Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) has a broad spectrum of clinical behaviors; some cases are self-limited, whereas others involve multiple organs and cause significant mortality. Although Langerhans cells in LCH are clonal, their benign morphology and their lack (to date) of reported recurrent genomic abnormalities have suggested that LCH may not be a neoplasm. Here, using 2 orthogonal technologies for detecting cancer-associated mutations in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material, we identified the oncogenic BRAF V600E mutation in 35 of 61 archived specimens (57%). TP53 and MET mutations were also observed in one sample each. BRAF V600E tended to appear in younger patients but was not associated with disease site or stage. Langerhans cells stained for phospho-mitogen–activated protein kinase kinase (phospho-MEK) and phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (phospho-ERK) regardless of mutation status. High prevalence, recurrent BRAF mutations in LCH indicate that it is a neoplastic disease that may respond to RAF pathway inhibitors.

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare proliferative disorder of epidermal antigen-presenting cells.1,2 It can follow a mild clinical course and even resolve spontaneously,3,4 but it can also involve multiple organ systems with fatal consequences in 20% of disseminated cases. LCH's etiology is unknown. The benign morphology of its proliferating cells and its characteristic inflammatory infiltrates suggest that LCH may be an inflammatory disorder,3 and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-17A, has been reported.5 However, the pathologic Langerhans cells (LCs) in LCH are clonal.6,7 Although clonality is an important feature of neoplasia, recurrent genomic abnormalities would be required to demonstrate that LCH is a neoplasm; and, to date, none has been reported.8 Therefore, we interrogated LCH tissue samples using a mass spectrometric method that tests for the presence of a large number of cancer-associated mutations in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material.

Methods

Patients and samples

Paraffin blocks archived in the Departments of Pathology at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Children's Hospital Boston were retrieved and diagnoses confirmed. For bone lesions, paraffin blocks containing undecalcified curettings or adjacent soft tissue were used for DNA extraction. Fresh frozen material was retrieved from an LCH case stored at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the analysis of anonymized, discarded tissue.

Mass spectrometric genotyping

Blocks were cored in regions of highest histiocyte density, and DNA was extracted using QIAmp DNA FFPE tissue kit (QIAGEN catalog #56404). Multiplexed mass spectrometric genotyping using the OncoMap platform was performed as described in supplemental data (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).9,10 After an initial screen using iPLEX chemistry, which includes 1047 assays interrogating 983 unique mutations across 115 genes (supplemental Tables 6-7), candidate mutations were validated using homogeneous mass extension (hME) chemistry on unamplified genomic DNA.9

Pyrosequencing

DNA was amplified using the PyroMark Q24 BRAF kit (QIAGEN). Polymerase chain reaction products were sequenced with 5-CACTCCATCGAGATTTC-3 as a sequencing primer and CTGCATGCATGCA as the dispensation order using the PyroMark MD System (Biotage AB and Biosystems). Samples with mutant allele frequencies less than 4% were considered wild-type; those with frequencies of 4% or greater were considered mutant.

Immunofluorescence

Anti-CD1a (clone MTB1, Ventana Medical Systems) was applied to sections from paraffin blocks followed by Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated goat anti–mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) F(ab′)2 fragments (Cell Signaling Technologies). Then, antiphospho-mitogen–activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) or antiphospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) antibodies (rabbit IgG from Cell Signaling Technologies) were applied followed by Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG F(ab′)2 fragments (Cell Signaling Technologies). Nuclei were counterstained using 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories). Controls using class- or subclass-matched nonspecific immunoglobulins showed no specific staining.

Statistical analysis

Fisher exact test was performed for categorical comparisons, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed for 2-sample comparison of continuous measures. A Pearson correlation coefficient (r) test was used to determine the relationship between 2 continuous measures. All tests were 2-sided and considered significant at the .05 level. Unadjusted and adjusted exact logistic regression models were also constructed to test for an association between the BRAF V600E mutation and clinical characteristics.

Results and discussion

To test for cancer-related mutations in LCH, we retrieved 35 paraffin blocks from the pathology archives of our hospitals (Cohort I). DNA extracted from LCH-enriched cores was analyzed for the presence of cancer-related mutations using OncoMap, a mass spectrometric method of allele detection optimized for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material.9,10 BRAF V600E was identified in 17 of 34 evaluable samples (one case yielded insufficient DNA for analysis; Table 1). Other validated mutations included MET E168D and TP53 R175H in one case each. A second set of 27 samples was independently retrieved and analyzed (Cohort II). Two had insufficient DNA for analysis, but BRAF V600E was found in 16 of the remaining 25.

To confirm the presence of BRAF V600E using an orthogonal technology, 44 samples were pyrosequenced (insufficient material remained to sequence all samples; Table 1). Results were consistent with OncoMap, except for 2 cases: one in which pyrosequencing detected wild-type alleles in a sample with insufficient DNA for OncoMap and one in which pyrosequencing detected BRAF V600E in a sample called wild-type by OncoMap. Because our pyrosequencing assay is a clinically validated test executed in a laboratory certified pursuant to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment, we assigned mutant status to this sample. Finally, pyrosequencing detected BRAF V600E in a freshly frozen LCH sample, suggesting that the mutation is not an artifact of fixation technique (Table 1). Overall, BRAF V600E was present in 35 of 61 evaluable cases for a mutation frequency of 57%. As controls, we examined 5 cases of dermatopathic lymphadenopathy, a reactive proliferative disease that includes an LC component, and 4 cases of Rosai-Dorfman disease, a histiocytic disorder of macrophage lineage. No BRAF mutations were detected in these samples (supplemental Table 1).

The median age of patients who carried the mutation was less than that of patients who did not (P = .03, supplemental Table 2); age was also associated with mutation status in the unadjusted exact logistic model (P = .04) but not in the adjusted exact logistic model (P = .09) (supplemental Table 3). No other available clinical characteristics correlated with the presence of BRAF V600E, including disease site or stage. Our incomplete clinical dataset precludes drawing any inferences about the effect of mutation status on clinical outcomes.

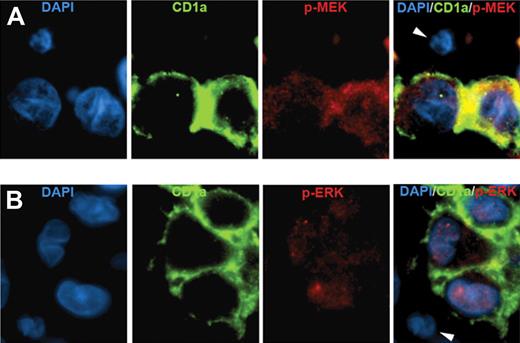

Three indirect criteria indicated that the mutant BRAF alleles were specifically in LCs. First, the proportion of BRAF mutant alleles determined by pyrosequencing was 3-fold to 21-fold higher in LC-enriched material obtained by laser-capture microdissection compared with LC-depleted material (supplemental Table 4). Second, the abundance of mutant BRAF alleles in each sample correlated with the percentage of LCs in those samples (r = 0.68, P < .001, supplemental Figure 1). The proportion of mutant alleles was approximately half the proportion of LCs in the samples, suggesting that the mutation was present in a single heterozygous copy, although this is speculative. Third, LCs specifically stained for phospho-MEK and phospho-ERK (Figure 1), indicating activation of the BRAF signaling cascade in those cells. The intensity of phospho-MEK and phospho-ERK staining by immunohistochemistry (supplemental Figure 2) did not vary with BRAF mutational status (supplemental Table 5), suggesting that BRAF pathway activation may occur generally in LCH but that BRAF mutation is not its only cause. BRAF gene duplication has been associated with pathway activation in pediatric low-grade astrocytomas,11,12 but we detected no gene duplication by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in 43 analyzable samples.

Immunofluorescence analysis of BRAF pathway activation in LCH. (A) LCH sample stained with DAPI (blue), anti-CD1a (green), antiphospho-MEK (red), and a merged image of all 3 stains. (B) LCH sample stained with DAPI (blue), anti-CD1a (green), antiphospho-ERK (red), and a merged image of all 3 stains. Arrowheads indicate CD1a-negative cells that are also negative for phospho-MEK and phospho-ERK. (Technical details described in supplemental Methods.)

Immunofluorescence analysis of BRAF pathway activation in LCH. (A) LCH sample stained with DAPI (blue), anti-CD1a (green), antiphospho-MEK (red), and a merged image of all 3 stains. (B) LCH sample stained with DAPI (blue), anti-CD1a (green), antiphospho-ERK (red), and a merged image of all 3 stains. Arrowheads indicate CD1a-negative cells that are also negative for phospho-MEK and phospho-ERK. (Technical details described in supplemental Methods.)

The presence of BRAF V600E in 57% of archived LCH specimens from 2 independent institutions strongly suggests that LCH is a neoplasm. This finding adds LCH to a growing list of neoplastic diseases in which the transformed cell harbors this mutation.13,14 BRAF V600E is also present in benign nevi, and this has been cited as an example of oncogene-induced senescence in vivo.15 A similar mechanism may underlie examples of spontaneous remission in LCH as well as the frequent appearance of overexpressed wild-type p53.8,16 The presence of BRAF V600E in pulmonary LCH was surprising considering the fact that 70% of these lesions have been reported to be nonclonal.17 We speculate that, in susceptible persons, cigarette smoke may generate the transversion that characterizes this allele. This would result in multiple transformed clones throughout the lung that, in the aggregate, produce polyclonal disease with the same mutation in all of the clones. A similar situation has been described in nevi.18

As with nevi, of course, additional genetic changes may be required in order for LCs harboring BRAF V600E to progress to LCH. Although OncoMap tests a large number of alleles, it is not exhaustive, and additional abnormalities not measured by this test may yet be discovered in LCH. Nonetheless, specific inhibition of BRAF signaling is effective in blocking the proliferation of melanoma cells that have additional genomic abnormalities.19,20 A similar approach may also produce responses in patients with LCH.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matt Davis and Charlie Hatton for OncoMap technical support, the Center for Advanced Molecular Diagnostics at Brigham & Women's Hospital for pyrosequencing, Natalie Vena for FISH analysis technical support, Dr Stephen Sallan for encouraging the LCH research program, and Dr Phillip Kantoff for his help.

This work was supported in part by the Histiocytosis Association of America, Team Ippolittle/Deloitte of the Boston Marathon Jimmy Fund Walk, the Mufson family, and a US Public Health Service grant (AI050225). The Pathology Specimen Locator Core is supported by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA06516) to the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: G.B.-V. obtained tissue cores, performed laser-capture microdissection, isolated DNA, performed immunofluorescence, and analyzed immunohistochemistry; J.-A.V. conducted pathology evaluation and analyzed immunohistochemistry; B.A.D. evaluated clinical characteristics for each case; B.B. initiated tissue and DNA acquisition for OncoMap; M.L.C. performed immunohistochemistry; F.C.K. performed pyrosequencing; A.H.L. performed FISH; K.E.S. performed statistical analyses; S.M.K. performed OncoMap analysis; L.E.M. performed and interpreted OncoMap analysis; L.A.G. performed and oversaw OncoMap analysis; W.C.H. and M.M. evaluated and oversaw OncoMap analysis; M.D.F. reviewed all pathology diagnoses and immunohistochemistry and identified appropriate control cases; and B.J.R. conceived and coordinated the genotyping project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Barrett J. Rollins, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: barrett_rollins@dfci.harvard.edu.