Clinicians typically assume that steroid-refractory acute GVHD can be overcome only by increasing the intensity of immunosuppressive treatment, but in this issue of Blood Luft et al suggest that more effective approaches might emerge from an unexpected direction.1

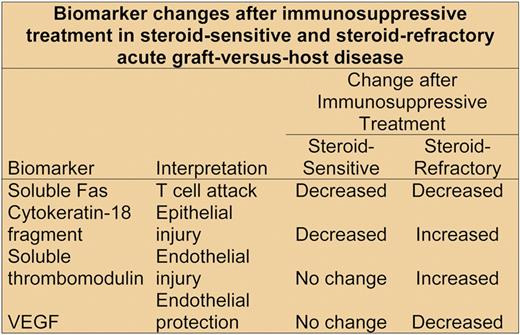

Biomarker changes after immunosuppressive treatment in steroid-sensitive and steroid-refractory acute GVHD.

Biomarker changes after immunosuppressive treatment in steroid-sensitive and steroid-refractory acute GVHD.

Steroid-refractory acute GVHD poses one of the most vexing clinical problems faced by physicians involved in hematopoietic cell transplantation. We have very little information regarding the pathogenesis of this problem, and clinical experience indicates that intensified immunosuppression does not usually provide an effective remedy.2 In a recent case at our center, for example, a patient was treated sequentially with infliximab, mycophenolate mofetil, extracorporeal photopheresis, sirolimus, and both equine and rabbit antithymocyte globulin in rapid succession within a period of 8 weeks, all to no avail.

Luft and colleagues now offer a novel perspective and some thought-provoking ideas regarding the pathogenesis of steroid-refractory GVHD. They analyzed biomarkers indicating T-cell attack, epithelial injury, and endothelial injury in serum samples collected serially from 23 patients with steroid-sensitive acute GVHD and 25 patients with steroid-refractory GVHD, using the initial immunosuppressive treatment of GVHD as the time anchor (see figure). The concentration of biomarkers indicating T-cell attack, including soluble Fas ligand, among others, decreased in both groups after treatment was started. Epithelial injury measured according to the concentration of cytokeratin-18 fragments3 decreased after immunosuppressive treatment in the steroid-sensitive group but increased in the steroid-refractory group. Endothelial injury measured according to the concentration of soluble thrombomodulin-1 also increased after immunosuppressive treatment in the steroid-refractory group but not in the steroid-sensitive group.

Taken together, these observations support previous results indicating that GVHD involves an attack on endothelial cells as well as epithelial cells,4,5 but earlier studies could not explain how endothelial injury emerges while T-cell attack is subsiding during immunosuppressive treatment. Luft and colleagues showed that the steroid-responsive and steroid-refractory groups differed in 2 key ways. First, concentrations of angiopoietin-2 (ANG2) were higher in the steroid-refractory group before transplantation, at the beginning of immunosuppressive treatment, and during subsequent follow-up. ANG2 makes endothelial cells more sensitive to inflammatory cytokines produced by alloactivated donor T cells.6 These cytokines cause endothelial cells to lose expression of thrombomodulin, a molecule that protects cells by catalyzing activation of protein C and by inhibiting apoptosis.7 Endothelial cells with reduced expression of thrombomodulin are therefore more vulnerable to damage after stress. The second key observation is that vascular endothelial-derived growth factor (VEGF) concentrations decreased after immunosuppressive treatment in the steroid-refractory group but not in the steroid-sensitive group. VEGF inhibits ANG2, and in the absence of VEGF, ANG2 causes endothelial cell death.8

At first glance, it might seem plausible that the increased concentrations of thrombomodulin-1 and ANG2 in the serum represent results of steroid-refractory GVHD, and not the cause. As noted by Luft et al, however, the observation that ANG2 concentrations were higher in the steroid-refractory group even before transplantation supports their hypothesis that baseline endothelial vulnerability has a causal role in the pathogenesis of steroid-refractory acute GVHD. If correct, this hypothesis would imply that efforts to control steroid refractory GVHD by increasing the intensity of immunosuppressive treatment are aimed at the wrong target.

As always, unanswered questions remain, and more work in this new and potentially exciting direction is needed. What causes the increased ANG2 concentration at baseline in patients at risk of steroid-refractory GVHD? How is endothelial injury linked to continued epithelial injury in the absence of sustained attack by T cells in patients with steroid-refractory GVHD? What causes VEGF concentrations to decrease during immunosuppressive treatment in patients with steroid-refractory GVHD? What other factors influence the vulnerability of endothelial cells to injury after hematopoietic cell transplantation? The novel observations by Luft and colleagues, together with eagerly awaited answers to these questions, provide hope that insights from vascular biology might yield long-awaited improvements in treatment for steroid-refractory GVHD.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■