Abstract

The degree of redundancy between thrombopoietin (Tpo) and steel factor (SF) cytokine pathways in the regulation of hematopoiesis was investigated by generating mice lacking both c-Mpl and fully functional c-Kit receptors. Double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice exhibited reduced viability, making up only 2% of the offspring from c-Mpl–/–KitWv/+ intercrosses. The thrombocytopenia and megakaryocytopenia characteristic of c-Mpl–/– mice was unchanged in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice. However, the number of megakaryocytic colony forming units (CFU-Mks) was significantly reduced, particularly in the spleen. While KitWv/Wv mice, but not c-Mpl–/– mice, are anemic, the anemia was more severe in double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice, indicating redundancy between Tpo and SF in erythropoiesis. At the primitive cell level, c-Mpl–/– and KitWv/Wv mice have similar phenotypes, including reduced progenitors, colony forming units–spleen (CFU-Ss), and repopulating activities. All of these parameters were exacerbated in double-mutant mice. c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice had 8-fold fewer clonogenic progenitor cells and at least 28-fold fewer CFU-Ss. c-Mpl–/– mice also demonstrated a reduced threshold requirement for nonmyeloablative transplant repopulation, a trait previously associated only with KitW mice, and the level of nonmyeloablative engraftment was significantly greater in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv double mutants. Thus, c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice reveal nonredundant and synergistic effects of Tpo and SF on primitive hematopoietic cells.

Introduction

Hematopoietic cytokines are essential both for effective production of mature blood cells and for maintenance of multipotential progenitors and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). It is well established that extrinsic factors regulate lineage-specific cell survival, differentiation, and maturation.1 For example, erythropoietin (Epo) is necessary to support erythrocyte development,2,3 whereas granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is required for granulocyte development.4 Cytokines may also play an instructive role on lineage commitment decisions of multipotent cells. For example, in the multipotent cell line FDCP-mix, cells can be induced to differentiate along macrophage, neutrophil, or erythroid pathways via macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), G-CSF, or Epo, respectively.5,6 Finally, there is accumulating evidence that early-acting cytokines, including steel factor (SF), Flt3/Flk2 ligand (Flt3L), thrombopoietin (Tpo), interleukin-3 (IL-3), and gp130-associated cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-11 can influence the survival and proliferation of HSCs. This has been shown both by repopulation deficiencies in knock-out mice7-10 and by in vitro expansion of primitive cells in the presence of these cytokines.11-14 SF and Tpo are 2 important cytokines that affect both primitive and mature hematopoiesis.

SF, encoded by the murine Sl locus, binds the c-Kit tyrosine kinase receptor, the product of the murine Kit locus (reviewed in Broudy15 ). Complete loss of function of Kit (KitW) or Sl results in embryonic death with severe macrocytic anemia. Hypomorphic alleles have also been described, which have variable degrees of anemia, reductions in mast cell numbers, infertility, and pigmentation defects. One such allele is the white-viable (KitWv) allele: homozygous KitWv/Wv mice are viable but sterile, white with black eyes, and have macrocytic anemia, while heterozygous KitWv/+ are fertile, have a milder anemia, and have patches of white fur. Early studies examining compound heterozygous KitW/Wv mice found reductions in most clonogenic progenitor populations, including colony-forming unit–erythroid (CFU-E), CFU–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM), and CFU-spleen (CFU-S), as well as poor hematopoietic repopulating ability.16-18 The KitWv allele contains a missense mutation of 2007C>T (Thr to Met), in the kinase domain–encoding sequence that results in partial loss of function.19 In vitro, SF, acting in synergy with early-acting factors such as IL-11 and Flt3L, can support modest expansion of pluripotent HSCs.12

Tpo is a member of the 4 α-helical hematopoietin family and binds to the c-Mpl receptor. Mpl does not have intrinsic kinase activity, but, when activated, it can bind Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) leading to activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and STAT5.20,21 Tpo or c-Mpl knock-out mice have severe thrombocytopenia, with an 80% reduction in the number of circulating platelets.7,22,23 c-Mpl–/– mice also have decreased numbers of clonogenic progenitor cells in multiple lineages and approximately 7-fold reduced competitive repopulation ability.8,24 Tpo alone supports HSC survival in vitro25,26 and acts synergistically with other early-acting factors to induce HSC division.27,28

Due to the similarity of phenotypes of Wv and c-Mpl–/– mice, particularly at the primitive cell level, we investigated the degree of functional overlap between the Tpo-Mpl and SF-Kit signaling pathways. We interbred KitWv/+ and c-Mpl–/– mice to generate double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice, the viability of which was severely limited. We also show that Tpo signaling contributes to residual erythropoiesis in KitWv/Wv mice. Moreover, although the KitWv/Wv mutation does not further reduce platelet or megakaryocyte levels in c-Mpl–/– mice, it does alter megakaryocytic progenitor levels, indicating that SF signaling contributes to megakaryocytopoiesis. We also show synergistic interactions between SF and Tpo signaling in regulation of HSC competitiveness, as reducing the function of c-Mpl or Kit facilitated nonmyeloablative engraftment of wild-type donor hematopoietic cells.

Materials and methods

Animals

The c-Mpl–deficient23 and KitWv (McCulloch and Siminovitch29 ) mice have been described previously. Mice were housed and experiments performed at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute animal facility with the approval of the Melbourne Health Research Directorate Animal Ethics Committee. Compound heterozygous mice (c-Mpl+/–KitWv/+) were produced by mating c-Mpl–/– and KitWv/+ parents. The compound heterozygotes were subsequently interbred or backcrossed to produce offspring of all 9 possible genotypes. c-Mpl genotypes were determined by Southern blotting, and Kit genotypes were inferred from coat color. All mice were analyzed at between 2 and 4 months of age.

Mature hematopoietic cell analysis

Peripheral blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus and analyzed in an automated cell counter Advia 120 Hematology System (Bayer, Tarrytown, NY). Megakaryocytes were enumerated by microscopic examination of hematoxylin and eosin–stained histologic sections of sternal bone marrow and spleen. A minimum of 30 microscopic fields was scored.

In vitro culture of fetal liver erythropoietic cells

Fetuses were harvested at 14.5 days post coitum (dpc) from KitWv/+ or Mpl–/–KitWv/+ intercrosses. Fetal liver (FL) cells were suspended in Iscove modified Dulbecco media (IMDM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and the remaining fetal tissue was used to genotype the Kit locus by a restriction fragment length polymorphism using NsiI. Ter119+ cells were depleted from the FL suspension by incubation with rat anti-Ter119 followed by magnetic column separation (Dynal M450 goat antirat magnetic beads; Carlton, Australia), and the resulting Ter119– suspension was cultured for 1 day in IMDM containing 15% FCS and supplemented with 2 U/mL recombinant human Epo (rhEpo). Cells were then washed and cultured a further 3 days in IMDM 20% FCS without Epo. Erythroid differentiation was measured at days 0 (before and after Ter119 depletion), 1, 2, and 3 by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Cells were incubated on ice with phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled Ter119 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled CD71 (all antibodies from BD Pharmingen, Lexington, KY), and washed with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Sigma, Castle Hill, Australia) prior to analysis on FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA). FACS analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Clonogenic progenitor cell assays

The clonal culture of hematopoietic progenitor cells was performed in 1-mL cultures of 2.5 × 104 (bone marrow) or 105 (spleen) cells as previously described.30 All cells were cultured in 0.3% agar in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 20% FCS. Cytokines were used at the final concentrations of 10 ng/mL murine IL-3, 100 ng/mL murine SF, 2 U/mL rhEpo, and 10 ng/mL murine granulocyte macrophage (GM)–CSF. The cultures were incubated for 7 days at 37° C in a fully humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Agar cultures were then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and sequentially stained with acetylcholinesterase, Luxol Fast Blue, and hematoxylin, and the composition of each colony was determined at 100- to 400-fold magnifications.

Colony forming unit–spleen assay

Bone marrow or FL cells were collected from wild-type, c-Mpl–/–, KitWv/Wv, and c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice in DMEM containing 2% FCS and injected intravenously via the tail vein into C57Bl/6 recipients previously irradiated with 11 Gy of gamma-irradiation from a 137Cs source (Atomic Energy, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Cell doses injected ranged from 7.5 × 104 to 2.0 × 105 cells. Transplant recipients were maintained on oral antibiotic (1.1 g/L of neomycin sulfate; Sigma). Spleens were removed after 12 days and fixed in Carnoy solution (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% acetic acid), and the numbers of macroscopic colonies were counted.

Nonmyeloablative transplants

Bone marrow cells were collected from C57Bl6/Ly5.1 mice in DMEM 2% FCS and injected intravenously into mice of various c-Mpl and Kit genotypes. At 3, 4, 6, and 12 weeks after transplantation, blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus of transplant recipients and analyzed by flow cytometry. Erythrocytes were lysed and leukocytes were incubated with FITC-labeled anti-Ly5.1 and either PE-labeled anti-B220 or a combination of PE-labeled Gr-1 and PE-labeled Mac-1 (all antibodies from BD Pharmingen). All samples were washed with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) prior to analysis on FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

CRU assay

HSCs were detected and evaluated using a limiting dilution transplantation-based assay for cells with competitive, long-term, lymphomyeloid repopulation function. The procedure has been described in detail previously.31 Irradiated B6-Ly5.1 recipients were injected with 5 × 103 to 107 cells, and the blood of these mice was analyzed by FACS 16 weeks after transplantation for evidence of lymphomyeloid repopulation. Mice that had more than 2% donor-derived (Ly5.2+) cells in both lymphoid (B220+) and myeloid (Gr1+ or Mac1+) subpopulations were considered to be repopulated with test cells. Competitive repopulating unit (CRU) frequencies in the test bone marrow sample were calculated by applying Poisson statistics to the proportion of negative recipients at different dilutions using Limit Dilution Analysis software (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada).

Results

Reduced viability of double-deficient Kit and c-Mpl mice

To generate mice doubly deficient for both c-Mpl and c-Kit, we interbred c-Mpl knock-out and KitWv mice, both on C57Bl/6 background. c-Mpl–/– mice are fertile and can be identified by Southern blot genotyping, whereas KitWv/Wv are infertile but can be genotyped by inference from examination of coat color (Kit+/+ are black, KitWv/+ are spotted, and KitWv/Wv are white). Crossing KitWv/+ and c-Mpl–/– mice generated c-Mpl+/–KitWv/+ mice, which were then intercrossed. However, no c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice were generated from these initial matings (data not shown). We then set up a large number of controlled matings in which the c-Mpl genotype of the progeny was obligate, and the Kit genotype could be inferred from coat color (Table 1).

The frequency of KitWv/Wv (white) mice generated on a wild-type (c-Mpl+/+) background was significantly reduced from the expected 1 in 4 (chi-square P = .07). Viability was further reduced in a dose-dependent manner with successive addition of c-Mpl– loss-of-function alleles. c-Mpl+/–KitWv/Wv mice made up only 5% of the offspring from c-Mpl+/+KitWv/+ to c-Mpl–/–KitWv/+ crosses (P = 10–6 compared with expected 1:2:1 ratio). Even more dramatically, c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice accounted for just 5 of 253 (or 2%) of the offspring from c-Mpl–/–KitWv/+ intercrosses (P = 10–16). Thus c-Mpl deficiency, which does not affect viability on its own,23 greatly exacerbates the embryonic lethal phenotype of KitWv/Wv mutations.

Megakaryopoiesis

Previous reports have shown both unique and common hematopoietic deficiencies in mice with c-Mpl or Kit loss-of-function mutations. For example c-Mpl–/– but not KitWv/Wv mice have thrombocytopenia, whereas KitWv/Wv but not c-Mpl–/– mice have anemia. We directly compared blood cell production in c-Mpl–/– versus KitWv/Wv mice to investigate the relative importance of the 2 cytokine pathways in various lineages. We then examined these same cell compartments in double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice to investigate redundancy between the 2 pathways.

As shown in Table 2, c-Mpl–deficient mice have significantly reduced numbers of platelets and megakaryocytes. Circulating platelets were reduced 12-fold compared with wild-type mice, and megakaryocytes were reduced 5- and 4-fold in spleen and bone marrow, respectively. A similar examination of the thrombopoietic compartment in KitWv/Wv mice revealed normal-to-elevated numbers of megakaryocytes and a normal level of circulating platelets, indicating that c-Kit is largely dispensable for normal thrombopoiesis. Mice lacking both c-Mpl and functional Kit alleles also had significantly lower megakaryocyte and platelet counts than normal. However, as these were not significantly different from those in mice lacking c-Mpl alone, we could show no additive or synergistic effect of the Kit mutation on mature thrombopoiesis in Mpl-deficient mice.

c-Mpl–/– mice had significantly reduced colony-forming units–megakaryocyte (CFU-Mks) in the bone marrow (P = .0002; Table 2), further validating the importance of Tpo signaling at multiple stages of megakaryopoiesis. The rare but detectable splenic CFU-Mk population was not affected in c-Mpl–/– mice, implicating this as a site for Tpo-independent thrombopoiesis. Although the Wv mutation did not appear to affect terminal differentiation of megakaryocytes, we did find a significant reduction in megakaryocytic progenitors in these mice, particularly in the spleen (P = .0004). Double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv had significant reductions in CFU-Mks, and both bone marrow and spleen were affected. However, neither bone marrow CFU-Mks nor splenic CFU-Mks were significantly reduced compared with those in c-Mpl–/– or KitWv/Wv mice, respectively.

Erythropoiesis

We next examined the impact of Tpo and SF signaling on the erythroid lineage. Circulating red blood cell (RBC) counts and hematocrits were normal in c-Mpl–/– mice (Table 3). In contrast, both of these parameters were significantly reduced in KitWv/Wv mice, initially suggesting that Kit but not c-Mpl is involved in erythropoiesis. However, mice with the combined c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv genotype had a more severe anemia than those lacking Kit alone. This synergistic effect indicates that while Tpo signaling is normally dispensable for steady-state erythropoiesis, it has a compensatory function in the absence of SF signaling.

To examine erythropoiesis in more detail, we examined 14.5-dpc embryos from Mpl–/–Wv/+ and Mpl+/+Wv/+ intercrosses. Hematopoietic assays were performed on the fetal liver cells, and the remaining fetal tissue was used for genotyping. Colony forming units–erythroid (CFU-E) were reduced in KitWv/Wv but not c-Mpl–/– embryos, with no additive effect from the loss of both genes (Table 3).

Flow cytometric analysis of Ter119 and CD71 expression on fetal liver cells can be used to identify stages of fetal erythropoietic cell development as they progress from R1 (Ter119–CD71lo) through to R5 (Ter119+CD71lo)32 (Figure 1A). There was an apparent reduction of immature R1 cells in KitWv/+ and KitWv/Wv embryos, with a concomitant allele dosage-dependent increase in the more mature R3 compartment (Figure 1B). No such effect was detected in c-Mpl–deficient embryos. When Ter119– cells were selected by column purification, the KitWv-dependent reduction in R1 cells was retained. However, Ter119– cells from all 6 genotypes were equally capable of in vitro differentiation, shifting to R2 then R3 and finally R4 and R5 phenotypes over 4 days in culture (data not shown).

Fetal liver erythropoietic compartments. (A) Erythropoietic compartments defined by Ter119 and CD71 expression; maturation is shown by the progression from the least mature (R1) to most mature (R5) erythroid population. (B) Average proportion (±SD) of fetal liver cells in each compartment. KitWv/Wv embryos have a reduced proportion of cells in R1, independent of the c-Mpl genotype.

Fetal liver erythropoietic compartments. (A) Erythropoietic compartments defined by Ter119 and CD71 expression; maturation is shown by the progression from the least mature (R1) to most mature (R5) erythroid population. (B) Average proportion (±SD) of fetal liver cells in each compartment. KitWv/Wv embryos have a reduced proportion of cells in R1, independent of the c-Mpl genotype.

Myelopoiesis

Mature cells in other lineages were also examined by automated blood cell analysis. Total white blood cell (WBC) counts were normal in c-Mpl–/–, KitWv/Wv, and c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice. There were decreased percentages of circulating neutrophils and eosinophils in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice with a concomitant increase in the percent of lymphocytes (Table 4).

We next examined the effects of SF and Tpo signaling on production and/or maintenance of myeloid progenitor cells. Both Tpo and SF are important regulators of progenitor cell production. Accordingly, we found significant reductions in the total CFC contents from both c-Mpl–/– and KitWv/Wv adult mice. Interestingly, the progenitor cell defect was most pronounced in the bone marrow of c-Mpl–/– mice (P = .007, Figure 2) and in the spleen of KitWv/Wv mice (P = .0002). Double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice had severe progenitor deficiencies in both bone marrow and spleen, and these were exacerbated over those observed in mice with single gene Mpl–/– or KitWv/Wv mutations. Spleen cells from c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice contained 8-fold fewer CFCs than in wild-type mice (P = .00006) and 2-fold fewer than in the affected KitWv/Wv spleen (P = .007). Similarly, c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv had 3-fold fewer bone marrow CFCs compared with wild type (P = .0009) but a more moderate 1.5-fold reduction compared with the low number in c-Mpl–/– bone marrow (P = .002).

Clonogenic progenitor cell levels in mice with loss-of-function c-Mpl and/or Kit alleles. Colony-forming cells (CFCs) were determined by agar culture of 25 000 bone marrow cells, 100 000 spleen cells, or 10 000 fetal liver cells from wild-type, c-Mpl–/–, KitWv/Wv, or c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice. Shown are the means ± SDs of CFCs per dish. There were significant decreases in both bone marrow– and spleen-derived CFCs from c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice. In contrast, CFC levels were normal in all types of fetal liver cells. α indicates P < .001 versus wild type; β, P < .001 versus c-Mpl–/–; and γ, P < .001 versus KitWv/Wv.

Clonogenic progenitor cell levels in mice with loss-of-function c-Mpl and/or Kit alleles. Colony-forming cells (CFCs) were determined by agar culture of 25 000 bone marrow cells, 100 000 spleen cells, or 10 000 fetal liver cells from wild-type, c-Mpl–/–, KitWv/Wv, or c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice. Shown are the means ± SDs of CFCs per dish. There were significant decreases in both bone marrow– and spleen-derived CFCs from c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice. In contrast, CFC levels were normal in all types of fetal liver cells. α indicates P < .001 versus wild type; β, P < .001 versus c-Mpl–/–; and γ, P < .001 versus KitWv/Wv.

Myeloid progenitor levels were not significantly altered from wild type in 14.5-dpc fetal liver cells in c-Mpl–/–, KitWv/Wv, or c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv animals (Figure 2).

Colony-forming units–spleen

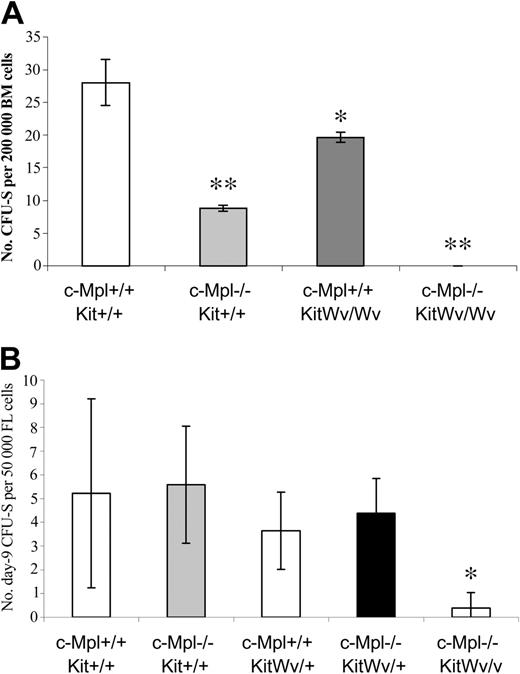

We next examined the effects of loss-of-function mutations in c-Mpl and/or Kit genes at the more primitive multipotent progenitor stage, represented by the colony-forming unit–spleen (CFU-S). Bone marrow cells from adult c-Mpl–/– and KitWv/Wv mice both have reduced day-12 CFU-S contents (Figure 3A). Loss of c-Mpl results in a more than 3-fold CFU-S12 reduction, whereas KitWv/Wv mice have a more moderate 1.4-fold reduction. A more dramatic effect on CFU-S12 was found in double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice, where the CFU-S content was reduced at least 28-fold. In fact, we were unable to detect any CFU-S in mice injected with 200 000 cells. We have been unable to further refine the CFU-S12 frequency in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv bone marrow, due to the extremely low viability of these mice.

CFU-S reductions in mice with c-Mpl and/or Kit mutations. Colonies (mean ± SD) on the spleens of mice injected 12 days earlier with 200 000 bone marrow cells (A) or 9 days earlier with 50 000 fetal liver cells (B). *P < .05 versus wild type; **P < .001 versus wild type.

CFU-S reductions in mice with c-Mpl and/or Kit mutations. Colonies (mean ± SD) on the spleens of mice injected 12 days earlier with 200 000 bone marrow cells (A) or 9 days earlier with 50 000 fetal liver cells (B). *P < .05 versus wild type; **P < .001 versus wild type.

To overcome the unavailability of adult c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice, day-9 CFU-Ss were measured from fetal liver cells of mice lacking c-Mpl and/or c-Kit function. There was no significant difference in the number of CFU-S9 in mice with the KitWv/+, c-Mpl–/–, or KitWv/+c-Mpl–/– genotypes relative to wild-type mice. However, there was a dramatic deficit of CFU-Ss in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv fetal liver cells, which contained 13-fold fewer CFU-S9 than wild-type littermates (Figure 3b).

Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation

Competition for the limited number of HSC niches in the bone marrow normally prevents nonmyeloablative engraftment at bone marrow cell doses that would otherwise give stable repopulation of myeloablated hosts.33 Reduced HSC function may therefore be reflected by a reduced ability of endogenous HSCs to outcompete exogenous donor HSCs. For example nonmyeloablated Kit mutant mice (either KitW/Wv or KitW41/W41) can be fully engrafted without preconditioning by as little as 105 bone marrow cells,34 whereas wild-type BALB/C mice require doses on the order of 108 bone marrow cells.35 Consistent with these studies, we found that nonmyeloablated C57BL/6 hosts were engrafted only by doses more than 108 cells (Table 5). The threshold engraftment dose was reduced in c-Mpl–/– hosts, which permitted short-term engraftment by 6 × 106 cells and long-term engraftment by 6 × 107 cells. Double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/+ mice had a further reduction of the engraftment threshold to just 106 cells. Thus, both c-Mpl and c-Kit signaling are required to maintain a fully competitive HSC compartment.

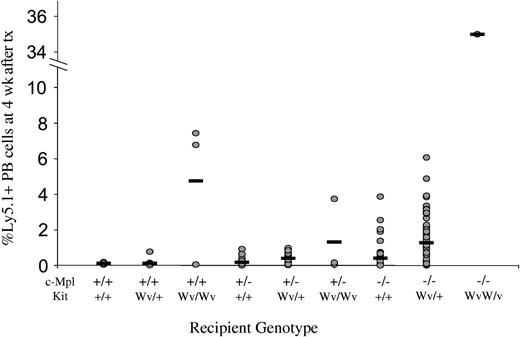

This synergistic effect of deficiencies in the Mpl and Kit signaling pathways was also evident in the magnitude of engraftment achieved by a standardized dose of 106 B6-Ly5.1 bone marrow cells into nonmyeloablated mice. In wild-type recipients, engraftment was virtually undetectable at 0.12 ± 0.05% Ly5.1+ cells in the peripheral blood at 4 weeks. Engraftment increased to 4.75 ± 4.08% in KitWv/Wv hosts, but was not significant in c-Mpl–/– hosts (0.41 ± 0.67%). However, the same treatment in a single available c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mouse resulted in 35.50% donor-type peripheral blood cells at 4 weeks, higher than that achieved in mice lacking either single gene (Figure 4). Thus, Tpo and SF signaling pathways act synergistically to regulate the HSC compartment, and simultaneous disruption to both pathways causes severe reduction in HSC competitiveness.

Engraftment of Ly5.1 cells into nonmyeloablated c-Mpl and KitWv mice. Levels of Ly5.1+ cells in the peripheral blood of nonmyeloablated mice injected 4 weeks prior with 106 B6-Ly5.1 bone marrow cells in individual mice (circles) and group means (horizontal bars). Engraftment level escalates with increasing numbers of loss-of-function c-Mpl or Kit alleles. tx indicates transplantation.

Engraftment of Ly5.1 cells into nonmyeloablated c-Mpl and KitWv mice. Levels of Ly5.1+ cells in the peripheral blood of nonmyeloablated mice injected 4 weeks prior with 106 B6-Ly5.1 bone marrow cells in individual mice (circles) and group means (horizontal bars). Engraftment level escalates with increasing numbers of loss-of-function c-Mpl or Kit alleles. tx indicates transplantation.

Competitive repopulating units

To directly assess the impact of c-Mpl and/or Kit deficiencies on the hematopoietic stem cell compartment, quantitative analysis was carried out using the limit dilution competitive repopulating unit (CRU) assay to detect cells capable of competitive, long-term, lymphomyeloid repopulation. As shown in Figure 5, both c-Mpl–/– and KitWv/Wv homozygous single gene alterations cause striking 20- to 30-fold reductions in CRU levels. KitWv/+ mice exhibited CRU at near-normal levels, and c-Mpl–/–KitWv/+ bone marrow showed no greater reduction in CRUs from c-Mpl–/– mice.

Competitive repopulating units in the bone marrow of mice with c-Mpl– and Wv alleles. CRU frequencies are expressed as the number of CRUS (95% confidence intervals) per 107 bone marrow cells.

Competitive repopulating units in the bone marrow of mice with c-Mpl– and Wv alleles. CRU frequencies are expressed as the number of CRUS (95% confidence intervals) per 107 bone marrow cells.

Discussion

Loss-of-function alleles of the murine cytokine receptor genes c-Mpl and Kit have distinct and complementary phenotypes on hematopoiesis. At the mature cell level, mutations in c-Mpl and Kit affect the thrombopoietic and erythropoietic lineages, respectively.7,15,22,23 Moreover, although most other mature lineages are not affected in either single mutant, they both have deficiencies at the stem cell level.8,16-18,24 We demonstrate here, in double-mutant c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice, which lack both Tpo and SF receptors, that these 2 cytokine pathways contribute overlapping and nonredundant actions in mature and multipotential hematopoietic compartments.

Platelet counts were unaltered in KitWv/Wv compared with wild-type mice, and in KitWv/Wvc-Mpl–/– compared with c-Mpl–/– mice. Similarly, megakaryocyte numbers were not affected by the KitWv/Wv mutation on a wild-type or c-Mpl–/– background. These results suggest that Tpo and not SF signaling is required for effective mature thrombopoiesis. The KitWv/Wv mutation did, however, significantly reduce the level of megakaryocyte progenitors, particularly in the spleen. Thus, while dispensable for terminal megakaryocytopoiesis, SF appears to be required, along with Tpo, for full wild-type production of megakaryocyte progenitor cells.

The existence of an extrinsic factor that regulates thrombopoiesis in the absence of Tpo is suggested by the residual platelet production in c-Mpl–/– or Tpo–/–7,22 mice and by the robust rebound platelet production in c-Mpl–/– mice following 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) administration.36 Yet double mutants involving c-Mpl and a host of other genes have failed to identify the in vivo thrombopoietic regulator. G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), and IL-11, many of which stimulate megakaryocyte growth in vitro, all failed to exacerbate the thrombopoietic defect of c-Mpl–/– mice.37-39 SF seemed a likely candidate as a regulator of Tpo-independent or emergency thrombopoiesis, as 5-FU failed to induce rebound thrombopoiesis in Sl/Sl or KitWv/+ mice.40 Responses to 5-FU are characterized by significant expansion of both multipotent and committed progenitor cells. Our data suggest that while SF may play a role in 5-FU–induced expansion of progenitors including CFU-Mks, it appears not to contribute significantly to residual platelet production in c-Mpl–/– mice.

Although c-Mpl–/– mice do not suffer anemia, there is some evidence that Tpo plays a role in early erythropoiesis. For example, adult c-Mpl–/– mice have reduced CFU-E contents.24 Moreover, while administration of Tpo to wild-type mice caused limited effects on circulating RBC content, it did increase the more primitive blast-forming unit–erythroid (BFU-E) in bone marrow and spleen.41 Administration of the cytokine to mice with damaged erythropoietic systems had more dramatic effects at the mature cell level, rescuing the anemia in EpoR–/– mice42 or increasing CFU-E and reticulocyte counts in myelosuppressed mice.41 Our finding that the c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mutations cause a more severe anemia than either single-gene mutation shows that c-Mpl does contribute to residual erythropoiesis on a KitWv/Wv background. Thus, although the effects of Tpo signaling are restricted to primitive erythropoietic cells in normal mice, it may also contribute to mature erythropoiesis in stressed or damaged hematopoietic states.

The megakaryocytic and erythroid lineages are developmentally linked by a common bipotent precursor. Megakaryocytic erythroid progenitor (MEP) cells, which are largely contained in the IL7Rα–Lin–c-kit+Sca-1–FcγRloCD34– subfraction of murine bone marrow, form colonies containing both megakaryocytic and erythroid cells.43 The importance of Tpo and SF signaling on both early thrombopoiesis and erythropoiesis suggests that these cytokines might regulate such a common precursor. It will be of interest in future studies to examine the MEP population in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice.

SF and Tpo are both members of a rare group of cytokines that regulate both mature cell production and multipotential hematopoietic cells including the HSC. Supplementing in vitro primary hematopoietic cell cultures with either SF or Tpo, particularly in combination with other early-acting factors, can induce HSC division and increase the recovery of totipotent cells by preventing differentiation and/or facilitating self-renewal.25,28,44,45 Consistent with these in vitro studies, primitive cell deficiencies have been described in mice with loss-of-function alleles in Tpo or SF pathways. Tpo–/– or c-Mpl–/– mice have reduced numbers of progenitor cells of multiple lineages, including CFU-Mk, CFU-GM, CFU-E, and CFU–granulocyte-erythrocyte-megakaryocyte-macrophage (CFU-GEMM).24 c-Mpl–/– mice were further shown to have 10-fold reductions in CFU-S.8 Kit or Sl mutations also cause reductions in most progenitor lineages, including BFU-E, CFU-E, and CFU-GM, as well as a 4-fold reduction in CFU-S. We have shown here that Tpo and SF signaling pathways both have essential and nonoverlapping roles at the progenitor cell level. Total CFC content in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice was more reduced than in either single mutant. Interestingly, the c-Mpl mutation had the greatest effect on bone marrow–derived CFCs, while the Kit mutation affected mostly spleen-derived CFCs, and the combined mutant had significant reductions in both compartments. The CFU-S compartment was severely affected in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mice, with at least 28-fold reductions of these multipotent cells in adult bone marrow and 13-fold reductions in fetal liver. These results clearly demonstrate the synergy of the Tpo and SF pathways in regulation of multipotent cells.

Synergistic effects between early-acting growth factors are required to achieve stem cell self-renewal in vitro. While some single growth factors can maintain long-term repopulating cells in culture, multiple factors are required for expansion.25,44,45 Recent findings indicate that both Tpo signaling (via JAK2) and SF signaling are required for in vitro self-renewal of multipotent hematopoietic cells.46 However, expansion of long-term repopulating cells can be achieved in H2K–BCL-2 transgenic bone marrow cells with a single growth factor (SF), indicating that one of the in vitro requirements is inhibition of HSC apoptosis.47 Possible mechanisms for the Tpo-mediated regulation of HSCs have recently been unveiled, including inhibition of apoptosis via p5348 and activation of self-renewal via HoxB4.49

KitW/Wv mice have the unique feature of being stably lymphomyeloid repopulated by as few as 105 transplanted wild-type cells in the absence of myeloablative conditioning,34,50 suggesting that their own HSCs are inferior and/or fewer in number and therefore can be replaced by the introduced HSCs. Here we show that while doses of 6 × 107 bone marrow cells were unable to reconstitute hematopoiesis in unconditioned wild-type mice, doses of 6 × 106 and 6 × 107 cells achieved short-term and long-term repopulation, respectively, in c-Mpl–/– mice. The threshold dose was further reduced to just 106 cells in c-Mpl–/–KitWv/+ mice. The synergy between c-Mpl and Kit was particularly evident when comparing the level of engraftment achieved by nonmyeloablated recipients of 106 cells. There was a clear escalation of repopulation achieved with increasing receptor-deficient alleles, culminating at 35% donor-type cells in the c-Mpl–/–KitWv/Wv mouse.

HSC self-renewal is dependent not only on the types of cytokines present but also on their relative concentrations. The ligand-receptor threshold model postulates that HSC self-renewal requires maintenance of critical signals above a threshold level.51 For example, maximal expansion of long-term culture initiating cells (LTC-ICs) requires 30 times higher cytokine concentrations than maximal expansion of progenitors.52 In theory, serial reductions in receptor levels caused by adding Wv or c-Mpl–null alleles could also lead to declining self-renewal probabilities, and this could explain the escalating ability of these mice to accept nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplants.

The extent to which these and other cytokines have overlapping functions is a fundamental question in cytokine biology. Compensation by similarly acting cytokines can be proved only by removal of multiple factors, as shown here for Tpo in erythropoiesis. Conversely, demonstrations of synergy between cytokines with indistinguishable individual phenotypes show that the 2 factors act independently on a common cell type. This is the case for Tpo and SF signaling on thrombopoiesis and stem cell competitiveness. Such independent regulation by multiple cytokines underscores the importance of extrinsic regulation on HSC behavior.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 11, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1522.

Supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Canberra, Australia (Program Grant 257500); the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the J. D. and L. Harris Trust; the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society fellowship (J.A.); and MuriGen.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The excellent technical assistance and animal husbandry of Jason Corbin, Naomi Sprigg, Janelle Mighall, Sally Cane, Elizabeth Viney, Elaine Major, Kathy Hanzinikolas, Theresa Gibbs, Fiona Berryman, Ben Radford, Chris Evans, Shauna Ross, Sonia Guzzardi, Jaclyn Cushen, Enza Brullo, Tracey Kemp, and Amanda Hoskins are very gratefully acknowledged.