Abstract

There were 26 patients enrolled in a pilot study of high-dose immunosuppressive therapy (HDIT) for severe multiple sclerosis (MS). Median baseline expanded disability status scale (EDSS) was 7.0 (range, 5.0-8.0). HDIT consisted of total body irradiation, cyclophosphamide, and antithymocyte globulin (ATG) and was followed by transplantation of autologous, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized CD34-selected stem cells. Regimen-related toxicities were mild. Because of bladder dysfunction, there were 8 infectious events of the lower urinary tract. One patient died from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) associated with a change from horse-derived to rabbit-derived ATG in the HDIT regimen. An engraftment syndrome characterized by noninfectious fever with or without rash developed in 13 of the first 18 patients and was associated in some cases with transient worsening of neurologic symptoms. There were 2 significant adverse neurologic events that occurred, including a flare of MS during mobilization and an episode of irreversible neurologic deterioration after HDIT associated with fever. With a median follow-up of 24 (range, 3-36) months, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of progression (≥ 1.0 point EDSS) at 3 years was 27%. Of 12 patients who had oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid at baseline, 9 had persistence after HDIT. After HDIT, 4 patients developed new enhancing lesions on magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. The estimate of survival at 3 years was 91%. Important clinical issues in the use of HDIT and stem cell transplantation for MS were identified; however, modifications of the initial approaches appear to reduce treatment risks. This was a heterogeneous high-risk group, and a phase 3 study is planned to fully assess efficacy. (Blood. 2003;102:2364-2372)

Introduction

The major histologic features of the lesions in the central nervous system (CNS) of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are inflammation, demyelination, and gliosis. A prominent inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes and monocytes) occurs in the perivascular space as well as in the plaques and normally myelinated CNS. Although the etiology for the progressive neurologic loss is not fully defined, evidence points to an autoimmune pathogenesis in the initial stages. In the more aggressive forms of MS, a profound disability can result, and in some cases life expectancy can be significantly shortened.1-3 In a recent study of the natural history of MS, the median time from the onset of MS to a Kurzke expanded disability status scale (EDSS) score of 7.0 (ability to walk with bilateral support no more than 10 meters [m] without rest) was 29.9 years.4,5 However, the median times from the assignment of an EDSS score of 4.0 (limited walking ability but walks without aid for > 500 m) to a score of 6.0 (ability to walk with unilateral support no more than 100 m) and a score of 6.0 to 7.0 were 5.7 and 3.4 years, respectively. At 30 to 40 years after onset of the progressive phase of the disease, up to 80% of patients had an EDSS of 8.0 points (restricted to bed or chair with support) or greater.6 None of the current treatments using immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory agents are curative, although a decrease in the frequency of relapse and delay in loss of neurologic function has been demonstrated.7-11 To date, no effective therapy has been reported for primary progressive (PP) MS.

Studies of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), a murine model for MS, have indicated that disease control can be obtained by high-dose immunosuppressive therapy (HDIT) followed by transplantation with allogeneic, syngeneic, and autologous marrow.12-15 Previous clinical experience with allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplantations (SCTs) suggested that long-term remissions could be achieved in otherwise incurable autoimmune diseases.16-18 The underlying hypothesis for this study was that HDIT followed by infusion of lymphocyte-depleted (CD34-selected) autologous peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) would allow near ablation of autoreactive immune effector cells preventing further loss of neurologic function. This would be followed by regeneration of a self-tolerant immune system from T-cell-depleted multipotential hematopoietic progenitors. Accordingly, a pilot study was performed of HDIT followed by hematopoietic rescue with the infusion of autologous CD34-selected PBSCs to obtain safety and preliminary efficacy data in patients with severe MS.

Patients, materials, and methods

Study design and patients

From July 1998 to April 2001, 26 patients were registered on the multicenter study coordinated by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC). Patients were enrolled at FHCRC (n = 17), University of Nebraska (n = 4), Washington University (n = 2), University of Colorado (n = 1), City of Hope (n = 1), and Texas Transplant Institute (n = 1). Patients who were included had clinically definite or laboratory-supported definite MS by Poser criteria and a PP, secondary progressive (SP), or relapsing-remitting (RR) disease course. To be eligible, patients with RR MS had to have 2 or more attacks in the previous 2 years. The EDSS (0 = normal, 10 = death due to MS) was required to be between 5.0 and 8.0 inclusive, with a worsening in EDSS of 1.0 or more points over the previous year. All patients were examined and approved by 2 neurologists to confirm eligibility. The primary objective of the pilot study was to assess the safety of the HDIT regimen and the transplantation of autologous CD34-selected stem cells. Secondary end points included disease response, safety of mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and immunologic recovery. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at FHCRC and the collaborating centers. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were not eligible for the study if they had significant end organ dysfunction that precluded the safe use of HDIT.

Treatment and supportive care

PBSCs were mobilized in the outpatient department with subcutaneous G-CSF at 16 μg/kg per day. The first apheresis was done on day 4. G-CSF-mobilized PBSC products were CD34-selected19 using an Isolex 300I (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) with targets of more than 3.5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg. Unmodified PBSCs (> 3.0 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg) were also stored for potential back-up use. The autologous cell product was evaluated after CD34 selection for content of CD34+ cells and T cells (CD3+)by flow cytometry. Cells were cryopreserved using standard techniques.20 Because of a flare of MS during mobilization of the fourth patient, routine administration of prednisone was started with the fifth patient enrolled in the study. Prednisone (1 mg/kg per day) was administered 1 day before the start of G-CSF and continued for 10 days.

HDIT included fractionated total body irradiation (TBI) delivered as 200 cGy fractions, 2 fractions per day, on day -5 and day -4, for a total dose of 800 cGy; cyclophosphamide (Cy; 60 mg/kg intravenously) on each of days -3 and -2; and equine antithymocyte globulin (ATG [15 mg/kg per day intravenously]; ATGAM; Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ) on days -5, -3, -1, +1, +3, and +5. Day 0 was designated as the day of PBSC infusion. Methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg intravenously) was given with each dose of ATG. Individual TBI treatments were delivered with a minimum of 5 hours between fractions. TBI was administered from either opposing dual 60Cobalt sources or linear accelerators at dose rates of 7 to 15 cGy per minute. TBI from the dual opposed 60Cobalt sources was administered without lung shielding, which was not required because of the patient positioning in the radiation field. If TBI was administered from a linear accelerator, lung shielding was used to limit whole lung doses to approximately 650 cGy. This was accomplished by the use of a partial transmission block. G-CSF (5 μg/kg per day intravenously) was given from day 0 until the absolute neutrophil count was higher than .5 × 109/L (500/μL) for 3 days. The engraftment syndrome occurred more frequently than expected in the first 18 patients of the study, and in some of these patients, it was associated with neurologic complications. To prevent the engraftment syndrome from developing, the final 8 patients of the study were given a short course of prednisone after transplantation. Prednisone (0.5 mg/kg per day) was given as a single dose from day +7 to day +21 and then was tapered and completed at day +30 to prevent neurologic complications during engraftment. Patients were hospitalized from the start of conditioning therapy until there was neutrophil engraftment and resolution of major toxicities. Infection prophylaxis included trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for Pneumocystis carinii (given for 1 year),21 fluconazole for Candida (75 days),22 and acyclovir for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (1 year). Monitoring for cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation continued until one year after HDIT and if positive treatment with ganciclovir was started.23

Evaluation of outcome

Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first of 2 consecutive days with neutrophil counts .5 × 109/L (500/μL) or higher and platelet engraftment the first of 3 consecutive days with platelet counts 20 × 109/L (20 000/μL) or higher without transfusions. Regimen-related toxicities were defined according to the Bearman scale as those occurring within 28 days after transplantation.24 Engraftment syndrome was characterized by the development of a fever (> 38.3°C) with or without a rash occurring near the time of engraftment in the absence of infection.

Disease status evaluations were performed before mobilization (baseline) with G-CSF and at 1, 3, 12, 24, and 36 months after HDIT. Studies before mobilization contributed to the confirmation of the diagnosis and status of MS as well as a baseline comparison for assessing changes over time. Studies included a formal clinical evaluation, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with and without gadolinium infusion. The clinical assessment included scoring for the 9-hole peg test,25 the EDSS,26 and the Scripps neurologic rating scale (NRS).27 Treatment failure was defined as disease progression from the pre-HDIT EDSS of 1.0 or more points beyond 3 months after HDIT with no other explanation of change in function. The time of the first increase to 1.0 or more EDSS points was taken as the time to disease progression. Evaluations at 1 and 3 months were done to assess for adverse neurologic events of the procedure. The goal of therapy was to prevent disease progression and further loss of neurologic function. The CSF examination assessed the presence of oligoclonal bands, a potential surrogate marker for the inflammatory process in the central nervous system.

MRI of the brain

Patients had scheduled MRI scans of the brain at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after HDIT. MRI scans of the brain from all patients at baseline and at last follow-up after HDIT were centrally reviewed by a blinded single neuroradiologist and qualitatively assessed for development of new or expanding lesions on the T2 weighted images and for the presence of new gadolinium-enhancing lesions. Scan pairs for each patient were displayed with the dates of each examination blanked out, and the chronologic order of the scans was randomized. Scan pairs were assessed for possible change in T2 lesion burden and for the presence or absence of enhancing lesions at each of the 2 time points analyzed. The T2 lesion burden was scored on a scale from normal (no abnormalities detected) to severe (Table 4). The clinical impressions (unblinded) of MRI scans of the brain by neuroradiologists at all the study centers were also recorded.

A subset of patients treated at FHCRC/University of Washington (UW) had MRI scans of the brain obtained on 1.5T MRI scanners for a quantitative analysis of the volume of T2 lesion burden and for total brain volume. Scans were obtained using 3-mm slice thickness and no interslice gap. Images for each MRI study were carefully angled parallel with the anterior commissure-posterior commissure line so that each scan session was directly comparable with all previous studies on the same patients. Images for each study in axial plane were obtained using T1, spin density, T2, and FLAIR pulse sequences before gadolinium injection. A T1 weighted set of axial images was also obtained following gadolinium injection. Of the 17 patients in this group, 5 did not return to FHCRC/UW for MRI scans at one year and were not evaluable because of loss of follow-up (lack of medical insurance or patient refusal) or death.

MRI scans were analyzed at baseline and at one year of follow-up; thus, all patients had the same follow-up times. A single, experienced neuroradiologist (M.P.) performed all of the quantitative analyses. Images were analyzed using iQuantify (Insightful, Seattle, WA). This program used proton density and T2 weighted images to characterize the slope of signal intensity change on a pixel-by-pixel basis. By adjusting the threshold one could then separate tissues with different characteristic slopes of signal intensity change. Images were analyzed using a 2-step semiautomated interactive process. First, the threshold was adjusted to highlight most pixels with hyperintense T2 signal characteristic of MS plaques. Then, overlaying the identified pixels on the proton density image, the investigator highlighted any additional pixels of T2 signal change that were not identified on the automated selection. The program then calculated a total T2 lesion volume for the whole brain.

Immune recovery

Lymphocyte subsets were enumerated using 3-color flow cytometry as described.28-31 Briefly, blood mononuclear cells (MNCs) were stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluorochromes (fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin, phycoerythrin + cyanin 5). Flow cytometry data were acquired using FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and analyzed using Winlist software (Verity, Topsham, ME). CD4 T cells were defined as CD3+CD4+CD8- MNCs. CD8 T cells were defined as CD3+CD4-CD8+ MNCs. B cells were defined as MNCs expressing CD19 or CD20 and not brightly expressing CD3, CD10, CD13, CD14, CD16, CD34, or CD56. Natural killer (NK) cells were defined as MNCs expressing CD16 or CD56 and not expressing CD3 or CD14. Absolute counts (per unit volume) were calculated as percentages (determined by flow cytometry) multiplied by absolute lymphocyte + monocyte counts (determined by clinical hematology laboratory) and divided by 100.

Statistics

Outcomes are reported as of July 2002 and are based on the last follow-up of each patient. Medians and ranges are reported unless otherwise specified. Since this was a pilot study, safety and efficacy end points including treatment failure were reported in a descriptive analysis. Changes in EDSS and Scripps scores from baseline were estimated, and 95% confidence limits for the estimated change in Scripps score were provided at various time points. Overall survival and survival were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier (KM), and disease progression was summarized using a cumulative incidence estimate (KM).32,33

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the pretransplantation characteristics of the 26 patients enrolled in the study; 12 patients were female. Of the patients, 8 had PP MS, 17 had SP MS, and 1 had RR MS. The median age of the patient population was 41 (range, 27-60) years. The median duration of disease was 84 (range, 10-277) months, and the baseline median EDSS was 7.0 (range, 5.0-8.0). There were 7 patients who had gadolinium-enhancing lesions noted on the baseline MRI studies of the brain. Median follow-up for safety-related and efficacy-related end points is 28 (range, 3-47) and 24 (range, 3-36) months, respectively.

PBSC collections and engraftment

The median number of aphereses required for collection of the required number of CD34+ cells for SCT was 3.2-8 The median number of CD34-selected cells infused on day 0 was 4.1 (range, 3.3-8.2) × 106/kg. The median purity of the CD34-selected cell product was 84% (range, 54%-99%). T-cell content in the autologous graft after CD34 selection was 4.0 (range, 1.1-13.2) × 104 CD3+ cells/kg. The median time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was 9 (range, 6-13) and 9 (range, 6-16) days, respectively.

Infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) occurred in 8 patients. UTIs were more frequent in this population after HDIT than typically seen because of bladder dysfunction secondary to MS, which required indwelling urinary catheters or intermittent catheterization in 7 patients. Bacteremias occurred in 4 patients, and an infection of the exit site of the central venous catheter occurred in 1 patient. There were no serious outcomes from these bacterial infections. One patient developed a parainfluenza 3 infection of the upper respiratory tract, and one patient developed a rotavirus infection associated with diarrhea in the first 3 months after transplantation, both of which resolved. Late after transplantation, HSV infections occurred in 1 patient and varicella-zoster infections occurred in 2 patients; the infections resolved without sequelae after treatment. No fungal infections occurred.

Reactivations of CMV occurred in 4 of 9 seropositive patients. Of these patients, 3 had CMV antigenemia with no disease and were treated effectively with ganciclovir. The fourth patient with CMV antigenemia had received rabbit ATG in the HDIT regimen because of a positive skin test to the horse ATG. This patient developed CMV pneumonitis and gastroenteritis on day 14, which was treated with ganciclovir, cidofovir, and CMV immunoglobulin. The CMV pneumonitis was resolving satisfactorily on treatment, but on day 49 the patient presented with bilateral lung infiltrates and cervical lymphadenopathy. A diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) was confirmed by a lymph node biopsy, and rituximab was started on day 50. The patient died on day 53 from progressive EBV-PTLD. T cells in the peripheral blood were undetectable at day 28 after HDIT in contrast to all but one other patient in the study who received a partial course of rabbit ATG.

Regimen-related toxicities and other noninfectious adverse effects

During mobilization of PBSCs, patient no. 4 had a flare of MS associated with an increase of EDSS from a baseline of 7.0 to 8.0. Symptoms of the flare were noted in the first 24 hours after administration of the G-CSF. The MRI of the brain at one month after transplantation had new gadolinium-enhancing lesions. The patient had complete neurologic recovery to baseline by 6 months after HDIT, and at 2 years had a confirmed EDSS of 6.5 with no further relapses. Based on this experience and the reported experiences of other groups,34 the subsequent 22 patients received G-CSF for mobilization in combination with prednisone without any further episodes of flares.

An engraftment syndrome, consisting of fever with or without skin rash, developed in 13 of the first 18 patients of the study at a median of 12 (range, 7-16) days after HDIT. In most cases the fever was mild, transient, and associated with an increase of weakness. For skin rash or for persistent fever, 6 patients were treated with a short course of prednisone. The weakness resolved with the resolution of the fever in all but one patient. Patient no. 16 had development of high fever and skin rash that persisted for more than 14 days. No infectious source was identified. The patient progressed from an EDSS of 7.5 at baseline to 8.5 points at 12 months. After 12 months, there was further loss of neurologic function by history, and at 23 months after HDIT the patient died from aspiration pneumonia. MRI studies of the brain and the spinal cord did not show any changes compared with baseline studies. The final 8 patients of the study received prednisone from day 7 to day 30 after transplantation without the development of the engraftment syndrome.

High-dose immunosuppressive therapy was well tolerated by most patients. Mucositis was mild (grades 0-2), and other early regimen-related toxicities were grade 2 or less. Other complications noted were brachial neuritis in patient no. 15 and transient idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in patient no. 11 at 1 and 2 months after HDIT, respectively. Treated with prednisone were 2 patients who developed lymphocytic gastritis (pseudo graft-versus-host disease of the gastrointestinal tract). No long-term toxicities attributed to TBI have been noted except for patient no. 13 who was diagnosed with hypothyroidism at one year after HDIT. No secondary malignancies have occurred. The KM estimate of survival at 3 years was 91% (Figure 1).

Survival and progression after HDIT. Estimated survival was 91% and treatment failure was 27% at 3 years. Tick marks represent censored observations.

Survival and progression after HDIT. Estimated survival was 91% and treatment failure was 27% at 3 years. Tick marks represent censored observations.

Evaluation of disease response

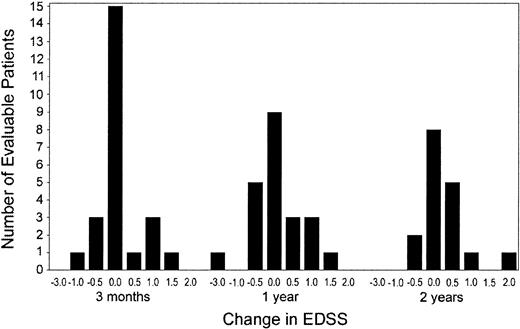

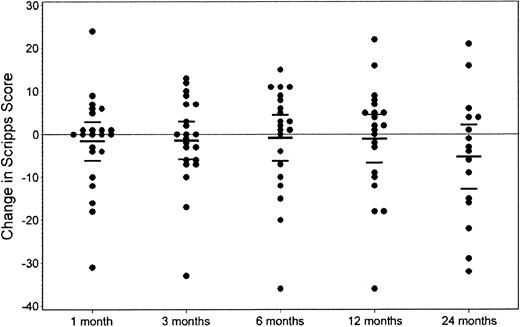

Clinical assessment. Of the 25 evaluable patients with a median follow-up of 24 (range, 3-36) months, 6 patients (24%) experienced treatment failure (increase in EDSS of > 1.0 point), 1 of which was related to a sustained fever secondary to the engraftment syndrome after HDIT (Table 2). An additional 3 patients had unconfirmed increases of 0.5 point (EDSS), 2 had decreases of 0.5 point, and 14 patients remained stable at last follow-up (Figure 2; Table 2). Disease stabilization was observed in both PP and SP MS, and the one patient with RR MS was improved (Table 3). The KM estimate of progression of 1.0 or more EDSS points was 27% (Figure 1). Analysis, using the broader 100-point Scripps neurologic rating scale in patients with a minimum follow-up of one year (n = 23), showed no significant change in the score when compared with their baseline function (Figure 3). There were 21 patients evaluable for the 9-hole peg test with a median follow-up of 12 (range, 1-36) months. Of the patients, 1 improved, 13 remained stable, and 7 became worse.

Neurologic status after HDIT: change in EDSS. Distribution of the changes in EDSS scores compared with baseline at 3, 12, and 24 months after HDIT.

Neurologic status after HDIT: change in EDSS. Distribution of the changes in EDSS scores compared with baseline at 3, 12, and 24 months after HDIT.

Neurologic status after HDIT: change in Scripps score. Dot plot of the changes in Scripps score compared with baseline at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. There was no change evident in the mean Scripps score 2 years after HDIT. Center bar indicates the mean of the changes in Scripps score. Top and bottom bars are the 95% confidence limits.

Neurologic status after HDIT: change in Scripps score. Dot plot of the changes in Scripps score compared with baseline at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. There was no change evident in the mean Scripps score 2 years after HDIT. Center bar indicates the mean of the changes in Scripps score. Top and bottom bars are the 95% confidence limits.

Assessment of MRI imaging. There were 25 evaluable patients who had MRI scans at a median of 24 (range, 1-24) months after treatment (Table 4). Based on the unblinded evaluations of all MRI scans done after HDIT, new or enhancing lesions were noted in 4 patients, including those observed in patient no. 4 on day 28 associated with the flare of MS during mobilization. Patient no. 6 had one new enhancing lesion at month 12, patient no. 12 had enhancing lesions until month 6, and patient no. 24 had persistent lesions until the last scheduled MRI of the brain at 12 months after HDIT. In a blinded comparison of baseline and last MRI scans of the brain performed in the study by a central reviewer, there were no apparent increases in T2 burden except for a slight increase in one patient. In a subset of 12 patients who had imaging studies done serially at the University of Washington (“Patients, materials, and methods”), a quantitative analysis was done of the T2 weighted images to assess changes in burden of disease and brain volume over the first year after HDIT. Lesion volume was decreased by a median of -6.6% (range, -22.7% to 34.6%). Total brain volume decreased by a median of -1.84% (range, -7.39% to +4.47%).

Assessment of CSF. In 20 evaluable patients, oligoclonal bands were present in the CSF of 12 patients before HDIT. At last follow-up, 9 patients had persistence of the oligoclonal bands in the CSF after HDIT (Table 2). Of the 8 patients with no evidence of oligoclonal bands at baseline, one patient became positive after HDIT.

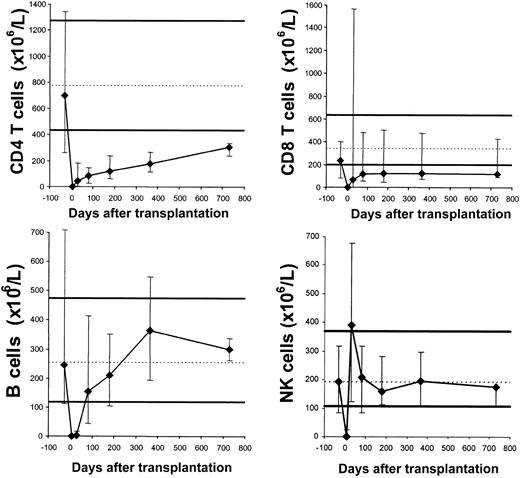

Immune reconstitution

The transplantation induced profound lymphocytopenia. Recovery to normal values was the fastest for NK cells, intermediate for B cells, and the slowest for T cells (Figure 4).

Recovery of lymphocyte subsets. Median subset counts in the patients before transplantation (prior to G-CSF mobilization, arbitrarily displayed as day -30) and approximately on days 7, 30, 80, 180, 365, and 730. Error bars denote the 10th to 90th percentiles. Reference values are indicated by the solid thick lines that represent the 10th to 90th percentiles and the broken thin lines that represent the medians of 104 healthy adults. The numbers of patients studied were 22 before transplantation, 23 on day 7, 22 on day 30, 20 on day 80, 19 on day 180, 13 on day 365, and 3 on day 730.

Recovery of lymphocyte subsets. Median subset counts in the patients before transplantation (prior to G-CSF mobilization, arbitrarily displayed as day -30) and approximately on days 7, 30, 80, 180, 365, and 730. Error bars denote the 10th to 90th percentiles. Reference values are indicated by the solid thick lines that represent the 10th to 90th percentiles and the broken thin lines that represent the medians of 104 healthy adults. The numbers of patients studied were 22 before transplantation, 23 on day 7, 22 on day 30, 20 on day 80, 19 on day 180, 13 on day 365, and 3 on day 730.

Discussion

The use of intensive chemoradiotherapy with stem cell rescue offers an opportunity to deliver maximally tolerated immunosuppression. This conceptual approach is similar to that used in autografting for lymphoma in which patients who have failed conventional chemotherapy regimens may respond to high-dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous SCT. Although the pathogenesis of MS is not fully understood, and lymphoid effector cells are not well defined, evidence implicates a role for autoreactive T and B lymphocytes. If these effectors could be eradicated or severely depleted by HDIT, sustained disease remissions may be induced. In the EAE mouse model, immunoablation with TBI followed by allogeneic, syngeneic, or autologous marrow rescue can prevent or ameliorate clinical disease.14,15,35,36 The goal of HDIT in this clinical study was to achieve sustained remissions of the autoimmune process and prevent further loss of neurologic function.

During the initial phases of the study, one patient developed a flare of MS during the administration of only G-CSF for the mobilization. This experience was previously reported along with several other cases.37 G-CSF has previously been associated with flares of autoimmune diseases during treatment for neutropenia or mobilization before HDIT.38-42 Although mobilization with G-CSF is associated with a type 2, anti-inflammatory cytokine profile, the clinical relevance of this observation even for the development of alloimmune reactions after hematopoietic SCT are unclear.43 The addition of a 10-day course of prednisone administered during mobilization appears effective in reducing the risk of MS flares, but more experience is required to increase confidence in this strategy. The addition of cyclophosphamide to G-CSF during mobilization has also been effective for preventing flares. However, the disadvantage of combining cyclophosphamide with G-CSF during mobilization is the increased risk to the patient due to an additional pancytopenic interval, the increased cost of management of patients receiving chemotherapy, and the delay in proceeding to HDIT. Mobilization using G-CSF with prednisone has been safe and effective and may prove to be the preferred approach in MS patients.

In preclinical studies of HDIT for autoimmune diseases, TBI was a more effective immunosuppressive treatment than chemotherapeutic regimens.44 The TBI dose described in this current study was decreased from a more standard dose (1200 cGy) used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies so as to minimize the risks of severe regimen-related toxicities. Autologous stem cell support is required after HDIT because fractionated TBI doses to a total of 800 cGy in combination with high-dose cyclophosphamide are extremely myelosuppressive if not myeloablative.45 A noncytotoxic agent, ATG, was added to the HDIT regimen for in vivo T-cell depletion. Cyclophosphamide in combination with TBI has potent immunosuppressive capabilities and is one of the most common conditioning regimens for allogeneic SCT. The potential efficacy of this HDIT regimen has been demonstrated in another study coordinated by this program in which patients with systemic sclerosis had a significant reduction in the extent of the scleroderma compared with the pretransplantation baseline.46 The combination of TBI and cyclophosphamide at the dose delivered in that study was not associated with severe regimen-related or neurologic toxicities. Patients have not been followed for a sufficient time period to allow for full assessment of long-term complications.

Infection prophylaxis after HDIT was managed in a similar manner to that of patients after allogeneic SCT. Infectious events were relatively infrequent and manageable. UTIs occurred more frequently than in other studies of autologous SCT for hematologic malignancies, but many patients had histories of recurrent UTIs because of abnormal bladder function and the requirement in some cases of a chronic indwelling catheter. The most significant infection-related event after HDIT was the development of an EBV-PTLD, which is a rare diagnosis after autologous transplantation but has been reported.47,48 The development of EBV-PTLD in this group was associated with the pretransplantation administration of rabbit ATG instead of horse ATG, which resulted in the absence of circulating T cells on day 28.49 Another case of EBV-PTLD, developed in a patient with systemic sclerosis after HDIT, was also associated with the administration of rabbit ATG.46 It was concluded from both of these cases that rabbit ATG, at the dose and schedule used, was more immunosuppressive than horse ATG. Both of these cases illustrate the potential risk of further intensification of high-dose immunosuppressive regimens for treatment of autoimmune diseases. Noninfectious adverse events observed in this study were mostly transient in nature except for the hypothryroidism.

An engraftment syndrome occurred in 13 of the first 18 patients enrolled in the study. The engraftment syndrome can consist of both rash and noninfectious fever after autologous transplantation and has been identified in up to 59% of patients after autologous SCT.50-52 The onset of fever after HDIT was associated with a transient worsening of neurologic symptoms in these MS patients, and in one case, an irreversible increase of the EDSS by 1.0 point. Transient worsening of weakness with the occurrence of fever is commonly observed in MS patients.53 It is unclear why one patient had irreversible loss of neurologic function associated with the engraftment syndrome. With the development of fever after transplantation, there may have been increased production of endogenous proinflammatory cytokines that exacerbated the disease.54 Flares of MS have been noted during treatment with the recombinant cytokine gamma interferon, suggesting that changes in the endogenous cytokine milieu may be important to disease activity.55 A similar case of an irreversible loss of neurologic function associated with fever after HDIT has been reported previously.56 Corticosteroids have been described as effective for the management of the engraftment syndrome.57 Further experience is required with prednisone to confirm its effectiveness, but strategies for control of the engraftment syndrome and fevers may be required to reduce the risk of adverse neurologic events after HDIT.

Since the primary objective of the protocol was to assess safety of HDIT, the follow-up schedule had not been designed to confirm changes in the EDSS of 0.5 points. Treatment failure was defined as an increase in EDSS of 1.0 point or greater compared with baseline.58 Rates of progression after HDIT observed in this study were comparable with the study of HDIT reported by Fassas et al.59 With a median follow-up of 40 months of 23 patients, it was reported that progression-free survival was 76%.59 At one year after treatment, 2 patients had new or enhancing lesions. Patients with SP MS had a higher probability of remaining progression free than those with PP MS. In another study, HDIT was demonstrated to effectively suppress gadolinium-enhancing activity and the development of new T2 lesions in serial MRI studies of the brain in 10 patients with a median follow-up of 15 months.60 In general, this has been confirmed in other studies, but follow-up has been limited.56,61,62 In the present study, 3 of the 25 evaluable patients had MRI evidence of disease activity after HDIT (events not associated with mobilization) and all 3 patients had clinical progression. In general, however, there was no evidence of progression based on T2-weighted burden of disease studies. MRI of the spinal cord was not done, and therefore it cannot be excluded that new lesions there may have been associated with progression in some cases. The presence of oligoclonal bands in the CSF is a potential surrogate marker for an immune response localized to the CNS and, if present, supports the diagnosis of MS. Oligoclonal bands usually persist throughout the course of the disease. In 9 of 12 patients from this current study and in all patients from other published HDIT studies, the CSF remained positive for the presence of oligoclonal bands over time.56,62 The significance of this observation with respect to the clinical status of the patient is unclear.

Loss of brain volume was minimal in a subset of 12 patients at one year after HDIT, and less than that observed after HDIT in a previous study of 5 patients.56 Decreases in brain volume over time have been documented to be objective and reliable markers for the destructive pathologic processes associated with MS.63-66 The course of the brain atrophy may be influenced by prior inflammatory disease activity, but this has not been observed in all studies.65,67 A continued loss of brain parenchyma from axonal degeneration as a consequence of chronic demyelination in the absence of inflammation may result from the loss of trophic support. In this HDIT pilot study, most patients had advanced long-standing disease, and further loss of brain parenchyma and neurologic function might be unavoidable because of continued degenerative changes. Brain volume studies will be required in a larger number of patients with longer follow-up to more fully assess the impact of HDIT on preventing further brain atrophy.

As expected, the toxicities associated with HDIT were greater than with other conventional therapies for MS, but in general were mostly transient and reversible. Important clinical issues in the use of HDIT and autologous SCT for MS were identified and led to successful protocol modifications. There are limits to the degree of immunosuppression that can safely be induced by HDIT and autologous SCT. Patients in this clinical trial had advanced MS with a median baseline EDSS of 7.0 points. A strategy of earlier intervention with HDIT in high-risk patients may be the preferred approach before severe brain injury and irreversible degenerative processes have occurred. Although not done in the study, future studies of HDIT for MS should investigate whether specific T-cell immunity to myelin basic protein is altered by treatment. While the disease stabilization observed in this study is encouraging, the clinical role of HDIT and autologous SCT will require a comparison with conventional treatment of MS in a randomized study.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 22, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3908.

Supported by grants HL36444 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; N01-AI-05419 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; CA15704 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; and H133B980017 from the US Department of Education's National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

Jinan Al-Omaishi died in November 2002 during the preparation of this manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to thank Michael Elliot, MD, Lynn Taylor, MD, David Derrington, MD, and all the neurologists who assisted in the evaluation of study patients, as well as the study coordinators and data technicians. We thank Helen Crawford, Bonnie Larson, Sue Carbonneau, and Connie Chan for their excellent support in preparing this manuscript. We also thank Amgen for their support of the study by their generous contribution of filgrastim (G-CSF).