Abstract

Histamine, leukotriene C4, IL-4, and IL-13 are major mediators of allergy and asthma. They are all formed by basophils and are released in particularly large quantities after stimulation with IL-3. Here we show that supernatants of activated mast cells or IL-3 qualitatively change the makeup of granules of human basophils by inducing de novo synthesis of granzyme B (GzmB), without induction of other granule proteins expressed by cytotoxic lymphocytes (granzyme A, perforin). This bioactivity of IL-3 is not shared by other cytokines known to regulate the function of basophils or lymphocytes. The IL-3 effect is restricted to basophil granulocytes as no constitutive or inducible expression of GzmB is detected in eosinophils or neutrophils. GzmB is induced within 6 to 24 hours, sorted into the granule compartment, and released by exocytosis upon IgE-dependent and -independent activation. In vitro, there is a close parallelism between GzmB, IL-13, and leukotriene C4 production. In vivo, granzyme B, but not the lymphoid granule marker granzyme A, is released 18 hours after allergen challenge of asthmatic patients in strong correlation with interleukin-13. Our study demonstrates an unexpected plasticity of the granule composition of mature basophils and suggests a role of granzyme B as a novel mediator of allergic diseases.

Introduction

The incidence of allergic diseases, such as asthma, has reached epidemic proportions in industrialized countries, representing a major public health problem and economic burden.1-3 The pathophysiology leading to bronchial hyperreactivity, mucus secretion, and tissue remodeling involves complex interactions between resident cells and leukocytes attracted at sites of inflammation.2,3 Local allergen provocation of allergic patients has been most useful in studying the timed events of these interactions in vivo, leading to the conclusion that the so-called late-phase reaction occurring hours after allergen exposure is most relevant for the symptoms in allergic diseases. Most studies and reviews have focused on the roles of T cells and eosinophils,2,3 although 20 years ago an important involvement of basophils had been postulated based on the distinct mediator profile found immediately and late after allergen exposure.4 Indeed, more recent studies using an antibody specific for basophil granules showed that basophils rapidly infiltrate the challenged tissue.5,6 Thus, basophil granulocytes should be considered as key effector cells in Th2-type immune responses and allergic inflammation.7-9 Human basophils are also a prominent source of the mediators histamine and leukotriene C4 (LTC 4),10 and the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13,11-15 all major players in asthma. Like mast cells, they express high-affinity IgE receptors and harbor histamine in their granules. We and others, however, showed that they are more closely related to eosinophils since they share many receptors for cytokines and chemokines (eg, eotaxin receptors, CCR3), indicating similarities in their trafficking and modes of activation.15,16 In murine immunology, the function of basophil-like cells has been similarly neglected,17 although IL-4–producing FcϵRI+ non-B/non-T cells were described 10 years ago.18 However, several recent studies now document the importance of murine basophils in Th2-type immune responses and chronic allergic inflammation.19-21

In contrast to other granulated leukocytes, little is known about the makeup of basophil granules. The composition of granule proteins and regulation of their expression has been most thoroughly studied in neutrophils.22-24 Developing neutrophils undergo a timed program of expression and packing of granule proteins for primary, secondary, and tertiary granules. It is thus generally assumed that the composition of granule proteins of mature granulocytes is fixed once these cells leave the bone marrow.22,23

The effector functions of human basophils are strongly enhanced by IL-3, IL-5, GM-CSF, and nerve growth factor (NGF).10,25-27 These cytokines are released by T cells and mast cells (MCs) and are thus found at sites of allergic inflammation.2,3,28,29 Among them, IL-3 is the most potent priming cytokine of basophils and the major regulator of IL-4 and IL-13 expression.10,11,13-15,25 Furthermore, IL-3 has the longest duration of action and can also induce phenotypic alterations of mature basophils.12,15,30-32

Addressing the question whether cytokines may affect the composition of basophil granules, we found that IL-3 strongly induces mRNA for granzyme B (GzmB), a 28-kDa serine protease thought to be restricted to the lymphoid lineage that is a major effector of granule-mediated cytotoxicity.33 IL-3 selectively promotes de novo expression of GzmB protein in human basophils, but not in other granulocyte types. In vitro, GzmB is induced in basophils in parallel with IL-13, and both mediators are found in vivo in a highly correlated manner in the lavage fluids in allergic late-phase reactions after segmental allergen challenge of asthmatic patients. Thus, GzmB must be considered as a novel basophil-derived mediator of allergic inflammation.

Materials and methods

Cell stimuli

The complement product C5a was purified from yeast-activated human serum.10 Anti-FcϵRIα mAb 29C6, directed against the non–IgE-binding epitope of the high-affinity IgE receptor α-chain, was from Roche (Nutley, NJ). fMLP (Novabiochem, Laufelfingen, Switzerland), rhMCP-1, rhEotaxin-1, and rhNGF (Preprotech, London, England), and rhIL-2 (BD-Biosciences, Basel, Switzerland) were purchased from commercial sources. rhIFN-α, rhIFN-γ, and rhIL-5 were provided by Roche (Basel, Switzerland) and rhGM-CSF and rhIL-3, by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland).

Leukocyte isolation and purification

Basophils,14 eosinophils, and neutrophils were purified from peripheral blood of healthy adult volunteers. Briefly, venous EDTA-blood (180 mL) was collected and left to sediment in 6% dextran (Amersham, Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). Leukocytes were enriched for basophils using a 2-step discontinuous Percoll gradient (1.0791 and 1.0695 g/mL; Amersham, Biosciences) and further purified by negative selection using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) basophil isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The purity of isolated basophils ranged between 95% and 99%. Following basophil depletion, remaining granulocytes (pellet fraction) were separated using a single-step Percoll gradient (1.0915 g/mL). Neutrophils and enriched eosinophils collected at the interphase and in the pellet, respectively, were subjected to erythrocyte lysis. Purified neutrophils were scarcely contaminated (< 2%) with eosinophils. Eosinophils were further purified to more than 95% by negative selection using anti-CD16 and anti–glycophorin A magnetic beads (both from Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of isolated granulocytes was assessed by Giemsa staining.

Natural killer (NK) cells were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using a negative selection kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (NK-Cell Isolation Kit-II; Miltenyi Biotec).

Cell culture and mediator release measurements.

Granulocytes were cultured in complete culture medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 [Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA] 10% heat-inactivated FCS [Seromed, Basel, Switzerland], and antibiotics [100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin]). For release experiments, basophils (0.2 × 106 cells in 200 μL) were cultured in 96-well U-bottom tissue-culture plates at 37°C, 5% CO2. Following stimulation, cells were collected by centrifugation. Cell pellets were lysed by snap-freezing and thawing in the original volume of medium. Cell lysates and supernatants were further used for the measurements of mediators, cytokines, and granzymes.

Tryptase was measured with the ImmunoCAP analyser and reagents from Phadia (Uppsala, Sweden). IL-4 and IL-13 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Eli-pair kit; Diaclone, Besançon, France) according to the manufacturer's protocols. GzmA and GzmB production were measured by ELISA, as described.34 Histamine and LTC4 were measured by fluorometry and radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIA), respectively.26

Culture of basophils with supernatants of human mast cells

Human mast cells were isolated from intestinal tissue obtained from healthy sections after surgery of tumor patients as described.29 After purification using positive selection with anti–c-Kit–coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec), mast cells were cultured for 10 days with 100 ng/mL SCF followed by 2 weeks with 20 ng/mL IL-4 + 100 ng/mL SCF. Before the collection of supernatants, mast cells (> 99% purity) were washed, suspended at 1 × 106 cells/mL in fresh medium containing SCF only, and cultured for 24 hours with or without 100 ng/mL anti-FcϵRIα mAb. Supernatants were centrifuged through a Biomax 100K membrane (Millipore, Volketswil, Switzerland) to remove any residual anti-FcϵRIα mAb and added in a 1:1 dilution to basophils (3.6 × 106 cells/mL) in fresh medium. Where indicated, mast cell supernatants were preincubated for 10 minutes with 10 μg/mL anti–IL-3 antibody (affinity-purified goat anti–human IL-3; R&D, Minneapolis, MN).

Flow cytometry

For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Fix-and-Perm Cell Permeabilization kit (Caltag, Burlingame, CA). Cells were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 5% FCS and stained with fluorochrom-labeled mAbs: anti–GzmB-PE (mIgG1, clone GB11; Serotec, Dusseldorf, Germany), anti–GzmA-FITC (mIgG1, clone CB9), anti–perforin-FITC (mIgG2b, clone δG9), or isotype control mAbs (mIgG1, clone MOPC-21; mIgG2b, clone 27-35) (all from BD-Biosciences). For surface staining, basophils were incubated with anti-hST2 mAb (IgG1, clone B12; MBL) or control mAb (mIgG1, clone 107.3; BD-Biosciences) in PBS supplemented with 10% donor serum, followed by goat anti–mouse IgG PE-F(ab′)2 (Serotec). Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSCalibur (BD-Biosciences). At least 5 × 104 events were acquired.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were precipitated out of the cell suspension with 10% trichloroacetic acid, separated in NuPAGE 12% Bis-Tris gels (20 μg of protein per line) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Invitrolon; Invitrogen, Frederick, MD). Antibodies used for the detection were as follows: anti-GzmB mAb (GB-4),34 anti-Pim1 mAb (sc-13513; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti–P-Stat5(Tyr694) (9351; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and anti–α-defensin HNP-1/3 mAb (Serotec). Secondary HRP-labeled goat antimouse and goat antirabbit antibodies were from Bio-Rad (Reinach, Switzerland). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL-Kit; Amersham, Otelfingen, Switzerland). For loading controls, stripped membranes were incubated with an anti–β-actin mAb (clone AC-15; Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Granzyme B mRNA measurements by reverse-transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from freshly isolated and cultured basophils using RNeasy-Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To generate cDNA, RNA was transcribed by SuperScript II RNase H`Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Random hexamer primers, first-strand buffer, and DTT were from Invitrogen; PCR Nucleotide Mix and RNAsin from Promega (Mannheim, Germany). Real-time PCR was carried out using commercially predesigned primers and probes for GzmB (Hs00188051_m1) and PBGD (Hs00609297_m1) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR was run on an ABI prism 7700 sequence detector using universal cycling conditions and data were analyzed using the Sequence Detector software from Applied Biosystems. The amount of GzmB mRNA, normalized to an endogenous reference (PBGD) and relative to a calibrator (freshly isolated basophils), is given by 2–ΔΔCt and designated as fold change.

Immunofluorescence

Cytospin preparations of basophils were fixed with 1.33% paraformaldehyde in saturated aqueous pikrinic acid for 10 minutes, washed with PBS, and blocked in TBS/PBS (1:1) containing 1% goat serum for 1 hour. Incubation with anti-GzmB mAb (20 μg/mL, IgG1; Hoelzel Diagnostika, Koln, Germany) or isotype control mAb (20 μg/mL, IgG1; BD-Biosciences) followed by a goat anti–mouse IgG Alexa-Fluor 488–conjugated F(ab′)2 (1 to 1000 dilution; Molecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands). DNA was stained with DAPI (1 μg/mL; Fluka, Munich, Germany). Images were acquired using constant settings on a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 60×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective lens using FITC and DAPI filter sets. A Nikon DXM 1200 digital camera was used to capture images.

Cytotoxicity assay

51Chromium release cytotoxic assay was performed against the MHC-I–deficient, human B-lymphoblastoid cell line 721.221.35,36 Briefly, 721.221 cells were labeled with Na 512CrO4 (100 μCi [3.7 MBq]/106 cells; Amersham) for 1 hour at 37°C. Target cells were washed and seeded on U-bottom 96-well plates at 2000 cells per well in 100 μL. Effector cells (basophils or NK-92 cells)35 were then added in 100 μL medium at an effector-target ratio of 15:1, 30:1, and 60:1 and cultured during 10 hours. Control wells for spontaneous chromium release contained 2000 labeled and 20 000 unlabeled target cells in 200 μL per well. Maximum 51Cr release was determined in target cells lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100. The cytotoxicity was estimated as percentage of cell lysis according to the following formula: cell lysis % = [(experimental release – spontaneous release)/(maximum release – spontaneous release)] × 100. Z-VAD-fmk (z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp(OMe)-fluromethylketone) and Z-IETD-fmk (z-Ile-Glu(OMe)-Thr-DL-Asp(OMe)-fluromethylketone) (BACHEM, Bubendorf, Switzerland) were used at concentrations of 50 μM.

Segmental allergen provocation of allergic patients with asthma and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) analysis

For details see Table S1 (available at the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Briefly, segmental provocation was performed in 23 patients in separate lung segments with saline and the relevant allergen.28 In all the patients, BAL was performed separately in the allergen- and saline-challenged segments 10 minutes after challenge and BAL fluids were recovered. Brochoscopy and BAL were repeated after 18 hours in 13 patients, or after 48 hours in 6 patients and after 162 hours in 4 patients. BAL fluids were stored at –70°C until analysis. For quantitative measurements of the mediators by ELISA, the BAL fluids were concentrated by centrifugation using tubes with 5000-kDa cut-off filters, and each concentration factor was calculated by weight determinations. After ELISA, these values were then used to calculate the original BAL concentration of GzmB, GzmA, and IL-13. Approval was obtained from the University Hospital Bern and University Klinikum Rostock institutional review boards for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

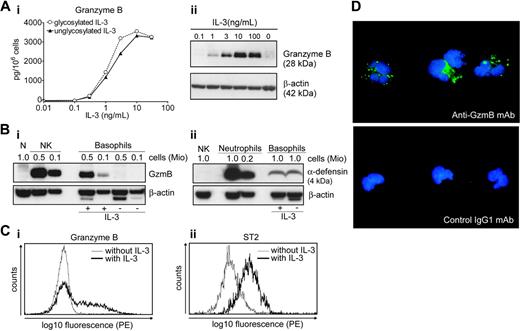

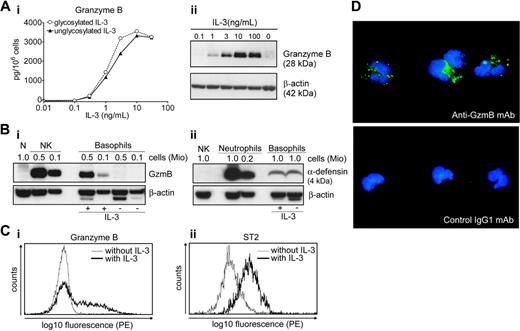

IL-3 induces granzyme B in mature blood basophils without detectable granzyme A and perforin

IL-3 promotes a rapid, strong (of 3 to 4 orders of magnitude), and reversible induction of GzmB mRNA in human basophils, as determined by TaqMan quantitative RT-PCR (Table 1). On the level of the induction of GzmB protein, IL-3 shows a threshold effect at 0.3 ng/mL, an ED50 of 1 to 3 ng/mL, and a plateau reached at 10 ng/mL, as determined by GzmB ELISA and Western blotting of cell lysates (Figure 1A; for variability of GzmB expression see Figure S1). No GzmB was detected in basophils cultured in medium (Figure 1A-B), with the exception of rare cases in which a slight induction became detectable (Figures 4C and 5). As a positive control, lysates of NK cells were included in the blots indicating that the GzmB content of IL-3–treated basophils approximates that found in NK cells (Figure 1B). In contradiction with a recent report,37 no GzmB was detected in neutrophils. To further compare the composition of granule constituents in basophils, neutrophils, and NK cells, we performed immunoblots for neutrophil α-defensin-1/3 (HNP-1/3). As expected,22-24 neutrophils contain high levels of HNP-1/3, in contrast to lower levels found in basophils that are unaffected by IL-3 and NK cells that lack this peptide.

In order to examine the induction of GzmB at the population level, we used intracellular staining of GzmB analyzed by flow cytometry. The data in Figure 1C confirm the induction of GzmB by IL-3 and also show a broad distribution in the intensity of staining, indicating some heterogeneity in the capacity of basophils to express this enzyme. Searching for other markers that are up-regulated by IL-3 we identified ST2, an IL-1 receptor family member involved in Th2 responses that is preferentially expressed in murine Th2 cells.38-40 Figure 1C shows an IL-3–induced up-regulation of ST2 resulting in a parallel shift of the entire basophil population, indicating that basophils are able respond to IL-3 in a uniform manner. Examination of GzmB subcellular localization by immunofluorescence microscopy revealed its granular cytoplasmic distribution (Figure 1D), consistent with the hypothesis that this protein is sorted to the granule compartment.

Expression of 2 other granule constituents of cytotoxic lymphocytes,33 granzyme A (GzmA) and perforin, was not detectable in basophils cultured without or with IL-3. Using several experimental approaches including flow cytometry and GzmA ELISA, no intracellular GzmA was observed in basophils above the limits of the assays (< 100 pg/106 basophils), while blood NK cells and NK-92 cells, a human activated NK cell line, contained even higher levels of GzmA than GzmB. Furthermore, no signal for perforin was detected by flow cytometry and Western blotting, in contrast to NK cells serving as positive controls. No GzmA, GzmB, or perforin could be detected in neutrophils (data not shown).

IL-3 induces granzyme B expression in human basophils. (A) Dose-dependent induction of granzyme B in basophils stimulated with IL-3. (i) Basophils were cultured with different concentrations of unglycosylated E coli–derived or glycosylated CHO-derived recombinant human IL-3 for 24 hours. The GzmB content was then determined by a specific ELISA in cell lysates. A representative experiment (mean of triplicates) out of 3 is shown. (ii) Basophils were cultured without or with different concentrations of IL-3 as indicated for 24 hours. GzmB expression was analyzed in cellular protein extracts by Western blotting. Actin is shown as a loading control. The variability of GzmB induction at a maximally effective concentration of IL-3 in basophils isolated from different donors is shown in Figure S1. (B) Expression of GzmB by NK cells and human basophils, but not neutrophils. Basophils were cultured in the absence or presence of IL-3 (10 ng/mL) for 20 hours. Protein extracts prepared from cultured basophils or freshly isolated neutrophils (N) and NK cells (NK) were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GzmB mAb (i), and anti–α-defensin-1/3 mAb (ii). The number of cells corresponding to the protein amount loaded on a gel is indicated above the lines. Actin is shown as a loading control. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments with cells from different donors. (C) Heterogeneous expression of GzmB in basophils. Intracellular expression of GzmB (i) and cell surface expression of ST2 (ii) were analyzed by flow cytometry in basophils cultured for 20 hours without and with IL-3 (10 ng/mL). (D) GzmB staining shows a cytoplasmic granular pattern. Cytospin preparations of basophils cultured for 20 hours with IL-3 (10 ng/mL) were stained with anti-GzmB mAb (green, top) or isotype-matched control (mouse IgG1) (green, bottom). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Shown are merged images created in Adobe Photoshop 8.0.1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) without any alteration of the original digital images.

IL-3 induces granzyme B expression in human basophils. (A) Dose-dependent induction of granzyme B in basophils stimulated with IL-3. (i) Basophils were cultured with different concentrations of unglycosylated E coli–derived or glycosylated CHO-derived recombinant human IL-3 for 24 hours. The GzmB content was then determined by a specific ELISA in cell lysates. A representative experiment (mean of triplicates) out of 3 is shown. (ii) Basophils were cultured without or with different concentrations of IL-3 as indicated for 24 hours. GzmB expression was analyzed in cellular protein extracts by Western blotting. Actin is shown as a loading control. The variability of GzmB induction at a maximally effective concentration of IL-3 in basophils isolated from different donors is shown in Figure S1. (B) Expression of GzmB by NK cells and human basophils, but not neutrophils. Basophils were cultured in the absence or presence of IL-3 (10 ng/mL) for 20 hours. Protein extracts prepared from cultured basophils or freshly isolated neutrophils (N) and NK cells (NK) were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GzmB mAb (i), and anti–α-defensin-1/3 mAb (ii). The number of cells corresponding to the protein amount loaded on a gel is indicated above the lines. Actin is shown as a loading control. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments with cells from different donors. (C) Heterogeneous expression of GzmB in basophils. Intracellular expression of GzmB (i) and cell surface expression of ST2 (ii) were analyzed by flow cytometry in basophils cultured for 20 hours without and with IL-3 (10 ng/mL). (D) GzmB staining shows a cytoplasmic granular pattern. Cytospin preparations of basophils cultured for 20 hours with IL-3 (10 ng/mL) were stained with anti-GzmB mAb (green, top) or isotype-matched control (mouse IgG1) (green, bottom). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Shown are merged images created in Adobe Photoshop 8.0.1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) without any alteration of the original digital images.

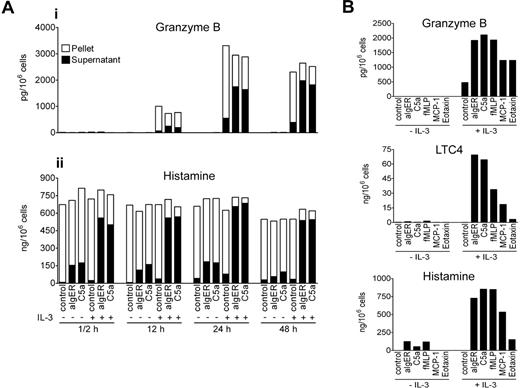

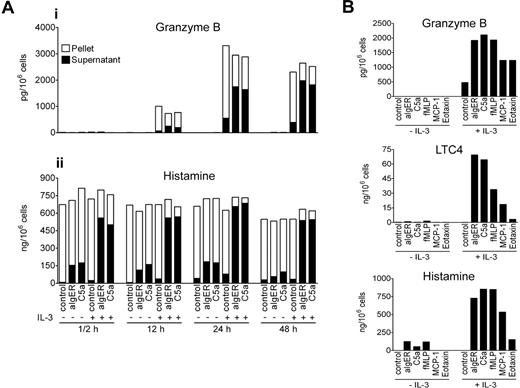

Induced granzyme B is sorted into basophil granules and can be released in response to IgE-dependent and -independent agonists

The best evidence for sorting of GzmB into the granule compartment implies the demonstration of its release upon degranulation together with other basophil granule components, such as histamine. We thus triggered exocytosis of basophils with 2 potent stimuli that use distinct types of receptors and signaling pathways, with anti-FcϵRIα to cross-link IgE receptors or with C5a to activate the G-protein–coupled receptor CD88. Cells were incubated for various time intervals without or with IL-3 before inducing degranulation, followed by measurements of cell-free and cell-associated histamine and GzmB (Figure 2A). Indeed, GzmB was released in response to both stimuli, and the relative proportion that was mobilized appeared to increase with the time, consistent with a time-dependent sorting into the granule compartment following induction and synthesis. Release of GzmB by IL-3–primed basophils was also induced by another strong agonist, fMLP, and by weaker agonists, MCP-1, a ligand of CCR2,41 and eotaxin, a selective agonist of CCR3,16 together with histamine release and LTC4 formation (Figure 2B).

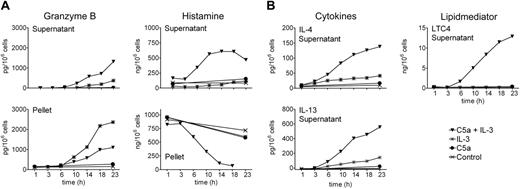

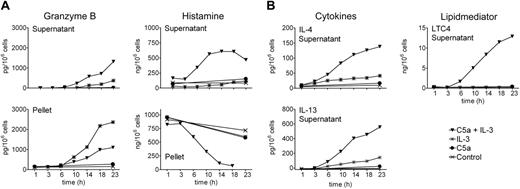

Continuous granule exocytosis, granzyme B secretion, LTC4 formation, and cytokine production induced by C5a and IL-3

We previously showed that acute priming of basophils by IL-3 permitting C5a-induced lipid mediator release and enhancing degranulation requires a preincubation with IL-3 for 5 minutes or more, while no effect was observed when the order of the stimuli was reversed.10 However, prolonged culture of blood basophils with a combination of C5a and IL-3 leads to continuous formation of LTC4 in parallel with the expression and release of high levels of IL-4 and IL-13, a phenomenon that does not depend on the order of the stimuli added, but requires, apart from the presence of IL-3, ongoing signaling through the C5a receptor.13-15,42 This model of a late-phase response was now used to investigate the expression and/or release of GzmB, together with histamine, LTC4, IL-4, and IL-13. In order to minimize the anaphylactic exocytosis of histamine in response to a bolus of C5a at 37°C, this agonist was added on ice just before culture at 37°C. Figure 3 shows that this alteration in stimulus addition did not affect the regulation of IL-4/IL-13 release and LTC4 formation reported previously.14 Of interest, the combined action of C5a and IL-3 also leads to a slow late phase of degranulation as evidenced by the secretion of histamine during 3 to 23 hours in parallel with IL-4/IL-13 expression. IL-3 does not require the cooperation of C5a to optimally induce GzmB, and C5a neither directly promotes nor alters IL-3–induced GzmB expression, as evidenced by the sum of the cell-free and cell-associated product. However, culture of basophils in the presence of C5a plus IL-3 results in an enhanced protracted release of GzmB, indicating concomitant sorting and release through the granule compartment.

Time course of IL-3–induced expression of granzyme B, and its exocytosis in response to different basophil agonists. (A) Release of granzyme B by degranulation of basophils upon IgE-dependent or IgE-independent stimulation. Purified basophils were cultured in medium alone or exposed to a maximally effective concentration of IL-3 (10 ng/mL) for the indicated time periods and subsequently stimulated with buffer (control), anti-FcϵRIα mAb (100 ng/mL, aIgER), or C5a (10 nM) for 30 minutes. GzmB was measured in the cell supernatants and in pellets by ELISA. The whole bar gives an estimation of total GzmB for every condition. Histamine was measured in the supernatants and in the pellets as an indicator of basophil degranulation. A representative experiment (mean of triplicates) is shown. In experiments performed with cells from different donors, GzmB released by basophils cultured with IL-3 for 24 hours was on average 1870 pg GzmB/106 basophils (range, 1150-4600 pg; 9 donors) upon stimulation with C5a, and 2150 pg GzmB/106 basophils (range, 1310-4920 pg; 5 donors) upon IgE-receptor cross-linking. (B) Exocytosis of GzmB is induced by diverse agonists. Basophils were cultured with or without IL-3 (10 ng/mL) for 20 hours before stimulation with anti-FcϵRIα mAb (100 ng/mL; aIgER), C5a (10 nM), fMLP (2.5 μM), MCP-1 (100 nM), or eotaxin (100 nM) for 30 minutes. Released GzmB, histamine, and LTC4 were measured in the cell supernatants. Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment are shown. An identical pattern of results with the same order of efficacy of these agonists was observed with cells from 3 different donors.

Time course of IL-3–induced expression of granzyme B, and its exocytosis in response to different basophil agonists. (A) Release of granzyme B by degranulation of basophils upon IgE-dependent or IgE-independent stimulation. Purified basophils were cultured in medium alone or exposed to a maximally effective concentration of IL-3 (10 ng/mL) for the indicated time periods and subsequently stimulated with buffer (control), anti-FcϵRIα mAb (100 ng/mL, aIgER), or C5a (10 nM) for 30 minutes. GzmB was measured in the cell supernatants and in pellets by ELISA. The whole bar gives an estimation of total GzmB for every condition. Histamine was measured in the supernatants and in the pellets as an indicator of basophil degranulation. A representative experiment (mean of triplicates) is shown. In experiments performed with cells from different donors, GzmB released by basophils cultured with IL-3 for 24 hours was on average 1870 pg GzmB/106 basophils (range, 1150-4600 pg; 9 donors) upon stimulation with C5a, and 2150 pg GzmB/106 basophils (range, 1310-4920 pg; 5 donors) upon IgE-receptor cross-linking. (B) Exocytosis of GzmB is induced by diverse agonists. Basophils were cultured with or without IL-3 (10 ng/mL) for 20 hours before stimulation with anti-FcϵRIα mAb (100 ng/mL; aIgER), C5a (10 nM), fMLP (2.5 μM), MCP-1 (100 nM), or eotaxin (100 nM) for 30 minutes. Released GzmB, histamine, and LTC4 were measured in the cell supernatants. Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment are shown. An identical pattern of results with the same order of efficacy of these agonists was observed with cells from 3 different donors.

Continuous granule exocytosis and granzyme B secretion upon simultaneous stimulation of basophils with C5a and IL-3. Shown is a time course of basophil exocytosis, GzmB formation and release, lipid mediator formation, and cytokine expression in response to IL-3 and C5a. Basophils were cultured in medium alone, with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), with C5a (10 nM), or with the combination of C5a and IL-3 for indicated time periods. C5a was added to the cells at 4°C before culture at 37°C. IL-3 addition followed 30 minutes later at 37°C. (A) GzmB and the basophil granule marker histamine were measured in cell supernatants and pellets. (B) LTC4 formation and cytokine secretion (IL-4 and IL-13) were measured in the cell supernatants only. Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment (out of 3) are shown.

Continuous granule exocytosis and granzyme B secretion upon simultaneous stimulation of basophils with C5a and IL-3. Shown is a time course of basophil exocytosis, GzmB formation and release, lipid mediator formation, and cytokine expression in response to IL-3 and C5a. Basophils were cultured in medium alone, with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), with C5a (10 nM), or with the combination of C5a and IL-3 for indicated time periods. C5a was added to the cells at 4°C before culture at 37°C. IL-3 addition followed 30 minutes later at 37°C. (A) GzmB and the basophil granule marker histamine were measured in cell supernatants and pellets. (B) LTC4 formation and cytokine secretion (IL-4 and IL-13) were measured in the cell supernatants only. Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment (out of 3) are shown.

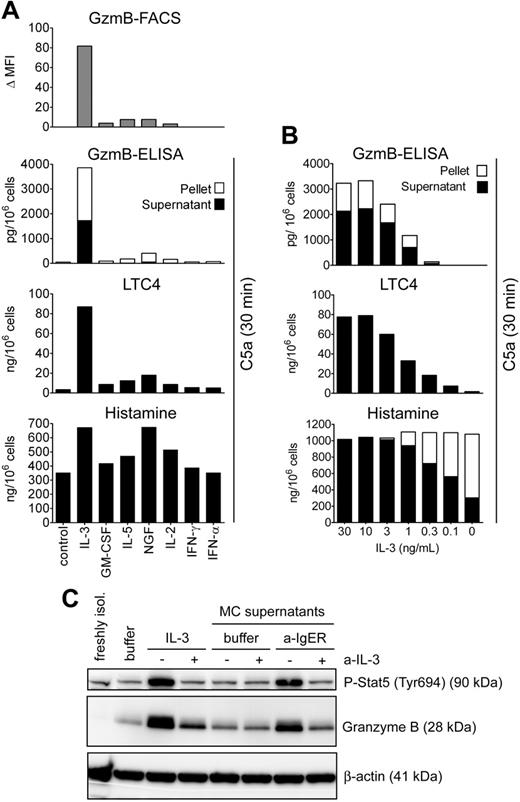

Induction of granzyme B expression by cytokines and supernatants of IgE-activated mast cells

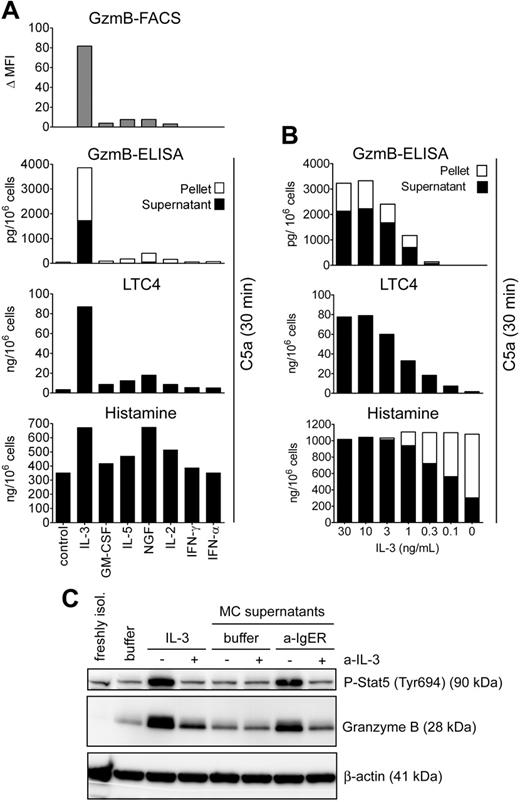

We next tested the ability of several cytokines to induce the expression of GzmB in human basophils (Figure 4A). We chose 4 growth factors, IL-3, IL-5, GM-CSF, and NGF, which all acutely prime basophils with similar efficacy,10,25,26 as well as cytokines thought to enhance cytotoxic functions of lymphocytes (IL-2, interferon-α, and interferon-γ). The efficacy of IL-3 to induce GzmB was rather unique since only weak effects were observed in response to other basophil-priming cytokines. Of interest, late priming for C5a-induced LTC4 formation31,32 and the induction of GzmB expression shows an identical pattern and order of efficacy of the cytokines (IL-3 > > > NGF > IL-5 > GM-CSF), while IL-3 and NGF were similarly effective in enhancing C5a-induced degranulation. A similar pattern of responses was found using different doses of IL-3. The dose-response relationship between GzmB expression and facilitation of lipid mediator formation was identical (ED50: 1-3 ng/mL), while lower doses of IL-3 were sufficient to enhance degranulation (ED50: 0.1-0.3 ng/mL) (Figure 4B). Thus, these data together with our earlier studies on IL-4 and IL-13 expression11,13-15,42 demonstrate a close conditional and temporal relationship between the induction of granzyme B, the facilitation of C5a-induced LTC4 formation, and the promotion of IL-4 and IL-13 production.

Induction of GzmB by cytokines and products of activated mast cells. (A) Effect of different cytokines on the induction of GzmB and on the response of basophils to C5a. Basophils were cultured overnight in medium alone or with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), GM-CSF (50 ng/mL), IL-5 (50 ng/mL), NGF (50 ng/mL), IL-2 (100 U/mL), IFN-α (1000 U/mL), or IFN-γ (1000 U/mL). Intracellular GzmB was analyzed by flow cytometry. The Δ mean fluorescence (mean fluorescence of the specific mAb minus fluorescence of control antibody for each condition) is shown. (Lower panels) Following overnight culture with indicated cytokines, basophils were stimulated with C5a (10 nM) for 30 minutes to induce degranulation. Released (▪) and cell-associated (□) GzmB, LTC4, and histamine release is shown. No histamine or LTC4 release was detected when the stimulation with C5a was omitted (not shown). Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment are shown. Experiments performed with basophils from 3 different donors showed an identical pattern of results and the same order of efficacy of the cytokines. Also note the congruent results for GzmB induction determined by flow cytometry and ELISA that were performed in independent experiments. (B) Relationship between induction of GzmB and “late priming” with different concentrations of IL-3. Basophils were incubated in medium or different concentrations of IL-3. After 24 hours, cells were stimulated with 10 nM C5a for 30 minutes. Released and cell-associated GzmB and histamine and leukotriene formation is shown (mean values of triplicate determinations of a representative experiment out of 3). (C) The products of IgE-activated mast cells induce GzmB in basophils. Western blots of cell extracts of basophils cultured overnight with supernatants of human mast cells (MC supernatants) that have been activated by IgE-receptor cross-linking (a-IgER) or not (buffer) are shown (“Materials and methods”). For comparison, extracts of the same basophil preparation of freshly isolated basophils, or basophils cultured in medium (buffer) or with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), are included in the blot. Where indicated by +, a neutralizing polyclonal goat anti–IL-3 antibody (a-IL-3; 10 μg/mL) was added. An irrelevant control goat IgG had no effect on GzmB expression (data not shown). Tyr694 phosphorylation of Stat5 is shown as another independent indicator for the stimulation of basophils by mast cell–derived IL-3. Total Stat5 levels were identical under all the conditions (data not shown).

Induction of GzmB by cytokines and products of activated mast cells. (A) Effect of different cytokines on the induction of GzmB and on the response of basophils to C5a. Basophils were cultured overnight in medium alone or with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), GM-CSF (50 ng/mL), IL-5 (50 ng/mL), NGF (50 ng/mL), IL-2 (100 U/mL), IFN-α (1000 U/mL), or IFN-γ (1000 U/mL). Intracellular GzmB was analyzed by flow cytometry. The Δ mean fluorescence (mean fluorescence of the specific mAb minus fluorescence of control antibody for each condition) is shown. (Lower panels) Following overnight culture with indicated cytokines, basophils were stimulated with C5a (10 nM) for 30 minutes to induce degranulation. Released (▪) and cell-associated (□) GzmB, LTC4, and histamine release is shown. No histamine or LTC4 release was detected when the stimulation with C5a was omitted (not shown). Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment are shown. Experiments performed with basophils from 3 different donors showed an identical pattern of results and the same order of efficacy of the cytokines. Also note the congruent results for GzmB induction determined by flow cytometry and ELISA that were performed in independent experiments. (B) Relationship between induction of GzmB and “late priming” with different concentrations of IL-3. Basophils were incubated in medium or different concentrations of IL-3. After 24 hours, cells were stimulated with 10 nM C5a for 30 minutes. Released and cell-associated GzmB and histamine and leukotriene formation is shown (mean values of triplicate determinations of a representative experiment out of 3). (C) The products of IgE-activated mast cells induce GzmB in basophils. Western blots of cell extracts of basophils cultured overnight with supernatants of human mast cells (MC supernatants) that have been activated by IgE-receptor cross-linking (a-IgER) or not (buffer) are shown (“Materials and methods”). For comparison, extracts of the same basophil preparation of freshly isolated basophils, or basophils cultured in medium (buffer) or with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), are included in the blot. Where indicated by +, a neutralizing polyclonal goat anti–IL-3 antibody (a-IL-3; 10 μg/mL) was added. An irrelevant control goat IgG had no effect on GzmB expression (data not shown). Tyr694 phosphorylation of Stat5 is shown as another independent indicator for the stimulation of basophils by mast cell–derived IL-3. Total Stat5 levels were identical under all the conditions (data not shown).

In order to mimic the molecular and cellular events of allergic late-phase reactions, basophils were exposed to supernatants of mature human mast cells (MCs) cultured for 24 hours with or without activation by FcϵRIα cross-linking. Similar to IL-3, the products of activated MCs induced the expression GzmB mRNA (induction by 3-4 orders of magnitude after 6 hours) as well as GzmB protein (Figure 4C). MC-induced GzmB expression in basophils could be inhibited by a neutralizing polyclonal anti–IL-3 antibody, indicating that the effect is largely due to MC-derived IL-3 formed in response to IgE receptor activation. Because among the close to 20 cytokines studied, only IL-3 induced sustained Tyr694 phosphorylation of Stat5 in human basophils (S.D. and C.A.D., unpublished findings, October 2005), this parameter was also examined. The enhanced Stat5 phosphorylation in response to the products of activated MCs and its inhibition by IL-3 neutralization further demonstrate the key role of IL-3 in this model of MC-basophil interaction.

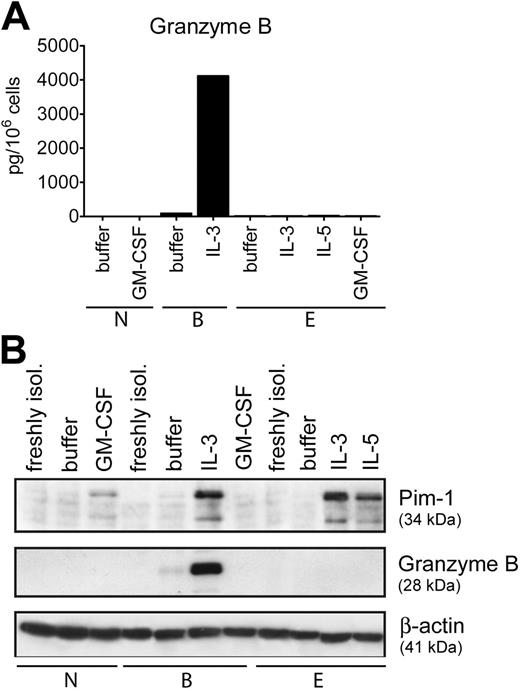

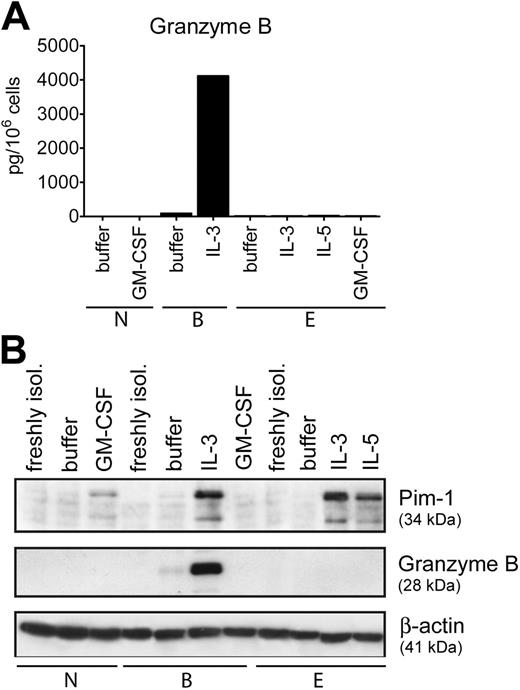

Granulocyte-type–restricted induction of granzyme B

IL-3 belongs to a subgroup of growth factors (IL-3, IL-5, GM-CSF) that share a common receptor beta-chain (CD131) needed for signaling.43,44 Neutrophils express GM-CSF receptors only, while eosinophils express receptors for all 3 cytokines.43 Thus, we examined whether appropriate cytokines are able to induce GzmB expression in other types of granulocytes. In marked contrast to basophils, none of the growth factors stimulated GzmB expression in neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 5). In comparison, a different pattern of expression of another protein, Pim-1, was observed in all types of granulocytes, confirming cellular responsiveness to stimulation (Figure 5B). Pim-1 is a serine/threonine kinase induced by growth/survival factors in hematopoietic cells, and IL-5 and GM-CSF were shown to stimulate Pim-1 mRNA and protein expression in human eosinophils.45,46 The induction of Pim-1 expression by cytokines interacting with CD131 in all granulocytes further underscores the unique ability of basophils to express GzmB, suggesting a cell-specific function for this protein.

NK-like cytotoxicity activity of human basophils

To assess a possible functional role of GzmB, we tested whether basophils can mediate lysis of appropriate target cells. Because basophils express high levels of CD244, we used the B-cell line 721.221 that expresses CD48, the ligand for CD244, as target cells in the cytotoxicity assay.35,36 Figure 6 shows that basophils indeed display NK-like activity toward these target cells, albeit less strongly than NK cells. Basophil-mediated target cell lysis is completely blocked by the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD consistent with a caspase-dependent killing mechanism. Of importance, the cytotoxic activity of basophils is considerably enhanced by IL-3 and can be inhibited by the GzmB-inhibitor Z-IETD, suggesting an involvement of GzmB in the cytolytic activity of IL-3–treated basophils.

Cell-type–restricted expression of GzmB. (A) Purified granulocytes, basophils (B), eosinophils (E), and neutrophils (N) were cultured overnight in medium alone or with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), IL-5 (50 ng/mL), and GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) as indicated. The GzmB content in total cell lysates was determined by specific ELISA. Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment out of 3 are shown. (B) Protein extracts derived from freshly isolated cells or from cells cultured for 24 hours in medium alone or with IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF (all at 50 ng/mL) were analyzed for GzmB and Pim-1 expression. Actin is shown as a loading control. The data shown in panels A and B were from separate experiments with cells from different donors.

Cell-type–restricted expression of GzmB. (A) Purified granulocytes, basophils (B), eosinophils (E), and neutrophils (N) were cultured overnight in medium alone or with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), IL-5 (50 ng/mL), and GM-CSF (50 ng/mL) as indicated. The GzmB content in total cell lysates was determined by specific ELISA. Mean values of triplicates of a representative experiment out of 3 are shown. (B) Protein extracts derived from freshly isolated cells or from cells cultured for 24 hours in medium alone or with IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF (all at 50 ng/mL) were analyzed for GzmB and Pim-1 expression. Actin is shown as a loading control. The data shown in panels A and B were from separate experiments with cells from different donors.

Release of granzyme B in vivo after experimental allergen challenge of asthmatic patients

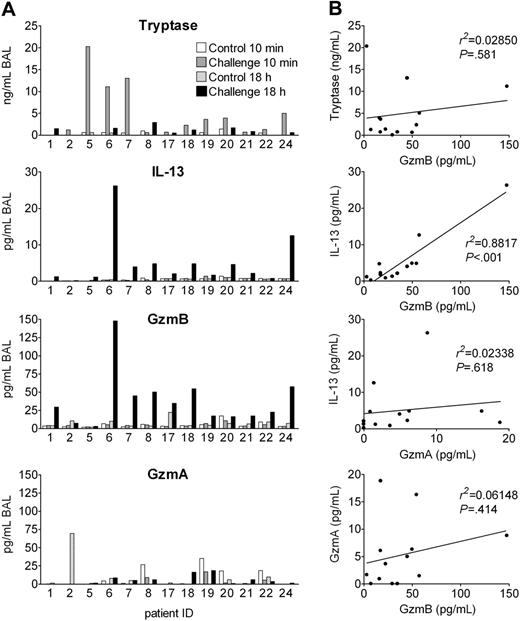

In humans, basophils rapidly infiltrate affected tissues and may then be activated by endogenous cell-derived and humoral agonists to release inflammatory mediators and cytokines. If basophils are activated to express and release GzmB in vivo, one would expect GzmB release within the allergic late-phase reaction (LPR). Segmental allergen challenge is a particularly elegant model, since only 1 lung segment is challenged with allergen, while a control segment is challenged with vehicle.28 Thus, each patient serves as his own control. We measured GzmB levels in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids obtained 10 minutes and 18 hours after segmental challenge with solvent and allergen of 13 patients with allergic asthma. Tryptase was measured as an MC degranulation marker and GzmA as a marker of cytotoxic granules from lymphocytes. IL-13 levels were determined, because IL-13 is regarded as a key cytokine in the pathogenesis of asthma,47 and because both mediators are induced in basophils in a similar manner and within the same time frame. Figure 7A demonstrates that, indeed, GzmB and IL-13 levels, in contrast to GzmA, were increased in BAL fluids of challenged segments after 18 hours in almost all patients, but not in the controls. In contrast to all other parameters, tryptase was increased 10 minutes after allergen exposure, indicating that mast cells do not release preformed GzmB. Mean GzmB concentrations were about 7 times higher than those of IL-13 and the increase of both mediators was highly significant (P < .001 between groups by ANOVA; Figure S2). Particularly striking for clinical human samples is the excellent correlation between IL-13 and GzmB levels found 18 hours after challenge, in contrast to the lack of significant correlations between IL-13 and GzmA, between GzmB and GzmA, or between immediate tryptase and late GzmB levels (Figure 7B). The increase of IL-13 and GzmB was less consistent and pronounced 42 hours and was absent 162 hours after allergen provocation as examined in 6 and 4 patients, respectively (Figure S3). Thus, IL-13 and GzmB appear in the LPR in a highly related manner and within the same time frame.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that IL-3 can qualitatively alter the composition of granule constituents of mature human blood basophils by inducing de novo expression of GzmB. More preliminary data indicate that the expression of some other granule proteins may also change depending on the cytokine milieu, a further sign of the remarkable plasticity of granule protein expression of this blood granulocyte type. Thus, the notion that the granule components of blood granulocytes have a fixed cell-type–dependent composition must be revised, at least for basophil granulocytes. The induction of GzmB in basophils is particularly surprising because, within the immune system, GzmB is thought to be restricted to the lymphoid lineage.33,48,49 To date, there has been no indication that myeloid cells may express GzmB, with the exception of a report claiming the presence of GzmB and perforin in human blood neutrophils.37 This view has been refuted by several groups50-52 and is also in conflict with our data. Even eosinophils, cells closely related to basophils, do not express GzmB constitutively or after stimulation with IL-3, IL-5, or GM-CSF, demonstrating the importance of the cellular background and indicating that some gene(s) expressed by basophils are needed for IL-3–induced GzmB expression.

Functional experiments with different triggers conclusively demonstrate that GzmB is sorted, at least in part, to a granule compartment that can be mobilized in a way similar to histamine, although the extent of exocytosis of these mediators does not fully overlap. Using experimental conditions resulting in the expression of high levels of IL-4 and IL-13 together with a prolonged wave of LTC4 formation, we found that the combination of C5a and IL-3 leads to a slow secretion of GzmB in parallel with its formation. C5a neither directly induces GzmB nor alters the amounts or kinetics of IL-3–induced GzmB production. Thus, the regulation of GzmB expression in basophils differs from that of IL-4/IL-13, which need both signals for optimal induction, and also from that of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, which is induced by C5a alone.53

Cytotoxic activity of human peripheral blood basophils. (A) Nonstimulated basophils, IL-3–stimulated (50 ng/mL, 40 hours) basophils, and NK-92 cells were analyzed in a direct killing assay against [51Cr]-labeled B-LCL 721.221 cells. Effector cells were incubated for 10 hours with target cells at E/T (effector-target) ratios of 15:1, 30:1, and 60:1. (B) IL-3–stimulated basophils and NK-92 cells were incubated with B-LCL 721.221 target cells in the absence or presence of Z-VAD-fmk (50 μM, pan-caspase inhibitor) or Z-IETD-fmk (50 μM, GzmB inhibitor) for 10 hours at an E/T ratio of 60:1. Cytotoxicity was estimated as described in “Materials and methods.” The data shown (mean of duplicates) are representative of 3 independent experiments. The enhancement of the cytotoxic activity of basophils by IL-3 and its inhibition by the pan-caspase and GzmB inhibitors were statistically significant (P > .01 for all conditions as determined by the paired Student t test).

Cytotoxic activity of human peripheral blood basophils. (A) Nonstimulated basophils, IL-3–stimulated (50 ng/mL, 40 hours) basophils, and NK-92 cells were analyzed in a direct killing assay against [51Cr]-labeled B-LCL 721.221 cells. Effector cells were incubated for 10 hours with target cells at E/T (effector-target) ratios of 15:1, 30:1, and 60:1. (B) IL-3–stimulated basophils and NK-92 cells were incubated with B-LCL 721.221 target cells in the absence or presence of Z-VAD-fmk (50 μM, pan-caspase inhibitor) or Z-IETD-fmk (50 μM, GzmB inhibitor) for 10 hours at an E/T ratio of 60:1. Cytotoxicity was estimated as described in “Materials and methods.” The data shown (mean of duplicates) are representative of 3 independent experiments. The enhancement of the cytotoxic activity of basophils by IL-3 and its inhibition by the pan-caspase and GzmB inhibitors were statistically significant (P > .01 for all conditions as determined by the paired Student t test).

Granzyme B is released in experimental allergic late-phase reaction in asthma patients. Segmental allergen provocation was performed in 13 patients suffering from allergic asthma. Separate lung segments were challenged with saline or antigen, and BAL was performed in the same session 10 minutes later. Eighteen hours after challenge, a second bronchoscopy was performed and BAL was repeated for recovery of inflammatory mediators. (A) Tryptase, IL-13, GzmB, and GzmA levels in the BAL fluids of each of 13 patients analyzed are shown. (B) Shown are the correlations between tryptase levels of the challenged site in the immediate response (10 minutes) and GzmB levels in the late-phase reactions (18 hours) as well as correlations between IL-13, GzmB, and GzmA levels in BAL fluids of the challenged segment 18 hours after allergen provocation.

Granzyme B is released in experimental allergic late-phase reaction in asthma patients. Segmental allergen provocation was performed in 13 patients suffering from allergic asthma. Separate lung segments were challenged with saline or antigen, and BAL was performed in the same session 10 minutes later. Eighteen hours after challenge, a second bronchoscopy was performed and BAL was repeated for recovery of inflammatory mediators. (A) Tryptase, IL-13, GzmB, and GzmA levels in the BAL fluids of each of 13 patients analyzed are shown. (B) Shown are the correlations between tryptase levels of the challenged site in the immediate response (10 minutes) and GzmB levels in the late-phase reactions (18 hours) as well as correlations between IL-13, GzmB, and GzmA levels in BAL fluids of the challenged segment 18 hours after allergen provocation.

In allergic late-phase reactions, infiltrating basophils must be activated by endogenous agonists, although activation by allergen may also play a role in chronic disease. Our previous and the present studies, therefore, focused on the effects of endogenous stimuli either alone or in combination. Particularly striking is the close correlation between leukotriene formation, IL-4 and IL-13 expression, and the de novo induction of GzmB, with regard to both the time frame and the efficacy of cytokines regulating these important functions in basophils. The most efficient cytokine inducing GzmB together with other phenotypic and functional alterations is IL-3.30-32 An identical concentration range of IL-3 induces GzmB expression and the persistent facilitation of LTC4 formation. When the effect of different cytokines was compared, we observed an identical order of efficacy. The same is true for the regulation of IL-4 and IL-13 expression, as shown earlier.13-15,42 The fact that supernatants of IgE-receptor–activated human MCs can induce GzmB expression in blood basophils further supports the pathophysiologic relevance of our observations. Although this induction of GzmB is largely due to MC-derived IL-3, other mast cell cytokines may also contribute.

In agreement with these in vitro findings and further supporting a role of basophils in human asthma, we found a highly correlated increase of IL-13 and GzmB levels in the BAL fluids of the challenged lung segment of patients with allergic asthma 18 hours after provocation. Thus, GzmB must be considered as a potential mediator of asthma, apart from its well-established role in granule-mediated cytotoxicity of lymphocytes. There is increasing evidence that IL-13 is a key cytokine in promoting the clinical symptoms of asthma, such as bronchial hyperreactivity and mucus secretion. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that the level of IL-13 after allergen provocation is an indicator for the severity of the local LPR. The excellent correlation between IL-13 and GzmB in the challenged segments at 18 hours together with the lack of a significant correlation between these GzmB levels and tryptase released in the immediate reaction indicates that GzmB levels reflect the intensity of the LPR. Of importance, GzmB was released without an increase of GzmA during this time point of the LPR, data consistent with a nonlymphoid source of this protease since cytotoxic lymphocytes (CLs) express even larger amounts of GzmA than GzmB. Indeed, in BAL fluids of patients with CD8+ T-cell–mediated hypersensitivity pneumonitis, higher levels of GzmA than GzmB are found.34 Furthermore, human NK-92 cells express similar amounts of GzmB as stimulated basophils, but about 2 to 3 times more GzmA. Finally, although T cells may selectively express GzmB under some circumstances (in vitro stimulation with anti-CD3 anti-CD46),54 we never observed even a minor population of GzmA–/GzmB+ cells in the T-cell compartment in vivo, in contrast to GzmA+/GzmB+ and GzmA+/GzmB– subpopulations.48 Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo data strongly suggest that basophils are a source of GzmB found at sites of allergic inflammation, although one cannot exclude a contribution of other cells selectively expressing GzmB, such as plasmacytoid dendritic cells.49 Furthermore, our study does not exclude a (most probably minor) contribution of lymphocyte-derived GzmB, particularly at later time points after challenge when GzmB levels are decreasing and lymphocyte accumulation becomes more prominent, since a small proportion of BAL lymphocytes have been shown to express GzmB.55 It should be noted, however, that the percentage of granzyme-expressing lymphocytes does not change 42 hours after allergen challenge.55

The function of GzmB has been thoroughly studied for its involvement in granule-mediated cytotoxicity. In CLs, perforin is needed to deliver GzmB into the cytosol thereby inducing apoptosis of target cells.33 In order to find a possible functional role of GzmB induction in basophils, we tested whether basophils may be able to kill appropriate target cells, although they are not regarded as killer cells and do not express detectable perforin. Surprisingly, we find an NK-like activity that is enhanced by IL-3 and diminished by GzmB inhibition, challenging this dogma and indicating a perforin-independent unknown killing mechanism that needs further investigation. It should be noted that membrane-active bacterial toxins and adenovirus can substitute for perforin,56 and it is thus not impossible that a myeloid granule component present in basophils, but not lymphocytes, may similarly substitute perforin. Furthermore, a perforin-independent GzmB-dependent cytotoxicity has been very recently suggested for murine T-regulatory cells.57 However, in asthma an extracellular role of GzmB is much more likely, since GzmB is readily released by basophils and since this protease is less inhibited by antiproteases in bodily fluids34 than other cell-derived enzymes. Furthermore, outside the immune system, GzmB is produced in the absence of perforin by cells of the reproductive system, further indicating bioactivity of GzmB unrelated to target-cell lysis.58 Unfortunately, and in contrast to intracellular proteins, possible extracellular GzmB substrates are only beginning to be investigated. Most relevant for this hypothesis is a very recent report demonstrating extracellular matrix remodeling by GzmB with induction of death in adherent cells by cell detachment (anoikis).59 Thus, GzmB released in asthma could play a role in tissue remodeling.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that IL-3 not only alters the function of mature blood basophils but also leads to a qualitative change of the composition of their granules by de novo expression of GzmB. There is a close conditional and temporal correlation between GzmB and IL-13 secretion by basophils in vitro and during the allergic late-phase reaction in patients with asthma in vivo, indicating an unsuspected novel role of basophil-derived GzmB in the pathogenesis of allergic inflammation and possibly other Th2-type immune responses, such as the defense against helminth parasites.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 27, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010348.

Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant 3200-063550 and 3200B0-105843 (C.A.D.), by the Stiftung 3R (S.D.), and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Vi 193/3-1 (J.C.V.).

C.M.T., N.S., and S.D. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments; C.E.H. contributed essential analytic tools; W.L., P.J., and J.C.V. provided BAL samples and clinical data of asthmatic patients; and C.A.D. contributed to the design and presentation of the study.

C.M.T., N.S., and S.D. contributed equally to this work.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We express our sincere thanks to Philippe Demougin, Nicolas Leupin, Michel Bellis, and Rodoljub Pavlovic for help and technical assistance.

![Figure 6. Cytotoxic activity of human peripheral blood basophils. (A) Nonstimulated basophils, IL-3–stimulated (50 ng/mL, 40 hours) basophils, and NK-92 cells were analyzed in a direct killing assay against [51Cr]-labeled B-LCL 721.221 cells. Effector cells were incubated for 10 hours with target cells at E/T (effector-target) ratios of 15:1, 30:1, and 60:1. (B) IL-3–stimulated basophils and NK-92 cells were incubated with B-LCL 721.221 target cells in the absence or presence of Z-VAD-fmk (50 μM, pan-caspase inhibitor) or Z-IETD-fmk (50 μM, GzmB inhibitor) for 10 hours at an E/T ratio of 60:1. Cytotoxicity was estimated as described in “Materials and methods.” The data shown (mean of duplicates) are representative of 3 independent experiments. The enhancement of the cytotoxic activity of basophils by IL-3 and its inhibition by the pan-caspase and GzmB inhibitors were statistically significant (P > .01 for all conditions as determined by the paired Student t test).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/108/7/10.1182_blood-2006-03-010348/4/m_zh80190601940006.jpeg?Expires=1769233076&Signature=B7xSrLOHijFdrCXqq9xJnkDnXvpB8jIcrmYoa-5HNJGdQGTnLUMZd9XLAZ1gxKwPwTucfeVzALWj4fPCkja9iGLjb5rX3cFU7LnPPzC1LBv8rM3Q~bkIy-Yiov2ISEA-YcBBS1bceV3hqSkM3xijJ-lZTbihc3NkOYbswNMzkIv8Q~iWYGZagf4HwQEjLno3cSeQ4u-viu5AX-KQo2~rF-8kiW8in343HDKl5IYDB76JRBzg5VUpZ8z05VEOW5-aDUkGCo~~kIZo~CkBEDGsS8M94yYcMALX1LOjqbbwJndJa91aHVHUdWUQdiToERxnH4y~7qcQBB-TqdjBHdnftg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Cytotoxic activity of human peripheral blood basophils. (A) Nonstimulated basophils, IL-3–stimulated (50 ng/mL, 40 hours) basophils, and NK-92 cells were analyzed in a direct killing assay against [51Cr]-labeled B-LCL 721.221 cells. Effector cells were incubated for 10 hours with target cells at E/T (effector-target) ratios of 15:1, 30:1, and 60:1. (B) IL-3–stimulated basophils and NK-92 cells were incubated with B-LCL 721.221 target cells in the absence or presence of Z-VAD-fmk (50 μM, pan-caspase inhibitor) or Z-IETD-fmk (50 μM, GzmB inhibitor) for 10 hours at an E/T ratio of 60:1. Cytotoxicity was estimated as described in “Materials and methods.” The data shown (mean of duplicates) are representative of 3 independent experiments. The enhancement of the cytotoxic activity of basophils by IL-3 and its inhibition by the pan-caspase and GzmB inhibitors were statistically significant (P > .01 for all conditions as determined by the paired Student t test).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/108/7/10.1182_blood-2006-03-010348/4/m_zh80190601940006.jpeg?Expires=1769233077&Signature=ZCt4v9qfLTCge~jitjvJB1Hp4c2PsLxK8ZPxVwLM1Oycxk~mZVmsQ7wUYnnG-q3jclFiNoOEERqqrzb1WyT7LSh0cgfiRhxjZBvq18O5XUglsh3ArwpFRxxmzA6OPeCljWCWhRR3zKew7PQ8rD~hdlbOpODvA-1B69OG~UP0hN7nqYEITyo9S3gSQtP5Y0oTTYYEhU11zUuC1GvSeWXsffNJbxoxqIlOlXvGVt6WZARTy8H50~ag35c6s3LVKGq8hfbi1TfeNU4sDd8plRPli8bKJZUgeDApYs2ur2iY2Nli9QT6swQDIGuy7XW1akIwJffkgowOcSh1tjd6129KOg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)