Abstract

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are critical for the initiation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), although the responsible APC subset and molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Because dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent APCs and the NF-kB/Rel family member RelB is associated with DC maturation and potent APC function, we examined their role in GVHD. Within 4 hours of total body irradiation, RelB nuclear translocation was increased and restricted to CD11chi DCs within the host APC compartment. Furthermore, the transient depletion of CD11chi donor DCs that reconstitute in the second week after transplantation resulted in a transient decrease in GVHD severity. By using RelB−/− bone marrow chimeras as transplant recipients or RelB−/− donor bone marrow, we demonstrate that the induction and maintenance of GVHD is critically dependent on this transcription factor within both host and donor APCs. Critically, RelB within APCs was required for the expansion of donor helper T cell type 1 (Th1) effectors and subsequent alloreactivity, but not the peripheral expansion or function of donor FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. These data suggest that the targeted inhibition of nuclear RelB translocation within APCs represents an attractive therapeutic strategy to dissociate effector and regulatory T-cell function in settings of Th1-mediated tissue injury.

Introduction

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is the definitive curative therapy for the majority of hematologic malignancies and severe immunodeficiencies. The major complication of allogeneic BMT remains graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in which the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver are preferentially damaged by the transplanted donor immune system. The therapeutic potential of BMT relates to the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect, which eradicates host malignancy after BMT and is mediated by donor T and natural killer cells.1 GVHD occurs in the majority (50%-70%) of recipients and is largely responsible for the high rate of mortality associated with allogeneic BMT. There is thus a pressing need for new treatment approaches to both prevent and treat GVHD, ideally without inhibiting GVL.

The complex interactions resulting in the generation of T-cell–mediated alloimmune responses depend on antigen presentation, cognate interactions between donor T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and the concomitant production of soluble and membrane-bound costimulatory molecules by APCs and T cells (reviewed in Morris et al2 ). The initiation of GVHD absolutely depends on the presence of mature donor T cells in the graft.2 Thus, although TLR signaling undoubtedly contributes to the activation of APCs early after transplantation,3 it is likely that donor T cells provide the most critical signal. In this regard, the CD40-CD40L pathway appears to be of major importance, as demonstrated by the induction of tolerance following disruption of this receptor-ligand interaction.4 The subsequent molecular mechanisms controlling APC function in tolerance and immunity are poorly defined. The NF-kB/Rel family of proteins include 5 subunits: c-Rel, RelA, RelB, NF-kB1, and NF-kB2, which form homodimers or heterodimers. At steady state, most of these proteins are inactive within the cytoplasm, bound by inhibitory IkB proteins. Activation by the classical pathway within a broad range of cells (including APCs and T cells) occurs as a result of a variety of membrane signals, including TNF, IL-1, and Toll receptors, that allow nuclear import of c-Rel and RelA heterodimers with subsequent transcriptional activation of inflammatory proteins. Activation by the alternative pathway within APCs is the result of lymphocyte interactions and signaling through the lymphotoxin-β receptor, BAFF receptor or CD40, resulting in nuclear import of p52/RelB heterodimers and transcriptional activation of characterized and uncharacterized proteins that result in maturation and antigen-presenting activity within professional APCs.5–7

Because APCs are known to be critical for the initiation and maintenance of GVHD8,9 and their activation occurs rapidly after transplantation,10 we hypothesized that maintaining host APCs in a state of RelB inactivity during conditioning would promote the induction of peripheral tolerance after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT). We found that the lack of RelB within either host or donor APCs limited the ability of these cells to initiate and maintain GVHD, respectively. Strikingly, this was due to the failure of donor helper T cell type 1 (Th1) expansion after transplantation.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b, CD45.2+), B6 PTPRCA Ly-5a (H-2b, CD45.1+), B6D2F1 (H-2b/d, CD45.2+), and BALB/c (H-2d, CD45.2+) mice were purchased from the Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Australia). RelB−/− (B6, H-2b, CD45.2+) mice11 were originally provided by L. Wu (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia), and selected heterozygotes were bred in the animal facility at Herston (University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia). CD11c-DTR-GFP and “MacGreen” (c-fms/EGFP) transgenic mice on a B6 background were provided by Mark Smyth (Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Melbourne, Australia) and David Hume (University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia), respectively. Mice were housed in sterilized microisolator cages and received normal chow and autoclaved drinking water which was acidified for the first 2 weeks after BMT. Bone marrow chimeras (BMCs) were generated by injecting 5 × 106 T-cell–depleted (TCD) BM cells from WT or RelB−/− donors into irradiated B6 PTPRCA recipients (1000 cGy, split dose separated by 3 hours from a 137Cs source at 108 cGy/min). BMCs were then phenotyped or used as transplant recipients 3 to 4 months later as previously described.8 In some experiments, luciferase-transfected P815 host-type (H-2d) leukemia cells were administered to transplant recipients 14 days after BMT, and the development of leukemia was monitored by biophotonic imaging as previously described.12

mAbs

The following mAbs were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA): FITC-conjugated I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), CD45.1 (A20), and IgG2a isotype control; PE-conjugated CD4 (RM4-5), CD8a (53-6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), CD45.2 (104), and IgG2b isotype control; PE-Cy5–conjugated CD8, CD4, and IgG2b isotype control; Alexa647-conjugated anti-FoxP3 and isotype control; allophycocyanin-conjugated CD11c (N418) and IgG2b isotype control. FITC-conjugated CD25 (7D4) and PE-conjugated CD40 (3/23), CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), CD62L (MEL14), and I-A/I-E (2G9) were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Purified anti-RelB (C-19) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Biotinylated anti–rabbit immunoglobulins and streptavidin-HRP were purchased from DakoCytomation (Ft Collins, CO). PE-conjugated PDCA-1 was purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). FITC-conjugated CD11c (HL3) and purified mAb against CD3 (KT3), CD19 (HB305), CD25 (PC61), rat IgG1 isotype control (MAC-49), Gr1 (RB6-8C5), Thy1.2 (HO-13-4), CD62L (MEL14), Ter119, and FcγR II/III (2.4G2) were produced in house.

Cell preparation

DC purification was undertaken as previously described.13 Briefly, low-density cells were enriched from digested spleen by Optiprep density gradient centrifugation. For culture experiments, highly purified DC populations (> 98%) were obtained from the density gradient–enriched APC fraction by fluorescence-activated cell sorting of CD11chi cells (MoFlo; DakoCytomation). For MLC, splenic CD3+ T cells were purified to greater than 90% by depleting B cells (B220, CD19), monocytes (CD11b), granulocytes (Gr-1), and erythroid cells (Ter119) using magnetic bead depletion. In some experiments, antibody to CD8a was added to this cocktail to purify CD4 T cells for transplantation. Naive CD4+ T cells were purified from spleen for in vitro assays by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of the CD4+CD62L+ population.

Phenotypic analysis

For analysis of cell-surface molecules, cells were incubated with mAb as per the manufacturer's instructions or at 5 to 20 μg/mL in 2% FCS in PBS, for 20 to 60 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed in 2% FCS in PBS. Biotinylated mAbs were detected with the appropriate conjugated streptavidin detection reagents diluted in 2% FCS in PBS and analyzed on a FACS Calibur cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). In some experiments, 7AAD (1 μg/mL) was added in the final wash to identify dead cells. For FoxP3 detection, following surface labeling, cells were fixed and permeabilized using “Fix & Perm” (BioLegend), followed by incubation with Alexa647-conjugated FoxP3 mAb (BioLegend).

TBI and RelB expression

For immunohistochemical detection of RelB, spleens were harvested from control B6 mice or 24 hours after total body irradiation (TBI; 1100 cGy using a 137Cs source at 108 cGy/min), APCs were enriched by density gradient centrifugation, and cytospins were prepared. Slides were fixed in paraformaldehyde and stained for RelB using immunoperoxidase and diaminobenzidine staining as previously described.14 For quantification of nuclear RelB, nuclear protein extracts from sort-purified cell populations were prepared as previously described,15 and protein was estimated using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit (Hercules, CA). RelB DNA binding was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a Mercury Transfactor NFkB kit (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). Briefly, 50 μg nuclear protein was bound to wells coated with NF-kB consensus oligonucleotide, incubated with anti-RelB followed by anti–rabbit HRP-conjugated Ig, and then detected by measuring color development of tetramethylbenzidine at 650 nm using a Multiskan plate reader (Labsystems, Chicago, IL).

Microscopy

Confocal images of split mouse ear pinnae were acquired at various times after transplantation using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal and Leica upright Model DMRE microscope (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, GmbH) with 63×/1.32 HCX PL APO objectives at room temperature using 488 nm laser excitation. Imaging used Leica Confocal Software (LCS) Version 2.61 build 1537 acquisition software. Immunohistochemistry images were acquired on an Olympus BX41 microscope and Olympus DP12 camera (Tokyo, Japan) using a 10× ocular objective and 100×/1.25 oil objective at room temperature.

Cell culture and cytokine analysis

Sort-purified CD11chi DCs were cultured for 18 to 24 hours at 106 cells/mL in 10% FCS/IMDM (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) supplemented with GM-CSF, IL-4 (each at 100 ng/mL), and IFNγ (20 ng/mL) with or without anti-CD40 (FGK-45; 100 μg/mL). Tissue culture supernatants were stored at −70°C for subsequent cytokine analysis. For MLCs, 105 magnetic bead–purified Balb/c T cells were cultured for 5 days with varying numbers of sort-purified CD11chi DCs. [3H]-thymidine (1 μCi [0.037 MBq]/well) was added on day 4, and proliferation was determined 18 hours later using a Betaplate Reader (Wallac, Turku, Finland). For Treg suppression assays, 105 magnetic bead–purified CD4+ Balb/c T cells were cultured with 104 sort-purified CD11chi Balb/c DCs in the presence of anti-CD3 (2C11; 1 μg/mL) and varying numbers of sort-purified CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. [3H]-thymidine (1 μCi [0.037 MBq]/well) was added on day 3, and proliferation was determined 18 hours later. All cytokine analysis used CBA inflammation or Th1/Th2 kits (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) as per the manufacturer's recommended protocols.

Bone marrow transplantation

Two well-established murine transplantation models were used, and mice received transplants according to a standard protocol as previously described.12,16–18 To study the effect of RelB within recipient APCs, BMCs received 950 cGy (split dose separated by 3 hours on day 0) and were transplanted with 5 × 106 bone marrow and 3 × 106 purified splenic T cells from Balb/c (allogeneic) or B6 (syngeneic) donors. For donor Treg depletion studies, Balb/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500 μg anti-CD25 mAb (PC61) or control mAb (rat IgG1 isotype control MAC49) on day −4 prior to transplantation. BMCs received BM from PC61-treated donors supplemented with 3 × 106 purified lymph node (LN) T cells from control mAb or PC61-treated donors. To study the effect of RelB within donor APCs on GVHD, B6D2F1 mice received 1100 cGy on day 0 and were given transplants of 5 × 106 bone marrow cells from WT or RelB KO mice with or without 5 × 105 purified splenic T cells. Animals were monitored daily thereafter. For the transient depletion of DCs after transplantation, irradiated B6D2F1 mice were given transplants of 5 × 106 BM cells from CD11c-DTR-GFP Tg mice with or without 5 × 105 purified splenic T cells. Recipients received diptheria toxin (DT) (100 ng intraperitoneally) at 14, 18, and 23 days after BMT.

Assessment of GVHD

The degree of systemic GVHD was assessed by a scoring system that sums changes in 5 clinical parameters: weight loss, posture (hunching), activity, fur texture, and skin integrity (maximum index = 10).19 Animals with severe clinical GVHD (scores ≥ 6) were killed according to ethical guidelines, and the day of death was deemed to be the following day, as previously described.12,16,17,20

Statistics

Survival curves were plotted using Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared by log-rank analysis. The Mann Whitney U test was used for the statistical analysis of cytokine data and clinical scores. P less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

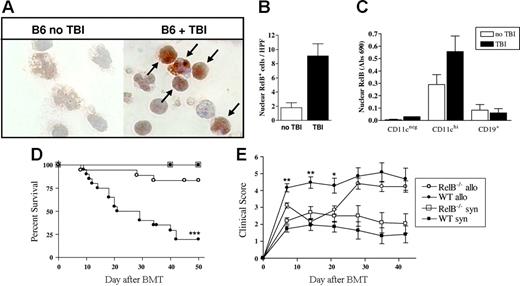

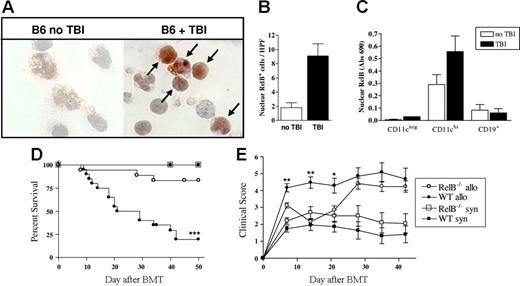

TBI increases RelB expression and promotes nuclear translocation

In initial experiments, we examined the effect of TBI on RelB expression by host APCs. RelB expression was increased 4- to 5-fold in APCs enriched from mice 18 hours after TBI relative to naive mice (Figure 1A-B). When APC subsets were sorted by FACS from naive mice and those that had received TBI 4 hours earlier, nuclear RelB was present in DCs but not B cells or other CD11cneg populations, and this was further enhanced by TBI (Figure 1C). This increase in nuclear RelB was associated with an increase in DC costimulatory molecule expression (data not shown), as previously described.10

TBI increases nuclear RelB translocation in CD11chi DCs and is necessary for the full development of GVHD. (A) Mice were subjected to TBI, and 24 hours later APCs were enriched from spleens of control or irradiated mice. Cytospins were prepared with 105 cells/slide, fixed, and stained for RelB using an immunoperoxidase technique. RelB is stained with diaminobenzidine (brown), and the nucleus is counterstained with hematoxylin (blue) at magnification ×1000. (B) Nuclear RelB-positive cells were enumerated (arrows in panel A), with a minimum of 10 high-power fields counted per slide. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (C) Spleens were harvested from B6 mice before or 4 hours after TBI, and CD19+, CD11cneg, and CD11chi populations were sort purified. Nuclear protein was extracted, and RelB DNA binding was detected by ELISA as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of duplicate samples and representative of 2 similar experiments. (D) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Irradiated WT or RelB−/− BMCs were transplanted with BM and T cells from Balb/c (allo; WT n = 20, RelB−/− n = 18) or B6 donors (syn; WT n = 11, RelB−/− n = 10) as described in “Materials and methods.” ***P < .0001, WT allo versus RelB−/− allo. (E) GVHD clinical scores were determined weekly as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. **P < .01 and *P < .05, WT allo versus RelB−/− allo. Data were combined from 2 replicate experiments.

TBI increases nuclear RelB translocation in CD11chi DCs and is necessary for the full development of GVHD. (A) Mice were subjected to TBI, and 24 hours later APCs were enriched from spleens of control or irradiated mice. Cytospins were prepared with 105 cells/slide, fixed, and stained for RelB using an immunoperoxidase technique. RelB is stained with diaminobenzidine (brown), and the nucleus is counterstained with hematoxylin (blue) at magnification ×1000. (B) Nuclear RelB-positive cells were enumerated (arrows in panel A), with a minimum of 10 high-power fields counted per slide. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (C) Spleens were harvested from B6 mice before or 4 hours after TBI, and CD19+, CD11cneg, and CD11chi populations were sort purified. Nuclear protein was extracted, and RelB DNA binding was detected by ELISA as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of duplicate samples and representative of 2 similar experiments. (D) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Irradiated WT or RelB−/− BMCs were transplanted with BM and T cells from Balb/c (allo; WT n = 20, RelB−/− n = 18) or B6 donors (syn; WT n = 11, RelB−/− n = 10) as described in “Materials and methods.” ***P < .0001, WT allo versus RelB−/− allo. (E) GVHD clinical scores were determined weekly as described in “Materials and methods.” Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. **P < .01 and *P < .05, WT allo versus RelB−/− allo. Data were combined from 2 replicate experiments.

GVHD is attenuated in RelB−/− bone marrow chimeras

RelB−/− mice exhibit impaired development of lymphoid organs, multiorgan inflammation, and splenomegaly and have a reduced lifespan. To overcome this phenotype and to restrict the RelB deficiency to hematopoietic tissues, we generated bone marrow chimeras (BMCs) for use as subsequent transplant recipients. We then examined whether the increased expression of RelB in residual host APCs after irradiation impacted on GVHD outcomes. We used a MHC mismatched BMT model of acute GVHD (Balb/c → B6) in which WT or RelB−/− BMCs were used as recipients. As expected, 100% of the WT and RelB−/− BMC recipients that received syngeneic grafts survived. In contrast, by day 50, the majority (80%) of WT BMC recipients died with characteristic features of GVHD (weight loss, hunching, fur ruffling, etc). The RelB−/− BMC recipients of allogeneic grafts had significantly improved survival compared with the WT BMC recipients (83% versus 20%, P < .001) (Figure 1D). In addition, for the first 3 weeks after BMT, the GVHD clinical scores indicated a significant reduction in disease severity in the RelB−/− BMC recipients compared with WT BMC recipients (P < .01). Subsequently, however, the clinical scores for the RelB−/− BMC recipients increased and were equivalent to those of the WT BMC recipients (Figure 1E).

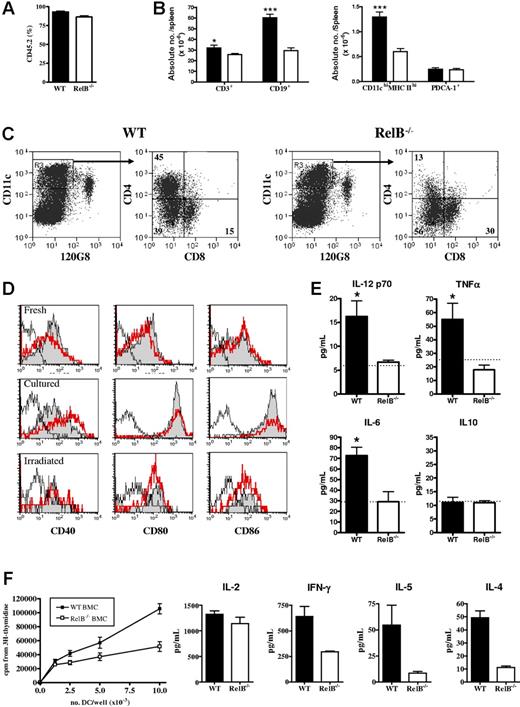

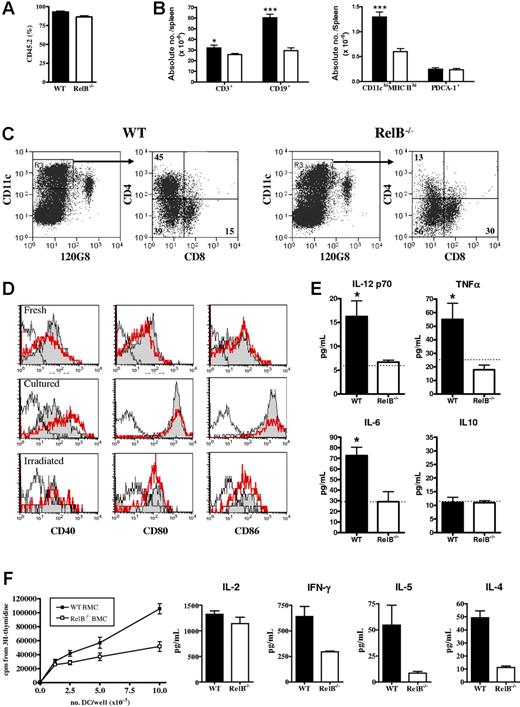

Altered conventional dendritic cell expansion and function in RelB−/− BMCs

Flow cytometric examination of spleens from BMCs 4 to 6 months after generation revealed equivalent proportions of engraftment, although overall spleen size was smaller in the RelB BMCs, predominantly because of diminished numbers of CD19+ B cells (Figure 2A-B). Total splenic PDCA-1+ (plasmacytoid DC) numbers were similar in WT or RelB−/− BMCs; however, the number of conventional CD11chi dendritic cells (cDCs) was significantly decreased in the RelB−/− BMCs (Figure 2B), reflecting an impaired development of the CD4+ subset (Figure 2C). Freshly purified CD11chi cDCs from WT or RelB−/− BMCs expressed equivalent levels of CD40, CD80, and CD86, which were spontaneously up-regulated following overnight culture or following TBI (Figure 2D). Interestingly, CD40 was consistently expressed at a higher level on RelB−/− cDCs following culture (Figure 2D). The addition of LPS or anti-CD40 to cultures had no additional effect on cell-surface costimulatory molecule expression (data not shown). In contrast, although CD40 ligation induced IL-12, IL-6, and TNFα from WT cDCs, those from RelB−/− BMCs failed to respond (Figure 2E). Finally, CD11chi cDCs from RelB−/− BMCs induced lower proliferation and cytokine production in naive (ie, CD62L+) CD4 T cells than DCs from WT BMCs both before (Figure 2F) and after TBI (data not shown). Thus, APCs within RelB−/− BMCs are quantitatively and qualitatively different from those in WT BMCs.

Reconstitution and function of DCs in WT and RelB−/− bone marrow chimeras. Splenocytes from WT or RelB−/− BMCs were examined by flow cytometry for engraftment and cell subset enumeration by staining with (A) CD45.1-FITC, CD45.2-PE, and 7AAD and (B) CD19-FITC, CD3-PE, and 7AAD or I-A/I-E–FITC, PDCA-1–PE, 7AAD, and CD11c-allophycocyanin. Results represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. (C) The density gradient–enriched APC fraction was stained with 120G8-FITC, CD11c-allophycocyanin, and 7AAD; CD11chi 120G8neg DCs were sorted and restained with CD8-FITC and CD4-PE. Numbers in quadrants indicate the frequency of each DC subset. Results are representative of 5 such analyses. (D) Costimulatory molecule expression by freshly sorted or cultured (without anti-CD40 mAb) sort-purified CD11chi DCs from naive (fresh and cultured) or irradiated (irradiated) WT (gray fill) or RelB−/− (thick line) BMCs. Isotype control is shown as a fine line. (E) Cytokine levels in tissue culture supernatants from CD11chi DCs from WT or RelB−/− BMCs cultured with anti-CD40. The dotted line in each histogram represents the cytokine concentration in supernatants of RelB−/− BMC DCs cultured without anti-CD40 which were equivalent to levels from unstimulated WT BMC DCs. Results represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. (F) Sort-purified (H-2b) WT and RelB−/− BMC CD11chi DCs were used to stimulate naive (H-2d) CD4+ T cells in allogeneic MLCs. Proliferation and cytokine content of day 4 culture supernatants were measured as described in “Materials and methods.”

Reconstitution and function of DCs in WT and RelB−/− bone marrow chimeras. Splenocytes from WT or RelB−/− BMCs were examined by flow cytometry for engraftment and cell subset enumeration by staining with (A) CD45.1-FITC, CD45.2-PE, and 7AAD and (B) CD19-FITC, CD3-PE, and 7AAD or I-A/I-E–FITC, PDCA-1–PE, 7AAD, and CD11c-allophycocyanin. Results represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. (C) The density gradient–enriched APC fraction was stained with 120G8-FITC, CD11c-allophycocyanin, and 7AAD; CD11chi 120G8neg DCs were sorted and restained with CD8-FITC and CD4-PE. Numbers in quadrants indicate the frequency of each DC subset. Results are representative of 5 such analyses. (D) Costimulatory molecule expression by freshly sorted or cultured (without anti-CD40 mAb) sort-purified CD11chi DCs from naive (fresh and cultured) or irradiated (irradiated) WT (gray fill) or RelB−/− (thick line) BMCs. Isotype control is shown as a fine line. (E) Cytokine levels in tissue culture supernatants from CD11chi DCs from WT or RelB−/− BMCs cultured with anti-CD40. The dotted line in each histogram represents the cytokine concentration in supernatants of RelB−/− BMC DCs cultured without anti-CD40 which were equivalent to levels from unstimulated WT BMC DCs. Results represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. (F) Sort-purified (H-2b) WT and RelB−/− BMC CD11chi DCs were used to stimulate naive (H-2d) CD4+ T cells in allogeneic MLCs. Proliferation and cytokine content of day 4 culture supernatants were measured as described in “Materials and methods.”

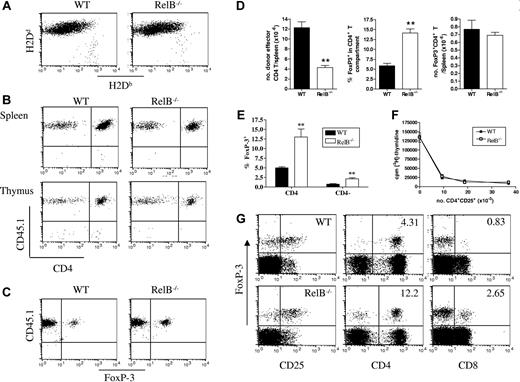

Abrogation of GVHD is associated with normal donor Treg expansion but impaired Th1 effector differentiation

To address the mechanism(s) by which the absence of RelB within host APCs attenuated GVHD, we first compared the degree of donor engraftment 10 days after BMT using flow cytometric analysis of splenic cell populations. As shown in Figure 3A, donor engraftment was equivalent and near complete (> 90%) in both the WT and RelB−/− BMC recipients of allogeneic grafts. Because the Balb/c→B6 model of GVHD depends on CD4+ T cells21 (and Figure S1A, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figures link at the top of the online article), we next examined the degree of donor CD4+ T-cell expansion after BMT. In initial experiments, we used splenic donor T cells from CD45.1+ congenic Balb/c mice and donor bone marrow from CD45.2+ Balb/c mice to differentiate T-cell expansion occurring in the periphery from that arising centrally via the thymus. As shown in Figure 3B, all CD4 T cells in the spleen (and LN; data not shown) of recipients were derived from the mature donor T-cell component of the graft 10 days after BMT. Interestingly, the vast majority of the small numbers of cells in the thymus (< 106) at this stage were also CD45.1+ (Figure 3B), reflecting the previously described recirculation of activated mature donor T cells.22 Finally, the FoxP3+ Treg cells in the periphery of BM transplant recipients were also all CD45.1+ and thus also derived from the mature donor T-cell inoculum within the graft (Figure 3C). Having demonstrated that all T cells in the BM transplant recipients were peripherally expanded from the mature donor T-cell inoculum at this time, we next quantified donor FoxP3− CD4+ effector (Teffector) and Treg expansion in the periphery of WT and RelB−/− BMC recipients. On day 10 after BMT the total number of splenic Teffector cells was significantly reduced in the RelB−/− BMC recipients as compared with the WT BMC recipients (Figure 3D). Strikingly, within the RelB−/− BMC recipients there was a 2- to 3-fold increase in the frequency of Treg cells as compared with WT BMC recipients. This resulted in equivalent overall expansion of Treg cells, despite the impairment of Teffector expansion (Figure 3D). Although the Treg expansion was predominantly in the CD25+ population, it was not limited to the classical CD4+Foxp3+ population but also included a CD8+Foxp3+ Treg population (Figure 3E,G). Importantly, the Treg cells that expanded in the RelB−/− BMC recipients had equivalent suppressive function to those in the WT BMC recipients (Figure 3F).

Abrogation of GVHD is associated with a decreased expansion of CD4+ effector T cells. Irradiated WT and RelB−/− BMCs were transplanted with BM from Balb/c (CD45.2+) donors in combination with T cells from congenic Balb/c (CD45.1+) donors, and spleens and thymi were harvested and dissociated 10 days after BMT. (A) Splenocytes were stained with mAb against H2Db and H2Dd to examine engraftment. (B) Splenocytes and thymocytes were stained with CD3, CD45.1. and CD4; CD3 T cells were gated and examined for CD4 and CD45.1 expression. Splenocytes were stained with CD3, CD45.1, CD4, and Foxp3, and (C) CD45.1 expression by FoxP3+ Treg cells was examined and (D) CD4+ T effector (CD3+CD4+FoxP3neg) and CD4+ Treg cells were enumerated **P < .01; WT (n = 6) versus RelB−/− BMCs (n = 6). (E) The percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ and CD4−FoxP3+ cells in WT and RelB−/− allograft recipients 10 days after BMT. **P < .01. Data represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. (F) Suppressive function (as described in “Materials and methods”) of day 10 ex vivo sort-purified CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from WT or RelB−/− BMCs recipients. (G) Four-color flow cytometry was used to phenotype and enumerate splenic FoxP3+ T cells (number in upper right quadrants represent percentage of CD4 or CD8 populations which were FoxP3+).

Abrogation of GVHD is associated with a decreased expansion of CD4+ effector T cells. Irradiated WT and RelB−/− BMCs were transplanted with BM from Balb/c (CD45.2+) donors in combination with T cells from congenic Balb/c (CD45.1+) donors, and spleens and thymi were harvested and dissociated 10 days after BMT. (A) Splenocytes were stained with mAb against H2Db and H2Dd to examine engraftment. (B) Splenocytes and thymocytes were stained with CD3, CD45.1. and CD4; CD3 T cells were gated and examined for CD4 and CD45.1 expression. Splenocytes were stained with CD3, CD45.1, CD4, and Foxp3, and (C) CD45.1 expression by FoxP3+ Treg cells was examined and (D) CD4+ T effector (CD3+CD4+FoxP3neg) and CD4+ Treg cells were enumerated **P < .01; WT (n = 6) versus RelB−/− BMCs (n = 6). (E) The percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ and CD4−FoxP3+ cells in WT and RelB−/− allograft recipients 10 days after BMT. **P < .01. Data represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. (F) Suppressive function (as described in “Materials and methods”) of day 10 ex vivo sort-purified CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from WT or RelB−/− BMCs recipients. (G) Four-color flow cytometry was used to phenotype and enumerate splenic FoxP3+ T cells (number in upper right quadrants represent percentage of CD4 or CD8 populations which were FoxP3+).

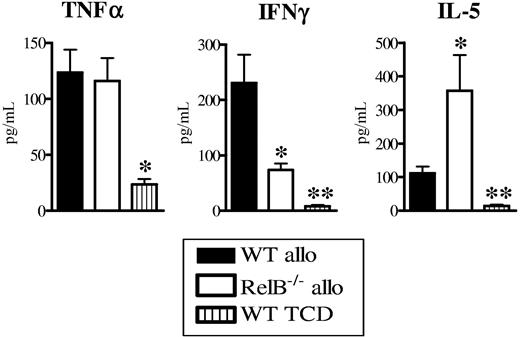

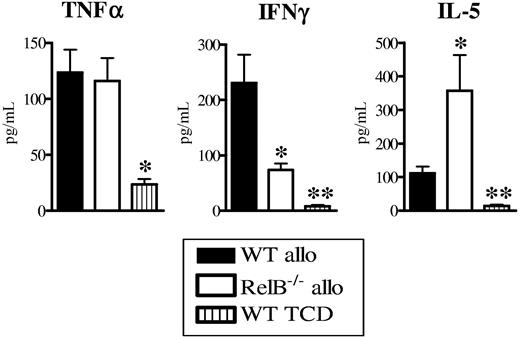

To study the relative states of T-cell differentiation after transplantation, we next examined the sera and CD4+ T-cell cytokine profiles in the WT and RelB−/− BMC allograft recipients. Whereas the levels of TNFα within sera were equivalent between groups, IFNγ was significantly reduced and IL-5 levels were increased in the RelB−/− BMC recipients compared with WT BMC recipients (Figure 4A). Donor CD4+ T cells purified from RelB−/− BMC allograft recipients produced significantly more of both IL-4 and IL-5 in response to alloantigen and CD3 relative to those from WT BMC recipients (Figure S2A-B). Although CD4 T cells from both recipients produced similar amounts of IFNγ in vitro, this is unlikely to fully recreate the stimuli in vivo, making the later the most relevant information. Thus, the absence of RelB−/− within host APCs resulted in equivalent Treg expansion to recipients where APCs had intact RelB but impaired Th1 effector expansion.

Abrogation of GVHD in RelB−/− BMCs is associated with donor Th2 differentiation. BMCs were transplanted as described in Figure 1B, and sera and spleen were collected 10 days after BMT. (A) TNFα, IFNγ, and IL-5 levels were determined in the sera as described in “Materials and methods.” Results represent mean ± SEM of individual animals. Data are from 1 of 3 representative experiments. WT allo (n = 5) versus RelB−/− allo (n = 5) or WT TCD (n = 3). *P < .05, **P = .01.

Abrogation of GVHD in RelB−/− BMCs is associated with donor Th2 differentiation. BMCs were transplanted as described in Figure 1B, and sera and spleen were collected 10 days after BMT. (A) TNFα, IFNγ, and IL-5 levels were determined in the sera as described in “Materials and methods.” Results represent mean ± SEM of individual animals. Data are from 1 of 3 representative experiments. WT allo (n = 5) versus RelB−/− allo (n = 5) or WT TCD (n = 3). *P < .05, **P = .01.

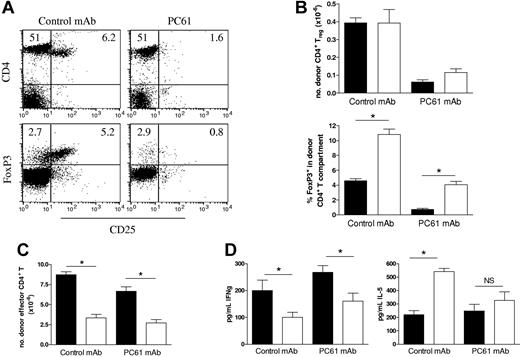

Impaired donor CD4 effector T-cell expansion in RelB−/− BMCs is independent of effects on Treg cells

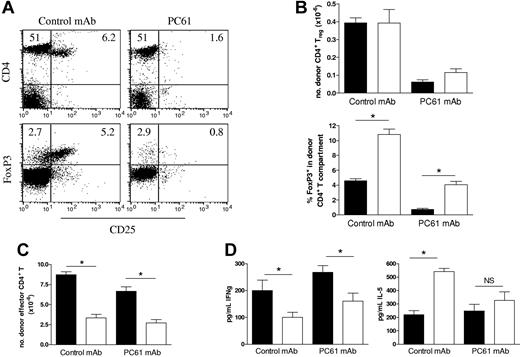

In addition to their effects on CD4 T-cell proliferation, both CD4+ and CD8+ Treg cells have been shown to suppress the capacity of mature DCs to induce Th1 responses23,24 and Th1-mediated pathologies, including GVHD.25–27 Thus, the defect in Th1 differentiation in the absence of RelB within host APCs may be the result of the increased proportions of Treg cells in these recipients. To examine this, we depleted CD25+ cells within donors by the administration of PC61 antibody which resulted in 75% depletion of CD4+CD25+ cells within LNs (Figure 5A). FoxP3 staining was used to confirm Treg depletion and demonstrated an 85% reduction in CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells and a sparing of a residual FoxP3+CD25− population (< 3%). These LN cell preparations were then used as the donor T-cell inoculum in subsequent transplants into WT and RelB−/− BMC recipients, and subsequent donor effector function was examined 10 days later. The depletion of donor Treg cells prior to BMT resulted in a greater than 80% reduction in the number of Treg cells recovered after BMT (Figure 5B). These residual Treg cells will therefore be derived from the FoxP3+CD25− cells transferred in the graft or generated de novo from FoxP3− naive cells. The absolute numbers of Treg cells were equivalent in RelB−/− and WT BMC recipients regardless of depletion of the CD25+ cells in the donor T-cell fraction, whereas the ratio of Treg to Teffector cells was again increased in RelB−/− BMC recipients. Importantly, depletion of Treg cells in WT or RelB−/− BMC recipients did not result in a significant increase in effector T-cell expansion (Figure 5C) or IFNγ generation (Figure 5D), and the failure of Th1 differentiation in RelB−/− BMC recipients persisted. Thus, the impairment of Th1 expansion is independent of the presence or function of donor Treg cells.

Treg cells expanded in RelB−/− BMCs are not responsible for the reduced effector T-cell expansion. Cohorts of irradiated WT and RelB−/− BMCs were transplanted with BM from PC61-treated Balb/c donors in combination with LN T cells from control or PC61-treated Balb/c donors. (A) Efficacy of donor Treg depletion was examined in LN cells from control mAb or PC61-treated Balb/c donors using 3-color flow cytometry with CD25-FITC, CD4-PE, and FoxpP3-Alexa647 mAbs (numbers represent proportion of LN cells in that quadrant). (B) Donor splenic CD4+ Treg (CD3+H2Dd-posCD4+FoxP3+) numbers and proportions within CD4+ compartment, and (C) effector CD4+ T cells (CD3+H2Dd-posCD4+FoxP3−) were quantitated, and (D) serum IFNγ and IL-5 levels were determined in allogeneic BMC transplant recipients 10 days after BMT. *P = .016, BMC transplant recipients: WT (■, n = 5) or RelB−/− (□, n = 4). Results represent mean ± SEM of individual animals.

Treg cells expanded in RelB−/− BMCs are not responsible for the reduced effector T-cell expansion. Cohorts of irradiated WT and RelB−/− BMCs were transplanted with BM from PC61-treated Balb/c donors in combination with LN T cells from control or PC61-treated Balb/c donors. (A) Efficacy of donor Treg depletion was examined in LN cells from control mAb or PC61-treated Balb/c donors using 3-color flow cytometry with CD25-FITC, CD4-PE, and FoxpP3-Alexa647 mAbs (numbers represent proportion of LN cells in that quadrant). (B) Donor splenic CD4+ Treg (CD3+H2Dd-posCD4+FoxP3+) numbers and proportions within CD4+ compartment, and (C) effector CD4+ T cells (CD3+H2Dd-posCD4+FoxP3−) were quantitated, and (D) serum IFNγ and IL-5 levels were determined in allogeneic BMC transplant recipients 10 days after BMT. *P = .016, BMC transplant recipients: WT (■, n = 5) or RelB−/− (□, n = 4). Results represent mean ± SEM of individual animals.

RelB within the donor graft is required for the maintenance of GVHD

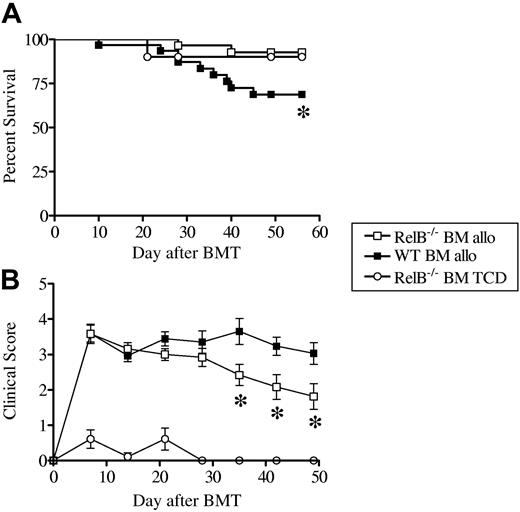

We next studied the role of donor RelB in a second established model of acute GVHD (B6→B6D2F1). As would be predicted given that the host APCs were RelB competent, GVHD was rapidly induced in recipient mice given transplants with either WT or RelB−/− bone marrow (BM) and RelB-competent T cells. The absence of RelB in the donor BM had no effect on clinical scores for the first 3 weeks after transplantation (Figure 6B). Although the GVHD clinical scores for recipients of WT bone marrow remained high after transplantation, subsequent to the initial 3-week period, clinical scores for recipients of RelB−/− BM decreased over time, and this was associated with a significant survival advantage (Figure 6A), confirming that RelB-competent donor APCs were required for the full spectrum of GVHD (Figure 6B). The presence of RelB−/− donor APCs did not impair the class I–dependent graft-versus-leukemia effect against host type P815 leukemia (Figure S2C), although further studies are needed to document the effect of RelB−/− host APCs on GVL.

RelB within the donor graft is required for the maintenance of GVHD. Cohorts of irradiated B6D2F1 mice were given transplants of WT (n = 31) or RelB−/− (n = 29) BM supplemented with or without purified RelB-competent T cells (TCD, n = 10). (A) Survival curves by Kaplan-Meier analysis, (B) GVHD clinical scores were determined weekly as described in “Materials and methods.” Data represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. Data were pooled from 4 similar experiments. *P < .03, WT versus RelB−/− allo recipients.

RelB within the donor graft is required for the maintenance of GVHD. Cohorts of irradiated B6D2F1 mice were given transplants of WT (n = 31) or RelB−/− (n = 29) BM supplemented with or without purified RelB-competent T cells (TCD, n = 10). (A) Survival curves by Kaplan-Meier analysis, (B) GVHD clinical scores were determined weekly as described in “Materials and methods.” Data represent mean ± SEM from individual animals. Data were pooled from 4 similar experiments. *P < .03, WT versus RelB−/− allo recipients.

Taken together, the attenuation of GVHD early after transplantation in RelB-deficient recipients and the failure to induce the full spectrum of GVHD in recipients of RelB−/− BM demonstrate that functional RelB is required for both the initiation and maintenance of GVHD.

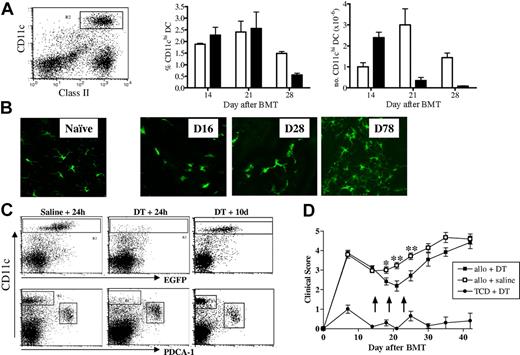

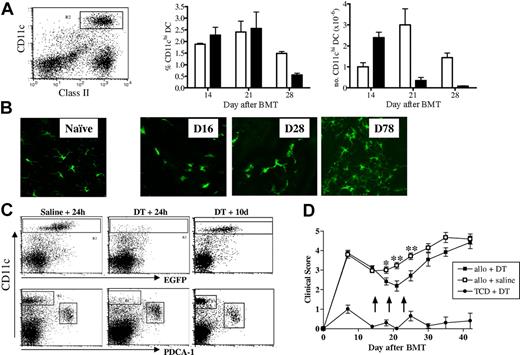

Donor cDCs reconstitute within 2 weeks of BMT

The delayed induction of GVHD in the RelB−/− BMC recipients and the reduction in GVHD seen in recipients of RelB−/− BM commenced approximately 3 weeks after transplantation. To examine whether this coincided with the emergence of donor DCs, we transplanted CD45.1+ TCD BM, alone or supplemented with T cells, into B6D2F1 recipients and enumerated splenic donor-derived CD11chi cDCs at weekly intervals after transplantation (Figure 7A). Minimal donor CD11chi cDC reconstitution was evident at day 7; however, by day 14 all cDCs were of donor origin (data not shown) and represented approximately 2% of splenocytes in both TCD and T-cell replete recipients. At later time points the proportion of cDCs remained similar in both groups; however, after 2 weeks the absolute number of cDCs in the T-cell–replete recipients declined because of the lymphoid hypoplasia associated with GVHD. To follow the turnover of skin DCs, BM from MacGreen mice, in which the Langerhans cells within the skin are exclusively EGFP+,28 was supplemented with WT T cells and transplanted into B6D2F1 recipients. EGFP+ Langerhans cells within the ear pinnae were visualized by confocal microscopy at weekly intervals after BMT (Figure 7B). The reconstitution of donor Langerhans cells within the skin began within a similar timeframe to that of splenic CD11chi cDCs but was not complete until 2 to 3 months after transplantation.

Donor DC reconstitution after BMT and their effect on GVHD. B6D2F1 mice received transplants of WT bone marrow with or without purified WT T cells, and splenocytes were harvested at weekly intervals. (A) DCs were enriched by density-gradient centrifugation and stained with class II-FITC, H2Dd-PE, CD11c-allophycocyanin, and H2Dd-neg CD11chi DCs were gated and enumerated. Results represent mean ± SEM, n = 3/group at each time point. Recipients of TCD BM (□) and BM + T (■) cells are represented. (B) B6D2F1 mice received transplants of c-fms/EGFP “MacGreen” bone marrow supplemented with or without purified WT T cells, and GFP+ Langerhans cells in ear pinnae were visualized by confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Watzlar, Germany) at times indicated. Naive refers to an untreated MacGreen mouse. (C) B6D2F1 recipients were given transplants of CD11c-DTR Tg TCD BM with or without WT T cells and treated with DT or saline (arrows) as described in “Materials and methods.” To examine depletion efficiency and subsequent DC reconstitution, 24 hours and 10 days after the final DT injections, spleens were harvested, density-gradient–enriched, and stained with PDCA-1–PE, 7AAD, and CD11c-allophycocyanin. Shown are TCD BM recipients. (D) GVHD clinical scores were determined weekly as described in “Materials and methods.” Arrows indicate time of DT or saline injections. Data represent mean ± SEM of individual animals. *P < .05, **P < .01; allo + DT versus allo + saline recipients (n = 11-15/group).

Donor DC reconstitution after BMT and their effect on GVHD. B6D2F1 mice received transplants of WT bone marrow with or without purified WT T cells, and splenocytes were harvested at weekly intervals. (A) DCs were enriched by density-gradient centrifugation and stained with class II-FITC, H2Dd-PE, CD11c-allophycocyanin, and H2Dd-neg CD11chi DCs were gated and enumerated. Results represent mean ± SEM, n = 3/group at each time point. Recipients of TCD BM (□) and BM + T (■) cells are represented. (B) B6D2F1 mice received transplants of c-fms/EGFP “MacGreen” bone marrow supplemented with or without purified WT T cells, and GFP+ Langerhans cells in ear pinnae were visualized by confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Watzlar, Germany) at times indicated. Naive refers to an untreated MacGreen mouse. (C) B6D2F1 recipients were given transplants of CD11c-DTR Tg TCD BM with or without WT T cells and treated with DT or saline (arrows) as described in “Materials and methods.” To examine depletion efficiency and subsequent DC reconstitution, 24 hours and 10 days after the final DT injections, spleens were harvested, density-gradient–enriched, and stained with PDCA-1–PE, 7AAD, and CD11c-allophycocyanin. Shown are TCD BM recipients. (D) GVHD clinical scores were determined weekly as described in “Materials and methods.” Arrows indicate time of DT or saline injections. Data represent mean ± SEM of individual animals. *P < .05, **P < .01; allo + DT versus allo + saline recipients (n = 11-15/group).

Depletion of donor CD11c+ DCs after BMT attenuates GVHD

To directly examine whether donor-derived CD11chi DCs contribute to GVHD, we used CD11c-DTR-GFP transgenic (Tg) mice as donors in which the diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor and EGFP are controlled by the CD11c promoter. Thus, DCs can be tracked using GFP expression and transiently depleted with diphtheria toxin.29 Transplant recipients were then depleted of DCs by the administration of DT during a 10-day period, commencing at the time of complete donor DC reconstitution (day 14). This was effective in depleting greater than 90% of repopulating CD11chi DCs while sparing the PDCA-1+ plasmacytoid DCs and resulted in a transient decrease in GVHD clinical scores (Figure 7C-D). DCs reconstituted within 10 days of the final injection of DT (day 28), at which time GVHD increased consistent with a causal role for these cells in maintaining GVHD.

Discussion

Our understanding of GVHD pathophysiology has greatly expanded over the past decade as we learn more about the complex interaction between APCs and T-cell subsets of both recipient and donor origin. The first demonstration of the importance of recipient APCs on GVHD in CD8-dependent GVHD8 has now been balanced by the confirmation that either recipient or donor APCs are sufficient to induce CD4-dependent GVHD.9,30 In this study, we demonstrate that the activation of RelB within DCs is a critical pathway determining the effective induction of GVHD, regardless of whether the DCs are of recipient or donor origin. In the absence of RelB activation, acute GVHD is attenuated by the limitation of full Th1 differentiation.

The realization that APCs are critical to the induction of effective GVL and the ability of specific APCs to induce tolerance via the induction of regulatory T cells that permit effective GVL12,32 has lead to the concept of functionally modifying rather than depleting APCs to separate GVHD and GVL. At the present time the relative contribution of particular APC subsets to the induction of GVHD is not clear, although much circumstantial evidence has previously suggested that DCs at least are critical in initiating the process.10,33 Although host B cells were reduced in the RelB−/− BMCs, they have been shown not to play a pathogenic role in this model of GVHD34 and thus are unlikely to be involved in the reduction in GVHD seen in these recipients. Similarly, although the RelB−/− BMCs have increased proportions of splenic FoxP3+ Treg cells (Figure S1B), this does not equate to increased total numbers, and these cells have previously been shown to be able to modulate GVHD only in MHC-matched35 but not in MHC-disparate models36 as studied here. Thus, the published data and that presented here suggest that professional APCs and, most likely, conventional CD11chi DCs control the induction of GVHD, and the translocation of RelB in these cells predate and predict the subsequent acquisition of their full immunologic potential. Because DCs mature in response to activation signals mediated by radiation, CD40L, or microbial products signaling through the TLRs, they express high levels of MHC and costimulatory molecules (particularly CD40, CD80, and CD86) and secrete cytokines important in Th1 differentiation. Importantly, the stimulation of DCs through ligation of CD40 or the lymphotoxin-β and BAFF receptors following lymphocyte engagement invoke these effects in a RelB-dependent fashion.7 Because the costimulatory molecule expression by host (Figure 2) and reconstituting RelB-deficient donor DCs were similar to that of WT DCs (Figure S1C), alternative defects are responsible for the failure of Th1 differentiation and maintenance of Treg expansion in this setting. Impaired secretion of relevant soluble mediators downstream of CD40 ligation such as IL-12, IL-23, or IL-27 that are known to be RelB dependent are the clear and most likely candidates.

A role for DCs in the development of peripheral tolerance through the induction of Treg cells has been supported by several studies. The induction of immunity or tolerance by DCs has been linked previously to their maturation state.37–39 Immature DCs generated from murine bone marrow induced T-cell unresponsiveness in vitro and prolonged cardiac allograft survival.39 Immature myeloid DCs induced CD4+ Treg cells in vitro and CD8+ Treg cells in vivo, each of which produced high levels of IL-10.37,38 Various agents shown to inhibit myeloid DC maturation have thus been described to promote Treg cells.40–44 We have also previously shown that bone marrow–derived DCs which are rendered incapable of translocating RelB to the nucleus are capable of inducing IL-10–producing Treg cells and inhibiting autoimmunity.25 In contrast, RelB-deficient APCs expand Treg cells in the periphery in an equivalent fashion to WT APCs, and this process, unlike Th1 effector function, is thus independent of RelB and in some circumstances is actually promoted by its absence.25 This is entirely consistent with the known ability of immature or semimature DCs to promote Treg differentiation and activation.45

The effect of broad NFkB inhibitors on GVHD has already been studied in preclinical models with some success.46–48 The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib was able to inhibit GVHD when administered early after BMT in association with apoptosis of alloreactive T cells,47 consistent with effects on a broad range of cells, including the donor T cell. However, the prolonged or delayed use after BMT amplified GVHD mortality because of amplification of inflammatory cytokine generation,48 suggesting a narrow therapeutic window. These studies confirm that the nonspecific nature of these NFkB inhibitors within a broad range of target cells result in tolerance via alloreactive donor T-cell deletion rather than the induction of active T-cell regulation or deviation as is the case when RelB is specifically inhibited within APCs.

Taken together, the data indicate that the nuclear translocation of RelB is a key signaling pathway for the induction of Th1 immunity. Thus, disruption of RelB activation within DCs represents an attractive target for inhibition of Th1-mediated tissue injury, concomitantly sparing Treg expansion and function. In clinical practice, this will require that RelB inhibitors are directed specifically to APCs and most likely, DCs. This is now feasible with targeted delivery technology using DC-specific antibodies to chaperone inhibitors to cell subsets.49 Such an approach would theoretically permit the inhibition of Th1-mediated pathology and the reestablishment of regulatory T-cell–dependent tolerance in disorders characterized by autoimmunity and alloimmunity.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

K.P.A.M. is a NHMRC R.D. Wright Fellow. G.R.H. is an NHMRC Practitioner Fellow.

Authorship

Contribution: K.P.A.M. designed and performed research, analyzed the data, and contributed to manuscript preparation; R.D.K., V.R., T.B., H.B., B.O., K.A.M., and A.L.D. performed research; E.S.M. provided intellectual input and experimental design; R.T. provided intellectual input and experimental design; G.R.H. provided intellectual input and experimental design, and contributed to manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Geoff Hill, Bone Marrow Transplantation Laboratory, Queensland Institute of Medical Research, 300 Herston Rd, Herston, QLD 4006, Australia; e-mail: geoff.hill@qimr.edu.au.