Abstract

Molecular paradigms underlying the death of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) induced by ionizing radiation are poorly defined. We have examined the role of Puma (p53 up-regulated mediator of apoptosis) in apoptosis of HSCs after radiation injury. In the absence of Puma, HSCs were highly resistant to γ-radiation in a cell autonomous manner. As a result, Puma-null mice or the wild-type mice reconstituted with Puma-null bone marrow cells were strikingly able to survive for a long term after high-dose γ-radiation that normally would pose 100% lethality on wild-type animals. Interestingly, there was no increase of malignancy in the exposed animals. Such profound beneficial effects of Puma deficiency were likely associated with better maintained quiescence and more efficient DNA repair in the stem cells. This study demonstrates that Puma is a unique mediator in radiation-induced death of HSCs. Puma may be a potential target for developing an effective treatment aimed to protect HSCs from lethal radiation.

Introduction

Hematopoietic cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs), are sensitive to ionizing radiation. Total body γ-irradiation (TBI) with 5 to 10 Gy doses results in an acute radiation syndrome with possible lethality primarily due to hematopoietic failure.1 Patients receiving radiation therapy may develop acute bone marrow (BM) injury as the consequence of induced apoptosis in HSCs and HPCs. In addition, γ-radiation causes long-term bone marrow damage via induction of HSC senescence.2 Understanding the molecular mechanisms of γ-radiation–induced HSC apoptosis and/or senescence may provide potential targets for developing an effective treatment to ameliorate radiation-induced BM injury.

The p53 signaling is a critical pathway that responds to ionizing radiation by regulating multiple cellular processes, such as proliferation and DNA repair and survival.3 Inhibiting p53 may have a radioprotective effect through the prevention of p53-mediated apoptosis in selective tissues.4,5 However, p53 deficiency only transiently protects the hematopoietic system,6 and actually sensitizes the gastrointestinal system to damage after radiation exposure.7 Moreover, because p53 controls the expression and function of numerous downstream target genes, targeting p53 causes deleterious effects in addition to radioprotection8,9 and increases risk for tumor formation.10 Therefore, targeting downstream mediators of the p53 pathway without directly interfering with p53 itself would be a more desirable approach to provide long-term survival of exposed persons. Although p21 is up-regulated by p53, ablation of p21 does not confer radioprotection.7 In fact, p21 deficiency could even have a negative effect on murine stem cells because it could cause premature exhaustion of HSCs during serial BM transplantation (BMT), 5-fluorouracil treatments,11,12 or radiation exposure.13 A specific downstream target in the p53 pathway for radioprotection in HSCs has yet to be identified.

Puma (p53 up-regulated mediator of apoptosis, also called Bbc3) is a direct p53 target gene that encodes a BH3-only proapoptotic protein.14,15 Puma appears to be essential for hematopoietic cell death triggered by ionizing radiation, deregulated c-Myc expression, and cytokine withdrawal.16,17 It has been reported that lymphoid cells are resistant to γ-irradiation in the absence of Puma.18 Wu et al reported that activation of Slug, a transcriptional repressor induced by p53 upon irradiation, protects the HPCs from apoptosis by repressing transcription of Puma.19 A significant role for Puma in the apoptosis of mouse intestine progenitor cells has also been recently documented.20 However, it has not yet been defined whether Puma plays a definitive role in HSCs, or whether targeting Puma in HSCs as well as HPCs is beneficial for the long-term survival of a whole organism.

In this study, we have investigated the role of Puma in HSC survival upon radiation injury. Our results demonstrate for the first time an essential role for Puma in the apoptosis of HSCs upon radiation exposure, and that inhibition of Puma in HSCs provides a profound benefit for the long-term survival of the mice, without an increased risk of malignancies after irradiation. This effect was associated with better preservation of the quiescent state of HSCs. Moreover, Puma−/− HSCs likely permitted more efficient DNA repair after radiation exposure. These results have important implications for therapeutic targeting of Puma in radioprotection and offer new insights into p53 downstream signaling in potential leukemogenesis.

Methods

Mice

All mice were in a C57BL/6 (CD45.2) background or the congenic B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/Boy (CD45.1) background. In the experiments of competitive BMT, the first generation (F1) of C57BL/6 and B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/Boy (CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygote) mice were generated and used for competitor cells because the hematopoietic cells generated from the F1 mouse can be easily separated from donor cells or residual recipient cells by flow cytometry after transplantation. All procedures and animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at University of Pittsburgh.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

Blood was drawn from the tail vein at different time points after BMT and stained with anti–CD3-phycoerythrin, anti–Gr-1-phycoerythrin-cyanin 7, anti–Mac-1-allophycocyanin, anti–B220-phycoerythrin-Texas Red, anti–CD45.1-phycoerythrin–cyanin 5.5, and anti–CD45.2-fluorescein isothiocyanate (eBioscience). After staining, red blood cells were lysed by BD FACs lysing solution (BD Biosciences), and then analyzed on a cyan flow cytometer (DakoCytomation). For stem cell enrichment and staining, bone marrow nuclear cells (BMNCs) were isolated from age- and sex-matched Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice. BMNCs were stained with anti–mouse c-Kit microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The c-Kit–enriched cells were then stained with a mixture of phycoerythrin-cyanin 7–conjugated antibodies against multilineage (including CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, Gr-1, Mac-1, and TER-119), anti–Sca-1-phycoerythrin, anti–c-Kit-allophycocyanin, anti–CD34-fluorescein isothiocyanate (eBioscience). After staining, single CD34−Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ (LKS) long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) were sorted for in vivo and in vitro studies.

Bone marrow transplantation in mice

All the experimental design and procedures for BMT in mice were summarized in supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Briefly, female recipients were irradiated at 10 Gy at the rate of 0.84 Gy min−1 (Cesium 137, Model MKL-68 IRRAD; JL Shepherd & Associates) the day before transplantation. BMNCs or sorted HSCs were injected into recipients through the tail vein on the following day. Detailed information of the transplantation strategy is described in supplemental Figure 1.

Real-time RT-PCR

Different subsets of HSCs and HPCs were sorted into culture medium. An equal number of cells were distributed into different microtubes for exposure to different doses of radiation (0, 2, 4, and 8 Gy). After irradiation, all cells were incubated for 2 hours in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Then cells were spun down and resuspended in lysis buffer for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted with the RNA Nanoprep Kit (Strategene) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription (RT) was achieved by using oligo(dT)12-18 and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out with the Chromo 4 Detector System (Bio-Rad) by mixing DyNAmo SYBR Green Master Mix (Finnzymes), 0.3 μM of specific forward and reverse primers, and diluted cDNA. The parameters for the thermal cycling of PCR were 1 seconds at 95°C and 60 seconds at 60°C. The PCR primers used in the experiment are as follows: β-actin-GGA ATC GTG CGT GAC ATC AAA G (forward) and TGT AGT TTC ATG GAT GCC ACA G (reverse); Puma-AGC AGC ACT TA AGT CGC C (forward) and CCT GGG TAA GGG GAG GAG T (reverse).

TUNEL assay

The terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase–mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was carried out by using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR Red (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The number of apoptotic cells was calculated as the ratio of TUNEL-positive (red) cells versus total 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole–positive (blue) cells.

Cell-cycle analysis

G0 versus G1 fraction in cell cycle was measured with Hoechst 3334 and Pronin Y staining according to the method described by Shen et al.21

Immunofluorescence cytochemistry

LKS cells were collected and spun onto slides. Samples were fixed and permeabilized with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively. Cells were incubated with diluted antibodies in 0.5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline in humidified chamber for 1 hour in room temperature. The cells were stained with anti-phosphorylated histone γ-H2AX antibody (Trevigen) and Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes). Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was stained with tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate–conjugated anti–mouse PCNA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole or Draq5 (Biostatus) was used as nuclear staining. Slides were observed and photographed under a confocal fluorescence microscope (Fluoview 1000; Olympus).

Statistical analysis

Average values were compared using the Student 2-tailed t test for independent or paired means. Comparisons between proportions were done using the Fisher exact test or the χ2 test as specified in the Figure 5A legend. A value of P less than .05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

A minimal impact of Puma on HSCs under homeostasis

To determine the potential effect of Puma on HSCs by radiation, we first examined Puma mRNA expression in HSCs and HPCs before and after γ-irradiation exposure using real-time PCR. Different subsets of HSCs and HPCs were sorted out separately based on phenotypic markers of hematopoietic lineages, c-Kit, Sca-1 plus CD34, and applied for real-time RT-PCR.22-25 Basal expression of Puma was very low with 1% to 3% of the level of β-actin expression in most types of immature hematopoietic cells (Figure 1A), including CD34−LKS repopulating LT-HSCs, CD34+ LKS short-term repopulating HSCs (ST-HSCs) and the downstream progenitor cells. Notably, Puma expression was slightly higher in megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors. However, when the isolated HSCs and HPCs were exposed to radiation in vitro, Puma was significantly up-regulated 2 hours after irradiation in a dose-dependent manner in LT-HSCs (Figure 1B), as well as ST-HSCs and downstream HPCs (supplemental Figure 2). This result indicates that Puma expression is tightly controlled in HSCs under steady-state conditions and can be rapidly up-regulated in response to radiation stress.

Transcriptional expression of Puma in HSCs and HPCs. (A) Basal expression of Puma mRNA in different hematopoietic cell subsets under homeostatic conditions. The different subsets of hematopoietic cells were sorted for real-time RT-PCR analysis to quantify the levels of gene expression. LT-HSC (CD34−LKS); ST-HSC (CD34+LKS); CMP, common myeloid progenitor (CD34+FcγRlowCD127−LKS−); MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors (CD34−FcγRlowCD127−LKS−); CLP, common lymphoid progenitor (CD127+L−KlowSlow); GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (CD34+FcγRhiCD127−LKS−). The values on y-axis indicate the fold change normalized to β-actin. (B) Induced expression of Puma mRNA in LT-HSCs after irradiation. Each bar shows the mean ± SD from 3 replicates. *P < .05.

Transcriptional expression of Puma in HSCs and HPCs. (A) Basal expression of Puma mRNA in different hematopoietic cell subsets under homeostatic conditions. The different subsets of hematopoietic cells were sorted for real-time RT-PCR analysis to quantify the levels of gene expression. LT-HSC (CD34−LKS); ST-HSC (CD34+LKS); CMP, common myeloid progenitor (CD34+FcγRlowCD127−LKS−); MEP, megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors (CD34−FcγRlowCD127−LKS−); CLP, common lymphoid progenitor (CD127+L−KlowSlow); GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (CD34+FcγRhiCD127−LKS−). The values on y-axis indicate the fold change normalized to β-actin. (B) Induced expression of Puma mRNA in LT-HSCs after irradiation. Each bar shows the mean ± SD from 3 replicates. *P < .05.

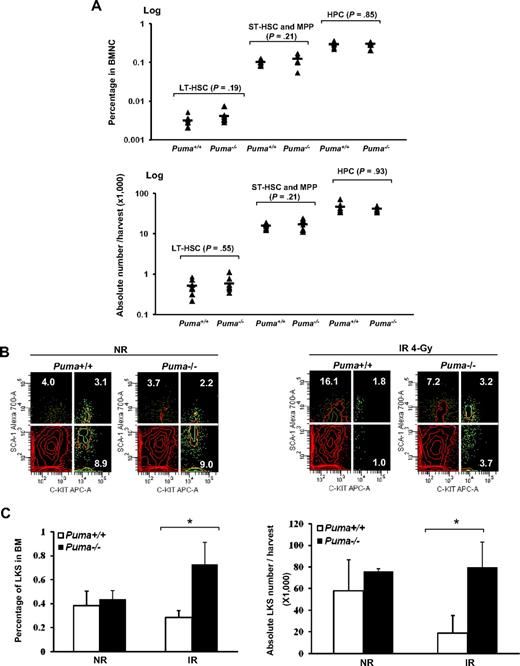

The low expression of Puma in HSCs and HPCs before irradiation suggests that the role of Puma in HSCs and HPCs under normal conditions may be limited. To support this point, we further examined the frequency of HSCs and HPCs in the bone marrow of Puma−/− mice compared with wild-type control mice by flow cytometric analysis. As shown in Figure 2A, there was no significant difference in either frequency or absolute number of LT-HSCs (CD34−LKS), ST-HSCs plus multipotent progenitors (CD34+LKS), and HPCs (LKS−) between Puma+/+ and Puma−/− animals. We also examined the in vitro differentiation potential of LT-HSCs with a single stem cell culture assay.26 Again, there was no significant difference between Puma+/+ and Puma−/− groups in either the total colony yield or the percentage of multilineage colonies (supplemental Figure 3), confirming that Puma has no significant effect on the differentiation potential of HSCs under normal homeostasis.

Quantitative measurements of HSCs and HPCs with or without 4-Gy irradiation. (A) Quantitative analysis of the frequencies of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs plus multipotent progenitors (CD34+LKS) and HPCs (LKS−) in the Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice without irradiation by flow cytometry. The percentage of each cell population (top) was calculated by the acquired number of the each population divided by the acquired number of CD45+ nucleated cells. The absolute number per harvest (bottom) was calculated by percentage of the cells multiplied by the number of BMNCs. The Student t test was used for the statistical analysis between groups (n = 7). (B) Relative increase of LKS cells after TBI in the absence of Puma. The Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice (n = 3 in each phenotype) were subjected to 4-Gy irradiation (IR). LKS cells were measured in the bone marrow of the mice 6 hours after radiation in comparison with the nonirradiated (NR) controls (n = 3 in each phenotype). Representative profiles in flow cytometry from NR (left) and IR (right) groups were shown. (C) The percentage of LKS cells in the bone marrow (left) and the absolute number per harvest (right) with and without radiation were summarized (*P < .05).

Quantitative measurements of HSCs and HPCs with or without 4-Gy irradiation. (A) Quantitative analysis of the frequencies of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs plus multipotent progenitors (CD34+LKS) and HPCs (LKS−) in the Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice without irradiation by flow cytometry. The percentage of each cell population (top) was calculated by the acquired number of the each population divided by the acquired number of CD45+ nucleated cells. The absolute number per harvest (bottom) was calculated by percentage of the cells multiplied by the number of BMNCs. The Student t test was used for the statistical analysis between groups (n = 7). (B) Relative increase of LKS cells after TBI in the absence of Puma. The Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice (n = 3 in each phenotype) were subjected to 4-Gy irradiation (IR). LKS cells were measured in the bone marrow of the mice 6 hours after radiation in comparison with the nonirradiated (NR) controls (n = 3 in each phenotype). Representative profiles in flow cytometry from NR (left) and IR (right) groups were shown. (C) The percentage of LKS cells in the bone marrow (left) and the absolute number per harvest (right) with and without radiation were summarized (*P < .05).

Radioprotective effect of Puma loss on HSCs in vivo

To determine whether Puma loss confers a protective advantage of HSCs to γ-irradiation in vivo, we exposed Puma−/− and Puma+/+ mice to sublethal radiation (4 Gy) and analyzed the levels of LKS cells in the bone marrow. As shown in Figure 2B and C, without radiation, the percentage or total number of LKS cells in both Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice were comparable without significant difference. However, when the mice were exposed to 4-Gy irradiation, LKS cells decreased significantly in Puma+/+ bone marrow 6 hours after radiation. By contrast, abundance of LKS cells in Puma−/− mice was very close to those of nonradiated Puma+/+ or Puma−/− mice. Similar results were observed when the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule markers (CD150 and CD48) were applied for the phenotypic analysis (supplemental Figure 4).27

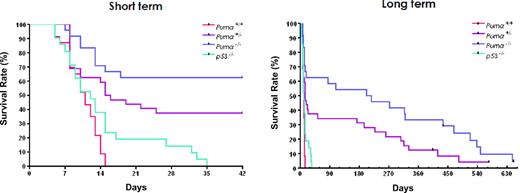

To test whether Puma loss has radioprotective effect in lethal γ-radiation, we challenged Puma+/+, Puma+/−, Puma−/−, and p53−/− mice with 10 Gy TBI and monitored the survival of these mice for a period of nearly 2 years (Figure 3). As expected, the Puma+/+ mice died quickly after irradiation with median survival of 10.5 days. Surprisingly, Puma−/− mice survived much longer with the median survival of 215 days (Puma−/− vs Puma+/+, P < .01). A dose effect was observed in the Puma+/− mice, because loss of one Puma allele significantly prolonged the survival (Puma+/− vs Puma+/+, P < .01; Puma−/− vs Puma+/−, P < .05). By contrast, p53−/− mice were more sensitive than Puma−/− or Puma+/− mice to 10-Gy irradiation and all p53−/− mice died within 35 days after radiation (Puma−/− or Puma+/− vs p53−/−, P < .01), likely due to gastrointestinal syndrome,7 resulting in increased bacterial infections.28 The Puma−/− and Puma+/− mice that survived the initial 30 days typically developed arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, epicarditis, and myocarditis. Among 32 irradiated Puma+/− and 24 Puma−/− mice, only 2 mice developed B-cell lymphoma at 11 and 7 mo, respectively. The incidence of tumors in irradiated Puma−/− and Puma+/− mice was comparable with nonradiated mice with C57BL/6 background (information is available on The Jackson Laboratory Web site), indicating that Puma−/− deficiency does not increase the tendency of tumor development after irradiation.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in Puma+/+, Puma+/−, Puma−/−, and p53−/− mice challenged with 10 Gy of γ-irradiation. The plots of short-term analysis (42 days, top) and long-term analysis (more than 600 days, bottom) were shown, respectively. All the Puma+/+ (n = 23, red) and p53−/− (n = 21, green) mice died within 35 days and there was no significant difference between these 2 groups (P = .07). The Puma−/− (n = 24, blue) and Puma+/− (n = 32, purple) mice survived much longer. There are significant differences when Puma−/− or Puma+/− groups were compared with Puma+/+ or p53−/− groups (P < .01in all groups).

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in Puma+/+, Puma+/−, Puma−/−, and p53−/− mice challenged with 10 Gy of γ-irradiation. The plots of short-term analysis (42 days, top) and long-term analysis (more than 600 days, bottom) were shown, respectively. All the Puma+/+ (n = 23, red) and p53−/− (n = 21, green) mice died within 35 days and there was no significant difference between these 2 groups (P = .07). The Puma−/− (n = 24, blue) and Puma+/− (n = 32, purple) mice survived much longer. There are significant differences when Puma−/− or Puma+/− groups were compared with Puma+/+ or p53−/− groups (P < .01in all groups).

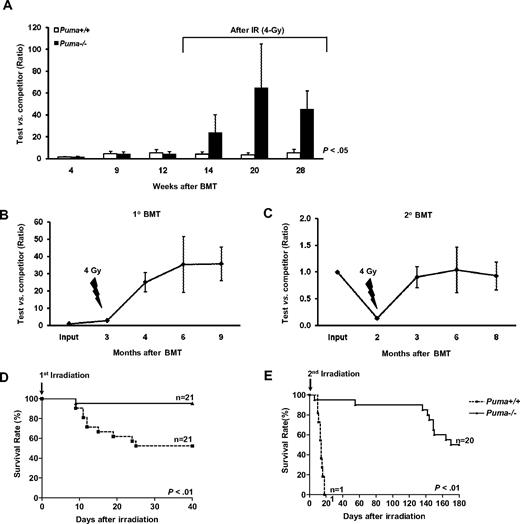

Resistance of reconstituted HSCs to radiation damage in vivo in the absence of Puma

Resistance of HSCs to radiation damage in Puma−/− mice may be due to intrinsic effects of Puma deficiency within HSCs or due to protective effects from the environment in the whole organism. To address this question, we established a competitive transplantation mouse model (supplemental Figure 1A). One hundred CD34−LKS cells from either Puma+/+ or Puma−/− mice were transplanted into lethal radiated congenic mouse recipients along with 1.5 × 105 competitive BMNCs from a F1(CD45.1 × CD45.2) mouse. As shown in Figure 4A, the engraftment levels of donor LT-HSCs versus competitor BMNCs were approximately 4∼6:1 in both Puma+/+ and Puma−/− groups. Then the reconstituted mice were exposed to sublethal irradiation (4 Gy) 12 weeks after transplantation. In a Puma−/− group, remarkably, the Puma−/− donor cells became dominant in the recipients after 4-Gy irradiation. The ratio of Puma−/− cells to competitor cells altered from 4∼6:1 to 24:1 in 2 weeks and reached to 45:1 14 weeks after 4-Gy irradiation, whereas the ratio of Puma+/+ cells to competitor cells remained 4∼6:1. Multilineage analysis showed that the percentages of T, B, and myeloid lineages were similar between the 2 groups (supplemental Figure 5), indicating that there is no outgrowth of specific lineages in a Puma−/− HSC transplanted group after radiation. Furthermore, we calculated the absolute number of LT-HSCs derived from the original 100 LT-HSCs transplanted into the recipients 6 months after transplantation. The CD34−LKS cells in Puma−/− group increased 53-fold (5320/100), whereas those in Puma+/+ group only increased about 7.5-fold (757/100). In other words, there were 7 times more donor-derived LT-HSCs in the recipients of Puma−/− HSCs than in the recipients of Puma+/+ HSCs after irradiation (Table 1). Thus, γ-irradiation significantly targeted Puma−/− HSCs, whereas Puma−/− HSCs were able to survive 4-Gy radiation insult.

Radiation resistance of engrafted hematopoietic stem cells in the absence of Puma. (A) Radioprotection of HSCs by deletion of Puma in competitive transplantation model. The experimental design was shown in detail in supplemental Figure 1A. The hematopoietic contribution in blood by 100 LT-HSCs before and after 4-Gy irradiation was indicated by the ratios of CD45.2 to CD45.1/.2 cells (n = 4 in both Puma+/+ and Puma−/− groups). (B-C) Self-renewing capacities of Puma−/− HSCs remained after serial competitive transplantation and 4-Gy radiation. The experimental design was shown in detail in supplemental Figure 1B. The engraftment levels of Puma−/− HSCs relative to competitor cells in primary recipients (B) and secondary recipients (C) were shown, respectively. (D-E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival of the mice reconstituted with Puma+/+ or Puma−/− hematopoietic cells (supplemental Figure 1C) exposed to first round 9-Gy irradiation (D) and second round 9-Gy irradiation (E). P values are indicated in the graphs.

Radiation resistance of engrafted hematopoietic stem cells in the absence of Puma. (A) Radioprotection of HSCs by deletion of Puma in competitive transplantation model. The experimental design was shown in detail in supplemental Figure 1A. The hematopoietic contribution in blood by 100 LT-HSCs before and after 4-Gy irradiation was indicated by the ratios of CD45.2 to CD45.1/.2 cells (n = 4 in both Puma+/+ and Puma−/− groups). (B-C) Self-renewing capacities of Puma−/− HSCs remained after serial competitive transplantation and 4-Gy radiation. The experimental design was shown in detail in supplemental Figure 1B. The engraftment levels of Puma−/− HSCs relative to competitor cells in primary recipients (B) and secondary recipients (C) were shown, respectively. (D-E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival of the mice reconstituted with Puma+/+ or Puma−/− hematopoietic cells (supplemental Figure 1C) exposed to first round 9-Gy irradiation (D) and second round 9-Gy irradiation (E). P values are indicated in the graphs.

To gauge whether Puma loss can protect self-renewing capabilities of HSCs from radiation injury, we conducted serial competitive BMT and challenged the recipients with 4-Gy radiation sequentially (supplemental Figure 1B). In short, equal numbers of bone marrow cells from Puma−/− and Puma+/+ mice were mixed together and transplanted into lethally radiated recipient mice. As expected, the Puma−/− hematopoietic cells did not show a growth advantage to Puma+/+ hematopoietic cells in same recipients after transplantation (Figure 4B). When the recipient mice were challenged with 4-Gy radiation, the portion of Puma+/+ cells progressively eradicated, whereas the Puma−/− cells became more than 95% dominant 6 months after 4-Gy radiation. Then the BMNCs isolated from these primary recipient mice were mixed with equal numbers of competitor bone marrow cells from unmanipulated wild-type mice and retransplanted into secondary recipients. As shown in Figure 4C, the percentage of Puma−/− hematopoietic cells in the secondary recipients dropped from 50% to 14% 2 months after transplantation. Based on the finding decades ago,29 transplantation itself would decrease self-renewing ability of HSCs by at least 90% in general.29,30 The fact that the reconstituting ability of transplanted 4-Gy irradiated Puma−/− HSCs was similar to that of transplanted, but nonirradiated, Puma+/+ HSCs indicates that the functionality of the transplanted Puma−/− HSC population was not compromised after the first round of 4-Gy radiation. More strikingly, when the secondary recipients were exposed to 4-Gy radiation again, this transplantation-induced disadvantage of primarily transplanted and 4-Gy–irradiated Puma−/− HSCs was completely reversed in the secondary recipients 6 months after secondary 4-Gy irradiation. Phenotypic analysis of HSCs using LKS or SLAM markers further confirmed that Puma−/− HSCs were reserved in the secondary recipients (supplemental Figure 6). Thus, Puma−/− HSCs are able to resist the second round of radiation, indicating that the potential of self-renewal and differentiation of Puma−/− HSCs remained intact after multiple rounds of irradiation.

Given the strong radioprotective effect of Puma deficiency on HSCs in vivo as described in this study and on HPCs by other studies,16,17,19 we also attempted to determine the beneficial effects of Puma deletion exclusively within the hematopoietic system on overall long-term recipient survival following lethal irradiation. To this end, we reconstituted lethally irradiated wild-type mice with Puma+/+ or Puma−/− BMNCs. At 3 months after transplantation, fully engrafted recipients were subjected to 2 rounds of 9-Gy TBI (supplemental Figure 1C). As shown in Figure 4D, 10 of 21 Puma+/+ recipients died within 40 days, but only 1 of 21 mice in the Puma−/− group died (P < .01). After second rounds of irradiation on survived animals, all (100%) of the remaining mice in the Puma+/+ group died within 16 days, whereas 18 of 20 mice in the Puma−/− group survived (Figure 4E). Moreover, similar to Puma−/−-null mice, Puma−/−-reconstituted animals did not raise the tendency of leukemia or lymphoma development. Rather, the death of the few Puma−/−-reconstituted mice was mainly attributable to chronic radiation damage to nonhematopoietic organs as indicated by pulmonary fibrosis (data not shown), a known phenomenon induced by TBI as previously shown by others.31

Taken together, these phenotypic and functional assessments involving the transplantation models demonstrated that a strong radioprotection of HSCs conferred by Puma deficiency in HSCs is autonomous.

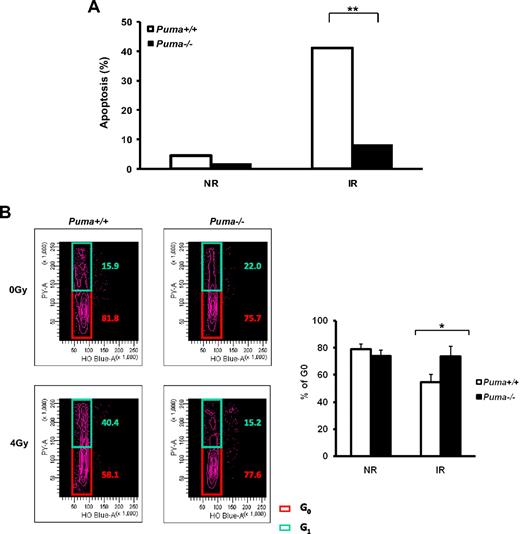

Decreased apoptosis and remained quiescence of HSCs in the absence of Puma

To investigate the cellular mechanisms of radioprotection effect due to Puma deficiency in HSCs, we performed several assessments in vitro. We first validated the anti-apoptotic effect of Puma loss on the viability of HSCs by the TUNEL assay (Figure 5A). Nearly 50% of Puma+/+ LKS cells underwent apoptosis 24 hours after 4-Gy irradiation. By contrast, most Puma−/− LKS cells remained alive in vitro after radiation. These data suggest that Puma is largely responsible for the apoptotic effect downstream of p53 in HSCs after irradiation, which is in agreement with previous observations in other cell types, including some tissue progenitor cells.20,32 Furthermore, previous studies have shown that the quiescence of HSCs serves as a critical cellular defense mechanism by which HSCs can be protected from various damaging stress conditions, such as radiation.11,33 Thus, we examined the cell-cycle status of HSCs in the absence of Puma before and after radiation. As shown in Figure 5B, a significant fraction of viable cells in the G0 phase of cell cycle was maintained in the irradiated Puma−/− LKS cells 20 hours after irradiation. In contrast, the G0 fraction was significantly reduced in Puma+/+ LKS cells after radiation exposure. Of note, the S/G2/M fraction in both groups remained unchanged after irradiation (data not shown).

Decreased apoptosis and remained quiescence of HSCs in the absence of Puma. (A) Detection of apoptosis of LKS cells by the TUNEL assay. LKS cells sorted from Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice were treated with 4-Gy irradiation. The percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis at 24 hours after irradiation was compared with those without irradiation. Total 250 cells were calculated in each group. Percentage of apoptotic cells in Puma+/+ and Puma−/− was compared using the Fisher exact test. **P < .01. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of cell-cycle change of LKS cells after radiation. G0 versus G1 fraction in cell cycle was measured at 20 hours after 4-Gy irradiation. Representative flow cytometric profiles from 3 experiments were shown (left). The average percentages of G0 fraction in LKS cells from 3 experiments were summarized (right). *P < .05.

Decreased apoptosis and remained quiescence of HSCs in the absence of Puma. (A) Detection of apoptosis of LKS cells by the TUNEL assay. LKS cells sorted from Puma+/+ and Puma−/− mice were treated with 4-Gy irradiation. The percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis at 24 hours after irradiation was compared with those without irradiation. Total 250 cells were calculated in each group. Percentage of apoptotic cells in Puma+/+ and Puma−/− was compared using the Fisher exact test. **P < .01. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of cell-cycle change of LKS cells after radiation. G0 versus G1 fraction in cell cycle was measured at 20 hours after 4-Gy irradiation. Representative flow cytometric profiles from 3 experiments were shown (left). The average percentages of G0 fraction in LKS cells from 3 experiments were summarized (right). *P < .05.

More efficient DNA repair in Puma−/− HSCs after γ-radiation

p53 can influence cell fate following DNA damage in a given cell type depending on the specific effects of its downstream targets.32,34 To investigate the response of DNA repair machinery to radiation damage in HSCs in the absence of Puma, we stained the phosphorylated γ-H2AX, a sensitive and specific indicator of DNA double-strand breaks35 in alive LKS cells. The intensity of γ-H2AX increased by more than 4 times at 12 hours upon irradiation in both Puma+/+ and Puma−/− groups. However, 24 hours after radiation the intensity of γ-H2AX in Puma−/− HSCs rapidly decreased to the level that was comparable with that of nonirradiated HSCs, but it was still high in the Puma+/+ group at 24 hours (Figure 6A-D). We also co-stained γ-H2AX with PCNA, an important protein involved in DNA repair, in irradiated LKS cells. Almost all PCNA foci in the nuclei of radiated HSCs were colocalized with γ-H2AX (supplemental Figure 7), confirming that DNA repair machinery was activated and recruited into the DNA damage sites in irradiated HSCs. Our data strongly indicate that DNA repair machinery in Puma−/− HSCs is activated more efficiently in response to radiation than that in Puma+/+ HSCs.

Confocal microscopy for the expression of γ-H2AX protein. (A-C) Phosphorylated γ-H2AX protein was detected with its antibody and then measured by confocal microscopy at different time points after 4-Gy of γ-irradiation (×40 magnification). (D) Fold change of fluorescence intensity. The intensity of Alexa 488–labeled γ-H2AX was measured by Adobe PhotoshopCS3 imaging process software (Adobe System Inc). The bars show the fold change of mean fluorescence intensity per cell (n = 50 cells picked randomly) compared with that of Puma+/+ nonirradiated group. **P < .01.

Confocal microscopy for the expression of γ-H2AX protein. (A-C) Phosphorylated γ-H2AX protein was detected with its antibody and then measured by confocal microscopy at different time points after 4-Gy of γ-irradiation (×40 magnification). (D) Fold change of fluorescence intensity. The intensity of Alexa 488–labeled γ-H2AX was measured by Adobe PhotoshopCS3 imaging process software (Adobe System Inc). The bars show the fold change of mean fluorescence intensity per cell (n = 50 cells picked randomly) compared with that of Puma+/+ nonirradiated group. **P < .01.

Together, this study suggests an interesting paradigm in which the HSCs spared from radiation exposure in the absence of Puma can be better maintained in a quiescent state, and more efficient DNA repair can be induced, as opposed to Puma+/+ HSCs that are more susceptible to apoptosis following irradiation.

Discussion

We demonstrate in the present study that Puma is a powerful executor of p53-mediated apoptosis in HSCs. Deletion of Puma in hematopoietic cells confers a striking survival advantage to irradiated animals. Importantly, the absence of Puma does not seem to promote malignant transformation. Such a profound beneficial effect of Puma deletion in the context of radiation damage appears to be likely attributed to better maintenance of quiescence and more efficient DNA repair in the exposed stem cells.

Although the involvement of Puma in radiation-induced hematopoietic cell apoptosis is expected based on previous findings in other cell types and models,19,20 the extent to which Puma dominates this process in HSCs is only definitively demonstrated by our current study. Puma belongs to the Bcl-2 family of cell-survival regulators. Although Bcl-2 has been shown to increase HSC numbers in a transgenic model,36 direct evidence for Bcl-2–mediated radioprotection of HSCs is lacking. Compared with other members of the “BH3-only” subfamily such as Bid (H.S., X. Yin, and T.C., unpublished data, August 2007), Puma appears to have a unique and dominant role in regulating apoptotic response of HSCs and HPCs to radiation.

Our current study demonstrates no increase of hematopoietic malignancies in the absence of Puma after high dose γ-irradiation. Moreover, no animals developed hematopoietic malignancies in both primary and secondary recipients after sublethal dose radiation, arguing against the possibility that a failure to increase the frequency of hematopoietic malignancies in the absence of Puma only occurred in higher doses of irradiation. Therefore, there is a disassociation between leukemogenesis and Puma loss at least under some circumstances. This finding is in agreement with a previous report that Puma expression is not altered during the development of BCR/ABL-induced leukemia, a classical HSC malignancy.37 However, we do not intend to exclude the potential role of Puma in tumorigenesis under other conditions. For instance, there are several reports showing an increase of B-cell lymphoma when c-Myc is overexpressed.38 In addition, radiation-associated cancers (if any) may mechanistically differ from those tumors developed without history of radiation exposure. In fact, an earlier study demonstrated that the pathologic response to DNA damage does not contribute to p53-mediated tumor suppression.39 The more efficient DNA repair in Puma−/− HSCs may be because of the presence of p53, which has been shown to negatively regulate error-prone DNA repair.40 Molecular mechanisms underlying no increase of tumorigenesis in certain scenarios are an important subject of our future studies.

In short, unlike p53 that is involved in more than 50% of human cancers as a tumor suppressor, the specific effect (tumor suppression or promotion) of Puma appears to be more context-dependent. Nevertheless, the beneficial effects of inhibiting the p53 pathway may be better achieved by targeting Puma. Our current study strongly justifies Puma as an attractive drug target for developing therapeutic agents in managing radiation-induced damage in patients with minimally increased risk in tumorigenesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Joel Greenberger for his insightful input on this work.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5RO1AI080424 and 5RO1HL070561 to T.C.; 1R01GM083159 and 5P30CA21765 to G.Z.; 1U01DK085570 to J.Y.) and the Ministry of Science & Technology of China (2009CB918900 to T.C.). T.C. was a recipient of the Scholar Award from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (1027-08), the Chang-Jiang Scholarship from the Ministry of Education of China (2007-JGT-08), and the Outstanding Young Scholar Award from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30825017).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: H.Y. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; H.S. performed flow cytometry and cell sorting and analyzed data; Y.Y. wrote the paper; R.X. and X.H. performed bone marrow transplantation; S.P.G. performed the long-term survival assay; L.Z. and J.Y. analyzed data; G.P.Z. contributed Puma−/− mice and provided long-term survival data after lethal irradiation; and T.C. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tao Cheng, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Hillman Cancer Center Research Pavilion, Office Ste 2.42e, 5117 Center Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1863; e-mail: chengt@upmc.edu.