Abstract

In this study, we characterized nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) subunit DNA binding in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) samples and demonstrated heterogeneity in basal and inducible NF-κB. However, all cases showed higher basal NF-κB than normal B cells. Subunit analysis revealed DNA binding of p50, Rel A, and c-Rel in primary CLL cells, and Rel A DNA binding was associated with in vitro survival (P = .01) with high white cell count (P = .01) and shorter lymphocyte doubling time (P = .01). NF-κB induction after in vitro stimulation with anti-IgM was associated with increased in vitro survival (P < .001) and expression of the signaling molecule ZAP-70 (P = .003). Prompted by these data, we evaluated the novel parthenolide analog, LC-1, in 54 CLL patient samples. LC-1 induced apoptosis in all the samples tested with a mean LD50 of 2.8 μM after 24 hours; normal B and T cells were significantly more resistant to its apoptotic effects (P < .001). Apoptosis was preceded by a marked loss of NF-κB DNA binding and sensitivity to LC-1 correlated with basal Rel A DNA binding (P = .03, r2 = 0.15). Furthermore, Rel A DNA binding was inversely correlated with sensitivity to fludarabine (P = .001, r2 = 0.3), implicating Rel A in fludarabine resistance. Taken together, these data indicate that Rel A represents an excellent therapeutic target for this incurable disease.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a malignancy characterized by the accumulation of CD5, CD19, and CD23 positive lymphocytes. Diagnosis is aided by the CLL immunophenotyping score which includes assessment of CD5 and CD23, FMC7, CD79b, and surface IgM.1 Although CLL is the commonest leukemia in the Western world, it manifests a very heterogeneous clinical course, with some patients having normal age-adjusted survival, whereas the median survival for those patients with advanced stage disease is only 3 years.2 The factors that contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of this disease are poorly understood, but decreased susceptibility to apoptosis3 and dysregulated proliferation have been implicated.4 Clinical studies have shown that high ZAP-70 expression, high CD38 expression, unmutated VH genes, and cytogenetic abnormalities (especially deletions of 11q and 17p) are all associated with a poor prognosis.5-9

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a collective name for a group of inducible homodimeric and heterodimeric transcription factors made up of members of the Rel family of DNA-binding proteins. In humans, this family is composed of c-Rel, Rel B, p50, p52, and Rel A (p65) which, when bound in the cytoplasm to inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) proteins, are inactive.10,11 Various factors, including ligation of CD40 or the B-cell receptor (BCR), result in proteosomal degradation of IκB releasing NF-κB, which then translocates to the nucleus.10,11 Once in the nucleus, NF-κB can enhance survival by inducing apoptosis inhibitory proteins, including inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), Fas-associated death domain (FADD)-like interleukin (IL)-1β–converting enzyme (FLICE), and FADD–like IL-1β–converting enzyme-inhibitory protein (FLIP).12-14 CLL cells have been reported to exhibit high constitutive NF-κB activation compared with normal B lymphocytes.15-17 Although the exact factors responsible for the constitutive expression of NF-κB are not fully resolved, many factors, including Akt activation, BCR signaling, CD40 ligation, IL-4, and B-cell activating factor (BAFF), have been shown to increase NF-κB activity and enhance CLL cell survival, with members of the Bcl-2 family being principal transcriptional targets.18-22 Several recent studies have demonstrated the proof of concept of the effectiveness of targeting NF-κB in hematologic malignancies, including CLL23,24 and acute myeloid leukemia.25,26

In this study, we first set out to determine the range of constitutive DNA binding of NF-κB within our patient cohort and to characterize the specific subunits of NF-κB in these primary CLL cells. We then went on to investigate the ability of freshly isolated CLL cells to induce NF-κB expression in response to BCR stimulation with anti-IgM and correlated our findings with proximal and distal signaling events, as defined by tyrosine phosphorylation, and changes in in vitro apoptosis. Basal and induced NF-κB was subsequently correlated with other known clinical prognostic markers. Finally, we investigated the effects of a novel NF-κB inhibitor LC-1 in primary CLL cells to identify potential biologic response markers to be used in an imminent clinical trial.

Methods

This study was approved by the South East Wales local research ethics committee (LREC #02/4806).

Patients

Peripheral blood samples from CLL patients were obtained with their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CLL was defined by clinical criteria as well as cellular morphology and the coexpression of CD19 and CD5 in lymphocytes simultaneously displaying restriction of light-chain rearrangement. Comprehensive clinical information, including treatment histories, was available for all patients, and none of the previously treated patients had received chemotherapy within 3 months before sample collection. Staging was based on the Binet classification system.27 The novel agent under investigation in these studies, LC-1, is a dimethylamino analog of parthenolide generated from the reaction of parthenolide with dimethylamine and was formulated as a water-soluble fumarate salt (by S.N. and P.A.C.). Details of the synthesis and structural identity of LC-1 are currently being prepared for publication. LC-1 was recently shown to selectively eradicate acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells in vitro via the induction of stress responses and the inhibition of NF-κB.25

ZAP-70 and CD38 expression

Cytoplasmic ZAP-70 expression was determined by using a modification of a previously published flow cytometry method.28 Cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Fix and Perm kit (Caltag, Botolph Claydon, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Permeabilized cells were labeled with the following antibodies: ZAP-70-Alexa fluor 488 (Caltag), CD3-phycoerythrin (PE), CD56-PE (BD Biosciences, Cowley, United Kingdom), and CD19-Allophycocyanin (APC) (Caltag). After appropriate lymphocyte gating, cytoplasmic ZAP-70 expression was determined in CD19+ CLL cells by gating on the CD3+ cells. Patients were considered to be ZAP-70 positive when more than or equal to 20% of the CD19+ CLL cells had equal or greater expression of ZAP-70 than the gated CD3+ cells. Cell surface expression of CD38 was examined by flow cytometry using a standard 3-color flow cytometry approach using CD5-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Dako UK, Ely, United Kingdom), CD38-PE (Caltag), and CD19-APC (Caltag). The cutoff point for CD38 positivity in CLL cells was more than or equal to 30%.

Intracellular expression of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins

CLL lymphocytes were analyzed by 3-color immunofluorescent staining using CD5 and CD19 surface antigenic markers in conjunction with a FITC-labeled phosphorylated-tyrosine antibody. The cells were analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and at least 10 000 events were acquired from each sample. The mean fluorescent intensity for phosphorylated tyrosine was calculated using WinMDI software (J. Trotter, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

VH gene mutation analysis

VH gene mutational status was determined for all patients using the method described previously.29 The resulting polymerase chain reaction products were sequenced and were considered unmutated if they showed 98% or greater homology with the closest germ line sequence.

Cell culture

Peripheral blood lymphocytes from 54 CLL patients and 10 age-matched normal control patients were isolated from freshly collected blood samples by density centrifugation. B cells were subsequently positively isolated using CD19+ Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom), and the beads were then detached using DETACHaBEAD CD19 reagent (Invitrogen). The purity of the CD5+/CD19+ CLL cells was more than 96% and normal B cells (CD19+) more than 90% as assessed by flow cytometry. CD19+ lymphocytes were then cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in the presence of parthenolide or LC-1 (10−7 to 10−5 M) for up to 48 hours. Parallel experiments using fludarabine (10−7 to 10−5 M) were also performed to assess the comparative intrasample and intersample in vitro cytotoxicity. Control cultures were also carried out to which no drug was added to normal and leukemic lymphocytes. Cells were subsequently harvested by centrifugation and were analyzed by flow cytometry. Experiments were performed in either duplicate or triplicate.

Measurement of apoptosis by annexin V/propidium iodide dual labeling

Apoptosis was assessed by dual-color immunofluorescent flow cytometry as described previously. Briefly, 106 cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline and were incubated for 15 minutes in the dark in 200 μL of binding buffer contain 4 μL annexin V-FITC and 10 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Caltag). Cells were analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Caspase-3 activation assay

CLL cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere in the presence of LC-1 (10−7 to 10−5 M) for 24 hours. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation and labeled with CD19-APC antibody. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in the presence of the PhiPhiLux G1D2 substrate (Calbiochem, Nottingham, United Kingdom). The substrate contains 2 fluorophores separated by a quenching linker sequence that is cleaved by active caspase-3. Once cleaved, the resulting products fluoresce green and can be quantified using flow cytometry.

NF-κB detection by electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were generated from CLL cells (> 90% CD5+/CD19+ lymphocytes as assessed by flow cytometry) using a modification of a previously described protocol.30 The protein from nuclear extracts was quantified by the Bradford method. Equivalent quantities of nuclear protein (1-4 μg) were incubated with 32P radiolabeled probes, generated by T4 polynucleotide kinase labeling. The probes used corresponded to a consensus NF-κB binding site (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom). The binding reaction was performed in binding buffer (4% glycerol, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/mL nuclease-free bovine serum albumin, 50 mM dithiothreitol) with the addition of 2 ng of poly dIdC (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) for 30 minutes at room temperature before separation of protein DNA complexes using a 4% native acrylamide gel. NF-κB DNA binding was quantified by scanning densitometry. NF-κB inhibition studies were also carried out in CLL cells exposed to LC-1 for 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours.

Rel A NF-κB DNA binding detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Nuclear extracts from CLL patients and B and T lymphocytes derived from age-matched controls were assayed for Rel A activity with a TransAM NF-κB transcripton factor assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The principle behind the assay involves the capture of NF-κB by an oligonucleotide containing an NF-κB consensus site, which is immobilized in each well of a 96-well plate. The Rel A subunit was subsequently detected using a Rel A-specific antibody. The normal lymphocytes were cell sorted (purity > 95% for each lymphocyte population), and these samples were compared with the CLL samples. The optical density reading at 450 nm (OD450) was read on a microtiter plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom). OD450 values were converted into nanograms per microgram of nuclear extract for each sample tested from a standard curve constructed using known quantities of recombinant Rel A NF-κB.

Statistical analysis

All of the datasets derived in this study were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Where the data were deemed to be Gaussian or approximately Gaussian, the datasets were compared using parametric assays (equal variance or paired Student t test); in all other cases, a Mann-Whitney test was used. Correlation coefficients were calculated from least squares linear regression plots, and LD50 values were calculated from line of best-fit analysis of the sigmoidal dose response curves. All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

NF-κB is heterogeneous in CLL patient samples

CLL cells have been shown to exhibit high levels of nuclear NF-κB compared with nonmalignant B cells.16,31 However, a detailed analysis of the variation in levels of NF-κB across multiple patients or a dissection of the constituent subunits in primary CLL cells has not been previously described. We investigated NF-κB DNA binding in 30 unselected CLL patients using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). All of the isolated mononuclear samples tested had more than 90% CD5+/CD19+ lymphocytes as assessed by flow cytometry. We chose 2 cell lines as reference for the assay: BL41, a Burkitt lymphoma line with relatively low NF-κB activity, and IARC-171, an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) immortalized line derived from the same patient. EBV activates NF-κB during B-cell immortalization, so IARC-171 cells represent a positive control for a B-cell high in NF-κB.

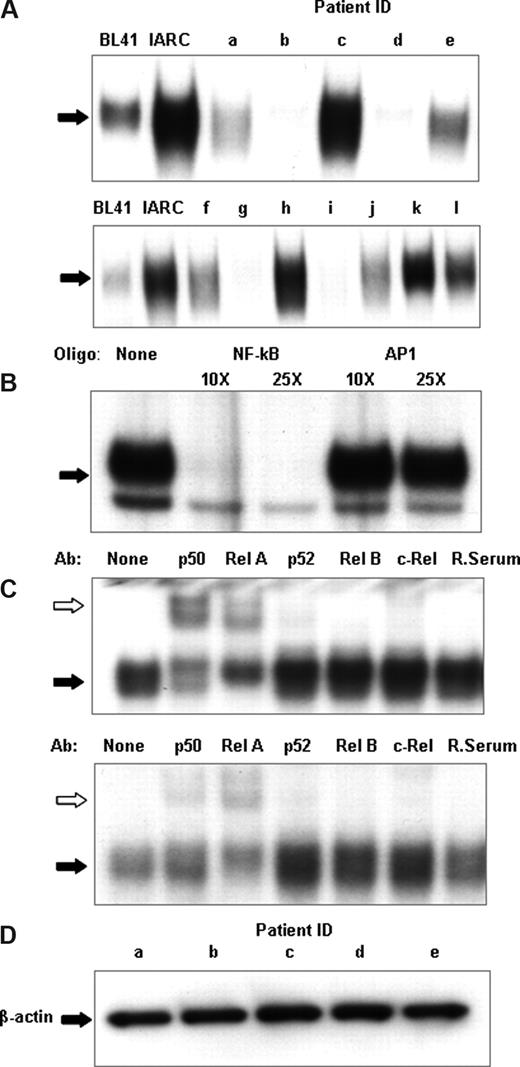

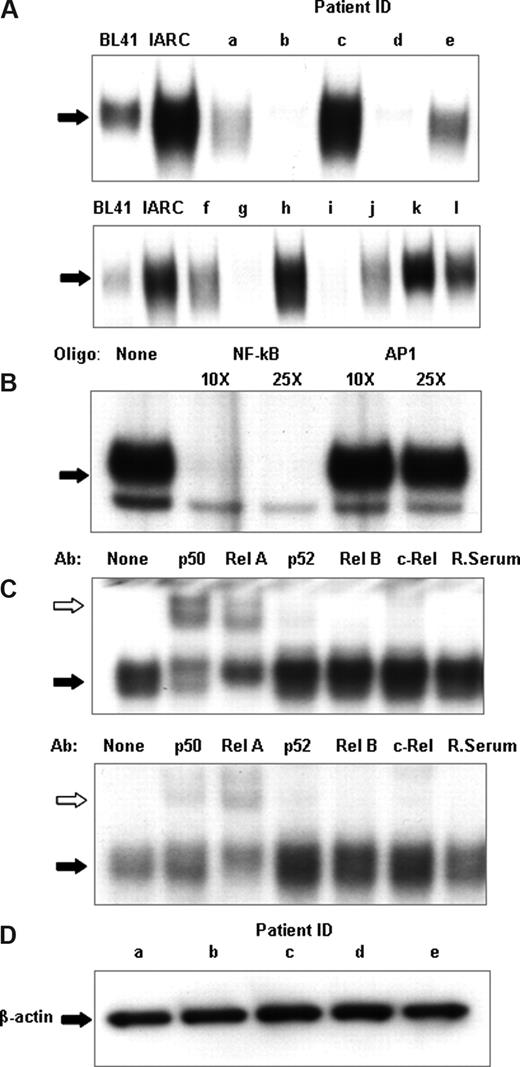

Figure 1A shows a representative sample of nuclear extracts derived from 12 patients demonstrating the differential expression of NF-κB DNA binding. DNA binding varied from almost undetectable (patients b, d, g, and i) to levels comparable to or higher than those found in the EBV-immortalized cells (patients c, h, and k) with other samples showing intermediate NF-κB DNA binding. The specificity of the NF-κB binding was confirmed by an EMSA cold competitor assay (Figure 1B). A nonradioactively labeled NF-κB DNA oligonucleotide eliminated binding, whereas an oligonucleotide for another transcription factor, AP1, left DNA binding unaffected.

CLL patients show heterogeneity of NF-κB DNA binding. (A) NF-κB DNA binding activity in cell nuclear extracts was measured using electrophoretic mobility shift assays. An oligonucleotide corresponding to the consensus sequence to NF-κB was radiolabeled and incubated with 2 μg nuclear extract. The DNA-polynucleotide complex was restored by electrophoresis in a 4% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate/EDTA buffer. The gels were dried, and protein binding was visualized by autoradiography. To demonstrate specificity, a cold competitor assay was performed on 2 μg nuclear extracts of CLL patient k (B). Cold, nonradiolabeled NF-κB and a nonspecific oligonucleotide, AP1, was added at 10× and 25× the concentration of radiolabeled NF-κB and incubated for 30 minutes, before radiolabeled NF-κB incubation. (C) For qualitative analysis of NF-κB subunits, super-shift analysis was performed on NF-κB using p50, Rel A, p52, Rel B, and c-Rel antibodies and normal rabbit sera; 2 μg nuclear extracts from CLL nuclear extracts were used for these experiments. The different lanes marked, none, p50, Rel A, p52, Rel B, c-Rel, and Rab ser (pre-immune rabbit sera) represent incubation with different antibodies. They were then incubated with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the consensus sequence of NF-κB for 30 minutes. Ab indicates the different antibodies used; None, no antibody was incubated. White arrows indicate the antibody-protein-DNA complexes; black arrows, the protein-DNA complexes. Free DNA has been omitted. (D) Nuclear extracts from sample a through sample e were Western blotted for β-actin to assess the relative integrity of the nuclear protein extracts between samples and to confirm equal loading of nuclear proteins in the experiments.

CLL patients show heterogeneity of NF-κB DNA binding. (A) NF-κB DNA binding activity in cell nuclear extracts was measured using electrophoretic mobility shift assays. An oligonucleotide corresponding to the consensus sequence to NF-κB was radiolabeled and incubated with 2 μg nuclear extract. The DNA-polynucleotide complex was restored by electrophoresis in a 4% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate/EDTA buffer. The gels were dried, and protein binding was visualized by autoradiography. To demonstrate specificity, a cold competitor assay was performed on 2 μg nuclear extracts of CLL patient k (B). Cold, nonradiolabeled NF-κB and a nonspecific oligonucleotide, AP1, was added at 10× and 25× the concentration of radiolabeled NF-κB and incubated for 30 minutes, before radiolabeled NF-κB incubation. (C) For qualitative analysis of NF-κB subunits, super-shift analysis was performed on NF-κB using p50, Rel A, p52, Rel B, and c-Rel antibodies and normal rabbit sera; 2 μg nuclear extracts from CLL nuclear extracts were used for these experiments. The different lanes marked, none, p50, Rel A, p52, Rel B, c-Rel, and Rab ser (pre-immune rabbit sera) represent incubation with different antibodies. They were then incubated with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the consensus sequence of NF-κB for 30 minutes. Ab indicates the different antibodies used; None, no antibody was incubated. White arrows indicate the antibody-protein-DNA complexes; black arrows, the protein-DNA complexes. Free DNA has been omitted. (D) Nuclear extracts from sample a through sample e were Western blotted for β-actin to assess the relative integrity of the nuclear protein extracts between samples and to confirm equal loading of nuclear proteins in the experiments.

Specific NF-κB subunits have different abilities to activate gene expression. For this reason, the next step of our study was a qualitative analysis of individual NF-κB subunits in leukemic CLL B cells. For this we performed super-shift EMSA using antibodies against specific NF-κB proteins (Rel A, p50, p52, c-Rel, and Rel-B) with nuclear extracts prepared from CLL cells (Figure 1C). A rabbit serum control was used in each case. Rel A, p50, and c-Rel subunits were detected in all the samples tested, as evidenced by shifts in their respective bands following antibody binding, but with marked variation in the amounts of each in the different patient samples.

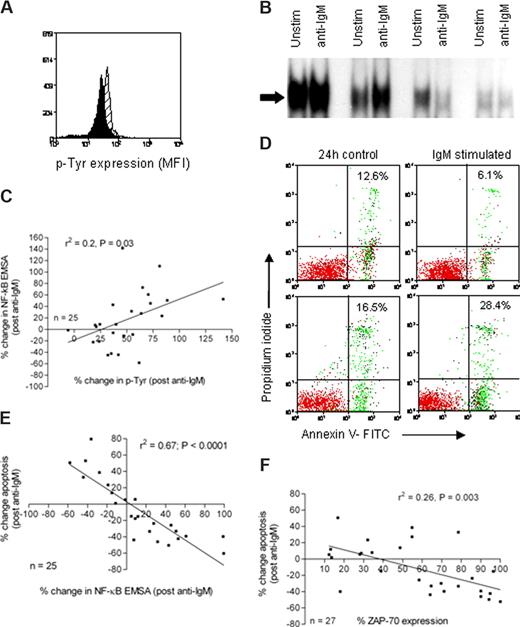

NF-κB is a key link between BCR signals and cell apoptosis

We next investigated the ability of CLL cells to induce NF-κB as a downstream consequence of BCR ligation. Proximal signaling was assessed by quantifying protein tyrosine phosphorylation before and after cross-linking of the BCR. Subsequently, NF-κB induction and cellular apoptosis were measured in paired CLL samples. Freshly isolated CLL cells from 24 patients were stimulated with anti-IgM for 15 minutes, and protein tyrosine phosphorylation was analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 2A shows a typical example of an overlaid histogram plot of tyrosine phosphorylation in CLL cells derived from an individual patient before and after stimulation with anti-IgM. Using the same experimental paradigm, NF-κB was analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift in samples with and without BCR stimulation. Figure 2B shows representative data from 4 different patient samples. To analyze the effects of BCR stimulation on NF-κB nuclear expression and because of the inherent variation from experiment to experiment when using EMSA, we internally controlled the experiments by expressing the data as percentage change in NF-κB after BCR stimulation (stimulated − control/control × 100). We identified a correlation (r2 = 0.2, P < .05) between the percentage change in protein tyrosine phosphorylation and the percentage change in NF-κB (Figure 2C). We observed that anti-IgM treatment of CLL cells caused an increase in apoptosis in some samples and a decrease in apoptosis in others (Figure 2D). Importantly, this was reflected by a change in NF-κB; and when data from 24 patients were analyzed, a striking inverse correlation (r2 = 0.67, P < .001) was detected in which an increase in NF-κB correlated with a reduction in cellular apoptosis (Figure 2E). Therefore, the data suggest that NF-κB is a key regulator of in vitro CLL cell survival. Furthermore, the ability of CLL cells to induce NF-κB DNA binding was closely associated with the expression of ZAP-70 (Figure 2F). These data support a previous report finding that forced overexpression of ZAP-70 in CLL cells enhanced BCR signaling.32

Analysis of proximal and distal signaling events in CLL cells derived from CLL patients. (A) CLL cells were left untreated (black histogram) or treated with anti-IgM (gray histogram) for 15 minutes. They were then fixed and stained with an FITC-conjugated antiphosphotyrosine antibody (PY20), and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. (B) CLL cells were left untreated or treated with anti-IgM as indicated for 1 hour. Nuclear extracts were prepared and NF-κB activity was evaluated by electrophoretic mobility shift assay; only the shifted bands are shown. (C) The percentage change in protein tyrosine phosphorylation and NF-κB activity (before and after ligation with anti-IgM) was calculated. The percentage change in NF-κB correlated with percentage change in protein tyrosine phosphorylation (r2 = 0.2, P = .03). (D) Cell apoptosis was measured after 24 hours using annexin V binding and PI exclusion in untreated CLL cells and cells treated with anti-IgM. The percentages shown in the upper right quadrant of each dot plot denote the total percentage of apoptotic cells in the upper and lower right quadrants. (E) The relationship between the percentage change in NF-κB and the percentage change in apoptosis was investigated, and a significant inverse correlation was detected (r2 = 0.67, P < .001). (F) ZAP-70 expression was associated with NF-κB activation after exposure to anti-IgM (P = .003).

Analysis of proximal and distal signaling events in CLL cells derived from CLL patients. (A) CLL cells were left untreated (black histogram) or treated with anti-IgM (gray histogram) for 15 minutes. They were then fixed and stained with an FITC-conjugated antiphosphotyrosine antibody (PY20), and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. (B) CLL cells were left untreated or treated with anti-IgM as indicated for 1 hour. Nuclear extracts were prepared and NF-κB activity was evaluated by electrophoretic mobility shift assay; only the shifted bands are shown. (C) The percentage change in protein tyrosine phosphorylation and NF-κB activity (before and after ligation with anti-IgM) was calculated. The percentage change in NF-κB correlated with percentage change in protein tyrosine phosphorylation (r2 = 0.2, P = .03). (D) Cell apoptosis was measured after 24 hours using annexin V binding and PI exclusion in untreated CLL cells and cells treated with anti-IgM. The percentages shown in the upper right quadrant of each dot plot denote the total percentage of apoptotic cells in the upper and lower right quadrants. (E) The relationship between the percentage change in NF-κB and the percentage change in apoptosis was investigated, and a significant inverse correlation was detected (r2 = 0.67, P < .001). (F) ZAP-70 expression was associated with NF-κB activation after exposure to anti-IgM (P = .003).

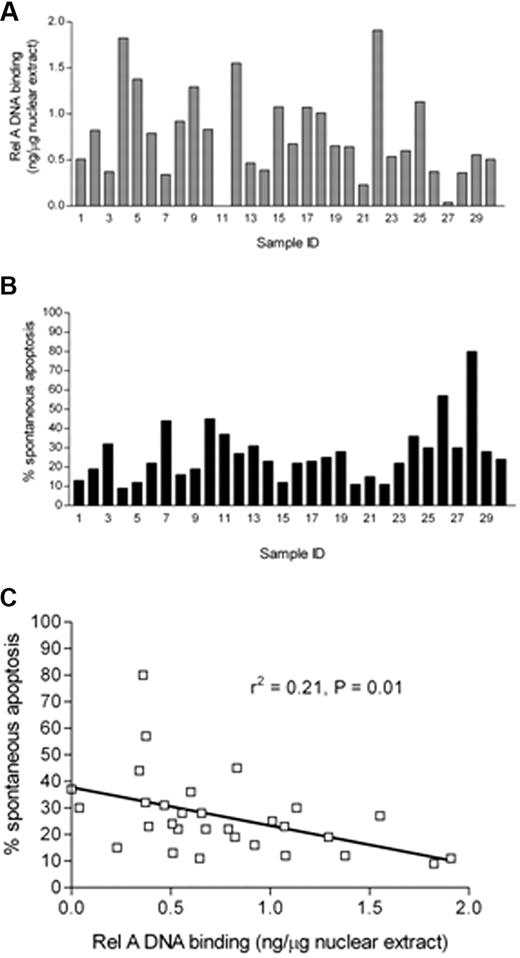

The Rel A NF-κB subunit DNA binding shows marked variability, which correlates with CLL cell survival

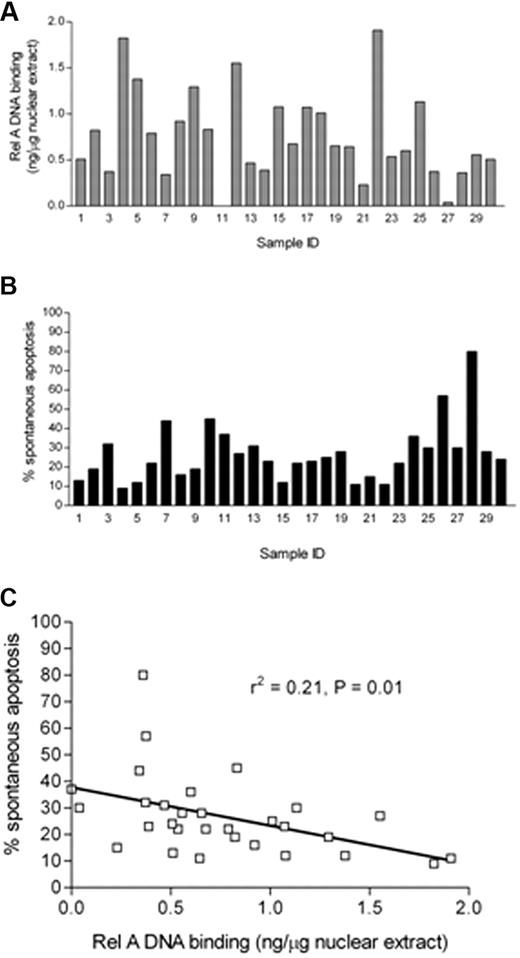

The variation in basal NF-κB prompted us to quantify the Rel A component of the complex. This component was of particular interest because it contains a transactivation domain absent in the p50 component of NF-κB.33 Using a DNA binding ELISA-based method, we analyzed Rel A in nuclear extracts derived from freshly isolated CLL cells. We generated a standard curve (data not shown) using recombinant Rel A, which showed excellent linearity (r2 = 0.98), and this allowed us to express the values for Rel A as nanograms per microgram of nuclear extract. Data from 30 patients are shown in Figure 3A, which shows the variability in Rel A from undetectable levels up to 1.909 ng/μg of nuclear extract. Samples derived from normal B and T lymphocytes had levels of Rel A below the threshold of detection (data not shown). In parallel experiments, samples from each of these 30 patients were also analyzed for in vitro apoptosis after 48 hours in cell culture using annexin V and PI labeling (Figure 3B); again, the samples showed a wide variation ranging from 9% to 80%. We then compared the ex vivo Rel A DNA binding activity of each sample with their propensity to undergo in vitro apoptosis after 48 hours in culture. Figure 3C shows that there was a significant inverse correlation between CLL cell in vitro apoptosis and Rel A DNA binding activity (r2 = 0.21, P = .01).

Quantitative analysis of rel A DNA binding in CLL B cells and its relationship to apoptosis. (A) Subunit-specific Rel A ELISA (Active Motif) assays were performed using 2 μg of nuclear extracts derived from 30 freshly isolated ex vivo CLL samples. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Results were compared with a standard curve generated using recombinant protein that allowed the calculation of the amount of p65 present in CLL cells expressed relative to total nuclear protein from CLL patient samples. (B) Parallel experiments were performed in which aliquots of CLL B cells derived from the same 30 CLL patients were set up in in vitro culture for 48 hours, and spontaneous apoptosis was then measured using annexin V and PI staining. FACS plots were analyzed using Summit 4.3 software (Dako). Percentage apoptosis was defined as the total annexin V+ cells (PI+ and PI−) after 48 hours in culture. (C) The level of apoptosis showed a significant negative correlation with nuclear Rel A DNA binding activity in the nucleus of freshly isolated CLL cells.

Quantitative analysis of rel A DNA binding in CLL B cells and its relationship to apoptosis. (A) Subunit-specific Rel A ELISA (Active Motif) assays were performed using 2 μg of nuclear extracts derived from 30 freshly isolated ex vivo CLL samples. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Results were compared with a standard curve generated using recombinant protein that allowed the calculation of the amount of p65 present in CLL cells expressed relative to total nuclear protein from CLL patient samples. (B) Parallel experiments were performed in which aliquots of CLL B cells derived from the same 30 CLL patients were set up in in vitro culture for 48 hours, and spontaneous apoptosis was then measured using annexin V and PI staining. FACS plots were analyzed using Summit 4.3 software (Dako). Percentage apoptosis was defined as the total annexin V+ cells (PI+ and PI−) after 48 hours in culture. (C) The level of apoptosis showed a significant negative correlation with nuclear Rel A DNA binding activity in the nucleus of freshly isolated CLL cells.

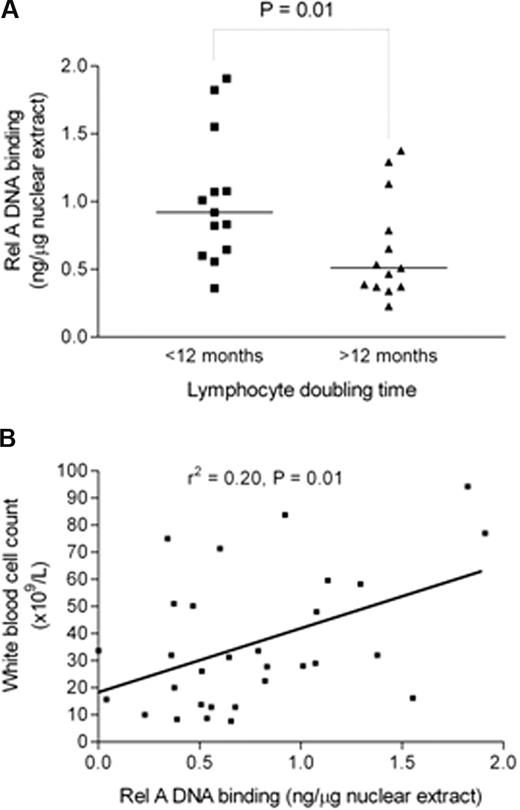

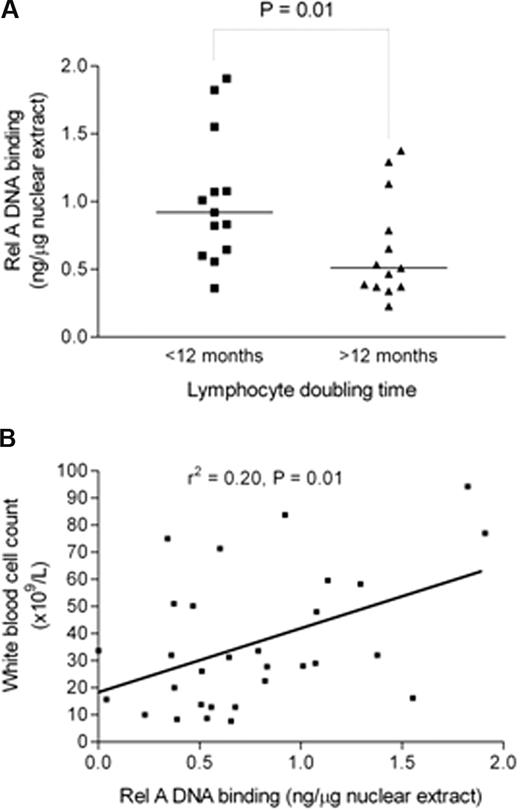

Basal Rel A DNA binding is higher in patients with shorter lymphocyte doubling times and positively correlates with total white cell count

Having implicated NF-κB subunit Rel A as important for in vitro CLL cell survival, we next investigated Rel A in relation to clinical markers of tumor burden and disease activity in CLL. Clinical laboratory parameters, such as lymphocyte count or total white cell count, bone marrow infiltration pattern, and lymphocyte doubling time (LDT), reflect the tumor burden and/or disease activity in CLL.34 Rel A DNA binding was measured using subunit-specific ELISA in 30 freshly isolated patient samples and results were compared with LDT, calculated from patient records, and total white cell count on the date of sample collection. Rel A was significantly higher in patients with an LDT less than 12 months (P < .01; Figure 4A). There was also a significant correlation (r2 = 0.2, P = .01) between Rel A DNA binding and total white cell count (Figure 4B). Taken together, these data suggest that Rel A contributes to tumor burden and disease activity in CLL. It is of interest that basal Rel A expression did not correlate with VH gene mutation status, CD38 expression, or ZAP-70 expression in this cohort.

Rel A DNA binding is higher in samples from patients with shorter lymphocyte doubling time and positively correlates with total white cell count. (A) Rel A levels were measured by DNA binding ELISA (Active Motif) and were compared in patients with a lymphocyte doubling time above or below 12 months. Patients with lymphocyte doubling time of less than 12 months show a significantly higher level of Rel A (P < .01). (B) There was a significant positive correlation between Rel A DNA binding activity in cells from patients and their total white cell count (r2 = 0.2, P = .01).

Rel A DNA binding is higher in samples from patients with shorter lymphocyte doubling time and positively correlates with total white cell count. (A) Rel A levels were measured by DNA binding ELISA (Active Motif) and were compared in patients with a lymphocyte doubling time above or below 12 months. Patients with lymphocyte doubling time of less than 12 months show a significantly higher level of Rel A (P < .01). (B) There was a significant positive correlation between Rel A DNA binding activity in cells from patients and their total white cell count (r2 = 0.2, P = .01).

LC-1 inhibits NF-κB and induces apoptosis of CLL cells

We next investigated the in vitro effects of a putative NF-κB inhibitor, LC-1, in 54 freshly isolated CLL patient samples. LC-1 is a derivative of the sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide, which has been shown to selectively kill CLL cells in vitro23 and targets the transcription factor NF-κB. This has been shown to be mediated through the inhibition of IκB kinase in HeLa cells,35 but this has not been definitively shown in primary CLL cells. Parthenolide has poor solubility and unfavorable pharmacokinetics; in contrast, LC-1 has superior pharmacokinetic properties and more than 1000-fold greater solubility than the parent compound and therefore represents an excellent candidate drug. As part of our evaluation of the molecule, we wanted to establish whether Rel A DNA binding could predict for in vitro sensitivity to LC-1 and fludarabine.

CLL cells were incubated with a range of concentrations of LC-1 or parthenolide (0.1-10 μM) for up to 48 hours, and apoptosis was quantified using annexin V and PI labeling. Both LC-1 (Figure 5A) and parthenolide (data not shown) induced apoptosis was dose- and time-dependent. The 24-hour mean LD50 value (± SD) for LC-1 in the 54 CLL patient samples tested was 2.8 μM (± 1.0 μM). LC-1-induced apoptosis was associated with a concomitant increase in the activation of caspase-3 (not shown). LC-1 and parthenolide showed a time- and concentration-dependent increase in apoptosis with equimolar concentrations of LC-1 significantly more cytotoxic than parthenolide at both 24 hours (P = .02) and 48 hours (P = .03). Importantly, the mean LC-1 LD50 value was significantly lower for CLL cells than that derived from normal B and T cells and the T-cell derived from CLL patients (Figure 5B). This suggests a specificity of this inhibitor for leukemic cells. Figure 5C demonstrates that LC-1 inhibits NF-κB DNA binding in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibition is detectable at 4 hours and precedes any loss of cell viability; hence, the effect is not merely a consequence of cell death induction.

LC-1 and parthenolide induce time- and concentration-dependent apoptosis in primary CLL cells and follow the reduction of NF-κB. (A) CD19+ CLL cells were treated with LC-1 (0-10 μM) for 24 and 48 hours and were then labeled with annexin V and PI. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as the sum of the upper and lower right quadrants (ie, annexin V+/PI+ and annexin V+/PI−). A concentration-dependent increase in annexin V+ cells was observed. (B) Normal CD19+ B lymphocytes derived from nonleukemic, age-matched, donors were more than 2-fold less sensitive to the apoptotic effects of LC-1 than CD19+ CLL cells (P < .001). (C) CLL cells were treated with LC-1 (0-5 μM) for 4 hours before harvesting and nuclear protein extraction. EMSA analysis (top panel) and quantification by densitometry (middle panel) revealed a dose-dependent decrease in NF-κB activity in the absence of detectable apoptosis (bottom panel) measured by annexin V and PI.

LC-1 and parthenolide induce time- and concentration-dependent apoptosis in primary CLL cells and follow the reduction of NF-κB. (A) CD19+ CLL cells were treated with LC-1 (0-10 μM) for 24 and 48 hours and were then labeled with annexin V and PI. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as the sum of the upper and lower right quadrants (ie, annexin V+/PI+ and annexin V+/PI−). A concentration-dependent increase in annexin V+ cells was observed. (B) Normal CD19+ B lymphocytes derived from nonleukemic, age-matched, donors were more than 2-fold less sensitive to the apoptotic effects of LC-1 than CD19+ CLL cells (P < .001). (C) CLL cells were treated with LC-1 (0-5 μM) for 4 hours before harvesting and nuclear protein extraction. EMSA analysis (top panel) and quantification by densitometry (middle panel) revealed a dose-dependent decrease in NF-κB activity in the absence of detectable apoptosis (bottom panel) measured by annexin V and PI.

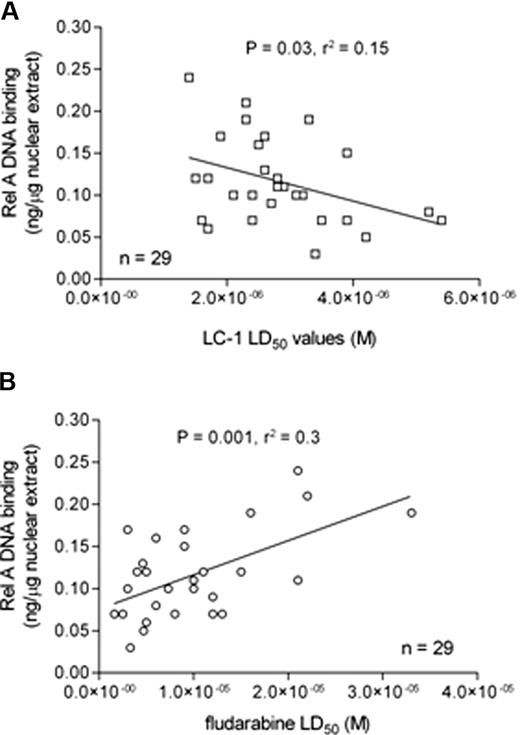

Correlation between Rel A DNA binding and in vitro drug sensitivity

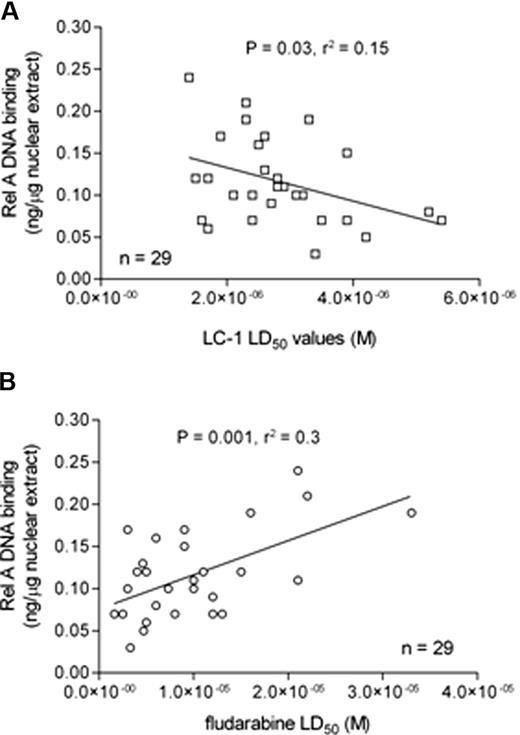

We next examined the relationship between Rel A DNA binding and sensitivity to LC-1 and the purine nucleoside analog, fludarabine. Basal nuclear Rel A DNA binding was inversely correlated with LC-1 LD50 values (Figure 6A), suggesting that CLL cells that relatively overexpress Rel A are more dependent on NF-κB signaling to maintain in vitro cell viability. In contrast, fludarabine LD50 values positively correlated with nuclear Rel A expression (Figure 6B), suggesting that drug resistance to fludarabine may be mediated, at least in part, through the transcriptional effects of Rel A.

Rel A DNA binding correlates with sensitivity to LC-1 and resistance to fludarabine. (A) Sensitivity to LC-1 was inversely correlated with nuclear Rel A NF-κB DNA binding. (B) In contrast, in vitro resistance to fludarabine was positively correlated with nuclear Rel A NF-κB DNA binding.

Rel A DNA binding correlates with sensitivity to LC-1 and resistance to fludarabine. (A) Sensitivity to LC-1 was inversely correlated with nuclear Rel A NF-κB DNA binding. (B) In contrast, in vitro resistance to fludarabine was positively correlated with nuclear Rel A NF-κB DNA binding.

Discussion

One of the key achievements of this study was to move beyond the relatively simplistic concept that NF-κB is elevated in CLL patient samples toward a more detailed qualitative and quantitative study of this important group of transcription factors. We have shown that CLL cells typically express p50, Rel A, and c-Rel but in various amounts. In agreement with previous reports,15,16 even the CLL samples that had low NF-κB expression had higher levels than primary B cells in which no NF-κB could be detected by EMSA or Rel A-specific ELISA. NF-κB has been implicated in tumorigenesis and survival of a growing list of leukemias and lymphomas, including Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and chronic myeloid leukemia.10 However, no previous study has quantified NF-κB subunits in primary patient samples. Furthermore, this is the first study to relate this quantification to in vitro cell survival, tumor burden, and disease activity (LDT), thus demonstrating that an individual component of the NF-κB complex can contribute to the regulation of human disease.

This study builds directly on others that have shown NF-κB provides prosurvival signals to several different cell types. Both primary cancer tissues and cell culture models of these cancers exhibit constitutive activated NF-κB and inhibition of this activity by overexpression of IκB or pharmacologic agents induces in vitro apoptosis.24,36,37 Our data, correlating Rel A with spontaneous in vitro apoptosis, show that the variation in Rel A can explain 21% (r2 = 0.21) of the variation in apoptosis of CLL B cells. This raises 2 important questions: (1) what genes are regulated by Rel A to promote increased CLL cell survival? and (2) what molecules are regulating the other 79% of CLL cell survival? Both of these questions are currently under investigation.

Previous work has suggested that the majority of CLL cells with unmutated VH genes respond to BCR stimulation, whereas the majority of mutated cases do not. Furthermore, ZAP-70 expression appears to enhance this proximal signaling process.32,38 However, the downstream targets of BCR signaling in CLL cells have not been fully elucidated. Given that a downstream target of BCR signaling in normal B lymphocytes is NF-κB,20,39 we assessed the ability of CLL cells to induce NF-κB after stimulation with anti-IgM. We found an association between ZAP-70 expression and the ability of CLL cells to activate NF-κB. Furthermore, the magnitude of the change in NF-κB after stimulation with anti-IgM was associated with the suppression of in vitro apoptosis. Taken together, these data suggest that the ability to induce NF-κB may be a critical factor in the pathology of CLL and present a rationale for the poor prognosis associated with ZAP-70 expression.

We went on to evaluate the relationship between basal Rel A DNA binding and prognostic markers. Surprisingly, we found no significant correlation between Rel A and VH gene mutation status, CD38 expression, or ZAP-70 expression. In contrast, we did find a clear association between elevated Rel A, short LDT, and high white cell count. These markers of disease activity and tumor burden have been shown to correlate with overall survival in several studies and reinforce the importance of this transcription factor in CLL.40-42 We hypothesize that the lack of correlation between basal Rel A DNA binding and VH gene status, CD38, and ZAP-70 is because these factors contribute to the ability of CLL cells to induce NF-κB after stimulation rather than constitutive expression. In support of this, the data presented in this manuscript clearly show an association between ZAP-70 expression and the ability of CLL cells to activate NF-κB after stimulation with anti-IgM. Given the association between basal Rel A and high white cell count and LDT and the striking association between ZAP-70 and the ability to induce NF-κB, it seems that both basal and inducible NF-κB is important in the pathology of CLL.

Finally, this report represents the first preclinical evaluation of LC-1, a novel dimethylamino analog of parthenolide, in primary human CLL cells. LC-1 was more than 2-fold more potent in vitro than molar equivalents of parthenolide and has greater solubility and superior pharmacokinetics than the parent compound. Interestingly, LC-1 uniformly inhibited nuclear NF-κB activity in all the CLL samples tested, but strikingly cells derived from patients with the highest nuclear NF-κB activity were most sensitive to LC-1–induced apoptosis, suggesting some aspect of preferential NF-κB “oncogene addiction.” Given the heterogeneity of NF-κB in the CLL patient cohort and our observation that Rel A is elevated in patients with a shorter lymphocyte doubling time, this study indicates that targeting NF-κB could be most valuable for patients with a poor prognosis. In this context, it is noteworthy that several other NF-κB inhibitors have also shown promise in preclinical evaluation in primary CLL cells.23,24,43-46

The development of drug resistance is a major clinical problem in CLL.47-51 Therefore, it is important to note that sensitivity to LC-1 was undiminished in patients who had received prior chemotherapy. Furthermore, 7 patients included in this study had marked clinical resistance to fludarabine but retained in vitro sensitivity to LC-1. In addition, a patient with a known p53 deletion showed similar sensitivity to LC-1 but, in contrast, showed marked in vitro resistance to fludarabine. At present, only 3 agents, alemtuzumab, flavopiridol, and corticosteroids, appear to retain clinical activity in patients with p53 deletions/mutations so new effective agents are urgently required for the treatment of these clinically problematic subsets.52-60 LC-1, with its unique cytotoxic profile, could be considered for clinical trials for the treatment of poor prognosis CLL patients, including those with clinical resistance to fludarabine.

In conclusion, the data presented highlight the importance of both constitutive and inducible NF-κB in CLL. In particular, it indicates that the specific NF-κB subunit, Rel A, is associated with survival and possibly proliferation of CLL cells. The regulation of this transcription factor is complex and requires further elucidation to understand the critical signaling events that control NF-κB activation in vivo. However, our data suggest that Rel A may contribute to fludarabine resistance; therefore, molecules designed to inhibit NF-κB, and Rel A in particular, may be clinically useful both as single agents and in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Bill Matthews of Leuchemix, Inc for permission to carry out the LC-1 studies.

This work was supported in part by grants from Leukemia Research (United Kingdom), the Leukemia Research Appeal for Wales, the Welsh Bone Marrow Transplant Research Fund, and Tenovus, the Cancer Charity. S.H. is a Leukemia Research (United Kingdom) Clinical Research Fellow.

Authorship

Contribution: S.H. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; S.A. performed research; T.T.L. performed research and analyzed data; M.C., C.J., and M.L.G. performed research; C.T.J. contributed vital new reagents and revised the manuscript; S.N., P.A.C., and A.K.B. contributed vital reagents; G.P. contributed vital new reagents and revised the manuscript; C.F. contributed vital new reagents, analyzed data, and revised the manuscript; C.R. contributed vital new reagents and revised the manuscript; P.B. and C.P. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.T.J., S.N., and P.A.C. hold stock in Leuchemix, Inc. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Chris Pepper, Department of Haematology, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, United Kingdom; e-mail: peppercj@cf.ac.uk.