Abstract

Thrombocytopenia has been consistently reported following the administration of adenoviral gene transfer vectors. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon is currently unknown. In this study, we have assessed the influence of von Willebrand Factor (VWF) and P-selectin on the clearance of platelets following adenovirus administration. In mice, thrombocytopenia occurs between 5 and 24 hours after adenovirus delivery. The virus activates platelets and induces platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation. There is an associated increase in platelet and leukocyte-derived microparticles. Adenovirus-induced endothelial cell activation was shown by VCAM-1 expression on virus-treated, cultured endothelial cells and by the release of ultra-large molecular weight multimers of VWF within 1 to 2 hours of virus administration with an accompanying elevation of endothelial microparticles. In contrast, VWF knockout (KO) mice did not show significant thrombocytopenia after adenovirus administration. We have also shown that adenovirus interferes with adhesion of platelets to a fibronectin-coated surface and flow cytometry revealed the presence of the Coxsackie adenovirus receptor on the platelet surface. We conclude that VWF and P-selectin are critically involved in a complex platelet-leukocyte-endothelial interplay, resulting in platelet activation and accelerated platelet clearance following adenovirus administration.

Introduction

Acute thrombocytopenia has been consistently reported following intravenous administration of adenovirus.1-3 Thrombocytopenia is transient and vector dose-dependent but the mechanism underlying this adverse event currently remains unclear.

P-selectin is a member of the selectin family of cell adhesion molecules that mediate binding to specific carbohydrate-containing ligands. The protein is localized in the α granules of platelets and the Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells.4,5 The most clearly identified ligand for P-selectin is PSGL-1, which is detected on the majority of leukocytes and also present in small amounts on platelets.6,7 P-selectin supports initial tethering of leukocytes to activated endothelial cells and to activated platelets and mediates leukocyte rolling on the endothelial cell surface.8 A soluble form of P-selectin resulting from proteolytic shedding of the extracellular domain has been detected in human9 and mouse10 plasma and was found to maintain the requirements for ligand binding.11 Elevated levels of plasma P-selectin are seen in a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and thrombotic disorders.12,13

A critical step in the response to vascular injury is the interaction between platelets and the adhesive protein von Willebrand factor (VWF), which mediates platelet translocation and adhesion to the exposed subendothelium.14 VWF binding to platelets is mediated through platelet GPIb and this interaction acts as a complementary binding event to the tethering of leukocytes to platelets through a Mac1–P-selectin interaction.15 Furthermore, activation of the endothelium is associated with the rapid release of Weibel-Palade bodies whose principal constituent, besides P-selectin, is ultra-large multimers of VWF.16

Activated endothelium is also associated with the up-regulation of VCAM-1 and other adhesion molecules that mediate slowing of leukocytes, firm tethering, and eventually transendothelial leukocyte migration.17

Activated platelets in the circulation associate rapidly with leukocytes forming aggregates that roll on the endothelium. Activated platelets themselves support leukocyte recruitment and rolling onto endothelial cell-bound ultra-large VWF (ULVWF) molecules.18 While the initial platelet-leukocyte tethering is mediated via P-selectin/PSGL-1, subsequent firm adhesion involves the leukocyte integrin αMβ2 (Mac-1), which binds either GPIb19 or fibrinogen bound to the αIIbβ3 or αvβ3 integrin.20,21 Activated platelets are known to be engulfed by scavenger macrophages and are cleared by the reticuloendothelial system in the spleen and liver.22

Adenovirus-induced thrombocytopenia is a potentially serious complication of gene therapy protocols using this type of vector. Understanding its mechanism may help the development of measures to prevent this adverse event. In this report, we have studied platelet-adenovirus interactions in vitro and in vivo after intravenous administration of adenovirus to mice. We show that adenovirus induces platelet activation and promotes the formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates both in vitro and in vivo. Cellular microparticle release is also induced. We demonstrate, for the first time, the presence of the Coxsackie adenovirus receptor (CAR) on the platelet surface and provide evidence of adenovirus platelet attachment. We also report a role for the virus in stimulating endothelial cells and ULVWF release and show that both P-selectin and VWF are key elements in mediating accelerated clearance of platelets by the reticuloendothelial system.

Materials and methods

Animals and animal procedures

Male and female Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice between 8 and 12 weeks old were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) The VWF−/−C57BL/6 mice were obtained by breeding C57BL/6 VWF−/+ mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Blood sampling was performed via the retro-orbital plexus or saphenous vein. Cardiac puncture was considered when mice were humanely killed and when 1 mL blood was needed for testing. Animal studies were performed in accordance with the regulations of the Canadian Council for Animal Care and with approval of the Queen's University Animal Care Committee.

Adenoviral vector

These studies used an early generation, E1/E3 deleted, replication-deficient adenovirus derived from human adenovirus group C, serotype 5. The vector was propagated in 293 cells and purified on CsCl density gradient centrifugation as previously described.23,24 Vectors were dialyzed against Tris buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 3% sucrose, 2% glycerol) and the vector titer was determined by spectrophotometric measurement of the optical density at 260 nm and reported as virus particles per milliliter (vp/mL). All mice received 1 × 1011 vp through a single tail vein injection. Control mice for platelet count and platelet activation experiments received 0.4 ng LPS (Sigma, Oakville, ON, Canada) by tail vein injection.

Blood collection, preparation of platelets, and blood counts

Murine blood was collected in acid citrate dextrose (ACD) anticoagulant 1:6 for experiments using washed platelets and in a 1:9 trisodium citrate anticoagulant for platelet adhesion studies using platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and for plasma VWF assays. PRP was prepared by centrifugation at 150g for 8 minutes at room temperature (RT). Platelets were pelleted by centrifugation at 1200g for 5 minutes. The resulting pellet was washed in buffer A (140 mM NaCl,5 mM KCl,12 mM trisodium citrate,10 mM glucose,12.5 mM sucrose, pH, 6) and resuspended in buffer B (140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). To induce activation, platelets were treated with human thrombin (Sigma) 0.2 U/mL for 2 minutes. Human platelets used in this study were obtained from platelet concentrates at day 5 of storage. Murine platelet count was assessed on an automated analyser (Vet ABC, cdmv, Montreal, QC, Canada) and results were reported as count × 103/mL.

Platelet P-selectin expression

P-selectin appears rapidly on the surface of activated platelets. Murine pooled platelets incubated with adenovirus in vitro for 30 minutes at 37°C or those obtained from mice following intravenous adenovirus injection, were stained using purified rat anti–mouse P-selectin (CD 62P) antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and FITC-conjugated goat anti–rat IgG (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) and analyzed with flow cytometry. Control experiments were performed with resting and thrombin-activated platelets and with a rat isotype control antibody. The results were assessed by the percentage of positive cells as well as the index of platelet activation (IPA+; percentage of positive cells × mean channel fluorescence [MCF]).25

Assessment of platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation

Platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation was assessed as described by Tibbles and coworkers with modifications.26 Murine whole blood (after sedimentation of red cells) was incubated in vitro with adenovirus for 30 minutes at 37°C and blood samples obtained from mice following adenovirus injection, in vivo, were stained simultaneously with rat anti–mouse PE-CD45 and rat anti–mouse FITC-CD41 monoclonal antibodies (BD PharMingen, Mississuga, ON, Canada) for 30 minutes at RT. The double-positive events were analyzed by flow cytometry. Following gating of platelets based on CD41, the percentage of leukocytes (CD45+ events) associated with platelets was determined.

VWF studies

Plasma VWF was quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Microtiter plates were coated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti–human VWF antibody that cross-reacts with mouse VWF (no. A0092; Dako, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Plasma samples (diluted 1:30 in PBS) were incubated for 2 hours in the coated wells at RT then washed 6 times after which a rabbit anti–human VWFr HRP conjugate (no. P0226; Dako) 1:8000 was added for 2 hours. After washing, a color reagent was added to the wells and the colorimetric reaction was stopped with H2SO4 after 25 minutes. Results were read in an ELISA microplate reader at A490 nm against a standard curve based on pooled plasma obtained from 10 normal adult C57BL/6 mice. VWF multimers were analyzed by electrophoresis using a 1.4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) agarose gel followed by electrotransfer to a nylon membrane. The multimers were visualized using a chemiluminescent visualization kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Baie D'Urfe, QC, Canada).

Endothelial cell studies

Human blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOECs) were isolated from 50 mL blood from volunteers as previously described.27 Cells were maintained in MCBD131 media (Gibco BRL, Burlington, ON, Canada) supplemented with EGM-2 Clonetics TM (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD). Cells were grown in 60 mm plates and treated at 80% confluence with 3 adenovirus doses (1 × 108, 1 × 109, and 1 × 1 010 vp) for 6 hours. The percentage of VCAM-1 expression on the isolated and washed cells was determined by flow cytometry using PE-mouse anti–human CD106 (BD Biosciences, San Deigo, CA) and was compared to untreated cells. Culture media was also collected at 24 hours after adenovirus treatment for VWF quantitation.

Assessment of platelet, leukocyte, and endothelial microparticles

Microparticles (MPs) are vesiculations of plasma membranes that are released from cells during activation, stress, and apoptosis and are known to reflect the status of the original cell.28 In the literature, there is substantial debate as to the choice of the specific marker and techniques used for MP assessment (reviewed by Horstman et al29 ). In this study, we have chosen both CD41 (αIIb; GPIIB) and CD61 (β3; GPIIIa) for platelet MP detection and CD45 and CD62E for leukocyte and endothelial cell MP evaluation, respectively. MPs were assessed using flow cytometry as previously described.30 Briefly, 50 μL platelet-poor plasma (PPP) prepared from murine whole blood was incubated with the corresponding monoclonal antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. To compare particle size and also to calculate the absolute number of MPs, we used fluorescent beads of a standard size and concentration (no. 580; Cederlane, Hornby, ON, Canada) that were analyzed simultaneously with the MP sample of interest. The positively labeled particles and beads were then further separated on another histogram based on forward scatter versus fluorescence and MPs were defined as particles positive for specific antigens and of less fluorescent signal than control beads. The numbers of MPs were calculated using a ratio of the known number of beads used in each flow cytometry study.

Static platelet adhesion assay

We used a static platelet adhesion assay as described by Elbatarny and Maurice.31 Briefly, platelets were labeled with [3H] adenine. Platelets (1 × 108/mL) were then incubated under the following conditions: with and without adenovirus (1 × 108 vp/mL) and with ADP for 30 minutes at RT in individual wells of microtiter plates coated with fibronectin (10 μg/mL). Unbound platelets were removed by 3 washes with PBS (pH 7.4), bound platelets were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes, and 3H from the lysed cells was counted in a scintillation counter. Platelet adhesion, measured as 3H present in each platelet lysate sample, was expressed as a percentage of the total 3H that had been added to each well.

Detection of the CAR on human platelets

Washed human platelets were stained with purified mouse anti–human CAR (clone RmcB no. 05-644, Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Lake Placid, NY) for 2 hours at RT. After washing with PBS, rabbit anti–mouse FITC IgG (BD PharMingen) was added for 30 minutes and the percentage of CAR+ events was analyzed by flow cytometry. CAR-expressing HEK 293 cells and mouse isotype-matched antibody and unstained cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Platelet CAR expression was also evaluated by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis. RNA was extracted from human platelets by TRIzol TM (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A reverse transcriptase reaction was performed using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen) and the cDNA was used as a template for PCR amplification of the human CAR gene (accession no. Y07593) using primers as previously described.32 The resulting 366-bp PCR fragment was amplified by 40 cycles of PCR (denaturation, 15 seconds at 95°C; extension, 1 minute at 60°C).

Statistics

All values are presented as the mean plus or minus SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using the Student t test. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

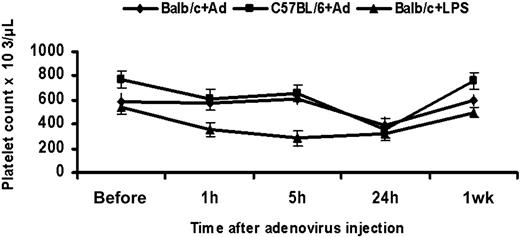

Thrombocytopenia occurs between 5 and 24 hours following intravenous administration of adenovirus to mice

We examined the platelet count in mice following tail vein injection of 1 × 1011 adenoviral particles. Consistent with previous reports,2,33 platelet counts were significantly reduced at 24 hours following virus administration when compared to the preinjection level in Balb/c (n = 8, P < .001) and C57BL/6 mice (n = 6, P < .001). The reduction of platelet count was 32% in Balb/c and 54% in C57BL/6 mice. There was also significant interindividual variation in platelet counts both at baseline and after adenoviral injection. The reduction in platelet count occurred between 5 and 24 hours following injection, and counts returned to normal within a week. Because thrombocytopenia is a known event following LPS treatment,34 we injected mice with 0.4 ng LPS as a positive control. Thrombocytopenia appeared as early as 1 hour following LPS injection (n = 3, P = .04) and counts remained significantly low at 5 hours and 24 hours (n = 3, P = .02; Figure 1). We have not assessed the platelet count between 5 and 24 hours or between 24 hours and 1 week due to a limitation on blood sampling in our mice. However, Wolins and coworkers have shown that the nadir of the platelet count after intravenous injection of a comparable dose of adenovirus in rhesus monkeys was 48 hours.33

Thrombocytopenia in adenovirus and LPS-treated mice. Platelet counts were assessed following tail vein injection of 1 × 1011 adenoviral particles into each of Balb/C and C57/ BL6 mice. The platelet count falls significantly at 24 hours (Balb/c: n = 8, P < .001; C57BL/6: n = 6, P = .002) and returns to normal at 1 week. In Balb/c mice receiving 0.4 ng LPS, the platelet count falls significantly as early as 1 hour (n = 3, P = .04) and remains low at 5 and 24 hours (n = 3, P = .02). Values are the mean ± SEM.

Thrombocytopenia in adenovirus and LPS-treated mice. Platelet counts were assessed following tail vein injection of 1 × 1011 adenoviral particles into each of Balb/C and C57/ BL6 mice. The platelet count falls significantly at 24 hours (Balb/c: n = 8, P < .001; C57BL/6: n = 6, P = .002) and returns to normal at 1 week. In Balb/c mice receiving 0.4 ng LPS, the platelet count falls significantly as early as 1 hour (n = 3, P = .04) and remains low at 5 and 24 hours (n = 3, P = .02). Values are the mean ± SEM.

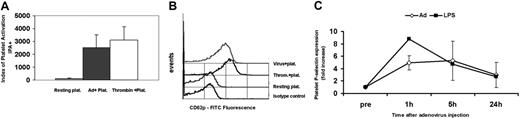

Adenovirus activates platelets and induces rapid exposure of P-selectin

P-selectin expression was assessed before injection and at 1 hour, 5 hours, and 24 hours following virus administration. We have used the index for platelet activation (IPA+; MCF × percentage of positive events) in our initial experiments to reflect the true levels of CD62p expression in the entire platelet population.25 Our in vitro data showed a significant increase in the IPA+ for platelets incubated with virus compared to resting platelets (IPA+ 128.2 resting; 2519.4 adenovirus; 3095.3 thrombin activated; Figure 2A-B). Our in vivo data also showed a significant 5-fold increase in the percentage of CD62p+ platelets at 1 hour following virus injection (7.2% to 37.3%) compared to preinjection levels (n = 4, P < .001; Figure 2C). In LPS-treated mice, the increase in CD62p+ platelets at 1 hour was 8.8-fold (8.3% to 72.9%). These results collectively indicate that platelets are activated when they come in contact with adenovirus in vitro and in vivo.

Expression of platelet P-selectin (CD62p) in vitro and following intravenous administration of adenovirus to mice. (A) Murine washed platelets were incubated with adenovirus for 30 minutes at 37°C and analyzed for CD62p by flow cytometry. The index of platelet activation IPA+ (MCF × percentage of CD62+ events) is significantly increased in adenovirus (Ad)–treated platelets compared to resting platelets (average of 5 experiment). Thrombin-activated platelets are tested as a positive control. (B) Flow cytometry histogram representative of 5 in vitro experiments showing increased fluorescence in adenovirus-treated platelets and thrombin-activated platelets compared to resting platelets and the isotype control. (C) Platelet P-selectin expression during the first 24 hours following adenovirus or LPS intravenous administration in mice. Graph represents fold increase of percent of P-selectin positive platelets after adenovirus compared to preinjection levels. Significant P-selectin expression is significant in both LPS and adenovirus treated at 1 hour compared to the preinjection level (adenovirus-treated mice n = 4, P < .001). Values are the mean ± SEM.

Expression of platelet P-selectin (CD62p) in vitro and following intravenous administration of adenovirus to mice. (A) Murine washed platelets were incubated with adenovirus for 30 minutes at 37°C and analyzed for CD62p by flow cytometry. The index of platelet activation IPA+ (MCF × percentage of CD62+ events) is significantly increased in adenovirus (Ad)–treated platelets compared to resting platelets (average of 5 experiment). Thrombin-activated platelets are tested as a positive control. (B) Flow cytometry histogram representative of 5 in vitro experiments showing increased fluorescence in adenovirus-treated platelets and thrombin-activated platelets compared to resting platelets and the isotype control. (C) Platelet P-selectin expression during the first 24 hours following adenovirus or LPS intravenous administration in mice. Graph represents fold increase of percent of P-selectin positive platelets after adenovirus compared to preinjection levels. Significant P-selectin expression is significant in both LPS and adenovirus treated at 1 hour compared to the preinjection level (adenovirus-treated mice n = 4, P < .001). Values are the mean ± SEM.

Adenovirus induces platelet-leukocyte aggregates and promotes the release of platelet and leukocyte MPs

Activated platelets in the circulation associate rapidly with leukocytes to form aggregates35 that are considered as biomarkers for tissue injury during inflammation. We examined platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation following incubation of whole blood in vitro with the virus and at 1 hour, 5 hours, and 24 hours following intravenous injection of adenovirus in mice. The percentage of leukocytes associated with platelets (CD41/45 double-positive events) was significantly higher at 1 hour (1.4-fold increase) and 24 hours (1.8-fold increase) following virus injection when compared to the preinjection level (n = 4, P = .01 and .001, respectively; Figure 3A). We then evaluated postinjection samples for the release of platelet and leukocyte microparticles (PMPs, LMPs, respectively) as documented in other inflammatory conditions. We demonstrated a significant increase in the number of PMPs as shown by CD41 (αIIB integrin/GPIIb subunit) and CD61 (GPIIIa/β3 integrin subunit), each assessed separately, at 2 hours following virus administration. The numbers of CD41+ MPs/μL in plasma were 55 and 455.7, and for CD61+ MPs 108.7 and 717.4, as measured before and 2 hours after virus injection, respectively (n = 3, P = .02; P < .001). Similarly, based on the CD45 marker, the number of LMPs/μL plasma was 1904.1 at 2 hours versus 260.3 before injection (n = 3, P = .03), documenting the activation of leukocytes (Figure 3B).

Adenovirus induces platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation and both platelet and leukocyte MPs following intravenous administration to mice. (A) Whole blood samples obtained from Balb/c mice during the first 24 hours following injection of adenovirus. Flow cytometry assessment of platelet-leukocyte aggregate was performed as follows: platelets were first gated based on the CD41 marker and the percentage of CD45+ cells (leukocytes) associated with platelets was assessed on another histogram. The upper right quadrants of the histograms show an evolving significant increase in platelet-leukocyte aggregates from before to various time points following adenovirus treatment. These data are representative of 3 independent in vivo experiments. (B) Graphs showing the average number of MPs in plasma obtained from Balb/c mice based on separate assessment of CD41 and CD61 (PMPs) and CD45 (LMPs). There is a significant increase in PMPs (n = 3, P = .02 based on CD41; P < .001 based on CD61 marker) and LMPs (n = 3, P = .03) at 2 hours following virus administration compared to the preinjection levels (Before). Values shown are the mean ± SEM.

Adenovirus induces platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation and both platelet and leukocyte MPs following intravenous administration to mice. (A) Whole blood samples obtained from Balb/c mice during the first 24 hours following injection of adenovirus. Flow cytometry assessment of platelet-leukocyte aggregate was performed as follows: platelets were first gated based on the CD41 marker and the percentage of CD45+ cells (leukocytes) associated with platelets was assessed on another histogram. The upper right quadrants of the histograms show an evolving significant increase in platelet-leukocyte aggregates from before to various time points following adenovirus treatment. These data are representative of 3 independent in vivo experiments. (B) Graphs showing the average number of MPs in plasma obtained from Balb/c mice based on separate assessment of CD41 and CD61 (PMPs) and CD45 (LMPs). There is a significant increase in PMPs (n = 3, P = .02 based on CD41; P < .001 based on CD61 marker) and LMPs (n = 3, P = .03) at 2 hours following virus administration compared to the preinjection levels (Before). Values shown are the mean ± SEM.

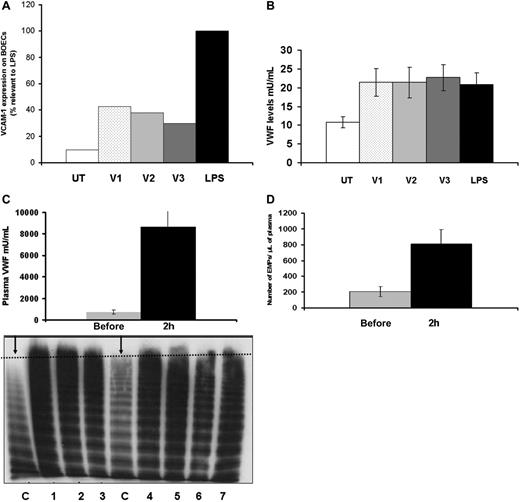

Adenovirus activates endothelial cells, induces rapid release of ULVWF, and causes endothelial MP release

To investigate the role of VWF in adenovirus-induced platelet clearance, we first examined the effect of adenovirus on human BOECs. In vitro, adenovirus-treated BOECs showed a significant increase in VCAM-1 expression after 6 hours of virus incubation. Whereas LPS treatment resulted in a 10.2-fold increase of VCAM-1 expression, adenovirus treatment resulted in 4.37-, 3.87-, and 3-fold increases with the 3 viral doses (V1, V2, and V3) respectively (Figure 4A). In addition, the amount of VWF assayed in culture media 24 hours following virus treatment was significantly higher when compared to untreated cells (n = 3, P = .03, .04, and .02 for V1, V2, and V3, respectively) reflecting non–dose-dependent endothelial cell activation (Figure 4B). LPS exposure of endothelial cells resulted in similar levels of VWF release (n = 3, P = .02). We then studied the effect of adenovirus on endothelial cells and VWF release in vivo. We measured plasma VWF levels in Balb/c mice 2 hours after injection of adenovirus. The average plasma VWF was 721.66 versus 8631.86 mU/mL for samples before and 2 hours after virus injection, respectively (n = 7, P = .003), representing a 11.9-fold increase in the VWF level. In addition to an increase in the absolute amount of plasma VWF, we also demonstrated ultra-large molecular weight VWF multimers in plasma obtained from 7 mice 1 to 2 hours following injection of adenovirus (Figure 4C). This confirms that the VWF originated from stimulated endothelial cells with subsequent exocytosis of Weibel-Palade (WB) bodies. The acute elevation of plasma VWF was also associated with a significant increase in endothelial MPs (EMPs), based on an assessment of E-selectin (CD 62E)–expressing MPs. The numbers of EMPs were 209.6 versus 807.68 MPs/μL for samples before and after injection, respectively (n = 3, P = .03; Figure 4D). These results collectively indicate that adenovirus activates endothelial cells, stimulates the generation of endothelial cell-derived MPs, and induces release of ULVWF multimers that may play a role in mediating thrombocytopenia following adenovirus injection.

Adenovirus activates endothelial cells in vitro and induces release of ultra-large molecular weight VWF as well as EMPs following intravenous administration in mice. (A) BOECs were treated with 3 doses of adenovirus (V1-3) for 6 hours. Cells were then harvested, washed, and stained with fluorescent-labeled anti–human VCAM-1 and assessed by flow cytometry. BOECs treated with LPS were used as a positive control and LPS data were set at 100% (average of 3 experiments). (B) BOEC culture media was collected at 24 hours following adenovirus treatment for VWF quantitation. There was a non–dose-dependent increase in VWF levels when compared to the untreated cells. (C) Plasma samples from Balb/C mice were collected 1 to 2 hours following intravenous administration of adenovirus. VWF levels increased significantly (11.9-fold above preinjection level; upper panel) and ultra-large molecular weight VWF multimers appear on multimer analysis of murine Balb/c plasma (lower panel). The figure shows an increased multimer density (increased VWF) as well as ultra-large multimers in the 7 adenovirus-treated mice (lanes1-7) compared to control mouse plasma (C lanes, represented by the two arrows). The dotted line shows highest molecular weight multimer in normal mice. (D) The number of EMPs in plasma obtained from Balb/c mice after intravenous virus administration based on CD62E expression increases significantly following administration (n = 3, P = .03). Values shown are the mean ± SEM.

Adenovirus activates endothelial cells in vitro and induces release of ultra-large molecular weight VWF as well as EMPs following intravenous administration in mice. (A) BOECs were treated with 3 doses of adenovirus (V1-3) for 6 hours. Cells were then harvested, washed, and stained with fluorescent-labeled anti–human VCAM-1 and assessed by flow cytometry. BOECs treated with LPS were used as a positive control and LPS data were set at 100% (average of 3 experiments). (B) BOEC culture media was collected at 24 hours following adenovirus treatment for VWF quantitation. There was a non–dose-dependent increase in VWF levels when compared to the untreated cells. (C) Plasma samples from Balb/C mice were collected 1 to 2 hours following intravenous administration of adenovirus. VWF levels increased significantly (11.9-fold above preinjection level; upper panel) and ultra-large molecular weight VWF multimers appear on multimer analysis of murine Balb/c plasma (lower panel). The figure shows an increased multimer density (increased VWF) as well as ultra-large multimers in the 7 adenovirus-treated mice (lanes1-7) compared to control mouse plasma (C lanes, represented by the two arrows). The dotted line shows highest molecular weight multimer in normal mice. (D) The number of EMPs in plasma obtained from Balb/c mice after intravenous virus administration based on CD62E expression increases significantly following administration (n = 3, P = .03). Values shown are the mean ± SEM.

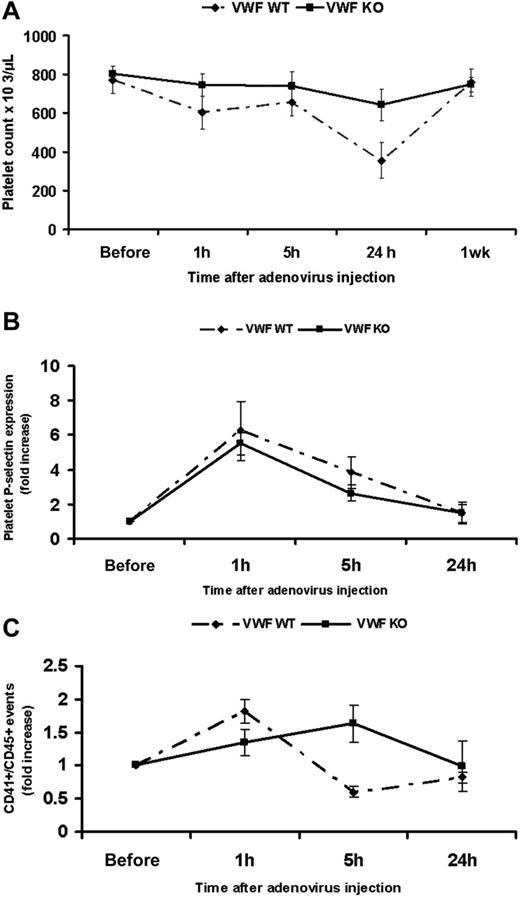

VWF−/− mice do not show significant thrombocytopenia following adenovirus administration

To further evaluate the role of VWF in mediating adenovirus-induced thrombocytopenia, we examined the effect of the virus on the platelet count, platelet activation, and platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation following administration to VWF−/− C57BL/6 mice. Our data showed that, in contrast to the VWF+/+ mice, the VWF−/− mice did not show significant thrombocytopenia at 24 hours after adenovirus administration (n = 6, P = .002 in VWF+/+ versus n = 6, P = .06 in VWF−/−; Figure 5A). The reduction in platelet count was only 19% in VWF−/− mice compared to 54% in VWF+/+ mice. Levels of platelet P-selectin at 1 hour following virus injection showed a significant 5.5-fold increase in VWF−/− mice and 6.25-fold increase in VWF+/+ mice (n = 3, P < .001 in both VWF−/− and VWF+/+; Figure 5B). Comparing levels at 1 hour, platelets from VWF−/− showed significantly less P-selectin expression when compared to VWF+/+ mice (n = 3, P = .01). Furthermore, unlike the VWF+/+ mice, the VWF−/− animals did not show significant platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation at 1 hour after virus administration (VWF−/− n = 3, P = .12 versus VWF+/+ n = 3, P = .007). The percentage of CD41/CD45 double-positive events showed a 1.3-fold increase in VWF−/− mice and a 1.8-fold increase in VWF+/+ (Figure 5C), suggesting an important role for VWF in mediating the interaction of platelets with leukocytes. In aggregate, these results show that VWF is a major, but not the sole, player in mediating thrombocytopenia following adenovirus injection in mice. P-selectin is also likely contributing to this process.

VWF KO mice do not show significant thrombocytopenia, experience a level of P-selectin expression but do not form platelet leukocyte aggregates following adenovirus administration. (A) Platelet counts were assessed at 1 hour, 5 hours, 24 hours, and 1 week following intravenous administration in WT and VWF−/−C57BL/6 mice showing nonsignificant thrombocytopenia in VWF−/− following adenovirus (n = 6, P = .002 in WT versus P = .06 in VWF KO mice). (B) Similar to VWF+/+ mice, platelets from VWF−/− mice show significant P-selectin expression at 1 hour after adenovirus injection (n = 3, P < .001) compared to preinjection expression but significantly lower when compared to WT (P = .01). (C) Graph showing nonsignificant platelet leukocyte aggregates at 1 hour following virus administration to VWF KO mice compared to the preinjection level (n = 3, P = .12 in KO versus P = .007 in WT mice)

VWF KO mice do not show significant thrombocytopenia, experience a level of P-selectin expression but do not form platelet leukocyte aggregates following adenovirus administration. (A) Platelet counts were assessed at 1 hour, 5 hours, 24 hours, and 1 week following intravenous administration in WT and VWF−/−C57BL/6 mice showing nonsignificant thrombocytopenia in VWF−/− following adenovirus (n = 6, P = .002 in WT versus P = .06 in VWF KO mice). (B) Similar to VWF+/+ mice, platelets from VWF−/− mice show significant P-selectin expression at 1 hour after adenovirus injection (n = 3, P < .001) compared to preinjection expression but significantly lower when compared to WT (P = .01). (C) Graph showing nonsignificant platelet leukocyte aggregates at 1 hour following virus administration to VWF KO mice compared to the preinjection level (n = 3, P = .12 in KO versus P = .007 in WT mice)

Variation in the strain of mouse had no effect on platelet activation or the formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates in Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice. However, adenovirus injection in C57BL/6 mice resulted in a 14-fold increase in VWF levels following virus administration (data not shown) compared to a 11.9-fold increase in Balb/c mice, which may, in part, explain the more severe thrombocytopenia seen in C57BL/6 mice.

Adenovirus interferes with platelet adhesion to fibronectin

We performed static platelet adhesion assays where radiolabeled platelets were incubated with adenovirus in fibronectin-coated wells. Our data showed that platelets adhered less to fibronectin-coated wells in the presence of virus (n = 4, P = .04) and that the virus interfered significantly with ADP-mediated potentiation of platelet adherence (n = 4, P = .008; Figure 6A). These results suggest that viral interference with platelet adhesion may be the result of virus binding to one of the platelet fibronectin receptors. The platelet adherence to adenovirus tested in our system is obviously not evaluating platelet adhesion responses to virus in a physiologic system. Furthermore, we have not assessed virus-induced platelet aggregation, but previous studies have shown that adenovirus does not affect aggregation in response to several different agonists.36

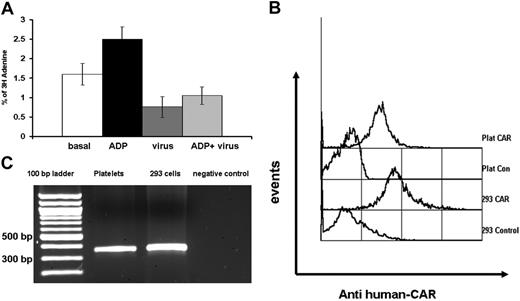

Platelets bind adenovirus and express CAR on their surface. The 3H-labeled platelets were allowed to adhere on fibronectin-coated wells with or without the virus and the extent of adhesion was determined after lysis and measurement of radioactivity. (A) Graph showing reduced platelet adhesion in the presence of the virus compared to basal platelet adhesion (n = 4, P = .04) and significant interference with ADP potentiation of platelet adhesion (n = 4, P = .008). Error bars represent ± SEM. (B) Platelets and CAR-expressing HEK 293 cells were stained with mouse monoclonal anti–human CAR antibody and FITC rabbit anti–mouse IgG and analyzed with flow cytometry. The flow cytometry histogram shows that platelets are positive for CAR (graph representative of 4 experiments). (C) The presence of CAR on platelets was verified by human platelet mRNA analysis; 1.5% agarose gel showing RT-PCR of platelet-derived RNA amplifying 366-bp band from the CAR gene. Lane 1 is a 100-bp molecular weight ladder.

Platelets bind adenovirus and express CAR on their surface. The 3H-labeled platelets were allowed to adhere on fibronectin-coated wells with or without the virus and the extent of adhesion was determined after lysis and measurement of radioactivity. (A) Graph showing reduced platelet adhesion in the presence of the virus compared to basal platelet adhesion (n = 4, P = .04) and significant interference with ADP potentiation of platelet adhesion (n = 4, P = .008). Error bars represent ± SEM. (B) Platelets and CAR-expressing HEK 293 cells were stained with mouse monoclonal anti–human CAR antibody and FITC rabbit anti–mouse IgG and analyzed with flow cytometry. The flow cytometry histogram shows that platelets are positive for CAR (graph representative of 4 experiments). (C) The presence of CAR on platelets was verified by human platelet mRNA analysis; 1.5% agarose gel showing RT-PCR of platelet-derived RNA amplifying 366-bp band from the CAR gene. Lane 1 is a 100-bp molecular weight ladder.

Platelets express CAR

An obvious candidate for adenovirus binding to platelets is the primary cellular attachment receptor CAR. Flow cytometric analysis showed strong expression of CAR on human platelets (Figure 6B). Human platelets showed an average of 72% and CAR-expressing HEK 293 cells an average of 88.4% positivity for the receptor (n = 4). To further substantiate this finding, we extracted RNA from human platelets and performed RT-PCR for the CAR gene. This demonstrated a 366-bp fragment corresponding to the expected human CAR product (Figure 6C). These studies indicate that adenovirus may bind platelets directly through CAR. Whether other platelet integrins are involved in this binding or in the internalization of the virus remains to be defined.

Discussion

This study has shown that the interaction between adenovirus and platelets leads to platelet activation and rapid exposure of P-selectin on the platelet surface. This in turn triggers the formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates through an interaction with the major P-selectin ligand, PSGL-1, on leukocytes. This interaction is essential to promote leukocyte rolling on the endothelium35 and also serves to slow platelets in an inflammatory setting because they also express small amounts of the ligand.6,37 The role of P-selectin in triggering accelerated platelet clearance has been documented previously with the transfusion of stored platelets.38 Clearance studies of chilled39,40 and stored platelets38 have demonstrated that the clustering of GPIb is a signal that mediates recognition of platelets by the scavenger macrophage receptor Mac-1 (αMβ2).41

In this study, we have also provided several pieces of evidence to indicate that endothelial cells are activated after adenovirus administration. There is increased VCAM-1 expression on cultured endothelial cells after in vitro incubation with the virus; there are substantial increases in total amounts of VWF and of ULVWF multimers in plasma following virus administration, and we have also documented an increased number of circulating endothelial cell-derived MPs. Endothelial cell activation and the associated up-regulation of adhesion molecules contribute to leukocyte or platelet-leukocyte aggregate rolling and transendothelial migration, a critical process for tissue macrophage influx. Whether adenovirus mediates endothelial cell activation directly or through activated platelets or platelet-leukocyte aggregates, or even PSGL-1+ MPs remains to be confirmed. Indeed, several of these mechanisms may work in combination.

Previous studies have documented the vector dose dependency of adenovirus-mediated thrombocytopenia (between 3.4 × 1011 and 6 × 1012 vp/kg).1,33 Our data now also show a critical role for VWF in mediating this pathology. This proposal is based on the high levels of VWF seen in the plasma and the appearance of ULVWF multimers seen following adenovirus injection. Elevated VWF levels have been documented within 6 hours following intravenous administration of 3.4 × 1011-3.8 × 1012 vp/kg adenovirus to Rhesus macaques.1 Based on our studies, similar effects were encountered following injection of 1 × 1011 vp/mouse (4 × 1012 vp/kg). It seems that a higher virus dose is required for VWF release and other adverse effects in mice and nonhuman primates compared to humans. Given that these effects are mediated by the adenoviral capsid, they are also very likely to occur with helper-dependent (gutless) adenoviral vectors.42

The data obtained from VWF KO mice further support an important role for VWF, because thrombocytopenia was not significant in these mice following virus injection. The lesser degree of thrombocytopenia (19% VWF KO versus 54% wild type [WT]) documented in these mice indicates that although VWF is apparently a major contributor to this process, it is not the only factor. We also do not know whether there is a direct relationship between the degree of thrombocytopenia and the plasma VWF level. P-selectin exposure on platelets is reduced following adenovirus administration in VWF KO mice and although some degree of thrombocytopenia is seen in these animals, platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation is abolished. This finding suggests that both VWF and P-selectin play contributory roles in these 2 processes.

Concomitant with thrombocytopenia, previous studies have reported other coagulation abnormalities such as an elevated plasma fibrinogen and prolonged clotting times in nonhuman primates following the injection of a comparable dose of adenovirus.1 In the current study, apart from the acute elevation of VWF and release of MPs that have potential procoagulant activities, we did not investigate additional coagulation parameters.

The complex interplay between platelets, endothelium, and leukocytes within an inflammatory setting makes it challenging to define the precise sequence of pathogenetic events following virus administration. A potential scenario starts with adenovirus activating platelets, followed by platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation, rolling of these aggregates on the endothelium, subsequent activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells, and MP release from the activated cells. Within the context of these events, the abnormal platelets will be recognized by the macrophage scavenger receptor and engulfed. Furthermore, the significant release of high-molecular-weight (HMW) forms of VWF along with the generation of cellular MPs provides a strong procoagulant stimulus that might result in an uncontrolled coagulopathy. Another potentially concurrent scenario may start with adenovirus activating endothelial cells, leading eventually to a similar chain of events.

The appearance of thrombocytopenia within 24 hours of adenovirus administration suggests that this is a component of the innate response to the virus. Studies of the kinetics of intravenously administered adenovirus indicate that 80% of virus is cleared within 24 hours by liver macrophages,43 the same period during which platelets disappear from the circulation. Because activated platelets are known to be cleared by macrophages,22 and we have shown evidence of adenovirus binding to platelets, it is possible that adenovirus or the activated platelets (or both) are cleared by a similar mechanism. The appearance of adenovirus particles within the liver macrophages as early as 10 minutes following tail vein injection43 and the rapid and significant macrophage death within 10 minutes of intravenous injection of the virus, shown recently by Manickan and coworkers, further support this possibility.44

The novel demonstration of CAR on platelets in this study provides strong evidence for direct adenovirus binding to platelets. The potential involvement of platelet integrins in virus binding and internalization requires further investigation.

Previous reports have shown that other microbes can bind platelets directly and induce P-selectin expression.45,46 This binding was shown to be responsible for the associated thrombocytopenia with particular involvement of platelet GPαIIbβ3.45 Internalization of bacteria and viruses has been seen in megakaryocytes and platelets47 and adenoviral particles have recently been documented inside platelets within 5 minutes of intravenous viral administration.48 Several candidate integrins might be involved in adenovirus binding and internalization. Platelets express αIIbβ3 integrin and other integrins (αvβ3, α5β1) that are known to bind the RGD motif in the virus penton base during the internalization process.49 Platelets also express αLβ2, which has been shown to bind adenovirus.50 Our data showing reduced platelet adhesion to fibronectin in the presence of the virus and a significant reduction of ADP-stimulated platelet adhesion further suggests that virus may bind platelets through one of these integrins.

Other potential candidates for adenovirus-platelet interactions are the Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Platelets express TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9, and TLR 4 has recently been shown to be an essential mediator of LPS-induced thrombocytopenia.51,52 It is likely that after initial adenovirus binding to platelets through CAR, integrins or other receptors are involved in the internalization of the virus.

In conclusion, adenovirus-induced thrombocytopenia is likely the result of a complex platelet-endothelial-leukocyte interplay. We have demonstrated that the virus binds to and activates platelets and activates endothelial cells either directly or through activated platelets, platelet-leukocyte aggregates, or possibly PSGL-1+ PMPs. VWF, together with P-selectin, are 2 key adhesion molecules that orchestrate this interplay. The activated platelets are subsequently removed by tissue macrophages possibly through a similar mechanism and timing for that involved in viral clearance.

Authorship

Contribution: M.O. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.L., I.M., and H.S.E. performed research; and D.L. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David Lillicrap, Richardson Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada K7L 3N6; e-mail: lillicrap@cliff.path.queensu.ca.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant (MOP-10912).

D.L. holds a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Hemostasis and is a Career Investigator of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. M.O. holds a NOVO NORDISK–Canadian Hemophilia Society (CHS) Fellowship in Congenital Bleeding Disorders.