Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients exhibit a variable clinical course. To investigate the association between clinicobiologic features and responsiveness of CLL cells to anti-IgM stimulation, we evaluated gene expression changes and modifications in cell-cycle distribution, proliferation, and apoptosis of IgVH mutated (M) and unmutated (UM) samples upon BCR cross-linking. Unsupervised analysis highlighted a different response profile to BCR stimulation between UM and M samples. Supervised analysis identified several genes modulated exclusively in the UM cases upon BCR cross-linking. Functional gene groups, including signal transduction, transcription, cell-cycle regulation, and cytoskeleton organization, were up-regulated upon stimulation in UM cases. Cell-cycle and proliferation analyses confirmed that IgM cross-linking induced a significant progression into the G1 phase and a moderate increase of proliferative activity exclusively in UM patients. Moreover, we observed only a small reduction in the percentage of subG0/1 cells, without changes in apoptosis, in UM cases; contrariwise, a significant increase of apoptotic levels was observed in stimulated cells from M cases. These results document that a differential genotypic and functional response to BCR ligation between IgVH M and UM cases is operational in CLL, indicating that response to antigenic stimulation plays a pivotal role in disease progression.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a disease characterized by an extremely heterogeneous clinical course; some patients may live for many years without requiring any treatment, whereas others, despite therapy, experience a rapid progression and in some cases an unfavorable fate.1,2

Several biologic parameters have allowed the risk stratification of CLL patients.3 One of the most reliable parameters is represented by the presence or absence of a significant level of somatic mutations within the immunoglobulin (Ig) variable heavy (VH) region genes. CLL patients with an unmutated IgVH status (UM-CLL) show a worse prognosis, whereas patients with mutated status show better prognosis.4,5 In line with this, gene expression analyses have shown a unique signature associated with mutated (M-CLL) and UM-CLL cells, and have highlighted an up-regulation of several genes linked to cell cycle and cell signaling in UM-CLL.6,7 Other biologic indicators of a poor clinical behavior are represented by genomic aberrations,8 surface expression of the CD38 antigen,4,9 and the intracytoplasmic presence of the ZAP-70 protein.10,11 CD3812 and the tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 have been shown to increase B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling in UM-CLL,13,14 and the coexpression of CD38 and ZAP-70 appears to correlate with a very strong activation of BCR signal transduction.15,16 These markers of progressive disease seem to strengthen the hypothesis that BCR signaling plays an important role in the proliferation and maintenance of the malignant B cells.

The reasons for disease initiation and progression have so far not been fully elucidated. It has been suggested that antigen stimulation, along with interactions with accessory cells and cytokines, may represent the promoting factor that stimulates proliferation of the neoplastic cells, thus protecting them from apoptosis. These effects may differ in distinct patients and could lead to the disparity of clinical behavior in this disease.17 Furthermore, there is evidence indicating that CLL may be sustained by an antigen-driven process based on a restriction of the repertoire, as well as by shared antigen-binding motifs used by neoplastic B cells.17 In vitro cross-linking of BCR molecules with antibodies to IgM mimics the engagement of antigens with BCR and transmits signals to the cell nucleus.

In view of the different clinical and biologic behavior of M-CLL and UM-CLL IgVH genes, in the present study we investigated the gene expression profile changes, as well as the functional modifications in the proliferation and apoptotic rate, and cell-cycle induction upon BCR ligation with immobilized IgM in these 2 distinct subgroups of CLL.

Methods

Patients

Twenty CLL patients, 10 females and 10 males, with a median age of 51.5 years (range, 30-84 years) were evaluated at the time of presentation before any treatment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Sapienza” University of Rome. Informed consent to the blood collection and to the biologic analyses included in the present study was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The diagnosis of CLL was based on the presence in the peripheral blood of more than 5 × 109/L lymphocytes that expressed a conventional CLL morphology and immunophenotype (CD5/CD20+, CD23+, weak CD22+, weak sIg+, CD10−). According to Binet staging system, 10 patients were in stage A and 10 in stage B. Patients' characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Routine analyses included the IgVH gene mutational status,18 ZAP-7010,11 and CD38 evaluation by flow cytometry,9 fluorescence in situ hybridiza-tion (FISH) analysis for the identification of cytogenetic aberrations involving 11q22-23, 13q14, 6q21, and 17p13 regions and trisomy 12, and p53 sequencing.18

CLL cell separation and stimulation

Blood samples were collected from CLL patients. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway). Freshly isolated PBMCs were subsequently enriched in CD19+ B cells (> 98%) by standard positive selection using a specific anti-CD19 antibody conjugated with magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). Purified B cells were cultured in 96-well U-bottom plates (Corning, New York, NY) coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μg/mL anti–goat F(ab′)2 IgG developed in rabbit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). B lymphocytes were plated at 5 × 105 cells/well in RPMI 1640 medium (Cambrex BioScience, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; HyClone, South Logan, UT), 0.3 mg/mL l-glutamine, and 1% Pen-strepto (Euro-Clone, Pavia, Italy). BCR stimulation was performed by adding a goat F(ab′)2 anti–human IgM (μ-chain specific; Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL for 24 hours; in some selected experiments, stimulation was carried out for 6 hours and/or 48 hours.

RNA extraction and oligonucleotide microarray

After 24 hours of incubation, unstimulated (US-CLL) and stimulated (S-CLL) cells were lysed and total RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. In selected experiments, RNA was extracted also after 6 and 48 hours of stimulation.

To assess RNA quality, 2 μL RNA from each sample was analyzed by electrophoresis on agarose gel; for all samples the 260:280 ratio was more than 1.8, as required for microarray analysis.

HGU133 Plus 2.0 gene chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were used to determine gene expression profiles. The detailed protocol for sample preparation and microarray processing is available from Affymetrix.19

Statistical methods for microarray analysis

Oligonucleotide microarray analysis was performed with dChip software (http://www.dchip.org, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA), which uses an invariant set normalization method. The array with median overall intensity was chosen as the baseline for normalization. Model-based expressions were computed for each array and probe set using the PM-MM model.20

Nonspecific filtering criteria for unsupervised clustering required the expression level to be higher than 100 in more than 30% of the samples and the ratio of the standard deviation (SD) to the mean expression across all samples to be between 0.5 and 1000. Hierarchic clustering was used as described by Eisen et al.21

To specifically identify genes differentially expressed between US-CLL and S-CLL samples in different subgroups of CLL, a t test was applied. Probe sets were required to have an average expression of 100 or more in at least one group, a fold change of 1.5 or more, and a P value of .05 or less. Furthermore, to strengthen the robustness of these results, the false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated over 5000 permutations. All experimental and microarray data can be found at Ematologia La Sapienza.22

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA (1 μg) was retrotranscribed using the Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Real-time quantitative–polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) analysis was performed using an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system and the SYBR green dye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) method, as previously described.23 Real-time PCR conditions were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, 95°C for 15 seconds, and 60°C for 1 minute; for 40 cycles. For each sample, CT values for GAPDH were determined for normalization purposes, and delta CT (ΔCT) between GAPDH and target genes was calculated. Primers were designed using the Primer Express 1.0 software (PE Biosystems). The following primers were used: 5′ GAPDH, 5′-CCACCCATGGCAAATTCC-3′; 3′ GAPDH, 5′-GATGGGATTTCCATTGATGACA-3′; 5′ SYK, 5′-ATGGAAAAATCTCTCGGGAAGAA-3′; 3′ SYK, 5′-TGGCTCGGATCAGGAACTTT-3′; 5′ ZAP-70, 5′-GCACCCGAATGCATCAAC-3′; and 3′ ZAP-70, 5′-GACAAGGCCTCCCACATG-3′.

Cell-cycle analysis

Cell-cycle distribution changes were evaluated using the acridine orange (AO) technique, as previously described.24 The percentage of cells in G0, G1, S, and G2M and the mean RNA content of G0/1 cells were determined by measuring simultaneously the DNA and RNA total cellular content. RNA content of G0/1 cells was expressed as RNA-index (RNA-I G0/1), determined as the ratio of the mean RNA content of G0/1 cells of the samples multiplied by 10 and divided by the median RNA content of control lymphocytes. G0 cells were defined as cells with an RNA content equal to or lower than that of control normal peripheral blood lymphocytes.

Flow cytometric analyses were carried out using a FACSCan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) operated at 488 nm, which detects green (F530-DNA) and red (F>620-RNA) fluorescence. Data acquisition and analysis (10 000-20 000 events) were performed with the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Cell-cycle distribution was analyzed using the ModFit LT software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

In vitro proliferation assay

For each patient, 5 × 105 CD19+ B cells in 200 μL/well in 96-well microtiter plates were seeded in triplicate and cultured for 24 and 48 hours in the presence or absence of anti-IgM. After the indicated time of culture, cells were incubated with 0.037 MBq [3H]thymidine/well (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) for 18 hours, harvested, and counted using a beta-counter (Packard Bioscience, Groningen, The Netherlands). Results are expressed as the ratio of the mean counts per minute (cpm) of S-CLL versus US-CLL.

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was measured by 2 different methods: after 24 hours, cultured cells were double stained with FITC-conjugated annexin-V/propidium iodide (Immunotech Research, Vaudreuil-Dorion, QC). After staining, apoptotic cells were evaluated by flow cytometry and the data analyzed using the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Furthermore, apoptosis was measured after 24 to 48 hours of culture upon stimulus by evaluating the sub-G0/1 peak on DNA-frequency histograms using the AO technique described in “Cell-cycle analysis,” which measures apoptotic cells based on the decreased stain ability of apoptotic elements in DNA green fluorescence (sub-G0/1 peak on DNA frequency histograms) coupled with a higher RNA red fluorescence (which is common to chromatin condensation),24,25 cell debris being excluded from the analysis on the basis of their forward light scatter properties.

Statistical analysis for proliferation studies and apoptosis

The 2-sided Student t test was used to evaluate the significance of differences between groups. Results are expressed as the means plus or minus SD.

Results

Microarray analysis reveals a different responsiveness profile between IgVH UM and M CLL cases upon BCR cross-linking

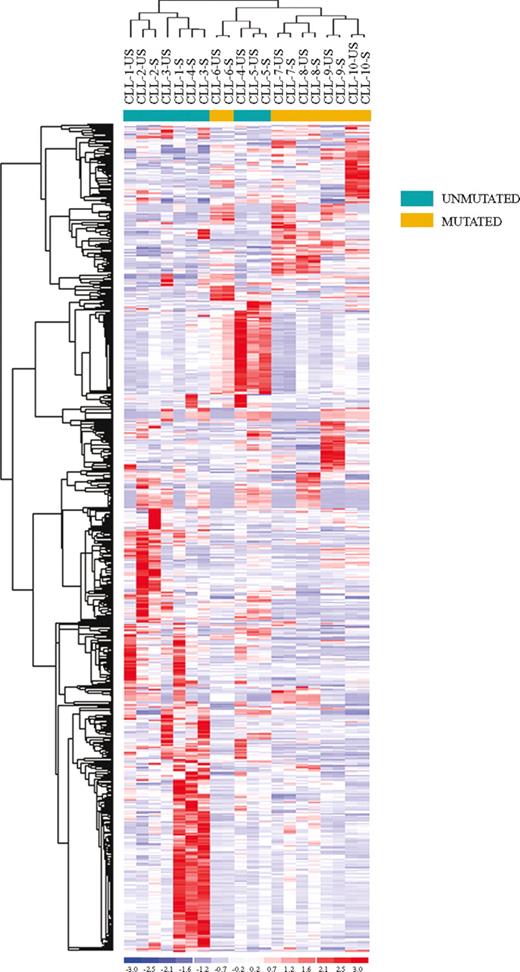

To evaluate the effects of BCR stimulation on CLL cells, we performed gene expression profile studies on CD19+ purified US-CLL and S-CLL cells isolated from 10 CLL patients (CLL-1-10) with different clinical and biologic features and stimulated the cells for 24 hours (Table 1). Our first analysis used an unsupervised approach: applying nonspecific filtering criteria to all samples, 673 probe sets, corresponding to 635 genes, were selected. As shown in Figure 1, unsupervised hierarchic clustering based on the expression of this set of genes identified 2 major clusters: the first included exclusively CLL patients with an UM configuration of the IgVH genes, whereas the second cluster included all the IgVH M cases and a single UM patient (CLL-5).

Unsupervised clustering of unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) CLL samples. Unsupervised clustering of the unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) CLL samples evaluated by gene expression profiling upon BCR cross-linking. Relative levels of gene expression are depicted with a color scale: red indicates highest levels of expression; blue, lowest levels of expression.

Unsupervised clustering of unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) CLL samples. Unsupervised clustering of the unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) CLL samples evaluated by gene expression profiling upon BCR cross-linking. Relative levels of gene expression are depicted with a color scale: red indicates highest levels of expression; blue, lowest levels of expression.

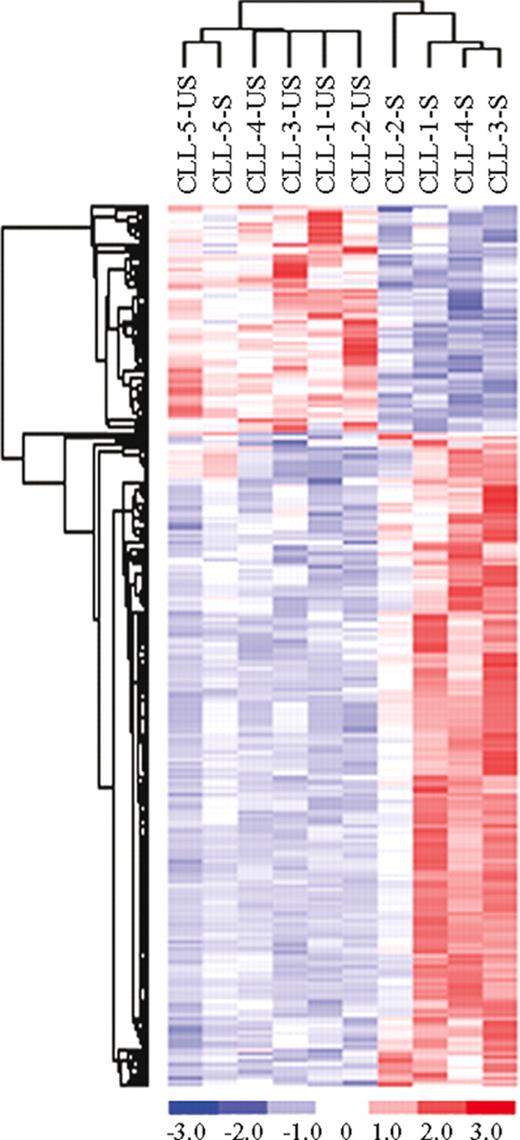

Second, to identify genes that were modulated upon BCR stimulation, we performed a t test between US-CLL and S-CLL samples. This analysis selected 71 differentially expressed genes: it is important to underline that this approach unequivocally showed that BCR stimulation induces relevant changes mostly within IgVH UM patients (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). We thus performed a supervised analysis to compare US-CLL and S-CLL samples within IgVH UM and M cases. In the IgVH UM cases, the t test identified 197 genes differentially expressed upon BCR cross-linking, the majority being highly expressed in the stimulated cells (Figure 2). A large set of these genes, reported in Table 2, codify for proteins involved in BCR signaling and/or in BCR activation; in particular, among the more represented functional groups, we found several genes involved in signal transduction (TNFAIP3, DUSP2, DUSP4, DUSP10, NPM1, SYK, CXCR4, CCL3, CCL4, HOMER1), regulation of transcription (EGR1, EGR2, EGR3, NME1, NME2, ZNF238, TOP1MT), and metabolism (LDHB, HSP90AB1, PSMCs, ATP2A3). Moreover, different expression levels were identified also in a set of genes involved in cell- cycle regulation (CCND2, CDK4, PTPN6, CHES1) and cytoskeleton organization (ACTB, ACTG1, K-ALPHA1, TUBB, BICD2). Notably, after 6 hours of stimulation, we already observed an increase of a set of these genes (EGR3, NR4A1, DUSP4, LRMP, CD39, and an unknown sequence), suggesting that gene expression changes start to occur relatively early and increase over time (Figure S2). Contrariwise, when the same approach was applied to US-CLL and S-CLL cells within IgVH M cases, no genes were selected in this analysis.

Comparison between unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) samples in CLL unmutated (UM) patients. Identification of 197 genes differentially expressed between unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) samples in CLL unmutated (UM) patients.

Comparison between unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) samples in CLL unmutated (UM) patients. Identification of 197 genes differentially expressed between unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) samples in CLL unmutated (UM) patients.

Overall, these results highlight that, whereas CLL cells from IgVH UM patients are responsive to BCR cross-linking, this is not the case for CLL cells from IgVH M patients, as these cells appear to be anergic to such stimulus.

Response to BCR stimulation is correlated to IgM expression

As previously mentioned, through a supervised approach it was possible to identify a set of genes modulated after BCR stimulation. Unsupervised clustering suggested that 3 samples (CLL-5, CLL-7, and CLL-8) showed an anomalous behavior, with 2 IgVH M-CLL cases displaying gene modulation upon BCR stimulation and 1 IgVH UM-CLL patient with very few changes occurring after stimulation, indicating that other factors may influence signaling through BCR. To explain this phenomenon, different clinicobiologic features were investigated, namely CD38 and ZAP-70 expression, as well as cytogenetic aberrations. The only parameter that was highly related to the response to BCR cross-linking was represented by the IgM levels (evaluated by microarray analysis). In fact, although IgM could be detected in all CLLs analyzed at both the RNA (Figure S3) and protein (data not shown) level, CLL cases that did not respond to BCR ligation showed lower IgM expression levels. Furthermore, IgM mRNA expression levels were not affected by BCR ligation.

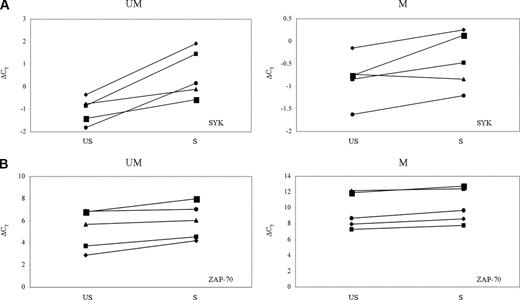

Evaluation of SYK and ZAP-70 expression by Q-PCR analysis

Among the different tyrosine kinases involved in BCR activation, SYK represents an early signaling intermediate of this cascade in B cells.26 ZAP-70, a tyrosine kinase of the Syk family, plays a role in increasing BCR signaling after cross-linking of IgM in CLL.13 To investigate the relative expression changes of these kinases upon BCR engagement, SYK and ZAP-70 expression levels in US-CLL and S-CLL cells were evaluated, after 24 hours of IgM stimulation, by Q-PCR. This analysis was performed on 10 CLL samples (5 IgVH UM: CLL-1-5; 5 IgVH M cases: CLL-6-9 and CLL-12). Q-PCR results are reported in Figure 3: SYK expression levels decreased in S-CLL samples compared with US-CLL samples. Moreover, the down-modulation of this gene was statistically significant (P = .009) exclusively in the CLL IgVH UM cases. Contrariwise, no significant differences in ZAP-70 expression levels were observed after stimulation in both IgVH UM and M CLL cells. Overall, these findings indicate that, upon BCR engagement, SYK, but not ZAP-70, is differentially modulated between IgVH UM and M CLL cases. Hence, these data further corroborate the microarray results that show a downmodulation of SYK and no changes in ZAP-70 expression levels.

SYK and ZAP-70 changes upon stimulus. SYK (A) and ZAP-70 (B) expression upon 24 hours of BCR stimulation between unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) samples in CLL unmutated (UM) and mutated (M) cases. Gene expression values are expressed by ΔCT values: low ΔCT values correspond to high gene expression levels.

SYK and ZAP-70 changes upon stimulus. SYK (A) and ZAP-70 (B) expression upon 24 hours of BCR stimulation between unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) samples in CLL unmutated (UM) and mutated (M) cases. Gene expression values are expressed by ΔCT values: low ΔCT values correspond to high gene expression levels.

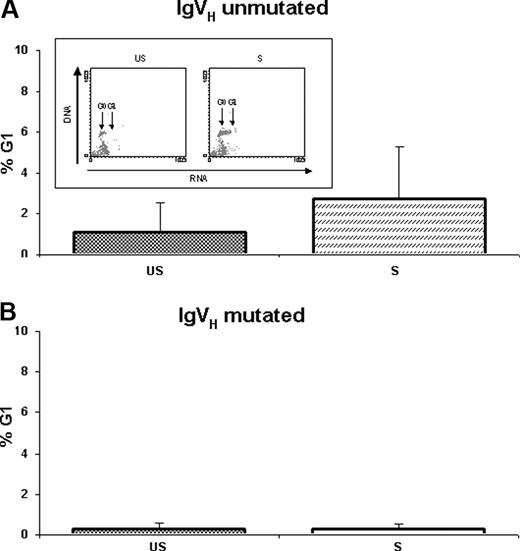

IgM cross-linking acts by inducing cell-cycle progression of primary CLL cells from IgVH UM patients

To evaluate the effects of IgM cross-linking on cell-cycle distribution changes, cell-cycle analysis was performed on US-CLL and S-CLL cells after 24 and 48 hours upon stimulus. As shown in Figure 4A, IgM cross-linking induced a considerable proliferative activity on primary CLL cells from IgVH UM patients (7 cases: CLL-1, CLL-2, CLL-11, CLL-13, CLL-18, CLL-19, and CLL-20), as shown by a statistically significant increase of cells in the G1 phase from 1.06% ± 1.50% in US-CLL cells to 2.74% ± 2.50% in S-CLL cells (P = .037) after 48 hours of exposure to anti-IgM. Conversely, resistance to anti-IgM–mediated cell-cycle progression was observed in CLL cells from IgVH M patients (5 cases: CLL-9, CLL-12, CLL-14, CLL-15, and CLL-17): from 0.28% ± 0.31% in US-CLL cells to 0.28% ± 0.26% in S-CLL cells (Figure 4B).

G1 phase changes from unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) B-CLL cells. G1 phase changes (mean percentages ± SD) from unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) B-CLL cells were evaluated using the AO technique after 48 hours of culture in (A) IgVH unmutated and (B) IgVH mutated samples. Representative experiment obtained from an IgVH unmutated patient is shown in the box.

G1 phase changes from unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) B-CLL cells. G1 phase changes (mean percentages ± SD) from unstimulated (US) and stimulated (S) B-CLL cells were evaluated using the AO technique after 48 hours of culture in (A) IgVH unmutated and (B) IgVH mutated samples. Representative experiment obtained from an IgVH unmutated patient is shown in the box.

Induction of proliferation after IgM cross-linking

To corroborate the fact that by gene expression profiling a set of cell cycle–related genes is up-regulated in IgVH UM cases, the effects on proliferation upon IgM cross-linking were measured by thymidine uptake. Primary cells from 7 IgVH UM cases (CLL-1, CLL-2, CLL-11, CLL-13, CLL-18, CLL-19, and CLL-20) displayed a proliferative response after 24 and 48 hours of stimulation, with an increase of 2.7- and 1.9-fold change, respectively. At variance, no difference in thymidine uptake was observed in S-CLL and US-CLL cells from 4 IgVH M patients (CLL-9, CLL-12, CLL-14, and CLL-15).

IgM cross-linking effects on apoptosis modulation

To explore if the proliferative effects of IgM cross-linking could be associated with a cytoprotective activity, apoptosis levels were also analyzed at 24 and 48 hours in IgVH UM and M CLL cells using the annexin-V and AO techniques. In 5 IgVH UM cases (CLL-1, CLL-2, CLL-4, CLL-5, and CLL-8), IgM cross-linking induced a decrease in apoptosis. In fact, at 24 hours upon BCR engagement, the level of apoptosis in S-CLL cells was 55.4% plus or minus 20.8%, whereas the value observed in US-CLL samples was 68.7% plus or minus 15.0%. At variance, 4 IgVH M cases (CLL-6, CLL-7, CLL-10, and CLL-16) became sensitive to IgM-triggered apoptosis at 24 hours, with a mean percentage of annexin-V–binding cells of 50.3% plus or minus 17.9% as opposed to the basal rate of spontaneous apoptosis of 17.7% plus or minus 9.3%. These findings were also confirmed when apoptosis levels were evaluated using the AO technique. In fact, within the 7 IgVH UM cases (CLL-1, CLL-2, CLL-11, CLL-13, CLL-18, CLL-19, and CLL-20) IgM cross-linking induced a decrease in the percentage of subG0/1 cells in 4 of 7 patients (from 41.12% ± 16.9% in US-CLL cells to 33.71% ± 11.7% in S-CLL cells; P = .06; data not shown). Contrariwise, a significant increase of apoptosis, from 33.42% plus or minus 21.1% in US-CLL cells to 44.72% plus or minus 27.3% in S-CLL cells (P = .04), was observed at 48 hours in 4 of 5 CLL cells from IgVH M patients (CLL-9, CLL-12, CLL-14, and CLL-15). A cytoprotective effect of IgM cross-linking was observed in the last IgVH M sample (CLL-17: from 35.5% in US-CLL cells to 23.2% in S-CLL cells).

Discussion

The heterogeneous clinical course of CLL represents a fascinating biologic problem, quite unique to this disease within the spectrum of hematologic malignancies. Many speculations have been put forward in an attempt to explain disease progression versus disease stability. In the present study, we sought to explore the possibility, frequently hypothesized,17,27 that antigen stimulation, or response to antigenic stimulation, may play a pivotal role in the expansion of the leukemic clone.

Gene profiling has proven very useful in clarifying different important aspects of CLL pathogenesis and prognosis. By using this technique it has, in fact, been shown that CLL is a unique disease,6,7 that ZAP-70 represents an important prognostic marker,6,10,11 and that a gene signature is associated with CD38 expression28 and with disease progression29 ; from a functional point of view, it has also been shown that CLL cells from IgVH unmutated cases display a profile that resembles that of activated B cells.7 Therefore, we first used this technique to identify molecular events that may play a role in the progression of the disease and subsequently confirmed the results obtained by performing functional in vitro experiments. We used an experimental model, based on the stimulation of the BCR of CLL cells with an IgM immobilized antibody, that can mimic the in vivo conditions of progression physiopathology.30 Remarkably, our study shows that although IgM stimulus induces significant gene expression changes in the UM-CLL subgroup, no changes are observed in the M-CLL subgroup. The strongest gene expression changes occurred, as expected, in genes involved in signal transduction—in particular, in several DUSP members, namely DUSP2, DUSP4, and DUSP10, which are important regulators of the MAPK pathway,31 as well as CCL3 and CCL4, important regulators of calcium homeostasis and motility.32,33 Similarly, we observed a consistent up-regulation of several members of the EGR family (EGR1, EGR2, and EGR3), NR4A family (NR4A1, NR4A2, and NR4A3), and NME1 and NME2, involved in transcription regulation,34-37 pinpointing that these processes are strongly affected by IgM stimulation.

In line with previously published data,6 gene expression profiling also detected an upmodulation of genes involved in cell-cycle regulation coupled with cell-cycle progression. In fact, although for many years CLL has been considered a malignancy of mature lymphocytes with an extended survival but a low proliferative potential, it has been recently documented in vivo, using a nonradioactive method to measure CLL cell kinetics, that CLL cells are nonquiescent,38 indicating that CLL is an overall dynamic disease.

It has also been demonstrated that immunostimulatory DNA oligonucleotides induce cell-cycle progression, proliferation, and enhanced survival in patients with progressive disease and a UM IgVH profile.39 On the contrary, the same stimulation induced a cell-cycle arrest and leukemic cell apoptosis in the majority of cases with stable disease and M IgVH. Furthermore, Longo et al40 performed an analysis of cell-cycle regulatory protein expression after stimulation and showed that cyclin D3, which plays a role in the G1 phase, increased in all stimulated CLL cells; contrariwise, cyclin A, which is expressed in the S phase of the cell cycle, is induced only in CLL cells that proliferate after stimulation; the AKT and ERK kinases appear to play a key role in these events.39,40

In line with these recent findings, our results indicate that IgM stimulation induces the modulation of several genes involved in signal pathways controlling survival and proliferation in UM-CLL. In particular, we observed (1) the increased expression of NFATC1 that participates in the ERK and JNK MAPK pathways41 ; (2) the downmodulation of CDC25B involved in the p38 MAPK pathway42 ; and (3) the upmodulation of a set of genes involved in cell proliferation,43 the most important being CCND2 and CDK4. These results are also in agreement with Muzio et al44 who recently reported that a subset of CLL patients display an activation of ERK1/2 and an increased transactivation of NF-AT, upon Ig ligation.

Cell-cycle analysis upon IgM stimulation confirmed the progression of cell cycle exclusively in UM-CLL cells; as a matter of fact, in agreement with Deglesne et al,30 it was possible to highlight an increase in the percentage of cells in the G1 phase, although the rate of cells in the S phase was, at this time point, unmodified. These results were further corroborated by the proliferation assay that showed a proliferative response only in UM-CLL cases upon BCR cross-linking.

It has been shown that the response to IgM stimulus is proportional to the levels of IgM exposed on the cell surface.45 Accordingly, we could document that the transcriptional levels of IgM are higher in UM-CLL cells and appear to be the parameter that better correlates with responsiveness to BCR stimulation. This finding supports the hypothesis that the IgM levels play a more important role than CD38 and ZAP-70 expression in the stimulus response. In our study, the CD38 antigen was expressed on the surface of the leukemic cells only in 3 patients; although the number of CD38+ patients is small, we propose that CD38 expression may contribute primarily to the secondary events that follow stimulation. Similarly, in the past it was thought that ZAP-70 could play a major role in BCR signal transduction. It has now been unequivocally demonstrated that BCR signaling predominantly uses the tyrosine kinase SYK and that ZAP-70 contributes only to enhance the reaction and to prolong the persistence of the stimulus.46 Consistent with these findings, in our study the levels of ZAP-70 expression did not change upon stimulation in UM-CLL and M-CLL cells. Contrariwise, a significant difference in SYK expression levels was observed at 24 hours upon stimulus exclusively in UM-CLL cells, confirming published data47 on the predominant role of the SYK molecule in the process of BCR signal transduction. Finally, we found un up-regulation of SHP-1 (alias PTPN6),48 a gene that interacts with ZAP-70.

The role of apoptosis in CLL progression is still debated and contradictory data have been obtained on IgM S-CLL and US-CLL cells. In the past, an enhanced apoptosis in CLL cells before and after IgM stimulus, partly dependent on CD38 expression, has been reported.49,50 More recently, our group has demonstrated that leukemic cells taken from patients with stable disease are more susceptible to enter apoptosis than leukemic cells obtained from progressive patients24 ; other authors have shown that CLL cells show defects in apoptosis induction and have correlated this phenomenon with the high activity of Lyn, a tyrosine kinase involved in signal transduction, that is constitutively phosphorylated in leukemic cells.51

Gene expression analysis showed that, upon stimulation, a very small set of genes involved in the apoptotic pathway is up-regulated only in UM-CLL cells, suggesting that apoptosis may represent a minor phenomenon upon IgM ligation. Interestingly, the genes hereby identified exert an antiapoptotic function. In fact, the increase of genes correlated to the TNF and NFKB signaling pathways, namely CD40, a member of the TNF receptor, TRAF, a TNF receptor-associated factor, and TNFAIP3, a gene involved in the negative regulation of NFKB pathway, suggests that these genes interact in mediating apoptosis inhibition.52-54 To confirm these results, we analyzed the apoptotic rate of CLL cells after IgM stimulation; whereas in M-CLL cases the number of apoptotic cells significantly increased after 48 hours upon ligation, in UM-CLL cells at 24 and 48 hours after IgM stimulation there was a trend toward a reduction in the apoptotic rate. These results indicate that IgM stimulation contributes to the survival of UM-CLL cells, whereas in M-CLL cases no antiapoptotic signal is induced and therefore cells die by speeding up their apoptotic program.

Our results differ from those reported in a recent paper,55 where the authors evaluated the gene expression profile of B cells from healthy donors and CLL patients at several, but short, time points after IgM stimulation. Their data indicate that an increased apoptosis can be observed in CLL cells compared with normal B cells; furthermore, the authors showed, rather unexpectedly, an up-regulation of proapoptotic genes in samples from patients with aggressive disease. Among the reasons that may contribute to the divergent results, it must be noted that the patients' clinicobiologic features differ profoundly between the 2 studies. More importantly, in our experiments, more prolonged IgM stimulation time points have been evaluated, and these experimental conditions, presumably, allowed the documentation of a positive correlation between the leukemic cell behavior and the neoplastic expansion; it must be underlined that at 6 hours upon stimulus, we already observed an increase in the expression levels of a small set of genes, and these levels were then reconfirmed at 24 hours. Finally, 2 technical issues may have contributed to the different results obtained: first, in our experimental model an immobilized IgM was used, whereas Vallat et al55 used a soluble IgM; second, from a statistical point of view, the presence of a third group of samples (ie, normal B lymphocytes) may have interfered with data normalization and, therefore, with gene expression profiling data analysis.

Overall, our data support the hypothesis that the stimulation of a self- or non–self-antigen is a contributing factor toward maintaining the disease.

In conclusion, the results of this study challenge the belief that CLL is a disease characterized by a defective apoptosis and accumulation of malignant cells. Indeed, we show that, unlike in M-CLL cases, UM-CLL cells respond to signals delivered by surface IgM by up-regulating several genes associated with cell cycle and allowing cell growth and expansion, thus ultimately contributing to the unfavorable clinical course of CLL patients with an UM IgVH profile.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC; Milan, Italy), Ministero dell'Istruzione, Università e Ricerca (MIUR, Rome, Italy), Programi di Ricera di Interesse Nazionale (PRIN; Rome, Italy), Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricera di Base (FIRB; Rome, Italy), and Fondazione Internazionale di Ricerca in Medicina Sperimentale (FIRMS, Torino, Italy).

Authorship

Contribution: A.G. designed research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; S.T. and S.C. performed gene expression profile and molecular experiments, and contributed to the preparation of the paper; R.M., N.P., S.S., M.M., M.S.D.P., M.R.R., and M.M. performed functional cell experiments; F.C. analyzed the data and contributed to the preparation of the paper; F.R.M. and I.D.G. analyzed patients; R.F. reviewed the design of the study, analyzed and discussed the results, and critically revised the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robin Foà, Division of Hematology, Via Benevento 6, 00161 Rome, Italy; e-mail: rfoa@bce.uniroma1.it.