Abstract

The anticancer potency of green tea and its individual components is being intensely investigated, and some cancer patients already self-medicate with this “miracle herb” in hopes of augmenting the anticancer outcome of their chemotherapy. Bortezomib (BZM) is a proteasome inhibitor in clinical use for multiple myeloma. Here, we investigated whether the combination of these compounds would yield increased antitumor efficacy in multiple myeloma and glioblastoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Unexpectedly, we discovered that various green tea constituents, in particular (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and other polyphenols with 1,2-benzenediol moieties, effectively prevented tumor cell death induced by BZM in vitro and in vivo. This pronounced antagonistic function of EGCG was evident only with boronic acid–based proteasome inhibitors (BZM, MG-262, PS-IX), but not with several non–boronic acid proteasome inhibitors (MG-132, PS-I, nelfinavir). EGCG directly reacted with BZM and blocked its proteasome inhibitory function; as a consequence, BZM could not trigger endoplasmic reticulum stress or caspase-7 activation, and did not induce tumor cell death. Taken together, our results indicate that green tea polyphenols may have the potential to negate the therapeutic efficacy of BZM and suggest that consumption of green tea products may be contraindicated during cancer therapy with BZM.

Introduction

Herbal supplements are commonly perceived as “innocent” or “holistic” and have become hugely popular as unrestrictedly available, over-the-counter, cure-all remedies. Cancer patients in particular may be tempted to self-medicate with such supplements in hopes to delay the progression of their disease and/or reduce the side effects associated with conventional chemotherapy,1-3 and they may do this unbeknownst to their health care providers.2,3 One very popular herb is green tea, brewed from the leaves of the plant Camellia sinensis, which appears to be an ideal alternative medicine because it is nontoxic and shown to have cardioprotective, neuroprotective, anti-infective, and antitumoral properties.4-10 Green tea products are also available as highly concentrated extracts, which can be easily accessed by the public at local grocery, pharmacy, and health food stores throughout the United States

Green tea is a heterogeneous product that contains several antioxidant compounds, known as polyphenols. (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), (-)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), (-)-epigallate catechin (EGC), and (-)-epicatechin (EC) are some of the polyphenol compounds found in green tea.9 EGCG, the most bioactive green tea polyphenol, was demonstrated to be a multipotent chemopreventive and anticancer agent in several animal models, including leukemia, lung, prostate, colon, and breast cancer.9,11-15 It was shown to interact with numerous protein targets and to disrupt biologic/biochemical reactions involved in cancer progression. The EGCG compound can vary its chemical conformation, thus allowing it to behave as a chemical chaperone that is able to interact with an assortment of biologic molecules including DNA, RNA, lipids, and proteins.16 However, it is not entirely clear which of the many functions of EGCG are the most critical with regards to this compound's anticancer activity.

Bortezomib (BZM; Velcade, PS-341) has been approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma, and is being investigated for the potential therapy of other tumors as well.17,18 It functions as a selective inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, a multisubunit protein complex that is responsible for the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins that are marked for deletion from the cell's inventory.19 Proteasome inhibition generates several consequences. For example, it may cause increased levels of biologically active proteins, such as IκB, which is the inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB).20 In addition, misfolded and other obsolete proteins accumulate as well and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), which entails endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.21

ER stress represents a cellular yin-and-yang system. On one side, it restores homeostasis and thereby supports cell survival during low to moderate stress conditions; on the other side, it initiates apoptosis in cases of severe stress, such as in response to the effective inhibition of proteasome activity by bortezomib.22,23 A key prosurvival regulator of the ER stress response is GRP78 (glucose-regulated protein 78 kDa; also called BiP), a chaperone protein with several antiapoptotic functions, which among them features binding to and prevention of caspase-7 activation.24 Earlier reports have clearly established that increased levels of GRP78 provide chemoresistance to tumor cells, and therefore, inhibition of this protein may provide an attractive means to achieve chemosensitization.25

One of several recognized functions of EGCG is its ability to bind to and inhibit GRP78 activity,26 and this interaction may underlie EGCG's reported ability to sensitize tumor cells to killing by the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide or the alkylating agent temozolomide.26,27 Based on these encouraging earlier findings, we initiated a study to investigate whether EGCG and other green tea constituents would be able to enhance the antitumor effects of bortezomib. However, to our surprise, we discovered severe antagonism during combination drug treatments, that is, EGCG or green tea extract effectively blocked proteasome inhibition by bortezomib and thereby prevented ER stress and subsequent tumor cell death in vitro and in vivo. Because the extremely potent blockage of bortezomib's tumoricidal potential was accomplished at concentrations of EGCG that are easily achievable in humans, our results strongly suggest that patients undergoing bortezomib therapy avoid green tea products.

Methods

Materials

Bortezomib (3.5 mg) was obtained from the pharmacy (Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA) and suspended in 3.5 mL saline. Pure bortezomib (> 99%) was purchased from Chemie Tek (Indianapolis, IN). Nelfinavir was obtained from the pharmacy and suspended in DMSO at 50 mM. MG-132 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was dissolved in DMSO at 10.5 mM. MG-262 and proteasome inhibitor IX (PS-IX; EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ) were dissolved in DMSO at 203.5 μM and 26.5 mM, respectively. Proteasome inhibitor I (PS-I; Bachem, Weil am Rhein, Germany) was dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM. EGCG, EGC, ECG, and EC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, dissolved in ultrapure water, and used fresh (or stored at −80°C). TEAVIGO-EGCG are capsules with caffeine-free, highly concentrated green tea extract (≥ 94% EGCG) that are widely available at health food stores28 ; the capsule contents were dissolved in ultrapure water and used fresh (or stored at −80°C). Complete green tea extract in concentrated liquid form (Nature's Answer, Hauppauge, NY) was purchased from a health food store; the amount of this liquid added to cell culture was calculated based on its label claim of 30% EGCG.

Cell lines and culturing

Human MM cell lines RPMI/8226 and U266 were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and MM1 cells were kindly provided by Dr Nancy Krett (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL). All MM cell lines were propagated in RPMI-1640 (Cellgro, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Human glioblastoma cell lines (LN229 and U251) were kindly supplied by Dr Frank Furnari (Ludwig Institute of Cancer Research, La Jolla, CA) and propagated in DMEM (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cell lines were grown with 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C and a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

MTT assay

MTT assays were performed in 96-well plates with the use of 3.0 × 103 cells per well for glioblastoma cells and 2.5 × 104 cells per well for multiple myeloma cells as described in detail elsewhere.29 In individual experiments, each treatment condition was set up in quadruplicate, and each experiment was repeated 1 to 5 times independently.

Colony-formation assay

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 200 cells per well. After complete cell adherence, the cells were exposed to drug treatment for 48 hours (in triplicate). Thereafter, the drug was removed, fresh growth medium was added, and the cells were kept in culture undisturbed for 12 to 14 days, during which time the surviving cells spawned a colony of proliferating cells. Colonies were visualized by staining for 4 hours with 1% methylene blue (in methanol) and then counted.

Apoptosis measurements

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)–mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) detection kit was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) and used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblots and antibodies

Preparation of cell lysates and determination of protein concentration was performed as described before.29 Lysate (50 μg) from each sample was run in parallel. The primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions. The blocking buffer and fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE) and used according to protocols supplied by the manufacturer. The membranes were scanned and analyzed with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All immunoblots were repeated at least once.

Proteasome activity assay

Proteasome activity was determined in 2 different ways, either in lysates from drug-treated cells (whole-cell activity) or via the direct addition of drugs to purified proteasomes. For whole-cell proteasome activity, RPMI/8226 or LN229 cells were treated with various drug combinations for up to 30 hours and then disrupted by vortexing in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer.29 Proteasome activity in 100 μg total cell lysate was measured using a 20S proteasome activity assay kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For purified proteasome activity, various concentrations of bortezomib were mixed with 5 μM EGCG in proteasome assay buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.05% NP-40, and 0.001% SDS [wt/vol]), incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT), and then added to 0.2 μg isolated 20S proteasomes (Sigma-Aldrich). After 5-minute incubation at room temperature, proteasome activity was measured using a 20S proteasome activity assay kit. The emitted fluorescence of cleaved proteasome substrate (LLVY-AMC) was detected with a 380/460-nm filter. Cleaved LLVY-AMC is indicative of chymotryptic activity.

Alizarin red S assay

The alizarin red S (ARS) assay is an optical reporter assay that is widely used to study the binding events between boronic acids and a wide range of molecules harboring 1,2-benzene diol (catechol) moieties.30 Its principle is based on the binding of boronic acid to the catechol unit of the ARS molecule, which results in corresponding alterations of its color and fluorescence, which can be recorded and quantitated. We used this assay as a 3-component competition system of ARS, boronic acid (ie, bortezomib), and a second 1,2-benzene molecule (ie, EGCG). Several repetitions with varying concentrations of the individual components were performed, and binding intensity was measured via readings of optical density (450 nm) and/or fluorescence in a 96-well plate reader. Some of the repetitions were also performed with TEAVIGO-EGCG (and yielded essentially the same results).

Drug treatment of nude mice

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Southern California, and all applicable policies were strictly observed during the course of this study. Four- to 6-week-old male athymic nu/nu mice were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and implanted subcutaneously with 5 × 106 RPMI/8226 multiple myeloma cells. Once tumors of approximately 300 mm3 had developed, the mice received drug treatments. Bortezomib was given as a single dose via intraperitoneal injection. EGCG was given as a single dose via direct administration into the stomach with a stainless steel ball-head feeding needle (Popper and Sons, New Hyde Park, NY). After a total of 72 hours, the mice were killed and tumors were collected for analysis. The mice were closely monitored with regard to body weight, food consumption, and clinical signs of toxicity; no differences between non–drug-treated control animals and drug-treated animals were detected within these parameters.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Frozen tissue sections (7-μm-thick) on glass slides (VWR, Media, PA) were fixed in acetone (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes. The tissue sections were allowed to dry for 10 minutes and then immediately stained with Mayer hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) for another 10 minutes. Afterward, the slides were rinsed in tap water and then stained with eosin (Surgipath, Richmond, IL) for 10 seconds. The slides were then dehydrated in 95% and 100% ethanol in succession for 10 seconds followed by a 30-second incubation in xylene (Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, the slides were mounted on glass coverslips, sealed with nail polish, and analyzed under the microscope. Stained tumor sections were visualized using the Leica DM LB2 universal system microscope (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) at 200× magnification. Images were acquired with the Spot RT color camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and Spot 4.2 software.

Results

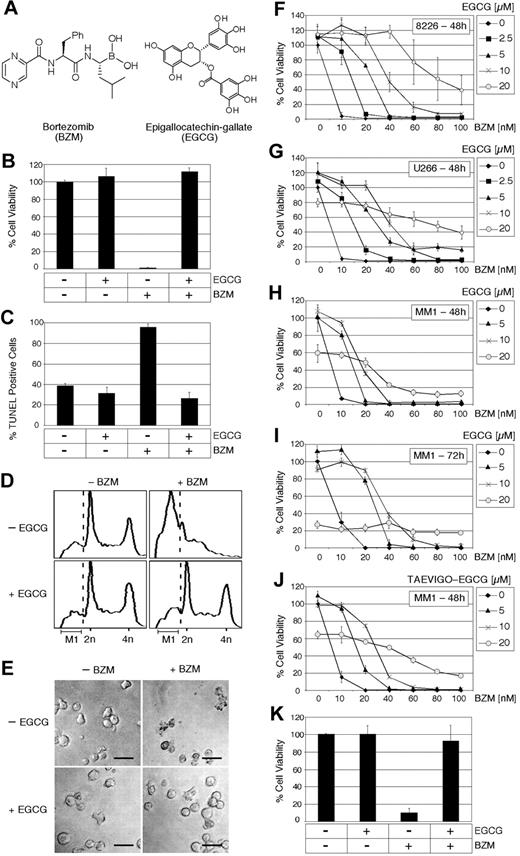

EGCG blocks the cytotoxic effects of BZM in multiple myeloma cells

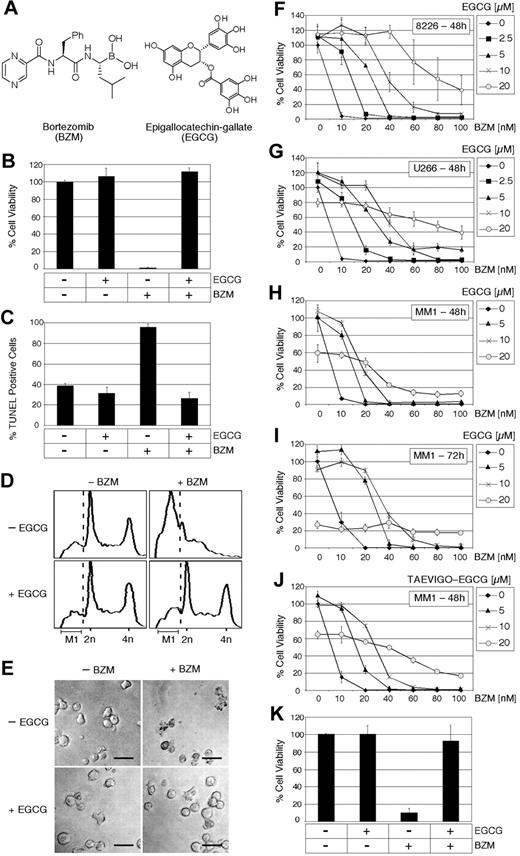

To investigate whether the cytotoxic effects of BZM could be affected by the addition of EGCG (see Figure 1A for chemical structures), we treated different multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines with these agents alone or in combination and determined cell growth and survival by various assays. MTT assay of RPMI/8226 cells revealed that 10 nM BZM effectively killed the entire cell culture within 48 hours, whereas over the same time period 10 μM EGCG alone had no effect on cell survival. Surprisingly, however, when BZM and EGCG were added together, the cell killing by BZM was completely prevented and cell survival remained at 100% (Figure 1B). A similar protective effect of EGCG was noticed when the extent of apoptosis was investigated by TUNEL assay. Here, the addition of BZM increased the amount of cell death to nearly 100%, and this increase was effectively and completely blocked by the addition of EGCG (Figure 1C). Furthermore, cell cycle analysis of untreated cells revealed the typical distribution of a proliferating cell culture across G1, S, and G2/M, with a small fraction (17%) undergoing cell death (indicated by the presence of cells within gate M1 to the left of the dotted line in Figure 1D). Upon the addition of BZM, the normal cell cycle distribution disappeared and the majority of cells (65%) shifted into M1. In stark contrast, however, this effect was effectively blocked by EGCG; that is, when EGCG and BZM were added together, the treated cell culture maintained its normal cell cycle distribution and the fraction of dying cells (M1) remained at the basal level (Figure 1D). This comprehensive cytoprotective effect of EGCG was also verified by microscopic inspection of cell cultures, where the apoptotic phenotype could be clearly observed in the presence of BZM, but was entirely absent when EGCG was added as well (Figure 1E).

EGCG neutralizes the cytotoxic effects of BZM in multiple myeloma cells. (A) Chemical structures of Bortezomib (BZM) and (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). (B) Percentage cell viability of RPMI/8226 cells was determined via MTT assay after 48 hours of treatment with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 μM EGCG. (C) Percentage apoptotic cells was determined via TUNEL staining of slides prepared from RPMI/8226 cells treated for 48 hours with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 μM EGCG. (D) Cell-cycle distribution of cells treated with 20 nM BZM and/or 20 μM EGCG for 24 hours was determined by flow cytometry analysis.31 Distribution of cells left of the dotted line (M1) indicates apoptotic or sub-G1/G0 cells. Cells in G1 display 2n DNA content (x-axis) and those in G2/M display 4n. Y-axis is relative number of cells. (E) Microphotographic images were taken of RPMI/8226 cells after 24 hours of treatment with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 μM EGCG. (F-J) Percentage cell viability of RPMI/8226, U266, and MM1 cells treated for 48 or 72 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGCG or TEAVIGO-EGCG as determined via MTT assay. The percentage survival of nontreated cell cultures was set to 100%; shown is mean ± SE (n ≥ 4). Low concentrations of EGCG may increase the viability of a cell culture to more than 100%; this may be due to a slight reduction of the high basal level of apoptosis, which is present even in nontreated cell cultures (C,D). (K) Patient MM cells were purified from bone marrow aspirates as described32 and analyzed by MTT assay as detailed in panel B. Shown is the average of 4 measurements from 2 independent tissue samples (mean ± SE).

EGCG neutralizes the cytotoxic effects of BZM in multiple myeloma cells. (A) Chemical structures of Bortezomib (BZM) and (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). (B) Percentage cell viability of RPMI/8226 cells was determined via MTT assay after 48 hours of treatment with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 μM EGCG. (C) Percentage apoptotic cells was determined via TUNEL staining of slides prepared from RPMI/8226 cells treated for 48 hours with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 μM EGCG. (D) Cell-cycle distribution of cells treated with 20 nM BZM and/or 20 μM EGCG for 24 hours was determined by flow cytometry analysis.31 Distribution of cells left of the dotted line (M1) indicates apoptotic or sub-G1/G0 cells. Cells in G1 display 2n DNA content (x-axis) and those in G2/M display 4n. Y-axis is relative number of cells. (E) Microphotographic images were taken of RPMI/8226 cells after 24 hours of treatment with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 μM EGCG. (F-J) Percentage cell viability of RPMI/8226, U266, and MM1 cells treated for 48 or 72 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGCG or TEAVIGO-EGCG as determined via MTT assay. The percentage survival of nontreated cell cultures was set to 100%; shown is mean ± SE (n ≥ 4). Low concentrations of EGCG may increase the viability of a cell culture to more than 100%; this may be due to a slight reduction of the high basal level of apoptosis, which is present even in nontreated cell cultures (C,D). (K) Patient MM cells were purified from bone marrow aspirates as described32 and analyzed by MTT assay as detailed in panel B. Shown is the average of 4 measurements from 2 independent tissue samples (mean ± SE).

The sweeping cytoprotective effect of EGCG could also be documented at variable concentrations of each compound and in different MM cell lines (Figure 1F-J). For example, EGCG as low as 2.5 or 5.0 μM (which can easily be achieved in the blood of humans33 ) effectively blocked BZM (10 nM) cytotoxicity by 80% to 100% in RPMI/8226, U266, and MM1 cell lines (Figure 1F-H). The protective effect of EGCG could also be observed at increased concentrations of each drug; for example, when BZM concentrations were quadrupled to 40 nM, the presence of 10 μM EGCG reduced cell killing by 50% in RPMI/8226 cells; and even at 10-fold increased BZM concentrations (100 nM), 20 μM EGCG was still able to significantly reduce cell killing by 40% (Figure 1F). Thus, in this latter example, the cytotoxic IC50 of BZM increased by an order of magnitude from 5 nM to more than 80 nM.

Earlier reports34,35 had indicated that EGCG alone may have cytotoxic effects on MM cell lines when applied at concentrations of 10 μM or higher (which are much greater than the typical concentrations achieved in humans). In comparison, we noted only weak cytotoxic effects starting at 20 μM, which become somewhat more pronounced when drug exposure times are increased from 48 to 72 hours (Figure 1H,I). Interestingly, even under conditions where EGCG is slightly toxic, it is still able to potently antagonize the cytotoxic effects of BZM. For example, in U266 cells, 20 μM EGCG alone reduces viability by 20% after 48 hours, and 10 nM BZM reduces viability by more than 95%—yet, when the 2 drugs are combined, viability is still reduced by only 20% (Figure 1G).

Many of the experiments in this study were repeated with a different EGCG preparation, called TEAVIGO-EGCG,28 that is sold in capsules from health food stores. In all cases, TEAVIGO-EGCG yielded very similar results (Figure 1J). Moreover, when 2 primary tissue samples from MM patients were analyzed, we obtained essentially the same outcome as shown with our MM cell lines, namely, that EGCG provided highly effective protection from the cytotoxic effects of BZM (Figure 1K).

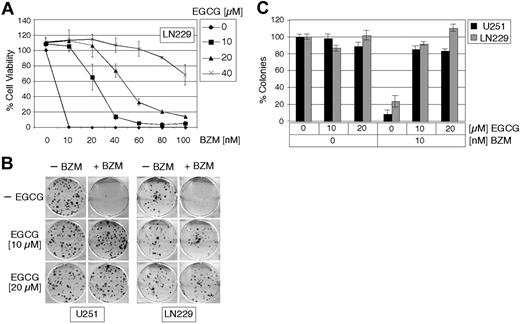

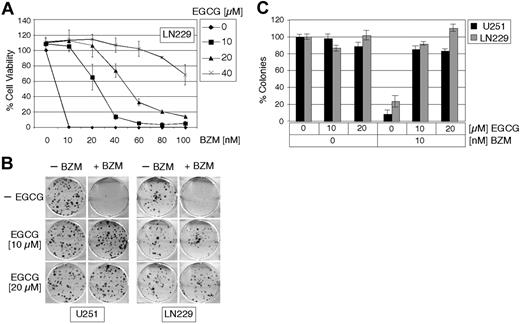

EGCG blocks the cytotoxic effects of BZM in glioblastoma cell lines

BZM is currently being investigated for the treatment of cancers other than multiple myeloma. We therefore set out to determine whether EGCG could neutralize BZM cytotoxicity in 2 glioblastoma cell lines, U251 and LN229. In addition to the conventional MTT assay that determines growth and survival of the entire cell culture during short-term treatments (48 hours), we also performed colony-formation assays (CFAs), which revealed the long-term (2 weeks) survival of individual cells and their ability to spawn a colony of descendants. Figure 2A shows the outcome of MTT assays with LN229 glioblastoma cells, which essentially recapitulated the results obtained with the multiple myeloma cells shown in Figure 1, that is, the presence of EGCG effectively blocked the cytotoxic activity of BZM; in this case, the IC50 of BZM was increased from 5 nM to 25, 50, and more than 100 nM in the presence of 10, 20, or 40 μM EGCG, respectively.

EGCG neutralizes the cytotoxic effects of BZM in glioblastoma. (A) Percentage cell viability of LN229 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGCG was determined via MTT assay. (B) U251 and LN229 were treated with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 or 20 μM EGCG for 48 hours and the number of long-term surviving cells (2 weeks) was determined by colony-formation assays. Images were taken of representative 6-well plates. (C) The average number of colonies of U251 and LN229 cells treated with BZM in the presence or absence of EGCG is presented as the percentage of colonies from untreated cells, which was set at 100% (mean ± SE; n ≥ 3).

EGCG neutralizes the cytotoxic effects of BZM in glioblastoma. (A) Percentage cell viability of LN229 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGCG was determined via MTT assay. (B) U251 and LN229 were treated with 10 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 10 or 20 μM EGCG for 48 hours and the number of long-term surviving cells (2 weeks) was determined by colony-formation assays. Images were taken of representative 6-well plates. (C) The average number of colonies of U251 and LN229 cells treated with BZM in the presence or absence of EGCG is presented as the percentage of colonies from untreated cells, which was set at 100% (mean ± SE; n ≥ 3).

The cytoprotective effect of EGCG toward BZM was also verified in CFA. Figure 2B shows an example of the actual colonies that formed after drug treatment, whereas Figure 2C displays the quantitative analysis of several repetitions of this experiment. As can be seen in both glioblastoma cell lines LN229 and U251, only a very small number of colonies formed after treatment with BZM; but when cells were treated with BZM in the presence of EGCG, the number of colonies was nearly as high as those in the untreated control group (Figure 2B,C). Thus, the antagonistic characteristic of BZM and EGCG treatment could also be documented in adherently growing cell lines representing a solid tumor type.

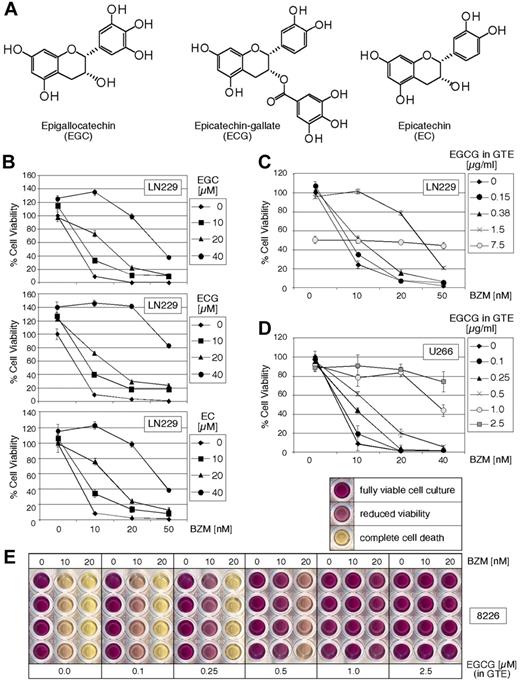

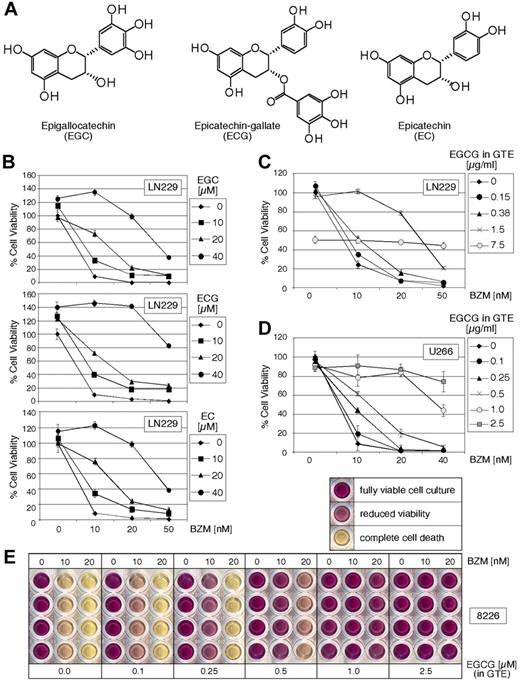

Other polyphenols and complete green tea extract neutralize the cytotoxic effects of BZM

In addition to EGCG, green tea contains various other polyphenol compounds, including EGC, ECG, and EC (Figure 3A). To determine whether complete green tea extract and individual polyphenols other than EGCG can neutralize the cytotoxic effects of BZM, the effect of these combinations on cell growth and survival was investigated by MTT assays. As shown in Figure 3B, each individual green tea polyphenol (EGC, ECG, EC) was able to neutralize the cytotoxic effects of BZM. In comparison with EGCG, however, cytoprotection by these 3 polyphenols against BZM was noticeably weaker. Whereas 10 μM EGCG was able to provide 100% protection against 10 nM BZM (Figures 1,2A), these 3 polyphenols required higher concentrations to achieve the same degree of cytoprotection (Figure 3B).

Complete green tea extract and its polyphenols EGC, ECG, and EC neutralize the cytotoxic effects of BZM. (A) Chemical structures of the green tea polyphenols EGC, ECG, and EC. (B) Percentage cell viability of LN229 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGC, ECG, and EC was determined by MTT assay. Percentage cell viability of (C) LN229 and (D) U266 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of complete green tea extract (GTE) was determined via MTT assay. In all cases, the average percentage of nontreated cell cultures was set to 100%; shown is mean plus or minus SE (n ≥ 4). (E) Typical result of MTT survival assay of RPMI/8226 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of complete GTE. Shown are wells from a 96-well plate, and each condition is shown in quadruplicate. Deep purple color represents fully viable cell culture; pink(ish) color indicates reduced viability; yellow color indicates absence of viable cells. The concentration of EGCG noted in panels C through E was calculated based on the percentage of EGCG as listed on the label of the liquid GTE (“Materials”).

Complete green tea extract and its polyphenols EGC, ECG, and EC neutralize the cytotoxic effects of BZM. (A) Chemical structures of the green tea polyphenols EGC, ECG, and EC. (B) Percentage cell viability of LN229 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGC, ECG, and EC was determined by MTT assay. Percentage cell viability of (C) LN229 and (D) U266 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of complete green tea extract (GTE) was determined via MTT assay. In all cases, the average percentage of nontreated cell cultures was set to 100%; shown is mean plus or minus SE (n ≥ 4). (E) Typical result of MTT survival assay of RPMI/8226 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of complete GTE. Shown are wells from a 96-well plate, and each condition is shown in quadruplicate. Deep purple color represents fully viable cell culture; pink(ish) color indicates reduced viability; yellow color indicates absence of viable cells. The concentration of EGCG noted in panels C through E was calculated based on the percentage of EGCG as listed on the label of the liquid GTE (“Materials”).

We next investigated the effects of a complete green tea extract (GTE) purchased from a health food store as a concentrated liquid, which represents a mixture of the aforementioned polyphenols and other ingredients naturally present in green tea. Liquid GTE was added to LN229 glioblastoma, as well as U266 and RPMI/8226 MM cells, over a range of concentrations providing EGCG from 0.1 to 7.5 μg/mL (equivalent to 0.22-16.6 μM), and its impact on BZM cytotoxicity was investigated by MTT assays. As seen before with individual polyphenols, increasing concentrations of GTE exerted increasing and very effective protection from the cytotoxic effects of BZM (Figure 3C-E). At the highest concentration of GTE (equivalent to 7.5 μg/mL EGCG), some cytotoxic effects of GTE became apparent; however, despite a 50% reduction of viability by GTE alone, the further addition of BZM, even at 50 nM, could not reduce viability further (Figure 3C). Thus, similar to the individual polyphenols tested, complex GTE was able to provide effective protection against BZM, even when its concentration was increased to the point where it became somewhat toxic by itself.

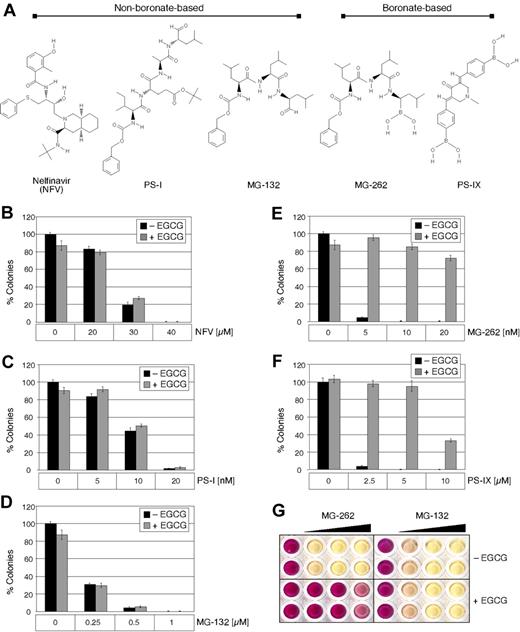

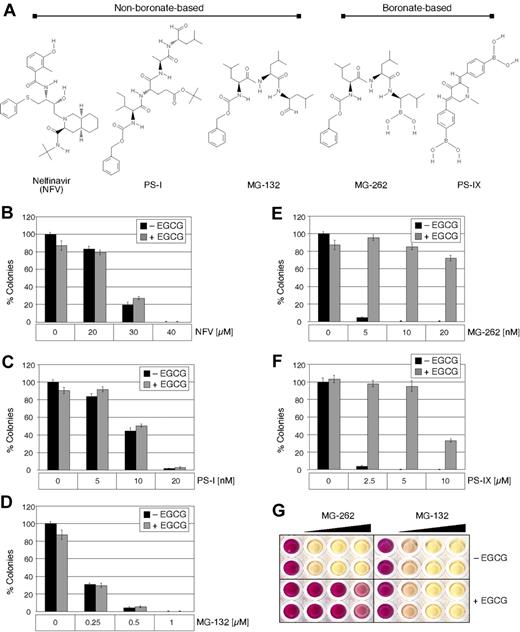

EGCG differentially affects cytotoxicity of various proteasome inhibitors

To determine whether EGCG can neutralize the cytotoxic effects of proteasome inhibitors other than BZM, we included 2 different categories of such compounds in our analysis (see Figure 4A for chemical structures). The first group contained MG-262 and PS-IX, which represent compounds harboring a boronic acid moiety (such as BZM). The second group contained MG-132, PS-I, and nelfinavir (NFV), representing compounds without a boronic acid moiety. (NFV is a clinically used HIV protease inhibitor that is known to also block proteasome function.36 ) The inclusion of MG-132 and MG-262 was expected to be particularly revealing, as these 2 compounds differ only in the presence/absence of the boronic acid moiety.

EGCG neutralizes the cytotoxic effect of MG-262 and proteasome inhibitor IX but not NFV, MG-132, and proteasome inhibitor I. (A) Chemical structures of the proteasome inhibitors NFV, proteasome inhibitor I (PS-I), MG-132, MG-262, and proteasome inhibitor IX (PS-IX), and their grouping according to the presence of a boronic acid. (B-F) LN229 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the individual proteasome inhibitors in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG for 48 hours; thereafter, the number of long-term surviving cells that were able to spawn colonies during the following 2 weeks (in the absence of drug treatment) was determined by colony-formation assays. Shown is the mean plus or minus SE (n ≥ 3). (G) Typical result of MTT survival assay of LN229 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of either MG-262 or MG-132. Shown are wells from a 96-well plate. Deep purple color represents fully viable cells; pink(ish) color indicates reduced viability; yellow indicates absence of viable cells.

EGCG neutralizes the cytotoxic effect of MG-262 and proteasome inhibitor IX but not NFV, MG-132, and proteasome inhibitor I. (A) Chemical structures of the proteasome inhibitors NFV, proteasome inhibitor I (PS-I), MG-132, MG-262, and proteasome inhibitor IX (PS-IX), and their grouping according to the presence of a boronic acid. (B-F) LN229 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the individual proteasome inhibitors in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG for 48 hours; thereafter, the number of long-term surviving cells that were able to spawn colonies during the following 2 weeks (in the absence of drug treatment) was determined by colony-formation assays. Shown is the mean plus or minus SE (n ≥ 3). (G) Typical result of MTT survival assay of LN229 cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence of increasing concentrations of either MG-262 or MG-132. Shown are wells from a 96-well plate. Deep purple color represents fully viable cells; pink(ish) color indicates reduced viability; yellow indicates absence of viable cells.

Each proteasome inhibitor was added to cells at increasing concentrations, in the presence or absence of EGCG, and cell survival was determined by CFA. As shown in Figure 4, all 5 proteasome inhibitors displayed highly cytotoxic effects. In the case of the 3 proteasome inhibitors lacking a boronic acid moiety (MG-162, PS-I, NFV), the addition of EGCG did not at all interfere with their severe cytotoxic efficacy (Figure 4B-D). In contrast, and as observed before with BZM, EGCG provided profound (close to 100%) protection against the proteasome inhibitors that were based on boronic acid (MG-262, PS-IX; Figure 4D,E). For example, 10 nM MG-262 or 5 μM PS-IX reduced colony formation by 100%, but this extremely severe cytotoxic effect was nearly completely prevented by the presence of EGCG. Thus, the protective feature of EGCG is not a general effect toward all proteasome inhibitors, but rather displays selectivity toward those compounds harboring a boronic acid moiety.

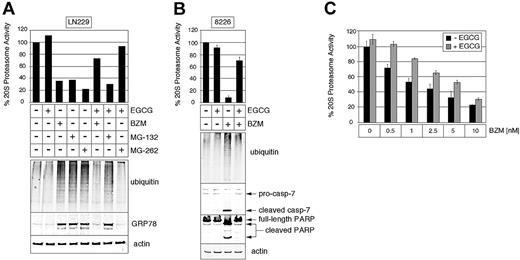

EGCG prevents proteasome inhibition and ER stress induction when combined with boronic acid–based compounds

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms by which EGCG exerted its robust cytoprotective effect against boronic acid–based proteasome inhibitors, we directly investigated the consequences for (1) proteasome inhibition and (2) induction of ER stress, which represents one of the critical proapoptotic processes mediating cell death initiated by proteasome inhibition.22,23 Multiple myeloma RPMI/8226 cells and glioblastoma LN229 cells were investigated in parallel.

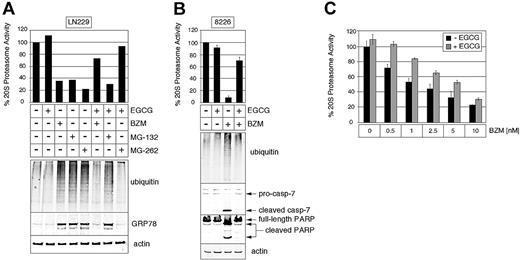

The drug effects on cellular proteasome activity were determined by different approaches: (1) directly via the measurement of proteasome activity, either in lysates from drug-treated cells or with purified 20S proteasomes, and (2) indirectly via Western blot analysis of ubiquitinated proteins, which accumulate when proteasome activity is inhibited. As shown in Figure 5A and B (top panels), treatment of cells with BZM, MG-132, or MG-262 alone resulted in pronounced reduction of proteasome activity; at the same time, there was a marked accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (bottom panels of Figure 5A,B), confirming the biologic consequence of proteasome inhibition. When EGCG was included in these drug treatments, proteasome inhibition and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins were prevented in the case of BZM and MG-262 (boronic acid–based compounds), but not in the case MG-132 (similar to MG-262, but lacking the boronic acid moiety).

EGCG prevents proteasome inhibition and ER stress induction when combined with BZM and MG-262, but not MG-132. (A) LN229 cells were cultured for 30 hours with 20 nM BZM, 1.5 μM MG-132, or 20 nM MG-262 in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG. (Top) Percentage proteasome activity in total cell lysates was determined via 20S proteasome activity assay. (Bottom) The relative amount of polyubiquitinated proteins and the ER stress marker GRP78 was determined via Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against ubiquitin and GRP78, respectively. Western blot to actin was used as a loading control. (B) RPMI/8226 cells were cultured for 30 hours with 20 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG. (Top) Percentage proteasome activity from total cell lysates was determined via 20S proteasome activity assay. (Bottom) The relative amount of polyubiquitinated proteins, activated caspase-7 (cleaved casp-7), and cleavage of poly (ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP, which indicates ongoing apoptosis) in RPMI/8226 cells was determined via Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against ubiquitin, caspase-7, and PARP, respectively. (C) Highly purified proteasomes were treated with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence or absence of 5 μM EGCG. Percentage activity was determined via 20S proteasome activity assay. Shown is percentage proteasome activity (mean ± SE; n ≥ 3), where activity in the absence of drug was set to 100%.

EGCG prevents proteasome inhibition and ER stress induction when combined with BZM and MG-262, but not MG-132. (A) LN229 cells were cultured for 30 hours with 20 nM BZM, 1.5 μM MG-132, or 20 nM MG-262 in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG. (Top) Percentage proteasome activity in total cell lysates was determined via 20S proteasome activity assay. (Bottom) The relative amount of polyubiquitinated proteins and the ER stress marker GRP78 was determined via Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against ubiquitin and GRP78, respectively. Western blot to actin was used as a loading control. (B) RPMI/8226 cells were cultured for 30 hours with 20 nM BZM in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG. (Top) Percentage proteasome activity from total cell lysates was determined via 20S proteasome activity assay. (Bottom) The relative amount of polyubiquitinated proteins, activated caspase-7 (cleaved casp-7), and cleavage of poly (ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP, which indicates ongoing apoptosis) in RPMI/8226 cells was determined via Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against ubiquitin, caspase-7, and PARP, respectively. (C) Highly purified proteasomes were treated with increasing concentrations of BZM in the presence or absence of 5 μM EGCG. Percentage activity was determined via 20S proteasome activity assay. Shown is percentage proteasome activity (mean ± SE; n ≥ 3), where activity in the absence of drug was set to 100%.

EGCG and BZM were also added to highly purified 20S proteasomes in the absence of any other cellular components, such as signaling proteins or organelles. Under these strictly defined conditions as well, the proteasome inhibitory activity of BZM was diminished when EGCG was present (Figure 5C), although the antagonism seemed less pronounced compared with conditions where intact cells were treated with these compounds (Figures 1,Figure 2,Figure 3–4,5A,B). Nonetheless, this result indicates that EGCG is able to inhibit BZM function in the absence of additional cellular components.

Various proteasome inhibitors and tGCG drug combinations were investigated for any consequences on ER stress and subsequent apoptosis. Expression levels of GRP78 protein represent a widely used marker for the induction of ER stress.25 As shown in Figure 5A bottom panel, this marker was strongly induced by all 3 proteasome inhibitors, and the presence of EGCG effectively prevented this induction in the case of BZM and MG-262, but not in the case of MG-132. Caspase-7 is an ER stress–associated enzyme and important mediator of ER stress–induced apoptosis.24 As shown in Figure 5B bottom panel, caspase-7 is effectively activated by BZM; similarly, BZM causes cleavage of PARP (poly (ADP ribose) polymerase), which represents one of the final steps of the proteolytic caspase cascade and reliably indicates ongoing apoptosis.37 However, in the presence of EGCG, BZM is unable to trigger caspase-7 activation or PARP cleavage, indicating that these proapoptotic events are not set in motion when the polyphenol is present.

EGCG neutralizes the antitumoral effects of BZM in vivo

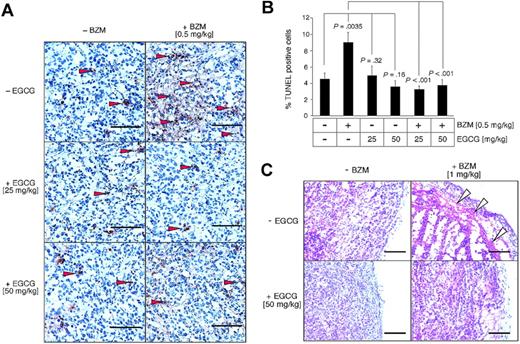

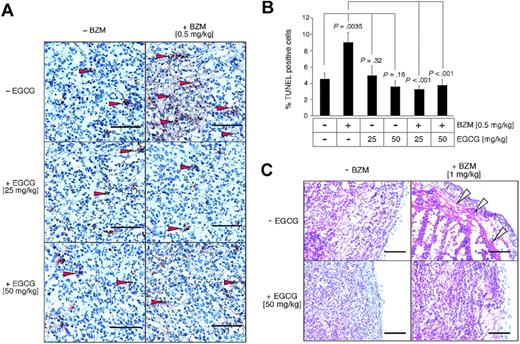

We next investigated whether the antagonistic effects of EGCG and BZM would have in vivo relevance. For this purpose, RPMI/8226 multiple myeloma cells were implanted subcutaneously into nude mice and, after sizable tumors had formed, the animals received treatment with BZM or EGCG, alone and in combination. Three days later, the animals were killed and the tumors were analyzed by TUNEL or hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining to visualize the extent of apoptotic and necrotic cell death, respectively.

We found that treatment with BZM alone (0.5 mg/kg) doubled the number of TUNEL-positive cells, that is, there was a statistically significant increase in apoptosis. However, in tumors from animals treated with EGCG alone (25 or 50 mg/kg) or with EGCG plus BZM, there was no increase of apoptotic cell death compared with tumors from nontreated controls (Figure 6A,B). In a repetition of this in vivo experiment, we doubled the dosage of BZM to 1 mg/kg and performed H&E staining to reveal any necrosis within the tumor tissue. As shown in Figure 6C, BZM-treated animals showed signs of extensive subcapsular necrosis in their tumor tissue, whereas none of the nontreated animals, EGCG-treated animals, or EGCG/BZM combination–treated animals displayed this outcome. Thus, the severe antagonistic effect of EGCG toward the cytotoxic efficacy of BZM is not merely an in vitro phenomenon, but also takes place in tumor tissues of drug-treated animals in vivo.

EGCG neutralizes the antitumoral effects of BZM in multiple myeloma in vivo. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with bortezomib and EGCG individually or in combination, or remained untreated. Seventy-two hours later, the animals were killed and the tumors were analyzed by TUNEL (apoptosis indicator) or H&E (morphology). (A) Representative microphotographic images were taken of the TUNEL staining (original magnification 400× for all panels). Arrowheads indicate representatively selected TUNEL-positive cells. (B) The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells (reddish-brown stain) was determined in 10 randomly chosen microscopic fields from each treatment group. Columns represent mean; bars, SEM. Statistically significant differences in the extent of tumor cell death between individual and combination drug treatments are indicated in the chart. (C) Representative microphotographic images were taken of the H&E staining (original magnification ×200 for all panels). Open arrowheads indicate area of subcapsular necrosis.

EGCG neutralizes the antitumoral effects of BZM in multiple myeloma in vivo. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with bortezomib and EGCG individually or in combination, or remained untreated. Seventy-two hours later, the animals were killed and the tumors were analyzed by TUNEL (apoptosis indicator) or H&E (morphology). (A) Representative microphotographic images were taken of the TUNEL staining (original magnification 400× for all panels). Arrowheads indicate representatively selected TUNEL-positive cells. (B) The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells (reddish-brown stain) was determined in 10 randomly chosen microscopic fields from each treatment group. Columns represent mean; bars, SEM. Statistically significant differences in the extent of tumor cell death between individual and combination drug treatments are indicated in the chart. (C) Representative microphotographic images were taken of the H&E staining (original magnification ×200 for all panels). Open arrowheads indicate area of subcapsular necrosis.

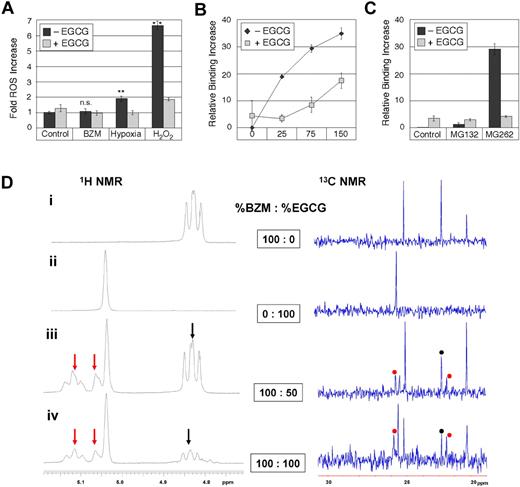

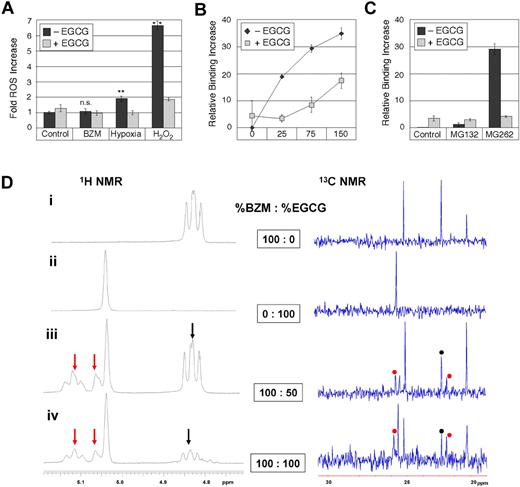

EGCG inactivates BZM via a direct reaction with its boronic acid group

As EGCG is known to have antioxidant function, we investigated whether this feature might contribute to the observed antagonism between EGCG and BZM. However, as shown in Figure 7A, BZM treatment did not generate increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and therefore, there was no basis for EGCG interference. As a positive control, cells were challenged with hypoxia (a known inducer of ROS38 ) or with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and in these cases, significantly (P = .005) increased levels of ROS were generated, which were effectively squelched by EGCG, confirming its potent antioxidant function. Taken together, these results indicated that EGCG's antioxidant function did not play a major role in its severe antagonism of BZM.

BZM does not generate ROS, but directly reacts with EGCG to form a new boronate product. (A) RPMI/8226 cells were treated with 20 nM BZM, 5 mM H2O2, or exposed to hypoxia for 18 hours in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG. Shown is the fold increase of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (mean ± SE; n ≥ 3) from 1 representative experiment; ** indicates statistically significant (P = .005) differences between hypoxia-treated or H2O2-treated cells versus untreated (control) cells; ns, not statistically significantly different from untreated control. The entire experiment was repeated in different variations and with different incubation times; yet, BZM consistently failed to increase the levels of ROS. The generation of intracellular ROS was measured via labeling with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry.23 In some of the repetitions, total ROS production was determined by ultraviolet spectrometry after incubating cells with H2DCFDA. (B) The direct binding of EGCG to BZM was investigated with the alizarin red S (ARS) reporter assay. In the absence of EGCG, there is increasing binding between ARS and rising (0-150 μM) concentrations of BZM. However, the addition of EGCG (250 μM) effectively reduces this interaction via direct competitive binding of EGCG to BZM. (C) Results from the ARS assay with MG-132 (65 μM) and MG-262 (65 μM) in the presence or absence of EGCG (250 μM). Note that MG-132 does not bind to ARS and there is no interference by EGCG, but that MG-262 strongly binds to ARS and this binding is effectively prevented by EGCG. All results are presented as mean ± SD (arbitrary units) of relative binding increase. These measurements were also repeated with TEAVIGO-EGCG and yielded very similar outcomes. (D) 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz; left) and 13C NMR spectra (100 MHz; right) of combinations of BZM and EGCG in 20% D2O in CD3CN. (i) Pure BZM, (ii) pure EGCG, (iii) a 2:1 mixture of BZM and EGCG, and (iv) a 1:1 mixture of BZM and EGCG. Selected peaks from the NMR spectra indicate the presence of the new adduct from the reaction of a 1,2-diol unit of EGCG with the boronic acid group of BZM. By increasing the amount of EGCG relative to BZM, from 2:1 in panel iii to 1:1 in panel iv, the product peaks (red arrows in the 1H NMR and red dots in the 13C NMR) increase relative to the BZM peaks (black arrows in the 1H NMR and black dots in the 13C NMR).

BZM does not generate ROS, but directly reacts with EGCG to form a new boronate product. (A) RPMI/8226 cells were treated with 20 nM BZM, 5 mM H2O2, or exposed to hypoxia for 18 hours in the presence or absence of 20 μM EGCG. Shown is the fold increase of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (mean ± SE; n ≥ 3) from 1 representative experiment; ** indicates statistically significant (P = .005) differences between hypoxia-treated or H2O2-treated cells versus untreated (control) cells; ns, not statistically significantly different from untreated control. The entire experiment was repeated in different variations and with different incubation times; yet, BZM consistently failed to increase the levels of ROS. The generation of intracellular ROS was measured via labeling with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry.23 In some of the repetitions, total ROS production was determined by ultraviolet spectrometry after incubating cells with H2DCFDA. (B) The direct binding of EGCG to BZM was investigated with the alizarin red S (ARS) reporter assay. In the absence of EGCG, there is increasing binding between ARS and rising (0-150 μM) concentrations of BZM. However, the addition of EGCG (250 μM) effectively reduces this interaction via direct competitive binding of EGCG to BZM. (C) Results from the ARS assay with MG-132 (65 μM) and MG-262 (65 μM) in the presence or absence of EGCG (250 μM). Note that MG-132 does not bind to ARS and there is no interference by EGCG, but that MG-262 strongly binds to ARS and this binding is effectively prevented by EGCG. All results are presented as mean ± SD (arbitrary units) of relative binding increase. These measurements were also repeated with TEAVIGO-EGCG and yielded very similar outcomes. (D) 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz; left) and 13C NMR spectra (100 MHz; right) of combinations of BZM and EGCG in 20% D2O in CD3CN. (i) Pure BZM, (ii) pure EGCG, (iii) a 2:1 mixture of BZM and EGCG, and (iv) a 1:1 mixture of BZM and EGCG. Selected peaks from the NMR spectra indicate the presence of the new adduct from the reaction of a 1,2-diol unit of EGCG with the boronic acid group of BZM. By increasing the amount of EGCG relative to BZM, from 2:1 in panel iii to 1:1 in panel iv, the product peaks (red arrows in the 1H NMR and red dots in the 13C NMR) increase relative to the BZM peaks (black arrows in the 1H NMR and black dots in the 13C NMR).

As an alternative, and because all of the investigated molecular and cellular effects of BZM were completely blocked in the presence of EGCG, we considered the possibility that EGCG prevented BZM function via direct interactions between the 2 molecules, which might prohibit BZM from binding to its target, the proteasome. This hypothesis is well supported by long-known findings in the field of boron chemistry: namely that boronic acid derivatives form covalent bonds with compounds having a 1,2-benzene diol moiety, resulting in the formation of cyclic boronate esters and representing one of the strongest single-pair reversible functional group interactions.39,40 In this regard, it should be noted that EGCG, ECG, EGC, and EC harbor such 1,2-benzene diol moieties (see chemical structures in Figures 1A,3A).

To investigate the postulated binding between BZM and EGCG, both compounds were added to alizarin red S (ARS), a widely used reporter system to study the interaction between boronic acids and molecules with 1,2-diols.30 As shown in Figure 7B, BZM readily bound to ARS, but this interaction was effectively blocked in the presence of EGCG, revealing effective competition by direct chemical binding of EGCG to BZM. To verify the reliability of the ARS system for our purposes, we also included MG-132 and MG-262 in repetitions of this experiment (Figure 7C). As expected, MG-132 (which lacks the boronic acid moiety) did not bind to ARS, and there was no effect of added EGCG. However, MG-262 (which differs from MG-132 only by the presence of a boronic acid moiety) displayed effective binding to ARS, which could be blocked by EGCG. Together, these data indicate direct chemical interactions between the EGCG molecule and boronic acid–based proteasome inhibitors.

Finally, to observe directly the interaction of EGCG with BZM, we carried out 1H NMR and 13C NMR experiments of several ratios of BZM and EGCG in aqueous media (Figure 7D). By simply mixing the 2 compounds, the direct formation of a new adduct could be observed in the NMR spectra (Figure 7Diii). Furthermore, the amount of the new adduct increased, relative to BZM, upon the increased addition of EGCG (Figure 7Div). Overall, these results demonstrate that EGCG forms a stable cyclic boronate adduct with the boronic acid moiety of BZM and, thereby, prevents BZM from acting as a proteasome inhibitor.

Discussion

Green tea, concentrated GTE, and certain individual components of green tea, such as EGCG, have widely recognized health benefits, which include purported anticarcinogenic and antitumor effects. Besides being used by healthy people as a means to support continued health, this “miracle herb” extract is also consumed by many cancer patients who follow popular trends and self-medicate with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in hopes to support their conventional therapy or to lessen the burden of side effects—sometimes without the knowledge of their health care provider. In an effort to harness the therapeutic potential of green tea in a more systematic fashion, numerous clinical trials are ongoing to establish the framework for its future therapeutic use.

GTE or EGCG may also hold cancer therapeutic potential when combined with established cancer treatments.41 In our current study presented here, we investigated whether GTE or EGCG would be able to boost the anticancer efficacy of BZM, a proteasome inhibitor that is in clinical use for the treatment of multiple myeloma and is under consideration for the treatment of other cancers as well. To our surprise, we discovered that GTE, as well as some of its individual components, effectively blocked the anticancer efficacy of BZM; that is, in the presence of polyphenolic green tea components, BZM was unable to exert proteasome inhibitory function and, as a consequence, there was no trigger for proapoptotic ER stress and subsequent cell death.

The severe antagonistic effect of EGCG appeared to require the presence of the boronic acid moiety in BZM. Among the 6 proteasome inhibitors tested, the boronic acid–containing ones (BZM, MG-262, PS-IX) were similarly incapacitated by EGCG, whereas none of those without this functional group (NFV, MG-132, PS-I) were affected by EGCG. In this context, it is noteworthy that the chemical structures of MG-262 (effective inhibition by EGCG) and MG-132 (no inhibition by EGCG) differ only in the presence/absence of the boronic acid moiety (Figure 4A), indicating that the decisive mechanism of EGCG's antagonism resides with the chemical structure of the target molecule (ie, the boronic acid moiety), not its function (ie, proteasome inhibition).

The ability of molecules with a 1,2-diol group to form covalent cyclic boronate moieties with boronic acid in a tight, but reversible manner, is a well-described and long-established chemical process, and is known to be one of the strongest single-pair reversible functional group interactions in an aqueous environment.39,40,42 In retrospect, it was therefore not surprising that we were able to verify direct molecular interactions between EGCG and the bortezomib molecule (Figure 7), although similar behavior is expected for other polyphenols that harbor 1,2-benzenediol groups, such as EGC, ECG, and EC. Interestingly, it has been reported earlier that vitamin C, a 1,2-diol–containing compound as well, is able to antagonize cell killing by BZM.43 This latter report measured the direct interaction of vitamin C with 5-DMANBA (a fluorescent model boronic acid compound) and provided evidence that the antagonism of vitamin C against BZM was based on the direct reaction with the boronic acid moiety. In addition, another very recent report showed that dietary flavonoids, such as quercetin and myricetin, underwent chemical reactions with the boronic acid group of BZM, thereby diminishing BZM's ability to trigger apoptosis in tumor cells.44 The results reported in our present study regarding the severe antagonism of EGCG toward BZM can be attributed similarly to a direct molecular interaction between the 2 molecules. This view is in agreement with our finding that proteasome inhibition by BZM does not take place in the presence of EGCG, that is, BZM is prevented from exercising the key step of its biologic activity (Figure 5).

An earlier study had reported that EGCG and ECG—but not EGC or EC—exerted protease inhibitory function.45 An earlier study had reported that EGCG and ECG—but not EGC or EC—exerted protease inhibitory function.45 However, we were unable to detect such inhibition, either indirectly via the cellular accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins by Western blot analysis (Figure 5A,B), or directly via the measurement of proteasomal chymotryptic activity (Figure 5C), and it is likely that the observed EGCG actions are due to the higher concentrations used. We note, however, that in our experiments all 4 of these polyphenols were able to antagonize the cytotoxicity of BZM (Figure 3). Therefore, there is a lack of correlation between the earlier reported proteasome inhibitory activity profile of these compounds and their currently presented antagonism toward BZM, which would argue against a major role of proteasome inhibition, if any, in the antagonistic events we are reporting. This view is supported further by our observation that the severe antagonism of EGCG appears to be dependent on the chemical structure of its targets (ie, the boronic acid moiety of the proteasome inhibitors), rather than their function (ie, EGCG does not interfere with other proteasome inhibitors lacking a boronic acid group; Figure 4).

Earlier reports34,35 had indicated that EGCG alone may have cytotoxic effects on MM cell lines when applied at concentrations of 10 μM or higher. In our own experimental setting, however, we noted only weak cytotoxic effects starting at 20 μM (while at the same time EGCG continued to exert profound antagonism toward BZM cytotoxicity; Figures 1,Figure 2–3). The absence of cytotoxic effects at 10 μM, which contrasted with the earlier studies, was noted with EGCG from 2 entirely different sources, that is, from Sigma-Aldrich and from a health food store (TEAVIGO-EGCG). We noticed, however, that during prolonged storage at room temperature, the clear EGCG stock solution acquired a brownish color (presumably due to auto-oxidation) and became somewhat more toxic to cells. This did not happen when EGCG solution was used fresh or after storage at −80°C. Similarly, there was comparatively higher cytotoxicity when GTE (purchased as a dark-brown liquid from a health food store at room temperature) was used (Figure 3), further pointing to the possibility that variable storage conditions may impact the cytotoxic potency of solutions containing EGCG and that this may contribute to the reported discrepancies concerning EGCG toxicity at 10 μM or more. In all cases, however, GTE and EGCG at low (nontoxic) as well as at higher (weakly toxic) concentrations effectively abolished BZM toxicity.

Several of the previously mentioned components (EGCG, EGC, ECG, vitamin C) are known for their potent antioxidant function. In view of several earlier reports, which provided evidence that BZM triggered the formation of ROS, it would be reasonable to conclude that antioxidants antagonize BZM cytotoxicity via their radical scavenging function, and that this would be the major antagonistic mechanism of the green tea compounds used in our study. However, several lines of evidence argue against this conclusion. (1) Some earlier conclusions about the role of ROS in BZM-induced cell death were based on the use of tiron (a sulfonate-containing 1,2-benzene diol) as an antioxidant.23,46 Although tiron is able to prevent BZM-induced cell death, it is also one of those 1,2-diol compounds that is able to directly react with the boronic acid moiety of BZM; thus, the use of tiron does not allow to distinguish between ROS scavenging and inactivation of BZM via direct binding. (2) In previous side-by-side comparisons, only those antioxidants with 1,2-diol groups (vitamin C, tiron, quercetin), but not those without (N-acetyl-cysteine, butylated hydroxyanisole, MnTBAP, glutathione, vitamin E), were able to antagonize cell killing by BZM.43,44,47,48 (3) In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells, induction of ROSs was shown to be a consequence of BZM-induced ER stress.23 In our cell system as well, markers of severe ER stress (GRP78, caspase-7) were induced by BZM; however, in the presence of EGCG, ER stress was entirely prevented (Figure 5) and therefore could not possibly serve as a source of ROSs. (4) Antioxidants with 1,2-benzene diol groups are able to antagonize BZM function even in cells where BZM treatment does not cause ROS; for example, in our cell system, treatment with BZM did not increase ROSs (Figure 7A), yet EGCG and other antioxidants (EGC, ECG) were still able to block BZM cytotoxicity; similarly, in several lung cancer cell lines, BZM did not increase ROS either, yet vitamin C or tiron was able to prevent BZM cytotoxicity.43 In summary, these considerations support our conclusion that EGCG and other components of GTE exert their antagonistic function against BZM (and other boronic acid–based proteasome inhibitors) via direct interactions between these molecules, rather than indirectly via ROS scavenging.

Compared with the previously identified antagonists of BZM,43,44,47,48 we find that the antagonism of EGCG toward BZM treatment is at least 2 orders of magnitude more potent than vitamin C or tiron; for example, whereas the latter required concentrations in the range of 500 to 1000 μM to be highly effective,43 EGCG exerts pronounced (80%-100%) protection at concentrations as low as 2.5 to 5.0 μM (Figure 1). Even more so, when applied as complete GTE, very substantial protection can be seen at EGCG concentrations of 1.0 μM—presumably because other polyphenols that are present in GTE contribute as well (Figure 3). It is noteworthy that these low concentrations are not merely diminishing the cytotoxic efficacy of BZM, but are able to completely abolish it, which is also apparent in the in vivo model we used, where significantly increased apoptosis and necrosis in tumor tissue in response to BZM therapy was entirely absent when EGCG was added (Figure 6). Furthermore, in view of the underlying mechanism of EGCG/BZM antagonism, namely chemical interactions between the molecules (Figure 7), we envision that inactivation of BZM's therapeutic efficacy may apply not only to MM, but also to any other cancer type where BZM might be considered for inclusion in the therapeutic regimen. A case in point is our finding that EGCG abolishes BZM's cytotoxic potency in glioblastoma cell lines as well (Figure 2).

In humans, EGCG concentrations of 5 to 8 μM can easily be achieved after the ingestion of capsules containing GTE (polyphenon E).33 We therefore have no doubt that our discovery is highly relevant for clinical considerations and would strongly urge patients undergoing BZM therapy to abstain from consuming green tea products, in particular those widely available, highly concentrated GTEs that are sold in liquid or capsule form. The significance of our view may be further underscored by the following consideration: Based on the proposed mechanism by which EGCG/GTE antagonizes BZM, namely via direct chemical inactivation of BZM and thereby preventing its biologic activity, one would expect that not only the therapeutic efficacy of BZM is being neutralized, but perhaps also the emergence of some of the side effects that usually accompany BZM therapy. As a consequence, patients consuming EGCG/GTE products may experience improved well being, which may encourage further increased EGCG/GTE dosages, leading to even further improvements—while at the same time, and unknowingly, the therapeutic efficacy of their BZM treatment is severely blunted, if not entirely obliterated.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Frank Furnari (Ludwig Institute of Cancer Research, La Jolla, CA) and Dr Nancy Krett (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) for the various cell lines used in this study. We thank Simon Coetzee for assisting with cell culturing.

E.B.G. wishes to dedicate this work to the memory of J.N.B.

This project was supported by funding from the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (Norwalk, CT; A.H.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: E.B.G., P.Y.L., A.K., and K.J.G. performed experiments and analyzed the results; E.B.G., T.C.C., S.G.L., N.A.P., and E.C. designed experimental approaches and provided input toward the paper; and A.H.S. directed the study and revised the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Axel H. Schönthal, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, 2011 Zonal Ave, HMR-405, Los Angeles, CA 90089-9094; e-mail: schontha@usc.edu.