Abstract

Major contributions to research in hematopoiesis in invertebrate animals have come from studies in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, and the freshwater crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus. These animals lack oxygen-carrying erythrocytes and blood cells of the lymphoid lineage, which participate in adaptive immune defense, thus making them suitable model animals to study the regulation of blood cells of the innate immune system. This review presents an overview of crustacean blood cell formation, the role of these cells in innate immunity, and how their synthesis is regulated by the astakine cytokines. Astakines are among the first invertebrate cytokines shown to be involved in hematopoiesis, and they can stimulate the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of hematopoietic tissue cells. The astakines and their vertebrate homologues, prokineticins, share similar functions in hematopoiesis; thus, studies of astakine-induced hematopoiesis in crustaceans may not only advance our understanding of the regulation of invertebrate hematopoiesis but may also provide new evolutionary perspectives about this process.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is a complex process by which different blood cells are formed and are released from hematopoietic tissues, and this process has been studied extensively in vertebrates. Among the vertebrate blood cells, granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages are mainly involved in innate immune responses and tissue repair, and cells with similar morphologic and functional characteristics can be found in most metazoans. In coelomate invertebrates, these blood cells usually are referred to as hemocytes. Because of their lack of oxygen-carrying erythrocytes and blood cells of the lymphoid lineage, which participate in adaptive immune defense, hematopoiesis in invertebrates offers a simple model system to study the regulation of the blood cells of the innate immune system.

Many invertebrates have a long life span (for example, lobsters, crabs, and mollusks) and are dependent on the continuous synthesis of blood cells in contrast to short-lived invertebrates such as some insects. The freshwater crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus, can live up to 20 years and contains separate hematopoietic tissue (HPT) in which renewal of stem cells and the synthesis of new hemocytes occur continuously throughout the lifetime of the animal. The hematopoietic tissue in P leniusculus has been well described; thus, this animal provides a good opportunity to study hematopoiesis in adult invertebrates in contrast to, for example, Drosophila melanogaster, where hematopoietic activity only occurs at the embryonic and larval stages and not at the adult stage. HPT from P leniusculus can be easily isolated and studied in vitro, either as intact tissue or by isolating and culturing its individual cells. This technique is unique among invertebrate animals and has enabled researchers to perform detailed studies of regulatory proteins involved in hemocyte development. Recent advances with the use of this crayfish cell culture system have revealed the importance of a new group of cytokines named astakines, which are present in the genomes of some invertebrates but not in the invertebrate model organisms Drosophila or Caenorhabditis elegans. This review will focus on crustacean hematopoiesis and the importance of this new group of cytokines, which have similarities to vertebrate prokineticins (PROKs).

Blood cells (hemocytes) in crustaceans and their role in immunity

Arthropods have an open circulatory system, with a poorly developed cardiovascular system in insects and a highly developed cardiovascular system in crustaceans. The crustacean vascular system should be classified as “incompletely closed” rather than “open.” In crustaceans, the circulatory system is used for oxygen transport via oxygen transport pigments of the hemocyanin protein family, which are present in plasma and not in cells. The crustacean circulatory system is also loaded with cells involved in protecting the animal from invading organisms and wound healing. Similar to other invertebrates, crustaceans lack a true adaptive immune response and, therefore, have to rely on very efficient innate immune mechanisms in which these blood cells (hemocytes) play a key role. Melanization and coagulation are rapid immune reactions in invertebrates and are mediated by hemocytes in response to microbial polysaccharides.

The original findings regarding invertebrate innate immunity were performed in freshwater crayfish, among which the proteolytic cascade that controls melanization, the so-called prophenoloxidase-activating system (proPO), is one of the most important. This system, in which the zymogenic prophenoloxidase is activated by a cascade of proteinases, leading to activity of phenoloxidase and subsequent melanin formation, has a sensitivity similar to the clotting system of horseshoe crabs1 and will become activated by < 10 pg of microbial polysaccharide. It has recently been shown that the proteolytic cascade responsible for activation of the proPO system and the cascade leading to Toll activation is the same in the insect Tenebrio molitor.2 The proPO system is an innate immune process that promotes melanization, and the Toll pathway leads to production of antimicrobial peptides. These findings demonstrate the complexity of invertebrate immunity.

Because of the fact crustaceans have an open circulation and the fact that these animals live in an environment that is more or less a microbial suspension, coagulation is important to avoid loss of hemolymph and to allow rapid capture of microorganisms into clots and at wound sites. The crustacean coagulation reaction is initiated by a transglutaminase from the hemocytes, which is released from the cells and causes a plasma-clotting protein to crosslink with each other. This plasma-clotting protein belongs to the vitellogenin superfamily of proteins.3 Apart from participating in immediate immune reactions such as clotting, melanization, phagocytosis, and encapsulation, hemocytes are important suppliers of different antimicrobial peptides, lectins, proteinase inhibitors, and opsonins such as the cell adhesion protein peroxinectin.4

Because of their large size and the substantial amount of blood (hemolymph) that can be collected, individual types of crustacean hemocytes can be separated and studied in detail. Three main types of hemocytes can be identified in most decapod crustaceans: hyaline cells, semigranular cells (SGCs), and granular cells (GCs); the main characteristics of these crustacean hemocyte types are summarized in Table 1.5-8

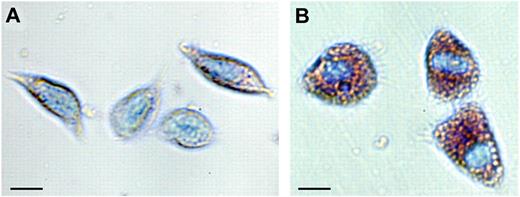

Hyaline cells are small and contain no granules, or very few, and may act as phagocytes. This cell type is rare in P leniusculus but more common in marine crustaceans,9 and so far, no molecular marker is available to identify this cell type. The number and proportion of different hemocyte types varies a great deal among crustaceans and is influenced by various environmental conditions.5 The SGC (Figure 1A)6 is usually the most abundant cell type, making up approximately 65% of the cells. This hemocyte type contains a variable number of small eosinophilic granules and is involved in early recognition, coagulation and, to some extent, phagocytizes. This is the main hemocyte type involved in encapsulation of microorganisms. Encapsulation reactions are usually followed by melanization, and the SGCs contain the components of the proPO system. The expression of one specific kazal-type proteinase inhibitor can be used as a marker for the differentiation of stem cells along the SGC lineage.

Blood cells (hemocytes, SGC, and GC) of the freshwater crayfish P leniusculus. Hemocytes were collected and separated according to Wu et al6 and stained with May-Grünvald eosin followed by Giemsa. (A) SGC, semigranular hemocytes; and (B) GC, granular hemocytes; bar = 10 μm.

Blood cells (hemocytes, SGC, and GC) of the freshwater crayfish P leniusculus. Hemocytes were collected and separated according to Wu et al6 and stained with May-Grünvald eosin followed by Giemsa. (A) SGC, semigranular hemocytes; and (B) GC, granular hemocytes; bar = 10 μm.

However, the main repositories for the proPO system are the GCs (Figure 1B), which are densely packed with large eosinophilic granules, and they release their contents by exocytosis on activation. Apart from the proPO system, the granules contain different antimicrobial peptides,7 various proteinase inhibitors,10 and the cell adhesion/degranulating factor peroxinectin, a homologue of vertebrate myeloperoxidase. The expression of myeloperoxidase mRNA is also an early sign of granulocyte differentiation in zebrafish.11 Superoxide dismutase is exclusively expressed by cells of the GC lineage and can be used to identify these cell types6 in crayfish (Table 1).

Crustacean HPT

Response to injury or infection leads to a dramatic loss of free circulating hemocytes, which is followed by a recovery accomplished mainly by rapid synthesis and release of new hemocytes from HPTs.5 The continuous formation of new hemocytes is essential for survival of an animal, and the process is tightly regulated in crayfish by factors released from circulating hemocytes.

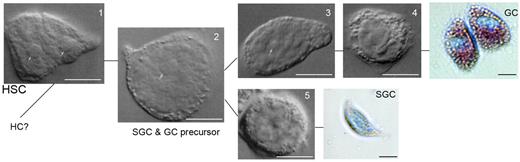

In decapod crustaceans, such as the shore crab Carcinus maenas, the lobster Homarus americanus, and the crayfish P leniusculus, HPT is composed of a series of ovoid lobules that collectively form a thin sheet on the dorsal part of foregut (Figure 2).12-14 Each lobule is surrounded by connective tissue and contains stem cells, prohemocytes, and more loosely associated mature hemocytes (Figure 2). Crayfish HPT encompasses at least 5 different cell types corresponding to the developmental stages of GCs and SGCs (Figure 3). Type 1 cells have a large nuclei surrounded by a small amount of cytoplasm, and these cells may be the precursor stem cells for the different cell lineages. Type 2 cells have large nuclei but larger cytoplasm-containing granules and may lead to SGCs and GCs. Type 1 and 2 cells are the main proliferating cells in the HPT, whereas the other cell types in the HPT can be categorized into precursors of GCs (types 3 and 4) or as a precursor of SGCs (type 5; Figure 3).

The HPT of the freshwater crayfish. (A) Localization of the HPT in crayfish underneath the carapace (the tissue covering the dorsal surface of the stomach and surrounded by a thin sheet of connective tissue). (B) The HPT can be isolated in one piece. Note the ophthalmic artery (AO, arrows) traversing the tissue in the anterior-posterior direction, bar = 2 mm. (C) A lobule of the HPT with a sharp apical end and diffuse distal region, bar = 20 μm. (D) BrdU incorporated into the HPT cells in vivo showing a high proliferation rate in the thin sheet of HPT cells (arrow on left) covering the stomach (arrow on right), bar = 100 μm.

The HPT of the freshwater crayfish. (A) Localization of the HPT in crayfish underneath the carapace (the tissue covering the dorsal surface of the stomach and surrounded by a thin sheet of connective tissue). (B) The HPT can be isolated in one piece. Note the ophthalmic artery (AO, arrows) traversing the tissue in the anterior-posterior direction, bar = 2 mm. (C) A lobule of the HPT with a sharp apical end and diffuse distal region, bar = 20 μm. (D) BrdU incorporated into the HPT cells in vivo showing a high proliferation rate in the thin sheet of HPT cells (arrow on left) covering the stomach (arrow on right), bar = 100 μm.

Five types of HPT cells in the HPT tissue and the 2 main lineages of HPT cells. Type 1 (HSC) and type 2 cells are the main proliferating cells in the HPT, whereas the other cell types in HPT can be categorized into precursors of GCs (types 3 and 4) or as precursor of SGCs (type 5), bar = 10 μm.

Five types of HPT cells in the HPT tissue and the 2 main lineages of HPT cells. Type 1 (HSC) and type 2 cells are the main proliferating cells in the HPT, whereas the other cell types in HPT can be categorized into precursors of GCs (types 3 and 4) or as precursor of SGCs (type 5), bar = 10 μm.

The HPT of crayfish is penetrated by vessels and provides a site for stem cell renewal as well as for the development of mature hemocytes that are released into the circulation as a rapid response to peripheral needs.5 After dissection from crayfish, the HPT can be easily cultured as a tissue, and the development of hemocytes migrating from the lobules can be studied. The primary culture of HPT cells enable the study of how crustacean hematopoiesis is regulated, and the method has been further developed by an efficient technique for RNAi using Histone 2A for transfection.15

Regulation of crustacean hematopoiesis

Transcriptional regulation

The formation and development of mature hemocytes involves proliferation, commitment, and differentiation from undifferentiated HPT cells. The transcriptional regulation of crustacean hematopoiesis has not been elucidated in detail. However, the facts that a GATA factor is critical for hemocyte and HPT cell survival,8 and that the Runx protein is important for specification of HPT cells into the SGC or GC lineage, imply that there is a conserved regulatory mechanism across taxonomic groups.16-18 Detailed studies of hematopoietic transcription factors and signaling pathways associated with Drosophila hematopoiesis have been comprehensively reviewed.16,17,19 Of special interest are the Runx protein homologues in crustaceans and Drosophila, which are closely associated with the differentiation of cells that express the proPO gene.16-18 In crayfish, Runx expression is a prerequisite for the final differentiation of SGCs and GCs. The Drosophila Runx homologue Lozenge (Lz) is needed for the development of the proPO-expressing crystal cell.17 Moreover, Ferjoux et al20 showed that the simultaneous binding of the GATA factor Srp, together with Lz to the promoter region of proPO, plays a critical role for expression of proPO in at least 16 different insect species. Srp/Lz-mediated gene activation via this module seems to play a central role in crystal cell differentiation by directing the coordinated expression of several genes in this lineage.20

In Drosophila, the crystal cells comprise a minor part of the hemocyte population in which the majority of cells are phagocytes, the so-called plasmatocytes. The plasmatocytes in Drosophila are specified by 2 glial cell missing (Gcm and Gcm2) transcription factors, and these cells are further developed into pupal macrophages after exposure to the moulting hormone ecdysone.7 In crustaceans, gcm factors have yet to be detected, indicating that cell types corresponding to the plasmatocytes are not present in these animals.

Humoral regulation

Although transcriptional regulation of hematopoietic cell development in invertebrates, such as insects and crustaceans, and vertebrates uses common elements, less conservation is evident in the humoral factors regulating hematopoiesis.7 Homologues of few hematopoietic cytokines have been found in invertebrate genomes.

Little is known about the events that regulate invertebrate hematopoiesis during development or infection, and studies about these processes are limited mainly to crustaceans and Drosophila. In crustaceans, hemocytes do not divide in the circulatory system; thus, new hemocytes need to be continuously and proportionally produced throughout the animal's lifetime. Experiments performed in the late 1800s revealed an increase in the mitotic index in the HPT after experimental bleeding,21,22 and since then, several investigators have confirmed that cell proliferation in the HPT can be influenced by different stress factors such as moulting,21,22 lipopolysaccharide injection,23 and manganese exposure.24 In addition, the number of blood cells can be experimentally decreased by injection of microbial polysaccharides, thus stimulating the rapid production and release of new cells from the HPT.5 New hemocytes are synthesized and partly differentiated in the HPT, but the final differentiation into fully functional hemocytes expressing proPO is not completed until the hemocytes are released into the circulation.5 Studies of isolated HPT cells from P leniusculus led to the isolation and characterization of a new group of cytokines, named astakines, from crayfish plasma. Two different astakines (Ast1 and Ast2, respectively) have been detected in crustaceans.

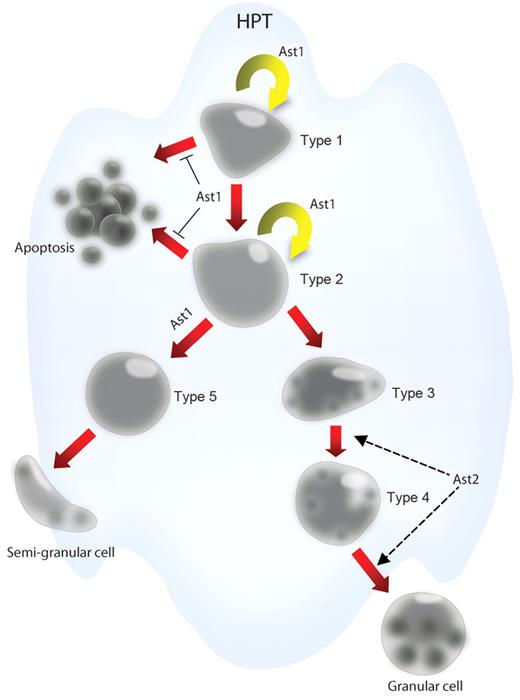

Astakines contain a conserved domain with 10 cysteines with conserved spacing, which is homologous to the structure of vertebrate PROKs. The crustacean astakines are produced by hemocytes and are released into the plasma. Ast1 and 2 are found in crayfish, and Ast2 shows high a similarity with shrimp and other arthropod astakines.25 A GenBank search reveals the presence of astakines in several crustaceans, scorpions, spiders, ticks, as well as in hemipteran, hymenopteran, and blattodean insects. Surprisingly, these small peptides are not found in dipterans such as Drosophila or Anopheles.25 However, the molecular role of astakines has only been studied in detail in P leniusculus (a summary of astakine effects is shown in Figure 4). Ast1 was originally purified from plasma and was identified by its ability to induce proliferation of HPT cells in vitro. Ast1 was subsequently cloned from crayfish hemocyte cDNA. It encodes 104 amino acid residues with a signal peptide and a PROK domain.26 This cytokine is most abundant in and mainly secreted from SGCs. Increased plasma levels of Ast1 are found shortly after challenging animals with microbial polysaccharides and before the recruitment of hemocytes from the HPT. In vivo and in vitro experiments show that recombinant Ast1 stimulates the proliferation of HPT cells and induces differentiation of the SGC lineage. In Ast1-silenced animals, the ability to recruit new hemocytes after lipopolysaccharide challenge is completely abolished.26 In contrast, Ast2 does not induce proliferation of HPT cells in vitro but increases the number of mature GCs by an unknown pathway.25

The effects of astakine on hematopoietic processes in crayfish. Ast1 promotes the proliferation of HPT cells and blocks apoptosis of these cells. Further ast1 promotes the differentiation of HPT cells along the SGC lineage. Ast2 plays an important role in the maturation of the GC lineage.

The effects of astakine on hematopoietic processes in crayfish. Ast1 promotes the proliferation of HPT cells and blocks apoptosis of these cells. Further ast1 promotes the differentiation of HPT cells along the SGC lineage. Ast2 plays an important role in the maturation of the GC lineage.

In crustaceans, the astakines are currently the only known molecules that act as hematopoietic growth factors. In Drosophila, 3 PDGF/VEGF-related factors (PVFs) are present, and the PVFs and their receptor (PVR) play an important role in the survival of hemocytes in the Drosophila embryo. Only PVF2 can promote proliferation of larval hemocytes.27 However, it is not clear whether PVF2 acts as a chemotactic agent for plasmatocytes or as a direct stimulus of mitosis and differentiation. Interestingly, no PVF homologue has been identified in crustaceans, providing another example of divergence among animal species in humoral hematopoietic regulation.

Ast1 decreases extracellular transglutaminase activity

The presence of “stem cell niches” was proposed by Schofield28 as a hypothesis to describe the physiologically limited microenvironment that supports stem cells.28,29 The first experimental evidence for the presence of such a niche came from studies of the ovary in Drosophila, where the “germarial tip” adjacent to the germline stem cells was defined as the niche supporting stem cells in the Drosophila ovary,30 whereas the hub, located at the tip of Drosophila testis, served this function in the testis.29,30 Later, osteoblasts primarily lining the trabecular bone surface were identified as the key component of the hematopoietic stem cell HSC niche in mammals.31 In Drosophila, the posterior signaling center was identified as a hematopoietic niche in the primary lobe of the lymph gland.32-34 In crustaceans, such a niche in the HPT has not been found, although stem cells exclusively occupy the apical parts of the hematopoietic lobules and are closely attached together to the extracellular matrix (ECM) envelope of the lobules. The endothelial cells, capsular cells, and stromal cells, together with the ECM in Sicyonia ingentis (shrimp) hematopoietic nodules, may provide a niche-like microenvironment for the stem cells in this species.12

Collagen is a major component of the HPT of crustaceans, and in crayfish HPT tissue, both type I and type IV collagens are present.14 Thus, a mixture of type I collagenase and type IV collagenase are used to dissociate HPT cells from HPT.5,26 Collagens are also well-known substrates for transglutaminase.35,36 In crayfish, collagen IV is a potential substrate of surface transglutaminase of HPT cells, and recent findings reveal the importance of collagen I as a matrix protein for the development of SGC (our unpublished results). Surface transglutaminase may play an important role in regulating the interaction between HPT cells and the ECM.

Transglutaminase is an abundant protein in the HPT cells of crustaceans, and an important role for this enzyme in hematopoiesis was recently shown.8 In cultured HPTs, high transglutaminase activity is detected in cells in the center of the tissue, whereas cells migrating from this tissue have low or no transglutaminase activity. Transglutaminase is important for keeping HPT cells in an undifferentiated stage inside the HPT, and if transglutaminase mRNA expression is inhibited, the cells start to differentiate and migrate out from the tissue.8 A decrease in the activity of extracellular transglutaminase occurs after the addition of Ast1 to HPT cells. However, the transcription of transglutaminase mRNA in HPT cells is not affected by the addition of Ast1, suggesting that regulation of extracellular transglutaminase activity by Ast1 is achieved at a later stage. The finding of high transglutaminase activity in HPT cells and knowing that transglutaminase activity can be indirectly blocked by the treatment of Ast1 clearly shows an important role for transglutaminase in hematopoiesis. Transglutaminase activity is most likely involved in the crosslinking of ECM proteins, allowing for the creation of a specific niche-like microenvironment for stem cells.

Ast1 as a hematopoietic growth factor

The HPT in P leniusculus rapidly proliferates (Figure 2D), and cell homeostasis is achieved by continuous proliferation and apoptosis of the stem cells. After challenge with microbial polysaccharides, recruitment of hemocytes from the tissue is initiated, and the rate of apoptosis decreases, indicating that more cells are directed along differentiation pathways instead of undergoing apoptosis.5 When HPT stem cells are cultured without Ast1, these cytokine-deprived cell cultures die by apoptosis. Consequently, Ast1 is an important regulator at the crossroad between proliferation/differentiation and apoptosis. Recently, a new protein that is responsible for preventing apoptosis in the HPT cells was detected.37 This protein, named crustacean hematopoietic factor (CHF), is a novel protein with similarity to the N-terminal region of the human cysteine rich transmembrane bone morphogenetic protein regulator 1 (chordin-like), also known as CRIM1. Silencing of CHF by RNAi in live animals and in vitro HPT cultured cells reveals a role for CHF in preventing cell apoptosis. Ast1 is necessary for the transcription of CHF in stem cells because culturing HPT cells without the supplementation of Ast1 results in a continuous decrease of CHF transcription. CHF transcription in HPT cells can also be induced after treatment with Ast1.37

Crustacean hematopoiesis is rhythmically controlled

The hematopoietic process of crayfish is under circadian control, and Ast1 is one mediator of this rhythm.38 Ast1 is highly expressed in the early morning after a dark period, and expression gradually decreases during exposure to light. Recent genetic and physiologic evidence has shown that vertebrate PROKs are transmitters of circadian rhythms of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain of mammals.39,40 Circadian rhythm is regulated by a highly conserved set of regulatory proteins, and stem cell activities may be modulated by such regulatory proteins. Oscillations in proliferative activity and recruitment of hematopoietic progenitor cells have been demonstrated in mammals.41,42 Although vertebrate PROKs have been assigned a role as an suprachiasmatic nucleus output molecule, no role in regulating rhythmic oscillations in hematopoiesis has been proposed, and the expression pattern of Ast1 suggests an evolutionarily conserved function for PROK domain proteins in mediating circadian rhythms. Therefore, it should be of interest to see whether any PROK has such a role in vertebrate hematopoiesis.

Astakines and PROKs in hematopoiesis

Proteins belonging to the PDGF/VEGF family are important for early plasmatocyte spreading in Drosophila embryos.43 However, similar proteins do not seem to be present in crustaceans. Instead, the astakines are important hematopoietic growth factors in crustaceans, and they are found in several different insect orders, with the exception of diptera (such as Drosophila), coleopteran, and Lepidoptera. These results indicate the complexity of the evolution of blood cells, and studies in which the authors use only one species may not fully reveal this complexity.

Astakines are homologues of vertebrate PROKs, a family of small secreted proteins of approximately 80 amino acids that were initially isolated from the venom of the black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, in 1980 as nontoxic mamba intestinal toxin 1 (MIT1)44 and later the Bv8 (Bombina variegata protein with a molecular mass of 8 kDa) peptide from skin secretions of the frog Bombina variegata.45 Since then, 2 homologues of MIT1 and Bv8 have been identified in different mammals and were named PROKs because of their ability to induce gastrointestinal smooth muscle contraction. All vertebrate PROKs share a conserved N-terminal amino acid motif, AVIT, and contain a PROK domain in their C-terminus.46-48 The latter domain is similar in structure to that of colipase and the C-terminal part of Dickkopf (Dkk) proteins. PROK1 and 2 are encoded by 2 different genes and can be distinguished by their signal peptide; there is a poly-L present in the signal peptide region in PROK2.49 Moreover, PROK2 has an alternatively spliced form with an insert of 20 or 21 amino acids after residue 47.46 PROK2 is encoded by 4 exons, and exon 3 is subjected to alternative splicing.50 Interestingly, exon 2 and exon 4 of the PROK2 gene encode a protein of high similarity to Ast1, whereas exon 1 encodes the 4 N-terminal (AVIT) amino acids that are not found in any invertebrate astakine.

All vertebrate PROK1s and PROK2s have been experimentally shown to induce gastrointestinal smooth muscle contraction.44,45,47 Apart from functioning in intestinal muscle contractility, PROKs are thought to have roles in neurogenesis, pain perception, food uptake, appetite regulation, and regulation of circadian clocks.51 These different biologic roles of vertebrate PROKs have been extensively reviewed.52-54 More interestingly, from an immunologic point of view, PROKs are differentially expressed within immune cells and play roles in vertebrate hematopoiesis in addition to acting as potent agents to induce angiogenesis and proinflammatory immune responses.55-57 PROK1 induces differentiation of murine and human BM cells into the monocyte/macrophage lineage,51,58 whereas PROK2 has similar effects on monocyte lineage. PROK2 also promotes granulocytic differentiation of cultured human and mouse hematopoietic stem cells (Table 2).25,37,51,58-63 The structural and functional similarities between astakines and the vertebrate PROKs point to an ancient role for these proteins as cytokines.

The functions of vertebrate PROKs are mediated through their interaction with receptors on the target cell surface.51,64 2 closely related G-protein–coupled receptors have been identified and named as PROKR1 and PROKR2.60-62 These receptors belong to the family of neuropeptide Y receptors, and they are encoded by 2 different genes. Vertebrate PROKRs are coupled to Gq, Gs, and Gi, which may lead to various signaling pathways inside the cells. Calcium mobilization, activation of Akt kinase and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and phosphoinositol turnover all result from PROKR activation.65 Similarly, Ast1 acts via activation of MAPK and Akt kinase (X.L. and I.S., unpublished results, September 20, 2010). The conserved first 4 N-terminal amino acids (AVIT) in all vertebrate PROKs are critical for their interaction with the PROKRs, and any disruption of this hexapeptide sequence will result in loss of activity of the vertebrate PROKs.51,66 Ten cysteines with identical spacing in the C-terminal domain are also important for PROKs to keep their 3-dimensional structure, and mutating a single cysteine can disrupt the biologic activity of PROKs.

The putative structure of Ast1 shows that it has 4 cysteine bridges, whereas MIT1, Dkk, and colipase are stabilized by 5 cysteine bridges. Both Ast1 and Ast2 are more negatively charged than MIT1 and Dkk, and there is also a large charge difference at the N-terminus between Ast1 and Ast2.25 These data may explain the difference in receptor binding between vertebrate PROKs and crustacean astakines.

The main difference between invertebrate astakines and their vertebrate prokineticin homologues is that all invertebrate astakines lack the AVIT motif in their N-terminal domain, which is present in all members of the vertebrate prokineticin family. Therefore, Ast1 and its invertebrate homologues may use another molecule as a receptor. A Bv8 homologue protein, ACTX-Hvf17, was isolated from the venom of the Blue Mountains funnel-web spider, Hadronyche versuta, which shares 32% amino acid identity with Bv8, including the 10 conserved cysteine residues. Interestingly, ACTX-HVf17 was unable to stimulate vertebrate gastrointestinal smooth muscle contractility, and accordingly, this molecule failed to bind to the prokineticin receptors PROKR1 and PROKR2.67 In P leniusculus, HPT Ast1 and Ast2 bind to different cell types, and the receptor for Ast2 has yet to be identified. However, it is clear that this cytokine binds to a different set of cells than Ast1. A covalent crosslinking technique, by which recombinant Ast1 was linked to the surface of HPT cells, revealed an ATP synthase β-subunit on the surface of some HPT cells as the receptor for crayfish Ast1. PROK1 did not bind to this receptor, demonstrating that vertebrate PKs and invertebrate astakines have different receptor binding capabilities.63

ATP synthase is a well-known mitochondrial enzyme complex, but several recent observations suggest that this enzyme is also located on the cell surface.68,69 The complex consists of a F0 portion and a F1 portion. The F0 portion is a proton channel embedded in the membrane. The F1 portion is composed of 3 α-subunits and 3 β-subunits together with one γ-subunit, one δ-subunit, and one ϵ-subunit.68 The main function of the enzyme complex is synthesis or hydrolysis of ATP, and this enzyme is present in the mitochondria and chloroplast, as well as in the plasma membrane of some bacteria.69 The function of ATP synthase in the membrane of these bacteria is to participate in the regulation of pH. Recent studies show that this enzyme complex is located on the plasma membrane of some eukaryotic cells, with its F1 portion exposed to the extracellular space,69 and is expressed by endothelial cells,70,71 hepatocytes,72 adipocytes,73 keratinocytes,74 and several type of human cancer cells.69 The ATP synthase enzyme complex was first detected on the cell surface of cancer cells in 1994.75 Later, when Moser et al70 were trying to find a receptor for angiostatin, ATP synthase was identified as a receptor for angiostatin on the surface of endothelial cells.70,76 The function of ATP synthase on the cell surface is not fully understood, but the enzyme is frequently found on the surface of highly proliferative cells and various cancer cell lines.69

Crayfish HPT cells proliferate at a high rate; thus, the finding of surface ATP synthase as a receptor reveals an evolutionary conserved mechanism for receptor interaction on highly proliferating cells. Whether astakine regulation of crayfish hematopoiesis is mediated by further activation of a G-protein–coupled receptors via changes in local ADP/ATP concentrations awaits further investigations.

Conclusion

Invertebrates provide a simple system to study hematopoiesis. However, the molecular mechanism of this dynamic process in invertebrate animals is still not fully understood. Most of the current knowledge regarding the regulation of invertebrate hematopoiesis is derived from studies on Drosophila. These studies imply that several transcription factors and signal transduction pathways involved in this process are highly conserved between Drosophila and mammals. However, hematopoiesis is also regulated by humoral factors, such as numerous cytokines in vertebrates, but this regulation is not fully understood in invertebrates, and the evolution of these factors seems to be far more complex.7

The recent discovery in crustaceans of astakines that contain the prokineticin domain provides an opportunity to explore an unknown field. The astakines are the first invertebrate cytokines to qualify as hematopoietic growth factors, which can stimulate the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of HPT cells. The astakines and their vertebrate homologues, PROKs, share similar functions in hematopoiesis, but the underlying mechanisms involved in their regulation are currently unknown.

In conclusion, studies of astakine-induced hematopoiesis in crustaceans will further our understanding of the regulation of invertebrate hematopoiesis and broaden our view about how hematopoiesis is diversely regulated in different invertebrate species. These studies may advance the knowledge about the evolution of different blood cell lineages and give new perspectives into the multifaceted processes of innate immunity.

Authorship

Contribution: X.L. and I.S. contributed equally to the writing of this review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Irene Söderhäll, Department of Comparative Physiology, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18A SE75236 Uppsala, Sweden; e-mail: Irene.Soderhall@ebc.uu.se.