Comment on Prandoni et al, page 3049

An advantage of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is its lower risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH).1 In this issue of Blood, Prandoni and colleagues question whether heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is reduced by low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) in medical patients.

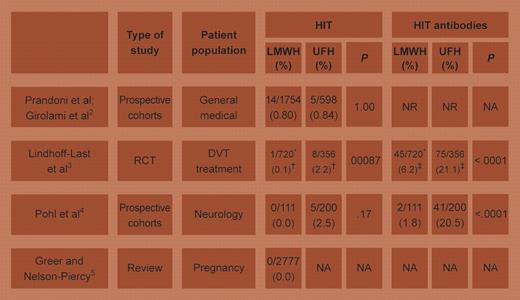

Prandoni and colleagues prospectively evaluated 1754 medical patients who received LMWH for prophylaxis or treatment of thrombosis. HIT was observed in 14 patients (0.80%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43%-1.34%), a frequency similar to the authors' previous prospective cohort study2 of 598 medical patients receiving unfractionated heparin (UFH, 0.84%; 95% CI, 0.1%-1.6%). Thus, this new report infers that LMWH might not reduce HIT in medical patients. This contrasts with the approximate 10-fold reduction in HIT with LMWH compared with UFH for surgical thromboprophylaxis.1 FIG1

Studies comparing UFH and LMWH in medical patients, plus a large review of LMWH treatment during pregnancy. Tests of significance are by Fisher exact test (2-tailed). RCT indicates randomized controlled trial; DVT, deep-vein thrombosis; NA, not applicable; and NR, not reported. *Combined short- and long-term–treated LMWH groups. †Endpoint shown is symptomatic thrombosis associated with antibody formation (as per Table 2 in Lindhoff-Last et al3 ); for true HIT endpoint (defined as thrombocytopenia plus positive antibody), values are LMWH = 0/762 vs UFH = 1/375 (0.3%);P = .33. ‡Per Table 2 in Lindhoff-Last et al.3 Illustration by A. Y. Chen.

Studies comparing UFH and LMWH in medical patients, plus a large review of LMWH treatment during pregnancy. Tests of significance are by Fisher exact test (2-tailed). RCT indicates randomized controlled trial; DVT, deep-vein thrombosis; NA, not applicable; and NR, not reported. *Combined short- and long-term–treated LMWH groups. †Endpoint shown is symptomatic thrombosis associated with antibody formation (as per Table 2 in Lindhoff-Last et al3 ); for true HIT endpoint (defined as thrombocytopenia plus positive antibody), values are LMWH = 0/762 vs UFH = 1/375 (0.3%);P = .33. ‡Per Table 2 in Lindhoff-Last et al.3 Illustration by A. Y. Chen.

Previous studies of medical patients suggested that LMWH likely confers a lower risk of HIT (see table).3-5 Lindhoff-Last et al3 found a reduced frequency of anti–platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin antibodies (surrogate marker for risk of HIT) in a randomized comparison of LMWH and UFH for treatment of deep-vein thrombosis; their study also suggested that thrombotic events linked to antibody formation were reduced by LMWH. In neurology patients, Pohl et al4 noted a marked reduction in antibody formation with LMWH compared with UFH, and a corresponding (nonsignificant) reduction in HIT frequency. Prandoni and colleagues tested for antibodies only when HIT was clinically suspected.

Why did this new study observe so much apparent HIT with LMWH? One possibility is that medical patients, who are usually admitted nonelectively with acute illness, are more likely to be falsely diagnosed with HIT. Indeed, in a placebo-controlled study6 of enoxaparin for medical thromboprophylaxis, 4 of 5 subjects with thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (a scenario suggesting HIT) had actually received placebo. In contrast, surgical thromboprophylaxis studies of HIT have focused on elective orthopedic surgery,1 a setting in which patients are generally well and nearing discharge at the time HIT typically manifests. The potential for false diagnosis increases if a relatively nonspecific laboratory assay is performed, such as an immunoassay that detects (non–platelet-activating) immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgA anti-PF4/heparin antibodies. In this regard, a strength of the new report is that 11 of the 14 patients with putative HIT had a positive platelet activation assay, and the median absorbance value of the immunoassay for anti-PF4/heparin IgG was rather high (1.25 units). Thus, most of these patients likely had HIT.

As generation of the HIT antigens depends upon the appropriate stoichiometric concentrations of PF4 and heparin, factors such as transient perioperative platelet activation and PF4 release, and postoperative thrombocytosis, may accentuate differences in immunogenicity of different heparin preparations or the pathogenic potential of the antibodies formed.

In contrast to a recent consensus conference recommendation,7 Prandoni et al suggest that medical patients receiving LMWH should undergo routine platelet count monitoring for HIT. Given the important implications of these new data, their “outlier” status (see table) leads us to urge that HIT and HIT antibody end points be included in future studies of medical patients receiving LMWH. ▪