Abstract

A central role for the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in innate immunity has been recently defined by its ability to limit proinflammatory mediators. Although glucocorticoids (GCs) exert potent anti-inflammatory effects in innate immune cells, it is currently unknown whether the mTOR pathway interferes with GC signaling. Here we show that inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin or Torin1 prevented the anti-inflammatory potency of GC both in human monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells. GCs could not suppress nuclear factor-κB and JNK activation, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, and the promotion of Th1 responses when mTOR was inhibited. Interestingly, long-term activation of monocytes with lipopolysaccharide enhanced the expression of TSC2, the principle negative regulator of mTOR, whereas dexamethasone blocked TSC2 expression and reestablished mTOR activation. Renal transplant patients receiving rapamycin but not those receiving calcineurin inhibitors displayed a state of innate immune cell hyper-responsiveness despite the concurrent use of GC. Finally, mTOR inhibition was able to override the healing phenotype of dexamethasone in a murine lipopolysaccharide shock model. Collectively, these data identify a novel link between the glucocorticoid receptor and mTOR in innate immune cells, which is of considerable clinical importance in a variety of disorders, including allogeneic transplantation, autoimmune diseases, and cancer.

Introduction

Current immunosuppressive regimens to avoid allogeneic rejection after organ or bone marrow transplantation largely rely on drugs with potent immunosuppressive effects predominantly affecting different steps during T-cell activation. There is, however, increasing evidence that also the innate immune system is critical for the fate of allografts and may as well exert detrimental effector functions.1-9 For example, monocytes are the first cells to enter the allograft immediately after transplantation; and recently, monocyte influx, rather than T-cell influx, into the allograft has been proposed to correlate with graft rejection.9 Monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) initiate the inflammatory response after stimulation by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands and trigger the subsequent adaptive T-cell response.10,11 However, the molecular pathways targeted by immunosuppressants in particular when they are used as combination therapy and the ensuing functional consequences are still incompletely defined.

Among the currently used immunosuppressants calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), such as cyclosporine A (CsA) or FK506, and antimetabolites, such as mycophenolic acid (mycophenolate mofetil [MMF]) are thought to exert distinct but rather modest effects on innate immune cells.12,13 On the contrary, glucocorticoids (GCs) have a high anti-inflammatory potential and, consequently, are crucial constituents of various immunosuppressive regimens applied in many inflammatory conditions.14 GCs differentially affect cytokine production in monocytes/macrophages with a prominent shift toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype.15 Furthermore, DC differentiation and maturation are profoundly suppressed by GCs, leading to DCs with a tolerizing capacity characterized by increased interleukin-10 (IL-10), but blocked IL-12 secretion.16,17 At the molecular level, GCs profoundly inhibit nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling via the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) to prevent recruitment of active NF-κB dimers to the κB promoter.18 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway that specifically leads to the activation of the transcription factor subunit c-Jun is blocked by transrepression through nuclear GR binding.19 Thus, NF-κB and JNK are major targets of GC to exert their anti-inflammatory action. Interestingly, NF-κB and JNK are important for the allogeneic immune response as their hyperactivation may ultimately lead to allograft rejection in diverse experimental models.20-24

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, which is known to control metabolism, growth, and cell survival, has recently emerged as key regulator of innate immune cell homeostasis.25,26 Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin in human monocytes or myeloid DCs promotes IL-12, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-6 production via the transcription factor NF-κB but blocks the release of IL-10 via Stat3.27-30 Conversely, deletion of TSC2, the key negative regulator of mTOR, diminishes NF-κB but enhances Stat3 activity and reverses the proinflammatory cytokine shift.27 Rapamycin can augment inflammation and pulmonary injury by enhancing NF-κB activity in the lung of tobacco-exposed mice.31 Interestingly, various inflammatory disorders have been observed in rapamycin-treated patients, such as interstitial pneumonitis, anemia of the chronic inflammatory type, and severe forms of glomerulonephritis, despite the concomitant use of GCs.32-34 Clinical observations suggest that rapamycin-induced pulmonary pneumonitis cannot be ameliorated by high-dose glucocorticoid therapy.35,36 Moreover, kidney transplant patients on rapamycin display enhanced expression of NF-κB-related proinflammatory expression pathways and monocyte enrichment compared with CsA patients after being on steroid therapy.37

In the present study, we determined the role of mTOR in monocytes and myeloid DCs in the context of other currently used immunosuppressive drugs. Our data demonstrate a conspicuous repressive role of mTOR in innate immune cells that interferes with the potent anti-inflammatory effects of GCs.

Methods

Cell isolation and culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from buffy coats by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare). Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes were isolated from PBMCs by positive selection using CD14 (Miltenyi) microbeads and a magnetic cell separator. Myeloid DCs were isolated as described.26 THP-1, a promonocytic cell line derived from human acute lymphocytic leukemia patient, was obtained from the DSMZ. Tsc2+/+ p53−/− and Tsc2−/− p53−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts were a kind gift of David Kwiatkowski. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) containing penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), glutamine (2mM), and 10% fetal calf serum that had been inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 4.5 g/L glucose, 2mM l-glutamine, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 10% fetal calf serum.

Reagents

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Dexamethasone, MMF, CsA, and FK506 were purchased from Calbiochem. Rapamycin was used from Calbiochem or was provided by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals with identical results. Torin1 was a kind gift of Nathanael Gray.

Cell stimulation and collection of supernatants

PBMCs (1 × 106 cells/mL), monocytes (1 × 106 cells/mL), or THP-1 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mL) were incubated in 24-well culture plates (Falcon; BD Biosciences) with CsA (250, 125, or 62.5 ng/mL), MMF (2.5, 0.5, or 0.1 ng/mL), or dexamethasone (250, 25, or 2.5nM) for 1 hour in 37°C at 5% CO2 and 95% humidity before 100nM rapamycin was added. Cells were left untreated or stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Cell-free supernatants were harvested, stored at −20°C, and thawed at the time of analysis for IL-12p40, IL-10, and TNF-α production via Luminex.

Whole-blood stimulation

Heparinized blood from immunosuppressed renal transplant patients was diluted 1:5 in medium; 1 mL was added into 24-well plates and directly stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 20 hours. Cytokines were determined in cell-free supernatants by Luminex. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the General Hospital Vienna according to the declaration of Helsinki (EK 407/2007). Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Luminex

Cytokines were measured by Luminex Technology to IL-12p40, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 (all R&D Systems) and IL-23 (Bender MedSystems).

RNAi

THP-1 cells were transfected in full medium without antibiotics with 100nM ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool human TSC2 or 100nM ON-TARGETplus siCONTROL nontargeting pool (Dharmacon RNAi Technologies) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) following the protocol provided by the manufacturers. Cells were used after 72 hours.

Analysis of signal transduction events

Monocytes or THP-1 were stimulated as indicated. Extract preparation and Western blotting were done as described.27 Antibodies were p70S6K, p-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), p-S6 (Ser 240/244), S6, p-c-Jun, c-Jun, GAPDH (all Cell Signaling Technology), and TSC2, β-tubulin, p-Erk (Tyr204), Erk, and p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Cell fractionation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were obtained by discontinuous density gradient centrifugation. Briefly, cells were applied onto a preformed iodixanol gradient and centrifuged in the cold at 1000g for 15 minutes. Subsequently, the different layers containing either cytosolic proteins or intact nuclei were harvested and solubilized in Laemmli buffer containing 150mM dithiothreitol by incubation at 95°C for 5 minutes.

T-cell proliferation

T lymphocytes were cultured at 1 × 106 cells/mL in 96-well flat-bottom microplates (Corning Life Sciences). T cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL OKT-3, cultured for 2 and 3 days in the presence or absence of 25nM dexamethasone and/or 100nM rapamycin as indicated, and pulsed with [3H]TdR (1 μCi/well) for the last 20 hours of the culture. Assays were performed in triplicate.

T-cell differentiation

Monocytes were incubated with medium, 100nM rapamycin, and/or 25nM dexamethasone for 90 minutes and then stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 24 hours. Then the cells were washed and incubated with allogeneic PBMCs at a ratio of 1:1 for one week. Afterward, IFN-γ was determined in the supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. In parallel, the cells were primed with 50 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate and 200 ng/mL ionomycin for 5 hours in the presence of 10 μg/mL brefeldin A for the final 3 hours of culture. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fix & Perm (An der Grub) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti–IFN-γ, PE-labeled anti–IL-4, and allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD4 (all BD Bioscience); then cells were washed and analyzed on a FACSCanto II.

Quantitative RT-PCR

A total of 2 × 106 monocytes in a 6-well plate pretreated with or without dexamethasone and rapamycin as indicated were stimulated for 8 hours with 100 ng/mL LPS, and total RNA was extracted in TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNA was generated by Superscript II (Invitrogen) as suggested by the manufacturer. mRNA levels were determined by TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for IL-12p40, IL-10, and 18S rRNA (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI Prism 7000 in a multiplex PCR. mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA.

Reporter gene assays

The reporter construct for NF-κB was from Stratagene. p65 transactivation domain (TAD) and Gal4-Luc plasmids were a kind gift of Neil Perkins. In all experiments, a Renilla luciferase construct was cotransfected to normalize expression. The reporter plasmids were transfected in THP-1 cells with Lipofectamine LTX and Plus Reagent for 24 hours according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were transfected with Lipofectamine for 3 to 5 hours. Afterward, the cells were treated with rapamycin and LPS as indicated for additional 20 hours. Lysates were prepared using passive lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega).

LPS shock model

Rapamycin was dissolved at 16.8 mg/mL in dimethyl sulfoxide and the stock solution was further diluted to 150 μg/mL with phosphate-buffered saline for injection. Dexamethasone was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 12.5 mg/mL. LPS from E coli 0111:B4 was from Sigma-Aldrich (#L2630). Male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks) were injected intraperitoneally with 1.5 mg/kg per day rapamycin or vehicle for 2 consecutive days. On the day of the LPS challenge, some groups were additionally treated with 300 μg/kg dexamethasone subcutaneously or vehicle; and after 30 minutes, mice were challenged intraperitoneally with 20 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg LPS as indicated.38 Survival was monitored twice daily for 156 hours. All animal experiments were discussed and approved by the institutional ethics committee and the Austrian laws (GZ 68.205/0204-C/GT/2007 and GZ 68.205/0053-II/10b/2008).

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Student t test was used to detect statistical significance. Patient cytokine levels were compared with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett post test.

Results

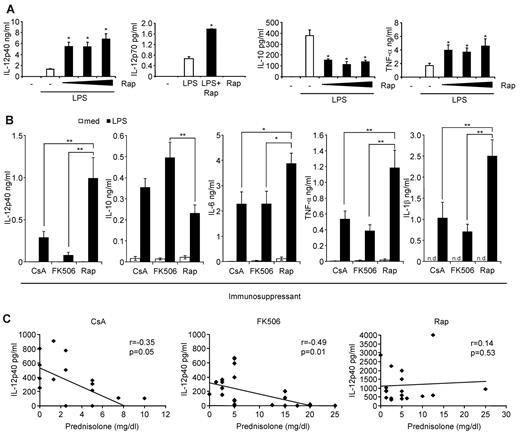

Hyperactivation of the inflammatory immune response in rapamycin-treated kidney transplant recipients

Our previous results indicated that rapamycin hyperactivates the inflammatory immune response in vitro in humans and in vivo in mice.26,27 We confirmed in human monocytes that rapamycin strongly enhanced the production of IL-12p40, IL-12p70, and TNF-α, whereas production of IL-10 was blocked (Figure 1A). To substantiate these results ex vivo, we analyzed the production of inflammatory cytokines in whole blood from stable renal transplant recipients treated with rapamycin, CsA, or FK506 along with MMF and prednisolone. Apart from the steroid dose of FK506 patients, the patient characteristics were similar between the groups (Table 1). Remarkably, patients on rapamycin were exceptionally susceptible to mount a profound proinflammatory response after ex vivo LPS stimulation reflected by a significantly higher production of the inflammatory markers IL-12p40, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β (Figure 1B). Moreover, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was significantly suppressed in these patients compared with FK506-treated patients (Figure 1B). Ex vivo addition of rapamycin to whole blood from CsA- or FK506-treated patients similarly augmented IL-12p40 and suppressed IL-10 expression (data not shown). Interestingly, IL-12p40 production significantly correlated with the dose of prednisone only in CsA- and FK506-treated patients but not in rapamycin-treated patients (Figure 1C). These results establish that rapamycin-treated kidney transplant patients display a profound proinflammatory profile on LPS activation compared with CNI-treated patients.

The mTOR pathway regulates inflammatory cytokine production in human monocytes in vitro and in transplant patients ex vivo. (A) Human monocytes obtained from healthy subjects were preincubated with rapamycin (Rap; 1, 10, or 100nM) as indicated and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. IL-12p40, IL-10, and TNF-α in cell-free supernatants were determined after LPS stimulation for 20 hours. For measurement of IL-12p70 production, monocytes were additionally stimulated with 30 ng/mL IFN-γ. Data are mean ± SEM for 3 donors. (B) Whole blood from kidney transplant patients receiving CsA, FK506, or Rap was left untreated or stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 20 hours. IL-12p40, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in cell-free supernatants were determined by Luminex assays. Data are mean ± SEM of 21 (CsA), 28 (FK506), or 19 (Rap) donors. *P < .05. **P < .01. n.d. indicates not determined. (C) Correlation analysis of IL-12p40 production versus prednisone dose in the patients from panel B.

The mTOR pathway regulates inflammatory cytokine production in human monocytes in vitro and in transplant patients ex vivo. (A) Human monocytes obtained from healthy subjects were preincubated with rapamycin (Rap; 1, 10, or 100nM) as indicated and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. IL-12p40, IL-10, and TNF-α in cell-free supernatants were determined after LPS stimulation for 20 hours. For measurement of IL-12p70 production, monocytes were additionally stimulated with 30 ng/mL IFN-γ. Data are mean ± SEM for 3 donors. (B) Whole blood from kidney transplant patients receiving CsA, FK506, or Rap was left untreated or stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 20 hours. IL-12p40, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in cell-free supernatants were determined by Luminex assays. Data are mean ± SEM of 21 (CsA), 28 (FK506), or 19 (Rap) donors. *P < .05. **P < .01. n.d. indicates not determined. (C) Correlation analysis of IL-12p40 production versus prednisone dose in the patients from panel B.

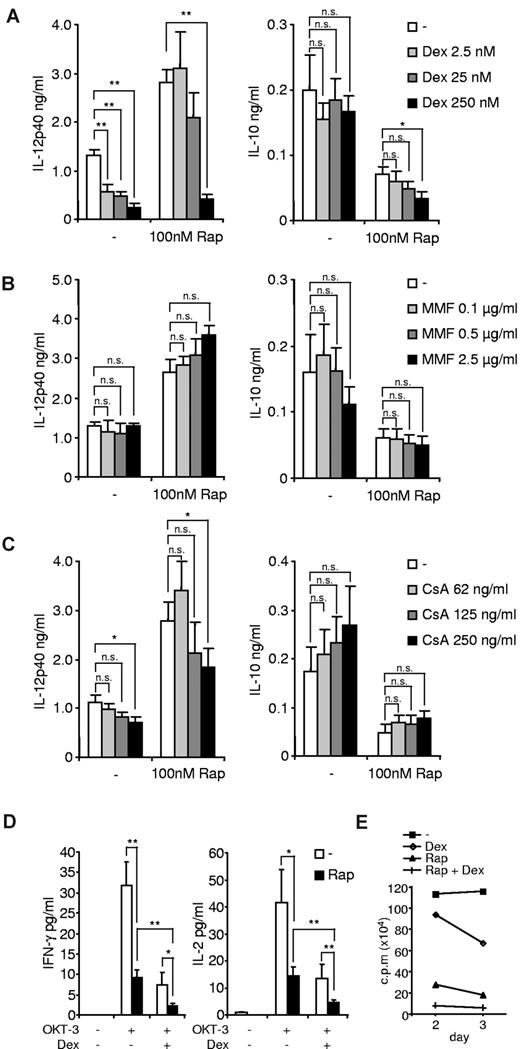

Interference of rapamycin and other immunosuppressants in PBMCs

As therapeutic principle, mTOR inhibition is clinically applied with other immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory drugs to enable an efficient immunosuppression. As we observed a powerful capability of rapamycin-treated patients to mount a proinflammatory response in the presence of MMF or GC, we investigated whether these immunosuppressants are able to interfere with the immunomodulatory capacity of rapamycin at the cellular level. Freshly isolated human PBMCs were treated with different clinically relevant (2.5 and 25nM) concentrations and a supramaximal dose (250nM) of dexamethasone.39 Dexamethasone effectively suppressed IL-12p40 production in LPS-stimulated PBMCs while leaving the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 largely unaffected (Figure 2A). Strikingly, dexamethasone, at clinically relevant doses, was not able to block the rapamycin-induced enhanced production of IL-12p40, whereas only a supramaximal dose of dexamethasone inhibited the proinflammatory effects of rapamycin (Figure 2A). We obtained similar data, when mTOR was inhibited with 10nM rapamycin (data not shown). These results suggested that the mTOR pathway is connected with GR signaling.

Dexamethasone (Dex), but not MMF or CsA, interferes with mTOR inhibition. PBMCs treated with the indicated concentrations of (A) Dex, (B) MMF, or (C) CsA for 30 minutes were incubated with 100nM rapamycin (Rap) or medium and then stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. IL-12p40 and IL-10 in cell-free supernatants were assessed after 20 hours. Data are mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05. **P < .01. n.s. indicates not significant. (D) PBMCs were treated with 25nM Dex and/or 100nM Rap and then stimulated with 10 μg/mL OKT-3 as indicated. IFN-γ and IL-2 were determined in the supernatant after 24 hours. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. (E) T cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL OKT-3 and 100nM Rap and/or 25nM Dex as indicated. Proliferation was measured on days 2 and 3 and is expressed as the means of triplicates of 2 independent donors.

Dexamethasone (Dex), but not MMF or CsA, interferes with mTOR inhibition. PBMCs treated with the indicated concentrations of (A) Dex, (B) MMF, or (C) CsA for 30 minutes were incubated with 100nM rapamycin (Rap) or medium and then stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. IL-12p40 and IL-10 in cell-free supernatants were assessed after 20 hours. Data are mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05. **P < .01. n.s. indicates not significant. (D) PBMCs were treated with 25nM Dex and/or 100nM Rap and then stimulated with 10 μg/mL OKT-3 as indicated. IFN-γ and IL-2 were determined in the supernatant after 24 hours. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. (E) T cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL OKT-3 and 100nM Rap and/or 25nM Dex as indicated. Proliferation was measured on days 2 and 3 and is expressed as the means of triplicates of 2 independent donors.

As expected, MMF, which inhibits DNA synthesis, did not modify LPS-stimulated cytokine secretion of IL-12p40/IL-10 and did not significantly alter the proinflammatory effects of rapamycin in PBMCs (Figure 2B). Treatment with CsA resulted in a statistically nonsignificant trend to down-regulate IL-12p40 and increase IL-10 production of LPS-activated PBMCs (Figure 2C). Moreover, CsA was not able to affect the proinflammatory phenotype of rapamycin-treated PBMCs (Figure 2C).

However, testing the immunosuppressive potency of GC and rapamycin after T-cell receptor activation, we observed that treatment with dexamethasone and rapamycin synergistically suppressed IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion after OKT-3 stimulation (Figure 2D), and both drugs also synergistically inhibited T-cell proliferation (Figure 2E). These results demonstrate that rapamycin specifically prevents the anti-inflammatory effects of GC in PBMCs, but both drugs act in a synergistic immunosuppressive manner.

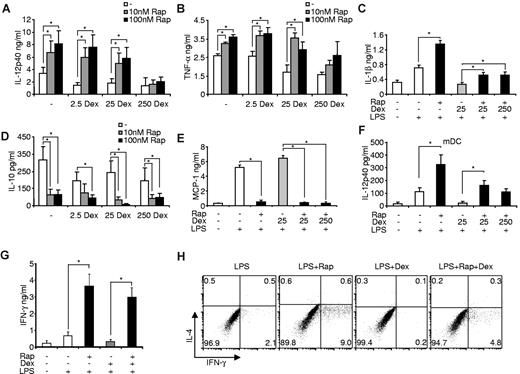

mTOR inhibition prevents the anti-inflammatory effect of dexamethasone in human monocytes

To specifically allocate the observed reciprocal influence of rapamycin and dexamethasone on inflammatory cytokines to a distinct cell type in PBMCs, we assessed purified human monocytes, the cardinal inflammatory cells in human blood. Dexamethasone and rapamycin did not significantly affect apoptosis rates in LPS-treated monocytes (data not shown). Remarkably, rapamycin augmented IL-12p40, TNF-α, and IL-1β production in LPS-stimulated monocytes despite the presence of clinically relevant doses of the glucocorticoid (Figure 3A-C). Again, only high doses of dexamethasone prevented the proinflammatory activity of rapamycin (Figure 3A-B), indicating that rapamycin and dexamethasone might modulate similar downstream signaling pathways, whereas MMF and CNI did not significantly modulate cytokine production (data not shown). Moreover, rapamycin potently inhibited IL-10, and also the anti-inflammatory chemokine MCP-1, which could not be rescued by addition of dexamethasone (Figure 3D-E). As DCs are the major antigen-presenting cells that link innate with adaptive immunity, we wanted to assess whether inhibition of mTOR is able to overcome the anti-inflammatory effects of GCs also in this cell compartment. Using freshly isolated myeloid DCs, we found a similar conspicuous regulation of IL-12p40 production by rapamycin and dexamethasone (Figure 3F). These results suggest that the antagonism of mTOR and GR at the cellular level occurs both in monocytes and peripheral myeloid DCs.

Rapamycin (Rap) prevents the anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone (Dex) in monocytes. Freshly isolated monocytes were pretreated with the indicated amounts of Dex, incubated in the presence or absence of Rap and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. After 20 hours, cell-free supernatants were harvested and measured for (A) IL-12p40, (B) TNF-α, (C) IL-1β, (D) IL-10, and (E) MCP-1 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05. (F) Myeloid DCs (mDC) were treated with 100nM Rap, Dex, and LPS as indicated. IL-12p40 in the supernatants was determined after 20 hours. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < .05. (G) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of IFN-γ in culture supernatants of allogeneic PBMCs primed for 7 days with the indicated monocytes. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < .05. (H) Intracellular cytokine staining of IL-4 and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells from allogeneic PBMCs primed with the indicated monocytes for 7 days and then activated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin for 5 hours. Data are representative of 4 experiments performed.

Rapamycin (Rap) prevents the anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone (Dex) in monocytes. Freshly isolated monocytes were pretreated with the indicated amounts of Dex, incubated in the presence or absence of Rap and stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. After 20 hours, cell-free supernatants were harvested and measured for (A) IL-12p40, (B) TNF-α, (C) IL-1β, (D) IL-10, and (E) MCP-1 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05. (F) Myeloid DCs (mDC) were treated with 100nM Rap, Dex, and LPS as indicated. IL-12p40 in the supernatants was determined after 20 hours. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < .05. (G) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of IFN-γ in culture supernatants of allogeneic PBMCs primed for 7 days with the indicated monocytes. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < .05. (H) Intracellular cytokine staining of IL-4 and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells from allogeneic PBMCs primed with the indicated monocytes for 7 days and then activated with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin for 5 hours. Data are representative of 4 experiments performed.

Rapamycin reestablishes a potent Th1-polarizing capacity of dexamethasone-treated monocytes

Inhibition of mTOR in monocytes promotes the differentiation of T helper 1 (Th1) cells,27 whereas glucocorticoids are known to interfere with the Th1-polarizing potency of TLR-activated cells.40 Therefore, we compared the ability of LPS-stimulated monocytes treated with rapamycin and dexamethasone to prime CD4+ Th1 responses. Whereas rapamycin-treated cells strongly enhanced the production of IFN-γ and the differentiation of CD4+ Th1 cells, dexamethasone-treated monocytes suppressed Th1 priming (Figure 3G-H). Strikingly, rapamycin reverted the suppressive effects of dexamethasone-treated cells and reestablished strong IFN-γ production and Th1 polarization (Figure 3G-H). We conclude that mTOR inhibition in monocytes potently promotes Th1 polarization of CD4+ T cells despite the presence of dexamethasone.

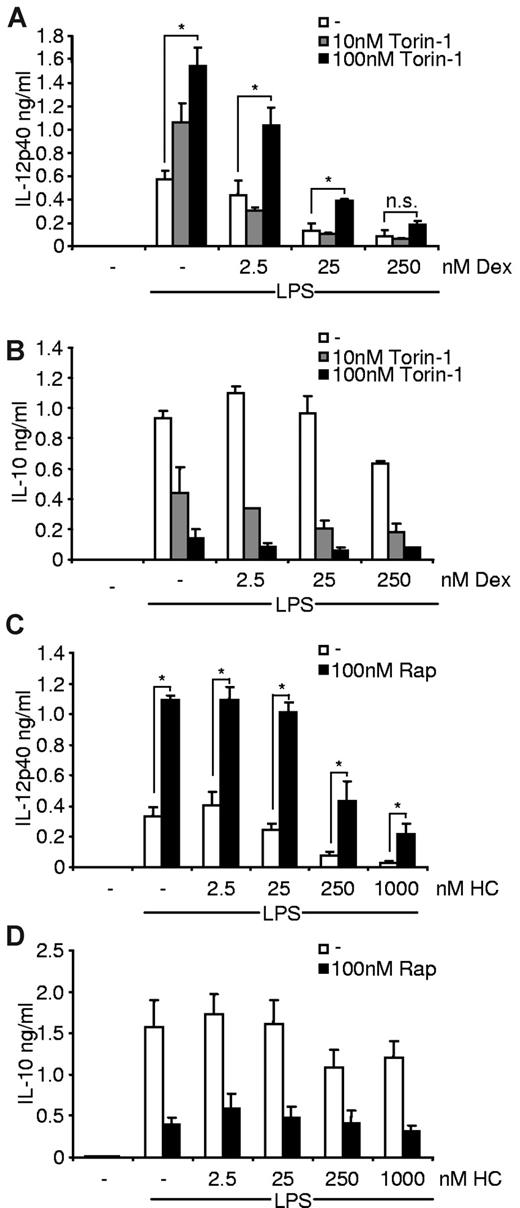

mTOR and the GR differentially regulate the activation of NF-κB in monocytes

To further address the molecular targets responsible for the observed reciprocal regulation of the proinflammatory response, we used pharmacologically distinct agents to modulate the mTOR pathway and the GR. Indeed, the mTOR inhibitor Torin-1 was able to enhance IL-12p40 production despite the presence of dexamethasone (Figure 4A) and, moreover, blocked IL-10 production in human monocytes (Figure 4B). On the other hand, treatment of monocytes with hydrocortisone similar to dexamethasone did not prevent rapamycin-induced hyperproduction of IL-12p40 (Figure 4C), whereas IL-10 was not modulated by hydrocortisone (Figure 4D). Together, these results indicate that the proteins mTOR and the GR directly mediate the reciprocal effects of the inhibitors on inflammatory cytokine production.

Torin-1 and hydrocortisone reciprocally mimic the immunomodulatory effects of rapamycin (Rap) and dexamethasone (Dex). Human monocytes were pretreated with the indicated amounts of (A-B) Dex or (C-D) hydrocortisone (HC) and then incubated with (A-B) Torin-1 or (C-D) Rap and finally stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. (A,C) IL-12p40 and (B,D) IL-10 were determined in the supernatants after 20 hours (mean ± SEM; n = 3). *P < .05. n.s. indicates not significant.

Torin-1 and hydrocortisone reciprocally mimic the immunomodulatory effects of rapamycin (Rap) and dexamethasone (Dex). Human monocytes were pretreated with the indicated amounts of (A-B) Dex or (C-D) hydrocortisone (HC) and then incubated with (A-B) Torin-1 or (C-D) Rap and finally stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS. (A,C) IL-12p40 and (B,D) IL-10 were determined in the supernatants after 20 hours (mean ± SEM; n = 3). *P < .05. n.s. indicates not significant.

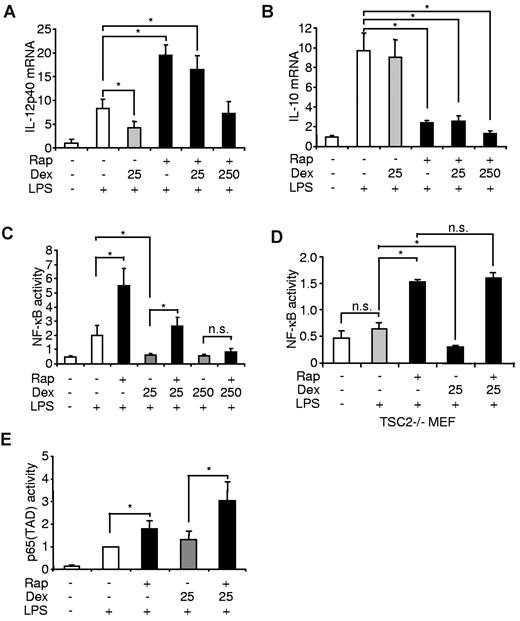

To gain insight if the interference of mTOR and the GR on inflammatory cytokine production is mediated via transcriptional processes, we isolated mRNA from LPS-treated monocytes that were treated with rapamycin and/or dexamethasone. Although dexamethasone inhibited IL-12p40 mRNA in LPS-stimulated cells, clinical relevant doses of dexamethasone did not interfere with the proinflammatory effect of mTOR inhibition in these cells (Figure 5A). Dexamethasone did not affect IL-10 mRNA production and could not reverse the potent suppression of IL-10 mRNA induced by rapamycin (Figure 5B). Inhibition of mTOR augments the activation of NF-κB,27 whereas dexamethasone has potent inhibitory effects on NF-κB activity.41,42 Therefore, we examined whether mTOR and the GR might reciprocally interact with NF-κB. Although dexamethasone completely suppressed NF-κB activation in LPS-stimulated monocytic THP-1 cells, dexamethasone could no longer repress this transcription factor in the presence of rapamycin (Figure 5C). Only at a supramaximal dose, dexamethasone blocked NF-κB activation when mTOR was inhibited (Figure 5C). Next, we analyzed rapamycin- and dexamethasone-dependent NF-κB activation in Tsc2−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts, which display augmented mTOR signaling and are therefore refractory to LPS-induced NF-κB activation27 (Figure 5D). Although dexamethasone decreased NF-κB in LPS-stimulated cells, dexamethasone did not block rapamycin-induced NF-κB hyperactivation, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory action of the GR involves the activation of mTOR signaling (Figure 5D). The transactivation domain (TAD) of p65 recruits specific cofactors to enhance the transcriptional process.43 Interestingly, p65(TAD) was hyperactivated when mTOR was inhibited in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells, whereas dexamethasone could not decrease this activity either alone or in the presence of rapamycin, suggesting that the TAD of p65 is not reciprocally regulated by mTOR and the GR (Figure 5E). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the potent inhibitory effects of dexamethasone on the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB are abrogated by rapamycin in monocytes, indicating that a major part of the reciprocal regulation of proinflammatory cytokines by mTOR and the GR are mediated at the level of NF-κB signaling.

mTOR and the GR differentially regulate the activation of NF-κB in monocytes. Human monocytes were treated as indicated. After 8 hours of stimulation, (A) IL-12p40 and (B) IL-10 mRNA were assessed by reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction. mRNA levels are depicted as increase over the unstimulated controls and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 donors. (C) THP-1 and (D) Tsc2−/− cells were transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid and treated as indicated. Luciferase activity is shown as the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (E) THP-1 cells were transfected with a Gal4 luciferase reporter and an expression plasmid encoding a p65(TAD)-Gal4 fusion. Luciferase activity is shown as the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P < .05. n.s. indicates not significant.

mTOR and the GR differentially regulate the activation of NF-κB in monocytes. Human monocytes were treated as indicated. After 8 hours of stimulation, (A) IL-12p40 and (B) IL-10 mRNA were assessed by reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction. mRNA levels are depicted as increase over the unstimulated controls and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 donors. (C) THP-1 and (D) Tsc2−/− cells were transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid and treated as indicated. Luciferase activity is shown as the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (E) THP-1 cells were transfected with a Gal4 luciferase reporter and an expression plasmid encoding a p65(TAD)-Gal4 fusion. Luciferase activity is shown as the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P < .05. n.s. indicates not significant.

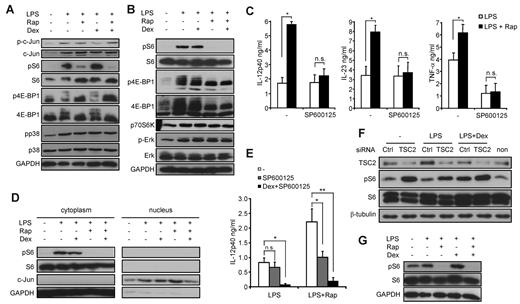

Rapamycin mediates proinflammatory effects via the GR-sensitive JNK signaling pathway

To further dissect the molecular mechanisms apart from NF-κB that might be modulated by mTOR and the GR, we investigated whether dexamethasone is able to directly interfere with mTOR signaling. Dexamethasone did not considerably affect the phosphorylation status of S6 or 4E-BP1, 2 downstream mediators of mTOR, in monocytes or THP-1 cells after 30 minutes of LPS stimulation (Figure 6A-B). In contrast, dexamethasone blocked the phosphorylation of c-Jun (Figure 6B), an essential transcription factor subunit important for IL-12p40 production, whereas the mitogen-activated protein kinases Erk-1/2 and p38 were not modulated either by rapamycin or dexamethasone (Figure 6A-B). Recent data demonstrated a selective enhancement of JNK activity in mTOR-inhibited monocytes independent of c-Jun phosphorylation.27 Consistent with these results, SP600125, a specific inhibitor of JNK, completely abolished the enhanced production of IL-12p40, IL-23, and TNF-α by rapamycin (Figure 6C). To identify the underlying molecular mechanism explaining how increased JNK activity on mTOR blockade may lead to enhanced transcriptional activity, we directly assessed the nuclear levels of c-Jun. Rapamycin increased the nuclear levels of c-Jun, whereas dexamethasone prevented the effects of mTOR inhibition (Figure 6D). Hence, one molecular mechanism contributing to the proinflammatory action of rapamycin is the selective enhancement of JNK activity leading to increased nuclear c-Jun levels on TLR engagement. However, the additional usage of dexamethasone to rapamycin- and SP600125-treated cells further down-regulated IL-12p40 production after 24 hours to a level comparable with dexamethasone-treated cells only (Figure 6E), indicating that dexamethasone may exert additional effects to affect IL-12p40 expression. Therefore, we analyzed whether long-term treatment with dexamethasone might modulate the mTOR pathway. Strikingly, we observed that LPS stimulation of THP-1 cells for 24 hours up-regulated TSC2 protein levels (Figure 6F). Dexamethasone completely blocked the LPS-induced increase of TSC2 levels and led to a concurrent activation of the mTOR pathway as shown by phosphorylation of S6 (Figure 6F). Activation of S6 negatively depended on TSC2 as knockdown of TSC2 increased S6 phosphorylation under all conditions tested (Figure 6F). These results were also observed in LPS-stimulated monocytes, where long-term treatment with dexamethasone increased S6 activity as well, whereas rapamycin abrogated the positive input signal from the GR to the mTOR pathway (Figure 6G). These results reveal a novel link between the GR and the mTOR pathway at the level of TSC2 and suggest that long-term treatment with dexamethasone may activate the mTOR signaling to regulate the inflammatory response.

Rapamycin (Rap) mediates proinflammatory effects via activation of JNK and inhibition of TSC2. (A) Human monocytes or (B) THP-1 cells were incubated with 25nM dexamethasone (Dex), 100nM Rap, and 100 ng/mL LPS for 30 minutes as indicated. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot. (C) Monocytes were treated with 20μM SP600125, 100nM Rap, or LPS as indicated. IL-12p40 in the supernatants was determined after 20 hours. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < .05. (D) Equal amounts of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of THP-1 cells stimulated as indicated for 30 minutes were analyzed by immunoblotting. (E) Monocytes were treated as indicated, and IL-12p40 was analyzed in the supernatants after 20 hours. *P < .05. **P < .01. n.s. indicates not significant. (F) THP-1 cells were transfected with TSC2 or control (Ctrl) siRNA for 72 hours and then stimulated with LPS and/or 25nM Dex as indicated for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot. (G) Monocytes were stimulated as indicated for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot.

Rapamycin (Rap) mediates proinflammatory effects via activation of JNK and inhibition of TSC2. (A) Human monocytes or (B) THP-1 cells were incubated with 25nM dexamethasone (Dex), 100nM Rap, and 100 ng/mL LPS for 30 minutes as indicated. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot. (C) Monocytes were treated with 20μM SP600125, 100nM Rap, or LPS as indicated. IL-12p40 in the supernatants was determined after 20 hours. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < .05. (D) Equal amounts of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of THP-1 cells stimulated as indicated for 30 minutes were analyzed by immunoblotting. (E) Monocytes were treated as indicated, and IL-12p40 was analyzed in the supernatants after 20 hours. *P < .05. **P < .01. n.s. indicates not significant. (F) THP-1 cells were transfected with TSC2 or control (Ctrl) siRNA for 72 hours and then stimulated with LPS and/or 25nM Dex as indicated for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot. (G) Monocytes were stimulated as indicated for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot.

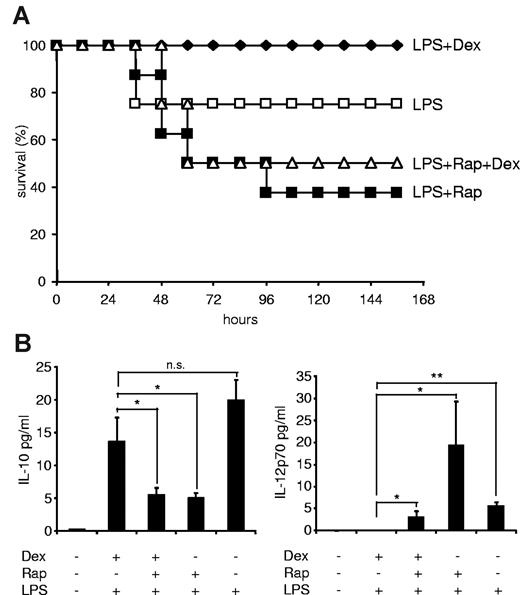

Rapamycin overrides the beneficial effects of dexamethasone in a murine sepsis model

After having established that mTOR and the GR reciprocally regulate inflammatory cytokine production in innate immune cells in vitro and ex vivo, we wondered whether the anti-inflammatory potency of GCs can be overcome by rapamycin in a murine LPS shock model. Recently, it has been shown that rapamycin augments lethality and proinflammatory cytokine production in LPS-treated C57BL/6 mice.30 Similarly, we also observed that rapamycin significantly increased mortality, when mice were injected with an LD30 LPS dose (Figure 7A), whereas dexamethasone completely prevented LPS-induced mortality (Figure 7A). Remarkably, dexamethasone was not able to rescue rapamycin-treated animals from death (Figure 7A), suggesting that rapamycin overrides the beneficial effects of GC also in a relevant inflammatory disease model in vivo. Whereas rapamycin inhibited IL-10 production in septic mice in vivo, dexamethasone did not reestablish IL-10 expression in mTOR-inhibited animals (Figure 7B). In addition, whereas dexamethasone completely repressed IL-12p70 production, rapamycin still allowed expression of bioactive IL-12p70 when the GR was activated in septic mice (Figure 7B). These results show that rapamycin enhances lethality in an LPS-shock model in vivo despite concurrent treatment with an effective anti-inflammatory intervention.

Dexamethasone (Dex) does not rescue the detrimental effect of rapamycin in a murine sepsis model. (A) Male C57BL/6 mice (n = 8/group) were injected with 1.5 mg/kg per day rapamycin (Rap; intraperitoneally; on 2 consecutive days), 300 μg/kg Dex (subcutaneously), or vehicle as described in “LPS shock model.” Then mice were challenged with 20 mg/kg LPS (intraperitoneally), and survival was monitored for 156 hours. (B) Mice were treated as in panel A but challenged with 10 mg/kg LPS. Serum samples were drawn at 6 hours and assayed for cytokines by Luminex. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4-6/group). *P < .05. **P < .01. n.s. indicates not significant.

Dexamethasone (Dex) does not rescue the detrimental effect of rapamycin in a murine sepsis model. (A) Male C57BL/6 mice (n = 8/group) were injected with 1.5 mg/kg per day rapamycin (Rap; intraperitoneally; on 2 consecutive days), 300 μg/kg Dex (subcutaneously), or vehicle as described in “LPS shock model.” Then mice were challenged with 20 mg/kg LPS (intraperitoneally), and survival was monitored for 156 hours. (B) Mice were treated as in panel A but challenged with 10 mg/kg LPS. Serum samples were drawn at 6 hours and assayed for cytokines by Luminex. Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4-6/group). *P < .05. **P < .01. n.s. indicates not significant.

Discussion

The molecular mode of action of medically approved drugs in transplantation medicine is still surprisingly ill defined, in particular when used in combination, but is mandatory for the assessment of drug-related risks and also novel therapeutic avenues. Hence, the elucidation of the effects of currently used immunosuppressive agents and regimens on the innate immune system is crucial as the evidence of the importance of monocytes and DCs for allograft rejection and survival is progressively increasing. Our studies reveal an unexpected and novel link between the GR and the mTOR pathway. Inhibition of mTOR enhances the production of IL-12, whereas it negatively regulates IL-10 in human monocytes and myeloid DCs after stimulation of TLRs in vitro as well as in BALB/c mice after infection with Listeria monocytogenes in vivo.25,27,29,44,45 In addition, rapamycin enhances the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD86, and it inhibits the T-cell inhibitory molecule PD-L1 on myeloid DCs of rapamycin-treated transplant patients.26

We now demonstrate that LPS-stimulated PBMCs of kidney-transplanted patients on a rapamycin-based immunosuppressive regimen displayed an elevated production of proinflammatory mediators, such as IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β ex vivo compared with patients on CNI. GCs are potent inhibitors of IL-12 production15,41 ; however, the steroid dose did not correlate with IL-12p40 production in PBMCs of rapamycin-treated patients, whereas the GC dose correlated with the expression of IL-12p40 in CsA- and FK506-treated patients. Therefore, we studied the impact of mTOR inhibition while simultaneously activating GR signaling for inflammatory cytokine signaling. The most potent GC dexamethasone interfered with the stimulatory effect of rapamycin on IL-12, TNF-α, or IL-1β production only at supramaximal concentrations but did not inhibit this proinflammatory potential at clinically relevant doses in human monocytes. On the other hand, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was suppressed by mTOR inhibition but was not significantly modulated by GC. Moreover, although dexamethasone-treated monocytes blocked the differentiation of Th1 cells, inhibition of mTOR in monocytes strongly promoted Th1 responses even in the presence of the glucocorticoid. This mutual regulation of proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory functions was dependent on mTOR and the GR as the mTOR inhibitor Torin1 or hydrocortisone, respectively, mimicked the effects of rapamycin and dexamethasone. Rapamycin and dexamethasone are known to have transcriptional-dependent and -independent effects on gene regulation; however, both drugs reciprocally modulated the mRNA levels of IL-12p40, indicating that mTOR and the GR modulate transcriptional events in human monocytes. Molecularly, IL-12p40 hyperactivation during mTOR inhibition is mediated by increased NF-κB activity, and dexamethasone could not inhibit this enhanced activity under physiologic doses. In addition, we found that rapamycin promoted JNK signaling by increasing nuclear c-Jun levels, whereas dexamethasone diminished c-Jun in the nucleus in the presence of mTOR inhibition.

A connection between the mTOR pathway and the GR has been established in many cell lines. In these cells, activation of the GR by GC induces the expression of RTP801 (also known as REDD1), which inhibits mTOR signaling.31,46-48 However, we have shown in innate immunocompetent cells that long-term treatment with GC activates mTOR signaling in LPS-stimulated monocytes by reducing the expression of TSC2. To our knowledge, these results are the first to show that the protein levels of TSC2 can be directly altered via GC and/or via the inflammatory stimulus LPS. Moreover, LPS-stimulated PBMCs of kidney transplant tuberous sclerosis patients, who have steady-state activation of the mTOR pathway because of mutations in TSC1 or TSC2, show an diminished ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines compared with control patients who could be restored after conversion to rapamycin despite the presence of GC.49 These data lend further support to the concept that the mTOR pathway is a central control unit of inflammatory responses.

Clinically, it has been observed that distinct inflammatory side effects of mTOR inhibitors, including pneumonitis and glomerulonephritis, cannot be ameliorated with GC. For instance, mTOR inhibitor-induced pneumonitis requires the discontinuation of the mTOR inhibitor despite the concurrent use of GC.35,36 Moreover, myeloid DCs have a proinflammatory phenotype in rapamycin-treated patients despite concurrent prednisone therapy.26 Our current results that clinically applicable doses of GC cannot ameliorate the inflammatory events observed with mTOR inhibitor therapy may provide one molecular rationale for this unusual phenomenon. Moreover, they support the notion that discontinuation of the mTOR inhibitor in such events might be favorable rather than escalating the steroid.

In conclusion, we could show in this study that the GR is connected with the mTOR pathway in human monocytes to modulate inflammatory responses. The potent anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone were rendered ineffective in the presence of rapamycin, resulting in sustained production of proinflammatory cytokines. These data not only reveal a novel basic regulatory principle in innate immune cells but also may allow to better understand the interaction of currently used immunosuppressants within the innate immune cell compartment and finally may allow optimizing immunosuppressive protocols.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Barbara Vodenik and Margarethe Merio for excellent technical assistance.

T.W. and M.D.S. were supported by the Else-Kröner Fresensius Stiftung. C.L. and M.M. were supported by the Austrian Science Foundation FWF (SFB F28) and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Science and Research (GEN-AU III Austromouse).

Authorship

Contribution: T.W. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments and wrote the manuscript; M.P., C.K., K.K., C.L., and M.R. performed experiments; M. Haidinger collected clinical samples; M. Hengstschläger, M.M., G.J.Z., and W.H.H. gave technical support; and M.D.S. wrote the manuscript and supervised the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marcus D. Säemann, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Nephrology & Dialysis, Medical University Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: marcus.saemann@meduniwien.ac.at.