In this issue of Blood, Sutton et al report the results of a randomized clinical trial exploring the role of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), showing that transplantation may increase the response rate and prolong the time to progression but that this does not result in a longer survival in comparison with chemotherapy treatment.1

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is a frequent form of leukemia with heterogeneous biology and clinical course. Despite considerable progress in its treatment, CLL remains incurable. Because of this, and in common with many other hematologic malignancies with no effective therapy, ASCT has been used in an attempt to improve patients outcome. In the early 1990s some studies reported encouraging results and raised hope that this procedure could be useful in CLL.2 This promoted additional phase 2 studies and retrospective analyses trying to shed light on the usefulness of ASCT in CLL. In addition, many patients with CLL were offered ASCT outside clinical studies in the belief that the procedure could be useful. Initial enthusiasm, however, was soon tempered because the observed results demonstrated no plateau in either event-free or overall survival.

Nevertheless, the acid test for any treatment procedure is randomized clinical trials, which have been long awaited for ASCT in CLL. In addition to the paper by Sutton and colleagues in this edition, Blood has recently published another similar trial.3 Thus, results of ASCT in CLL from 2 randomized trials are finally available, and the authors of these studies have to be commended for having undertaken a necessary but difficult task.

The main conclusions that can be drawn from these studies confirm current notions about ASCT in CLL: (1) Whereas the event-free and progression-free survival are longer in patients who receive a transplant, unfortunately, this does not translate into improved overall survival. (2) The negative impact of biomarkers that confer resistance to conventional therapy (eg, TP53 aberrations) are not overcome by autografts, which is not surprising if one considers that ASCT is simply chemotherapy by another name. This is in contrast with allogeneic stem transplantation, which actually overcomes poor prognostic markers.4 (3) Patients who gain the highest benefit from autologous transplantation (ie, young subjects with low tumor mass, responding very well to therapy and no unfavorable prognostic factors) are also those most likely to respond to conventional therapy and to have prolonged control of their disease and long survival. And (4) ASCT is not effective as salvage therapy. In fact, allogeneic stem transplantation should be considered as a treatment possibility in any patient failing chemoimmunotherapy.5-7

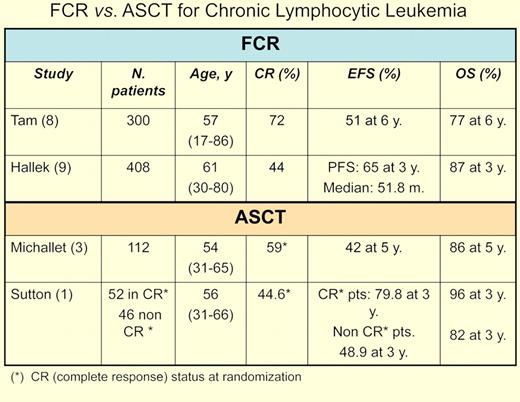

Finally, the upfront therapy in these studies, although reasonable when planned, is suboptimal by current standards. In the past few years, studies led by Keating and coworkers at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center have placed chemoimmunotherapy, namely the combination of FCR (ie, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab) at center stage for CLL therapy.8 Importantly, the superiority of FCR over FC as initial therapy in CLL was confirmed in a randomized trial conducted by the German CLL Study Group.9 As a result, FCR is the new benchmark for any study trying to demonstrate an improvement in CLL therapy.

The question that has to be asked today is whether the results obtained by Sutton, Michallet, and their respective colleagues would have been different if FCR had been used.1,3 In phase 2 studies from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, patients who received a transplant after FCR in the final phase of the study had inferior outcome to those patients who were selected on the basis of their response to less aggressive chemotherapy.10 Moreover, further ASCT randomized trials in CLL are difficult to envision in an era in which, in contrast with 15 years ago, effective therapies for this form of leukemia exist, with newer and hopefully yet more effective therapies being investigated or in the horizon.

Whereas great caution must be taken comparing the outcome of separate studies, it would appear that the outcomes in terms of event-free-survival and overall survival are similar for patients treated with FCR and those receiving ASCT (see table).

It seems, therefore, that the game for ASCT in CLL is indeed over. It remains to be seen whether other forms of cellular therapy (eg, manipulated autologous T cells) can eventually be effective or offer some additional, positive effect to current or forthcoming chemoimmunotherapy regimens.11

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■