Abstract

Early life exposure to noninherited maternal antigens (NIMAs) may occur via transplacental transfer and/or breast milk. There are indications that early life exposure to NIMAs may lead to lifelong tolerance. However, there is mounting evidence that exposure to NIMAs may also lead to immunologic priming. Understanding how these different responses arise could be critical in transplantation with donor cells expressing NIMAs. We recently reported that murine neonates that received a transplant of low doses of NIMA-like alloantigens develop vigorous memory cytotoxic responses, as assessed by in vitro assays. Here, we demonstrate that robust allospecific cytotoxicity is also manifest in vivo. Importantly, at low doses, NIMA-expressing cells induced the development of in vivo cytotoxicity during the neonatal period. NIMA-exposed neonates also developed vigorous primary and memory allospecific Th1/Th2 responses that exceeded the responses of adults. Overall, we conclude that exposure to low doses of NIMA-like alloantigens induces robust in vivo cytotoxic and Th1/Th2 responses in neonates. These findings suggest that early exposure to low levels of NIMA may lead to long-term immunologic priming of all arms of T-cell adaptive immunity, rather than tolerance.

Introduction

Exposure to alloantigens is commonly considered to be limited to clinical transplantation settings. However, there is natural exposure to alloantigens that occurs in early life. Maternal cells can be transferred across the placenta during gestation,1-9 thereby exposing the fetus to maternal antigens. Maternal cells and antigens are also present in breast milk, which serves as an additional potential source of exposure during neonatal life.2,10-12 Human mothers are antigenically foreign to their fetuses because maternal cells express a large number of both major and minor histocompatability antigens that are not passed down to the fetus; these are called noninherited maternal antigens (NIMAs). Thus, this transfer of NIMA-expressing maternal cells is tantamount to a natural transplantation of allogeneic cells.

Murine fetuses and neonates develop long-term tolerance when exposed experimentally to high doses of semiallogeneic cells,13-21 which has led to the hypothesis that developing animals are particularly susceptible to tolerance induction to alloantigens. Therefore, it might be predicted that in utero and neonatal exposure to NIMA leads to specific tolerance after birth. Indeed, there are several studies that support this hypothesis. First, a retrospective study of human kidney transplant patients demonstrated that renal grafts expressing NIMAs had better long-term acceptance than those that did not, consistent with tolerance to NIMAs.22 Furthermore, 2 murine NIMA studies23,24 showed that mice exposed to NIMAs during early life accepted NIMA-expressing heart allografts. However, these same studies contain evidence supporting the idea that neonatal and even fetal animals can also mount productive immune responses and become primed to NIMAs. First, Burlingham et al22 found that episodes of acute rejection of renal grafts occurred with greater frequency and at earlier time points with NIMA-expressing grafts compared with those that did not express NIMAs. This suggests that some individuals may have become primed—not tolerized—to NIMAs. Second, in the murine cardiac transplant models,23,24 tolerance to NIMA-expressing heart grafts was observed in only 40% to 60% of the mice. In addition, acute rejection episodes similar to those seen in the human study were observed.25 Thus, exposure to maternal cells or antigens during early life may lead to outcomes other than tolerance. In some instances, this exposure may result in priming against NIMAs, and the subsequent rejection of NIMA-expressing grafts in adult life.

The mechanisms underlying the development of tolerance versus priming to NIMA alloantigens are not well understood. However, there is emerging evidence that the level of NIMA exposure may be key in determining the resulting immunologic response. For example, tolerance to NIMA-expressing heart grafts failed to develop in mice unless they were exposed to NIMAs both in utero and through breast milk (ie, to a relatively high dose of NIMAs).23 Conversely, we have shown26 that transplantation of 1-day-old or younger murine neonates with low doses of either semiallogeneic or fully allogeneic adult cells leads to priming for in vitro cytotoxicity. However, the development of in vivo T-cell responses, which are important in NIMA transplantation settings, was not examined. Therefore, in this report we have extended our studies to examine whether in vivo cytotoxic and Th responses develop in neonates exposed to NIMA-like alloantigens. The findings demonstrate that exposure to low doses of alloantigen in the neonatal period induces phenotypic changes on antigen-presenting cell (APC) populations that are consistent with functional maturation. In association with the phenotypic changes, vigorous in vivo cytotoxic responses to NIMA-like alloantigens developed during the neonatal period. Although donor cells were no longer detectable by 9 days after injection, allospecific in vivo cytotoxic responses persisted into adulthood. In addition to cytotoxic function, vigorous antidonor Th1/Th2 primary and memory responses developed in the neonate, at levels significantly higher than adult responses. Therefore, transient exposure to low levels of NIMA-like alloantigens in early life can lead to long-term priming for both cytotoxic and Th functions. Finally, IFNγ secretion, but not CD40L expression, by donor cells was found to be partly responsible for the development of neonatal cytotoxic responses. These findings provide important insights into the functional outcomes of neonatal exposure to NIMAs, and indicate that priming of all arms of T-cell immunity can occur upon exposure of neonates to NIMA-like alloantigens.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, CD40L−/− (B6.129S2-Cd40lgtm1Imx/J), IFNγ−/− (B6.129S7-Ifngtm1Ts/J), GFP+ (C57BL/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/J) (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), BALB/c (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), and FVB (M. Nussenzweig, Rockefeller University, New York, NY) mice were bred and housed under barrier conditions at the Division of Veterinary Resources of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. The colonies were free of commonly occurring infectious agents. BALB/c females from timed matings were monitored from days 19 to 21 of gestation; the day of birth was called day 0 of life. All animal procedures used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Preparation and injection of donor cells

Red blood cell (RBC)–depleted spleen cell suspensions from 2 or more adult (6-12 weeks old) C57BL/6, CD40L−/−, IFNγ−/−, GFP+, or (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 mice were prepared as described earlier.26 C57BL/6 peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) were obtained as described previously.27 C57BL/6 BM cells were harvested from the tibia and femur, and Lin− cells were purified (> 86%) using the Miltenyi Biotech (Auburn, CA) Lineage Cell Depletion Kit. BALB/c or (BALB/c × FVB) F1 neonates (≤ 1 day old) were injected via the facial vein with 2 × 105 (50 μL) donor cells. Six- to 10-week-old adult BALB/c mice were injected intravenously with 4 × 106 donor cells (100 μL); cell dose was adjusted to reflect the roughly 20-fold difference in total body weights between neonates and adults.

Flow cytometry

Phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated H-2Kd (SF1-1.1) and CD11c (HL3), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated H-2Kd (SF1-1.1), biotinylated I-A/I-E (2G9), and streptavidin-peridinin chlorophyll-a protein (PerCP) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). F4/80-FITC (CI:A3-1) and B220-FITC (RA3-6B2) were from Caltag (Carlsbad, CA). TER-119-FITC (TER-119) was from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). Samples were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson LSR I using CellQuest software (San Jose, CA).

CFSE and Far Red labeling of spleen cells

RBC-depleted spleen cells were resuspended in prewarmed (37°C) Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (107 cells/mL). Host-type cells were labeled with 0.5 μM carboxy-fluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE: Vybrant CFDA SE Cell Tracer Kit; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA), and donor-type C57BL/6 cells were labeled with 5 μM CFSE. For the IFNγ−/− and F1→F1 primary in vivo cytotoxicity assays, the indicated host and donor cell types were labeled with 0.5 μM and 5 μM Far Red, respectively (CellTrace Far Red DDAO-SE; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes). The cells were incubated with CFSE or Far Red for 10 minutes at 37°C, then diluted with fetal bovine serum (FBS; 10% final). Labeled cells were washed with cold HBSS, then mixed at a 1:1 ratio, for use in both the primary and memory in vivo cytotoxicity assays.

In vivo cytotoxicity assays

To examine primary responses, BALB/c neonates were injected with wild-type C57BL/6, CD40L−/−, or IFNγ−/− adult spleen cells, or C57BL/6 PBLs. For the assay of F1 cells into F1 mice, (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 spleen cells were injected into (BALB/c × FVB) F1 neonates. Uninjected neonates were maintained as controls. Labeled host- and donor-type spleen cells (5 × 107 − 1 × 108 cells in 50 μL) were injected intraperitoneally 7 days later. After 12 to 18 hours, spleen and lymph node cells were harvested, and the percentage of labeled allogeneic donor-type cells and syngeneic host-type cells was determined in individual neonates by flow cytometry. To control for natural killer (NK) cell–mediated killing of labeled allogeneic cells, the relative survival of donor-type cells in injected neonates was compared with survival in uninjected naive controls, using the following calculation to determine the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity: [1 − (% donor-type cells in experimental neonates/% host-type cells in experimental neonates)/(% donor-type cells in control neonates/% host-type cells in control neonates)] × 100.28,29 Memory cytotoxic responses of animals injected as neonates or adults were similarly assayed 5 to 15 weeks after injection of donor cells.

Preparation of cells for cytokine responses

For primary responses, neonatal and adult spleens were harvested 7 days after injection with C57BL/6 spleen cells. For memory responses, all animals were boosted 4 to 8 weeks after initial injection with an intravenous injection of the adult dose of C57BL/6 cells, and spleens from each group were harvested 3 days later. CD4+ spleen cells were positively selected (MS+ columns) using the Miltenyi Biotech magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) system, according to the manufacturer's directions. Preparations typically consisted of more than 90% CD4+ cells. Donor allogeneic splenic APCs were prepared from naive 6- to 12-week-old C57BL/6, as previously described.30 The cells were then washed twice and resuspended in culture media for use in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT).

Culture conditions for cytokine ELISA and ELISPOT

Purified host CD4+ spleen cells (2 × 105) were plated in 200 μL culture media and stimulated with 4 × 105 donor allogeneic APCs. Culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640 containing 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 5 × 10−2 mM 2-ME (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and 10% heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 minutes) FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were harvested, replated in ELISPOT wells, and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for an additional 24 hours before developing, as previously described in detail.31 Supernatants from parallel cultures were harvested at 48 or 72 hours, and IFNγ and IL-4 content were assessed using mouse-specific cytokine ELISA kits (Pierce, Rockford IL), according to the manufacturer's directions.

GFP-specific real-time PCR to detect donor cells

BALB/c neonates and adults were injected with GFP+ adult spleen cells. Two to 9 days later, spleens from individual mice were harvested and treated with hypotonic lysis buffer, then DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Donor GFP+ cells were quantified using an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) System (Foster City, CA). GFP-specific forward (5′-GTCCGCCCTGAGCAAAGA-3′) and reverse (5′-TCCAGCAGGACCATGTGATC-3′) primers (Sigma Genosys, St Louis, MO) were designed using Primer Express Version 3 (Applied Biosystems). To quantify the percentage of donor cells present in individual spleen samples, DNA for a standard curve was prepared by making serial dilutions of GFP+ cells into C57BL/6 cells (1% GFP+ to 0.001% GFP+). Each 50-μL PCR reaction contained 50 nM forward primer, 50 nM reverse primer, 0.1 μg DNA, and 25 μL of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). PCR conditions for all samples were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, and then 39 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute.

Determination of N-region addition in the CDR3 region of the TCR

Cytokine-secreting CD4+ memory cells (cultured with donor allogeneic APCs for 39 hours) were identified using Miltenyi Cytokine Secretion Assays (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer's directions. IFNγ+ and IL-4+ CD4+ cells were sorted on a Becton Dickinson FACSAria, using BD FACSDiva Software. Purity of sorted cells was more than 97%. RNA from sorted cells was purified using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). The CDR3 region of the β chain of the T-cell receptor (TCR) was then amplified from 25 ng RNA using the TITANIUM One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and the following primers: Vβ8, 5′-CGACAAGCTTTGGTATCGGCAGGAC-3′; Cβ, 5′-GGGTGAATTCACATTTCTCAGATC-3′ (Sigma Genosys). The PCR product was cut using EcoRI and HindIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), ligated into a pBluescriptII KS− vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and transformed into DH5α. Bacteria was grown on Luria broth (LB) agar (EMD, Gibbstown, NJ) containing X-gal (40 μg/mL), IPTG (10 mM) (Research Products International, Mt Prospect, IL), and 100 μg/mL ampicillin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Plasmid DNA from selected colonies was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ). N-region addition was analyzed using the ImMunoGeneTics IMGT/V-quest application, available online at http://imgt.cines.fr (International ImMunoGeneTics Information System).

Results

Donor cells are present at low levels, similar to human NIMA-expressing maternal cells, in the murine neonatal spleen

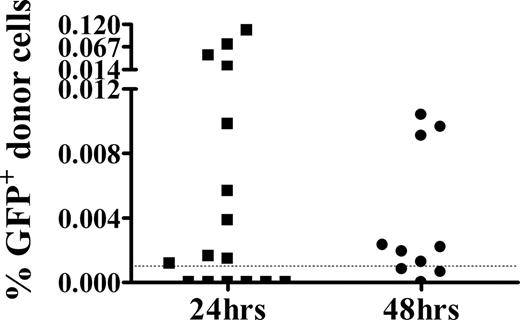

Studies in humans and mice have established that low numbers of NIMA-expressing maternal cells may be present in the periphery shortly after birth.3-9,32-34 In previous studies, we found that transplantation of 1-day-old or younger murine neonates with small numbers of NIMA-like allogeneic cells led to the development of vigorous cytotoxicity.26 To determine whether this system was a reasonable model for the quantity of NIMA exposure that occurs in human infants, the level of donor cells present in the neonatal spleen within 1 or 2 days of injection was assessed. As GFP+ donor cells could not be detected by flow cytometry, potentially due to the low dose of GFP+ cells administered, we used the more sensitive real-time PCR approach. GFP+ donor cells were detected in most neonates (Figure 1) early after injection, at levels (0.001%-0.12%) within the range (0.001%-1%) found in other NIMA studies.2,3,33,35 In addition, the frequency of neonates with detectable levels of GFP+ donor cells was comparable to reported frequencies of humans positive for NIMA-expressing maternal cells.32,33,35

GFP+ donor cells are detectable at NIMA-like levels 24 hours and 48 hours after injection into neonates. BALB/c neonates were injected intravenously with GFP+ adult spleen cells. Twenty-four or 48 hours later, spleens from individual mice were harvested for DNA, which was used in a GFP-specific real-time PCR assay. For quantitation, a standard curve consisting of DNA from a 0.001% to 1% GFP+ cell mixture was generated in parallel. The limit of sensitivity of this assay was 0.001% (dashed line). Individual animals from 3 independent experiments are shown.

GFP+ donor cells are detectable at NIMA-like levels 24 hours and 48 hours after injection into neonates. BALB/c neonates were injected intravenously with GFP+ adult spleen cells. Twenty-four or 48 hours later, spleens from individual mice were harvested for DNA, which was used in a GFP-specific real-time PCR assay. For quantitation, a standard curve consisting of DNA from a 0.001% to 1% GFP+ cell mixture was generated in parallel. The limit of sensitivity of this assay was 0.001% (dashed line). Individual animals from 3 independent experiments are shown.

Exposure to NIMA-like allogeneic cells results in phenotypic changes among neonatal spleen cells

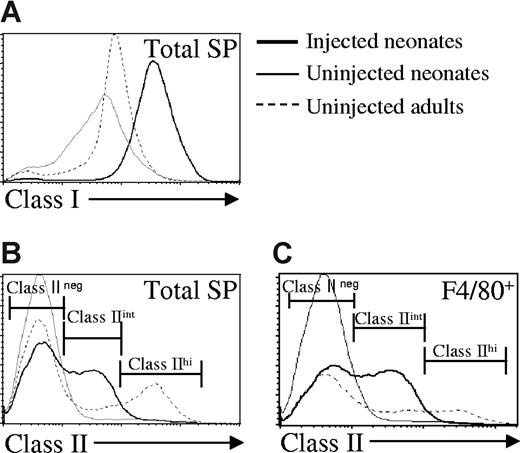

Seven days after injection with allogeneic C57BL/6 adult donor cells, host spleen cells from neonates and adults were analyzed for host-specific MHC expression and APC markers. A dramatic increase in class I MHC expression among the entire host splenic population was observed in neonates exposed to alloantigen, compared with uninjected neonates (Figure 2A). Remarkably, the level of class I MHC expressed on splenocytes from injected neonates was even greater than the expression on spleen cells from adults. In addition to changes in class I MHC, a class IIint population was detected in injected neonates that was not present in either uninjected neonates or adults (Figure 2B). There was no difference in class I or class II expression between injected and uninjected control adults (data not shown).

In vivo exposure to NIMA-like allogeneic cells induces striking phenotypic changes on neonatal spleen cells. Neonatal and adult BALB/c (H-2d) mice were injected with C57BL/6 (H-2b) adult spleen cells, as described in “Preparation and injection of donor cells.” Seven days later, spleen cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. Spleens were pooled from 2 to 3 mice per group. (A) Host-specific class I MHC expression. The depicted histogram is representative of 12 independent experiments. (B) Host-specific class II MHC expression. The histogram shown is representative of 8 independent experiments. (C) Expression of class II MHC on F4/80+ spleen cells. The histograms are representative of 6 independent experiments.

In vivo exposure to NIMA-like allogeneic cells induces striking phenotypic changes on neonatal spleen cells. Neonatal and adult BALB/c (H-2d) mice were injected with C57BL/6 (H-2b) adult spleen cells, as described in “Preparation and injection of donor cells.” Seven days later, spleen cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. Spleens were pooled from 2 to 3 mice per group. (A) Host-specific class I MHC expression. The depicted histogram is representative of 12 independent experiments. (B) Host-specific class II MHC expression. The histogram shown is representative of 8 independent experiments. (C) Expression of class II MHC on F4/80+ spleen cells. The histograms are representative of 6 independent experiments.

Up-regulation of MHC, particularly class II molecules, is a marker of the functional maturation of APC populations (reviewed in Tan and O'Neill36 and Banchereau et al37 ). To identify APC populations that may have undergone functional maturation, neonatal spleen cells from injected and control neonates were stained with antibodies for dendritic cells (CD11c), macrophages (F4/80), and B cells (B220). There was no difference in the number of CD11c+ cells or in the expression of class II MHC on CD11c+ splenocytes from injected and uninjected neonates (Table 1 and data not shown). The expression of class II on neonatal splenic B cells also remained unchanged (data not shown), but there was a reduction in the absolute number of B cells in injected neonates (Table 1). Among F4/80+ cells, class II expression was increased to intermediate levels on approximately half of the population in injected neonates compared with controls (Figure 2C). However, there was no difference in the number of F4/80+ cells in the spleens of injected or control neonates (Table 1). These data suggest that macrophages in injected neonates up-regulate class II and may undergo at least partial functional maturation. Finally, the majority of splenic cells in both injected and control neonates were of erythroid origin (TER-119+).

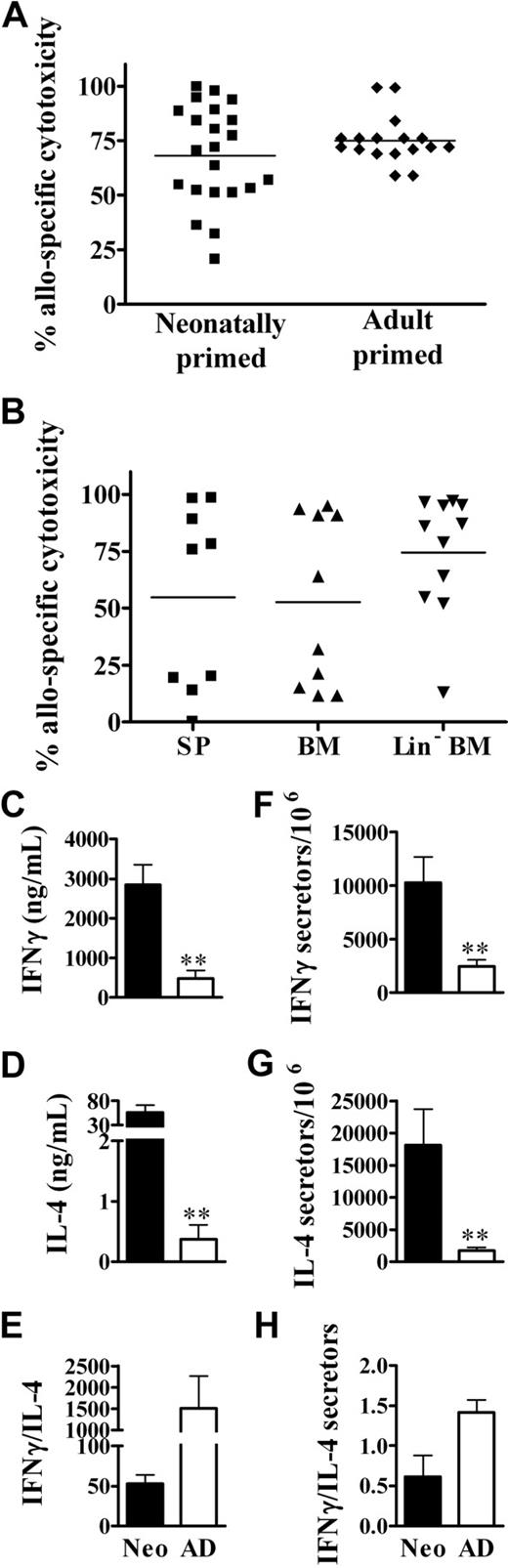

Neonates develop vigorous in vivo cytotoxic and Th memory responses to NIMA-like alloantigens

We previously identified in vitro memory cytotoxic responses in animals injected as neonates with NIMA-like allogeneic cells.26 However, it was important to determine whether memory cytotoxic function would also occur in vivo, as it would in a transplant setting. To test this, BALB/c neonates and adults received a transplant of C57BL/6 spleen cells. Several weeks later, the development of in vivo cytotoxic responses was assayed. Neonatally primed mice displayed memory cytotoxic responses to alloantigens that were similar to those in adult-primed mice (Figure 3A). However, there is evidence that stem cells can cross the placenta and engraft in the fetus.38 This could result in microchimerism, which has been correlated with the development of NIMA-specific tolerance.23 Therefore, we also determined whether exposure to low doses of Lin− BM cells (enriched in hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cell populations39,40 ) in early life results in long-term priming against NIMA-like alloantigens. Similar to responses to total spleen cells, mice exposed as neonates to BM cells developed memory in vivo cytotoxic responses to both unfractionated BM and Lin− BM cells (Figure 3B). This suggests that the dose of maternal cells, regardless of the particular cell type, may be more important for the development of alloantigen-specific cytotoxic responses in neonatal life.

The development of robust in vivo memory cytotoxic and Th1/Th2 responses upon exposure of neonates to NIMA-like alloantigens. (A) Neonates (n = 22) and adults (n = 17) were injected with allogeneic spleen cells, as described for Figure 2. Five to 15 weeks later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in individual spleens was determined as described in “In vivo cytotoxicity assays.” A minimum of 1 × 106 total cells were examined for each sample. Data from individual mice from 3 independent experiments are depicted (variations in responses were observed within each experiment). The average percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity was not significantly different (2-tailed t test) between neonates and adults. (B) Neonates were injected with allogeneic spleen cells (SP), bone marrow (BM), or Lin− BM cells, as described in “Preparation and injection of donor cells.” Five to 6 weeks later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in individual spleens was determined. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 9 for SP, n = 10 for BM, and n = 11 for Lin− BM. The average percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity was not significantly different (2-tailed t test) between groups. (C-H) Neonates and adults were injected with allogeneic cells, as described for Figure 2. Memory CD4+ cytokine responses were then assayed by ELISA (C-E) and the frequency of cytokine-producing memory cells was determined by ELISPOT (F-H), as described in “Culture conditions for cytokine ELISA and ELISPOT.” The in vitro responses of age-matched, naive controls, determined in parallel, were as follows: for neonates: IFNγ, 155 (± 44) ng/mL and 1728 (± 826) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 1.0 (± 0.7) ng/mL and 2113 (± 636) secretors/106 cells; for adults: IFNγ, 187 (± 41) ng/mL and 2146 (± 2112) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 0.28 (± 0.1) ng/mL and 2221 (± 1056) secretors/106 cells. Error bars represent the mean (± SD) of data from 4 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a 2-tailed t test; **P < .005

The development of robust in vivo memory cytotoxic and Th1/Th2 responses upon exposure of neonates to NIMA-like alloantigens. (A) Neonates (n = 22) and adults (n = 17) were injected with allogeneic spleen cells, as described for Figure 2. Five to 15 weeks later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in individual spleens was determined as described in “In vivo cytotoxicity assays.” A minimum of 1 × 106 total cells were examined for each sample. Data from individual mice from 3 independent experiments are depicted (variations in responses were observed within each experiment). The average percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity was not significantly different (2-tailed t test) between neonates and adults. (B) Neonates were injected with allogeneic spleen cells (SP), bone marrow (BM), or Lin− BM cells, as described in “Preparation and injection of donor cells.” Five to 6 weeks later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in individual spleens was determined. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 9 for SP, n = 10 for BM, and n = 11 for Lin− BM. The average percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity was not significantly different (2-tailed t test) between groups. (C-H) Neonates and adults were injected with allogeneic cells, as described for Figure 2. Memory CD4+ cytokine responses were then assayed by ELISA (C-E) and the frequency of cytokine-producing memory cells was determined by ELISPOT (F-H), as described in “Culture conditions for cytokine ELISA and ELISPOT.” The in vitro responses of age-matched, naive controls, determined in parallel, were as follows: for neonates: IFNγ, 155 (± 44) ng/mL and 1728 (± 826) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 1.0 (± 0.7) ng/mL and 2113 (± 636) secretors/106 cells; for adults: IFNγ, 187 (± 41) ng/mL and 2146 (± 2112) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 0.28 (± 0.1) ng/mL and 2221 (± 1056) secretors/106 cells. Error bars represent the mean (± SD) of data from 4 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a 2-tailed t test; **P < .005

Neonates typically mount poor cytotoxic and Th1 memory responses to a wide variety of antigens.16,20,21,41,42 We have observed the development of vigorous cytotoxic memory responses to alloantigen, and cytotoxic responses are typically associated with the development of Th1 responses. Therefore, we determined whether neonates could also develop memory Th1 responses to NIMA-like alloantigens. Surprisingly, the memory IFNγ response of neonatal CD4+ cells to alloantigen was 6-fold greater (P < .005) than that by adult CD4+ cells (Figure 3C). To distinguish whether there were greater numbers of cytokine-secreting cells or whether the amounts of cytokine made per cell were greater for neonates, the frequency of allospecific CD4+ Th1 memory cells in neonatally injected animals was determined. The frequency of IFNγ-secreting CD4+ cells was increased approximately 4-fold in neonates compared with adults (Figure 3F), that is, the fold increase in total IFNγ produced was consistent with the fold increase in cytokine-secreting cells. This contrasts with Th2 cytokine production, in which neonates showed a 10-fold increase in the frequency of IL-4–producing cells (Figure 3G) relative to adults, but showed a striking 151-fold increase in IL-4 production (Figure 3D). Similar results were observed at 48 hours (data not shown). Despite their robust IFNγ production, the relatively greater IL-4 production resulted in an overall Th2 bias in neonates compared with adults, as assessed by cytokine production and the frequency of cytokine-producing cells (Figure 3E,H).

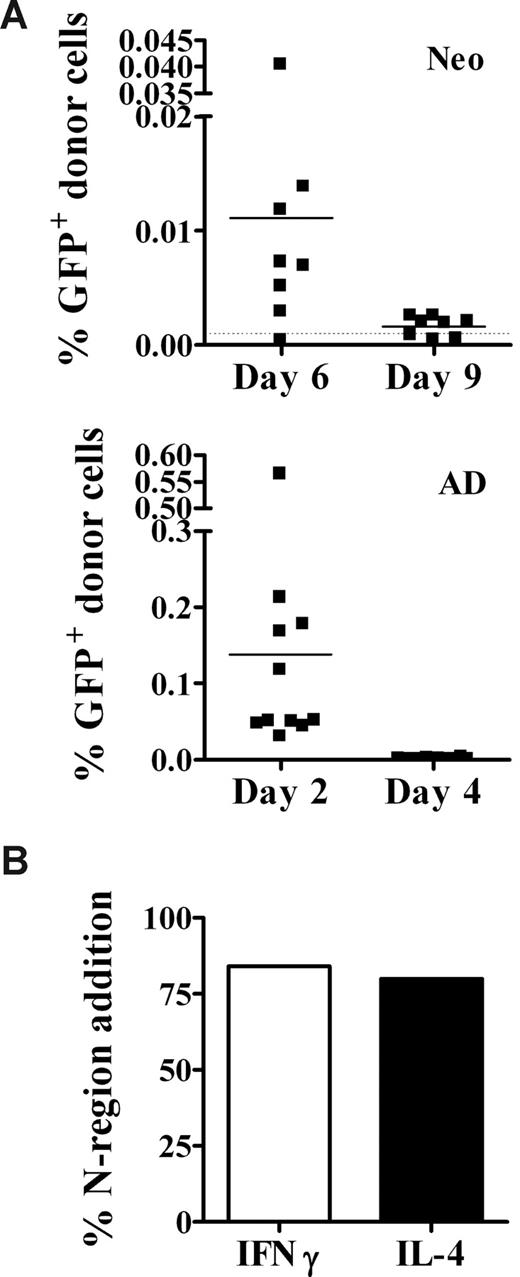

Persistence of donor cells in the neonatal spleen

The vigorous Th1 memory responses in neonates might arise if donor cells persist for longer periods in neonates than in adults. This could lead to the continued recruitment of T cells later in development, which could contribute to the secondary response. To examine this possibility, neonates and adults were injected with GFP+ cells, and spleens were harvested at several time points for DNA. Early after transplantation (day 2), donor cell levels in adults were on average 10-fold higher than in neonates (Figure 4A). This is probably due to the dilution of GFP+ donor cells in the neonatal spleen by the presence of lysis-resistant erythroid-lineage cells (TER119+), which were approximately 8-fold higher in the neonatal (53.5% ± 5.5%) versus the adult (6.6% ± 0.6%) spleen after hypotonic lysis. GFP+ cells were present in adults (Figure 4A bottom panel) on day 2 (n = 11), but were no longer detectable by day 4 (n = 10). In contrast, donor GFP+ cells were detected in almost all neonates for at least 4 days longer, until day 6 (n = 8) after injection, but were no longer detectable by day 9 (n = 8; Figure 4A top panel).

Donor cells persist in the neonate for at least 6 days after injection. (A) Neonates (top panel) and adults (bottom panel) were injected with allogeneic GFP+ cells, as described in Figure 2. Two to 9 days later, spleen cells were harvested for DNA isolation. DNA (0.1 μg) from individual animals was used in a quantitative GFP-specific real-time PCR assay to test for the presence of donor GFP+ cells, as described in Figure 1. The limit of sensitivity (dotted line) for this assay was 0.001%. Data are pooled from 2 to 3 independent experiments. (B) Cytokine-secreting memory CD4+ spleen cells were sorted, and the frequency of N-region addition in the CDR3 region of the TCR was determined as described in “Determination of N-region addition in the CDR3 region of the TCR.” Data represent 19 clones from IFNγ-secreting cells and 24 clones from IL-4–secreting cells.

Donor cells persist in the neonate for at least 6 days after injection. (A) Neonates (top panel) and adults (bottom panel) were injected with allogeneic GFP+ cells, as described in Figure 2. Two to 9 days later, spleen cells were harvested for DNA isolation. DNA (0.1 μg) from individual animals was used in a quantitative GFP-specific real-time PCR assay to test for the presence of donor GFP+ cells, as described in Figure 1. The limit of sensitivity (dotted line) for this assay was 0.001%. Data are pooled from 2 to 3 independent experiments. (B) Cytokine-secreting memory CD4+ spleen cells were sorted, and the frequency of N-region addition in the CDR3 region of the TCR was determined as described in “Determination of N-region addition in the CDR3 region of the TCR.” Data represent 19 clones from IFNγ-secreting cells and 24 clones from IL-4–secreting cells.

Next, we investigated whether the persistence of donor cells leads to the continued recruitment of cells into the Th response. It is reasonable to assume that just after birth, the neonatal peripheral T-cell compartment would be fetal-like, characterized by a low frequency (10%-16%) of cells with N-region addition43 in the CDR3 region of the T-cell receptor (TCR). However, if persistence of donor alloantigen results in the recruitment of adultlike cells into allospecific Th responses, it would be expected that the frequency of allospecific memory Th cells containing N-region addition would be closer to that of adult cells (∼ 88%43 ). Therefore, we sorted cytokine-secreting Th memory cells from neonatally primed mice, and determined the frequency of N-region addition among DNA clones. Consistent with the hypothesis that “mature” cells are recruited into allospecific Th responses, clones from IFNγ-secreting and IL-4–secreting cells displayed an adultlike pattern of N-region addition (Figure 4B). Of note, in contrast to a previous report analyzing a limited number of DNA clones,44 we saw no evidence for sequence motifs particular to only IFNγ- or only IL-4–secreting cells from neonatally primed animals (data not shown).

T-cell responses to NIMA-like alloantigens are established during the neonatal period

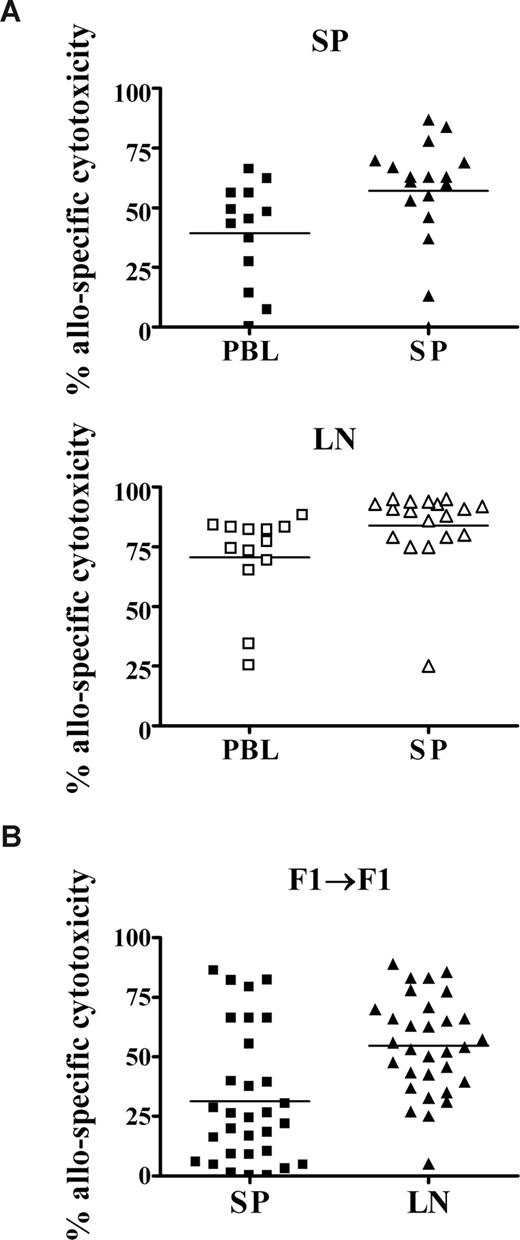

The persistence of donor cells and the adult-like TCR pattern in neonates indicated that memory responses may largely develop after the neonatal period of life. To determine whether neonates were competent to develop alloantigen-specific function within the first week of life, we analyzed their primary responses to allogeneic spleen cells. As fetal NIMA exposure may be to cells that have transferred from maternal peripheral blood, we also examined neonatal primary cytotoxic responses to adult allogeneic peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs). Cytotoxic responses to both allogeneic donor PBLs and donor spleen cells were observed in the neonatal spleen (Figure 5A top panel). As there are proportionately fewer CD8+ T cells in the spleens of 7- to 8-day-old neonates,45,46 but normal percentages in the lymph nodes,30 we also determined the level of allospecific cytotoxicity in the neonatal lymph node. Neonates demonstrated vigorous responses to both allogeneic PBLs and spleen cells in the lymph node (Figure 5A bottom panel). However, most murine NIMA models result in exposure to semiallogeneic maternal cells during early life.13,23,24 To address how contact with semiallogeneic cells in our model would affect cytotoxic responses, we mated C57BL/6 and BALB/c females with FVB males to generate F1 neonates and adults. As observed with the fully allogeneic injection model, neonatal (BALB/c × FVB) F1 mice that received a transplant of low doses of adult (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 spleen cells developed allospecific in vivo cytotoxic responses in both the SP and LN (Figure 5B).

In vivo cytotoxic responses to NIMA-like alloantigens develop during the neonatal period. (A) Neonates were injected with allogeneic adult spleen cells or PBLs. Seven days later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in the spleen (SP) and lymph nodes (LNs) was determined, as described for Figure 3. Data are pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments. (B) (BALB/c × FVB) F1 neonates were injected with semiallogeneic adult (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 spleen cells, as described for Figure 2. Seven days later, neonates were injected with a 1:1 mixture of Far Red–labeled (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 and (BALB/c × FVB) F1 cells, as described in “In vivo cytotoxicity assays.” The percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in the spleen (SP) and lymph nodes (LNs) was determined as described for Figure 3. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments; n = 31 neonates.

In vivo cytotoxic responses to NIMA-like alloantigens develop during the neonatal period. (A) Neonates were injected with allogeneic adult spleen cells or PBLs. Seven days later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in the spleen (SP) and lymph nodes (LNs) was determined, as described for Figure 3. Data are pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments. (B) (BALB/c × FVB) F1 neonates were injected with semiallogeneic adult (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 spleen cells, as described for Figure 2. Seven days later, neonates were injected with a 1:1 mixture of Far Red–labeled (C57BL/6 × FVB) F1 and (BALB/c × FVB) F1 cells, as described in “In vivo cytotoxicity assays.” The percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in the spleen (SP) and lymph nodes (LNs) was determined as described for Figure 3. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments; n = 31 neonates.

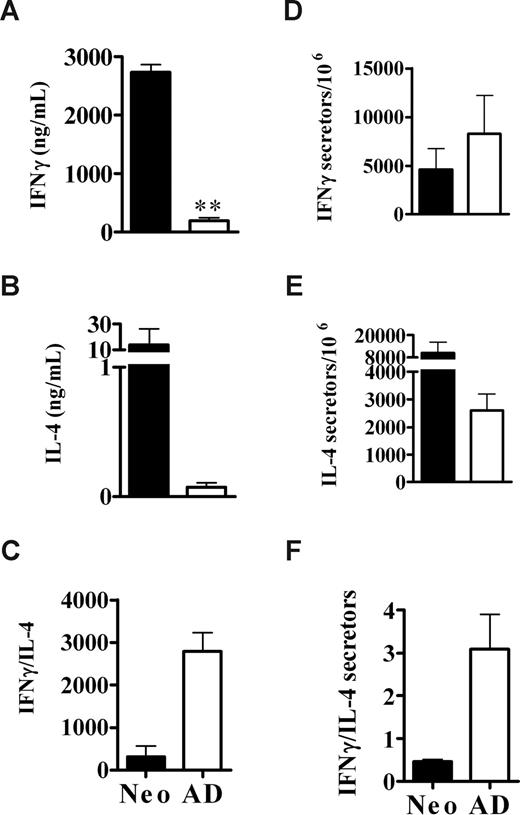

Next, the primary cytokine responses of neonates and adults to alloantigen were assayed to determine whether the robust memory Th1/Th2 responses in neonates were also established in the primary response. There was a 14-fold greater production of IFNγ in injected neonates compared with injected adults (Figure 6A); however, unlike memory responses, the high level of IFNγ production was not associated with a greater frequency of IFNγ-secreting cells (Figure 6D). In contrast, similar to what was observed in the memory response, there was both a greater production of IL-4 (Figure 6B) and a higher frequency of IL-4–secreting cells (Figure 6E) among the neonatal, compared with the adult, population.

Neonates develop vigorous Th1 and Th2 primary responses to NIMA-like alloantigens. Neonates and adults were injected with allogeneic cells, as described for Figure 2. Seven days later, purified CD4+ cells from injected neonates or adults were stimulated with allogeneic APCs and assayed for cytokine production by ELISA after 48 hours (A-C) or frequency of cytokine-producing cells by ELISPOT after 72 hours (D-F) as described in “Culture conditions for cytokine ELISA and ELISPOT.” The in vitro responses of age-matched, naive controls, determined in parallel were as follows: for neonates: IFNγ, 109 (± 145) ng/mL and 1598 (± 534) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 0.17 (± 0.03) ng/mL and 3798 (± 1412) secretors/106 cells; for adults: IFNγ, 9.4 (± 5.6) ng/mL and 1760 (± 339) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 0.024 (± 0.024) ng/mL and 2054 (± 91) secretors/106 cells. Error bars represent the mean (± SD) of data from 2 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a 2-tailed t test; **P = .002

Neonates develop vigorous Th1 and Th2 primary responses to NIMA-like alloantigens. Neonates and adults were injected with allogeneic cells, as described for Figure 2. Seven days later, purified CD4+ cells from injected neonates or adults were stimulated with allogeneic APCs and assayed for cytokine production by ELISA after 48 hours (A-C) or frequency of cytokine-producing cells by ELISPOT after 72 hours (D-F) as described in “Culture conditions for cytokine ELISA and ELISPOT.” The in vitro responses of age-matched, naive controls, determined in parallel were as follows: for neonates: IFNγ, 109 (± 145) ng/mL and 1598 (± 534) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 0.17 (± 0.03) ng/mL and 3798 (± 1412) secretors/106 cells; for adults: IFNγ, 9.4 (± 5.6) ng/mL and 1760 (± 339) secretors/106 cells; IL-4, 0.024 (± 0.024) ng/mL and 2054 (± 91) secretors/106 cells. Error bars represent the mean (± SD) of data from 2 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a 2-tailed t test; **P = .002

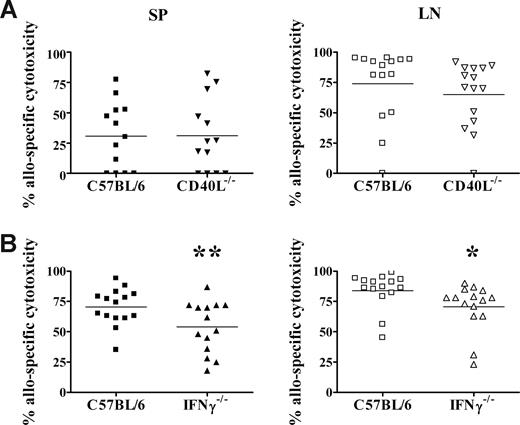

Donor IFNγ secretion contributes to the development of allospecific T-cell responses in neonates

Previously we reported that adult donor CD4+ T cells are necessary for the development of allospecific cytotoxicity in neonates.26 We have also found that live donor cells are required, as irradiated donor cells were unable to induce in vivo cytotoxicity (data not shown). These results suggest that a dynamic signal from living adult T cells may be required for the activation of neonatal CD8+ T cells. We therefore examined whether donor CD40L or IFNγ expression is required for the development of neonatal allospecific T-cell responses. Neonates exposed to CD40L-deficient donor cells (Figure 7A) mounted cytotoxic responses in both the spleen and lymph nodes that were equivalent to the primary responses elicited by wild-type C57BL/6 donor cells. Exposure to CD40L−/− donor cells also induced vigorous Th1 and Th2 memory cytokine responses compared with adults (data not shown). In contrast, neonates that received a transplant of IFNγ−/− donor cells (Figure 7B) developed allospecific cytotoxic responses that were reduced by 23% in the spleen (P = .02) and 16% in the lymph node (P = .04), compared with neonates that received a transplant of wild-type donor cells.

IFNγ production by donor cells contributes to the development of neonatal allospecific cytotoxic responses. Adult C57BL/6 (A,B), CD40L−/− spleen cells (A), or IFNγ−/− spleen cells (B) were transplanted into BALB/c neonates, as described for Figure 2. Seven days later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in the spleen (SP) and lymph nodes (LNs) was determined, as described for Figure 3. Data are pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments. **P = .02; *P = .04, compared with wild-type donor cells by t test.

IFNγ production by donor cells contributes to the development of neonatal allospecific cytotoxic responses. Adult C57BL/6 (A,B), CD40L−/− spleen cells (A), or IFNγ−/− spleen cells (B) were transplanted into BALB/c neonates, as described for Figure 2. Seven days later, the percentage of allospecific cytotoxicity in the spleen (SP) and lymph nodes (LNs) was determined, as described for Figure 3. Data are pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments. **P = .02; *P = .04, compared with wild-type donor cells by t test.

Discussion

Due to a relative developmental delay in immunologic maturity, newborn (∼1 day old) mice most closely resemble humans in utero (reviewed in Siegrist47 ). As the human fetus and mother are antigenically foreign to each other across both major and minor histocompatabilities, we injected 1-day-old murine neonates with fully allogeneic adult donor cells to model the in utero exposure of human fetuses to NIMA. Using this model, the present investigation has demonstrated that exposure to low doses of NIMA-like alloantigens during the neonatal period does not result in immune tolerance. Rather, exposure efficiently induces both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell effector function. Of particular note, this is the first report to show that murine neonates are capable of producing robust and durable in vivo cytotoxic and Th1 responses to alloantigen. Importantly, these responses develop during the neonatal period, when NIMA-expressing maternal cells are known to be present in the murine neonate.2,3 Therefore, neonatal T cells can become primed to NIMA-like alloantigens early in life, and can develop into vigorous memory cytotoxic and Th responses that persist into adulthood. These observations offer a potential explanation for why acute graft rejection is observed in some NIMA transplant settings in humans.22

It is well established that neonatal memory responses to many antigens are often Th2-biased compared with adults, due to high levels of IL-4 and deficient IFNγ production.48-52 Although neonatal memory Th1 responses are typically deficient compared with adults, they can be boosted to adult levels through the use of strong Th1-promoting agents.53-55 However, neonatal levels of IFNγ (in response to antigen) have not been reported to be elevated significantly above adult levels by these Th1-promoting agents. Therefore, the 6-fold greater IFNγ production by memory neonatal T cells compared with adults in response to alloantigen was surprising (Figure 3C). This was accompanied by a modest, yet consistent and statistically significant, increase in the frequency of IFNγ-secreting memory cells in neonatally injected animals, compared with injected adults. The greater IFNγ memory responses were not due to a greater recruitment of Th1 cells during the initial priming, as there were reduced frequencies of IFNγ-secreting allospecific cells in neonates during the primary response (Figure 6D). Therefore, it seems likely that the persistence of donor cells in neonates may contribute to the greater neonatal Th1 memory response. As donor cells were present in neonates at detectable levels for at least 6 days after transplantation (Figure 4A), alloantigen may be present as the neonatal immune system continues to mature. This could allow for a prolonged recruitment of Th1 cells into the response as the T-cell compartment expands and matures. We examined this possibility by measuring the frequency of N-region addition among clones from IFNγ- or IL-4–producing cells. Indeed, the pattern of N-region addition in the TCR CDR3 region of IFNγ-secreting Th1 memory cells was consistent with the idea that adult cells may be recruited into the memory response, although donor cells cannot be detected after 6 days (Figure 4B).

We previously reported that CD4+ donor T cells are required for the development of allospecific cytotoxicity.26 Therefore, we hypothesized that a product of activated donor CD4+ T cells was responsible for the development of neonatal antidonor cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) function. Two potential molecules are CD40L and IFNγ. First, as CD40L is poorly expressed by activated neonatal CD4+ T cells,18,56-60 we hypothesized that mature levels of CD40L on activated donor CD4+ T cells were necessary for the development of neonatal antidonor T-cell responses. However, when neonates were exposed to CD40L−/− donor cells, they were able to develop vigorous antidonor CTL and Th1/Th2 responses (Figure 7A and data not shown), demonstrating that donor CD40L is not necessary for the development of neonatal allospecific T-cell responses. The activation of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the absence of donor CD40L suggests that although CD40L levels may be reduced on activated neonatal T cells, they are sufficient for the development of effector function by neonatal T cells in the context of antigenic stimulation with low doses of NIMA-like alloantigens. The second candidate, IFNγ, has diverse effects on immune cells. This includes up-regulation of class I and class II MHC, activation of macrophages, and the production of IL-12 by APCs (reviewed in Schroder et al61 ). Therefore, we hypothesized that IFNγ secreted by activated donor cells would be necessary for the development of allospecific cytotoxicity. Indeed, although neonates that received a transplant of IFNγ−/− cells developed cytotoxic responses, they were significantly reduced compared with cytotoxic responses that developed upon transplantation with wild-type donor cells (Figure 7B). This suggests that IFNγ secreted by donor cells contributes in part to the development of allospecific cytotoxicity in neonates.

It has been suggested that the dose of cells the fetus and/or neonate is exposed to in early life may determine whether tolerance or priming to NIMA develops (reviewed in Andrassy et al,23 Molitor and Burlingham,25 and Adkins et al26 ). Experimental transplantation of high doses of allogeneic cells results in tolerance,13-21 and there are reports that this effect may be mediated by regulatory T cells (Tregs).62 Recent studies using a NIMA mouse model have demonstrated that mice that accepted allogeneic heart grafts exhibit donor microchimerism,23 and possess higher frequencies of Tregs and TGF-β+IL-10+CD4+ cells than mice that rejected their allografts.23,24 However, tolerance to NIMA-bearing heart allografts was observed only when the mice were exposed to NIMA both in utero and after birth via breast milk.23 Breast milk contains both maternal cells (reviewed in Goldman and Goldblum11 ) and high levels of soluble HLA,12 and is thus a rich source of NIMA postnatally. Therefore, this multiple pathway exposure can be considered a high-dose NIMA exposure, and may lead to the induction of regulatory mechanisms that result in tolerance (reviewed in Molitor and Burlingham25 ). The notion of multiple pathway exposure leading to tolerance is supported by several human transplantation studies, which demonstrated that renal transplant patients who had been breastfed exhibited better survival of both maternal and sibling kidney allografts than those who had not been breastfed.63,64 Therefore, in humans, exposure to high antigenic doses of NIMA-expressing maternal cells or HLA from both in utero and postnatal sources may be necessary for the development of tolerance to NIMA.

Although early life exposure to NIMA can certainly result in the induction of tolerance, there is also evidence for priming to NIMA.22,25,26 In both human and murine NIMA models, some recipients of NIMA-bearing allografts exhibited early, acute rejection episodes, suggesting that priming to NIMA had developed.22,25 The results in this study are consistent with such findings, and support the hypothesis that low-dose exposure to NIMA may result in priming instead of tolerance. Although not examined here, this priming could involve a failure of low doses of NIMA to induce regulatory mechanisms such as Tregs. Clinically, it is possible that low-dose exposure to NIMA could occur among children who are born prematurely and/or not breastfed, and therefore are exposed to only low levels of NIMA in utero. This low-level exposure to NIMA in human children may lead to priming instead of tolerance, and the subsequent development of robust cytotoxic and T-helper responses that could affect the outcome of NIMA-bearing transplants in later life.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Patricia Guevara, Elizabeth Wilcox, Carolina Pilonieta, and Maria Bodero provided excellent technical assistance. DH5α and pBluescript II KS− vector were generously provided by George Munson.

This work was supported by grant AI44923-02 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID, Bethesda, MD; B.A) and grant AI046689 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD; R.B.L.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: S.J.O. designed and performed research, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the paper; R.B.L. contributed to the study design and to the preparation of the paper; and B.A. was responsible for the overall study, designed research, and contributed to the preparation of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Becky Adkins, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 1600 NW 10th Ave, R-138, Miami, FL 33136; e-mail: radkins@med.miami.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented in abstract form at the 94th annual meeting of The American Association of Immunologists, Miami Beach, FL, May 20, 2007.65