Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are potent antigen-presenting cells derived from hematopoietic progenitor cells and circulating monocytes. To investigate the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) during DC differentiation, maturation, and function, we profiled miRNA expression in human monocytes, immature DCs (imDCs), and mature DCs (mDCs). Stage-specific, differential expression of 27 miRNAs was found during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. Among them, decreased miR-221 and increased miR-155 expression correlated with p27kip1 accumulation in DCs. Silencing of miR-221 or overexpressing of miR-155 in DCs resulted in p27kip1 protein increase and DC apoptosis. Moreover, mDCs from miR-155−/− mice were less apoptotic than those from wild-type mice. Silencing of miR-155 expression had little effect on DC maturation but reduced IL-12p70 production, whereas miR-155 overexpression in mDCs enhanced IL-12p70 production. Kip1 ubiquitination-promoting complex 1, suppressor of cytokine signaling 1, and CD115 (M-CSFR) were functional targets of miR-155. Furthermore, we provide evidence that miR-155 indirectly regulated p27kip1 protein level by targeting Kip1 ubiquitination-promoting complex 1. Thus, our study uncovered miRNA signatures during monocyte differentiation into DCs and the new regulatory role of miR-221 and miR-155 in DC apoptosis and IL-12p70 production.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells in the immune system with the unique capacity to uptake and efficiently present antigens to naive T lymphocytes.1 DCs can also interact with B cells2 and natural killer (NK) cells3 and thus bridge the innate and adaptive immunity. DCs develop directly from myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow (BM) and circulating blood monocytes, ensuring that self versus non–self-discrimination is maintained in the steady state and during immunologic challenges.4 Through a series of differentiation events, progenitor cells develop into immature (imDCs) and then into mature DCs (mDCs). The developmental process ends with apoptotic cell death.5 During this process, genes that encode critical proteins involved in DC differentiation, maturation, and function are programmatically expressed.6,7 Integrated genomic and proteomic analysis suggests that many of these proteins are regulated at a post-transcriptional level.8 However, the underlying molecular mechanism is unclear.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have recently emerged as a major class of gene expression regulators linked to most biologic functions, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis.9,10 miRNAs are single-stranded RNA molecules approximately 19 to 24 nucleotides in length and post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by forming imperfect base pairing with sequences in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of target mRNAs. This interaction prevents protein accumulation by repressing translation or by inducing mRNA degradation.11 In general, miRNAs do not completely shut down gene expression of their targets but rather fine-tune their expression. Although more than 1000 human miRNAs have been annotated in the miRBase database (Version 16), their functions in the immune system, especially in DC development and function, have just begun to be explored.

The most studied miRNA in DCs is miR-155. miR-155−/− mice are defective in B- and T-cell immunity, but the role of miR-155 in antigen presentation by DCs remains controversial.12,13 miR-155 is known to modulate the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived DCs.14 miR-155 also targets DC-specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3 grabbing nonintegrin and reduces its pathogen binding ability on maturation.15 miR-34a and miR-21 are mildly increased during human monocyte differentiation into imDCs, and they coordinately regulate DC differentiation by targeting JAG1 and WNT1.16 Although miRNA profiling in monocyte-derived DCs has been reported,16,17 a systematic analysis of the miRNA profile during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs has not been performed. Moreover, few studies about miRNA regulation in DC apoptosis and function have been reported.

Here, we systematically analyzed miRNA signatures during human monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. We found that p27kip1, a key cell cycle inhibitor, was differentially expressed during DC development and maturation. DC apoptosis was at least regulated by miR-221 and miR-155 through targeting the 3′-UTRs of p27kip1 and Kip1 ubiquitination-promoting complex 1 (KPC1), respectively. miR-155 was also found to regulate IL-12p70 production by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS-1). Collectively, these data indicate the regulatory role of miR-221 and miR-155 in human DC development, apoptosis, and interleukin-12 (IL-12) production.

Methods

DC differentiation and maturation

In vitro human monocyte differentiation into DCs was performed as described with modifications.18 Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated through Ficoll-Hypaque (Mediatech Cellgro) density gradient centrifugation from buffy coats purchased from Memorial Blood Centers or blood from healthy donors after informed consent following the Declaration of Helsinki according to the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board-approved study. Monocytes were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using anti-CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Purified monocytes (> 95% purity) were cultured at 37°C in 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells per well) in 3 mL of serum-free AIM V medium (Invitrogen) containing human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, 100 ng/mL, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) and human interleukin-4 (IL-4, 20 ng/mL, R&D Systems). A total of 1 mL of fresh medium with GM-CSF and IL-4 was added to the cell cultures at day 3. Old medium was replaced by 3 mL fresh medium with GM-CSF and IL-4 at day 5. DCs were matured with IL-1β (10 ng/mL, R&D Systems), IL-6 (10 ng/mL, PeproTech), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, 10 ng/mL, R&D Systems), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, 1 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) on day 6, and DCs were harvested on day 8 or the indicated time.

Murine DCs were generated from BM cell culture in the presence of GM-CSF as described with modifications.19 Mice were maintained at the University of Minnesota Animal Facility in accordance with institutional guidelines. BM was collected from femurs and tibias of 8- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 mice (wild-type [WT]) and bic/mir-155−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Erythrocytes were lysed, passed through a nylon mesh, and cells washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with penicillin (50 U/mL), streptomycin (50 μg/mL), L-glutamine (2mM), 2-mercaptoethanol (50μM), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone). At day 0, BM cells were seeded at 2 × 106 cells per 100-mm dish (Fisher Scientific) in 10 mL medium containing recombinant murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL, R&D Systems). Three days later, another 10 mL medium containing murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) was added into the dish. For the induction of DC maturation, lipopolysaccaride (LPS, 1 μg/mL, catalog no. L2654, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to cell cultures for 24 hours at day 6. In some experiments, imDCs were further purified from suspension cells at day 6 using anti-CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). LPS was then added for the indicated time.

miRNA array analysis

Total RNA was isolated from purified monocytes, imDCs at day 6, and mDCs at day 8 using Trizol (Invitrogen) and subjected to custom miRNA microarray analyses.20 Data were analyzed and normalized as described.21 The microarray data have been deposited in the GEO public database under accession number GSE21708.

Real-time PCR analysis

Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline twice and lysed with TRIZOL reagent to isolate total RNA, which was followed by DNase digestion. Single-strand cDNA was synthesized using the Ncode miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). miRNA-specific primers were designed following the kit instruction and synthesized at the University of Minnesota DNA Core Facility. U6 and 5S RNA was used as endogenous controls. Primer sequences are detailed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Comparative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using SYBR Green SuperMix (Invitrogen) was performed in a 96-well plate and run in a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 57°C for 1 minute. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate or triplicate. The level of miRNA expression was measured using threshold cycle (Ct) according to the ΔΔCt method.22 To normalize the relative abundance of miRNAs, 5S RNA was used as an endogenous control.

Flow cytometric analysis

Antibodies and Fc blocking reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences or eBioscience. Flow cytometric analysis was carried out on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software Version 7.2.2 (TreeStar).

Apoptosis assays

Cells were harvested at the indicated time points, washed, labeled with annexin V-allophycocyanin (APC; eBioscience) for 30 minutes on ice, and subsequently stained with propidium iodide (PI; 1 μg/mL, Invitrogen). Annexin V/PI staining was analyzed by flow cytometry. Sub-G0 analysis of cell apoptosis was also used. Briefly, cells were washed with 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid/phosphate-buffered saline and fixed with 90% ethanol for at least 30 minutes at −20°C. The cells were then washed, and cellular DNA was stained with RNase (50 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) and PI (10 μg/mL) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by flow cytometry.

DNA constructs

An miR-155 expression cassette containing the human miR-155 hairpin sequence and flanking regions was cloned from human genomic DNA isolated from mDCs using the primer set in supplemental Table 1 and inserted into a bidirectional lentiviral expression vector23 downstream of EF1α promoter (LV-miR-155WT). The mutant miR-155 expression lentiviral construct (LV-miR-155MUT) was generated based on LV-miR-155WT sequence with 8 nucleotide mutations in the miR-155 seeding region (see Figure 2C). For construction of luciferase reporter plasmids, 3′-UTRs of the respective mRNAs (KPC1, CD115, and SOCS-1) were cloned into pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (Promega) after amplification of genomic DNA from human mDCs using the primer sets in supplemental Table 1. Mutated 3′-UTRs of respective mRNAs were amplified with the specific primers in which 4 nucleotides at the miRNA seed regions were changed.

Luciferase reporter assays

NIH3T3 cells (2 × 105 cells per well) were plated in 24-well plates with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum one day before transfection. pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vectors (20 ng per well) containing either WT or mutated (MUT) KPC1, CD115, or SOCS-1 3′-UTR, and LV-miR-155WT or LV-miR-155MUT plasmids (800 ng per well) were cotransfected into NIH3T3 cells in triplicate using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested 24 hours later, and luciferase activity was assessed using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Transfection of miRNA precursors or knockdown probes

Pre-miR miRNA precursors for hsa-miR-155, hsa-miR-198, and a negative control (Negative Control #1) were purchased from Ambion. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled miRCURY LNA knockdown probes for hsa-miR-221, hsa-miR-155, hsa-miR-198, and a scramble-miR control were purchased from Exigon. To overexpress or silence miRNAs, imDCs (2.5 × 105 per well) in 24-well plates were transfected with miRNA precursors or miRNA knockdown probes and respective controls at the indicated concentrations for the indicated time using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen).

Western blotting

DCs were harvested, washed, and lysed in 20mM 3-(N-morpholino) propane sulfonic acid buffer containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 2mM ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid, 5mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% Triton X-100, and one complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche Diagnostics) in a 10-mL volume. Membranes were stripped with stripping buffer (0.2M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5, 0.05% Tween-20, 100mM 2-mercaptoethanol) to probe the expression of several specific proteins within one experiment. Each protein sample was separated under reducing conditions on a 4% to 12% polyacrylamide sodium dodecyl sulfate gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Proteins were detected with the primary antibody, mouse-antihuman p27kip1 (BD Biosciences), rabbit-antihuman KPC1,24 rabbit-antihuman SOCS-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or goat-antihuman γ-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Pierce Chemical). Protein quantification was performed using National Institutes of Health Image J software (www.rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

DC-NK coculture assay

imDCs (2.5 × 105 per well) in 24-well plates were transfected with hsa-miR-155 precursors and a negative control at a final concentration of 40nM using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX. Six hours later, DCs were stimulated with the maturation cocktail for 12 hours. Old medium was then removed, and transfected DCs were cocultured with NK cells (5 × 105 cells in 0.5 mL AIM V medium), which were isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells using an NK cell negative isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were cocultured for 24 hours, and the supernatant was harvested for an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay.

ELISA assay

Cell culture supernatants were recovered at the indicated times and evaluated in triplicate for IL-12p70 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) levels using ELISA kits (eBioscience).

Statistical analysis

For non-normally distributed data, the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used in the evaluation of the statistical differences between groups. Two-sample t test was used when the data were approximately normally distributed. For repeated measurement outcomes, a linear mixed model with random subject effect to evaluate miRNA groups and time effects was used (means reported are least square means). An interaction term was introduced in the initial model and removed if it was insignificant. Time was treated as a discrete variable. Groups with values of P ≤ .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Identification of miRNA signatures during DC development and maturation

To systematically investigate miRNA expression profiles during human monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs, monocytes from 2 healthy donors were differentiated into imDCs and matured with IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and PGE2, commonly used in DC clinical trials.25 Total RNA from human monocytes, imDCs, and mDCs was analyzed using a custom miRNA microarray platform.20 Supplemental Figure 1 shows that the difference in miRNA expression between monocytes versus imDCs and monocytes versus mDCs appeared more dramatic than the difference between imDCs versus mDCs, suggesting that miRNA identity between imDCs and mDCs is similar.

Fifty-eight miRNAs whose expression increased more than 1.5-fold or decreased more than 2-fold in comparisons between monocytes and DC maturation subtypes were selected for validation by real-time PCR. Table 1 details the fold change and P values of the differentially expressed miRNAs. The expression levels of 15 miRNAs were decreased more than 2-fold during monocyte differentiation into DCs, and the expression levels of 12 miRNAs were increased more than 2-fold at the imDC and/or mDC stages. Interestingly, all of the miRNAs that were down-regulated at the imDC stage remained at the same level for the mDC stage. Both miRNA-106b-25 (miR-106b, miR-93, and miR-25) and -15/16 (miR-15a and miR-16) clusters were down-regulated during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. miRNA-155 was dramatically up-regulated on DC maturation, although it was only moderately increased in imDCs. miR-198 expression was nearly undetectable in monocytes and imDCs but was clearly increased on DC maturation, whereas conversely miRNA-221 was first up-regulated on monocyte differentiation into imDCs and then down-regulated during DC maturation. These results demonstrate that there are at least 4 types of miRNA signatures during human monocyte development into imDCs and mDCs, suggesting that they may play a pivotal role in DC development, maturation, and function.

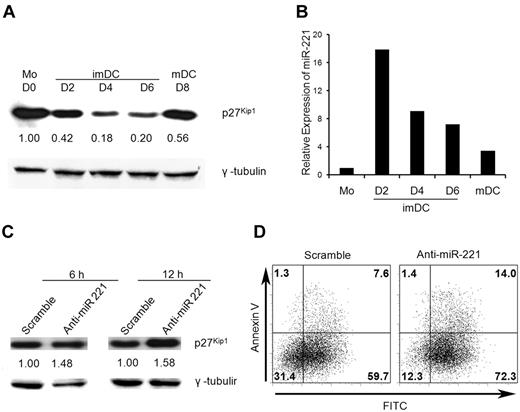

Expression of miR-221 and miR-155 correlates with p27kip1 accumulation

p27kip1 is an inhibitor of cell cycle progression, exerting its effect through interaction with cyclin-dependent kinase complexes and arrestment of cells in G0/1 phase. p27kip1 is present at relatively high levels in quiescent cells and is down-regulated by mitogenic stimulation.26,27 p27kip1 plays a decisive role in nonproliferating cell types, such as eosinophils and DCs.28,29 Because p27kip1 is a direct target of miR-221 in human cancer cells and mast cells,30-32 we investigated whether there was an inverse correlation between p27kip1 and miR-221 expression during human monocyte differentiation into DCs. Human monocytes, differentiating DCs at days 2, 4, and 6, and mDCs were analyzed for expression of p27kip1 and miR-221. As shown in Figure 1A, p27kip1 protein was present at a high level in monocytes. On DC differentiation, p27kip1 expression was progressively down-regulated with the lowest level at the imDC stage. On DC maturation, p27kip1 expression was up-regulated to a level similar to that seen in monocytes. In contrast to p27kip1 expression, miR-221 expression was increased during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and then reduced during DC maturation (Figure 1B; Table 1). miR-221 expression almost disappeared after 4-day maturation (data not shown). To determine whether miR-221 regulates p27kip1 in DCs, imDCs were transfected with an miR-221 inhibitor. As shown in Figure 1C, silencing of miR-221 expression resulted in higher levels of p27kip1 protein expression than scramble controls 6 and 12 hours after transfection, respectively. Consistent with the findings in other cell types,33,34 silencing of miR-221 in imDCs at a time of higher (day 2) or lower (day 4) miR-221 expression levels resulted in modestly increased apoptosis compared with the scrambled control (eg, 16% vs 11% annexin V+ in fluorescein isothiocyanate+ cell populations on day 2 imDCs; Figure 1D; day 4 data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that miR-221 expression was inversely correlated with the expression of p27kip1, suggesting that p27kip1 differential expression during DC development and maturation is at least partially regulated by miR-221.

The effect of miR-221 on p27Kip1 expression and cell apoptosis. (A) p27kip1 expression during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. p27kip1 expression in human monocytes (Mo) at day 0 (D0), imDCs at days 2, 4, and 6, and mDCs at day 8 was analyzed by Western blot. (B) miR-221 expression during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs by real-time PCR analysis. (C) Increased expression of p27kip1 after silencing of miR-221. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-221 knockdown probe (Anti-miR-221) or scramble control (Scramble) at the final concentration of 40nM for the indicated time. Cells were then analyzed for p27kip1 expression by Western blot. (D) Increased apoptosis after silencing of miR-221. imDCs at day 2 or day 4 (data not shown) were transfected with miR-221 knockdown probes or scramble controls (40nM) for 40 hours. Cells were then stained with APC-conjugated annexin V and analyzed on a FACSCalibur. The data shown in every panel are representative of 2 (B-D) or 3 (A) independent experiments.

The effect of miR-221 on p27Kip1 expression and cell apoptosis. (A) p27kip1 expression during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. p27kip1 expression in human monocytes (Mo) at day 0 (D0), imDCs at days 2, 4, and 6, and mDCs at day 8 was analyzed by Western blot. (B) miR-221 expression during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs by real-time PCR analysis. (C) Increased expression of p27kip1 after silencing of miR-221. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-221 knockdown probe (Anti-miR-221) or scramble control (Scramble) at the final concentration of 40nM for the indicated time. Cells were then analyzed for p27kip1 expression by Western blot. (D) Increased apoptosis after silencing of miR-221. imDCs at day 2 or day 4 (data not shown) were transfected with miR-221 knockdown probes or scramble controls (40nM) for 40 hours. Cells were then stained with APC-conjugated annexin V and analyzed on a FACSCalibur. The data shown in every panel are representative of 2 (B-D) or 3 (A) independent experiments.

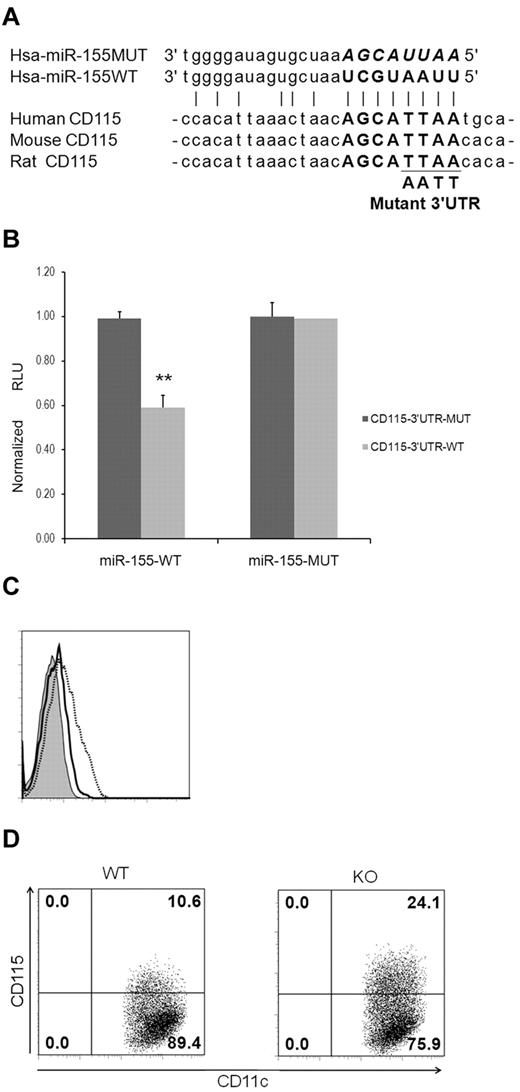

In contrast to miR-221, miR-155 expression positively correlated with p27kip1 expression. miRNA-155 expression was significantly up-regulated on DC maturation, whereas miR-155 expression in monocytes and during differentiation into imDCs at days 2, 4, and 6 was low (Figure 2A). Up-regulation of miR-155 in mDCs was mainly mediated by IL-1β, TNF-α, and PGE2 but probably not IL-6 (Figure 2B). miR-155 is known to target multiple genes, such as PU.1 and SHIP1.15,35 A recent report showed that miR-155 overexpression in the human monocytic leukemia THP-1 cell line depletes the G2 population and accumulates a sub-G1 population, suggesting that miR-155 is involved in cell apoptosis.36 Using the miRGator miRNA target prediction program,37 miR-155 was predicted to target human KPC1, which can recognize free p27kip1 (Figure 2C). KPC1 associates with KPC2, and p27kip1 is then polyubiquitylated. Deletion of KPC1 by miR-155 would result in the inhibition of p27kip1 degradation.24

miR-155 regulates p27kip1 expression by directly targeting KPC1. (A) Expression of miR-155 during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. (B) Effect of the individual component in the maturation cocktail on miR-155 expression. imDCs at day 6 were treated 10 ng/mL of IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α, or 1 μg/mL of PGE2 for 2 days. Relative expression of miRNA-155 was quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to imDCs without treatment. (C) Mature miR-155 sequence (miR-155WT) and mutated miR-155 sequence (miR-155MUT, 8 mutated nt sequences [in italic]) aligned with human and mouse KPC1 3′-UTRs, including miR-155 binding site (in bold). Mutation of miR-155 binding site sequence is shown below. (D) A lucifearse reporter assay to determine targeting of KPC1 3′-UTR by miR-155. The columns represent normalized relative luciferase activity (RLU) by means with 95% confidence intervals from 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (E) Overexpression of miR-155 resulted in decreasing KPC1 and increasing p27kip1 expression. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors and negative controls. Twenty-four hours later, cells were analyzed for KPC1 and p27kip1 expression by Western blot. (F) Reduced KPC1 expression along with up-regulated miR-155 expression during DC maturation. imDCs at day 6 were treated with the maturation cocktail for 2 days (mDC-D2) or 4 days (mDC-D4). Cells were analyzed for miR-155 by real-time PCR and KPC1 expression by Western blot. imDCs at day 6 (imDC) were used as a control. The data shown in each panel are representative of 2 (A,F) or 3 (B,D,E) independent experiments.

miR-155 regulates p27kip1 expression by directly targeting KPC1. (A) Expression of miR-155 during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. (B) Effect of the individual component in the maturation cocktail on miR-155 expression. imDCs at day 6 were treated 10 ng/mL of IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α, or 1 μg/mL of PGE2 for 2 days. Relative expression of miRNA-155 was quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to imDCs without treatment. (C) Mature miR-155 sequence (miR-155WT) and mutated miR-155 sequence (miR-155MUT, 8 mutated nt sequences [in italic]) aligned with human and mouse KPC1 3′-UTRs, including miR-155 binding site (in bold). Mutation of miR-155 binding site sequence is shown below. (D) A lucifearse reporter assay to determine targeting of KPC1 3′-UTR by miR-155. The columns represent normalized relative luciferase activity (RLU) by means with 95% confidence intervals from 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (E) Overexpression of miR-155 resulted in decreasing KPC1 and increasing p27kip1 expression. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors and negative controls. Twenty-four hours later, cells were analyzed for KPC1 and p27kip1 expression by Western blot. (F) Reduced KPC1 expression along with up-regulated miR-155 expression during DC maturation. imDCs at day 6 were treated with the maturation cocktail for 2 days (mDC-D2) or 4 days (mDC-D4). Cells were analyzed for miR-155 by real-time PCR and KPC1 expression by Western blot. imDCs at day 6 (imDC) were used as a control. The data shown in each panel are representative of 2 (A,F) or 3 (B,D,E) independent experiments.

To definitively validate KPC1 as a target of miR-155, the full-length KPC1 3′-UTR was cloned and inserted downstream of the luciferase gene in the pmirGLO expression vector (pGL-KPC1-WT). The 3′-UTR of KPC1 with a mutant sequence in the miR-155 predicted binding site was cloned and inserted into the pmirGLO vector as a negative control (pGL-KPC1-MUT). NIH3T3 cells were cotransfected with LV-miR-155WT (or LV-miR-155MUT) and pGL-KPC1-WT (or pGL-KPC1-MUT). Ectopic expression of miR-155 resulted in an appreciable repression of the luciferase reporter activity by targeting KPC1 WT but not the mutant 3′-UTR, whereas mutant miR-155 did not affect luciferase reporter activity with the intact or mutant KPC1 3′-UTR (Figure 2D). These results suggest that the KPC1 is a direct target of miR-155.

To further investigate whether miR-155 regulates p27kip1 expression in DCs, imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors or negative controls for 24 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of KPC1 and p27kip1 by Western blot. As shown in Figure 2E, KPC1 expression was reduced and p27kip1 was increased after overexpression of miR-155 in imDCs. In addition, KPC1 expression was reduced along with miR-155 up-regulation during DC maturation (Figure 2F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that miR-155 indirectly regulates p27kip1 expression by targeting KPC1.

miR-155 induces DC apoptosis

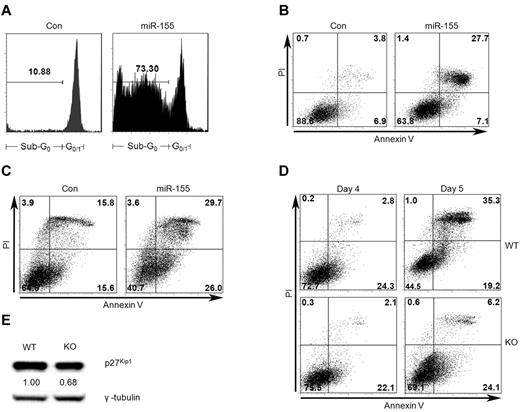

Because up-regulation of p27kip1 is not only linked to cell cycle arrest, but also associated with apoptosis,28,29 we wanted to determine whether overexpression of miR-155 could induce apoptosis in DCs. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors or negative controls. Indeed, overexpression of miR-155 in imDCs for 24 hours induced the typical characteristics of apoptosis as demonstrated by an increased sub-G0 fraction (73% vs 11% in the control group; Figure 3A) and annexin V+PI+ populations (28% vs 4%; Figure 3B). Overexpression of miRNA-155 in mDCs also led to transition from apoptosis to necrosis (30% vs 16% of annexin V+PI+ populations; Figure 3C). To further confirm the relationship between miR-155 expression and apoptosis, BM-derived DCs were generated from WT and miR-155−/− mice and stimulated with LPS. Up to day 4 after LPS maturation, there was no significant difference in DC apoptosis between WT and miR-155−/− mice. However, on day 5, apoptotic populations were dramatically increased in DCs from WT versus miR-155−/− mice (Figure 3D). Nearly all WT DCs died on day 6 after LPS stimulation, although most of miR-155−/− DCs still survived for one additional week (data not shown). Consistently, mDCs from WT mice had higher level of p27kip1 than that from miR-155−/− mice (Figure 3E). These data indicate the regulatory role of the miR-155-KPC1-p27kip1 pathway in DC apoptosis.

miR-155 modulates DC apoptosis. (A-B) Forced overexpression of miR-155 induced imDCs to undergo apoptosis. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors and negative controls at the final concentration of 40nM for 24 hours. Cells were analyzed for apoptosis by staining with PI (A) or APC-annexin V (B) to detect percentage of sub-G0 fraction and apoptosis. (C) Induction of apoptosis in mDCs after overexpression of miR-155. (D) Less apoptosis in activated DCs from miR-155−/− mice than DCs from WT mice. Murine imDCs were generated from BM cells and purified by anti-CD11c microbeads. Purified imDCs (2.5 × 105 per well) were then cultured in 24-well plates in the presence of murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL). Cells were watched every day under an inverted microscope. At days 4 and 5, cells were collected and stained with APC-annexin V and PI for analysis of apoptosis. (E) Less p27kip1 expression in activated DCs from miR-155−/− mice than WT DCs. Activated mDCs by LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 days were analyzed for p27kip1 expression by Western blot. The data shown in every panel are representative of 2 (D) or 3 (A-C,E) independent experiments.

miR-155 modulates DC apoptosis. (A-B) Forced overexpression of miR-155 induced imDCs to undergo apoptosis. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors and negative controls at the final concentration of 40nM for 24 hours. Cells were analyzed for apoptosis by staining with PI (A) or APC-annexin V (B) to detect percentage of sub-G0 fraction and apoptosis. (C) Induction of apoptosis in mDCs after overexpression of miR-155. (D) Less apoptosis in activated DCs from miR-155−/− mice than DCs from WT mice. Murine imDCs were generated from BM cells and purified by anti-CD11c microbeads. Purified imDCs (2.5 × 105 per well) were then cultured in 24-well plates in the presence of murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL). Cells were watched every day under an inverted microscope. At days 4 and 5, cells were collected and stained with APC-annexin V and PI for analysis of apoptosis. (E) Less p27kip1 expression in activated DCs from miR-155−/− mice than WT DCs. Activated mDCs by LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 days were analyzed for p27kip1 expression by Western blot. The data shown in every panel are representative of 2 (D) or 3 (A-C,E) independent experiments.

miR-155 targets CD115 but has no effect on HLA and costimulatory molecule expression in DCs

Because miR-155 and miR-198 were dramatically up-regulated in mDCs (Table 1), we hypothesized that these 2 miRNAs may influence DC maturation. To test this, DCs were transfected with miRNA-155 and miRNA-198 knockdown probes to silence endogenous cognate miRNAs. Analysis of DC surface molecules, including CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II, revealed no difference in expression compared with scramble-treated DCs before and after maturation (Figure 4A-B). To further confirm these results in mice, BM-derived imDCs were generated from miR-155−/− and WT mice and matured with LPS. Flow cytometric analysis of major histocompatibility complex class II and costimulatory molecule levels in imDCs and mDCs indicated no differences in expression between miR-155−/− and WT mice (Figure 4C-D). Taken together, these results indicate that miR-155 (and miR-198) has no impact on HLA and costimulatory molecule expression in DCs.

Silencing of miRNA-155 has no effect on HLA and costimulatory molecule expression in DCs. (A-B) Silencing of miRNA-155 in imDCs (A) and mDCs (B) did not affect HLA and costimulatory molecule expression. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with anti-miR-155, anti-miR-221 knockdown probes, or scramble probe controls. Two days later, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (A). imDCs at day 6 were transfected with anti-miR-155, anti-miR-198 knockdown probes, or scramble probes followed by the maturation cocktail for 24 hours. Cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (B). x- and y-axes indicate fluorescein isothiocyanate (probe) and antibody intensity, respectively. (C-D) Deletion of miRNA-155 in DCs did not affect major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecule expression in murine imDCs and mDCs. CD11c+ cells were gated for analysis of expression of major histocompatibility complex class II or costimulatory molecules (C). BM-derived imDCs at day 6 were further treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed as in Figure 4C (D). Black dotted line indicates DCs from WT mice; solid gray line, DCs from miR-155−/− (knockout [KO]) mice; and tinted line, isotope control. The data shown in every panel are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Silencing of miRNA-155 has no effect on HLA and costimulatory molecule expression in DCs. (A-B) Silencing of miRNA-155 in imDCs (A) and mDCs (B) did not affect HLA and costimulatory molecule expression. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with anti-miR-155, anti-miR-221 knockdown probes, or scramble probe controls. Two days later, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (A). imDCs at day 6 were transfected with anti-miR-155, anti-miR-198 knockdown probes, or scramble probes followed by the maturation cocktail for 24 hours. Cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (B). x- and y-axes indicate fluorescein isothiocyanate (probe) and antibody intensity, respectively. (C-D) Deletion of miRNA-155 in DCs did not affect major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecule expression in murine imDCs and mDCs. CD11c+ cells were gated for analysis of expression of major histocompatibility complex class II or costimulatory molecules (C). BM-derived imDCs at day 6 were further treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed as in Figure 4C (D). Black dotted line indicates DCs from WT mice; solid gray line, DCs from miR-155−/− (knockout [KO]) mice; and tinted line, isotope control. The data shown in every panel are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

In contrast, CD115, a marker of terminal maturation of DCs, was found to be a target of miR-155 (Figure 5A). Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated that cotransfection of the intact CD115 3′-UTR with LV-miR-155WT resulted in a significant repression of the luciferase reporter activity. As a control, LV-miR-155MUT did not affect luciferase expression with the intact and mutant CD115 3′-UTR (Figure 5B). More importantly, forced overexpression of miR-155 in imDCs resulted in a decrease of CD115 expression on the cell surface (Figure 5C). Consistent with this, miR-155−/− mDCs exhibited higher levels of CD115 than WT cells (Figure 5D). These results suggest that CD115 is a direct target of miR-155.

CD115 is a target of miR-155. (A) Multiple species sequence alignment of the CD115 3′-UTR, including the predicted miR155 target site sequence (in bold). Mutation of the miR155 target site sequence is shown below. (B) Luciferase reporter assays to confirm targeting of CD115 3′-UTR by miR-155. The data are means with 95% confidence intervals from 2 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (C) Forced overexpression of miR-155 down-regulated CD115 expression in imDCs. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors (black solid line) or negative controls (dotted gray line) for 24 hours. Cells were then stained with an isotype control antibody (tinted) or anti-CD115. (D) Higher levels of CD115 expression in DCs from miR-155−/− (KO) mice after LPS stimulation. BM-derived imDCs from WT and KO mice were purified with anti-CD11c microbeads and stimulated with LPS (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed for CD115 expression by flow cytometric analysis.

CD115 is a target of miR-155. (A) Multiple species sequence alignment of the CD115 3′-UTR, including the predicted miR155 target site sequence (in bold). Mutation of the miR155 target site sequence is shown below. (B) Luciferase reporter assays to confirm targeting of CD115 3′-UTR by miR-155. The data are means with 95% confidence intervals from 2 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (C) Forced overexpression of miR-155 down-regulated CD115 expression in imDCs. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors (black solid line) or negative controls (dotted gray line) for 24 hours. Cells were then stained with an isotype control antibody (tinted) or anti-CD115. (D) Higher levels of CD115 expression in DCs from miR-155−/− (KO) mice after LPS stimulation. BM-derived imDCs from WT and KO mice were purified with anti-CD11c microbeads and stimulated with LPS (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed for CD115 expression by flow cytometric analysis.

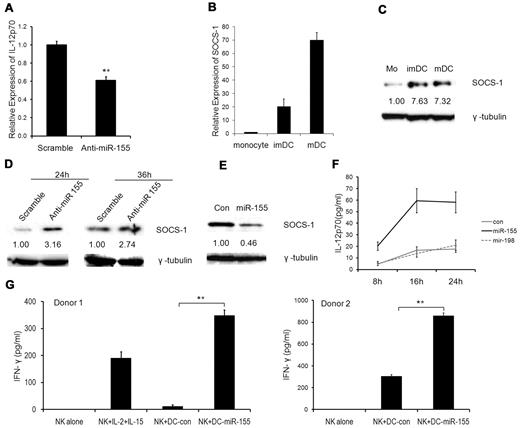

miR-155 modulates IL-12p70 production in mDCs and enhances IFN-γ production by NK cells

Next, we investigated whether miR-155 regulates cytokine production in DCs. We found that IL-12p70 (Figure 6A) and IL-10 (data not shown) production was significantly reduced after miRNA-155 silencing during DC maturation. Consistent with this, activated DCs from miR-155−/− mice secreted less IL-12p70 than those from WT mice (supplemental Figure 2). IL-12p70 produced by DCs plays an important role in the development of IFN-γ-producing T cells and NK-cell activation.1 Several studies have shown that IL-12 production in DCs was related to SOCS-1 expression.38,39 During human monocyte differentiation into DCs, SOCS-1 expression at mRNA level was up-regulated and reached its highest level at maturation stage (Figure 6B). However, the expression of SOCS-1 at protein level was not elevated along with the mRNA level on DC maturation (Figure 6C), suggesting that SOCS-1 was post-transcriptionally regulated. SOCS-1 has been shown to be regulated by miR-155 in murine T regulatory cells.40 We also confirmed that human SOCS-1 was a direct target of miRNA-155 in a luciferase report assay (supplemental Figure 3). Consistent with this, silencing of miR-155 in mDCs resulted in increased SOCS-1 expression at protein level (Figure 6D), whereas forced expression of miR-155 led to reduced SOCS-1 expression in imDCs (Figure 6E).

miR-155 modulates IL-12p70 production in mDCs and enhances IFN-γ production by NK cells. (A) Reduction of IL-12p70 secretion by mDCs after miR-155 silencing. imDCs at day 6 were transfected with anti-miR-155 knockdown probes and scramble probes. Six hours later, cells were treated with the maturation cocktail for another 24 hours. Supernatant was harvested and IL-12p70 was measured by ELISA. The data shown are means with 95% confidence intervals from 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (B-C) SOCS-1 expression in human monocytes, imDCs, and mDCs by real-time PCR (B) and Western blot (C). (D) SOCS-1 expression in DCs after miR-155 silencing by Western blot. imDCs at day 6 were transfected with 80nM of scramble and miR-155 KO probes for the indicated time. Cells were analyzed for SOCS-1 expression by Western blot. (E) SOCS-1 expression in imDCs after miR-155 overexpression. imDCs at day 5 were transfected with 40nM of miR-155 precursors for 24 hours and then analyzed by Western blot. (F) Overexpression of miR-155 in DCs increased IL-12p70 secretion. imDCs at day 6 were transfected with 40nM of miR-155 or miR-198 precursors or negative controls. Six hours later, cells were treated with the maturation cocktail for another 8, 16, and 24 hours. Supernatants were harvested, and IL-12p70 was measured by ELISA. The data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. A linear mixed model with random subject effect was used to evaluate miRNA groups and time effects. There was a significant difference between the miR-155 and other groups (P < .01). (G) imDCs at day 6 were transfected with 40nM of miR-155 precursors or negative controls. Six hours later, cells were treated with the maturation cocktail for another 12 hours. After washing, DCs were cocultured with autologous NK cells at the ratio of 1:2 for 24 hours. Supernatants were harvested, and IFN-γ was measured by ELISA. The data are from 2 independent experiments with 2 different donors. Values represent the mean ± SD. **P < .01 by Student t test.

miR-155 modulates IL-12p70 production in mDCs and enhances IFN-γ production by NK cells. (A) Reduction of IL-12p70 secretion by mDCs after miR-155 silencing. imDCs at day 6 were transfected with anti-miR-155 knockdown probes and scramble probes. Six hours later, cells were treated with the maturation cocktail for another 24 hours. Supernatant was harvested and IL-12p70 was measured by ELISA. The data shown are means with 95% confidence intervals from 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (B-C) SOCS-1 expression in human monocytes, imDCs, and mDCs by real-time PCR (B) and Western blot (C). (D) SOCS-1 expression in DCs after miR-155 silencing by Western blot. imDCs at day 6 were transfected with 80nM of scramble and miR-155 KO probes for the indicated time. Cells were analyzed for SOCS-1 expression by Western blot. (E) SOCS-1 expression in imDCs after miR-155 overexpression. imDCs at day 5 were transfected with 40nM of miR-155 precursors for 24 hours and then analyzed by Western blot. (F) Overexpression of miR-155 in DCs increased IL-12p70 secretion. imDCs at day 6 were transfected with 40nM of miR-155 or miR-198 precursors or negative controls. Six hours later, cells were treated with the maturation cocktail for another 8, 16, and 24 hours. Supernatants were harvested, and IL-12p70 was measured by ELISA. The data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. A linear mixed model with random subject effect was used to evaluate miRNA groups and time effects. There was a significant difference between the miR-155 and other groups (P < .01). (G) imDCs at day 6 were transfected with 40nM of miR-155 precursors or negative controls. Six hours later, cells were treated with the maturation cocktail for another 12 hours. After washing, DCs were cocultured with autologous NK cells at the ratio of 1:2 for 24 hours. Supernatants were harvested, and IFN-γ was measured by ELISA. The data are from 2 independent experiments with 2 different donors. Values represent the mean ± SD. **P < .01 by Student t test.

Because silencing of miR-155 resulted in decreased levels of IL-12p70 in mDCs, we predicted that overexpression of miR-155 in mDCs could enhance IL-12p70 secretion. To test this, imDCs at day 6 were transfected with miR-155, miR-198 precursors, or a negative control followed by incubation with the maturation cocktail 6 hours after transfection. Indeed, miR-155 overexpression in mDCs led to significantly high levels of IL-12p70 secretion at 8, 16, and 24 hours after transfection (P < .01), whereas overexpression of miR-198 in mDCs or negative control-transfected mDCs had little effect on IL-12p70 production (Figure 6F). Moreover, enhanced IL-12 production by overexpression of miR-155 was demonstrated using more potent IL-12 inducers, including LPS plus R484 and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid plus the cocktail (supplemental Figure 4).

To investigate whether overexpression of miR-155 could enhance mDCs in activating NK cells, mDCs with overexpression of miR-155 were cocultured with autologous CD3−CD56+ NK cells. As shown in Figure 6G, NK cells cocultured with mDCs that were transfected with miR-155 precursors secreted significant higher levels of IFN-γ than control cultures (P < .01), suggesting that miRNA-155 overexpression can enhance the ability of mDCs to activate NK-cell production of IFN-γ.

Discussion

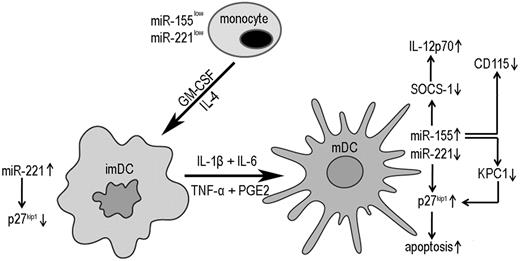

In this study, we comprehensively analyzed miRNA profiles in human monocytes, imDCs, and mDCs and demonstrated the following novel observations. First, we identified 4 types of miRNA signatures during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs (Table 1). Second, we revealed the cooperatively regulatory role of miR-221 and miR-155 in human DC development and apoptosis through modulation of p27kip1 expression (Figure 7). miR-221 directly targets p27kip1, whereas miR-155 indirectly modulates p27kip1 via targeting KPC1. Third, our data indicate that overexpression of miR-155 in mDCs led to higher levels of IL-12p70 secretion by DCs, enchancing IFN-γ production by NK cells (Figure 6).

Cooperative regulation of miR-221 and miR-155 during human monocyte differentiation into DCs. In nonproliferating human monocytes, miR-221 and miR-155 are expressed at a relatively low level, accompanied by relatively high levels of p27kip1. When monocytes differentiate into imDCs by GM-CSF and IL-4, miR-221 is up-regulated, resulting in down-regulation of p27kip1, which leads to imDC development. During DC maturation, miR-155 is up-regulated, which promotes IL-12p70 production and DC terminal differentiation by inhibiting the expression of SOCS-1 and CD115, respectively. miR-155 also targets KPC1, which promotes p27kip1 degradation. Accompanied by miR-155 up-regulation, miR-221 is down-regulated, resulting in p27kip1 accumulation and eventual DC apoptosis.

Cooperative regulation of miR-221 and miR-155 during human monocyte differentiation into DCs. In nonproliferating human monocytes, miR-221 and miR-155 are expressed at a relatively low level, accompanied by relatively high levels of p27kip1. When monocytes differentiate into imDCs by GM-CSF and IL-4, miR-221 is up-regulated, resulting in down-regulation of p27kip1, which leads to imDC development. During DC maturation, miR-155 is up-regulated, which promotes IL-12p70 production and DC terminal differentiation by inhibiting the expression of SOCS-1 and CD115, respectively. miR-155 also targets KPC1, which promotes p27kip1 degradation. Accompanied by miR-155 up-regulation, miR-221 is down-regulated, resulting in p27kip1 accumulation and eventual DC apoptosis.

Our study is the first to demonstrate the differential expression of p27kip1 during human monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. Previous studies have shown that p27kip1 levels are regulated by alterations of protein stability.41 The degradation of p27Kip1 is regulated by 2 distinct mechanisms: translocation-coupled cytoplasmic ubiquitination by KPC and nuclear ubiquitination by Skp2.24 The third new mechanism identified here is post-transcriptional regulation of p27kip1 by miRNAs. p27kip1 regulation by miR-221 has been reported in several types of cells, including cancer cells and mast cells.30-32 Our current study confirmed this finding in human DCs (Figure 1). Furthermore, we have identified KPC1 as a novel target by miR-155 in human DCs, which indirectly regulate p27kip1 (Figure 2). KPC, a ubiquitin ligase, consisting of KPC1 and KPC2, recognizes free p27kip1 via the NH2-terminal region and then polyubiquitinate p27kip1 for proteasome-mediated degradation by the COOH-terminal RING-finger domain of KPC1.24 It appears that miR-155 functions like a tumor suppressor in DCs via its indirect effects on p27kip1 stability, although it is oncogenic in other types of cells and tissues, including B-cell, myeloid cell, breast, lung, colon, pancreatic, and thyroid tissues.42 It may be possible that the miR-155-KPC1-p27kip1 pathway is defective in tumors.

There are many putative functions attributed to p27kip1, including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.41 Although the role of p27kip1 in nonproliferating cells has not been well investigated, one study in DCs suggested that increased p27kip1 expression (eg, recombinant adenovirus infection) promotes apoptosis.29 Consistent with this finding, an increase of apoptosis was found in imDCs when miR-221 was silenced (Figure 1D) or miR-155 was overexpressed (Figure 3A-B), suggesting that a low level of p27kip1 expression is necessary for imDC development. Overexpression of miR-155 in mDCs also led to an increase in apoptosis (Figure 3C). It was further confirmed that mDCs from miR-155−/− mice survived longer than WT mDCs (Figure 3D). These results provide the first evidence that miRNAs are critical regulators in DC apoptosis.

DC apoptosis is physiopathologically essential in controlling tolerance and immunity.43 The most convincing evidence demonstrating a central role for DCs in maintaining self-tolerance is that blocking DC apoptosis in mice leads to DC buildup and the development of systemic autoimmune diseases.44 Consistent with this, DCs in autoimmune patients with mutations in caspase 10, an enzyme activated during apoptosis, are less apoptotic and hence accumulate.45 In addition, it has been recently shown that uptake of apoptotic DCs induces immature DCs to secrete TGF-β, which in turn promotes the differentiation of naive T cells into regulatory T cells.46 Furthermore, constitutive ablation of DCs breaks self-tolerance and results in spontaneous fetal autoimmunity.47 Therefore, down-regulated miR-221 and up-regulated miRNA-155 expression during DC maturation by various stimuli, resulting in p27kip1 accumulation in mDCs and subsequent DC apoptosis, could be physiologically important.

DCs are a major source of many cytokines, including IL-12, which is considered as a critical third signal for naive CD8 T-cell activation, strong effector cell function, and memory T-cell formation.48 SOCS-1, an inducible negative feedback inhibitor of JAK/STAT signal pathway, functions like an antigen presentation attenuator in DCs through limiting IL-12 production.38,39 In this study, we demonstrate that IL-12 production by human DCs is regulated by miR-155-mediated targeting of SOCS-1. Of note, the finding that SOCS-1 is a target of miR-155 has been previously reported in murine T regulatory cells and more recently in breast cancer cell lines and murine DCs.13,40,42 Nevertheless, enhanced production of IL-12 by DCs or IFN-γ by NK cells via overexpression of miR-155 in mDCs suggests that miR-155 could be used as an adjuvant to improve DC vaccines.

In conclusion, we have identified differentially expressed miRNAs during human monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. More importantly, we have uncovered the important role of miR-221 and miR-155 in DC apoptosis and IL-12 production. Whether these miRNAs are critical regulators in human DC development and function in vivo remains to be investigated. Our finding that miRNAs are involved in regulation of DC survival and cytokine production may provide additional knowledge about miRNA regulation in DC biology and implicate modulation DCs using miRNAs for clinical applications.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank University of Minnesota Supercomputing Institute for microarray data acquisition. K.R. is a Directed Research undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota, College of Biologic Sciences.

This work was supported by startup funds from the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center and Department of Pediatrics, the Children's Cancer Research Fund in Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Medical School Dean's Commitment, and in part by grants from the Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, the Gabrielle's Angel Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research Kimmel Scholar Program (X. Zhou).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: C.L. designed the research, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; X.H., X. Zhang, and K.R. performed the research; Q.C. performed statistical analyses; K.I.N. provided critical reagents and edited the paper; B.R.B discussed the work and edited the paper; Y.Z. discussed the work and wrote the paper; and X. Zhou oversaw the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Xianzheng Zhou, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, MMC 366, 420 Delaware St, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: zhoux058@umn.edu.

![Figure 2. miR-155 regulates p27kip1 expression by directly targeting KPC1. (A) Expression of miR-155 during monocyte differentiation into imDCs and mDCs. (B) Effect of the individual component in the maturation cocktail on miR-155 expression. imDCs at day 6 were treated 10 ng/mL of IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α, or 1 μg/mL of PGE2 for 2 days. Relative expression of miRNA-155 was quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to imDCs without treatment. (C) Mature miR-155 sequence (miR-155WT) and mutated miR-155 sequence (miR-155MUT, 8 mutated nt sequences [in italic]) aligned with human and mouse KPC1 3′-UTRs, including miR-155 binding site (in bold). Mutation of miR-155 binding site sequence is shown below. (D) A lucifearse reporter assay to determine targeting of KPC1 3′-UTR by miR-155. The columns represent normalized relative luciferase activity (RLU) by means with 95% confidence intervals from 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 by 2 sample t test. (E) Overexpression of miR-155 resulted in decreasing KPC1 and increasing p27kip1 expression. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with miR-155 precursors and negative controls. Twenty-four hours later, cells were analyzed for KPC1 and p27kip1 expression by Western blot. (F) Reduced KPC1 expression along with up-regulated miR-155 expression during DC maturation. imDCs at day 6 were treated with the maturation cocktail for 2 days (mDC-D2) or 4 days (mDC-D4). Cells were analyzed for miR-155 by real-time PCR and KPC1 expression by Western blot. imDCs at day 6 (imDC) were used as a control. The data shown in each panel are representative of 2 (A,F) or 3 (B,D,E) independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/16/10.1182_blood-2010-12-322503/4/m_zh89991169770002.jpeg?Expires=1767927399&Signature=GblwVPrukSUGWKLKGQGwVr0s5~lOHnD~E7uK-al2zfbC9i-e~-aGVEQuTRxBx-e2QbjMSaGjiaRwy2BzClyIQCm7~ts1-o8kR5hYxQEUBhuafXz~h5rkScOOdXQW2I2PaYCCMwMXUGf1cdmxXUK8t2CFChmKBxNHxGoL8QDEv6A2NwhCQa7trcQeK2GAOi~QeMaj-IDF0C14vRnj7anpJzHtuGV2IuvEjEJfacF3ogOzLxiJpoiE~iBGLQEcMtFefPWRL4fbZy96eN4chM2K9oIwGAofPbLCaugJ8oXGt9fOakKH3P8T6x4-Gbr0dQXoZFBi1ekWImqEn9Kodh8Igg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Silencing of miRNA-155 has no effect on HLA and costimulatory molecule expression in DCs. (A-B) Silencing of miRNA-155 in imDCs (A) and mDCs (B) did not affect HLA and costimulatory molecule expression. imDCs at day 4 were transfected with anti-miR-155, anti-miR-221 knockdown probes, or scramble probe controls. Two days later, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (A). imDCs at day 6 were transfected with anti-miR-155, anti-miR-198 knockdown probes, or scramble probes followed by the maturation cocktail for 24 hours. Cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (B). x- and y-axes indicate fluorescein isothiocyanate (probe) and antibody intensity, respectively. (C-D) Deletion of miRNA-155 in DCs did not affect major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecule expression in murine imDCs and mDCs. CD11c+ cells were gated for analysis of expression of major histocompatibility complex class II or costimulatory molecules (C). BM-derived imDCs at day 6 were further treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed as in Figure 4C (D). Black dotted line indicates DCs from WT mice; solid gray line, DCs from miR-155−/− (knockout [KO]) mice; and tinted line, isotope control. The data shown in every panel are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/16/10.1182_blood-2010-12-322503/4/m_zh89991169770004.jpeg?Expires=1767927399&Signature=uj6oeE9HRENkYlhv1NkdVIlERXHEcL~40RWUUDyy0VzfQ0CxkNbrzNqU74GlcuLxNpIkUjSCuwXmSrEwLEZ6sE9FCTssJ8LkQOuxAnnbDCDDy5qNxNB-shZ3jI1yzMrqWPCoe~K7AvnEuKjY-xnqZj6uJiHAVLVg~6wNnkTSHLKE20USuO045v4K~Ii0Xv-OF3kucjqCRVZ05wXiGf3-cSl3Oxatp3-F2LZQSDnCb3Mg8i1KexIiKXjWSTHALhWCbOX8uuzLI7MK1LBJwPnjTye111IdASBiZL~gnZCFxc0LSudzLzyArOu~AqzIE5YFWNy0H53ZSf9F2pWKWEIxJw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)