Abstract

Thrombocytopenia is common in persons infected with relapsing fever Borreliae. We previously showed that the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii binds to and activates human platelets in vitro and that, after platelet activation, high-level spirochete-platelet attachment is mediated by integrin αIIbβ3, a receptor that requires platelet activation for full function. Here we established that B hermsii infection of the mouse results in severe thrombocytopenia and a functional defect in hemostasis caused by accelerated platelet loss. Disseminated intravascular coagulation, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, or splenic sequestration did not play a discernible role in this model. Instead, spirochete-platelet complexes were detected in the blood of infected mice, suggesting that platelet attachment by bacteria might result in platelet clearance. Consistent with this, splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia temporally correlated with spirochetemia, and the severity of thrombocytopenia directly correlated with the degree of spirochetemia. Activation of platelets and integrin αIIbβ3 were apparently not required for bacterium-platelet binding or platelet clearance because the bacterium-bound platelets in the circulation were not activated, and platelet binding and thrombocytopenia during infection of β3-deficient and wild-type mice were indistinguishable. These findings suggest that thrombocytopenia of relapsing fever is the result of platelet clearance after β3-independent bacterial attachment to circulating platelets.

Introduction

Thrombocytopenia can be a complication of many viral, bacterial, fungal, and protozoan infections.1 Platelets, produced in the bone marrow by megakaryocytes, are central to primary hemostasis because of their role in maintaining endothelial integrity.2 In some instances, infection-induced thrombocytopenia is severe enough to cause bleeding. Thrombocytopenia associated with bacterial infections is often thought to occur secondarily to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a generalized activation of the coagulation cascade during overwhelming bacteremia that results in the rapid consumption of platelets.1 Thrombocytopenia associated with viral infections is often caused by the generation of antiplatelet antibodies, with subsequent accelerated platelet clearance, or by the suppression of megakaryopoiesis.3,4 However, a significant percentage of patients with infection-induced thrombocytopenia have no evidence of DIC, antiplatelet antibodies, or bone marrow suppression.1,5-7 One proposed model for thrombocytopenia during infections involves the formation of platelet-microbe complexes, followed by the clearance of these complexes from the circulation.8-12

To investigate how high-level growth of microbes in the blood might lead to thrombocytopenia, we studied relapsing fever caused by arthropod-borne spirochetes of the genus Borrelia.13 Although these spirochetes can infect a number of organs, such as the spleen, liver, heart, and brain, the hallmark of relapsing fever is recurrent high-level (eg, 108/mL) spirochetemia. Each episode of spirochetemia is caused by a serologically distinct population of bacteria. Serotype variation results from the expression of different variable major surface proteins, and it involves gene replacement at a specific expression site.14 The progeny of a single bacterium encode many silent variable major protein genes, and as many as 26 antigenically distinct serotypes of this bacterium can be generated in a single infection.15

Interestingly, thrombocytopenia is a prominent feature of relapsing fever. Petechial rash, epistaxis, hematuria, and mucosal bleeding are common findings in louse-borne relapsing fever.16-19 In North America, relapsing fever is caused mainly by tick-borne spirochetes such as Borrelia hermsii and Borrelia turicatae, and thrombocytopenia is the most common laboratory finding in infected patients.20

Given that relapsing fever spirochetes cause thrombocytopenia and, by growing to high concentrations in the blood, have ample opportunity to interact with blood cells, we have been investigating the interaction of B hermsii with platelets.12 Circulating platelets are found in a relatively nonadhesive “resting” state. Activation of platelets by thrombin, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), or other agonists dramatically increases platelet adhesiveness,21 in part by altering the conformation of the major platelet integrin αIIbβ3 to a high-affinity state.22 We previously found that B hermsii was capable of contact-dependent platelet activation and that, after platelets had been activated, the spirochetes bound efficiently through integrin αIIbβ3.12

The murine model of relapsing fever borreliosis recapitulates a number of pathophysiologic aspects of the human disease and has been used to investigate pathways of immune clearance by the host23-25 and mechanisms of immune evasion14,15 and tissue invasion by the microbe.26 Recent studies indicate that thrombocytopenia also develops in experimentally infected mice.26-28 In the current study, we have investigated thrombocytopenia in the murine model of relapsing fever and have found no evidence of bone marrow suppression, systemic activation of coagulation, or antiplatelet antibodies. Instead, B hermsii–induced thrombocytopenia may result from a direct interaction between bacteria and circulating platelets.

Materials and methods

Borreliastrains

B hermsii DAH was isolated from a patient with relapsing fever northwest of Cheney, WA.29 Notably, this patient had thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 89 000/μL blood) during her acute illness. After treatment and recovery from infection, the patient's platelet count returned to within normal limits (410 000/μL blood). B hermsii HS1, a tick isolate from Spokane, WA,30 was shown previously to efficiently bind and activate human platelets.12 Strains DAH and HS1 are indistinguishable by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.31 B hermsii strains FRO, HAN, MAN, and CON are clinical isolates from the western United States and were previously described.31 B hermsii HS1-Vlp7 was obtained from Dr Alan Barbour, University of California, Irvine.

Mice

The 129Sv/C57BL6 control mice and β3-deficient mice32 were bred and maintained in micro-isolator cages in the Department of Animal Medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS). Normal 4-week-old C57BL6 and C57BL6/SCID mice and mice of the same age that underwent splenectomy were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), whereas CB.17/SCID mice were provided by Dr Robert Woodland (UMMS).

Murine infections

Three- to 5-week-old mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106 spirochetes in 100 μL BSK-H medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO), unless stated otherwise. Control mice were injected with an equal volume of sterile BSK-H medium. To monitor spirochetemia and thrombocytopenia, an aliquot of 5 μL blood was sampled from the tail bleed and diluted immediately into 45 μL citrated anticoagulant (0.11 M sodium citrate/citric acid in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]).12,28 A portion of the sample was examined under dark-field microscope (magnification, × 400) to quantify spirochetemia.26

Quantitation of platelets and platelet-bacterium complexes and characterization of platelet activation

Flow cytometry was used to enumerate platelets28 and to identify and quantify bacterium-platelet complexes in the circulations of infected mice. To identify bacteria and platelets, 10 μL anticoagulated blood sample described above was stained with phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled antimouse platelet CD61 mAb (β3-integrin) (clone 2C9.G2; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) or CD49b mAb (clone Hmα2; PharMingen) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated B hermsii antibodies.12 Samples were fixed in 0.1% formalin in PBS, and platelets with bound bacteria were identified by their FITC fluorescence above the threshold value, set by using an identically stained sample of uninfected murine blood. We previously showed that staining of platelet-bacterium complexes formed in vitro gives rise to a continuum of fluorescence, reflecting both a continuum of bacterial binding as assessed microscopically12 and a continuum of immunoreactivity. In vitro–cultivated B hermsii stained variably with the antiserum used in this study, as assessed by flow cytometry, whereas bacteria harvested from infected mice demonstrated uniform immunoreactivity (data not shown). The difference in immunoreactivities of these populations of bacteria may be that the major surface antigen (the variable major protein) expressed by bacteria cultivated in vitro is distinct from that expressed by host-adapted bacteria.29

To assess platelet activation, blood samples were stained with biotinylated antimouse CD62P (P-selectin, clone RB40.34; PharMingen) and PE-labeled antimouse platelet CD61 mAb (β3-integrin) followed by streptavidin-labeled RED670 (Gibco BRL, Bethesda, MD). As positive control for platelet activation, 10 μL anticoagulated blood described above was treated without or with platelet agonist phorbol myristic acetate (PMA; 20 μM).28 At least 20 000 platelet events were analyzed using a FACSCali-bur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) equipped with a 15-mW, 488-nm, air-cooled argon laser, standard 3-color filter arrangement, and CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Positive and negative controls were used to establish color compensation settings using appropriately tagged, isotype-matched, nonspecific antibodies. Bacterial binding did not diminish the staining (mean fluorescence intensity) of activated platelets by anti–P-selectin or anti–integrin αIIb (the subunit of integrin αIIbβ3)12 (and data not shown).

To assess the response of the residual platelets of thrombocytopenic mice, platelets from these mice and uninfected mice were purified as described.33 Both platelet preparations were incubated with ADP (40 μM; Bio/Data, Horsham, PA), epinephrine (5 μM; Bio/Data) and collagen (20 μg/mL; Chrono-log, Havertown, PA), or thrombin (0.2 U/mL; Chrono-log) for 30 minutes at room temperature, and P-selectin expression or β3-integrin up-regulation was measured.

Analysis of antibody-mediated induction of thrombocytopenia

To examine a possible involvement of antiplatelet antibody in the induction of thrombocytopenia, serum was harvested from wild-type mice 3 days after infection, when they had severe thrombocytopenia (platelet levels approximately 10% of normal). The serum was filter-sterilized, and 300 μL was injected intravenously into naive mice. Platelet counts were monitored by flow cytometry.28

Determination of accelerated clearance of platelets

Mouse platelets were biotinylated in vivo by intravenous infusion of sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimido biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as described.33,34 After 2 hours, the infused mice were infected with B hermsii as described above. An aliquot of 5 μL blood was sampled at various times, diluted, stained with PE-labeled antimouse platelet CD61 mAb and FITC-labeled streptavidin, and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the numbers of biotinylated and nonbiotinylated platelets.

Attachment of B hermsii to murine platelets in vitro

Platelets from wild-type or β3-deficient mice were isolated as described earlier.33 Activated platelets were prepared by adding 0.1 U thrombin to 500 μL platelets, followed by incubation for 20 minutes at room temperature. Bacteria were incubated with platelets at a multiplicity of infection of approximately 2 in Tyrode buffer containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 60 minutes at room temperature.12 Where indicated, EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; final concentration, 10 mM) was added to platelets for 15 minutes before binding. Bacteria-bound platelets were quantitated by flow cytometry as described above.

Bleeding-time measurements

Bleeding time was determined as described by Dejana et al.35 In brief, 2 mm of the distal end of the tail was transected using a razor blade, and the tail was immersed in 0.9% saline at 37°C. The time it took for the blood to cease streaming was recorded as the bleeding time.

Hepatosplenomegaly and bone marrow analysis

To determine the hepatosplenomegaly associated with B hermsii infection, 16 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106 spirochetes. Two mice each were killed on days 0, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 after infection, and their spleens and livers were excised and immediately weighed.

To count the megakaryocytes in the marrow, femurs were removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Five-micrometer sagittal sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Morphologically identifiable megakaryocytes were counted by light microscopy in 20 fields (magnification, × 400).36

Detection of fibrin D-dimers

To detect fibrin D-dimers in the blood of B hermsii–infected mice, groups of C57BL6 mice (5 mice/group) were injected intraperitoneally with saline (negative control) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (positive control; 500 μg Escherichia coli O55:B5 LPS; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or B hermsii strain DAH (106 spirochetes). After 48 hours, mice were anesthetized and blood was drawn by cardiac puncture into citrated anticoagulant. Plasma was isolated after centrifugation at 13 000g and was analyzed for the presence of fibrin D-dimers using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Asserchrom D-Di; Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres, France).37

Results

B hermsiiinfection results in thrombocytopenia and prolonged bleeding

To test whether B hermsii causes thrombocytopenia in infected mice, 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106 spirochetes, and platelet counts were determined during peak spirochetemia (day 2 after infection). Platelet counts in mock-infected mice were within the normal range for mice,28,38 whereas platelet counts were 5- to 20-fold lower in infected mice (Table 1). To determine whether the decrease in platelet counts was associated with a functional defect in hemostasis, we measured the bleeding time in infected mice. The bleeding time in mock-infected mice was approximately 1 minute (Table 1). In contrast, infected mice demonstrated bleeding times at least 5 times longer, consistent with manifestations of bleeding observed in patients with relapsing fever.17-19 The responsiveness of the remaining platelets of the infected mice to the platelet agonists thrombin, collagen/epinephrine, and ADP was comparable with that of the platelets of uninfected mice (data not shown), suggesting that the observed increase in bleeding time resulted from a quantitative rather than a qualitative platelet defect.

Accelerated clearance of platelets in B hermsii–infected mice

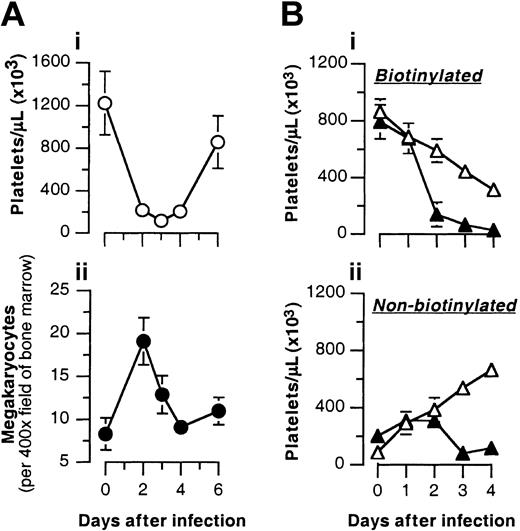

The decreased number of circulating platelets during relapsing fever indicates either decreased platelet production or increased platelet clearance.26,27,39 Diminished production of platelets from the suppression of megakaryopoiesis in the bone marrow can occur during infection40 ; therefore, we measured megakaryocyte numbers in the bone marrow of B hermsii–infected mice. No decrease in the number of megakaryocytes was detected during thrombocytopenia. In fact, the megakaryocyte count increased more than 2-fold during the initial period of thrombocytopenia, then returned to normal levels (Figure 1A). A rapid increase in megakaryocyte count in response to increased platelet clearance has previously been observed during experimental consumptive thrombocytopenia.36 These results indicate that B hermsii–induced thrombocytopenia is not the result of bone marrow suppression, and by exclusion they suggest that thrombocytopenia is likely caused by accelerated platelet consumption.

B hermsii infection results in an increased rate of platelet clearance. (A) B hermsii infection is not associated with diminished numbers of megakaryocytes. 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH. (i) On the indicated days after infection, platelet counts were determined by flow cytometry, and the mice were killed. (ii) Megakaryocytes in hematoxylin-eosin–stained bone marrow sections were visually counted using light microscopy (original magnification, × 400). Shown are the means ± SDs from 20 fields. (B) Accelerated clearance of platelets in B hermsii–infected mice. Numbers of biotinylated (i) and nonbiotinylated (ii) platelets in uninfected (▵) or B hermsii–infected (▴) mice at the indicated day after infection were determined by flow cytometry. Each curve represents the mean ± SD of 5 mice.

B hermsii infection results in an increased rate of platelet clearance. (A) B hermsii infection is not associated with diminished numbers of megakaryocytes. 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH. (i) On the indicated days after infection, platelet counts were determined by flow cytometry, and the mice were killed. (ii) Megakaryocytes in hematoxylin-eosin–stained bone marrow sections were visually counted using light microscopy (original magnification, × 400). Shown are the means ± SDs from 20 fields. (B) Accelerated clearance of platelets in B hermsii–infected mice. Numbers of biotinylated (i) and nonbiotinylated (ii) platelets in uninfected (▵) or B hermsii–infected (▴) mice at the indicated day after infection were determined by flow cytometry. Each curve represents the mean ± SD of 5 mice.

To directly measure the clearance of platelets in B hermsii–infected mice, platelets (and other blood cells) were labeled in vivo by intravenous infusion of a biotinylation agent (see “Materials and methods”). On postinfection days 1 through 4, blood samples from B hermsii–infected or uninfected mice were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the number of biotinylated platelets (present in the circulation at the time of platelet labeling) and the number of nonbiotinylated platelets (newly synthesized) (Figure 1B). The steady rise of nonbiotinylated platelets and the steady fall of biotinylated platelets in uninfected mice is a reflection of normal platelet turnover.33,34 Examination of infected mice showed that by day 2 after infection, the clearance of biotinylated platelets was significantly faster in infected mice than in control mice. Similarly, the clearance of nonbiotinylated platelets was faster in infected than in control mice after postinfection day 2. We conclude that the thrombocytopenia of relapsing fever is caused by accelerated platelet clearance and that the rate of clearance in infected mice is not dramatically influenced by platelet age.

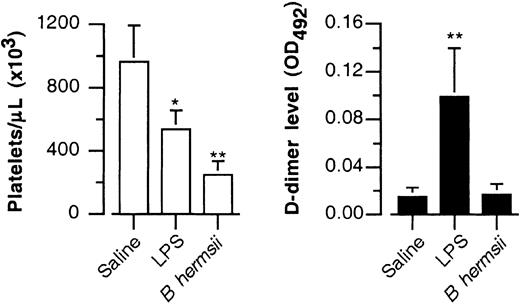

Thrombocytopenia induced by B hermsii infection is not associated with generalized activation of the coagulation cascade

Many, but not all, severe bacterial infections induce thrombocytopenia as a result of DIC, a condition precipitated by the generalized activation of the coagulation cascade in response to bacterial components such as LPS and peptidoglycan.1,5 This systemic activation of coagulation results in generalized thrombus formation and in the rapid consumption of platelets. During this process, the fibrin formed is digested by plasmin, resulting in the release of fibrin D-dimer fragments into the blood and providing a sensitive and specific marker for this condition.37,41 To determine whether the thrombocytopenia of relapsing fever is caused by DIC, fibrin D-dimers were measured in the plasma of C57BL6 mice infected with B hermsii strain DAH. The D-dimer levels were not elevated compared with those of the background levels detected in saline-injected control mice (Figure 2). In contrast, when DIC was induced in control mice by LPS injection, fibrin D-dimers were elevated 6-fold over background levels. These results suggest that the thrombocytopenia of relapsing fever is not a consequence of DIC.

Thrombocytopenia induced by B hermsii infection is not associated with generalized activation of the coagulation cascade. C57BL6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with control buffer, LPS, or 106B hermsii DAH. Two days after infection, platelet counts were determined by flow cytometry (left), and plasma fibrin D-dimer levels (right) were quantitated by ELISA (see “Materials and methods”). Shown are the means ± SDs of 5 mice. *P < .05 compared with saline; **P < .001 compared with saline.

Thrombocytopenia induced by B hermsii infection is not associated with generalized activation of the coagulation cascade. C57BL6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with control buffer, LPS, or 106B hermsii DAH. Two days after infection, platelet counts were determined by flow cytometry (left), and plasma fibrin D-dimer levels (right) were quantitated by ELISA (see “Materials and methods”). Shown are the means ± SDs of 5 mice. *P < .05 compared with saline; **P < .001 compared with saline.

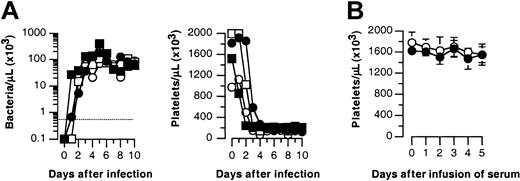

B hermsii–induced thrombocytopenia does not require specific immunity

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura, involving the generation of autoreactive platelet antibodies that lead to platelet-clearance, is another well-characterized pathway for the induction of thrombocytopenia during infection.42-44 To test whether antibody production was required for thrombocytopenia associated with relapsing fever, CB.17/SCID or C57BL6/SCID mice were infected intraperitoneally with B hermsii strain DAH, and bacterial and platelet counts were monitored for 10 days. Infected mice became severely bacteremic by day 3 after infection, and all became severely thrombocytopenic (Figure 3A). To test whether any serum factors (eg, antibodies) were involved in the induction of thrombocytopenia, we harvested serum from wild-type mice on day 3 after infection, when they had severe thrombocytopenia. After filter sterilization, the serum was transferred intravenously to naive mice. No drop in platelet count was observed (Figure 3B). We conclude that B hermsii infection does not trigger thrombocytopenia by eliciting autoreactive platelet antibodies.

B hermsii–induced thrombocytopenia does not require specific immunity. (A) Two CB.17/SCID (•, ▪) or 2 C57BL6/SCID (○, □) mice were infected intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii strain DAH. Bacteremia (left) was measured by visually counting the number of spirochetes in infected blood under dark-field microscopy, and platelet counts (right) were determined by flow cytometry (see “Materials and methods”). Broken line indicates the detection limit for spirochetemia. (B) Platelet counts of mice infused with serum of uninfected (○) and infected thrombocytopenic (•) mice. Shown are the means ± SDs of 5 mice.

B hermsii–induced thrombocytopenia does not require specific immunity. (A) Two CB.17/SCID (•, ▪) or 2 C57BL6/SCID (○, □) mice were infected intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii strain DAH. Bacteremia (left) was measured by visually counting the number of spirochetes in infected blood under dark-field microscopy, and platelet counts (right) were determined by flow cytometry (see “Materials and methods”). Broken line indicates the detection limit for spirochetemia. (B) Platelet counts of mice infused with serum of uninfected (○) and infected thrombocytopenic (•) mice. Shown are the means ± SDs of 5 mice.

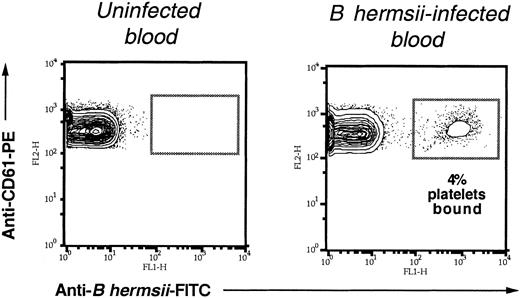

B hermsiibinds to platelets during infection

Interaction between microbes and platelets has been proposed as a mechanism for accelerated platelet clearance,8,45 and we recently demonstrated that B hermsii binds to human platelets in vitro.12 To determine whether the bacterium-platelet binding that we have detected in vitro occurs in the blood of infected mice, we stained and fixed B hermsii and platelets immediately after sampling blood from spirochetemic mice. Flow cytometric analysis of infected blood revealed that a significant percentage of platelets were found attached to spirochetes during infection (Figure 4). The actual percentage of bacterium-bound platelets varied from mouse to mouse but reached as high as 10% (data not shown). Microscopic examination of infected blood also revealed that bacterium-platelet complexes consisted entirely of one bacterium per platelet (data not shown).

B hermsii binds to platelets during infection. Blood from uninfected mice or mice infected with 106B hermsii DAH was analyzed at postinfection day 2, that is, at peak spirochetemia. Samples were double-stained with FITC-conjugated anti–B hermsii antibody and PE-conjugated antiplatelet antibody. The percentage of platelets bound to B hermsii was measured by flow cytometry, as described in “Materials and methods.”

B hermsii binds to platelets during infection. Blood from uninfected mice or mice infected with 106B hermsii DAH was analyzed at postinfection day 2, that is, at peak spirochetemia. Samples were double-stained with FITC-conjugated anti–B hermsii antibody and PE-conjugated antiplatelet antibody. The percentage of platelets bound to B hermsii was measured by flow cytometry, as described in “Materials and methods.”

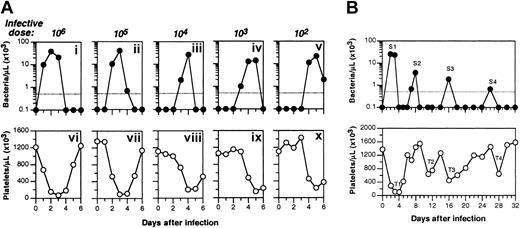

Thrombocytopenia is temporally correlated with spirochetemia

If thrombocytopenia is a result of bacterium-platelet interaction, episodes of spirochetemia are predicted to temporally correlate with episodes of thrombocytopenia. To manipulate the kinetics of spirochetemia, we infected 3- to 5-week-old 129Sv/C57BL6 mice with decreasing numbers of B hermsii strain DAH. Smaller inocula resulted in peak spirochetemia at later times: peak spirochetemia occurred at day 5 after infection with 102 spirochetes (Figure 5Av) but at postinfection day 2 after inoculation with 106 spirochetes (Figure 5Ai). In all cases, the course of thrombocytopenia followed the course of spirochetemia—most severe on the day of or on the day after peak spirochetemia, and then diminishing in severity as spirochetemia diminished (Figure 5A).

Thrombocytopenia is temporally correlated with spirochetemia. (A) 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with decreasing numbers of B hermsii DAH, as indicated. Spirochetemia (i-v) was measured by visually counting the number of spirochetes in the infected blood under dark-field microscopy, whereas platelet counts (vi-x) were determined by flow cytometry. The broken line indicates the detection limit for spirochetemia. (B) Mice inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH, spirochetemia, and thrombocytopenia were monitored as described.28 Peaks of spirochetemia (labeled S1, S2, S3, and S4; top panel) were temporally associated with episodes of thrombocytopenia (labeled T1, T2, T3, and T4; bottom panel).

Thrombocytopenia is temporally correlated with spirochetemia. (A) 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with decreasing numbers of B hermsii DAH, as indicated. Spirochetemia (i-v) was measured by visually counting the number of spirochetes in the infected blood under dark-field microscopy, whereas platelet counts (vi-x) were determined by flow cytometry. The broken line indicates the detection limit for spirochetemia. (B) Mice inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH, spirochetemia, and thrombocytopenia were monitored as described.28 Peaks of spirochetemia (labeled S1, S2, S3, and S4; top panel) were temporally associated with episodes of thrombocytopenia (labeled T1, T2, T3, and T4; bottom panel).

The ability of B hermsii to cause multiple episodes of spirochetemia because of its capacity for antigenic variation14,15 provided another opportunity to correlate spirochetemia and thrombocytopenia. 129Sv/C57BL6 mice inoculated with 106 spirochetes had multiple spirochetemic peaks over a 4-week interval (Figure 5B). Each spirochetemic peak (S1-S4) in Figure 5B was closely followed by an episode of thrombocytopenia (T1-T4), demonstrating that thrombocytopenia and spirochetemia were temporally associated.

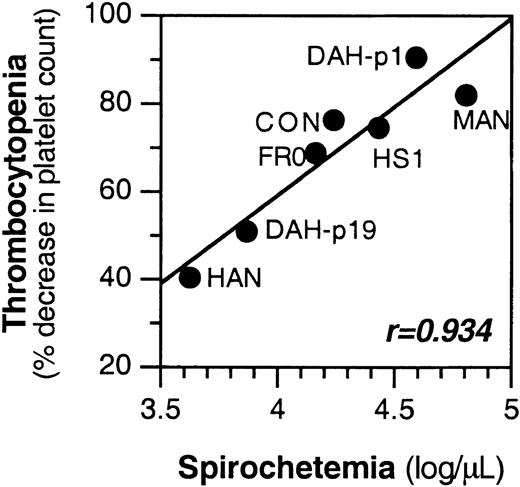

Thrombocytopenia is quantitatively correlated with spirochetemia

We previously showed that the degree of spirochetemia can vary with B hermsii strain: low-passage B hermsii strain DAH (designated DAH p1) grew to 50-fold higher concentrations in the blood than the same strain after 19 in vitro passages (DAH p19).12 To determine whether thrombocytopenia is quantitatively correlated with spirochetemia, we measured spirochete and platelet counts in mice infected with strains DAH p1 or p19 or with 5 other B hermsii strains. Intraperitoneal inoculation into 129Sv/C57BL6 mice of 106 of each these 7 strains resulted in peak spirochetemia by day 2 or 3, but the bacterial concentrations at peak spirochetemia varied over a 50-fold range (Figure 6). The degree of thrombocytopenia correlated remarkably well with the degree of spirochetemia (r = 0.934; Figure 6).

Thrombocytopenia is quantitatively correlated with spirochetemia. 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106 spirochetes of the indicated B hermsii strain. Spirochetemia, determined as described in “Materials and methods,” peaked on day 2 or 3 after infection and is plotted on the x-axis. Platelet counts were also monitored, and the percentage of decrease from day 0 was calculated and plotted on the y-axis. The correlation coefficient (r) is given. Sets of 2 mice were infected with each strain, and the results from each mouse were similar. For clarity, values from only 1 mouse are shown.

Thrombocytopenia is quantitatively correlated with spirochetemia. 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106 spirochetes of the indicated B hermsii strain. Spirochetemia, determined as described in “Materials and methods,” peaked on day 2 or 3 after infection and is plotted on the x-axis. Platelet counts were also monitored, and the percentage of decrease from day 0 was calculated and plotted on the y-axis. The correlation coefficient (r) is given. Sets of 2 mice were infected with each strain, and the results from each mouse were similar. For clarity, values from only 1 mouse are shown.

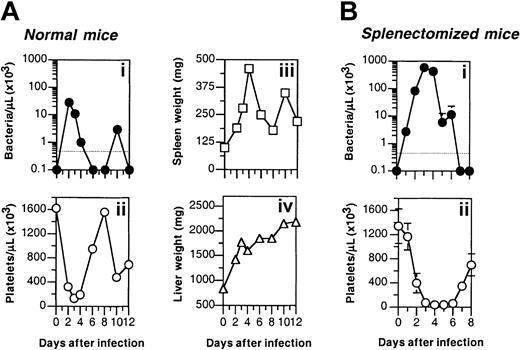

Splenomegaly temporally correlates with thrombocytopenia during B hermsii infection

Accelerated clearance of platelets could result in enlargement of the major organs of the mononuclear phagocytic system, such as spleen and liver. To test this, 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were infected with B hermsii DAH, and at 1- or 2-day intervals, mice were killed and spleen and liver weights and platelet and bacterial counts in the blood were determined. Liver weights were elevated by day 2 after infection and continued to increase through day 12, when the experiment was terminated (Figure 7Aiv). Strikingly, spleen weight correlated inversely with platelet count, peaking at 3 to 5 times the normal spleen weight on the days after thrombocytopenia (Figure 7Aii-iii). The temporal correlation between spirochetemia, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly was consistent with the hypothesis that platelets and bacteria are simultaneously cleared by the mononuclear phagocytic system.

Splenomegaly temporally correlates with thrombocytopenia during B hermsii infection. (A) 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH. On each of the indicated days after infection, 2 mice were killed, and spirochete counts (i), platelet counts (ii), and spleen (iii) and liver (iv) weights were determined. (B) Spirochetemia (i) and thrombocytopenia (ii) in C57BL6 mice after splenectomy.

Splenomegaly temporally correlates with thrombocytopenia during B hermsii infection. (A) 129Sv/C57BL6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH. On each of the indicated days after infection, 2 mice were killed, and spirochete counts (i), platelet counts (ii), and spleen (iii) and liver (iv) weights were determined. (B) Spirochetemia (i) and thrombocytopenia (ii) in C57BL6 mice after splenectomy.

Some forms of thrombocytopenia are associated with splenomegaly caused by splenic pooling of blood cells,46,47 raising the possibility that the thrombocytopenia of relapsing fever is a result of splenomegaly. To determine whether spleen is required for the induction of thrombocytopenia during relapsing fever, we monitored platelet counts in infected mice after splenectomy. As previously reported,25 mice that underwent splenectomy had more severe and prolonged spirochetemia than control mice (Figure 7Bi). These mice also had more severe and prolonged thrombocytopenia, suggesting that splenic clearance or pooling of platelets is not required for thrombocytopenia (Figure 7Bii). Nevertheless, the occurrence of thrombocytopenia in mice after splenectomy does not preclude a role for the spleen in normal mice. It is possible that the liver, another organ of the mononuclear phagocytic system, is involved in platelet clearance during relapsing fever because this organ underwent significant enlargement during infection (Figure 7Aiv).

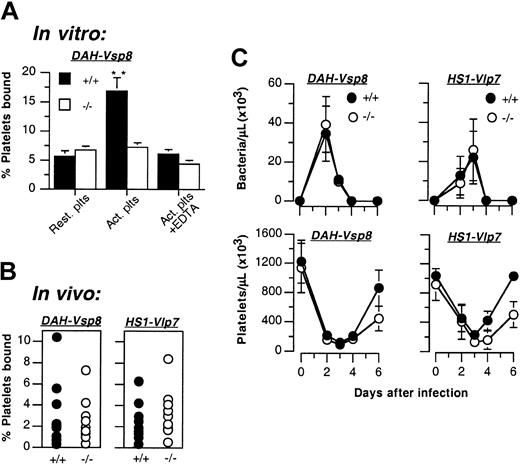

Circulating platelets bound to B hermsii are not activated, and the activation-dependent integrin αIIbβ3 is not required for the induction of thrombocytopenia

We previously showed that B hermsii can activate human platelets in vitro, resulting in an enhanced bacterium-platelet attachment mediated by the activation-dependent integrin αIIbβ3.12 Therefore, we examined the activation state of B hermsii–bound platelets in infected murine blood. Spirochete-platelet complexes in freshly isolated blood from mice infected with strain DAH were identified by flow cytometry, and the activation state of bacterium-bound platelets was assessed by measuring the expression of P-selectin, a widely used platelet activation marker,21 and integrin αIIbβ3, which is expressed at approximately 2-fold higher levels on activated rather than resting platelets.48 By both measures, platelets bound to B hermsii strain DAH displayed characteristics of resting platelets (Table 2). B hermsii strain HS1 activates platelets in vitro more efficiently than does strain DAH, raising the possibility that circulating platelets bound to this strain might demonstrate activated phenotype.12 Nevertheless, during murine infection, strain HS1 neither bound to platelets better than DAH nor induced higher levels of P-selectin or β3-integrin (Table 2).

The observation that spirochete-bound circulating platelets in infected mice did not appear to be activated suggests that bacterial attachment to these circulating platelets is not mediated by integrin αIIbβ3. To address this issue, using a flow cytometric assay, we tested whether integrin αIIbβ3 promoted bacterial attachment to purified murine platelets in vitro. As predicted, the activation of murine platelets resulted in increased bacterial binding (Figure 8A). This enhanced binding was likely caused by the activation-dependent integrin αIIbβ3 because it was abrogated by EDTA, which inhibits integrins, and it was not observed when bacterial binding was assessed using platelets from β3-integrin–deficient mice.32 To test whether integrin αIIbβ3 contributed to bacterial binding in a measurable way in vivo, we infected β3-integrin–deficient 129Sv/C57BL6 mice with B hermsii and measured bacterium-platelet complexes. The level of platelet binding by bacteria in the β3-deficient mice was indistinguishable from that in wild-type 129Sv/C57BL6 controls, regardless of whether the infecting strain was B hermsii DAH or HS1 (Figure 8B). Similarly, the presence or absence of functional αIIbβ3 had no striking effect on the degree or kinetics of spirochetemia and thrombocytopenia induced by these 2 strains, though the return of platelet counts to near normal levels was marginally slower in β3-deficient mice (Figure 8C). These results indicate that although integrin αIIbβ3 is a critical receptor for high-level B hermsii attachment to platelets in vitro,12 it does not significantly contribute to bacterial attachment to circulating platelets or to thrombocytopenia in the infected mouse.

Activation-dependent integrin αIIbβ3 is not required for bacterial attachment or induction of thrombocytopenia. (A) Resting (Rest) or thrombin-activated (Act.) wild-type (+/+; ▪) or β3-integrin–deficient (–/–; □) mouse platelets were incubated with B hermsii DAH-Vsp8 in the presence or absence of 10 mM EDTA, and platelet binding was measured by flow cytometry. Shown are the means ± SDs of 2 independent experiments. **P < .001 with activated platelets from –/–mice. (B-C) 129Sv/C57BL6 wild-type (+/+; •)or β3-integrin–deficient (–/–; ○) mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH or HS1. (B) At peak spirochetemia on day 2 after infection, the percentages of platelets with bound bacteria were quantified by flow cytometry (see “Materials and methods”). Shown are the means ± SDs of 8 mice from each group. (C) On the indicated days after infection, spirochete and platelet counts were determined. Shown are the means ± SDs of 10 mice from each group.

Activation-dependent integrin αIIbβ3 is not required for bacterial attachment or induction of thrombocytopenia. (A) Resting (Rest) or thrombin-activated (Act.) wild-type (+/+; ▪) or β3-integrin–deficient (–/–; □) mouse platelets were incubated with B hermsii DAH-Vsp8 in the presence or absence of 10 mM EDTA, and platelet binding was measured by flow cytometry. Shown are the means ± SDs of 2 independent experiments. **P < .001 with activated platelets from –/–mice. (B-C) 129Sv/C57BL6 wild-type (+/+; •)or β3-integrin–deficient (–/–; ○) mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106B hermsii DAH or HS1. (B) At peak spirochetemia on day 2 after infection, the percentages of platelets with bound bacteria were quantified by flow cytometry (see “Materials and methods”). Shown are the means ± SDs of 8 mice from each group. (C) On the indicated days after infection, spirochete and platelet counts were determined. Shown are the means ± SDs of 10 mice from each group.

Discussion

Thrombocytopenia is a prominent feature of human relapsing fever, but its etiology is unclear. In the current study, we have investigated the mechanism of relapsing fever-associated thrombocytopenia in a murine model. We established that B hermsii infection of the mouse is indeed associated with severe thrombocytopenia and a functional defect in hemostasis. Megakaryopoiesis was stimulated, not reduced, during B hermsii infection, suggesting that the thrombocytopenia was caused by accelerated platelet clearance rather than diminished production. Indeed we found that biotinylated platelets are cleared more rapidly in B hermsii–infected than in uninfected mice. Consistent with this hypothesis, the liver and spleen, organs involved in platelet clearance, were enlarged during infection. The 3 best-characterized causes of accelerated platelet clearance during infection—DIC, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and splenic sequestration—did not appear to play a role. Fibrin degradation products characteristic of DIC were not detected, thrombocytopenia was induced in antibody-deficient (ie, SCID) mice, and splenectomy did not relieve B hermsii–induced thrombocytopenia.

Having shown previously that B hermsii binds to platelets in vitro,12 we tested whether such binding could also be observed during infection. Flow cytometric analysis of blood drawn from infected mice indicated that as many as 10% of circulating platelets were attached to spirochetes. It is likely that our flow cytometric quantitation of bacterial binding by circulating platelets at peak spirochetemia underestimated the true extent of bacterium-platelet interaction: spirochete-platelet complexes might have been rapidly cleared from the circulation and thereby rendered undetectable by flow cytometry. Thus, the 1% to 10% of circulating platelets that were found attached to spirochetes during peak spirochetemia may represent only a “snapshot” of the initial step in a dynamic process involving both the formation of spirochete-platelet complexes and their subsequent rapid clearance. Given that at peak spirochetemia the rate of B hermsii replication12,25 is likely to be greater than the rate of platelet production,33 continuous formation and clearance of spirochete-platelet complexes could result in significant platelet loss. Consistent with this model, the degree of thrombocytopenia correlated well with the degree of spirochetemia; the timing of episodes of thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly were also strikingly correlated with episodes of spirochetemia.

Several features of the murine model for relapsing fever-associated thrombocytopenia parallel previous studies of relapsing fever in humans. For example, bone marrow biopsy samples from patients with thrombocytopenic relapsing fever revealed an increase in megakaryocyte numbers,17 and hepatosplenomegaly is a common feature of human infection.18,39,49,50 Patients with thrombocytopenic relapsing fever show no evidence of DIC, even in the presence of bleeding manifestations.17,18,49 Instead, platelet-spirochete complexes have occasionally been observed in blood smears from patients with relapsing fever.17

In vitro B hermsii activates human platelets and, concomitantly, the major platelet integrin αIIbβ3 in a contact-dependent manner.12 This activation leads to high-level spirochete-platelet binding by way of αIIbβ3.12 In contrast, we obtained no evidence that circulating spirochete-bound platelets were activated during infection. These platelets did not differ from spirochete-free platelets in their expression of P-selectin or β3-integrin, 2 proteins that are expressed at higher levels on activated platelets than on resting platelets. In addition, the efficiency of bacterial binding to circulating platelets was similar in β3-deficient and wild-type mice. It is possible that our inability to detect platelet activation represents the limitation of flow cytometry mentioned above—that is, only cells that remain in the circulation can be sampled and analyzed. It is also possible that B hermsii, like several other platelet agonists such as epinephrine and serotonin,38 activates human platelets more efficiently than it does murine platelets.

Whether platelets undergo activation after spirochete binding during infection, the activation-dependent integrin αIIbβ3 does not appear to be required for the induction of thrombocytopenia by B hermsii. The kinetics and severity of thrombocytopenia were indistinguishable during infection of β3-deficient and wild-type mice. The previously identified contact-dependent platelet activation activity of B hermsii suggests that a binding pathway independent of αIIbβ3 promotes an initial spirochete-platelet interaction.12 Presumably, if platelet clearance during infection is the result of bacterial attachment, this initial αIIbβ3-independent attachment of spirochetes to resting platelets is sufficient to trigger this clearance, and the high-level binding mediated by αIIbβ3 that we observed in vitro is apparently not required.

The precise outcome of platelet-bacterium attachment during infection is still unclear. One can speculate that by inducing thrombocytopenia and compromising hemostasis, this arthropod-borne microbe expedites tick feeding and the subsequent transmission of the pathogen to the arthropod. The saliva of many blood-feeding arthropods, including Ornithodoros ticks that transmit relapsing fever spirochetes, contains inhibitors of platelet aggregation,51-53 presumably to facilitate feeding. It is notable that the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, which is transmitted by the same vector that transmits Borrelia burgdorferi, also induces thrombocytopenia in mice in a manner independent of an intact spleen or lymphocytes.54 Other arthropod-borne pathogens, such as Plasmodium and Trypanosoma, have been shown to bind platelets and induce thrombocytopenia.10,11 An alternative for spirochete-platelet binding may be to promote bacterial attachment to the vessel wall, a step that might diminish clearance by the spleen and liver and lead to a population of immobilized spirochetes that, through replication, efficiently seeds the bloodstream with spirochetes. We previously showed that among a pair of B turicatae strains likely to be isogenic, the ability to bind better to cultured endothelial cells was associated with the ability to achieve higher bacterial concentrations in the blood of infected animals.55 Finally, platelets have also been viewed as host defense cells that promote clearance of circulating microbes. Platelets can release bactericidal peptides,56 and, in several infection models, preexisting thrombocytopenia was associated with decreased microbial clearance.45,57-61 The ability to follow bacteremia, thrombocytopenia, bacterium-platelet attachment, and tissue colonization in the murine model of relapsing fever described here will permit detailed analysis of the role of platelet-spirochete interactions during infection.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 10, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0426.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-AI 37601 (J.M.L.), and P01HL66105 (R.O.H.), and supported in part by Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center grant DK 32520 (I.J.). J.M.L. was an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. R.O.H. is an investigator for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Jorge Benach, James Coleman, and Joe Gebbia for generously providing training in animal infection techniques. We also thank Alan Barbour for providing B hermsii HS1-Vlp7; Robert Woodland for providing CB.17/SCID mice; Jon Goguen, Jenifer Coburn, Guido Majno, Marc Barnard, and Larry Frelinger for providing stimulating discussions; and Yu Liu of the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center at University of Massachusetts Medical School for preparing bone marrow specimens.