Abstract

Loss of p53-dependent apoptosis contributes to the development of hematologic malignancies and failure to respond to treatment. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Puma is essential for apoptosis in HoxB8-immortalized interleukin-3 (IL-3)–dependent myeloid cell lines (FDM cells) provoked by IL-3 deprivation. p53 and FoxO3a can transcriptionally regulate Puma. To investigate which transcriptional regulator is responsible for IL-3 deprivation-induced Puma expression and apoptosis, we generated wild-type (WT), p53−/−, and FoxO3a−/− FDM cells and found that p53−/− but not FoxO3a−/− cells were protected against IL-3 withdrawal. Loss of p21cip/waf, which is critical for p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, afforded no protection against IL-3 deprivation. A survival advantage was also observed in untransformed p53−/− hematopoietic progenitor cells cultured in the presence or absence of cytokines. In response to IL-3 deprivation, increased Puma protein levels in p53−/− cells were substantially delayed compared with WT cells. Increased p53 transcriptional activity was detected after cytokine deprivation. This was substantially less than that induced by DNA damage and associated not with increased p53 protein levels but with loss of the p53 regulator, MDM2. Thus, we conclude that p53 protein is activated after IL-3 deprivation by loss of MDM2. Activated p53 transcriptionally up-regulates Puma, which initiates apoptosis.

Introduction

The maintenance of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells depends on lineage-specific growth factors, such as interleukin-3 (IL-3). In the absence of cytokine signals, hematopoietic cells exit the cell cycle and commit to apoptosis by pathways regulated by the Bcl-2 family of apoptosis regulators. Evading this commitment permits cells to survive and proliferate in the absence of cytokines and constitutes an important step to tumor formation.1 Understanding the pathways by which cytokine signaling regulates proliferation and suppresses apoptosis in hematopoietic cells provides insight to the abnormal regulation of these responses in hematologic malignancies.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 17p deletions or mutations lose p53 function. This is associated with poorer outcomes and response to treatment, in part, as a result of loss of p53-dependent apoptosis.2,3 In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or AML, loss of p53 may also promote clonogenic proliferation and generation of malignant cells with a stem cell–like phenotype.4 The p53 tumor suppressor functions to regulate the cell cycle and apoptosis in response to a range of cellular stresses such as double-stranded DNA breaks, exposure to genotoxic drugs commonly used to treat malignancies, and abnormal regulation of the cell cycle.5 Other evidence indicates p53 also regulates apoptosis in response to cytokine and substrate deprivation.6,7 p53 also functions to limit the capacity of somatic cells to produce induced pluripotential stem cells through unknown mechanisms.8-11

The mechanism of p53-dependent regulation of apoptosis is primarily through transcriptional regulation of several Bcl-2 family members (reviewed in Lowe et al12 ). The Bcl-2 family of proteins regulates apoptosis induced by a variety of stimuli, including loss of cytokine signaling. Overexpression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members or combined loss of the multidomain proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bax and Bak inhibit cell death provoked by loss of growth factors.13-15 Proapoptotic BH3-only proteins, such as Bim and Puma/Bbc3, possess a single Bcl-2 homology (BH) domain, the BH3 domain. BH3-only proteins have essential roles in the initiation of apoptosis, including apoptosis evoked by cytokine withdrawal. For example, B and T lymphoid cells from Bim−/− mice are resistant to withdrawal of IL-2, IL-7, or other interleukins,16 and hematopoietic progenitor cells derived from Puma−/− mice show increased survival and clonogenicity after cytokine deprivation.13,17

Activation of BH3-only proteins occurs by various mechanisms.18 Puma is predominantly transcriptionally regulated by p53,19-21 the snail family member Slug in response to DNA damage22 and by the Forkhead transcription factor FoxO3a in response to IL-2 deprivation in lymphocytes.23,24 The observation that primary myeloid progenitor cells from the bone marrow of p53−/− mice have enhanced survival when cultured in limiting concentrations of stem cell factor (SCF), IL-3, or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)6 suggests that p53 and p53-regulated genes such as Puma may be involved in the apoptotic response to cytokine deprivation.

To investigate the role of p53 in the response to IL-3 deprivation, we generated IL-3–dependent HoxB8 immortalized myeloid progenitor cell lines (FDM cells) from wild-type (WT), p53−/−, p53+/−, FoxO3a−/−, and FoxO3a+/− mice. We found that loss of p53 but not loss of FoxO3a protected these cell lines from IL-3 withdrawal in short-term and clonogenic assays. Similarly, untransformed hematopoietic progenitors isolated from p53−/− mice were more resistant to apoptosis when cultured in the absence of cytokines compared with their WT counterparts. Puma up-regulation that normally occurs after IL-3 deprivation in WT FDM cells was substantially delayed and diminished in p53−/− cells and is a likely explanation for the enhanced survival and clonogenicity of IL-3–deprived p53-deficient FDM cells.

Methods

Generation of IL-3–dependent FDM cells

FDM cells were generated by HoxB8 transformation as previously described.25 For more information about mouse strains, see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). All FDM cells were cultured in DMEM (low glucose; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; JRH Laboratories) plus 0.25 ng/mL IL-3 (R&D Systems).

Isolation of hematopoietic progenitor cells

Single-cell suspensions of murine E14.5 fetal livers were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/2% FCS before incubation with antibodies specific to lineage markers (anti–TER-119-FITC, anti–Gr-1-FITC, anti–B220-FITC, anti–NK1.1-FITC; BD Scientific) and progenitor markers (anti–sca-1-APC, anti–c-kit-PE; BD Scientific). After incubation at 4°C for 45 minutes, cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS/2% FCS plus propidium iodide (PI; 1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and passed through a 100-μm filter. The c-kit–positive, lineage-negative cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and cultured in DMEM (low glucose) supplemented with 10% FCS with or without SCF (10 ng/mL; Invitrogen) or IL-3 (0.25 ng/mL).

Cell viability assays

IL-3 was removed by washing cells 3 times in PBS and then culturing in DMEM/10% FCS without IL-3. Viability was determined by staining cells with FITC-coupled annexin V (Invitrogen) plus PI (1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) followed by flow-cytometric analysis (LSR II; Becton Dickinson).

Clonogenic survival assays

Clonogenic survival assays were performed as previously described.13,25 Briefly, 1 × 104 cells/mL were cultured in DMEM, 10% FCS with or without IL-3. At various time points, cells were plated in 6-well plates in DMEM, 20% FCS, 0.5 ng/mL IL-3, and 0.3% soft agar. After 14 days the numbers of colonies were counted and expressed as a percentage relative to the number of colonies generated per 1000 cells cultured in IL-3. At least 3 independent clones of each genotype were assayed in each experiment.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell or fractionated lysates were used as indicated. Lysates were boiled in protein sample buffer for 5 minutes and fractionated on 15% or 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; Bio-Rad). See supplemental Methods for additional information.

Cell-cycle analysis

Cell-cycle analysis was performed by staining nuclear DNA of fixed cells with PI (using hypotonic solution) followed by FACS analysis as previously described.26

Cloning and lentiviral expression

The cDNA encoding myristoylated mouse AKT with an N-terminal HA tag (gift from D James, Garvin Institute of Medical Research) and eGFP was cloned into the pF5xUAS-SV40-puromycin lentiviral vector.27 Cells were infected with GEV16 lentivirus and the pF5xUAS-SV40 containing AKT or eGFP. Cells resistant to both hygromycin and puromycin were selected and tested for expression. Expression of HA-myr-AKT or eGFP was induced by 1μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT). A lentiviral construct (pTRF1-p53-dscGFP; System Biosciences) was used as the basis to produce a vector containing the p53 transcription response element for Puma. The sequence CTGCAAGCCCCGACTTGTCC separated by AGA was synthesized (8 repeats; GenScript Cooperation) and then cloned into pTRF1-p53-dscGFP EcoRI/SpeI to produce pTRF1-p53-bbc3 TRE-dscGFP. Transcriptional activity of p53 was detected by FACS analysis of GFP fluorescence intensity.

Expression array analysis

RNA samples were isolated with the use of QIAGEN RNAeasy extraction kit. RNA was labeled, amplified, and hybridized to Illumina MouseWG-6 V1 Expression BeadChips following Illumina standard protocols. Samples were processed at the Australian Genome Research Facility in Melbourne, Australia. For more information see supplemental Methods.

Results

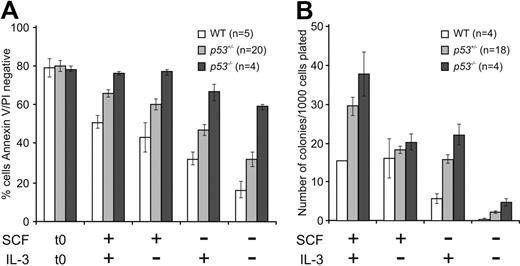

Loss of p53 but not FoxO3a enhances clonogenic survival of FDM cells

Puma is a critical inducer of cytokine withdrawal–induced apoptosis.13,17,24 To investigate which of the proposed transcriptional regulators of Puma implicated in cytokine deprivation was required for apoptosis initiated by IL-3 deprivation, we generated multiple independent clones of HoxB8-immortalized IL-3–dependent myeloid cell lines (referred to as FDM cells) from p53−/−, p53+/−, FoxO3a−/−, FoxO3a+/−, and WT cells. Approximately 90% of WT FDM cells died by 48 hours after removal of IL-3 from the culture media as determined by Annexin V staining and PI uptake with the use of flow cytometry (Figure 1A). Unexpectedly, p53−/− were more resistant to IL-3 withdrawal than WT cells (Figure 1A). The survival of p53−/− cells was similar to the survival we previously observed in Puma−/− cell lines.13 p53+/− FDM cells were as susceptible to IL-3 removal as were WT cells.

Loss of p53 but not loss of FoxO3a confers short-term as well as clonogenic survival advantage to IL-3–dependent HoxB8-immortalized myeloid progenitor cells after cytokine deprivation. (A) Multiple independent IL-3–dependent HoxB8-immortalized myeloid progenitor lines (number of individual clones tested indicated as n) of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 5-day time course. Cell viability was determined by flow cytometry analysis after staining with FITC-conjugated Annexin V plus PI. The results show means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes a P value between WT and p53−/− cells of .0012 at day 1, .0018 at day 2, and .044 at day 5 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). (B) Cells from panel A were plated in soft agar in the presence of IL-3 after the indicated times of culture in the absence of IL-3 (n refers to the number of independent clones analyzed). Colonies were counted after 14 days, and their clonogenicity was determined. The results show means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes P value between WT and p53−/− cells of .019 at day 1, .0051 at day 2, and .023 at day 5 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). (C) Multiple independent FDM lines (numbers indicated as n) of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 2-day time course. Cell viability was determined as described in panel A. The results show means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes a P value between WT and FoxO3a−/− cells of .0025 and between WT and FoxO3a+/− cells of .0023 at day 2 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). (D) Clonogenicity of cells from panel C was determined as described in panel B. Asterisk denotes a P value between WT and FoxO3a−/− cells of .052 and between WT and FoxO3a+/− cells of .015 at day 2 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). The results show means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. (E) Multiple clones (n) of the indicated genotypes were cultured in the presence or absence of doxorubicin for 24 hours before viability was analyzed as described in panel A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments. (F) Multiple clones (n) of the indicated genotypes were subjected to irradiation were then cultured for 24 hours. Viability was analyzed as described in panel A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments.

Loss of p53 but not loss of FoxO3a confers short-term as well as clonogenic survival advantage to IL-3–dependent HoxB8-immortalized myeloid progenitor cells after cytokine deprivation. (A) Multiple independent IL-3–dependent HoxB8-immortalized myeloid progenitor lines (number of individual clones tested indicated as n) of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 5-day time course. Cell viability was determined by flow cytometry analysis after staining with FITC-conjugated Annexin V plus PI. The results show means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes a P value between WT and p53−/− cells of .0012 at day 1, .0018 at day 2, and .044 at day 5 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). (B) Cells from panel A were plated in soft agar in the presence of IL-3 after the indicated times of culture in the absence of IL-3 (n refers to the number of independent clones analyzed). Colonies were counted after 14 days, and their clonogenicity was determined. The results show means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes P value between WT and p53−/− cells of .019 at day 1, .0051 at day 2, and .023 at day 5 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). (C) Multiple independent FDM lines (numbers indicated as n) of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 2-day time course. Cell viability was determined as described in panel A. The results show means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes a P value between WT and FoxO3a−/− cells of .0025 and between WT and FoxO3a+/− cells of .0023 at day 2 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). (D) Clonogenicity of cells from panel C was determined as described in panel B. Asterisk denotes a P value between WT and FoxO3a−/− cells of .052 and between WT and FoxO3a+/− cells of .015 at day 2 with t test (2-tailed, 2-sample equal variance). The results show means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. (E) Multiple clones (n) of the indicated genotypes were cultured in the presence or absence of doxorubicin for 24 hours before viability was analyzed as described in panel A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments. (F) Multiple clones (n) of the indicated genotypes were subjected to irradiation were then cultured for 24 hours. Viability was analyzed as described in panel A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments.

Because short-term cell survival assays do not necessarily correlate with the clonogenic potential of cells,13,25 we also performed colony formation assays to determine whether loss of p53 could enhance long-term survival with retention of proliferative capacity. Cells were deprived of IL-3 for 1, 2, or 5 days before being replated in soft agar in the presence of exogenous IL-3, as previously described.13 Compared with WT FDM cells, cells lacking p53 were significantly more able to form colonies (P = .019 day 1, P = .005 day 2, and P = .023 day 5, 2-tailed t test; Figure 1B). In this assay, p53+/− FDM cells also produced more colonies than WT cells starved of IL-3 for the same time period (P = .094 day 1, P = .22 day 2, and P = .25 day 5, 2-tailed t test).

In contrast, FoxO3a−/− FDM cells had no survival advantage over WT cells in both short-term and clonogenic assays (Figure 1C-D). In fact, FoxO3a−/− cells appeared more susceptible to cell death after IL-3 loss than WT cells in short-term assays (P = .052 day 2 and for clonogenicity P = .003 day 2, 2-tailed t test). The rapid susceptibility of FoxO3a−/− cells to factor withdrawal meant these assays were performed over a 2-day time course. Independent assays of p53−/− FDM cells were done to directly compare the deletion of p53 with the deletion of FoxO3a. p53−/− FDM cells again showed a survival advantage (Figure 1C-D). Together, these results show that, in FDM cells, p53 is critical but FoxO3a is dispensable for IL-3 deprivation–induced apoptosis.

To ensure that p53−/− FDMs cells behaved as expected in response to classical p53-dependent apoptotic stimuli, we treated FDM cell lines lacking p53 or, as a control, FDM cells deficient for both Bax and Bak (which do not release cytochrome c from mitochondria or activate caspases in response to apoptotic stimuli) with doxorubicin for 24 hours or exposed them to γ-irradiation. Cells were then stained with Annexin V and PI, and viability was determined (Figure 1E-F). As anticipated, p53−/− cells were partially protected from these insults compared with WT cells (Figure 1E-F).17,28 Virtually all Bax−/−;Bak−/− cells appeared viable after doxorubicin treatment or exposure to γ-irradiation (Figure 1E-F), indicating that p53-independent but Bax/Bak-dependent processes occur during the apoptotic response to DNA damage in FDM cells.

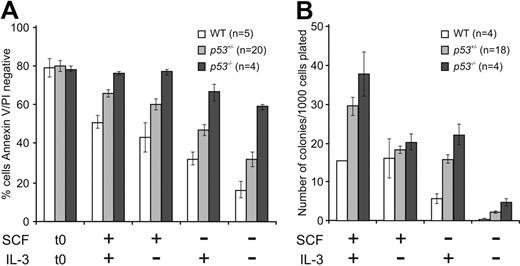

Hematopoietic progenitor cells from p53−/− mice are protected against cytokine withdrawal

It was possible that p53−/− FDM cells have a survival advantage after IL-3 deprivation as a result of HoxB8 overexpression, HoxB8 retroviral integration, or because they have acquired other mutations. To address these possibilities, we examined untransformed early hematopoietic progenitors from WT (p53+/+), p53+/−, or p53−/− E14.5 fetal livers. Cells positive for the SCF receptor c-kit (CD117, which is expressed by hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells) and negative for lineage markers (see “Isolation of hematopoietic progenitor cells”) were isolated with FACS and cultured in the presence or absence of SCF and/or IL-3 (Figure 2). After 24 hours in culture, cell viability was measured. In the absence of IL-3, SCF, or both, significantly more p53−/− cells than WT cells survived (P < .001; Figure 2A). Loss of one allele of p53 conferred a survival advantage (P < .05) but this was not statistically significant in the absence of both cytokines (P = .056). To determine colony formation potential, hematopoietic progenitor cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of SCF and IL-3, the absence of SCF or IL-3, or in the absence of any cytokine and then replated in soft agar with abundant IL-3 and SCF. Remarkably, cells lacking p53 formed more colonies than WT cells in all culture conditions, most obvious in cells cultured only in IL-3 (P = .003) or without any cytokine (P = .007; Figure 2B). p53+/− cells produced an intermediate number of colonies compared with WT FDM cells (P = .012 for cells initially cultured in the absence of cytokine). These results indicate that untransformed p53−/− hematopoietic cells show prolonged survival and enhanced clonogenicity after cytokine withdrawal and that the resistance to cytokine deprivation afforded by p53 loss does not require HoxB8 transformation.

Loss of p53 confers clonogenic survival advantage to primary hematopoietic progenitor cells after cytokine deprivation. (A) Early hematopoietic progenitor cells were isolated from fetal livers of WT (p53+/+), p53+/−, or p53−/− E14.5 embryonic mice (n indicates the numbers of embryos analyzed). The c-kit (CD117)–positive and Lineage (Lin)–negative cells were sorted with the use of FACS and cultured in the presence or absence of SCF or IL-3 or both. After 24 hours in culture, cell viability was analyzed as described in Figure 1A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. (B) Cells from panel A were placed into soft agar containing IL-3 plus SCF, and their clonogenicity was determined by counting colonies after 14 days. The n refers to the numbers of embryos analyzed (the n of WT cells cultured in the presence of SCF and IL-3 was 2). The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments.

Loss of p53 confers clonogenic survival advantage to primary hematopoietic progenitor cells after cytokine deprivation. (A) Early hematopoietic progenitor cells were isolated from fetal livers of WT (p53+/+), p53+/−, or p53−/− E14.5 embryonic mice (n indicates the numbers of embryos analyzed). The c-kit (CD117)–positive and Lineage (Lin)–negative cells were sorted with the use of FACS and cultured in the presence or absence of SCF or IL-3 or both. After 24 hours in culture, cell viability was analyzed as described in Figure 1A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. (B) Cells from panel A were placed into soft agar containing IL-3 plus SCF, and their clonogenicity was determined by counting colonies after 14 days. The n refers to the numbers of embryos analyzed (the n of WT cells cultured in the presence of SCF and IL-3 was 2). The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments.

Regulation of p53 protein levels and p53 transcriptional activity in cells exposed to DNA-damaging drugs or cytokine deprivation

Because deletion of p53 resulted in increased survival after IL-3 deprivation, we wanted to determine whether p53 protein levels increased after IL-3 withdrawal and whether IL-3 withdrawal was associated with increased p53 transcriptional activity. Endogenous p53 levels are below the limits of detection with Western blotting in FDM cells27 ; however, in FDMs treated with doxorubicin, induction of p53 expression could readily be detected (Figure 3A). In contrast, p53 protein levels in WT or Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells starved of IL-3 remained below detectable limits in whole-cell lysates (Figure 3A) or the nuclear fractions (supplemental Figure 1).

FDM cells express negligible levels of p53 after IL-3 withdrawal, but p53 reporter activity is slightly elevated. (A) Cells of the indicated genotypes were either treated with doxorubicin (in the presence of IL-3) or deprived of IL-3. Whole cell lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to p53 and β-actin (loading control). (B) Cells of the indicated genotypes were lentivirally transduced with a construct encoding a p53 transcriptional response element from the Puma promoter linked to GFP. p53 Transcriptional activity (GFP fluorescence intensity) was measured 24 hours after γ-irradiation or (C) 6 and 24 hours after cytokine withdrawal. The results shown are means ± SEMs of3 independent experiments, and n refers to the number of independent clones in each experiment. Asterisks denote a P value of .02, comparing Bax−/−;Bak−/− GFP expression before (time 0) and 24 hours after IL-3 withdrawal with the use of a t test (1-tailed, paired analysis).(D) Representative FACS plots of panels B and C are shown.

FDM cells express negligible levels of p53 after IL-3 withdrawal, but p53 reporter activity is slightly elevated. (A) Cells of the indicated genotypes were either treated with doxorubicin (in the presence of IL-3) or deprived of IL-3. Whole cell lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to p53 and β-actin (loading control). (B) Cells of the indicated genotypes were lentivirally transduced with a construct encoding a p53 transcriptional response element from the Puma promoter linked to GFP. p53 Transcriptional activity (GFP fluorescence intensity) was measured 24 hours after γ-irradiation or (C) 6 and 24 hours after cytokine withdrawal. The results shown are means ± SEMs of3 independent experiments, and n refers to the number of independent clones in each experiment. Asterisks denote a P value of .02, comparing Bax−/−;Bak−/− GFP expression before (time 0) and 24 hours after IL-3 withdrawal with the use of a t test (1-tailed, paired analysis).(D) Representative FACS plots of panels B and C are shown.

Because no increase in p53 protein levels could be detected by Western blotting, we next determined whether p53 transcriptional activity was altered after IL-3 deprivation. WT, p53−/−, and Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells were transduced with a lentiviral p53-GFP reporter construct containing several continuous repeats of the p53 binding site of the Puma gene linked to a sequence encoding GFP (see “Cloning and lentiviral expression”). Treatment of these cells with γ-irradiation (10 Gy) increased GFP levels, as detected by FACS, in WT and Bax−/−;Bak−/− cells but not in p53−/− cells, showing the specificity of this reporter (Figure 3B,D). Interestingly, 24 hours after IL-3 withdrawal, a subtle increase in GFP fluorescence was detected in Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells but not in WT cells (Figure 3C-D). This was many fold less than that observed after γ-irradiation. We reasoned that we did not observe an increase in p53 reporter activity in WT cells because, unlike Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells, these cells die before p53 GFP reporter activation reaches detectable limits. Collectively, these data indicate that IL-3 withdrawal resulted in a subtle increase in p53 transcriptional activity but not p53 protein levels detectable with the use of Western blotting. The increase in p53 transcriptional activity is substantially less than that which follows DNA damage.

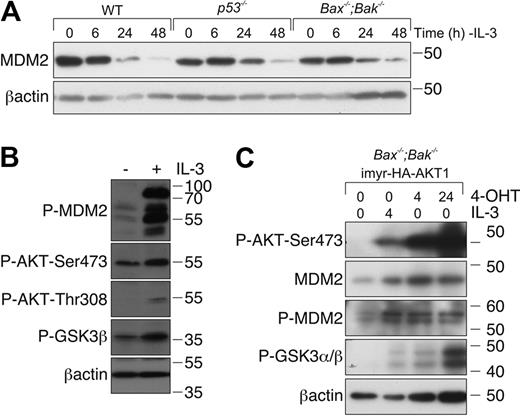

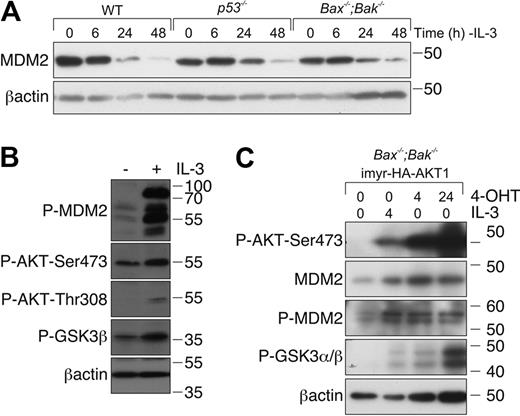

MDM2 protein levels decrease after cytokine deprivation

MDM2 is a major negative regulator of p53 that binds directly to p53 and promotes its poly-ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.29 MDM2 stability can be regulated by phosphorylation by several kinases, including AKT, which is activated during IL-3/IL-3R signaling.30,31 We therefore reasoned that, in the absence of a detectable increase in p53 protein, loss of IL-3 signaling might result in dephosphorylation and inactivation of MDM2, resulting in an increased pool of transcriptionally active p53. To examine this, we used Western blotting to assess MDM2 levels in lysates from WT, p53−/−, and Bax−/−;Bak−/− cells cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3. MDM2 levels declined over 48 hours of IL-3 starvation in all genotypes (Figure 4A). Because Bax−/−;Bak−/− cells are resistant to apoptosis induced by IL-3 deprivation, we could exclude the possibility that the decline in MDM2 levels was the consequence of cell death. Consistent with the notion that IL-3/IL-R signaling regulates MDM2 levels, readdition of IL-3 increased MDM2 levels in Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells deprived of IL-3. This was accompanied by activation of AKT, as indicated by increased phosphorylated AKT, and increased phosphorylation of the AKT substrate GSK3 (Figure 4B).

IL-3 deprivation results in a reduction of MDM2 levels. (A) FDM cell lines of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to MDM2 and β-actin (loading control). (B) FDM cell lines were deprived of IL-3 for 48 hours before being restimulated with 0.25 ng/mL IL-3 for 20 minutes. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to pMDM2, P-AKT-Ser473, P-AKT-Thr308, P-GSK3β, and βactin (loading control). (C) Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells were infected with a lentiviral system that allows inducible expression of constitutively active AKT1. Cells were starved of IL-3 for 48 hours (denoted as time 0) before being restimulated with 0.25 ng/mL IL-3 or treated with 4-OHT to induce expression of AKT. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to P-AKT-Ser473, MDM2, P-MDM2, P-GSK3α/β, and β-actin (loading control).

IL-3 deprivation results in a reduction of MDM2 levels. (A) FDM cell lines of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to MDM2 and β-actin (loading control). (B) FDM cell lines were deprived of IL-3 for 48 hours before being restimulated with 0.25 ng/mL IL-3 for 20 minutes. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to pMDM2, P-AKT-Ser473, P-AKT-Thr308, P-GSK3β, and βactin (loading control). (C) Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells were infected with a lentiviral system that allows inducible expression of constitutively active AKT1. Cells were starved of IL-3 for 48 hours (denoted as time 0) before being restimulated with 0.25 ng/mL IL-3 or treated with 4-OHT to induce expression of AKT. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to P-AKT-Ser473, MDM2, P-MDM2, P-GSK3α/β, and β-actin (loading control).

To determine whether AKT was sufficient to promote MDM2 phosphorylation, we used Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells transduced with a vector system that allowed 4-OHT–inducible expression of an active form of AKT (see “Cloning and lentiviral expression”). After IL-3 deprivation for 48 hours, cells were restimulated with either IL-3 or 4-OHT. IL-3 increased AKT phosphorylation at serine 473 and the phosphorylation of the AKT substrate GSK3. IL-3 readdition resulted in an increase in MDM2 phosphorylation. 4-OHT treatment (independent of IL-3) increased the expression of phosphorylated AKT maximally by 24 hours and was sufficient to increase the levels of phosphorylated MDM2 (Figure 4C). These data show that IL-3/IL-3R signaling, in part at least through AKT activation, regulates phosphorylation and activity of MDM2. This probably accounts for the p53 reporter activity observed in FDM cells after IL-3 withdrawal (Figure 3C).

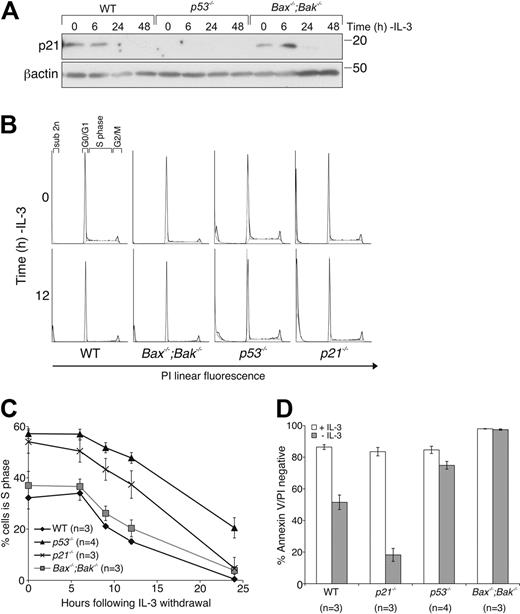

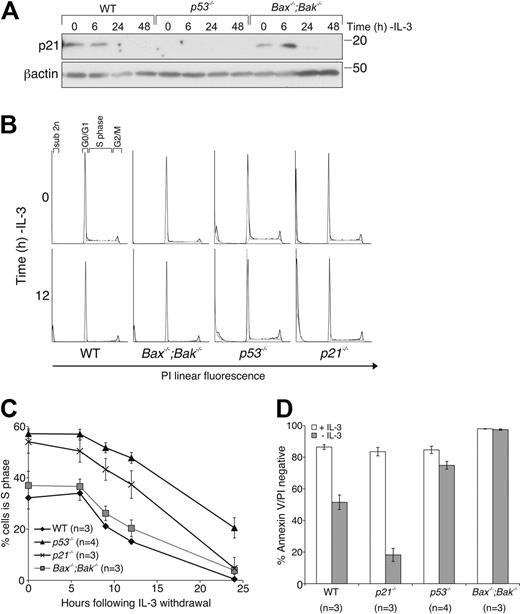

Loss of p21cip/waf does not confer a survival advantage in response to cytokine deprivation

The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21 is a transcriptional target of p53 and has curiously been reported to enhance or inhibit apoptosis in response to cytokine withdrawal.32,33 To determine whether the enhanced survival of IL-3–deprived p53−/− FDM cells could be accounted for by altered p21 expression, we determined the effect of deletion of p21 on the response to IL-3 withdrawal. In response to IL-3 withdrawal, p21 protein levels increased transiently (maximum at 6 hours), most readily observed in Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells (Figure 5A). The CDK inhibitor p27 was up-regulated after IL-3 withdrawal in WT, p53−/−, and Bax−/−;Bak−/− cell lysates (supplemental Figure 2). Predictably, no p21 increase was seen in lysates from p53−/− FDM cells. We next generated FDM cells from p21−/− mice.34 Cell-cycle analysis of WT, p21−/−, p53−/−, and Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells cultured either in the presence or absence of IL-3 (Figure 5B-C) indicated that the proportion of cells in S phase in the presence of IL-3 was higher in p53−/− and p21−/− FDM cells than in WT or Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells. After cytokine withdrawal, more p53−/− cells remained in S phase compared than WT or Bax−/−;Bak−/− cells. The percentages of p21−/− cells in S phase rapidly declined after IL-3 deprivation, similar to the decline observed in WT and Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells (Figure 5B-C). When the viability of these cells was determined, notably, p21−/− FDM cells were more susceptible to IL-3 deprivation than were WT cells (Figure 5D), which probably explained the rapid decline of p21−/− cells residing in S phase. Interestingly, although p53−/− cells exhibited a delayed decline in the percentage of cells in S phase, cells remained viable at 24 hours, showing that loss of IL-3 induced cell-cycle arrest in p53−/− cells before cell death. Collectively, these data indicate that the protection from IL-3 deprivation induced apoptosis of FDM cells afforded by loss of p53 is not due to failure of transcriptional activation of its target p21. Instead, p21 induction can delay initiation of cell death by preventing entry into S phase, a cell-cycle stage when cells appear to have increased propensity to initiate apoptosis.35

Loss of p21 does not protect FDM cells from cytokine deprivation, although loss of p53 delays cell-cycle exit. (A) FDM cells of the indicated genotype were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to p21 and β-actin (loading control). (B) Cells of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 24-hour time course. Cell-cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis. Representative FACS plots are shown for time 0 and 12 hours. (C) Cell-cycle distribution was analyzed for multiple independent clones (n) of the indicated genotypes as in panel B. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. (D) Multiple clones (n) of the indicated genotypes were cultured in the absence of IL-3 for 24 hours before cell viability was analyzed as described in Figure 1A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments.

Loss of p21 does not protect FDM cells from cytokine deprivation, although loss of p53 delays cell-cycle exit. (A) FDM cells of the indicated genotype were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to p21 and β-actin (loading control). (B) Cells of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 24-hour time course. Cell-cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis. Representative FACS plots are shown for time 0 and 12 hours. (C) Cell-cycle distribution was analyzed for multiple independent clones (n) of the indicated genotypes as in panel B. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments. (D) Multiple clones (n) of the indicated genotypes were cultured in the absence of IL-3 for 24 hours before cell viability was analyzed as described in Figure 1A. The results shown are means ± SEMs of 4 independent experiments.

Loss of p53 inhibits Puma up-regulation in IL-3–deprived FDM cells

Because Puma is a p53-regulated BH3-only protein important in apoptosis after IL-3 deprivation, we determined whether loss of p53 resulted in decreased Puma expression after cytokine withdrawal. Lysates from p53−/− cells deprived of IL-3 for 0, 6, 24, and 48 hours were run on SDS-PAGE and probed with a Puma-specific antibody. As before,13 Puma levels increased in WT FDM cells, most prominently after 6 hours (Figure 6). Interestingly, some Puma up-regulation was evident in p53−/− FDM cells, but this was less than in WT cells (Figure 6), and was delayed, becoming evident only after 48 hours of cytokine deprivation (Figure 6). Western blots probed with an antibody against Noxa, another p53-inducible proapoptotic protein,36 showed that Noxa levels declined steadily after IL-3 deprivation in WT and p53−/− FDM cells (Figure 6). The specificity of the anti-Noxa antibody was established by probing lysates derived from Noxa−/− FDM cells (supplemental Figure 3). Noxa was detectable in p53−/− FDM cells at levels comparable with those seen in WT FDM cells, indicating that p53 is not required for Noxa expression in these cells. This is consistent with previous results showing that HoxB8 transformed myeloid cells derived from Noxa−/−;Puma−/− cells do not have a significant survival advantage compared with Puma−/− FDM cell lines.13 Together these data suggest that the initial up-regulation of Puma after the loss of IL-3 in myeloid cells is mediated by p53, and this mechanism explains, in part at least, the protection of p53−/− cells against IL-3 deprivation.

Loss of p53 delays Puma up-regulation in IL-3–deprived FDM cell lines. (A) Cells of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to Puma, Noxa, and β-actin (loading control).

Loss of p53 delays Puma up-regulation in IL-3–deprived FDM cell lines. (A) Cells of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to Puma, Noxa, and β-actin (loading control).

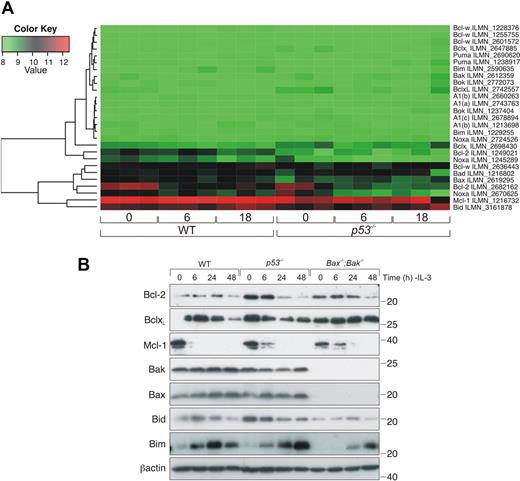

Expression of apoptosis regulatory genes in WT and p53−/− FDM cell lines

To analyze whether transcriptional regulation of other apoptosis genes differed between WT and p53−/− FDM cells after IL-3 deprivation, RNA samples from 3 independent clones each of WT and p53−/− FDM cells, 0, 6, and 18 hours after IL-3 withdrawal, were analyzed with the Illumina MouseWG-6 Expression BeadChip array (Figure 7A). There were few differences in the expression levels of apoptosis regulatory genes between WT and p53−/− cells in the presence of IL-3, which suggested that p53−/− cells did not have a gene expression profile more conducive to survival compared with WT cells (eg, higher expression of antiapoptotic genes or lower expression of proapoptotic genes; Figure 7A; supplemental Table 1). Withdrawal of IL-3 over an 18-hour time course did not change the expression profile of most apoptosis regulatory genes. However, Bcl-2 expression levels declined after IL-3 deprivation in WT and p53−/− cells (Figure 7A; supplemental Table 2). Western blotting confirmed a decrease in Bcl-2 protein levels over a 48-hour time course in p53−/−, Bax−/−;Bak−/−, and WT cells (Figure 7B; supplemental Figure 4). We also confirmed by Western blotting that there were no substantial differences in other key Bcl-2 family members between WT and p53−/− FDM cell lines after IL-3 withdrawal (Figure 7B). The apparently elevated expression levels of Bid in p53−/− cells is best explained by clonal variation and not a specific p53-dependent difference, as indicated by Western blot analysis of several independently generated cell lines (supplemental Figure 5). Although we have previously been unable to detect Bim convincingly in FDM cells,27 we did detect an increase after IL-3 withdrawal with the use of the anti-Bim 3C5 antibody (Alexis). Notably, no significant changes in Puma mRNA levels after IL-3 withdrawal were detected by array analysis in WT or p53−/− cells, although we have previously detected an increase in Puma mRNA and protein expression in cytokine-deprived FDM cell lines13 and have again validated that observation here (Figure 6). Variability between the biologic replicates we have used in the array may limit detection of a subtle increase in Puma mRNA. Further, it was clear that changes in expression as determined by some array probes did not reflect changes in protein expression. For example, one Noxa probe and one Bcl-2 probe did not detect declines in Noxa or Bcl-2 protein that were detected by other Noxa and Bcl-2 probes and by Western blotting. Consistent with previously reported arrays,37,38 mRNA levels of PIM kinases declined in our microarray analysis after cytokine starvation in both WT and p53−/− cells (supplemental Table 3). Collectively, these results indicate that IL-3 deprivation causes only limited changes in transcription of apoptosis regulatory genes in FDM cells and that p53 has no marked effect on this expression profile.

IL-3 deprivation causes a decrease in Bcl-2 mRNA levels in both WT and p53−/− FDM cell lines. (A) Three independent WT and p53−/− FDM cell clones were deprived of IL-3 for 6 or 18 hours. RNA was extracted, and gene profiles were analyzed with the use of the 6-chip Illumina expression array. Heatmap depicts the expression of key Bcl-2 family genes. (B) FDM cells of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, Bak, Bax, Bid, Bim, and β-actin (loading control).

IL-3 deprivation causes a decrease in Bcl-2 mRNA levels in both WT and p53−/− FDM cell lines. (A) Three independent WT and p53−/− FDM cell clones were deprived of IL-3 for 6 or 18 hours. RNA was extracted, and gene profiles were analyzed with the use of the 6-chip Illumina expression array. Heatmap depicts the expression of key Bcl-2 family genes. (B) FDM cells of the indicated genotypes were deprived of IL-3 over a 48-hour time course. Lysates were prepared, and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with antibodies to Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, Bak, Bax, Bid, Bim, and β-actin (loading control).

Discussion

The regulation of apoptotic pathways and Bcl-2 family members by p53 has important consequences in hematologic malignancy. The p53 tumor suppressor is deleted or has loss-of-function mutations in many hematologic malignancies. For example, approximately 5% of AML cases have loss or mutation of p53, and this confers a poorer prognosis and predicts treatment failure. In CLL, loss of p53, as a result of 17p deletion with or without mutation of the other p53 allele, is associated with poor prognosis and failure to respond to treatment.39 p53-Dependent apoptotic pathways are also important in the response to chemotherapy. Many chemotherapeutic agents function, in part at least, by inducing apoptosis through p53-dependent up-regulation of proapoptotic BH3-only proteins such as Puma.17,28,40 This is part of the rationale behind the trial of new drugs that inhibit antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members, allowing Bax and Bak activation, eg, ABT-263 and obatoclax, in malignancies such as CLL. These drugs can directly bypass p53 deletion to engage the apoptotic pathway. We show here that deletion of p53 also prolongs survival of myeloid progenitor cells after a different kind of apoptotic stimulus, deprivation of cytokines such as IL-3.

Our observation that loss of p53 protects nontransformed hematopoietic progenitor cells from cytokine deprivation–induced apoptosis supports earlier demonstrations that p53−/− bone marrow–derived myeloid progenitors survived longer in limiting cytokine doses.6 The concordance of results from HoxB8 transformed and untransformed myeloid progenitors indicate that HoxB8 transformation of FDM cells does not account for the effects of p53 deficiency that we observed.

The enhanced clonogenicity of primary and transformed myeloid progenitor cells that lack one or both copies of p53, in the presence of cytokine or after cytokine deprivation, may not solely be attributable to loss of p53-dependent apoptotic pathways. Each p53+/− or p53−/− cell may also have a greater ability to generate a colony than its WT counterpart, through loss of normal p53 regulation of the cell cycle. The protection observed in transformed cells lacking one copy of p53 is most likely explained by haploinsufficiency and not by loss of heterozygosity. This is shown when p53+/− cells (expressing a p53 reporter) retained p53 reporter activity after they were deprived of IL-3 and were resupplemented with IL-3 in clonogenic experiments (supplemental Figure 6). In fact, loss of reporter activity was a rare event in both WT and p53+/− cells. In other studies, deletion of p53 enhanced the ability of somatic cells to produce induced pluripotential stem cells.8-11 These results suggest that the oncogenic effects of p53 deletion in tumors, particularly hematologic malignancies, may be a result of deregulated proliferation and differentiation and the aberration of the p53-dependent apoptosis response.

FoxO3a, a member of the Forkhead transcription factor family, can transcriptionally up-regulate both Puma and Bim in growth factor–deprived cells, in a manner that is negatively regulated by AKT.23 Furthermore, mast cells from FoxO3a-deficient mice survived significantly better than their WT counterparts in the absence of IL-3.24 Surprisingly, FoxO3a−/− FDM cells did not have any survival advantage when starved of IL-3. Differences in cell type and/or cytokine specificity may account for these divergent results, although loss of FoxO3a protected mast cells for the first 48 hours after IL-3 withdrawal (clonogenic assays were not performed), and these cells still expressed Puma (and Bim) in response to IL-3 deprivation.24 Nevertheless, it is likely that several transcription factors contribute to the apoptotic response to cytokine deprivation by activating BH3-only proteins. Our data do not exclude transcription factors in addition to p53-promoting Puma up-regulation during IL-3 deprivation. Indeed, Puma expression did increase slowly in IL-3–deprived p53−/− FDM cells compared with WT cells. Similarly, p53−/− IL-2–dependent lymphoid cells up-regulated Puma expression after IL-2 withdrawal, although less so than WT cells.23 These results indicate that several transcriptional mechanisms are involved in up-regulated Puma expression after cytokine deprivation, and these may vary between different cell types and cytokine-signaling pathways.

Our data help clarify the role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in cytokine deprivation–induced apoptosis. Previously published data suggested that enforced expression of p21 sensitized differentiating granulocytes to IL-3 withdrawal–induced apoptosis,41 whereas monocytes overexpressing p21 displayed enhanced resistance to apoptotic stimuli.42 We found that p21−/− FDM cells are abnormally sensitive to IL-3 deprivation, indicating that p21-mediated G1 cell-cycle arrest delays apoptosis in these growth factor–deprived cells. Because p53−/− FDM cells have insignificant p21 protein levels, p21 does not contribute to the prosurvival phenotype of p53−/− FDM cells. Because p21−/− and p53−/− FDM cells grown in IL-3 have a higher percentage of cells in S phase compared with WT FDM cells, both p21 and p53 have important roles in the normal regulation of the cell cycle in FDM cells. After IL-3 removal, p53−/− cells exited the cell cycle more slowly than WT cells. However, p53−/− cells did ultimately undergo cell-cycle arrest. This was probably mediated by induction of the CDK inhibitor, p27, which increased in expression after growth factor withdrawal in a p53-independent manner.43

We observed a more subtle increase in p53 transcriptional activity after IL-3 withdrawal than what Zhao et al7 detected in growth factor–deprived FL.5 cells with the use of a luciferase reporter. A reliable increase in p53 reporter activity could only be seen in IL-3–deprived Bax−/−;Bak−/− FDM cells, probably because the WT FDM cells died before a response could be detected. A proportion of WT FDM cells had detectable p53 reporter activity in the presence of IL-3 and the absence of any DNA-damaging stimuli. This basal expression of p53, distinct from the p53 induction seen in response to DNA damage, may have important physiologic roles,44 including during growth factor withdrawal. The hematopoietic system of p53−/− mice contain increased numbers of myeloid progenitors, and in cultures containing cytokines these cells exhibit increased cell cycling and greater clonogenic potential than do WT counterparts.45 We also observed increased clonogenic potential in untransformed p53−/− myeloid progenitors. Combined, this suggests that p53 is required for normal quiescence of myeloid progenitors and that p53 activity in healthy cells may also regulate survival of these cells in the absence of cytokines.

Instead of increased p53 protein levels in response to IL-3 deprivation, we observed that cytokine deprivation resulted in a decline in MDM2 levels and that readdition of IL-3 resulted in MDM2 phosphorylation. This is consistent with regulation of MDM2 by IL-3/IL-3R signaling controlling the ability of p53 to transcriptionally up-regulate Puma and to promote apoptosis. The most likely model to account for such regulation would be that IL-3/IL-3R signaling activates kinases that phosphorylate MDM2. Cytokine deprivation would diminish this kinase activity and would result in MDM2 de-phosphorylation and degradation. Pertinently, AKT (also called PKB) kinase is activated during IL-3 signaling,46,47 and MDM2 was recognized as an AKT substrate in the context of combined growth factor deprivation and DNA damage.48 Here, we demonstrated that AKT was sufficient to promote MDM2 phosphorylation in the absence of IL-3/IL-3R signaling. AKT activity may explain the observation that p53-dependent up-regulation of Puma, after IL-3 loss, is suppressed by maintenance of normal cellular glucose or enforced expression of Glut1/Hexakinase.7 Because AKT has an important role in maintaining glucose uptake, it is possible that AKT both maintains cellular glucose and suppresses p53 transcriptional activity in the presence of IL-3 and that both activities are lost when cells are deprived of IL-3.

We conclude that IL-3/IL-3R signaling controls the baseline level and transcriptional activity of p53, most likely through AKT-mediated regulation of MDM2, to promote myeloid cell survival by suppressing Puma expression. When cells are deprived of IL-3 (and possibly other cytokines), p53-dependent up-regulation of Puma results in the killing of growth factor–dependent cells. In the context of DNA damage, the proapoptotic activity of p53 appears to be dispensable for its ability to suppress tumorgenesis.49 It remains to be determined whether the regulation of cytokine withdrawal induced apoptosis (and maybe also cell-cycle arrest) by p53 contributes to its tumor suppressor activity.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs D. L. Vaux, J. Silke, B. Callus, and D. C. S. Huang for valuable discussions and providing reagents and Drs N. Motoyama and S. Cory for use of the FoxO3a mice. We also thank Drs M. Burton for help with FACS analysis and E. Michalak for providing us with p21 null mice.

This work was supported by the National Health and Research Council (NHMRC; project grants 384404 and 43693; program grant 257502, A.S.; CDA 461274, C.J.V.); the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; BO-1933, C.B., S.V.); the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (Spemann Graduate School of Biology and Medicine [SGBM], GSC-4, Centre for Biological Signaling Studies, bioss, EZC 294, C.B., S.V.); the Jose Carreras Leukemia Foundation of Germany (DJCS; R 06/09, C.B.); and by The Melbourne University Early Career Researcher Grant (A.M.J.). S.L.N. is supported by the Pfizer Australia Research Fellowship, and P.G.E. is supported by the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Senior Medical Fellowship.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.M.J. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; C.P.D., B.D.G., S.V., and R.S.L. performed research; L.G. analyzed data; N.S., P.N.K., and C.J.V. generated vital reagents; R.B.P., S.L.N., A.S., and C.B. designed research; and P.G.E. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anissa M. Jabbour, Children's Cancer Centre, Royal Children's Hospital, Flemington Rd, Parkville, VIC, 3052 Australia; e-mail: anissa.jabbour@mcri.edu.au; or Paul G. Ekert, Children's Cancer Centre, Royal Children's Hospital, Flemington Rd, Parkville, VIC, 3052 Australia; e-mail: paul.ekert@rch.org.au.