The binding of von Willebrand factor (VWF) to glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX-V stimulates transmembrane signaling events that lead to platelet adhesion and aggregation. Recent studies have implied that activation of Src family kinases is involved in GPIb-mediated platelet activation, although the related signal transduction pathway remains poorly defined. This study presents evidence for an important role of Src and GPIb association. In platelet lysates containing Complete, a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor mixture, Src and Lyn dynamically associated with GPIb on VWF-botrocetin stimulation. Cytochalasin D, which inhibits translocation of Src kinases to the cytoskeleton, further increased Src and GPIb association. Similar results were obtained with botrocetin and monomeric A1 domain, instead of intact VWF, with induction of both Src activation and association between GPIb and Src. These findings suggest that ligand binding of GPIb, without receptor clustering, is sufficient to activate Src. Immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that Src, phosphoinositide 3– kinase (PI 3–kinase), and GPIb form a complex in GPIb-stimulated platelets. When the p85 subunit of PI 3–kinase was immunodepleted, association of Src with GPIb was abrogated. However, wortmannin, a specific PI 3–kinase inhibitor, failed to block complex formation between Src and GPIb. The Src-SH3 domain as a glutathione S-transferase (GST)–fusion protein coprecipitated the p85 subunit of PI 3–kinase and GPIb. These findings taken together suggest that the p85 subunit of PI 3–kinase mediates GPIb-related activation signals and activates Src independently of the enzymatic activity of PI 3– kinase.

Introduction

Platelet adhesion to subendothelial structures is an early and critical event in hemostasis and thrombosis. von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a major adhesive glycoprotein (GP) required for normal hemostasis under conditions of high shear stress, such as those that occur in small arterioles and arterial capillaries.1 In the presence of high shear stress or modulators such as botrocetin or ristocetin, VWF binds to the platelet membrane GPIb-IX-V complex and initiates intracellular signals leading to platelet activation.2 These include protein tyrosine phosphorylation, activation of protein kinase C, activation of phosphoinositide 3–kinase (PI 3–kinase), elevation of the intracellular calcium ion concentration, and synthesis of thromboxane A2.3-8 These intracellular signaling events play an essential role in the reorganization of platelet cytoskeletal actin filaments leading to platelet adhesion and spreading, and activation of integrin αIIbβ3, with resultant platelet aggregation.9-11

Recently, the events related to protein-tyrosine phosphorylation have emerged as important signals mediated by GPIb.3-6,12-14GPIb-mediated platelet activation in response to VWF plus botrocetin, shear stress, or VWF from patients with von Willebrand disease type IIb, induces tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins, suggesting that VWF binding to GPIb causes the activation of tyrosine kinases such as Syk and Src.5 Coassociated transmembrane proteins, FcRγ chain and FcγRIIA, containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) have been shown to be involved in GPIb-mediated platelet activation processes. For example, the tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk, linker for activation of T cells (LAT), and phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2) are dependent on the FcRγ chain.6,12 13 Because these ITAM-containing proteins lie downstream of activation of Src family kinases, it is important to investigate how GPIb stimulation mediates Src kinase activation. However, to date, it has remained elusive how the GPIb-VWF interaction is coupled to activation of Src kinases.

The GPIb-IX-V complex is composed of 4 different polypeptides, GPIbα, GPIbβ, GPIX, and GPV, in a ratio of 2:2:2:1.2 This complex is neither associated with GTP-binding proteins nor does it possess intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity. It also contains no tyrosine residues capable of phosphorylation. Recent studies have identified several signaling molecules associated with the cytoplasmic domain of GPIb-IX-V that could play a critical role in signal transduction. One of these molecules is PI 3–kinase.7,15The interaction of PI 3–kinase with the GPIb-IX-V complex is mediated through their association with 14-3-3ζ. PI 3–kinase plays multiple functional roles in mammalian cells. Most of its effects depend on its activation with resultant production of D-3 lipids, which target signaling proteins such as Btk and PLCγ to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane.16-18 On the other hand, there is increasing evidence indicating that the regulatory subunit of PI 3–kinase, p85, can act as an assemblage molecule, binding a diverse number of intracellular signaling proteins, especially Src family kinases,19-24 and thus regulating various cellular functions independently of the catalytic activity of PI 3–kinase.25 26 In this study, we sought to determine whether PI 3–kinase is involved in the GPIb-related signal transduction pathway.

With a number of receptors, especially those for growth factors and adhesive molecules, clustering of receptors is a prerequisite for signal transduction; simple binding of ligand is insufficient. It is widely accepted that VWF, with its multimeric binding sites, induces clustering of GPIb molecules on the platelet membrane, thereby eliciting downstream signals. In accord with this notion, neither dispase-treated VWF nor the monomeric A1 domain of VWF can induce platelet aggregation.27,28 There are, however, several reports suggesting that simple ligand binding of GPIb can partially elicit some activation events.29 30 In this report, we therefore also sought to address this issue by using recombinant A1 domain of VWF and cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following materials were obtained from the indicated suppliers: monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) against Lyn and Syk (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan); anti-phosphotyrosine MoAb, PY20 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); anti-phosphotyrosine MoAb, 4G10, anti-Src MoAb, anti-FcRγ chain, anti-Lck, and anti-PI 3–kinase p85 polyclonal antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY); anti-Fyn MoAb, polyclonal anti-PLCγ2, anti-PI 3–kinase p85, and peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); calpeptin (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA); glutathione-Sepharose 4B and protein A-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham, United Kingdom); peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG antibody (Cappel, Durham, NC); bovine serum albumin (BSA), Tween-80, prostaglandin I2, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), Na3VO4, Triton X-100, enolase, cytochalasin D, latrunculin A, wortmannin, and LY294002 (Sigma, St Louis, MO); and Complete (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

VWF and botrocetin were purified as described previously.5,31 The recombinant A1 domain of VWF linked to maltose-binding proteins was generously donated by the Ajinomoto Company (Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan).32 The noninhibitory anti-GPIb MoAb, WGA3, was provided by Dr M. Handa (Keio University, Tokyo, Japan). Glutathione S-transferase (GST)–fusion proteins containing the tandem SH2 domains of Syk or the SH3 domain of Src were obtained from Dr C.-L. Law (University of Washington, Seattle) and Dr Ashley Dunn (Ludwig Institute, Melbourne, Australia), respectively. Jararaca GPIb-binding protein was donated by Dr Y. Fujimura (Nara Medical University, Nara, Japan).

Preparation and stimulation of platelets

Human venous blood was obtained from healthy, drug-free volunteers on the day of the experiment, using acid-citrate-dextrose (120 mM sodium citrate, 110 mM glucose, 80 mM citric acid) as anticoagulant. Washed platelets were prepared as previously described,12 and suspended in modified HEPES-Tyrode buffer (134 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 2.9 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 20 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 5 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.3). Unless otherwise stated, washed platelet suspensions were adjusted to 0.8 × 109cells/mL and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C before experiments.

Immunoprecipitation and GST-fusion protein precipitation

After the indicated time intervals of activation, platelets were solubilized with an equal volume of 2 × ice-cold lysis buffer (100 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]/HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM EGTA [ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid], 2 mM PMSF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 100 μg/mL leupeptin, 2% Triton X-100, and 1 tablet of Complete in 25 mL lysis buffer) and kept on ice for 30 minutes. The lysis buffer used in this study contained Complete, a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor mixture, unless otherwise stated. All subsequent steps were performed at 4°C. The lysates were centrifuged at 15 000g for 5 minutes, and the resulting supernatants were precleared by incubation for 30 minutes with protein A-Sepharose for immunoprecipitation experiments, or with glutathione-Sepharose for GST-fusion protein precipitation. For immunoprecipitation, the supernatants were then incubated with the appropriate antibodies, followed by the addition of protein A-Sepharose. For GST-fusion protein precipitation, the supernatants were incubated with the indicated fusion proteins, followed by the addition of glutathione-Sepharose beads. The precipitates obtained after centrifugation were washed 3 times with 1 × lysis buffer before the addition of Laemmli sample buffer.

Immunoblotting

Precipitated proteins from equal number of platelets were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 10% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After extensive washing with PBS containing 0.4% Tween-80, the immunoblots were incubated with the appropriate antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature, or overnight at 4°C. Antibody binding was detected using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted at 1:7500, and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent. For reprobing with other antibodies, the antibody bound to PVDF membranes was removed with a stripping buffer (2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol) at 50°C for 20 minutes. After washing, the membranes were blocked with 1% BSA and reprobed with the indicated antibodies. Where indicated, the level of proteins detected by immunoblotting was quantitatively analyzed using a PDI420oe scanner (PDI, New York, NY) with Quantity One 2.5a software for Macintosh (PDI).

Immunoprecipitation kinase assay

The immunoprecipitates were washed 3 times with 1 × lysis buffer, and once with HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES/NaOH, 1 mM Na3VO4, pH 8.0), followed by further processing for an in vitro kinase assay, according to the method described previously.5 Briefly, the beads were incubated with 50 μL kinase reaction buffer (100 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 8.0, 5 mM MnCl2, 50 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM Na3VO4) containing 10 μg acid-treated enolase. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 2.0 μM γ-32P] adenosine triphosphate (ATP; 10 μCi [0.37 MBq]). After 10 minutes of incubation at 20°C, reactions were stopped by the addition of Laemmli buffer and then subjected to boiling for 3 minutes. After Western blotting, the membrane was treated with 1 M KOH for 60 minutes and then dried. The radioactivity was quantified with a BAS-2000 phosphorimage analyzer (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Subcellular fractionation of platelets

After the indicated time of activation, platelets were lysed with an equal volume of 2 × ice-cold lysis buffer containing Complete and kept on ice for 30 minutes. All subsequent steps were performed at 4°C. The lysates were centrifuged at 15 000g for 5 minutes, and the resulting supernatant (the Triton-soluble fraction) was discarded. After washing, the pellet (the Triton-insoluble fraction) was solubilized in 1 × SDS sample buffer. Alternatively, the pellet was solubilized in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 158 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EGTA, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and Complete) for 60 minutes at 4°C. This lysate was centrifuged at 15 000g for 5 minutes. The supernatant (the Triton-insoluble/RIPA-soluble fraction) was collected, and subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis as described in the previous paragraph.

Presentation of data

Unless stated otherwise, the results shown are from a single experiment representative of at least 3 separate experiments. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of these experiments.

Results

Stimulation-dependent association of Src and Lyn with GPIb in platelets

Previous studies have shown that Src and Lyn are specifically involved in GPIb signaling. They have been shown to form a complex with the FcRγ chain or Syk, as well as to translocate to the cytoskeleton.5,12 Although we previously reported that a tyrosine kinase activity associates with GPIb on VWF-GPIb interaction, the identity of this tyrosine kinase was not determined.5The failure to identify tyrosine kinases by Western blotting was attributed to the insensitivity of this method relative to the in vitro kinase assay. Alternatively, it is possible that tyrosine kinases were dissociated from GPIb by proteases during the process of cell lysis and immunoprecipitation. Calpain activation occurs in GPIb-mediated platelet activation, resulting in the cleavage of multiple signaling molecules such as Src, PTP1B, FAK, and talin, as well as GPIb itself.33 To see whether activated calpain affects the association of tyrosine kinases with GPIb, especially Src family kinases, we added 50 μg/mL calpeptin, a specific calpain inhibitor, to the lysis buffer in addition to the protease inhibitors, PMSF and leupeptin, used in our previous study. There was, however, little increase in the amount of Src coimmunoprecipitated with GPIb (lanes 1-3 versus 4-6 in Figure 1A). Recently, however, there has been increasing evidence that proteases other than calpain, such as matrix metalloproteinases and caspases, are also present in platelets and can modulate platelet function.34-39 We therefore added Complete, a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor mixture able to inhibit a wide range of proteases, to the lysis buffer. As shown in Figure 1A (lanes 7-9), a significant amount of Src was recovered in GPIb immunoprecipitates of VWF-stimulated platelets in the lysates containing Complete, but not with control platelet lysates (lanes 1-3), suggesting that Src associates with GPIb on GPIb-VWF interaction. These findings suggest that the interaction between Src and GPIb is more sensitive to proteolysis than ordinary protein-protein interactions related to tyrosine phosphorylation. It is likely that the Src-GPIb interaction is not direct, probably mediated by an intermediate signaling molecule. Hereafter, all experiments were performed with lysis buffer containing Complete, unless otherwise stated.

Physical association of Src, Lyn, and tyrosine kinase activity with GPIb on VWF-botrocetin stimulation.

(A) After stimulation with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), platelets were solubilized with lysis buffer (lanes 1-3) as described in “Materials and methods,” or with lysis buffer including 50 μg/mL calpeptin (lanes 4-6), or with lysis buffer including Complete (lanes 7-9). The lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-GPIb MoAb WGA-3. Precipitated proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAb, respectively. (B) Platelets were preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with vehicle solutions (control) or 20 μg/mL jararaca GPIb-BP. After stimulation as described in panel A, the platelets were solubilized with a lysis buffer containing Complete, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GPIb MoAb. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src, anti-Lyn, anti-Fyn, and anti-GPIb MoAbs as indicated at the left of each panel. (C) The precipitates with anti-GPIb MoAb were prepared as described in panel B and analyzed in an in vitro kinase assay using enolase as the exogenous substrate. The proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and quantified with a BAS 2000 phosphorimager. Equivalent precipitation of GPIb was confirmed by immunoblotting and is shown in the lower panel. HC represents the band presumably derived from the IgG heavy chain.

Physical association of Src, Lyn, and tyrosine kinase activity with GPIb on VWF-botrocetin stimulation.

(A) After stimulation with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), platelets were solubilized with lysis buffer (lanes 1-3) as described in “Materials and methods,” or with lysis buffer including 50 μg/mL calpeptin (lanes 4-6), or with lysis buffer including Complete (lanes 7-9). The lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-GPIb MoAb WGA-3. Precipitated proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAb, respectively. (B) Platelets were preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with vehicle solutions (control) or 20 μg/mL jararaca GPIb-BP. After stimulation as described in panel A, the platelets were solubilized with a lysis buffer containing Complete, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GPIb MoAb. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src, anti-Lyn, anti-Fyn, and anti-GPIb MoAbs as indicated at the left of each panel. (C) The precipitates with anti-GPIb MoAb were prepared as described in panel B and analyzed in an in vitro kinase assay using enolase as the exogenous substrate. The proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and quantified with a BAS 2000 phosphorimager. Equivalent precipitation of GPIb was confirmed by immunoblotting and is shown in the lower panel. HC represents the band presumably derived from the IgG heavy chain.

We also found in VWF-stimulated platelets that association of Src with GPIb is a rapid process; it increased as soon as 15 seconds after stimulation and peaked at 1 minute, followed by a decrease at 5 minutes (3.1 ± 0.6 fold [n = 3] increase over the control at a maximum point; Figure 1B). In a pattern similar to Src, Lyn also associated with GPIb, albeit to a lesser degree (Figure 1B). In contrast to these 2 tyrosine kinases, Fyn and other members of the Src kinase family were not detected (Figure 1B; data not shown). When platelets were pretreated with jararaca GPIb-binding protein (GPIb-BP), which competitively inhibits VWF binding to GPIb,40 Src and Lyn association with GPIb were both blocked (Figure 1B), suggesting that the increased level of Src and Lyn association with GPIb is specific for GPIb-mediated platelet activation. Consistent with the increased level of GPIb-associated Src, the inclusion of Complete in the lysis buffer also allowed us to observe in immunoprecipitation kinase assays the pronounced autophosphorylation of a 60-kDa protein associated with GPIb, as well as the included enolase substrate (Figure 1C), implying that Src is the main candidate responsible for GPIb-associated tyrosine kinase activity.

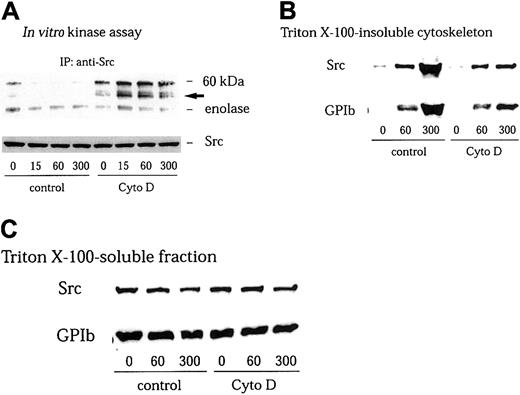

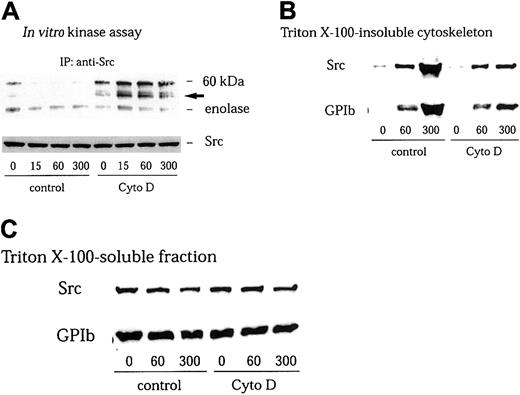

GPIb stimulates redistribution of Src to the cytoskeleton, with resultant loss of its activity in the Triton-soluble fraction

We have found in this study that GPIb stimulates association of Src with GPIb. However, we were not able to detect an increase in Src kinase activity in anti-Src immunoprecipitates in the Triton-soluble fraction5 (Figure 2A). It has been well documented that members of the Src family kinases are redistributed to the cytoskeleton during platelet activation.41-43 Yuan and colleagues and we have found that GPIb stimulation induces translocation of Src as well as Lyn to the cytoskeleton as an early event during platelet activation.5 32 Thus, it is possible that GPIb associated with Src translocates to the reorganized cytoskeleton thereby depleting Src in the Triton-soluble fraction. However, although we attempted to measure Src kinase activity in the RIPA-extracted actin cytoskeletal fraction, an increase in Src activity was not detectable. It is likely that the presence of SDS in the RIPA buffer interfered with the enzyme activity of Src. We therefore sought to recover Src in the Triton-soluble fraction by preventing its translocation with cytochalasin D, which binds to the growing ends of actin filaments and inhibits actin polymerization by blocking the further addition of monomeric actin molecules. As shown in Figure 2B, pretreatment of platelets with 1 μM cytochalasin D indeed reduced cytoskeletal translocation of Src and GPIb mediated by VWF plus botrocetin stimulation to approximately 22% ± 5% (n = 3) and 24% ± 6% (n = 3) of control, respectively. The amounts of GPIb or Src in Triton-soluble fractions were little affected by cytochalasin D treatment (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the inhibition by cytochalasin D of cytoskeletal translocation of Src or GPIb allowed us to observe an increase in autophosphorylation of Src and its kinase activity in the Triton-soluble fraction, as early as 15 seconds after stimulation (Figure 2A).

Cytochalasin D inhibits cytoskeletal translocation of Src and GPIb and increases Src activity in VWF-stimulated platelets.

Platelets were preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.25% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as control or 1 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D), and stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). The platelets were solubilized with lysis buffer containing Complete. (A) The platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Src MoAb, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by an in vitro kinase assay using enolase as the exogenous substrate. The arrow represents the band presumably derived from IgG heavy chain. (B) Triton X–insoluble fractions were harvested by centrifugation at 15 000g for 5 minutes. The pellets were solubilized with Laemmli buffer. Cytoskeletal proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs. (C) Supernatant after removal of the Triton X–insoluble fraction (Triton X-100-soluble fraction) was mixed with Laemmli sample buffer. Fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs.

Cytochalasin D inhibits cytoskeletal translocation of Src and GPIb and increases Src activity in VWF-stimulated platelets.

Platelets were preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.25% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as control or 1 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D), and stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). The platelets were solubilized with lysis buffer containing Complete. (A) The platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Src MoAb, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by an in vitro kinase assay using enolase as the exogenous substrate. The arrow represents the band presumably derived from IgG heavy chain. (B) Triton X–insoluble fractions were harvested by centrifugation at 15 000g for 5 minutes. The pellets were solubilized with Laemmli buffer. Cytoskeletal proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs. (C) Supernatant after removal of the Triton X–insoluble fraction (Triton X-100-soluble fraction) was mixed with Laemmli sample buffer. Fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs.

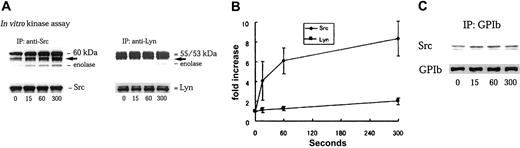

Ligand binding of GPIb is sufficient to activate Src, but its clustering is necessary for downstream signaling

It has been widely held that GPIb clustering with multimeric VWF is a prerequisite for full activation of platelets. Our finding that Src is activated by GPIb stimulation in cytochalasin D–pretreated cells in which receptor clustering would be predicted to be blocked disagress with this notion and suggests that at least part of GPIb-mediated signal transduction does not require GPIb clustering. The recombinant A1 domain of VWF is monomeric.32 Although it can interact with GPIb in the presence of botrocetin, it fails to engage multiple GPIb receptors and to induce aggregation or actin polymerization as well as subsequent cytoskeletal relocation of Src and Lyn.30 When platelets were stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 20 μg/mL A1 domain, Src activation, as detected by its autophosphorylation and enolase phosphorylation, gradually increased in a time-dependent manner (Figure3A). Densitometric analysis of enolase phosphorylation revealed that Src activity was increased 8.3-fold 5 minutes after stimulation (Figure 3B). In contrast, we did not detect a significant change in the kinase activity of Lyn, at least over this time course (Figure 3A-B). A1 domain interaction with GPIb also induced Src association with GPIb (Figure 3C). These results suggest that, without receptor clustering, occupancy of GPIb with the A1 domain of VWF is sufficient to stimulate Src association with GPIb and to activate Src.

A1 domain of VWF interaction with GPIb selectively activates Src and stimulates Src association with GPIb.

(A) After stimulation with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 20 μg/mL A1 domain of VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), platelets were solubilized with lysis buffer containing Complete. The lysates were divided into 2 equal volumes, which were subjected to either immunoprecipitation with anti-Src or anti-Lyn MoAbs, respectively. In vitro kinase assays were performed using enolase as exogenous substrate. The proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and quantified with a BAS 2000 phosphorimager. Equivalent precipitation of Src or Lyn was confirmed by immunoblotting as shown in the lower panel. The arrows represent the bands presumably derived from IgG heavy chain. (B) The level of enolase phosphorylation in anti-Src (♦) and anti-Lyn (▪) immunoprecipitates shown in panel A was quantified by densitometry, and represented as a fold-increase over the control (0 seconds). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments. (C) The samples were prepared as described in panel A and the subsequent lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIb MoAb. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs, respectively.

A1 domain of VWF interaction with GPIb selectively activates Src and stimulates Src association with GPIb.

(A) After stimulation with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 20 μg/mL A1 domain of VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), platelets were solubilized with lysis buffer containing Complete. The lysates were divided into 2 equal volumes, which were subjected to either immunoprecipitation with anti-Src or anti-Lyn MoAbs, respectively. In vitro kinase assays were performed using enolase as exogenous substrate. The proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and quantified with a BAS 2000 phosphorimager. Equivalent precipitation of Src or Lyn was confirmed by immunoblotting as shown in the lower panel. The arrows represent the bands presumably derived from IgG heavy chain. (B) The level of enolase phosphorylation in anti-Src (♦) and anti-Lyn (▪) immunoprecipitates shown in panel A was quantified by densitometry, and represented as a fold-increase over the control (0 seconds). The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments. (C) The samples were prepared as described in panel A and the subsequent lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIb MoAb. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs, respectively.

The physical association of Src with GPIb as well as its activation indicates that Src is the most likely candidate responsible for GPIb-related protein tyrosine phosphorylation events. However, despite Src activation, A1 domain of VWF interaction with GPIb failed to mediate downstream signaling events, such as tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain, Syk, or PLCγ2 (Figure4). Moreover, Syk and PLCγ2phosphorylation triggered by VWF-botrocetin was decreased in level and delayed in time course by cytochalasin D treatment (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that ligand binding of GPIb is able to activate Src kinase, but that its downstream signals require receptor clustering, which may elicit certain as yet unidentified signals that lead to the full activation of platelets.

A1 domain of VWF interaction with GPIb does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain, Syk, and PLCγ2.

In the presence of 6 μg/mL botrocetin, platelets were stimulated with either 20 μg/mL A1 domain of VWF or 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), respectively. The platelets were processed for precipitation with GST-Syk-SH2 (A), or for immunoprecipitation with anti-Syk (B) and anti-PLCγ2 (C) antibodies. Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed with an antiphosphotyrosine MoAb (pY; A, B-C upper panels). The membranes were then stripped and reprobed for Syk and PLCγ2 using the corresponding antibodies (B-C, lower panels).

A1 domain of VWF interaction with GPIb does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain, Syk, and PLCγ2.

In the presence of 6 μg/mL botrocetin, platelets were stimulated with either 20 μg/mL A1 domain of VWF or 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), respectively. The platelets were processed for precipitation with GST-Syk-SH2 (A), or for immunoprecipitation with anti-Syk (B) and anti-PLCγ2 (C) antibodies. Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed with an antiphosphotyrosine MoAb (pY; A, B-C upper panels). The membranes were then stripped and reprobed for Syk and PLCγ2 using the corresponding antibodies (B-C, lower panels).

Interaction of VWF with GPIb stimulates complex formation between Src, PI 3–kinase, and GPIb

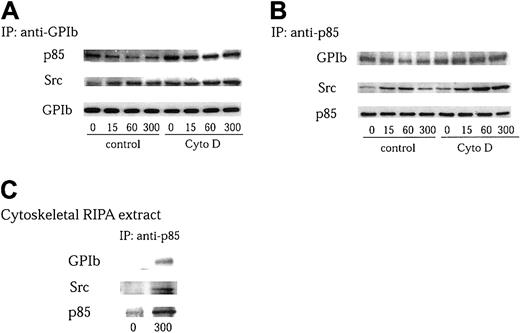

Although we found that Src associates with GPIb on stimulation, the effect of protease inhibitors implies that this association is probably indirect. Furthermore, the GPIb complex lacks motifs to which Src can bind. Recently, Munday et al15 reported that PI 3–kinase associates with GPIb in platelets. We therefore sought to determine whether Src, PI 3–kinase, and GPIb form a complex following GPIb stimulation. PI 3–kinase is a heterodimeric phospholipid kinase composed of a regulatory subunit, p85, and a catalytic subunit, p110.24,44 It is known that the p85 subunit coassociates with p110 at a ratio of 1:1 in platelets.45 Thus, the heterodimer of p85 and p110 PI 3–kinase can be obtained by immunoprecipitation with an anti-p85 antibody. GPIb and PI 3–kinase immunoprecipitates were analyzed separately by Western blotting with anti-Src and anti-p85, or anti-Src and anti-GPIb antibodies. As shown in Figure 5A-B, the association between p85 and GPIb decreased on VWF stimulation, which is in agreement with the report of Munday et al.15 However, the association between GPIb and Src, and that of PI 3–kinase and Src, increased as early as 15 seconds after stimulation with VWF plus botrocetin. These associations peaked at 1 minute followed by a decrease at 5 minutes (Figure 5A-B). Taking into account that VWF-GPIb interaction stimulates GPIb translocation to the cytoskeleton,46 it is possible that the decreased association between GPIb and PI 3–kinase is due to their relocation in a complex form to the cytoskeleton.15To test this possibility, the reorganization of the actin-based cytoskeleton was prevented by pretreatment with 1 μM cytochalasin D. As shown in Figure 5A-B, neither the recovery of PI 3–kinase in GPIb immunoprecipitates nor that of GPIb in p85 immunoprecipitates was altered on VWF stimulation in the presence of cytochalasin D, implying that GPIb constitutively associates with PI 3–kinase, and that the level of their association is maintained throughout platelet activation. On the other hand, cytochalasin D pretreatment augmented the level of association between Src and GPIb and that between Src and PI 3–kinase (Figure 5A-B), suggesting that Src translocates to the cytoskeleton in a complex form with GPIb and PI 3–kinase. Consistent with this conclusion, Src and GPIb were coprecipitated with anti-p85 antibody from RIPA extracts of the cytoskeleton of VWF-botrocetin–activated platelets, suggesting that Src, PI 3–kinase, and GPIb indeed form a complex after GPIb stimulation (Figure 5C). Taken together, these results suggest that PI 3–kinase constitutively associates with GPIb, and that GPIb-mediated platelet activation does not change the level of PI 3–kinase interaction with GPIb. Src, however, associates with GPIb-PI 3–kinase to form a complex in a stimulation-dependent manner, which is upstream of actin polymerization.

VWF-stimulated complex formation between Src, PI 3–kinase, and GPIb is upstream of actin polymerization.

(A-B) Platelets were preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.25% DMSO as control or 1 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D), and stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). The platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIb (A) and anti-p85 (B) antibodies, respectively. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by anti-Src, anti-p85, and anti-GPIb immunoblotting. (C) Platelets without pretreatment with cytochalasin D were stimulated for 5 minutes and lysed. The lysates were then fractionated as described in Figure 3B. The Triton-insoluble fractions were further lysed in RIPA buffer, and the RIPA extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-p85 antibody. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by anti-Src, anti-p85, and anti-GPIb immunoblotting.

VWF-stimulated complex formation between Src, PI 3–kinase, and GPIb is upstream of actin polymerization.

(A-B) Platelets were preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.25% DMSO as control or 1 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D), and stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). The platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIb (A) and anti-p85 (B) antibodies, respectively. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by anti-Src, anti-p85, and anti-GPIb immunoblotting. (C) Platelets without pretreatment with cytochalasin D were stimulated for 5 minutes and lysed. The lysates were then fractionated as described in Figure 3B. The Triton-insoluble fractions were further lysed in RIPA buffer, and the RIPA extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-p85 antibody. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by anti-Src, anti-p85, and anti-GPIb immunoblotting.

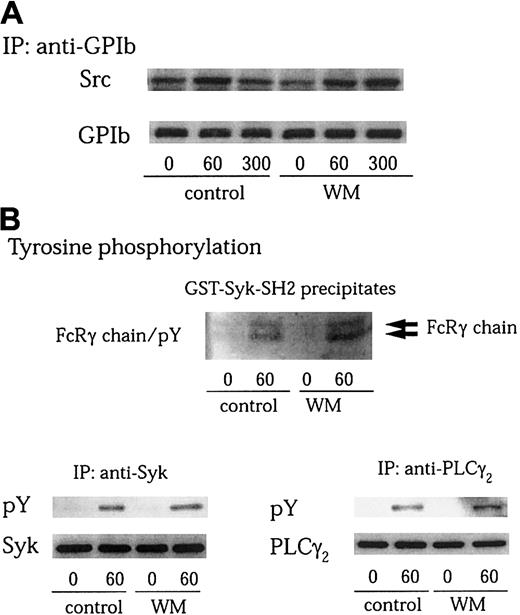

Involvement of PI 3–kinase in GPIb-mediated platelet activation is not dependent on its enzyme activity

PI 3–kinase plays a central role in the regulation of multiple cellular events.44,47 Many of these effects are mediated by the production of D-3 lipids that act to recruit various proteins to cell membranes. The products of PI 3–kinase also regulate the activity of a number of tyrosine kinases.16,19,24 Several lines of evidence indicate that PI 3–kinase is activated by GPIb-VWF interaction.7,15 We also found in this study that Src associates with the PI 3–kinase–GPIb complex on platelet activation. We therefore asked whether the enzyme activity of PI 3–kinase is required for GPIb-mediated Src activation. Wortmannin is known to inactivate the catalytic p110 subunit of PI 3–kinase by covalently modifying it at Lys802, a residue involved in phosphate transfer by this enzyme.48 Pretreatment of platelets with 100 nM wortmannin did not affect Src association with GPIb after GPIb-VWF interaction (Figure 6A). Additionally, it had no inhibitory effect on tyrosine phosphorylation of the FcRγ chain, Syk, and PLCγ2 stimulated by VWF plus botrocetin (Figure 6B). A structurally unrelated PI 3–kinase inhibitor, LY 294002, also failed to inhibit tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain, Syk, and PLCγ2, induced by GPIb-VWF interaction (data not shown). These data suggest that the functional role of PI 3–kinase in Src activation and the resultant downstream signaling and platelet aggregation induced by GPIb-VWF interaction are independent of its catalytic activity.

Wortmannin does not inhibit GPIb-stimulated Src association with GPIb, tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain, Syk, or PLCγ2.

(A-B) Platelets were preincubated with vehicle solution as the control or 100 nM wortmannin (WM) at 37°C for 10 minutes, and then activated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). GPIb was immunoprecipitated from lysates and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs (A). The cell lysates were precipitated with GST-Syk-SH2, anti-Syk, or anti-PLCγ2 antibodies, respectively. The precipitated proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. The membranes were immunoblotted for phosphotyrosine using 4G10 plus PY20 (B; pY). Then the membranes were stripped and reprobed for Syk and PLCγ2 using corresponding antibodies (B, lower panels).

Wortmannin does not inhibit GPIb-stimulated Src association with GPIb, tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain, Syk, or PLCγ2.

(A-B) Platelets were preincubated with vehicle solution as the control or 100 nM wortmannin (WM) at 37°C for 10 minutes, and then activated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). GPIb was immunoprecipitated from lysates and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Src and anti-GPIb MoAbs (A). The cell lysates were precipitated with GST-Syk-SH2, anti-Syk, or anti-PLCγ2 antibodies, respectively. The precipitated proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. The membranes were immunoblotted for phosphotyrosine using 4G10 plus PY20 (B; pY). Then the membranes were stripped and reprobed for Syk and PLCγ2 using corresponding antibodies (B, lower panels).

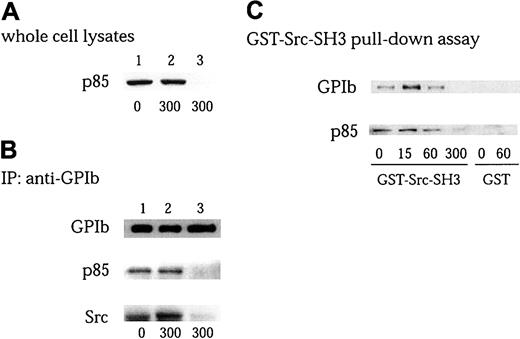

Association of Src with GPIb is mediated by p85/PI 3–kinase

The subunits of the GPIb complex, as well as its associated proteins, ABP-280 and 14-3-3ζ, all lack potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites and other related binding structures such as SH3 domains, proline-rich motifs, and SH2 domains. Thus, p85, which has 2 proline-rich motifs, is a good candidate to serve as a docking protein for Src. To test this hypothesis, we performed an immunodepletion experiment of p85/PI 3–kinase, as shown in Figure 7A-B. After platelets pretreated with cytochalasin D were activated, the platelets were lysed and then 2 rounds of immunoprecipitation were performed with anti-p85/PI3-kinase antibody. p85 was completely depleted in the whole cell lysates (Figure7A lane 3), and p85 could be no longer be detected in GPIb immunoprecipitates (Figure 7B lane 3 of blot for p85). Depletion of p85 completely eliminated Src recovery in GPIb immunoprecipitates (Figure7B lane 3 of blot for Src). There are no major changes in the amount of GPIb in studies between immunoprecipitation and immunodepletion (Figure7B lane 3 of blot for GPIb). These findings suggest that Src association with GPIb is mediated by PI 3–kinase, rather than GPIb, and that only a small population of GPIb is included in forming the GPIb-PI3-kinase/Src complex. We next used a GST-fusion protein of the Src SH3 domain to see whether Src and p85/PI 3–kinase association is mediated by the binding between the Src SH3 domain and p85/PI 3–kinase. As shown in Figure 7C, GPIb and p85 were detected to some extent in GST-Src-SH3 precipitates in the resting state, and their recovery increased on stimulation at 15 seconds. It was then followed by a decrease at 1 minute and a complete loss at 5 minutes. This phenomenon is compatible with the notion that on stimulation Src transiently associates with PI 3–kinase linked to GPIb and that they redistribute as a complex to the Triton-insoluble cytoskeleton (Figure5). These findings further suggest that PI 3–kinase functions as an adaptor protein to recruit Src to GPIb, independent of its catalytic activity.

Association of Src with GPIb is mediated by interaction of Src-SH3 with PI 3–kinase.

(A-B) Platelets pretreated with 1 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D) were stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). The platelet lysates without (lane 1, control; lane 2, after stimulation) or with (lane 3) p85 immunodepletion were examined for the presence of p85 by anti-p85 immunoblotting (A), and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GPIb MoAb (B). The immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-GPIb, anti-p85, and anti-Src antibodies, respectively. (C) Platelets were stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), the lysates were precipitated with 20 μg/mL GST-Src-SH3 or GST alone. The precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GPIb and anti-p85 antibodies, respectively.

Association of Src with GPIb is mediated by interaction of Src-SH3 with PI 3–kinase.

(A-B) Platelets pretreated with 1 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D) were stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds). The platelet lysates without (lane 1, control; lane 2, after stimulation) or with (lane 3) p85 immunodepletion were examined for the presence of p85 by anti-p85 immunoblotting (A), and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GPIb MoAb (B). The immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-GPIb, anti-p85, and anti-Src antibodies, respectively. (C) Platelets were stimulated with 6 μg/mL botrocetin plus 10 μg/mL VWF for the indicated time periods (seconds), the lysates were precipitated with 20 μg/mL GST-Src-SH3 or GST alone. The precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GPIb and anti-p85 antibodies, respectively.

Discussion

The findings presented in this study demonstrate for the first time that Src kinases physically associate with GPIb and that they are activated by the interaction between GPIb and VWF. In a previous report, we found that an unidentified tyrosine kinase activity coprecipitated with GPIb on VWF-GPIb interaction.5In this study, we modified the lysis buffer to include Complete, a mixture of protease inhibitors with activity toward a wide range of proteases. With the use of this new lysis buffer, we found that Src and Lyn associate with GPIb on VWF-GPIb interaction. This relative lability of the association between Src family kinases and GPIb implies that the mode of their interaction is probably indirect. We have found that a large amount of active Src was associated with GPIb after VWF-GPIb interaction, suggesting that interaction of VWF with GPIb may first stimulate Src association with GPIb, and consequently activate it. Alternatively, active Src may preferentially link to GPIb. This issue remains to be resolved.

On the other hand, even with the use of Complete, we still failed to detect an increase in Src activity in the Triton-soluble fraction of VWF-stimulated platelets. Previous studies have shown that clustering of GPIb receptors by multimeric VWF induces actin polymerization10 and stimulates Src and Lyn translocation to the reorganized cytoskeleton as an early event in platelet activation.5,32 In this study, we found that translocation of Src kinases was inhibited by pretreatment with cytochalasin D. This procedure allowed us to observe an increase in Src autophosphorylation and its kinase activity. Thus, the rapid redistribution of Src kinases appears to have resulted in an underestimate of the increased activity of Src in the Triton-soluble fraction. These findings also imply that GPIb-stimulated Src activation is not dependent on receptor clustering. This conclusion is at odds with the widely held notion that GPIb clustering is a prerequisite for its downstream signaling. To address this issue, we used recombinant A1 domain instead of intact VWF to stimulate platelets, because the monomeric A1 domain would not be expected to cluster GPIb with subsequent reorganization of actin filaments. With platelets stimulated by A1 domain plus botrocetin, Src rather than Lyn is selectively activated in a time-dependent manner. Moreover, A1 domain plus botrocetin also stimulates Src association with GPIb, demonstrating that binding of the A1 domain alone to GPIb is indeed sufficient to activate Src. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing that the interaction between GPIb and VWF specifically activates Src without receptor clustering. Given that PP1, a specific inhibitor of Src family kinases, completely blocks tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk, LAT, PLCγ2, and the ITAM-containing proteins, FcRγ chain and FcγRIIA,6,12 13 it is probable that Src activation constitutes the main pathway for GPIb-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. In contrast, Lyn activation was not observed on GPIb stimulation, especially within the first 5 minutes, implying that Lyn has little, if any, functional role in GPIb signaling.

The VWF multimer is a major physiologic ligand for GPIb. Its multivalency is believed to induce GPIb clustering on VWF-GPIb interaction, and it is widely held that GPIb clustering is a prerequisite for platelet activation. In this study, we found that GPIb ligand binding without receptor clustering, as induced by A1 domain plus botrocetin, is sufficient to initiate intracellular signaling such as Src association with GPIb as well as Src activation. However, it was insufficient to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the FcRγ chain, Syk, and PLCγ2. In accord with these findings, cytochalasin D, which inhibits receptor clustering, markedly attenuated VWF-botrocetin–stimulated Syk and PLCγ2 tyrosine phosphorylation (data not shown). What additional signal elicited by GPIb clustering is required for the full activation of platelets awaits further investigation.

The constituents of the GPIb-IX-V complex lack tyrosine-phosphorylated residues and other special binding motifs such as proline-rich domains and SH2 domains, which would allow the binding of Src to GPIb. Thus, it is likely that the association of Src with GPIb is not direct, but is mediated by another signaling molecule. This is supported by the finding that recovery of Src in GPIb immunoprecipitates was only made possible by use of a lysis buffer containing Complete, although the target proteases inhibited by Complete in this setting remain unknown. A potential role for PI 3–kinase in GPIb signaling has been suggested by the observation that VWF binding to GPIb can induce the cytoskeletal association and activation of the p85/p110 form of PI 3–kinase.7 More interestingly, PI 3–kinase has been shown to associate with GPIb.15 In this study, we detected a complex of Src, PI 3–kinase, and GPIb in lysates of platelets activated by VWF and botrocetin, suggesting that PI 3–kinase links Src with GPIb. On GPIb stimulation, the complex of GPIb, PI 3–kinase, and Src appears to translocate to the cytoskeleton, a conclusion supported by the observation that Src and GPIb were recovered in p85 immunoprecipitates of RIPA extracts of cytoskeletal proteins. We then asked what could be the mode of interaction between GPIb, PI 3–kinase, and Src. On GPIb stimulation, PI 3–kinase recovered in GPIb immunoprecipitates decreased in amount. Correspondingly, GPIb recovered in PI 3–kinase immunoprecipitates was also reduced, suggesting that these 2 molecules translocate to the cytoskeleton in a complex. When their translocation to the cytoskeleton was blocked by cytochalasin D pretreatment, the level of their association remained constant, irrespective of stimulation, which implies that GPIb and PI 3–kinase constitutively associate and that their association remains constant even after platelet activation. On the other hand, Src association with GPIb or PI 3–kinase is dynamically dependent on GPIb stimulation, especially in platelets pretreated with cytochalasin D. These findings taken together suggest that Src is recruited to an already-existing complex of GPIb and PI 3–kinase on platelet activation.

It is of note that the overall recovery of GPIb in anti-GPIb immunoprecipitates was virtually the same from control and PI 3–kinase–depleted platelet lysates (Figure 7B), suggesting that only a small portion of the GPIb molecules participate in the formation of the GPIb/PI 3–kinase/Src complex. It is possible that the rest of GPIb molecules are linked to signaling molecules other than PI 3–kinase and Src, and that the GPIb/PI 3–kinase/Src signaling constitutes only one of several signaling pathways involved in GPIb-related platelet activation. It is also possible that only a portion of the GPIb molecules are recruited to form a complex with Src/PI 3–kinase at a given moment, taking into consideration the fast on and off rate of the GPIb-VWF interaction. Alternatively, the limited association of GPIb and PI 3–kinase may simply reflect their equilibrium redistribution as a consequence of PI 3–kinase immunodepletion of the platelet lysate and the relative avidity of their association. Although a small portion of the GPIb molecules appear to participate in the signaling pathway related to PI 3–kinase and Src, we suggest that signaling through Src/Fcγ chain may also play a major role in the tyrosine phosphorylation–related pathway, because tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ2 or LAT by VWF-botrocetin is diminished in platelets pretreated with a Src kinase–selective inhibitor, PP1, or in the Fcγ chain–deficient platelets.12

We then sought to determine which molecule, GPIb or PI 3–kinase, directly binds Src. Using an immunodepletion method with anti-p85/PI 3–kinase antibody, we found that PI 3–kinase and Src always coexist in GPIb immunoprecipitates, which suggests that Src binds to PI 3–kinase, but not to GPIb.

PI 3–kinase plays a central role in the regulation of multiple cellular events, such as cell growth, vesicular trafficking, cytoskeletal organization, proliferation, and apoptosis.44,47 In particular, a number of tyrosine kinases appear to be regulated by PI 3–kinase via its production of D-3 lipids that act to recruit proteins to cell membranes. In this study, wortmannin had no effects on GPIb-mediated Src activation, the formation of the GPIb/Src/PI 3–kinase complex, or on tyrosine phosphorylation of the FcRγ chain, Syk, and PLCγ2. Thus, the enzymatic activity of PI 3–kinase does not appear to be required in this setting. It is known that the p85 subunit of PI 3–kinase has several motifs that recruit signaling proteins. In some cells, it serves as an adaptor protein to regulate cell function independent of PI 3–kinase enzymatic activity.49 The association between Src and p85 may theoretically be mediated by 2 distinct molecular interactions: one between the phosphotyrosine residues on p85 and the Src-SH2 domain, and the second between the p85 proline-rich sequences and the Src-SH3 domain. In this study, we found that p85 was not tyrosine-phosphorylated on VWF-botrocetin stimulation (data not shown). Using a GST-Src-SH3 pull-down assay, however, we found Src association with the GPIb–PI 3–kinase complex is mediated by the Src-SH3 domain. Thus, the present data suggest that p85 serves as a scaffolding protein to recruit Src to GPIb. Indeed, association of Src with the p85 subunit of PI 3–kinase via its SH3 domain is a common mode of assemblage and contributes to intracellular targeting of Src in other cells.19,44 Based on these findings, we suggest that PI 3–kinase constitutively associates with GPIb and that ligand binding of GPIb mediates a conformational change of the GPIb/p85/PI 3–kinase complex, which recruits Src. Previous studies have shown that the association of PI 3–kinase with GPIb is mediated by 14-3-3ζ, which plays a critical role in GPIb-dependent activation of the integrin, αIIbβ3.50Whether p85/PI 3–kinase–dependent association of Src with GPIb may also be regulated by 14-3-3ζ remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates for the first time that VWF-GPIb interaction stimulates Src association with GPIb and Src activation. The GPIb-associated p85 subunit of PI 3–kinase functions as a scaffolding protein, recruiting Src to GPIb, thereby leading to its activation. The physical interaction of Src with GPIb and its early activation imply that Src activation constitutes the paramount pathway for GPIb-related tyrosine phosphorylation events.

We are grateful to Prof Y. Fujimura for kindly supplying jararaca-GPIb-binding protein, Dr M. Handa for the generous donation of anti-GPIb MoAb, WGA3, Dr C.-L. Law for the kind gift of GST-Syk-SH2, and Dr A. Dunn for provision of the GST-Src-SH3 construct.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 29, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0806.

Y.W. and N.A. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Yukio Ozaki, Department of Clinical and Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Yamanashi, 1110 Shimokatoh, Tamaho, Nakakoma, Yamanashi 409-3898, Japan; e-mail:yozaki@res.yamanashi-med.ac.jp.