To the editor:

We read with interest the paper from Whitman and colleagues1 reporting an adverse impact on disease-free survival of FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain (FLT3/TKD) mutations in 19 of 217 patients with normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia (AML). This contrasts with our data where the presence of FLT3/TKD mutations in 127 of 1107 nonacute promyelocytic leukemia patients was associated with a significantly better prognosis.2 Discordant results between series may arise by chance, particularly where the number of cases is relatively small. However, they should also raise the possibility of differences in patient cohorts or treatment received.

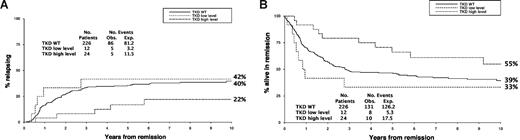

The Whitman cohort was restricted to patients with a normal karyotype, and those with an FLT3/internal tandem duplication (ITD), a recognized poor prognostic factor, were excluded. We found no evidence of heterogeneity in outcome if patients were further stratified for presence or absence of an FLT3/ITD, but of 226 normal karyotype FLT3/ITD− patients in our cohort, 38 were FLT3/TKD+; 25 had a higher mutant level (median 41% of total FLT3 alleles, range 25%-60%) and 13 a lower mutant level (median 7%, range 3%-23%) indicative of an FLT3/TKD in only a subset of cells. The cumulative incidence of relapse for FLT3/TKD+ patients with higher or lower mutant level compared with wild-type (WT) patients was similar to our larger cohort, with only a higher mutant level being associated with a significantly lower relapse rate (Figure 1A). The difference in relapse rate between the groups was not quite significant (P = .07 for trend), but this is not surprising as there were only 24 patients with a higher level TKD. Curves for disease-free survival are shown in Figure 1B. Importantly, the results are incompatible with the presence of an FLT3/TKD imparting a worse prognosis, as found by Whitman and colleagues.

Outcome in FLT3/ITD-negative patients with a normal karyotype, stratified by FLT3/TKD status. (A) Cumulative incidence of relapse. (B) Disease-free survival.

Outcome in FLT3/ITD-negative patients with a normal karyotype, stratified by FLT3/TKD status. (A) Cumulative incidence of relapse. (B) Disease-free survival.

This necessitates a further search for differences in the patient characteristics of the 2 cohorts. Of the 14 FLT3/TKD+ cases analyzed by Whitman, 8 had 100% mutated FLT3 alleles, 6 had greater than 50% mutant level, indicating either biallelic disease due to uniparental disomy (UPD) or loss of WT allele in at least some cells in every case. In our original series of 127 FLT3/TKD mutants, only 3 cases had mutant levels indicative of definite biallelic disease (71%, 88%, and 93%).2 This is in accord with FLT3/TKD levels reported by others,3,4 and contrasts with FLT3/ITDs where we found mutant levels greater than 50% in 15% of cases.5 The latter are associated with a very poor prognosis.5-8 This may be an effect of UPD per se rather than increased mutant FLT3 dose, possibly through the biallelic presence of other genes; if so, a similar adverse impact might arise with some higher level FLT3/TKDs. Biallelic disease is readily detected by genome-wide SNP analysis,9 and of 35 ITD−TKD+ cases with higher FLT3/TKD mutant level subjected to SNP analysis, only one had chromosome 13 UPD detected, and this was probably due to consanguinity.10 Clearly, there is a need to explore the incidence and impact of biallelic FLT3/TKDs further. In the interim, we believe the suggestion by Whitman that normal karyotype patients with an FLT3/TKD “may benefit from more aggressive postinduction regimens” should be viewed with caution.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David C. Linch, Department of Haematology, Cancer Institute, University College London, 72 Huntley Street, London WC1E 6DD, United Kingdom; e-mail: d.linch@ucl.ac.uk.