To exploit a novel strategy to regulate T cell–mediated immunity, we established human and murine modified dendritic cells (DCs) with potent immunoregulatory properties (designed as regulatory DCs), which displayed moderately high expression levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and extremely low levels of costimulatory molecules compared with their normal counterparts. Unlike human normal DCs, which caused the activation of allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, human regulatory DCs not only induced their anergic state but also generated CD4+ or CD8+regulatory T (Tr) cells from their respective naive subsets in vitro. Although murine normal DCs activated human xenoreactive T cells in vitro, murine regulatory DCs induced their hyporesponsiveness. Furthermore, transplantation of the primed human T cells with murine normal DCs into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice enhanced the lethality caused by xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease (XGVHD), whereas transplantation of the primed human T cells with murine regulatory DCs impaired their ability to cause XGVHD. In addition, a single injection of murine regulatory DCs following xenogeneic or allogeneic transplantation protected the recipients from the lethality caused by XGVHD as well as allogeneic acute GVHD. Thus, the modulation of T cell–mediated immunity by regulatory DCs provides a novel therapeutic approach for immunopathogenic diseases.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are unique professional major antigen (Ag)–presenting cells (APCs) capable of stimulating naive T cells in the primary immune response and are more potent APCs than monocytes/macrophages or B cells.1

The treatment of normal immature DCs (iDCs) with interleukin 10 (IL-10) caused a down-regulation in the expressions of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and costimulatory molecules, leading to a suppression of their T cell–stimulatory ability2 as well as an induction of anergic T cells.3,4 Recently, repetitive stimulation of human naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic normal iDCs not only induced T-cell anergy but also generated CD4+CD25+CD152+regulatory T (Tr) cells from their naive subsets.5Furthermore, a single injection of antigenic peptide-pulsed normal iDCs led to an appearance of Ag-specific IL-10–producing CD8+ T cells in healthy individuals.6 However, the clinical application of self Ag-pulsed or allogeneic/xenogeneic normal iDCs may not be suitable for the treatment of autoimmune diseases or for allogeneic/xenogeneic organ transplantation because the injected normal iDCs are not likely to remain immature in vivo after recirculation and home into the damaged tissue where chronic inflammation is always present.7 Therefore, further development of DCs with potent negative regulatory ability for T cells is thought to facilitate their use for the prevention and the treatment of immunopathogenic diseases.

To exploit a novel strategy involving the use of DCs for the regulation of T cell–mediated immunity, we examined the effect of human and murine modified DCs with potent immunoregulatory properties (designed as regulatory DCs) on allogeneic/xenogeneic T-cell responses in vivo and in vitro.

Materials and methods

Mice, media, and reagents

Female BALB/c mice (H-2d, 4-6 weeks of age) and C57/BL6 mice (H-2b, 4-6 weeks of age) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC). Female C.B.-17-scid (severe combined immunodeficient; SCID) mice (H-2d, 4-6 weeks of age) were purchased from Clea Japan (Tokyo, Japan). They were maintained according to institutional guidelines under approved protocols in the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science (School of Medicine, Kagoshima University, Japan). Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), human IL-2, human IL-4, human IL-10, human tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), human transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), murine GM-CSF, and murine IL-10 were purchased from Pepro Tech (London, United Kingdom). The medium used throughout was RPMI 1640 (for T cells and DCs; Sigma, St Louis, MO) or Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; for fibroblasts; Sigma) supplemented with an antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco).

Cell preparations

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from 20 healthy volunteers were resuspended in culture medium and allowed to adhere to the tissue-culture dish (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 2 hours at 37°C, nonadherent cells were removed by a vigorous washing and adherent cells (> 90% CD14+ cells) were used as monocytes. Monocytes were cultured with human GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) and human IL-4 (50 ng/mL) for 7 days.2,4 Following this procedure, nonadherent cells were collected and subjected to the negative selection with anti-CD2 monoclonal antibody (mAb)–conjugated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) and anti-CD19 mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal) to deplete CD2+ cells (T cells and natural killer [NK] cells) and CD19+ cells (B cells). The resultant cells were used as normal iDCs. Similarly, human modified/regulatory iDCs were also generated from monocytes cultured with human GM-CSF (50 ng/mL), human IL-4 (50 ng/mL), human IL-10, and human TGF-β1 (each 50 ng/mL) for 7 days. Human IL-10–treated iDCs were prepared from the culture of normal iDCs with human IL-10 (50 ng/mL) for 3 days.4 These cells were washed 3 times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after the generation to prevent carryover of cytokines, and were cultured with human TNF-α (50 ng/mL) in the tissue-culture dish for another 3 days for the preparation of mature DCs (mDCs). These DC preparations were typically more than 95% pure as indicated by anti–HLA-DR mAb (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) staining, and contained less than 0.1% T cells, B cells, monocytes/macrophages, and NK cells as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

The generation of murine normal DCs was performed according to the previous report8 with some modifications. Briefly, bone marrow (BM) cells (BALB/c mice) were cultured with murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) in a bacteriologic Petri dish (BIO-BIK, Tokyo, Japan) for 6 days. Nonadherent cells were collected and subjected to the negative selection with mAbs to Ly-76, CD2, B220, CD14, and Ly-6G (all from BD Pharmingen) plus sheep antirat IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal). The resultant cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS after the generation to prevent carryover of cytokines and stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (1 μg/mL; Sigma) in a bacteriologic Petri dish for 2 days. Similarly, murine modified/regulatory DCs were also obtained by culturing BM cells with murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL), murine IL-10 (20 ng/mL), and human TGF-β1 (20 ng/mL) for 6 days followed by lipopolysaccharide (1 μg/mL) for 2 days. These DC preparations were typically more than 90% pure as indicated by anti–I-A/I-E mAb (BD Pharmingen) staining, and contained less than 0.1% erythrocytes, T cells, B cells, monocytes/macrophages, NK cells, and neutrophils as assessed by FACS analysis.

Human skin fibroblasts were prepared from epidermal skin tissues after obtaining informed consent from 2 different healthy volunteers.

Human total T cells were purified from PBMCs obtained from 20 healthy volunteers with a T-cell negative isolation kit (Dynal).9Subsequently, naive CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were negatively selected from total T cells with anti-CD8 mAb or anti-CD4 mAb (each from BD Pharmingen) in combination with anti-CD45RO mAb (BD Pharmingen) plus goat antimouse IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal). These T-cell preparations were typically more than 98% pure as indicated by FACS analysis. For preparation of human Ag-specific CD8+ T cells, PBMCs were cocultured with irradiated (15 Gy from a 137Cs source, MBR-1505R2, Hitachi Medical, Tokyo, Japan) allogeneic fibroblasts derived from an unrelated donor (donor no. 1) in the presence of human IL-2 (100 U/mL) for 2 weeks,4 and CD8+ T cells were positively selected with a CD8+ isolation kit (Dynal) from the coculture.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with the following mAbs to human and murine markers: CD1a and CD83 (Coulter Immunology, Hialeah, FL); CD3, CD11c, CD25, CD28, CD40, CD45, CD80, CD86, CD152, CD154, HLA-A/B/C, I-Kd, and isotype-matched control mAb (all from BD Pharmingen); and anti–E-cadherin (E-cad) mAb (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA).2,4 For analysis of the intracellular expression of cytokines,4 permeabilized/fixed cells were stained with mAbs to human IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and interferon γ (IFN-γ; all from BD Pharmingen) following stimulation with plate-bound antihuman CD3 mAb (10 μg/mL; BD Pharmingen) plus soluble antihuman CD28 mAb (10 μg/mL; BD Pharmingen; for CD4+ T cells) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 20 ng/mL; Sigma) plus Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (500 ng/mL; Sigma; for CD8+ T cells) for 6 hours. Fluorescence staining was analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA), and data are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Allogeneic/xenogeneic priming of human T cells in vitro

Human naive CD4+ T cells or Ag-specific CD8+ T cells (5 × 106) were primed with irradiated (15 Gy) human allogeneic DCs (5 × 103 to 5 × 105) for 3 days, and these T-cell subsets were negatively selected with antihuman CD11c mAb (BD Pharmingen) plus goat antimouse IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads. These T-cell preparations contained less than 0.1% CD11c+ cells as assessed by FACS analysis. For in vitro xenogeneic priming, human T cells (5 × 107) were primed with irradiated (15 Gy) murine DCs (5 × 106, H-2d) in the presence or absence of human IL-2 (100 U/mL) for 3 days. After incubation, human T cells were negatively selected with anti–I-Kd mAb (BD Pharmingen) plus goat antimouse IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads. These T-cell preparations contained less than 0.1% I-Kd+ cells as assessed by FACS analysis. Cells were rested in medium containing human IL-2 (10 U/mL) for 3 days before use.

Mixed leukocyte reaction

Human T-cell subsets (105) were cultured in 96-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) with various numbers of irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic/xenogeneic DCs in the presence or absence of human IL-2 (100 U/mL). Thymidine incorporation was measured as counts per minute (cpm) for the indicated days after an 18-hour pulse with [3H]-thymidine.2 4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte assay

Ag-specific CD8+ T cells (5 × 105) were cultured with NaCrO4 (100 μCi/106 cells [3.7 MBq]; NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA)–labeled allogeneic fibroblasts derived from 2 different donors (104) for 4 hours. The supernatants were harvested, the radioactivity (cpm) was measured, and the percentage of specific lysis was calculated.4

Preparation of Tr-cell subsets

Human CD4+CD45RA+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic normal mDCs (5 × 105) for 3 days, and Ag-primed CD4+ T cells were obtained from the coculture by the depletion of DCs as described in “Allogeneic/xenogeneic priming of human T cells in vitro.” Human CD4+CD45RA+ T cells (5 × 106) were also cultured with irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic regulatory iDCs (5 × 105) for 5 days, and T cells were negatively selected by the depletion of DCs. CD4+CD25+ T cells or CD4+CD25− T cells were then selected with anti-CD25 mAb (BD Pharmingen) plus goat antimouse IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads, and they were typically more than 95% pure as indicated by FACS analysis.

Human naive CD8+ T cells (5 × 106) were cocultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (5 × 105) or regulatory iDCs (5 × 105) for 5 days, and CD8+ T cells were negatively selected by the depletion of DCs. Subsequently, CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells were selected using antihuman CD28 mAb (BD Pharmingen) plus goat antimouse IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads.

The removal of the immunomagnetic beads from the selected cells was performed by competitive detachment with mouse serum for 4 hours, and they rested in medium for 16 hours according to the manufacturer's instruction manual. After incubation, the residual immunomagnetic beads were removed by the magnetic particle concentrator (MPC-S, Dynal).

Analysis of Tr-cell function

Ag-primed CD4+ T cells or CD4+CD25+ T cells (105) were cultured with irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of different numbers of CD4+CD25+ T cells or Ag-primed CD4+T cells in 96-well plates. In another experiment, Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of different numbers of CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells in 96-well plates. The proliferative response of T cells was evaluated on day 5 by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Alternatively, human CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells (106) plus irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic normal mDCs (105) were either added directly to the coculture of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (106) with irradiated (15 Gy) allogeneic normal mDCs (105) in 24-well plates (Costar) or were placed separately in 24-well Transwell cell culture chambers (Millicell, 0.4-μm pore size; Millipore, Bedford, MA) in the same well for 4 days. Following depletion of DCs, total T cells (105/well) were transferred to 96-well plates. The proliferative response was measured after an additional 18-hour pulse with [3H]-thymidine.

A model of XGVHD in SCID mice engrafted with human peripheral blood lymphocytes and murine allogeneic acute GVHD

For xenogeneic transplantation, SCID mice (5 animals in each group) were pretreated 1 day prior to the transplantation with a single dose (lyophilized Ab was resuspended in 1 mL PBS, and 20 μL/mouse was given by intraperitoneal injection) of anti-asialo GM1 antiserum (the protein concentration was 10 mg/mL, WAKO, Osaka, Japan).10 Immediately prior to the transplantation, SCID mice were exposed to a sublethal total body irradiation (5 Gy/mouse).10 Subsequently, unprimed human T cells or xenogeneic primed human T cells prepared as described (4 × 107/mouse) were intravenously injected into SCID mice under sterile conditions. For murine allogeneic transplantation, SCID mice received a lethal total body irradiation (10 Gy/mouse), and the recipients were injected with BM cells (H-2b, 2 × 107/mouse) plus spleen mononuclear cells (H-2b, 2 × 107/mouse). In a parallel experiment, SCID mice engrafted with human peripheral blood lymphocytes (hu-PBL-SCID mice; 5 animals in each group) or SCID mice underwent allogeneic transplantation (5 animals in each group), receiving a single intravenous injection of murine normal or modified/regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse) 2 days after allogeneic/xenogeneic transplantation. Alternatively, intravenous injections of human IL-2 (104 U/mouse) were performed on days 3, 5, and 7 after xenogeneic transplantation in hu-PBL-SCID mice receiving murine modified/regulatory DCs (5 animals in each group). Recipients were monitored once every day from the day of transplantation until they died naturally of xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease (XGVHD), and the survival (%) was calculated as a function of time. In another experiment, hu-PBL-SCID mice (5 animals in each group) were killed on day 10 after xenogeneic transplantation to obtain spleen tissue. Spleen mononuclear cells were obtained by centrifugation with the use of Histopaque-1080 (Sigma), and the interphase fraction was recovered. The engraftment of human T cells in spleen in hu-PBL-SCID mice was then accessed by FACS analysis with mAbs to human CD3 and CD45. Transplanted human T cells were also negatively selected from spleen mononuclear cells with anti–I-Kd mAb plus goat antimouse IgG mAb-conjugated immunomagnetic beads. Cells were rested in medium containing human IL-2 (10 U/mL) before use.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean values ± SD of all individual experiments. All analyses for statistically significant differences were performed with the Student paired t test or Mann-Whitney U test. P < .01 was considered significant.

Results

Human modified DCs act as regulatory DCs to induce T-cell anergy

Modified iDCs expressed both the DC-marker (CD1a and CD11c) and the Langerhans cell marker (E-cad), but not the monocyte/macrophage-marker (CD14) as shown in Figure1A. On the other hand, they showed moderately high expression levels of MHC molecules (HLA-A/B/C and HLA-DR), whereas they exhibited extremely low levels of costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, and CD86) as compared with normal iDCs (Figure 1B-D). On stimulation with TNF-α, CD83 was detected, whereas the DC and the Langerhans cell markers were down-regulated (Figure 1A). In addition, the expression levels of MHC and costimulatory molecules were changed to various degrees following this stimulation (Figure 1B-D). We also observed that modified DCs were less effective for the activation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells than normal DCs and IL-10–treated iDCs (Figure 2A-B).

Phenotypic profile of human modified DCs.

(A-B) Cells were stained with the stated mAbs against markers for the DC family molecules (A) and MHC and costimulatory molecules (B) or isotype-matched mAbs, and cell surface expression was analyzed by FACS. Data are represented by a histogram in which cells were stained with the stated mAbs (thick lines) or isotype-matched mAbs (thin lines). The values shown in the flow cytometry profiles are MFI. The results are representative of 10 experiments with similar results. (C) The percent positive cells for MHC and costimulatory molecules were expressed as mean values ± SD of 10 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with the respective iDCs by Student paired t test. (D) The expression levels of MHC and costimulatory molecules were expressed as MFI ± SD of 10 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with the respective iDCs or among groups by Student paired ttest.

Phenotypic profile of human modified DCs.

(A-B) Cells were stained with the stated mAbs against markers for the DC family molecules (A) and MHC and costimulatory molecules (B) or isotype-matched mAbs, and cell surface expression was analyzed by FACS. Data are represented by a histogram in which cells were stained with the stated mAbs (thick lines) or isotype-matched mAbs (thin lines). The values shown in the flow cytometry profiles are MFI. The results are representative of 10 experiments with similar results. (C) The percent positive cells for MHC and costimulatory molecules were expressed as mean values ± SD of 10 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with the respective iDCs by Student paired t test. (D) The expression levels of MHC and costimulatory molecules were expressed as MFI ± SD of 10 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with the respective iDCs or among groups by Student paired ttest.

We examined the ability of allogeneic modified DCs to induce T-cell anergy. The primed naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic normal DCs showed vigorous response to the same donor-derived normal mDCs (Figure 2A). In contrast, the primed naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic-modified DCs were hyporesponsive to further stimulation with the same donor-derived normal mDCs, and the addition of IL-2 to a second culture partly enhanced this response (Figure 2A). Similar results were observed when total CD4+ T cells were used as the responder cells, and the degree of modified DC-induced T-cell hyporesponsiveness was higher than that of IL-10–treated iDCs (Figure 2B).

Human regulatory DCs induce T-cell anergy in alloreactive T cells.

(A) Human naive CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor or unrelated donor in the presence or absence of human IL-2 in a second coculture. The proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs under each set of experimental conditions by Student paired t test. (B) Human total CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with the indicated types of allogeneic DCs (104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human total CD4+T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with the indicated types of allogeneic DCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor in a second coculture, and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs under each set of experimental conditions by Student paired t test. (C) Human naive CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (103-104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 104 to 5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor in a second coculture. The proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs under each set of experimental conditions by Student paired t test. (D) Human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor. The proliferative response was measured on the indicated days. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs by Student paired t test. (E) Human naive CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently cultured in medium alone (none) or restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of allogeneic normal or modified DCs (103-104) in a second coculture. The proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs in second coculture by Student pairedt test. (F) Human allogeneic Ag-specific CD8+ T cells (5 × 106), which were obtained from the primed PBMCs with allogeneic fibroblasts (donor no. 1), were cocultured with or without allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 103 to 5 × 105) derived from the indicated donors (no. 1 or 2) for 3 days. These CD8+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (5 × 105) were subsequently subjected to a cytotoxicity assay against the allogeneic fibroblasts (104) derived from the indicated donors (no. 1 or 2). The value of spontaneous release cpm was less than 10% of the total release cpm. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with allogeneic Ag-specific CD8+ T cells alone by Student paired ttest.

Human regulatory DCs induce T-cell anergy in alloreactive T cells.

(A) Human naive CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor or unrelated donor in the presence or absence of human IL-2 in a second coculture. The proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs under each set of experimental conditions by Student paired t test. (B) Human total CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with the indicated types of allogeneic DCs (104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human total CD4+T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with the indicated types of allogeneic DCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor in a second coculture, and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs under each set of experimental conditions by Student paired t test. (C) Human naive CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (103-104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 104 to 5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor in a second coculture. The proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs under each set of experimental conditions by Student paired t test. (D) Human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) generated from same donor. The proliferative response was measured on the indicated days. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs by Student paired t test. (E) Human naive CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. In another experiment, human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. These CD4+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (105) were subsequently cultured in medium alone (none) or restimulated with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of allogeneic normal or modified DCs (103-104) in a second coculture. The proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs in second coculture by Student pairedt test. (F) Human allogeneic Ag-specific CD8+ T cells (5 × 106), which were obtained from the primed PBMCs with allogeneic fibroblasts (donor no. 1), were cocultured with or without allogeneic normal or modified DCs (5 × 103 to 5 × 105) derived from the indicated donors (no. 1 or 2) for 3 days. These CD8+ T cells were then rescued, and cells (5 × 105) were subsequently subjected to a cytotoxicity assay against the allogeneic fibroblasts (104) derived from the indicated donors (no. 1 or 2). The value of spontaneous release cpm was less than 10% of the total release cpm. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with allogeneic Ag-specific CD8+ T cells alone by Student paired ttest.

Furthermore, allogeneic modified DCs induced anergic CD4+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C), and they retained the hyporesponsiveness at least for 2 weeks (Figure 2D). In addition, the primed CD4+ T cells with allogeneic-modified DCs exhibited a weaker response to the unrelated donor-derived allogeneic normal mDCs in a second culture than those primed with allogeneic normal DCs (Figure 2A).

We also examined the effect of modified DCs on allogeneic normal mDC-mediated activation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells (Figure2E). The addition of allogeneic normal mDCs, but not normal iDCs, to the coculture of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells with normal mDCs slightly enhanced their response, whereas allogeneic-modified DCs significantly suppressed this response in a dose-dependent manner.

We further tested the effect of allogeneic-modified DCs on cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells (Figures 2F). These CD8+ T cells showed cytotoxicity only against allogeneic fibroblasts (donor no. 1) used in their generation, indicating that their cytotoxicity was Ag specific. Stimulation with allogeneic normal mDCs, but not normal iDCs, enhanced their CTL activity, whereas treatment with allogeneic-modified DCs suppressed it in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, little or no change in CTL activity was observed when they were treated with allogeneic DCs derived from unrelated donor (donor no. 2) to allogeneic fibroblasts used in their generation, indicating that their regulations were Ag specific. Similar results were observed in other allogeneic combinations (data not shown).

Collectively, human modified DCs were potent regulators for alloreactive effector T cells, and we referred to modified DCs as regulatory DCs.

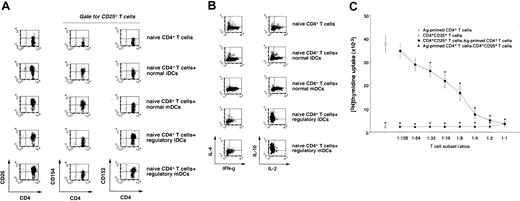

Human regulatory DCs induce CD4+CD25+Tr cells

CD4+CD25+ T cells reportedly act as Tr cells to suppress the responses of alloreactive or self-reactive CD4+ T cells in an Ag-nonspecific manner, and this T-cell subpopulation is supposed to maintain immunologic self-tolerance or control autoimmunity.11-13 A single stimulation with allogeneic regulatory DCs predominantly generated CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD152+ T cells from naive CD4+T cells, whereas allogeneic normal DCs induced CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD154+ T cells (Figure3A). We also observed that a large proportion of CD4+CD25+ T cells expressed CD152 (data not shown). On the other hand, IL-10–producing CD4+T cells were increased in the primed CD4+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs, whereas IFN-γ– and IL-2–producing CD4+ T cells were increased in the primed CD4+T cells with allogeneic normal DCs as compared with unprimed CD4+ T cells (Figure 3B).

Characterization of CD4+CD25+ T cells generated from the primed human naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs.

(A-B) Human allogeneic naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or regulatory DCs (5 × 105) for 5 days, and CD4+ T cells isolated from the coculture were assayed for phenotype (A) and cytokine profile (B) by FACS. The results are representative of 5 experiments with similar results, and data are represented by a dot plot. (C) Human Ag-primed CD4+ T cells were isolated from the coculture of human naive CD4+T cells (5 × 106) with allogeneic normal mDCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. CD4+CD25+T cells were isolated from the coculture of human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) with allogeneic regulatory iDCs (5 × 105) for 5 days. Human Ag-primed CD4+ T cells or CD4+CD25+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of different numbers of CD4+CD25+ T cells or Ag-primed CD4+T cells, and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs by Student paired ttest. Error bars express SD of mean values.

Characterization of CD4+CD25+ T cells generated from the primed human naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs.

(A-B) Human allogeneic naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or regulatory DCs (5 × 105) for 5 days, and CD4+ T cells isolated from the coculture were assayed for phenotype (A) and cytokine profile (B) by FACS. The results are representative of 5 experiments with similar results, and data are represented by a dot plot. (C) Human Ag-primed CD4+ T cells were isolated from the coculture of human naive CD4+T cells (5 × 106) with allogeneic normal mDCs (5 × 105) for 3 days. CD4+CD25+T cells were isolated from the coculture of human naive CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) with allogeneic regulatory iDCs (5 × 105) for 5 days. Human Ag-primed CD4+ T cells or CD4+CD25+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of different numbers of CD4+CD25+ T cells or Ag-primed CD4+T cells, and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs by Student paired ttest. Error bars express SD of mean values.

To examine the function of CD4+CD25+ T cells generated from the primed naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory iDCs, we examined their effect on allogeneic normal mDC-induced activation of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (Figure 3C). Ag-primed CD4+ T cells vigorously responded to allogeneic normal mDCs, whereas CD4+CD25+ T cells exhibited a poor response. In addition, CD4+CD25+ T cells suppressed the response of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells to allogeneic normal mDCs in a dose-dependent manner. However, we did not observe a dose-response relationship in which Ag-primed CD4+ T cells overcame the suppressive effect of CD4+CD25+ T cells when CD4+CD25+ T cells were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs in the presence of increasing numbers of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells, indicating that this suppressive effect may not be due to their simple competition for allogeneic normal mDCs. We also observed that the separation of CD4+CD25+T cells and Ag-primed CD4+ T cells abolished their inhibitory effect, and the addition of IL-2 restored the response of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells at least partially, whereas neutralizing Abs against IL-10 or TGF-β did not reverse their inhibitory effect (data not shown). In addition, CD4+CD25+ T cells showed a more potent inhibitory effect on the response of naive CD4+ T cells to allogeneic normal mDCs than that of naive CD4+ T cells to other donor-derived allogeneic normal mDCs by approximately 2-fold (data not shown), indicating that CD4+CD25+ T cells cause Ag-specific and Ag-nonspecific suppressions. These results indicate that regulatory DCs could efficiently generate CD4+CD25+ Tr cells from naive CD4+ T cells.

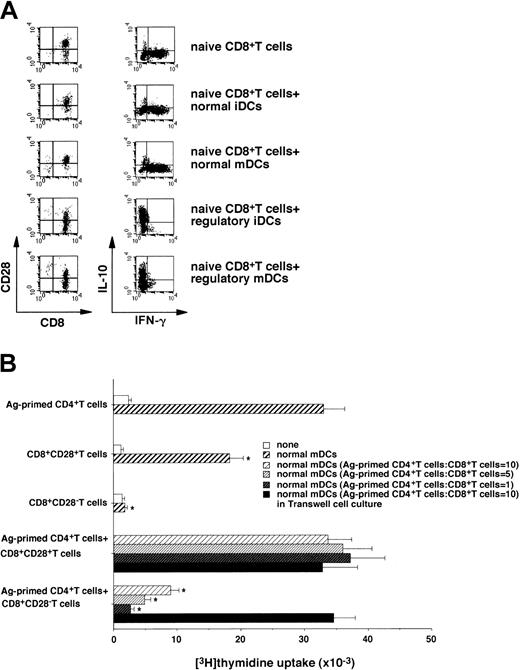

Human regulatory DCs induce CD8+CD28−Tr cells

Serial stimulations of human naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic/xenogeneic APCs reportedly induced the generation of IFN-γ–producing CD8+CD28− Tr cells regulating the response of CD4+ T cells.14-16On the other hand, a single injection of antigenic peptide-pulsed normal iDCs into humans induced peptide-specific CD8+ T cells producing IL-10.6 The coculture of naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs induced CD8+ CD28− T cells, whereas allogeneic normal DCs preferentially generated CD8+CD28+ T cells (Figure 4A). In addition, IL-10–producing CD8+ T cells were increased in the primed CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs, whereas IFN-γ–producing CD8+ T cells were increased in the primed CD8+ T cells with allogeneic normal mDCs as compared with unprimed CD8+ T cells (Figure 4A).

Characterization of CD8+CD28− T cells generated from the primed human naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs.

(A) Human allogeneic naive CD8+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or regulatory DCs (5 × 105) for 5 days, and CD8+ T cells isolated from the coculture were assayed for phenotype (left panel) and cytokine profile (right panel) by FACS. The results are representative of 5 experiments with similar results; data are represented by a dot plot. (B) CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells were isolated from the coculture of human naive CD8+ T cells (5 × 106) with allogeneic normal mDCs or regulatory iDCs (5 × 106) for 5 days. Ag-primed CD4+ T cells, CD8+CD28+ T cells, or CD8+CD28− T cells (105) were cultured with or without allogeneic normal mDCs (104). In another experiment, Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of different numbers of CD8+CD28+ T cells and CD8+CD28− T cells in 96-well plates, and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. For Transwell experiments, CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells (106) plus allogeneic normal mDCs (105) were either added directly to the coculture of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (106) with allogeneic normal mDCs (105) or were separated in 24-well plates. Following depletion of DCs, T cells (105) were transferred to 96-well plates to measure the proliferative response on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs by Student paired t test. Error bars express SD of mean values.

Characterization of CD8+CD28− T cells generated from the primed human naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs.

(A) Human allogeneic naive CD8+ T cells (5 × 106) were cultured with allogeneic normal or regulatory DCs (5 × 105) for 5 days, and CD8+ T cells isolated from the coculture were assayed for phenotype (left panel) and cytokine profile (right panel) by FACS. The results are representative of 5 experiments with similar results; data are represented by a dot plot. (B) CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells were isolated from the coculture of human naive CD8+ T cells (5 × 106) with allogeneic normal mDCs or regulatory iDCs (5 × 106) for 5 days. Ag-primed CD4+ T cells, CD8+CD28+ T cells, or CD8+CD28− T cells (105) were cultured with or without allogeneic normal mDCs (104). In another experiment, Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (105) were cultured with allogeneic normal mDCs (104) in the presence or absence of different numbers of CD8+CD28+ T cells and CD8+CD28− T cells in 96-well plates, and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. For Transwell experiments, CD8+CD28+ T cells or CD8+CD28− T cells (106) plus allogeneic normal mDCs (105) were either added directly to the coculture of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (106) with allogeneic normal mDCs (105) or were separated in 24-well plates. Following depletion of DCs, T cells (105) were transferred to 96-well plates to measure the proliferative response on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SD of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells plus allogeneic normal mDCs by Student paired t test. Error bars express SD of mean values.

We also examined the effect of CD8+CD28− T cells generated from the primed naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory iDCs on the allogeneic response of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells (Figure 4B). CD8+CD28+T cells generated from the primed naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic normal mDCs showed a response to allogeneic normal mDCs. In contrast, CD8+CD28− T cells not only showed a poor response to allogeneic normal mDCs but also suppressed the response of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells to allogeneic normal mDCs in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, this suppressive effect was abrogated when the 2 cell populations were separated. We also observed that CD8+CD28+ T cells generated from the primed naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory iDCs showed a poor response to allogeneic normal mDCs, whereas they did not show the suppressive effect (data not shown). These results indicate that regulatory DCs could generate CD8+CD28− Tr cells from naive CD8+T cells.

Impairment of xenogeneic response of human T cells by murine regulatory DCs

There is increasing interest in xenogeneic organ transplantation in a clinical setting, and the suppression of human xenoreactive T cells is thought to be crucial for xenogeneic organ transplantation. To test whether regulatory DCs can regulate xenoreactive T cells, we generated modified DCs from murine BM cells (H-2d). In contrast to murine normal DCs, murine modified DCs showed moderately high expression levels of the DC marker (CD11c) and MHC molecules (I-Kd and I-A/I-E), whereas they exhibited extremely low levels of costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86; Figure5A). Furthermore, murine modified DCs showed poor activation of human T cells as compared with murine normal DCs (data not shown). In addition, the primed human T cells with murine normal DCs (H-2d) responded to restimulation with murine normal mDCs (H-2d), whereas the primed human T cells with murine modified DCs failed to respond to this stimulation (data not shown), indicating that murine modified DCs also act as regulatory DCs to induce an anergy in human xenoreactive T cells.

Murine regulatory DCs induce T-cell anergy in human xenoreactive T cells.

(A) Cells were stained with the stated mAbs or isotype-matched mAbs, and cell surface expression was analyzed by FACS. Data are represented by a histogram in which cells were stained with the stated mAbs (thick lines) or isotype-matched mAbs (thin lines). The values shown in the flow cytometry profiles are MFI. The results are representative of 5 individual experiments with similar results. (B) SCID mice received transplants of unprimed human T cells (●), human T cells primed with murine normal DCs (▴), human T cells primed with murine regulatory DCs (▪), or human T cells primed with murine regulatory DCs plus human IL-2 at a T cell/DC ratio of 10:1 for 3 days (▾). Mice were monitored daily for survival. The results are representative of 2 individual experiments with similar results. P < .01 compared with hu-PBL-SCID mice by the Mann-Whitney U test). (C) Human T cells were obtained from the spleen in each group of hu-PBL-SCID mice on day 10 after xenogeneic transplantation. Isolated human T cells (105) were cultured with murine normal DCs (103 to 5 × 104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SDs of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with human T cells plus murine normal DCs by Student pairedt test. (D) The hu-PBL-SCID mice were injected with or without murine regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse) 2 days following xenogeneic transplantation. Alternatively, intravenous injections of human IL-2 (104U/mouse) were performed on days 3, 5, and 7 following xenogeneic transplantation in hu-PBL-SCID mice receiving murine regulatory DCs. Mice were monitored daily for survival. The results are representative of 2 individual experiments with similar results. P < .01 compared with hu-PBL-SCID mice by the Mann-Whitney U test. (E) SCID mice received transplants of murine allogeneic BM cells plus spleen mononuclear cells. Subsequently, the recipients were injected with or without murine normal or regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse) 2 days following allogeneic transplantation. Mice were monitored daily for survival. The results are representative of 2 individual experiments with similar results. P < .01 compared with untreated SCID mice that did not receive transplants by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Murine regulatory DCs induce T-cell anergy in human xenoreactive T cells.

(A) Cells were stained with the stated mAbs or isotype-matched mAbs, and cell surface expression was analyzed by FACS. Data are represented by a histogram in which cells were stained with the stated mAbs (thick lines) or isotype-matched mAbs (thin lines). The values shown in the flow cytometry profiles are MFI. The results are representative of 5 individual experiments with similar results. (B) SCID mice received transplants of unprimed human T cells (●), human T cells primed with murine normal DCs (▴), human T cells primed with murine regulatory DCs (▪), or human T cells primed with murine regulatory DCs plus human IL-2 at a T cell/DC ratio of 10:1 for 3 days (▾). Mice were monitored daily for survival. The results are representative of 2 individual experiments with similar results. P < .01 compared with hu-PBL-SCID mice by the Mann-Whitney U test). (C) Human T cells were obtained from the spleen in each group of hu-PBL-SCID mice on day 10 after xenogeneic transplantation. Isolated human T cells (105) were cultured with murine normal DCs (103 to 5 × 104), and the proliferative response was measured on day 5. Data were expressed as mean values ± SDs of 5 individual experiments. *P < .01 compared with human T cells plus murine normal DCs by Student pairedt test. (D) The hu-PBL-SCID mice were injected with or without murine regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse) 2 days following xenogeneic transplantation. Alternatively, intravenous injections of human IL-2 (104U/mouse) were performed on days 3, 5, and 7 following xenogeneic transplantation in hu-PBL-SCID mice receiving murine regulatory DCs. Mice were monitored daily for survival. The results are representative of 2 individual experiments with similar results. P < .01 compared with hu-PBL-SCID mice by the Mann-Whitney U test. (E) SCID mice received transplants of murine allogeneic BM cells plus spleen mononuclear cells. Subsequently, the recipients were injected with or without murine normal or regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse) 2 days following allogeneic transplantation. Mice were monitored daily for survival. The results are representative of 2 individual experiments with similar results. P < .01 compared with untreated SCID mice that did not receive transplants by the Mann-Whitney U test.

The preventive effect of a group of DCs on T cell–mediated immunopathogenic diseases via an induction of T-cell anergy remains unknown. The hu-PBL-SCID mice (H-2d) reportedly showed a lethal XGVHD, and the depletion of human CD4+ T cells abrogated this pathogenesis.10 To evaluate the inhibitory effect of regulatory DCs on T cell–mediated immunopathogenesis in vivo, we examined the ability of the primed human T cells with murine regulatory DCs to induce XGVHD in hu-PBL-SCID mice (Figure 5B). All hu-PBL-SCID mice (control group) died of XGVHD within 24 days following transplantation. In these mice, clinical symptoms of XGVHD, such as hair ruffling, lower mobility, and weight loss became apparent within 15 days. Transplantation with the primed human T cells with murine normal DCs enhanced the incidence of XGVHD, and this treatment reduced the life span of these engrafted mice as compared with the control group (P < .01). In contrast, the incidence of XGVHD was significantly reduced in SCID mice receiving transplants of the primed human T cells with murine regulatory DCs compared with the control group (P < .01). In addition, the survival period was significantly reduced when SCID mice received transplants of the primed human T cells with murine regulatory DCs in the presence of human IL-2 (P < .01).

We also examined the xenogeneic response of the transplanted human T cells obtained from the spleen in hu-PBL-SCID mice 10 days following xenogeneic transplantation against murine normal DCs (H-2d; Figure 5C). Analysis of the spleen in each group of hu-PBL-SCID mice showed that they were consistently engrafted with approximately 80% of human T cells at 10 days after xenogeneic transplantation. The xenogeneic response of the transplanted human T cells obtained from SCID mice receiving transplants of the primed human T cells with murine normal DCs was higher than that of human T cells obtained from hu-PBL-SCID mice. In contrast, the transplanted human T cells obtained from SCID mice transplanted with the primed human T cells with murine regulatory DCs had a poor xenogeneic response to murine normal DCs.

We further examined the therapeutic effect of a single injection with murine regulatory DCs following xenogeneic transplantation on the lethality caused by XGVHD in hu-PBL-SCID mice (Figure 5D). A single injection with murine regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse) following xenogeneic transplantation had no effect on the engraftment of human T cells in spleen in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Interestingly, this injection prolonged the life span of hu-PBL-SCID mice compared with the control group (P < .01), whereas a single injection of the lower dose (< 4 × 105/mouse) of murine regulatory DCs failed to exhibit a significant therapeutic effect (data not shown). We also observed that the sequential injections of human IL-2 abrogated their therapeutic effect. Similarly, a single injection with murine regulatory DCs (4 × 106/mouse), but not murine normal DCs (4 × 106/mouse), following allogeneic transplantation showed a therapeutic effect on the lethality caused by allogeneic acute GVHD (Figure 5E).

Discussion

Although DCs reportedly act as natural adjuvants to induce protective immunity against cancer and infectious diseases in humans, the strategy of the DC-mediated negative regulation of the T-cell response has not been established. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to report that a group of human and murine DCs retain the potent immunoregulatory property in vitro and in vivo even under inflammatory conditions and show a protective effect on immunopathogenic disease.

We showed that the inflammatory stimulation failed to elicit a fully immunostimulatory maturational change in human regulatory iDCs, whereas the maturation-associated change in several cell surface molecules was observed. Therefore, the maturational process may be selectively impaired in human regulatory DCs.

Analysis of phenotype and function of normal DCs suggest that they could efficiently deliver potent signals to T-cell receptor for Ag (TCR) ligands (signal 1) and to costimulatory molecules (signal 2)1,17 in alloreactive CD4+ T cells. In contrast, IL-10–treated iDCs3,4 and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-treated iDCs18reportedly induced anergic CD4+ T cells in human in vitro. Furthermore, repetitive stimulation of human naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic normal iDCs also generated anergic CD4+ T cells.5 We showed that regulatory DCs exhibited moderately high levels of MHC molecules, whereas they exhibited little expression of costimulatory molecules as compared with their normal counterparts. Furthermore, regulatory DCs showed lower activation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells in the priming and more potent induction of their anergic state on restimulation with same donor-derived normal mDCs than IL-10–induced iDCs. These phenomena imply that the condition responsible for the induction of T-cell anergy by tolerant DCs is that the degree of T-cell activation in the priming is much lower than that on restimulation. Collectively, the characteristic expression profile of MHC and costimulatory molecules in regulatory DCs is associated with their potent ability to induce anergy, by which they may deliver potent signal 1 plus poor signal 2 to alloreactive CD4+ T cells.

We showed that priming with allogeneic normal mDCs enhanced the cytolytic activity of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells in an Ag-dependent manner. Therefore, allogeneic normal mDCs may activate these CD8+ T cells mediated through the delivery of potent signal 1 plus signal 2. On the other hand, the primed allogeneic Ag-specific CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs had reduced their activity in an Ag-dependent manner. Our results suggest that regulatory DCs deliver potent signal 1 plus poor signal 2 to Ag-specific CD8+ T cells, and that results in the induction of their anergic state.

Serial stimulations were needed for allogeneic normal iDCs to induce CD4+CD25+ Tr cells from naive CD4+T cells.5 On the other hand, we have recently reported that a single stimulation with IL-10–induced semimature DCs could induce CD4+CD25+ Tr cells from the unprimed CD4+ T cells.4 We showed that a single stimulation with allogeneic regulatory DCs was sufficient for the efficient generation of CD4+CD25+ Tr cells from naive CD4+ T cells, indicating that regulatory DCs had a much more potent ability to induce CD4+CD25+ Tr cells as compared with normal iDCs and IL-10–induced semimature DCs. On the other hand, the mechanism responsible for the generation of CD4+ CD25+ Tr cells from the primed naive CD4+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs remains unknown. Our results imply that allogeneic regulatory DCs may convert naive CD4+ T cells into CD4+CD25+ Tr cells. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that minimal numbers of CD4+CD25+ T cells were included in cocultures. It is possible that allogeneic regulatory DCs may preferentially expand naturally existing CD4+CD25+ T cells. Further study will be needed to test these possibilities.

The allogeneic regulatory DC-induced anergic state in CD4+T cells was partly restored by IL-2. CD4+CD25+Tr cells were reportedly unresponsive to IL-2.19 Thus, this mechanism may involve the existence of CD4+CD25+ Tr cells. On the other hand, allogeneic regulatory DC-induced CD4+CD25+ Tr cells caused the allogeneic Ag-specific and -nonspecific inhibitory effects. CD4+CD25+ Tr cells are known to suppress the response of CD4+ T cells in an Ag-nonspecific manner.5,13,19 However, recent studies have shown the Ag-specific suppression of CD4+CD25+ Tr cells in humans and animals.20 21 Analysis of Ag specificity of the inhibitory effect of CD4+CD25+ Tr cells showed that they exhibited both Ag-specific and Ag-nonspecific suppressive effects. These phenomena imply that the heterogeneity of allogeneic regulatory DC-induced CD4+CD25+ Tr cells may reflect the requirement of Ag specificity for their effector function.

In contrast to IFN-γ–producing CD8+CD28− Tr cells14-16 or IL-10–producing CD8+ T cells,6 CD8+CD28− Tr cells generated from the primed naive CD8+ T cells with allogeneic regulatory DCs suppressed the activation of Ag-primed CD4+ T cells, and they could produce IL-10. It has been suggested that CD8+CD28− Tr cells represent a distinct subset in a heterogeneous population.15 These phenomena imply that the different types of allogeneic/xenogeneic APCs may regulate the development of naive CD8+ T cells into the distinct subsets of CD8+CD28− Tr cells.

The mechanism by which CD4+CD25+ Tr and CD8+CD28− Tr cells exerted an inhibitory effect remains unclear although the mechanism of their action has been debated.12 13

Consistent with previous reports,5,12,16 our results indicate that direct cell contact of these Tr cells with Ag-primed CD4+ T cells, but not soluble factors secreted from these Tr cells, appears to be essential for their suppressive capacity. Our results imply that the suppressive effect of these Tr cells may not be due to simple competition for APCs or IL-2. CD4+CD25+ Tr cells reportedly blocked the induction of IL-2 production by CD4+CD25− T cells at the level of RNA transcription, and activation apparently enhanced the immunosuppressive function of these cells.19On the other hand, stimulation through the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family-related gene abrogated the suppressive effects of CD4+CD25+ Tr cells.22 Further study will be needed to clarify the mechanism responsible for their inhibitory effect.

We showed that hu-PBL-SCID mice succumbed to XGVHD, and the transplanted human T cells obtained from hu-PBL-SCID mice responded to murine normal DCs. Therefore, this xenogeneic response is likely to be mediated through a direct recognition of murine H-2d MHC molecule of SCID mice by human T cells. Furthermore, in vitro priming with murine normal DCs not only enhanced xenogeneic response of human T cells to murine normal DCs but also promoted the lethality caused by XGVHD. These findings suggest that the priming with murine normal DCs up-regulates the ability of human T cells to cause a xenoreactive response.

In vitro priming with murine regulatory DCs impaired the ability of human T cells to respond to further stimulation with murine normal DCs as well as to induce XGVHD in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Analysis of SCID mice transplanted with the primed human T cells with murine regulatory DCs revealed that the transplanted human T cells retained an anergic state in vivo. In addition, a single injection with murine regulatory DCs following xenogeneic transplantation caused the therapeutic effect on the lethality caused by XGVHD in hu-PBL-SCID. On the other hand, these protected mice showed similar engraftment of human T cells to that of the control group, indicating that their protective effect may not be due to the failure of their engraftment mediated through the rejection/lysis of the human cells. Interestingly, host APCs reportedly play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of allogeneic acute GVHD, and their inactivation led to the prevention of allogeneic acute GVHD in the murine model.23 Indeed, we showed that murine regulatory DCs also showed a protective effect on allogeneic acute GVHD. Therefore, our finding suggests that murine regulatory DCs could induce an anergic state in human xenoreactive T cells and murine alloreactive T cells, and that led to the protection of the recipients from the lethality caused by XGVHD as well as allogeneic acute GVHD. We also observed that in vitro or in vivo treatment with human IL-2 abrogated the protective effect of murine regulatory DCs on XGVHD in hu-PBL-SCID mice, and it is possibly mediated through the restoration of xenoreactivity of the transplanted human T cells.

In summary, regulatory DCs were potent regulators for T cell–mediated immunity in vivo and in vitro, and these cells retained their immunoregulatory property even once matured. Therefore, the strategy with self-Ag (peptides or protein)–pulsed autologous or allogeneic/xenogeneic regulatory DCs in humans may be useful for the prevention and the treatment of inflammation, autoimmune diseases, and allogeneic/xenogeneic organ transplantation. To test our hypothesis, preclinical studies with regulatory DCs in animal immunopathogenic models are being conducted in our laboratories.

We thank Dr Kaori Denda-Nagai for helpful advice on the preparation of murine normal DCs and Mai Yamamoto for her excellent assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 2, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2712.

Supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (13218027), the Naito Foundation, Nagao Memorial Fund, Japan Rheumatism Foundation, and Kodama Memorial Fund Medical Research (K.S.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Katsuaki Sato, Department of Immunology and Medical Zoology, School of Medicine, Kagoshima University, 8-35-1 Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima 890-8520, Japan; e-mail: katsuaki@m3.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.