Abstract

The von Willebrand factor (VWF) A2 crystal structure has revealed the presence of a rare vicinal disulfide bond between C1669 and C1670, predicted to influence domain unfolding required for proteolysis by ADAMTS13. We prepared VWF A2 domain fragments with (A2-VicCC, residues 1473-1670) and without the vicinal disulfide bond (A2-ΔCC, residues 1473-1668). Compared with A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC exhibited impaired proteolysis and also reduced binding to ADAMTS13. Circular dichroism studies revealed that A2-VicCC was more resistant to thermal unfolding than A2-ΔCC. Mutagenesis of C1669/C1670 in full-length VWF resulted in markedly increased susceptibility to cleavage by ADAMTS13, confirming the important role of the paired vicinal cysteines in VWF A2 domain stabilization.

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (VWF) forms disulfide-linked multimers, the largest of which are most potent in binding collagen and the platelet receptor glycoprotein Ibα.1-4 Mechanical shear forces in the bloodstream induce conformational changes in VWF5 and modulate the exposure of both platelet and ADAMTS13-binding sites. VWF multimer size and function are regulated through proteolysis by ADAMTS13.6,7 Unfolding of the central VWF A2 domain is required to expose the Y1605-M1606 cleavage site, which is normally buried within the central β-sheet of the domain.8

The VWF A2 domain is highly homologous to the VWF A1 and A3 domains (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) but lacks an intradomain disulfide bond that connects the β1-sheet with the α6-helix. However, the recent VWF A2 domain crystal structure revealed a disulfide bond between adjacent C1669 and C1670 at the C-terminus of the α6-helix.8 Such a vicinal disulfide bond is rare, as an 8-membered ring is formed that bends the protein backbone in an unusual constrained conformation.9 In the crystal structure, the disulfide bond directly interacts to the hydrophobic core of the domain, suggesting that it stabilizes the domain conformation.8 We therefore examined the influence of this unusual vicinal disulfide bond on VWF A2 domain function.

Methods

Recombinant proteins

VWF A2-ΔCC (amino acids 1473-1668), A2-VicCC (1473-1670), and both N1493C/C1669G (A2-CC1) and N1493C/C1670G (A2-CC2) mutants (supplemental Figure 1B) were cloned in the pCEP4 vector (Invitrogen) containing a C-terminal myc/His tag. A2 domain fragments were expressed in HEK293EBNA cells, purified by Ni2+ chromatography, and quantified by the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific).

Mutations N1493C/C1669G (VWF-CC1), N1493C/C1670G (VWF-CC2), and C1669G/C1670G (VWF-VicGG) were introduced into pcDNA3.1-VWF10 and full-length VWF variants expressed in HEK293EBNA cells. Conditioned media were dialyzed and VWF concentrations determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.10 ADAMTS13 was expressed and purified as previously described.11

Maleimide-PEG2-biotin labeling of free thiols

Free thiols were detected both before and after reduction of VWF A2 variants by labeling with maleimide-PEG2-biotin (Thermo Scientific). Labeled thiols were detected by Western blotting using streptavidin-peroxidase.

Reduction and carboxymethylation of VWF A2 variants

To permanently disrupt disulfide bonds, VWF A2 variants were reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT) and carboxymethylated with iodoacetic acid before use in the proteolysis and binding assays.

Proteolysis by ADAMTS13

Proteolysis of VWF A2 variants was performed as previously described.12 After proteolysis, samples were reduced by incubation with 50mM DTT and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with silver staining. Proteolysis of full-length VWF was performed as described.13

Binding of ADAMTS13 to VWF A2 variants

Circular dichroism of VWF A2 domain fragments

Measurements were performed on a Chirascan CD Spectophotometer (Applied Photophysics) using a 1-mm path-length quartz cell. VWF A2 domain fragments were in 20mM Tris, pH 7.8, 50mM NaCl, and a molecular weight of 38 kDa was used for calculations. For thermodynamic stability, circular dichroism (CD) measurements at 222 nm were performed between 20°C and 80°C.

Results and discussion

The C1669/C1670 vicinal disulfide bond protects VWF A2 from proteolysis by ADAMTS13

To study the influence of the vicinal disulfide bond, we generated VWF A2 domain fragments either with (A2-VicCC) or without (A2-ΔCC; supplemental Figure 1) the 2 vicinal cysteines. Disulfide bond formation between C1669 and C1670 in A2-VicCC was confirmed by maleimide-PEG2-biotin labeling. Only a small amount of biotinylated A2-VicCC was detected, suggesting that the vicinal disulfide bond was formed in the majority of A2-VicCC, with only a small proportion remaining in a reduced state (Figure 1A).

Comparative analysis of VWF A2-ΔCC and A2-VicCC. (A) Purified VWF A2-VicCC was detected on a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel (lane 1). VWF A2-ΔCC was incubated with maleimide-PEG2-biotin (MBP) without (NR, lane 2), and with prior reduction by incubation with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) agarose beads (lane 3, R). Afterward, reactions were quenched with reduced L-glutathione. Biotin-labeled sulfhydryl groups were detected on Western blot using peroxidase-labeled streptavidin. The same samples were also detected on Western blot using c-myc monoclonal antibody to control for equal loading (lanes 4 and 5). (B) Recombinant ADAMTS13 (2nM) was preincubated with 5mM CaCl2 for 1 hour at 37°C. Then, 2μM VWF A2-ΔCC or A2-VicCC (NR) variant and 1.5M urea were added and samples were taken at the indicated time points (0-3 hours). Reactions were stopped by the addition of 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. We simultaneously also performed this assay using A2-VicCC that was reduced with 10mM DTT, then carboxymethylated with 20mM iodoacetic acid, and afterward quenched with 40mM DTT and extensively dialyzed before use in the activity assay (A2-VicCC R). Samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. On proteolysis by ADAMTS13, the N- and C-terminal cleavage fragments became apparent. The experiment was performed 3 times; a representative result is shown. (C) Binding of serial dilutions of purified ADAMTS13 to 50nM immobilized VWF A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC (NR) and reduced and carboxymethylated VWF A2-VicCC (R). The assay was performed in the presence of 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to prevent proteolysis. Bound ADAMTS13 was detected using biotinylated anti–TSR2-4 polyclonal antibodies, followed by streptavidin-peroxidase. Binding curves were generated using GraphPad Prism software, fitting the data to the one-binding site equation. (D) Purified ADAMTS13 (30nM) was preincubated for 1 hour with 0 to 600nM soluble A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC (NR), and reduced and carboxymethylated A2-VicCC (R). After preincubation, the mixture was added to wells with 50nM immobilized VWF A2-ΔCC, and ADAMTS13 was allowed to bind for 1 hour in the presence of the soluble VWF A2 variants. Bound ADAMTS13 was then detected as in panel C. Curves were fitted to a one-site competition model using GraphPad Prism software. (E) CD spectra of VWF A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC, A2-CC1, and A2-CC2 at 20°C. Measurements were taken over 190 to 260 nm, at a 0.5-nm interval, bandwidth 1 nm, 1 second per data point. Data were converted to mean residue molar ellipticity, and averages of 6 to 12 measurements are shown. (F) Change in mean residue molar ellipticity on increase of temperature at 5°C intervals from 20°C to 80°C, as determined at 222 nm. Averages of 5 measurements are shown. Curves were plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Comparative analysis of VWF A2-ΔCC and A2-VicCC. (A) Purified VWF A2-VicCC was detected on a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel (lane 1). VWF A2-ΔCC was incubated with maleimide-PEG2-biotin (MBP) without (NR, lane 2), and with prior reduction by incubation with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) agarose beads (lane 3, R). Afterward, reactions were quenched with reduced L-glutathione. Biotin-labeled sulfhydryl groups were detected on Western blot using peroxidase-labeled streptavidin. The same samples were also detected on Western blot using c-myc monoclonal antibody to control for equal loading (lanes 4 and 5). (B) Recombinant ADAMTS13 (2nM) was preincubated with 5mM CaCl2 for 1 hour at 37°C. Then, 2μM VWF A2-ΔCC or A2-VicCC (NR) variant and 1.5M urea were added and samples were taken at the indicated time points (0-3 hours). Reactions were stopped by the addition of 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. We simultaneously also performed this assay using A2-VicCC that was reduced with 10mM DTT, then carboxymethylated with 20mM iodoacetic acid, and afterward quenched with 40mM DTT and extensively dialyzed before use in the activity assay (A2-VicCC R). Samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. On proteolysis by ADAMTS13, the N- and C-terminal cleavage fragments became apparent. The experiment was performed 3 times; a representative result is shown. (C) Binding of serial dilutions of purified ADAMTS13 to 50nM immobilized VWF A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC (NR) and reduced and carboxymethylated VWF A2-VicCC (R). The assay was performed in the presence of 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to prevent proteolysis. Bound ADAMTS13 was detected using biotinylated anti–TSR2-4 polyclonal antibodies, followed by streptavidin-peroxidase. Binding curves were generated using GraphPad Prism software, fitting the data to the one-binding site equation. (D) Purified ADAMTS13 (30nM) was preincubated for 1 hour with 0 to 600nM soluble A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC (NR), and reduced and carboxymethylated A2-VicCC (R). After preincubation, the mixture was added to wells with 50nM immobilized VWF A2-ΔCC, and ADAMTS13 was allowed to bind for 1 hour in the presence of the soluble VWF A2 variants. Bound ADAMTS13 was then detected as in panel C. Curves were fitted to a one-site competition model using GraphPad Prism software. (E) CD spectra of VWF A2-ΔCC, A2-VicCC, A2-CC1, and A2-CC2 at 20°C. Measurements were taken over 190 to 260 nm, at a 0.5-nm interval, bandwidth 1 nm, 1 second per data point. Data were converted to mean residue molar ellipticity, and averages of 6 to 12 measurements are shown. (F) Change in mean residue molar ellipticity on increase of temperature at 5°C intervals from 20°C to 80°C, as determined at 222 nm. Averages of 5 measurements are shown. Curves were plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Under denaturing conditions (1.5M urea), proteolysis of A2-VicCC by ADAMTS13 was appreciably slower than that of A2-ΔCC (Figure 1B). The susceptibility of A2-VicCC to proteolysis may be somewhat overestimated because of the small proportion of A2-VicCC in which vicinal disulfide bonds had not formed. Reduction and carboxymethylation of the cysteines in A2-VicCC increased the rate of proteolysis to that of A2-ΔCC, demonstrating that the disulfide bond rather than the 2 cysteines mediate the stabilizing effect. In parallel, we also studied variants VWF A2-CC1 and A2-CC2, each containing a disulfide bond in homologous positions to those found in VWF A1 and A3 (supplemental Figure 1). These A2 variants were indeed stabilized against unfolding, as seen by their complete resistance to proteolysis by ADAMTS13 (supplemental Figure 2).

The effect of the C1669/C1670 vicinal disulfide bond on VWF A2 domain binding of to ADAMTS13

The α6-helix immediately adjacent to the vicinal cysteines (E1660-R1668) contains a high-affinity binding exosite for the ADAMTS13 spacer domain.14-16 Binding of ADAMTS13 to immobilized A2-ΔCC and A2-VicCC was equally efficient (Figure 1C), in contrast to the low binding observed using immobilized A2-CC1 and A2-CC2 variants (supplemental Figure 2). It appears, therefore, that A2-VicCC unfolds on immobilization, allowing access of ADAMTS13 to the C-terminal-binding exosite. However, when we studied binding to ADAMTS13 in solution, we found that the presence of the vicinal disulfide bond largely prevented A2-VicCC from competing with the binding of ADAMTS13 to immobilized A2-ΔCC (Figure 1D). On disulfide bond reduction, however, A2-VicCC efficiently competed with ADAMTS13 binding. Recent molecular dynamics simulations17,18 and studies using optical tweezers19 have suggested that the A2 domain unfolds progressively from its C-terminus; the α6-helix is peeled off first, followed by the β6 and α5-helix.17,18 We propose that the vicinal disulfide bond primarily influences the initial uncoupling of the α6-helix and therefore directly modulates the exposure of the high-affinity ADAMTS13-binding site. Thereafter, a second unfolding step is required for the detachment of the β5 and α4-less loop and exposure of the cleavage site in the β4 strand, as A2-ΔCC is cleaved inefficiently without denaturant.12

The effect of the vicinal disulfide bond on global secondary structure and thermodynamic stability

The influence of the vicinal disulfide bond on A2 domain secondary structure was examined by CD. The spectra of A2-CC1, A2-CC2, and A2-VicCC fragments were essentially indistinguishable from A2-ΔCC (Figure 1E), suggesting that the global secondary structure is unaffected by disulfide bonds. We then used temperature-induced unfolding to examine domain stability (Figure 1F). A2-ΔCC unfolded with a transition temperature of 53.7°C plus or minus 0.3°C, whereas A2-VicCC, A2-CC1, and A2-CC2 were appreciably more resistant to temperature-induced conformational changes (transition temperatures of 61.5°C ± 0.4°C, 66.3°C ± 0.3°C, and 65.2°C ± 0.3°C, respectively). Notably, when the samples were rapidly cooled to 20°C after heating, the CD signals returned to their initial values, suggesting that after unfolding, the A2 domain naturally refolds to its native conformation (not shown).

Studies on full-length VWF

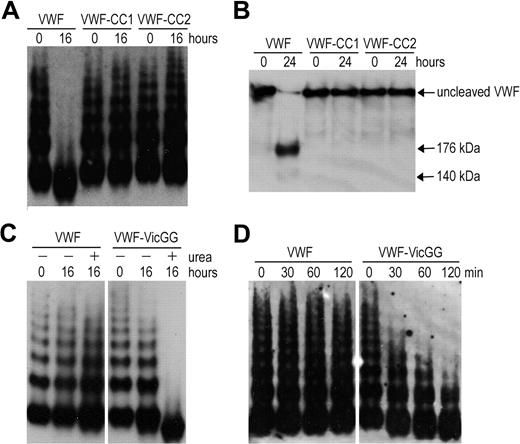

To explore VWF A2 domain stabilization in full-length VWF, we introduced the mutations N1493C/C1669G (VWF-CC1) and N1493C/C1670G (VWF-CC2). The multimers of VWF-CC1 and VWF-CC2 were completely resistant to proteolysis by ADAMTS13 under denaturing conditions, whereas wild-type VWF (containing the vicinal disulfide bond) was cleaved (Figure 2A). Analysis of reduced samples ensured that cleavage of the mutants was not masked by disulfide bonds between cleavage products (Figure 2B). Thus, both mutants behave in a similar way as the recently reported VWF mutant (N1493C/C1670S).18 We then mutated C1669 and C1670 (VWF-VicGG) and examined its susceptibility to proteolysis by ADAMTS13. Proteolysis of VWF-VicGG was very efficient; some proteolysis of this variant even occurred in the absence of urea (Figure 2C), suggesting that without the vicinal cysteines the VWF A2 domain more readily unfolds. A time-course experiment using a lower concentration of ADAMTS13 further confirmed this finding (Figure 2D). Together, our results demonstrate the important contribution of the vicinal disulfide bond to VWF A2 domain function.

Proteolysis of full-length VWF variants by ADAMTS13. (A) VWF, VWF-CC1, and VWF-CC2 with introduced disulfide bonds were predenatured in the presence of 2.5M urea for 1 hour at 37°C to induce unfolding. ADAMTS13 was preincubated with 5mM CaCl2. After preincubation, both mixtures were combined and contained 0.5 μg/mL VWF and 20nM ADAMTS13. After 0 and 16 hours of incubation at 37°C, samples were taken and reactions stopped by the addition of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Samples were separated at 1.4% SDS-agarose gel and VWF multimers were detected using polyclonal anti-VWF antibody. (B) Same as in panel A, but samples were incubated for 0 to 24 hours, reduced with 5% β-mercaptoethanol for 30 minutes at 60°C, and separated on 3% to 8% acetate gel. (C) Proteolysis of VWF and VWF in which the vicinal cysteines C1669 and C1670 were changed to glycine (VWF-VicGG). Same as in panel A, but coincubation with 2nM ADAMTS13 for 0 to 16 hours in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1.5M urea. (D) Same as in panel A, but using shorter incubation of 0 to 120 minutes in the presence of 2nM ADAMTS13 and 1.5M urea.

Proteolysis of full-length VWF variants by ADAMTS13. (A) VWF, VWF-CC1, and VWF-CC2 with introduced disulfide bonds were predenatured in the presence of 2.5M urea for 1 hour at 37°C to induce unfolding. ADAMTS13 was preincubated with 5mM CaCl2. After preincubation, both mixtures were combined and contained 0.5 μg/mL VWF and 20nM ADAMTS13. After 0 and 16 hours of incubation at 37°C, samples were taken and reactions stopped by the addition of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Samples were separated at 1.4% SDS-agarose gel and VWF multimers were detected using polyclonal anti-VWF antibody. (B) Same as in panel A, but samples were incubated for 0 to 24 hours, reduced with 5% β-mercaptoethanol for 30 minutes at 60°C, and separated on 3% to 8% acetate gel. (C) Proteolysis of VWF and VWF in which the vicinal cysteines C1669 and C1670 were changed to glycine (VWF-VicGG). Same as in panel A, but coincubation with 2nM ADAMTS13 for 0 to 16 hours in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1.5M urea. (D) Same as in panel A, but using shorter incubation of 0 to 120 minutes in the presence of 2nM ADAMTS13 and 1.5M urea.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof K. Drickamer for expert technical advice on CD measurements and data analysis.

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (grant RG/02/008, now RG/06/007). The Chirascan was purchased by a grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Authorship

Contribution: B.M.L. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed results, and wrote the paper; L.Y.N.W. performed experiments; and J.E., D.A.L., and J.T.B.C. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brenda M. Luken, Department of Haematology, Imperial College London, Du Cane Rd, London, W12 0NN, United Kingdom; e-mail: b.luken@imperial.ac.uk.