenates (10 and 20 μg/lane, respectively), reacted with anti-ERβ antibodies. Molecular mass markers are shown on the right side. (B) Effect of TMX, ICI182780, or HU-210 (100 nM each), of SR141716, CBD, or CAPS (2 μM each), ofl-NAME (400 μM) or of EGTA-am (50 μM) on the activation of AMT by 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA (100% = 25 ± 3 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1). (C) Effect of the same treatments discussed in panel B on the release of NO and the intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) of HUVECs. Values are reported as means ± SD. In all panels, *P < .01 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1444/5/m_h82323461002.jpeg?Expires=1765956906&Signature=AO7ObwxfboaxBW0sXzHntrVw7uglYaoe7SyZNj0U5z1QpqPPxj7iXaTNmSmb1gpz4omwyQ~gU9wlruU6kuWreGSdcBYerdtwMhNLXQMNSu3cQrKo8TakaSRGkezldyjcjCFlDV3xvueKrJXKwISGD6mhGV4C~B-g02lB1ChlVsgOOxxABQhMEm7~80IUtlywxBhEIN5AYByGUFYmMp8jeKx~maNUw-56oi4UJWY6wJq~hifK9V8NxeMy9kQYisXnbrgG2gfdHHlaCtytSd~JxLpS6FxjsM9rw38t2WEEyQ1xHs9HPKB14G7hgOm9AxHTU06XTNwLIrsA91JPaELetw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 3. Transport of AEA across HUVEC membranes. / (A) Time-course of the uptake of [3H]AEA from the extracellular space (movement in) or of the release of [3H]AEA from endothelial cells preloaded with [3H]AEA (movement out), in the presence of 10 μM ATFMK (100% = 420 ± 40 or 320 ± 30 fmol/106 cells, for the in-and-out transport, respectively). # designates the effect of 10 μM AM404 on the release of [3H]AEA at 20 minutes. (B) Dependence of the release of [3H]AEA on the concentration of E2, E2-BSA, epi-E2, or cortisol. (C) Representative chromatogram of the lipids extracted from the culture media of HUVECs, untreated (control), or treated with 100 nM E2 for 4 hours. The peaks coeluted with authentic AEA and their areas were within the linearity range of calibration curves (inset). Values are reported as means ± SD. In panel B, *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control (P > .05 in all other cases).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1444/5/m_h82323461003.jpeg?Expires=1765956906&Signature=Wom4m8wNRMOq1Db5gEXfI-JJ3b8tHDyxYm~LPonryT6Q8ZdiR8dKse4Z~5mUCy3wBlLHfvXzSL8JpSgnww050Vdw8x4VnYskfmQ5WwKEhDM3SwAcU67SntjWxrcvQToPLE7dZr8~zIfxvhfXoCJiW7e-~iCJnTAMzsd9UznjxZYwKO0XzicWQKS1L1peuZqddeiStRviIC9rWtzOWF~d8clE6ydfSPOPZ5zO~oVxyyCSPjAl-co55dRJgFTxPW-O08RXjRUmogrNQXkKXpAVd6zWy5dWooB5stZaUxzs5CV1cAai1OA8ZQxpCuExA1ivFJ9jvIMMGfJ0Gekawks0Zw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Modulation of platelet activity by E2-treated HUVECs, E2, or AEA. / (A) Effect of 10-minute coincubation with HUVECs (1 × 106 cells/test) on the release of [3H]5-HT from human platelets (5 × 109cells/test). Endothelial cells were pretreated with 100 nM E2, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or of 100 U/mL FAAH. Platelets were also incubated directly with 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA. (B) Effect of various concentrations of AEA on [3H]5-HT release from human platelets, also in the presence of SR141716, SR144528, CBD, or CAPS, each used at 2 μM. The effect of 100 nM arachidonic acid (AA) or ethanolamine (Et-NH2) was also investigated. (A-B) 100% = 300 ± 30 fmol/109 platelets. (C) Effect of coincubation with HUVECs, untreated or treated with 100 nM E2, or of incubation with 100 nM E2, 100 nM E2-BSA, 100 nM E2 + 100 nM TMX, or 100 nM E2 + 100 nM ICI182780, on the levels of IP3 and cAMP in human platelets (100% = 8.3 ± 1.0 or 1.2 ± 0.1 pmol × mg protein−1 for IP3 or cAMP, respectively). Values are reported as means ± SD. *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1444/5/m_h82323461004.jpeg?Expires=1765956906&Signature=1uXR3sVN2WUWnE~k7J5eUzX~IytAMGcFuQlTd5xW69ZXfTAxYwDNPtY3v583kQcR3ClqCWqlYT8GnHAZqVr32A371ouA6IqBmAdnEPXe~gl6h5iXq7jsCMFvRto7JNmB5nIAbbLkxD8Ym1saCtqjcwXCuuomFfi1V4Rmqsmh5PQRVgWF9~cWGHVyXjHAaAnG7neVF6KyeYg-IXA~y-LckasfJR4gS-ZY1~gOkbBKTKSZxAcL3KklnRgM~DU-3xgSCca7qdEbucuV~gKoio7ChowXJYXU0xl8h58F-IVs1yBhE~0L~rCs6Baw3HHix58QWHRhmk1moHq~1BYoOzLV6Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. Binding of E2 to HUVECs and modulation of the effects of E2 by various compounds. / (A) Saturation curves of the binding of [3H]E2 to cell membranes, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or 100 nM ICI182780. Vertical bars represent SD values. (Inset) Western blot analysis of nuclear (N) and membrane (M) homogenates (10 and 20 μg/lane, respectively), reacted with anti-ERβ antibodies. Molecular mass markers are shown on the right side. (B) Effect of TMX, ICI182780, or HU-210 (100 nM each), of SR141716, CBD, or CAPS (2 μM each), ofl-NAME (400 μM) or of EGTA-am (50 μM) on the activation of AMT by 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA (100% = 25 ± 3 pmol × minute−1 × mg protein−1). (C) Effect of the same treatments discussed in panel B on the release of NO and the intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) of HUVECs. Values are reported as means ± SD. In all panels, *P < .01 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1444/5/m_h82323461002.jpeg?Expires=1766650227&Signature=vY7~mBLzX4LJOkak~PCSYdMPNdYLQRyXTQUoOVaTwmkbUTC3g36kZcKQXeEe79AxKTQLxF2Iz0wGduTAzwX2aHxEdY10J-ecJ77Mm-MIXuTRmuUfCeYR83Oa46iV-s5Yd7kpJoijzviHkuCqFVKquUOJ-pGFS2kgvzF-gu3G-eHMglyoR~-fxqapi85VFRjE0nEwadk3x5~qCPKsDozgAn~1c47Dm5oVPY7ikhj0xaHhV5SLNwKwsllXJymU28I~QmxPxB2NQzzqRS-hKoF~0miV9AjbAeMhKhvz04yIjloao-gApsbA4Bh~rgvGGih07TieXJu~bLWwlPtys4OsYw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 3. Transport of AEA across HUVEC membranes. / (A) Time-course of the uptake of [3H]AEA from the extracellular space (movement in) or of the release of [3H]AEA from endothelial cells preloaded with [3H]AEA (movement out), in the presence of 10 μM ATFMK (100% = 420 ± 40 or 320 ± 30 fmol/106 cells, for the in-and-out transport, respectively). # designates the effect of 10 μM AM404 on the release of [3H]AEA at 20 minutes. (B) Dependence of the release of [3H]AEA on the concentration of E2, E2-BSA, epi-E2, or cortisol. (C) Representative chromatogram of the lipids extracted from the culture media of HUVECs, untreated (control), or treated with 100 nM E2 for 4 hours. The peaks coeluted with authentic AEA and their areas were within the linearity range of calibration curves (inset). Values are reported as means ± SD. In panel B, *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control (P > .05 in all other cases).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1444/5/m_h82323461003.jpeg?Expires=1766650227&Signature=n4X9y5nY8XlnG8J80xHPwDWlys8pQBJwUiIxsT2BmF5Fno~OqGT6X8aNSs4KbyqTIoArz1abdWeGlHV4XU4BH~ZtNokhjVZI9IpmbN9Wu2rJueoEEtnXne-BhWaoQxzVWu7s-VFN2Px5Tcetu38mlh9qoT2UkyhDsGJf6rnT-bU6EBBPeZo6djWXU5V-l8aTx-scd~pFesBeUGslwRxcrlGSWFuvVTNd7jVrEd65jnA8fwWxJrDOpJtvRxPfmxoHw7pE8mOZgp5sEMH7lip9YU03ydDRz0m~KICF2NXKMXEmrrzfU1ZBFhSYhgzzmjz60IJNkCWup8Blprp~SxcMIw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Modulation of platelet activity by E2-treated HUVECs, E2, or AEA. / (A) Effect of 10-minute coincubation with HUVECs (1 × 106 cells/test) on the release of [3H]5-HT from human platelets (5 × 109cells/test). Endothelial cells were pretreated with 100 nM E2, alone or in the presence of 100 nM TMX or of 100 U/mL FAAH. Platelets were also incubated directly with 100 nM E2 or 100 nM E2-BSA. (B) Effect of various concentrations of AEA on [3H]5-HT release from human platelets, also in the presence of SR141716, SR144528, CBD, or CAPS, each used at 2 μM. The effect of 100 nM arachidonic acid (AA) or ethanolamine (Et-NH2) was also investigated. (A-B) 100% = 300 ± 30 fmol/109 platelets. (C) Effect of coincubation with HUVECs, untreated or treated with 100 nM E2, or of incubation with 100 nM E2, 100 nM E2-BSA, 100 nM E2 + 100 nM TMX, or 100 nM E2 + 100 nM ICI182780, on the levels of IP3 and cAMP in human platelets (100% = 8.3 ± 1.0 or 1.2 ± 0.1 pmol × mg protein−1 for IP3 or cAMP, respectively). Values are reported as means ± SD. *P < .01 and **P < .05 compared with untreated control; #P < .01 and @P < .05 compared with E2-treated cells (P > .05 in all other cases).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-05-1444/5/m_h82323461004.jpeg?Expires=1766650227&Signature=rQ600n3rQ7Nw8THkRBmc0vLTOgZT~mLS9y4oakfkTfvX8zk09qm~dvzmptrh5I6r5Mb~rabfpFAEwhTYyGjx09SjJ3stQGyPCWqGzL5dYOdgmw3YOGAfUnbzmEF4JjvA-EckJuyQm8N-aiBnvsfo-XCPnNocVwL004NUb6LFzuJ~7ye-8k-XlWidOFxuKx9f9~CC3oGTvKmwxcVLnV3PXhoR8WEzF8xr2cSE0kO6LyOU-kHUNd-bAB7JQr5R3tR01gg-sYQNWjMgsOCQJlVjfpLqn75gHTpqxsWAFElkmRCJHoFAV3XGpuvDUAv4jq1s3lXZK-TjDdFqAWLhXsqi4w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)