Abstract

Pompe disease (acid α-glucosidase deficiency) is a lysosomal glycogen storage disorder characterized in its most severe early-onset form by rapidly progressive muscle weakness and mortality within the first year of life due to cardiac and respiratory failure. Enzyme replacement therapy prolongs the life of affected infants and supports the condition of older children and adults but entails lifelong treatment and can be counteracted by immune responses to the recombinant enzyme. We have explored the potential of lentiviral vector–mediated expression of human acid α-glucosidase in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in a Pompe mouse model. After mild conditioning, transplantation of genetically engineered HSCs resulted in stable chimerism of approximately 35% hematopoietic cells that overexpress acid α-glucosidase and in major clearance of glycogen in heart, diaphragm, spleen, and liver. Cardiac remodeling was reversed, and respiratory function, skeletal muscle strength, and motor performance improved. Overexpression of acid α-glucosidase did not affect overall hematopoietic cell function and led to immune tolerance as shown by challenge with the human recombinant protein. On the basis of the prominent and sustained therapeutic efficacy without adverse events in mice we conclude that ex vivo HSC gene therapy is a treatment option worthwhile to pursue.

Introduction

Glycogenosis type II (Pompe disease, acid maltase deficiency; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man no. 232300) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder caused by acid α-glucosidase (GAA) deficiency. The disease is characterized by glycogen storage in liver, spleen, kidney, brain, and endothelial cells and most prominently in skeletal, heart, and smooth muscles. Symptoms arise from muscular weakness and wasting. Infants with complete enzyme deficiency present shortly after birth, lose all muscle strength within 8 months, and succumb to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and respiratory failure in the first year of life.1 Children and adults with residual GAA activity show a more protracted course and may become wheelchair bound, dependent on artificial ventilation, and have a shortened life expectancy. Presently, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) based on intravenous infusion of recombinant human α-glucosidase, taken up by mannose 6-phosphate receptor mediated endocytosis,2,3 is a major therapeutic advance that prolongs the life of affected infants but does not guarantee long-term symptom-free survival, requires biweekly administration, and may induce immune responses to the recombinant protein.

As an alternative to ERT, in vivo gene therapy mediated by adenoviral vectors and adeno-associated virus vectors (AAVs) has been investigated in a mouse model of Pompe disease.4-6 However, long-term efficacy can be significantly hampered by antibody formation,7,8 and adverse immune responses to the vector has been observed after adenoviral and AAV gene therapy in patients.9,10

For treatment of patients with other lysosomal enzyme deficiencies, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation has been proposed.11 HSC transplantation proved effective in ameliorating the neurologic symptoms in murine globoid cell leukodystrophy and human patients12,13 as well as in mucopolysaccharidosis I (Hurler syndrome).14,15 Other lysosomal storage disorders such as metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) may require higher enzyme levels than provided by HSC transplantation; lentiviral (LV) vector–mediated overexpression of aryl-sulfatase A in HSCs effectively reversed the neuropathologic phenotype in the mouse model.16 In addition, LV-mediated clinical gene therapy in trial phase of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy halted progressive cerebral demyelination in 2 patients.17 Recently, HSC transplantation was shown to promote immune tolerance to ERT in the Pompe mouse model.18 The use of gene-modified autologous HSCs also overcomes the profound conditioning and immune barriers associated with allogeneic transplantation.

The few attempts of HSC transplantation for Pompe disease have not met with success.19 GAA levels, if any, are low in hematopoietic cells in mice,18 and allogeneic transplantation is not an obvious treatment. Therefore, high-level vector–driven ectopic expression of the enzyme in hematopoietic cells would be required to accomplish efficacy. We tested the hypothesis that ex vivo LV vector mediated overexpression of GAA in a relatively small number of HSCs would be beneficial after transplantation in preventing or reversing clinical symptoms of Pompe disease. We deliberately chose a competitive repopulation strategy, in which the transduced stem cells compete with residual endogenous and nontransduced cells in the transplant, resulting in stable partial chimerism with the main hematopoietic system untouched by genetic modification.

Methods

Animals

Normal FVB and congenic Gaa−/− knockout mice were obtained as described.20 The animals do not produce Gaa mRNA, have a complete deficiency of GAA, and parallel the human infantile-onset Pompe disease by pathologic criteria and clinical symptoms (ie, heart and skeletal muscle weakness).20,21 The animal experiments were reviewed and approved by an ethical committee of Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, in accordance with legislation in The Netherlands.

Cell culture

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for titration of LV vectors were isolated from bone marrow (BM) of Gaa−/− mice by flushing femurs. MSCs were allowed to attach overnight in 10-cm2 tissue culture dishes, and the remaining hematopoietic cells were removed by washing. MSCs were cultured in a mixture of 48% Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with low glucose (Gibco), 32% MCDB 201 medium (Sigma), and 20% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) with the addition of penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2mM l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), and penicillin and streptomycin.

Construction of LV vector plasmids

The human GAA (hGAA) cDNA was excised with EcoRI and SphI from plasmid pSHAG222 and cloned in the pSUPER vector (Oligoengine) containing a polylinker with sequential AgeI, EcoRI, SphI, and XbaI restriction sites (pSli). The pSli-GAA plasmid was then digested by AgeI, XbaI and subcloned in a LV vector backbone with sequential AgeI, NheI, SwaI restriction sites. The final plasmid was constructed by removal of the hGAA cDNA containing AgeI-SwaI fragment to replace the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) of pRRL.PPT.SF.EGFP.WPRE4*.SIN (LV-SF-GFP, kindly provided by Axel Schambach, Hannover Medical School, Germany) to obtain the LV vector LV-SF-GAA. The vectors contain the HIV central polypurine tract and the spleen focus-forming (SF) virus promoter to drive transgene expression as well as modified woodchuck posttranslational regulatory element (WPRE4*) with 4 deleted ATG sites and a large deletion of the Woodchuck hepatitis X-protein sequence.23

Production of LV vectors

Third-generation self-inactivating LV vectors were produced by standard calcium phosphate transfection of HEK 293T cells with the plasmids pMDL-g/pRRE, pMD2-VSVg and pRSV-Rev.24,25 Titers of LV-SF-GFP were determined by end-point titration on mouse Gaa−/− MSCs by flow cytometry. LV-SF-GAA vector titers were determined by counting immunofluorescence-stained MSCs (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). For in vivo studies LV vectors were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (2 hours, 50 000g rpm, 4°C) and stored until use.

LV HSC transduction

Donor BM was extracted from femurs and tibias of 8- to 12-week-old male Gaa−/− mice, and hematopoietic progenitors were purified by lineage depletion (Lin−) according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD). After enrichment, Lin− cells were transduced by LV-SF-GFP or LV-SF-GAA LV vectors overnight at a cell density of 106 cells/mL and a multiplicity of infection of 9 to 10 in serum-free modified Dulbecco medium as described,26 supplemented with growth factors (murine–stem cell factor, 100 ng/mL; human FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 murine, 50 ng/mL; ligand thrombopoietin, 10 ng/mL). The following day, 5 × 105 transduced Lin− cells were injected in the tail vein of 8- to 12-week-old female Gaa−/− recipients subjected to a sublethal total body radiation dose of 6 Gy.

Tissue preparation

At termination of experiments, mice were deprived of food overnight, anesthetized with isoflurane, and killed by transcardial perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The following tissues were collected: heart, diaphragm, stomach, uterus, quadriceps femoris (QF), spleen, lung, liver, kidney, and brain. For assay of GAA activity, tissue aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Tissue aliquots for periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining were fixed in 1% formaldehyde + 4% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1% cacodylate, pH 7.3. PAS staining was performed as described,20 and tissue slides were quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence staining

MSCs plated on glass coverslips were LV-SF-GFP or LV-SF-GAA transduced and fixed 5 days later with ice-cold methanol/acetone (4:1) for 10 minutes. Similarly, BM cells were allowed to attach onto Retronectin (Takara Inc) coated coverslips for 4 hours and fixed. The cells were blocked by incubation in 10% FCS in PBS with 0.05% Tween for 30 minutes and subsequently incubated with anti-GAA antibody, raised in rabbits against human placental enzyme but also recognizing the mouse enzyme,20 at 1:100 dilution in blocking solution (2% FCS/PBS/0.05% Tween), followed by 1 hour with goat anti–rabbit–Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; Invitrogen). Finally, stained cells were embedded in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) containing DAPI (4′-6′-diamidine-2-phenylindole). The slides were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMRXA) with attached camera (Leica DFC 350FX) and analyzed with Leica FW4000 Version 1.2.1.

Enzymatic assays

All tissues were homogenized in water by sonication (MSE sonifier) on ice until completely lysed (medium level, amplitude 5 μm). The GAA activity was determined by fluorometry, according to a protocol based on 4-methylumbelliferyl α-D-glucopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich).27 Plasma was collected in lithium heparin-coated blood-sampling tubes (BD Microtainer) with gel and was centrifuged immediately after collection to separate plasma from cells. GAA was extracted from the plasma samples with anti-GAA antibodies in combination with protein A–sepharose beads before measurement of enzyme activity to avoid nonspecific activity of nonspecific glycosidases.

Glycogen content was determined as described.2 The resulting glucose was measured after conversion by glucose-oxidase and reaction with 2,2′-azino-di-(ethyl-benzthiazolinsulfonate). The GAA activity and the glycogen content were both calculated on the basis of protein content of the homogenates, which was measured with the use of the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce).

Western blotting

Protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto nitrocellulose filters, incubated with anti–α-glucosidase antiserum (1250× diluted), and the complex of enzyme and antibody was visualized with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences) with the use of goat anti–rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to IRDye 800 CW (1:10 000) as secondary antibody.

Immunization of mice and anti–human GAA enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay

Wild-type (WT), Gaa−/− LV-SF-GFP– and LV-SF-GAA–treated mice were injected with human recombinant GAA [Myozyme (alglucosidase alfa); 20 mg/kg] together with Freund adjuvant and 2 weeks later rechallenged with human recombinant GAA. Plasma was collected before and 2 weeks after each injection.

For anti–human GAA enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA), human GAA and GFP were produced in HEK 293T cells by LV transduction, confirmed by enzymatic assay and GFP by fluorescence microscopy, respectively. ELISA plates (Nunc) were coated overnight with 5 μg/mL cellular lysate in PBS, pH 7.4, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, washed, and incubated with serial dilutions of plasma from WT, LV-SF-GFP–, or LV-SF-GAA–treated mice. After washing, mouse immunoglobulins were detected with anti–mouse IgG peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) and 3.3′, 5.5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). ELISAs were performed in triplicate with the same plasma samples applied to GAA- and GFP-coated plates.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction of LV integrations

The DNA Nucleospin kit (Bioke) was used to extract DNA from BM and spleen cells to determine the copy number per cell by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR) in an ABI PRISM 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems).28 Reactions were performed with 50 ng of genomic DNA with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with the following primer set: HIV-U3 forward primer, 5′-CTGGAAGGGCTAATTCACTC-3′, and HIV reverse primer, 5′-GGTTTCCCTTTCGCTTTCAG-3′. To asses chimerism, primers specific for the Sry locus on the mouse Y chromosome were developed: forward primer, 5′-CATCGGAGGGCTAAAGTGTCAC-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-TGGCATGTGGGTTCCTGTCC-3′. The samples were normalized for mouse Gapdh with the following primer set: forward primer, 5′-CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGAC-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-TGACCTTGCCCACAGCCTTG-3′. A standard line for the LV integrations was determined from sorted mouse 3T3 cells transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 0.06. Samples were analyzed with SDS2.2.2 software (Applied Biosystems).

Echography and hemodynamics

Mice were sedated with 4% isoflurane, intubated,29 and ventilated with a mixture of O2 and N2O (1/2; vol/vol) with a pressure-controlled ventilator (CWE, SAR-830/P) to which 2.5% isoflurane was added for anesthesia. Ventilation rate was set at 90 strokes/min with a peak inspiration pressure of 18 cm H2O and a positive end expiration pressure of 4 cm H2O. The mice were placed on a heating pad to maintain body temperature at 37°C.

In vivo transthoracic echocardiography of the left ventricle was performed with the ALOKA echo device (Pro Sound, SSD-4000) with a 13-MHz linear interfaced array transducer.29 M-mode echocardiograms were captured from short-axis 2-dimensional views of the left ventricle at midpapillary level with simultaneous electrocardiogram. Left ventricular lumen diameters at end diastole and end systole as well as wall thickness were measured from the M-mode images with the use of SigmaScan Pro 5 Image Analysis software (SPSS Inc). Three cardiac cycles for each animal were analyzed by a blinded observer. Fractional shortening was calculated with the following equation: [(ventricular lumen diameter at end diastole − ventricular lumen diameter at end systole)/ventricular lumen diameter at end diastole × 100%]. After echocardiography, a 1.4F Millar Instruments pressure transducer catheter (SPR-671; Millar Instruments; calibrated before each experiment with a mercury manometer) was inserted in the right carotid artery and advanced into the left ventricle for measuring left ventricular pressure and heart rate. From the left ventricular pressure signal, we obtained the rate of rise of left ventricular pressure at left ventricular pressure of 30 mm Hg (dP/dtP30), as a measure of left ventricular systolic function, the time constant of left ventricular relaxation (Tau), as well as the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure were obtained as parameters of diastolic function.29 At the conclusion of each experiment, the heart was excised, the atria were removed, and the right ventricle and left ventricle (including septum) were separated and mass determined.

Hemodynamic data were recorded and digitized with an online 4-channel data acquisition program (ATCODAS; Dataq Instruments) for later analysis with a program written in MatLab (MathWorks). A minimum of 10 consecutive beats were selected for analysis.

Ventilatory function

Airway function was tested by whole-body plethysmography (Buxco Electronics) comparable with a setting used to assess airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with asthma to metacholine. This test can be influenced by muscular weakness and exhaustion. Mice were exposed to nebulized physiologic saline for 3 minutes and then to increasing concentrations of nebulized metacholine in PBS (1.56-50 mg/mL) with the use of an ultrasonic nebulizer. Measurements were obtained for 3 minutes after the completion of each nebulization. The following parameters were measured: the average peak inspiratory flow (PIF; mL/sec), tidal volume (TV; mL/breath), and frequency of breathing (breaths/min).

Motor performance

To determine skeletal muscle strength, grip measurement was performed with the Bioseb Grip Strength test. The mice were held by the tail and pulled backward over the grid with all limbs to measure the magnitude of the peak force (in mN). Three single pulls per mouse were averaged. All data points were collected over time in mice older than 150 days, and averages per mouse were used to compare treatment groups.

Motor muscle tasks were performed with the accelerating rotarod (from 4 to 40 rpm in 5 minutes; model 7650, Ugo Basile Biologic Research apparatus). Mice were given 2 trials to adjust to the apparatus, followed by 3 runs with intervals of 5 minutes, which were averaged.

The running performance was measured by a computerized system connected to running wheels.30 The distance run was calculated by multiplying the revolutions with the circumference of the wheels.

Peripheral blood counts, phenotyping, and in vitro clonogenic progenitor assays

Blood cell counts were measured with a Vet ABC hematology analyzer (Scil Animal Care Company GmbH). Peripheral blood (PB), BM, and spleen cells were stained with antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, IgM, CD11b, Gr-1, Sca-1, c-Kit directly conjugated to PE or APC (All BD Biosciences) and measured by flow cytometry. In vitro clonogenic assays were performed as described.26,31-34

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 11 (SPSS Inc). Significance of differences was determined by 1-way analysis of variance or Mann-Whitney U test for comparing 2 groups. For repeated measurements 2-way analysis of variance was used to determine differences between groups (for P values, see supplemental data). Significance of a difference was assumed if the P value was less than .05. All error bars represent SEM.

Results

Ex vivo transduction of BM cells leads to high levels of GAA activity in Gaa−/− mice

Gaa−/− recipients of LV-SF-GFP–transduced Lin− male BM cells displayed long-term expression of GFP in blood as measured by flow cytometry (data not shown). LV-SF-GAA–treated mice displayed high levels of GAA activity in leukocytes (average of all measured samples is 71.1 ± 47.3 nmol/h/mg protein; N = 77; Figure 1A) for an observation time of 1.5 year, 35-fold higher than background values attributable to other glycosidases measured in LV-SF-GFP mice (2.0 ± 1.7 nmol/h/mg protein; N = 81), and also higher than in 8-month-old WT mice (Table 1; Figure 1A). GAA activity at 8 months in WT mice was not different from background levels detected in Gaa−/− mice. This shows that GAA levels in leukocytes are hardly detectable (Figure 1A; Table 1).

In vivo LV expression of human GAA. (A) Gaa−/− mice received a transplant with 5 × 105 Lin− cells transduced with the therapeutic vector (LV-SF-GAA) at a multiplicity of infection of 9 to 10. The GAA activity in peripheral leukocytes of a total of 32 LV-SF-GAA–treated mice was measured, starting from day 29 after transplantation to the last data point at day 549 (n = 4). Fifteen Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP served as negative controls. The leukocyte α-glucosidase levels (3.4 ± 1.3 nmol/h/mg) of congenic FVB mice (n = 6) are indicated by the dotted line. (B) Illustration of GAA expression and lysosomal localization in BM cells of a WT, a Gaa−/− mouse, and a Gaa−/− mouse that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA–transduced HSCs harvested 8 months after transplantation [blue nuclear DAPI (4′-6′-diamidine-2-phenylindole) stain and green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 immunostaining for GAA protein; original magnification ×1000]. (C) At 8 months after transplantation, Western blot analysis of GAA expression in BM and spleen (SPL) shows a known pattern of 95-kDa (intermediate species) and 76-kDa (mature species) forms of human GAA, reflecting GAA synthesis, posttranslational modification, maturation, and lysosomal localization.22 Mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP do not express human GAA, whereas the level of GAA expression in WT animals is too low to detect. A dilution of recombinant human GAA (rhGAA) of 110 kDa serves as a marker. (D) Plasma GAA enzyme levels. Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA showed variable but detectable GAA enzyme levels in plasma compared with background activity (BL) detected in Gaa−/− mice. Low activity levels were also detected in WT mice. Numbers in the figure that accompany the plasma data represent GAA activity (nmol/h/mg) in leukocytes. (E) Reconstitution of GAA activity in Gaa−/− mice. GAA activity in tissues of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA and age-matched WT mice at 10 months of age (n = 3-6 mice for all tissues, except for LV-SF-GFP brain). *Significant difference (P < .05) of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA compared with both WT and LV-SF-GFP mice. †Significant difference (P < .05) between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP but not between LV-SF-GAA and WT mice. (F) Tolerance to rhGAA in Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA. Both WT (n = 2) and LV-SF-GFP–treated Gaa−/− (n = 2) mice responded by the generation of anti–human GAA antibodies after a first injection of rhGAA (Myozyme, 20 mg/kg) with Freund adjuvant (rhGAA + A) followed by a second injection of rhGAA without adjuvant 2 weeks later. LV-SF-GAA–treated Gaa−/− mice (n = 13) did not respond to the challenge with rhGAA. (G) The percentage of reconstituted male cells in BM of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA female recipients (chimerism) was determined by Y chromosome Sry q-PCR and corrected for overall genomic DNA by Gapdh q-PCR (n = 6). (H) Copy number of LV vector integrations. Q-PCR was used to determine the average copy number in male BM cells (n = 6). Horizontal lines in panels G and H represent mean value.

In vivo LV expression of human GAA. (A) Gaa−/− mice received a transplant with 5 × 105 Lin− cells transduced with the therapeutic vector (LV-SF-GAA) at a multiplicity of infection of 9 to 10. The GAA activity in peripheral leukocytes of a total of 32 LV-SF-GAA–treated mice was measured, starting from day 29 after transplantation to the last data point at day 549 (n = 4). Fifteen Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP served as negative controls. The leukocyte α-glucosidase levels (3.4 ± 1.3 nmol/h/mg) of congenic FVB mice (n = 6) are indicated by the dotted line. (B) Illustration of GAA expression and lysosomal localization in BM cells of a WT, a Gaa−/− mouse, and a Gaa−/− mouse that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA–transduced HSCs harvested 8 months after transplantation [blue nuclear DAPI (4′-6′-diamidine-2-phenylindole) stain and green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 immunostaining for GAA protein; original magnification ×1000]. (C) At 8 months after transplantation, Western blot analysis of GAA expression in BM and spleen (SPL) shows a known pattern of 95-kDa (intermediate species) and 76-kDa (mature species) forms of human GAA, reflecting GAA synthesis, posttranslational modification, maturation, and lysosomal localization.22 Mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP do not express human GAA, whereas the level of GAA expression in WT animals is too low to detect. A dilution of recombinant human GAA (rhGAA) of 110 kDa serves as a marker. (D) Plasma GAA enzyme levels. Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA showed variable but detectable GAA enzyme levels in plasma compared with background activity (BL) detected in Gaa−/− mice. Low activity levels were also detected in WT mice. Numbers in the figure that accompany the plasma data represent GAA activity (nmol/h/mg) in leukocytes. (E) Reconstitution of GAA activity in Gaa−/− mice. GAA activity in tissues of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA and age-matched WT mice at 10 months of age (n = 3-6 mice for all tissues, except for LV-SF-GFP brain). *Significant difference (P < .05) of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA compared with both WT and LV-SF-GFP mice. †Significant difference (P < .05) between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP but not between LV-SF-GAA and WT mice. (F) Tolerance to rhGAA in Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA. Both WT (n = 2) and LV-SF-GFP–treated Gaa−/− (n = 2) mice responded by the generation of anti–human GAA antibodies after a first injection of rhGAA (Myozyme, 20 mg/kg) with Freund adjuvant (rhGAA + A) followed by a second injection of rhGAA without adjuvant 2 weeks later. LV-SF-GAA–treated Gaa−/− mice (n = 13) did not respond to the challenge with rhGAA. (G) The percentage of reconstituted male cells in BM of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA female recipients (chimerism) was determined by Y chromosome Sry q-PCR and corrected for overall genomic DNA by Gapdh q-PCR (n = 6). (H) Copy number of LV vector integrations. Q-PCR was used to determine the average copy number in male BM cells (n = 6). Horizontal lines in panels G and H represent mean value.

High GAA activity was also detected in BM and spleen cells of LV-SF-GAA–treated mice 8 months and 1.5 year after treatment (Table 1), respectively, with levels in WT mice being approximately 2.5% of levels in LV-SF-GAA–treated mice. GAA protein in BM cells was confirmed by immunofluorescence staining in LV-SF-GAA–treated mice (Figure 1B). In addition, molecular species of intermediate (95 kDa) and mature (76 kDa) forms of GAA were detected by Western blotting after LV-SF-GAA treatment at 10 months of age (Figure 1C). GAA expression in WT mice could not be detected by Western blotting, consistent with the low levels of activity in WT leukocytes but was clearly enhanced in plasma of LV-SF-GAA mice (Figure 1D).

The long-term expression of GAA in hematopoietic cells resulted in reconstitution of activity in target tissues (Figure 1E), that is, heart, smooth muscle–containing tissues (diaphragm, stomach, and uterus), in skeletal muscle measured in the QF, and in lung and liver, but not in brain tissue. The data show that sublethal irradiation and transplantation of a clinically feasible number of hematopoietic cells results in stable ectopic production and high levels of human α-glucosidase in affected target tissues. Notably, challenging the mice with the recombinant human enzyme with Freund adjuvant showed that expression in hematopoietic cells resulted in immune tolerance to the transgene product (Figure 1F).

Hematopoietic chimerism and transgene copy number per cell

Chimerism, defined as the contribution of transplanted male cells to overall blood cell production in BM, is shown in Figure 1G. The percentage of Y chromosome–positive BM cells was on average 38 ± 15 for LV-SF-GFP–treated Gaa−/− mice (N = 6) and 34 ± 16 for LV-SF-GAA–treated mice (N = 6). The percentage of GFP+ cells was 36 ± 12 in BM, and similar levels were observed in spleen and PB (N = 7), consistent with the subablative regimen used. Transduction efficiencies by measurement of GFP expression in vitro were greater than 70%; thus, most transplanted donor cells contained the integrated LV vector.

Q-PCR was performed to determine the LV copy number per cell in BM of LV-SF-GFP– and LV-SF-GAA–treated mice (Figure 1H). The percentage of chimerism in BM of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA mice was used to calculate the number of integrations per transduced cell (LV vector copies/fraction male BM genomes of total BM genomic DNA). LV-SF-GAA–treated mice were corrected with the same formula, which resulted in similar copy numbers per cell in LV-SF-GAA– and LV-SF-GFP–treated mice of 7.3 ± 3.6 and 6.1 ± 3.5, respectively.

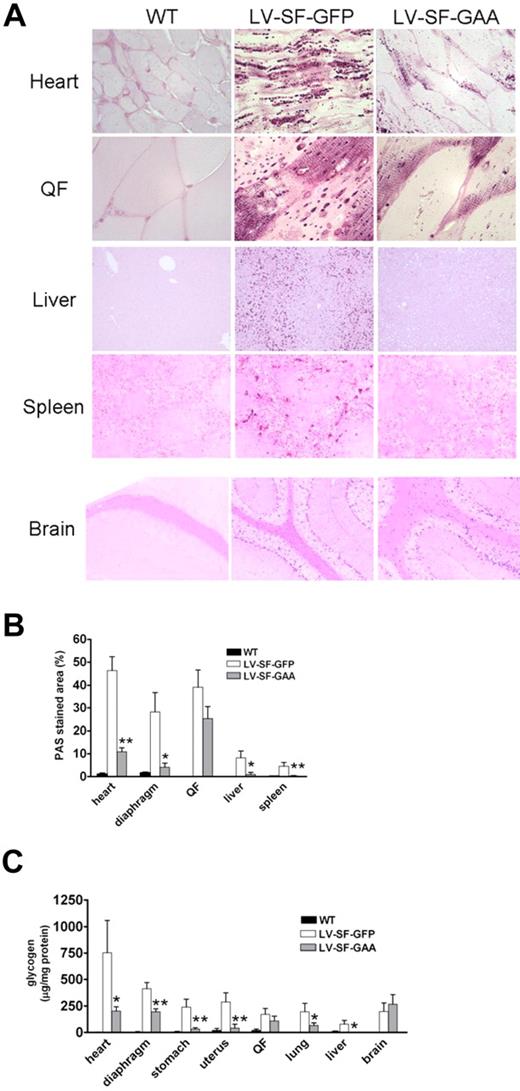

Transplantation of GAA-expressing HSCs reduces glycogen deposition

To evaluate the effect of overexpressed GAA, we examined the tissues by histology and quantitative PAS staining. LV-SF-GAA–treated Gaa−/− mice had a significant reduction in glycogen storage compared with LV-SF-GFP–treated Gaa−/− mice in various tissues, ie, heart, diaphragm, liver, and spleen (Figure 2). Importantly, glycogen assay confirmed the robust glycogen reduction in heart of LV-SF-GAA–treated mice, as well as in lungs and liver, and in tissues that contained smooth muscle, such as diaphragm, stomach, and uterus, with a limited reduction in QF, representing skeletal muscles, and none in brain tissue (both cortex and cerebellum).

Glycogen deposition in WT and Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA. (A) PAS staining (dark purple stain) shows glycogen deposition in heart, QF, spleen, liver, and brain (cortex) of 8-month-old mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP. Clearance of glycogen is observed in liver and spleen of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA. Reduction of glycogen storage is observed in heart and skeletal muscle. Brain does not respond. Heart and QF, original magnification ×1000; liver, spleen, and brain original magnification ×125. (B) Quantification of the PAS staining by ImageJ shows a reduction of glycogen storage in heart, diaphragm, liver, and spleen but only marginal reduction in QF at 8 months after transplantation. PAS stained area as the percentage of total area is presented for LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA groups (n = 4-6); *P < .05 and **P < .01 indicate a significant difference between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP. (C) Enzymatic quantification of the glycogen deposition in tissues at 8 months after transplantation. The figure shows a reduction of glycogen in all tissues tested except brain (n = 4-11); *P < .05 and **P < .01 indicate a significant difference between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP.

Glycogen deposition in WT and Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA. (A) PAS staining (dark purple stain) shows glycogen deposition in heart, QF, spleen, liver, and brain (cortex) of 8-month-old mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP. Clearance of glycogen is observed in liver and spleen of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA. Reduction of glycogen storage is observed in heart and skeletal muscle. Brain does not respond. Heart and QF, original magnification ×1000; liver, spleen, and brain original magnification ×125. (B) Quantification of the PAS staining by ImageJ shows a reduction of glycogen storage in heart, diaphragm, liver, and spleen but only marginal reduction in QF at 8 months after transplantation. PAS stained area as the percentage of total area is presented for LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA groups (n = 4-6); *P < .05 and **P < .01 indicate a significant difference between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP. (C) Enzymatic quantification of the glycogen deposition in tissues at 8 months after transplantation. The figure shows a reduction of glycogen in all tissues tested except brain (n = 4-11); *P < .05 and **P < .01 indicate a significant difference between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP.

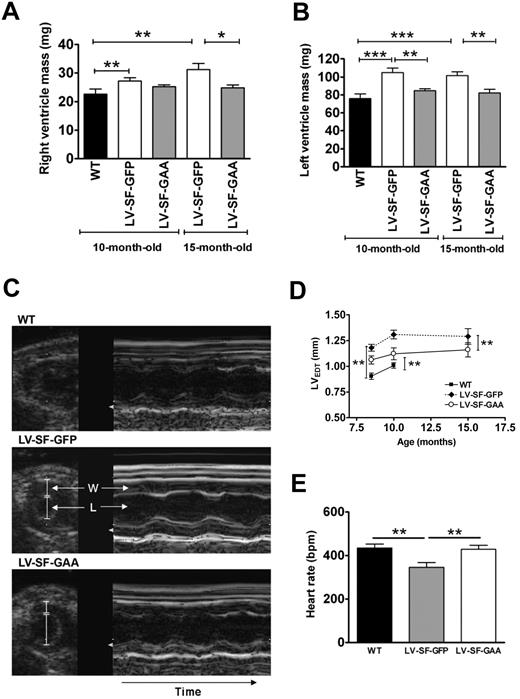

Transplantation of GAA-expressing HSCs reverses cardiac remodeling

Major differences in heart geometry between WT, LV-SF-GFP– and LV-SF-GAA–treated mice are depicted in Figure 3. In agreement with previous observations,35 Gaa deficiency in LV-SF-GFP mice results in an elevated mass of both the right and the left ventricles at 10 and 15 months relative to those in WT mice (Figure 3A-B), resulting from an increased wall thickness (Figure 3C-D), whereas left ventricular lumen diameter was not significantly affected (not shown). Mean aortic pressure was not significantly affected either (99 ± 3 mm Hg vs 89 ± 4 mm Hg), but heart rate was significantly reduced in LV-SF-GFP mice compared with WT mice (P < .01; Figure 3E). Global left ventricular pump function was still maintained in LV-SF-GFP mice compared with WT mice, as evidenced by normal levels of indexes of systolic function, including left ventricular dP/dtP30 (7380 ± 660 mm Hg/s vs 7930 ± 990 mm Hg/s) and fractional shortening (46% ± 2% vs 43% ± 1%), as well as near normal levels of indexes of diastolic function, including time constant of relaxation Tau (15 ± 5 millisecond vs 12 ± 3 millisecond) and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (8 ± 3 mm Hg vs 6 ± 2 mm Hg), in LV-SF-GFP and WT mice, respectively, at 10 months (data in parentheses) and 15 months of age (data not shown). These findings confirm previous observations that up to this age, Gaa−/− mice do not exhibit overt left ventricle dysfunction.35

Effect of LV-SF-GAA HSC transplantation on cardiac structure and parameters. (A-B) Response of cardiac hypertrophy to LV-SF-GAA transplantation. The right and left ventricular mass of 10-month-old (n = 6 in all groups) and 15-month-old (n = 5 for LV-SF-GFP and n = 7 for LV-SF-GAA) mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP is significantly higher than for WT mice. The left ventricular mass of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA is significantly lower than for the age-matched mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP. The same holds for the right ventricular mass at month 15 (*P < .05, **P < .01, or ***P < .01 indicate a significant difference between groups). (C) Representative ultrasound images display the short axis of the left ventricle (left, 2-dimensional guided; right, M-mode) of WT and Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA (W indicates ventricular wall; L, left ventricular lumen). The Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP display a larger left ventricular wall thickness than the WT mice and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA, both at end diastole and at end systole (not shown). Furthermore, it shows that mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP have a lower heart rate than both the WT mice and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA by the increased duration of the cardiac cycle. (D) The left ventricular wall thickness at end diastole (LVEDT) in LV-SF-GFP–treated mice (n = 6) is increased compared with WT mice at 8 and 10 months of age (n = 6). Reduction of LVEDT is accomplished in mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA compared with LV-SF-GFP–treated mice at 8 (n = 6), 10 (n = 6), and 15 months of age (n = 3) (**P < .01). (E) Relative heart rate normalized after LV-SF-GAA treatment. At 10 months of age LV-SF-GFP–treated mice (n = 10) had a lower than normal (WT mice; n = 11) heart rate. Treatment with LV-SF-GAA (n = 11) normalized the heart rate (**P < .01). BPM indicates beats per minute.

Effect of LV-SF-GAA HSC transplantation on cardiac structure and parameters. (A-B) Response of cardiac hypertrophy to LV-SF-GAA transplantation. The right and left ventricular mass of 10-month-old (n = 6 in all groups) and 15-month-old (n = 5 for LV-SF-GFP and n = 7 for LV-SF-GAA) mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP is significantly higher than for WT mice. The left ventricular mass of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA is significantly lower than for the age-matched mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP. The same holds for the right ventricular mass at month 15 (*P < .05, **P < .01, or ***P < .01 indicate a significant difference between groups). (C) Representative ultrasound images display the short axis of the left ventricle (left, 2-dimensional guided; right, M-mode) of WT and Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA (W indicates ventricular wall; L, left ventricular lumen). The Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP display a larger left ventricular wall thickness than the WT mice and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA, both at end diastole and at end systole (not shown). Furthermore, it shows that mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP have a lower heart rate than both the WT mice and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA by the increased duration of the cardiac cycle. (D) The left ventricular wall thickness at end diastole (LVEDT) in LV-SF-GFP–treated mice (n = 6) is increased compared with WT mice at 8 and 10 months of age (n = 6). Reduction of LVEDT is accomplished in mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA compared with LV-SF-GFP–treated mice at 8 (n = 6), 10 (n = 6), and 15 months of age (n = 3) (**P < .01). (E) Relative heart rate normalized after LV-SF-GAA treatment. At 10 months of age LV-SF-GFP–treated mice (n = 10) had a lower than normal (WT mice; n = 11) heart rate. Treatment with LV-SF-GAA (n = 11) normalized the heart rate (**P < .01). BPM indicates beats per minute.

After transplantation of the GAA-overexpressing cells, both relative right ventricular and left ventricular mass decreased in LV-SF-GAA–treated animals compared with LV-SF-GFP mice (Figure 3A-B), accompanied by a restoration of left ventricular wall thickness toward levels observed in WT mice (Figure 3D). Heart rate also returned toward the levels observed in WT mice (Figure 3E), whereas mean aortic pressure (108 ± 3 mm Hg), fractional shortening (41% ± 1%), left ventricular dP/dtP30 (8110 ± 840 mm Hg/s), Tau (14 ± 4 milliseconds), and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (8 ± 2 mm Hg) remained principally unaffected (not shown).

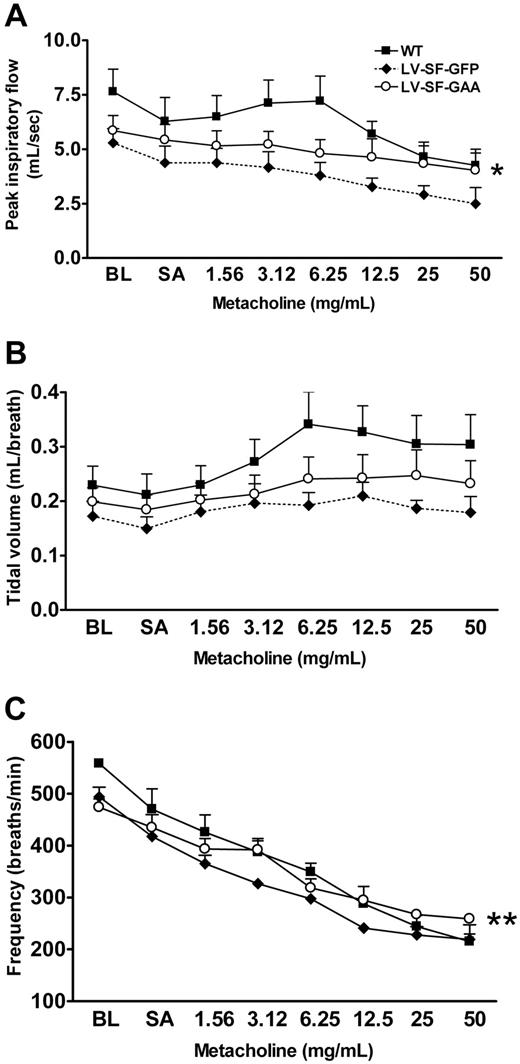

Transplantation of GAA-expressing HSCs improves respiratory function

Gaa−/− mice are known to have reduced respiratory function.5 Whole-body plethysmography was performed on WT, LV-SF-GFP– and LV-SF-GAA–treated mice to test respiratory function (Figure 4). The parameters tested were PIF, TV, and breathing frequency. PIF, TV, and breathing frequency were both significantly reduced in the LV-SF-GFP mice relative to the WT mice. The LV-SF-GAA–treated mice scored significantly better than the LV-SF-GFP mice in PIF and frequency of breathing (Figure 4).

Improved respiratory function in LV-SF-GAA–treated mice. Whole-body plethysmography was performed to determine (A) peak inspiratory flow, (B) tidal volume, and (C) frequency of breathing in 11-month-old mice (WT, n = 5; LV-SF-GFP, n = 3; LV-SF-GAA, n = 6, at 9 months after transplantation). All mice were exposed to increasing doses of nebulized metacholine to test muscular weakness or exhaustion of Gaa−/− mice. The peak inspiratory flow, tidal volume, and frequency of breathing are reduced in animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP compared with WT mice. LV-SF-GAA transplantation improves both parameters relative to LV-SF-GFP (*P < .05, **P < .01). BL indicates baseline; SA, saline.

Improved respiratory function in LV-SF-GAA–treated mice. Whole-body plethysmography was performed to determine (A) peak inspiratory flow, (B) tidal volume, and (C) frequency of breathing in 11-month-old mice (WT, n = 5; LV-SF-GFP, n = 3; LV-SF-GAA, n = 6, at 9 months after transplantation). All mice were exposed to increasing doses of nebulized metacholine to test muscular weakness or exhaustion of Gaa−/− mice. The peak inspiratory flow, tidal volume, and frequency of breathing are reduced in animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP compared with WT mice. LV-SF-GAA transplantation improves both parameters relative to LV-SF-GFP (*P < .05, **P < .01). BL indicates baseline; SA, saline.

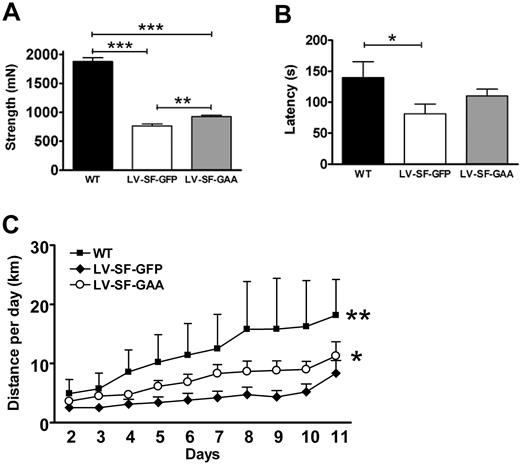

Transplantation of GAA-expressing HSCs improves motor performance

Although the deposition of glycogen was less reduced in skeletal muscle than in other tissues, we tested the effect of treatment on muscle strength and motor performance of LV-SF-GAA–treated mice. As expected, the muscle strength of all paws of WT mice was significantly (P < .001) higher than that of LV-SF-GFP– (2.5-fold) and LV-SF-GAA–treated (2-fold) mice (Figure 5A). However, LV-SF-GAA–treated mice were also significantly stronger (1.2-fold; P = .002) than LV-SF-GFP–treated mice, showing efficacy on skeletal muscle strength. From the age of 6 months onward motor performance was tested by determining latencies on an accelerating rotarod and activity in running wheels. WT mice stayed significantly longer on the rod than LV-SF-GFP mice (P < .05). The difference between LV-SF-GAA–treated and LV-SF-GFP–treated mice (Figure 5B) was not significant. Notably, 3 LV-SF-GFP–treated mice of 10 stayed less than 1 minute on the rod, which was not observed in the LV-SF-GAA–treated and WT mice. In the running wheels, WT mice performed best, and LV-SF-GAA–treated mice ran significantly longer (P < .02) distances than LV-SF-GFP–treated controls (Figure 5C).

Motor performance. (A) The sum strength in forelimbs and hind limbs was measured more than 150 days after transplantation (range, 158-316 days; WT: n = 6; average age, 208 days; range, 167-252 days; LV-SF-GFP: n = 13; average age, 210 days; range, 158-316 days; LV-SF-GAA: n = 22; average age, 212 days; range, 158-316 days). Congenic age-matched WT animals are stronger than both Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP or with LV-SF-GAA, and the mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA are significantly stronger than the LV-SF-GFP mice (**P < .01; ***P < .001). (B) Rotarod performance. The latency (seconds on the rotarod) was determined in all treatment groups at the age of 10 months (WT, n = 6; LV-SF-GFP, n = 10; LV-SF-GAA, n = 14). WT mice perform significantly better (P < .05) than animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP. Mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA perform on average better than animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP (not significant) but worse than WT animals (not significant). (C) Running wheel performance. Running distances increased during the 11 days that they were measured (WT, n = 3; LV-SF-GFP, n = 5; LV-SF-GAA, n = 6). WT mice run longer distances than both mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP (**P < .01) and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA, and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA mice perform better than animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP (*P < .02).

Motor performance. (A) The sum strength in forelimbs and hind limbs was measured more than 150 days after transplantation (range, 158-316 days; WT: n = 6; average age, 208 days; range, 167-252 days; LV-SF-GFP: n = 13; average age, 210 days; range, 158-316 days; LV-SF-GAA: n = 22; average age, 212 days; range, 158-316 days). Congenic age-matched WT animals are stronger than both Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP or with LV-SF-GAA, and the mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA are significantly stronger than the LV-SF-GFP mice (**P < .01; ***P < .001). (B) Rotarod performance. The latency (seconds on the rotarod) was determined in all treatment groups at the age of 10 months (WT, n = 6; LV-SF-GFP, n = 10; LV-SF-GAA, n = 14). WT mice perform significantly better (P < .05) than animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP. Mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA perform on average better than animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP (not significant) but worse than WT animals (not significant). (C) Running wheel performance. Running distances increased during the 11 days that they were measured (WT, n = 3; LV-SF-GFP, n = 5; LV-SF-GAA, n = 6). WT mice run longer distances than both mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP (**P < .01) and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA, and mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA mice perform better than animals that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP (*P < .02).

High GAA expression in transplanted HSCs has no adverse effect on hematopoietic system function

High expression levels of GAA should not affect hematopoietic cell differentiation and function. White and red blood cell counts and parameters, as well as platelets (supplemental Table 4), did not show differences due to GAA overexpression. Phenotyping BM, spleen, and PB cells showed that numbers of T lymphocytes (CD3, CD4, CD8), monocytes/granulocytes (CD11b, Gr1), and cells with stem cell markers (Sca-1, c-Kit) did not differ significantly among WT, LV-SF-GFP–, and LV-SF-GAA–treated mice except for PB cells with B-lymphocyte markers (B220, IgM, CD19). B220+/IgM+ cells of LV-SF-GAA–treated mice were increased (supplemental Figure 2; 3.8-fold; P < .01) relative to the level of 188 ± 118 cells/μL in WT mice with a similar trend in LV-SF-GFP–treated mice (2.4-fold; P = .1). This effect was not observed in BM or spleen and did not result in increased overall numbers of B lymphocytes, assuming a blood volume of 2 mL and 8.5% of total mouse BM cells per femur.36 Functional colony cultures of BM and spleen hematopoietic progenitor cells did not yield differences between WT and the other groups of mice as determined by enumeration of early (erythroid burst-forming unit) and late (erythroid colony-forming unit [CFU-E]) erythroid, granulocyte/macrophage-CFU, and megakaryocyte-CFU progenitors (supplemental Table 5). By experimental design, the progeny of both the LV-SF-GFP– and LV-SF-GAA–transduced HSCs represents a minority of blood cells produced and, therefore, also of progenitor cells. For this reason, this analysis does not fully exclude possible functional changes by overexpression of GAA. However, the sustained and highly stable production of GAA under competitive repopulation conditions does not point to any impairment of transduced long-term repopulating cells.

Discussion

Transplantation of genetically engineered HSCs after a clinically relevant subablative conditioning regimen leads to ectopic overexpression of GAA in PB cells with major clearances of glycogen in heart, diaphragm, stomach, uterus, lung, liver, and spleen. As a consequence, cardiac remodeling was reversed, respiratory function was improved, and skeletal muscle strength and motor performance were significantly ameliorated proportional to the reduction of glycogen storage. The presence of cells that overexpress GAA did not affect overall hematopoietic cell number and function. In line with the intrinsic tolerogenic nature of HSC transplantation and stability of enzyme levels up to the current observation time of 1.5 years, antibodies often observed patients with Pompe disease treated with ERT could not be detected after highly immunogenic challenging with human GAA.

Coexistence of a normal hematopoietic and immune system sustained from nontransduced stem cells and a minority of GAA-producing cells is an inherent strength of the experimental strategy and will facilitate potential clinical implementation. In the current experiments, leading to a high level of efficacy in adult mice, the contribution of transgene-expressing cells is on average roughly 35% of hematopoietic cells, which indicates that a low-dose cytoreductive conditioning regimen, such as the busulphan regimen applied in the successful clinical trial for adenosine deaminase–deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID),37 might well be sufficient in human patients. The minimum myelosuppressive conditioning regimen and stem cell numbers required for optimal efficacy need to be further established in a follow-up study along the lines described previously for α- and β-thalassemia,38,39 as is the minimum transgene copy number per cell.

At the time of treatment, the mice have glycogen deposition in heart, smooth muscle, and skeletal muscle, but overt pathologic manifestation occurs when mice age. Because patients severely affected with Pompe disease die within the first year of life from cardiac and respiratory failure, early prevention or reversal of disease progression is essential for clinical efficacy. Because early intervention and high ERT dosing are essential requirements to treat early-onset Pompe disease successfully, transplantation of HSCs with high expression levels of the enzyme should have increased benefit if applied immediately after diagnosis.

Significant reductions of glycogen content and improved motor function have been obtained through systemic AAV vector administration.40,41 The response of skeletal muscles to genetically modified HSC transplantation is limited relative to that of heart and other organs. This problem is organ specific and also observed in enzyme replacement therapy. To further improve clearance of skeletal muscle fibers after gene-corrected HSC transplantation, enhanced secretion of chimeric GAA may benefit,42 as well as early intervention, ie, at the time of weaning or in neonates when glycogen deposition is still limited. Similar to ERT2 and contrasting storage disorders characterized by severe neuronal impairment, genetically modified HSC transplantation does not influence glycogen deposition in brain tissue, which, however, does not elicit known clinical features in mice and humans and may therefore not be essential, but the option of clearance in brain tissue warrants further investigation.

Recently, it was reported that HSC expression of human GAA in combination with ERT could lead to partial correction and immune tolerance.18 Our results show that 30- to 50-fold levels in the hematopoietic system are well tolerated. These expression levels reduced glycogen content and improved cardiac remodeling significantly. In contrast, the low levels of GAA expression achieved in the study by Douillard-Guilloux et al18 required adjunctive ERT to reduce heart glycogen content. Conversely, in the latter report glycogen storage in the gastrocnemius muscle was significantly reduced without ERT, as opposed to a more limited, statistically insignificant reduction in glycogen content in the QF muscle examined in our study. However, the high GAA expression does significantly improve motor performance and, thus, resulted in long-term functional phenotype reduction.

During the near lifespan follow-up of the mice, neither numerical nor functional aberrancies in hematopoiesis were discerned. The risk of insertional mutagenesis is presently under active investigation. It is of note that the SIN-LV vectors used have a low genotoxicity profile relative to γ-retroviral vectors,43 but clinical trials with the latter have also shown that insertional mutagenesis may have diverse outcomes, eg, development of clonal T-cell proliferation in the X-linked SCID trials44,45 and clonal dominance augmented by insertional activation in X-linked chronic granulomatous disease,46 which may be partly related to the underlying disease. We do not per se advocate the use of the SF promoter for clinical application; however, aberrant clonal proliferation has not been observed in successful clinical γ-retroviral gene therapy trials for treatment of the enzyme deficiency adenosine deaminase–deficient SCID,37,47 both cases using viral promoters and one notably a similar promoter as in our Pompe study. More large-scale experiments are required to establish the safety profile of therapeutic LV vectors at disease-specific backgrounds. We prefer to replace the strong SF promoter by cellular promoters, such as the phosphoglycerate kinase or elongation factor 1α promoter, which are less likely to hit and activate cellular protooncogenes, as has been shown for Evi1 by sensitive cell-based assays48 and are currently developing sequence-optimized human GAA constructs to further improve protein expression per transgene copy. If this strategy works for the human GAA gene, the weaker cellular promoters should replace the SF promoter to achieve both therapeutic clinical efficacy and improved safety.

Allogeneic HSC transplantation has been explored for more than 2 decades as a treatment method for lysosomal storage diseases. Beneficial effects are achieved in Hurler disease (mucopolysaccharidosis I),11 Krabbe disease (globoid cell leukodystrophy),12 and MLD.49 However, disease-related pathology progression by HSC transplantation is mostly partial and transplant-related morbidity and mortality remain significant hurdles. Overexpression of a corrective transgene in autologous HSCs would represent a major benefit, because it combines the advantages of a single intervention with the patient's own cells and that of ERT, as has been shown for MLD.16 In Pompe disease, allogeneic HSCs would probably be ineffective because of the normally low levels of GAA activity in blood cells.

The present study convincingly shows that an efficient overnight transduction of HSCs results in genetically engineered progeny that overproduces GAA, which cross corrects affected cell types with prominent and sustained therapeutic efficacy, especially in the life-threatening cardiac and respiratory functional impairments as well as in complete clearance of glycogen in liver and spleen. Lifelong therapy by an endogenous transgene product is an obvious advantage over lifelong ERT and a prerequisite to clinical application. The results may contribute to further development of an efficacious ex vivo HSC-mediated gene therapeutic method that concomitantly induces immune tolerance to the transgene product.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Luigi Naldini for the third-generation LV vector plasmids; Drs Axel Schambach and Christopher Baum for the mutated WPRE element; Dr Geeske van Woerden and Vera van Dis of the Neurosciences Department, Erasmus MC, for assisting in the use of the Rotarod and grip measurement devices; and Laura van den Dool for assistance with biochemical analysis.

This work was supported by the European Commission's 5th, 6th, and 7th Framework Programs (contracts QLK3-CT-2001-00 427-INHERINET, LSHB-CT-2004-005242-CONSERT and grant agreement no. 222878-PERSIST), by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research ZonMW (program grant 434-00-010), and The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO (project 021.002.129).

Authorship

Contribution: N.P.v.T. contributed to design of experimental work, executed technical work, designed figures, and wrote the manuscript; M.S. executed most of the technical work and contributed to experimental design and writing of the manuscript; F.S.F.A.K. executed technical work; M.C.d.W. executed technical work and contributed to the manuscript; E.F. contributed to experimental design and executed technical work; T.P.V., E.H.J., M.A.W., and P.v.d.W. executed technical work; M.A.K. assisted in technical work; B.J.S. and A.T.v.d.P. contributed to editing the manuscript; B.N.L. contributed to experimental design and editing the manuscript; D.J.D., A.J.J.R., and M.M.V. contributed to experimental design and writing the manuscript; and G.W. designed the project, contributed to the experimental design, and writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gerard Wagemaker, Department of Hematology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Dr Molewaterplein 50, 3015 GE Rotterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: g.wagemaker@erasmusmc.nl.

References

Author notes

N.P.v.T. and M.S. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. In vivo LV expression of human GAA. (A) Gaa−/− mice received a transplant with 5 × 105 Lin− cells transduced with the therapeutic vector (LV-SF-GAA) at a multiplicity of infection of 9 to 10. The GAA activity in peripheral leukocytes of a total of 32 LV-SF-GAA–treated mice was measured, starting from day 29 after transplantation to the last data point at day 549 (n = 4). Fifteen Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP served as negative controls. The leukocyte α-glucosidase levels (3.4 ± 1.3 nmol/h/mg) of congenic FVB mice (n = 6) are indicated by the dotted line. (B) Illustration of GAA expression and lysosomal localization in BM cells of a WT, a Gaa−/− mouse, and a Gaa−/− mouse that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA–transduced HSCs harvested 8 months after transplantation [blue nuclear DAPI (4′-6′-diamidine-2-phenylindole) stain and green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 immunostaining for GAA protein; original magnification ×1000]. (C) At 8 months after transplantation, Western blot analysis of GAA expression in BM and spleen (SPL) shows a known pattern of 95-kDa (intermediate species) and 76-kDa (mature species) forms of human GAA, reflecting GAA synthesis, posttranslational modification, maturation, and lysosomal localization.22 Mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP do not express human GAA, whereas the level of GAA expression in WT animals is too low to detect. A dilution of recombinant human GAA (rhGAA) of 110 kDa serves as a marker. (D) Plasma GAA enzyme levels. Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA showed variable but detectable GAA enzyme levels in plasma compared with background activity (BL) detected in Gaa−/− mice. Low activity levels were also detected in WT mice. Numbers in the figure that accompany the plasma data represent GAA activity (nmol/h/mg) in leukocytes. (E) Reconstitution of GAA activity in Gaa−/− mice. GAA activity in tissues of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA and age-matched WT mice at 10 months of age (n = 3-6 mice for all tissues, except for LV-SF-GFP brain). *Significant difference (P < .05) of mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA compared with both WT and LV-SF-GFP mice. †Significant difference (P < .05) between mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA and LV-SF-GFP but not between LV-SF-GAA and WT mice. (F) Tolerance to rhGAA in Gaa−/− mice that received a transplant of LV-SF-GAA. Both WT (n = 2) and LV-SF-GFP–treated Gaa−/− (n = 2) mice responded by the generation of anti–human GAA antibodies after a first injection of rhGAA (Myozyme, 20 mg/kg) with Freund adjuvant (rhGAA + A) followed by a second injection of rhGAA without adjuvant 2 weeks later. LV-SF-GAA–treated Gaa−/− mice (n = 13) did not respond to the challenge with rhGAA. (G) The percentage of reconstituted male cells in BM of LV-SF-GFP and LV-SF-GAA female recipients (chimerism) was determined by Y chromosome Sry q-PCR and corrected for overall genomic DNA by Gapdh q-PCR (n = 6). (H) Copy number of LV vector integrations. Q-PCR was used to determine the average copy number in male BM cells (n = 6). Horizontal lines in panels G and H represent mean value.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/26/10.1182_blood-2009-11-252874/4/m_zh89991054200001.jpeg?Expires=1769492525&Signature=XoX6BE6nVCRSjdcMkjAj-2l4hKP7lbOuJX9WQjS2w9FmgePT5s5bqis9YJoX3rGM8EnUYBVaejUXq~53jDtxJVEWZLn29KkfJtVcTIJDWgINtibSA5xbPKZsXj0A~eaECTxkzjVvC1ZNgxlpO1r81bcFfKGi1Qsp6eIWJJc2fENo3hNHxF3MA9iCVq24pxZOQ0k2tfs6v0oGzRMTIykVL4KkQcf1CFEw52GFF5ExOvYSppowbHjK5xxE6hUXwa2IZ48OU3UO~nWbKUGh6bthIoO0M27yvdMEqdrXtJaIIMrDUeyT6cK635C4FMzAjQhjpGsJ1BqF-djqE3Hdl-BJEg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)