Abstract

Oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many human diseases including Fanconi anemia (FA), a genetic disorder associated with BM failure and cancer. Here we show that major antioxidant defense genes are down-regulated in FA patients, and that gene down-regulation is selectively associated with increased oxidative DNA damage in the promoters of the antioxidant defense genes. Assessment of promoter activity and DNA damage repair kinetics shows that increased initial damage, rather than a reduced repair rate, contributes to the augmented oxidative DNA damage. Mechanistically, FA proteins act in concert with the chromatin-remodeling factor BRG1 to protect the promoters of antioxidant defense genes from oxidative damage. Specifically, BRG1 binds to the promoters of the antioxidant defense genes at steady state. On challenge with oxidative stress, FA proteins are recruited to promoter DNA, which correlates with significant increase in the binding of BRG1 within promoter regions. In addition, oxidative stress-induced FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of a FA-BRG1–promoter complex. Taken together, these data identify a role for the FA pathway in cellular antioxidant defense.

Introduction

Oxidative DNA damage is a major source of genomic instability. The most prevalent lesion generated by intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) is 8-hydroxydeoxy guanosine (8-oxodG). This lesion causes G:C to T:A transversion mutations and is considered highly mutagenic.1 There is compelling evidence that 8-oxodG levels are elevated in various human cancers.2,3 and in animal models of tumors.4,5 ROS-induced DNA damage can also result in single- or double-strand breaks, which are lethal to the cell if not repaired.6,7 Although there is a great deal known about DNA repair, we have a limited understanding of the involvement of specific repair pathways in protecting cellular DNA from oxidative damaging agents, particularly ROS. The major pathways involved in DNA repair include repair of single-base damage by the base excision repair (BER) pathway, repair of lesions that distort the DNA helix by the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway, and repair of DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination (HR) and nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathways.8-10 Although the specificity and efficiency of each of these DNA repair pathways is critical to ensure genome stability, the complexity of ROS-induced oxidative DNA damage may require coordination between these different pathways.

Cells have developed a battery of defense mechanisms to protect against damage induced by oxidative stress. Antioxidant defense enzymes, including superoxide dismutases, catalase, glutathione peroxidases and peroxiredoxins, as well as nonenzymatic scavengers such as glutathione and carotenoids can directly eliminate ROS.11 Other cellular enzymes can repair DNA damage induced by ROS.12 Moreover, ROS can influence the selective activation of oxidative stress-responsive transcription factors. Indeed, the first line of defense against oxidative damage is the induction of stress-response genes, many of which encode antioxidant defense enzymes.13 For example, one of the best-studied transcription factors activated by oxidative stress is the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which is responsible for the induced expression of several antioxidant defense genes.14 Promoter recognition is mediated through transcription factors. For most transcription factors, consensus binding sites in promoter regions are moderately to heavily guanine-cytosine rich (GC-rich) thereby making them highly susceptible to ROS-induced 8-oxodG formation.1 Fanconi anemia (FA) is a genomic instability syndrome that is defective for a DNA-damage response pathway which is essential for defense against a variety of cellular stresses including oxidative stress.15 Inactivation of this pathway, as seen in FA patients, results in hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and cancer susceptibility.16-18 FA is genetically heterogeneous, with 15 complementation groups (A-P) identified thus far.19 Eight of the 15 FA proteins form a nuclear complex that is responsible for stress-induced monoubiquitination of FANCD2 and FANCI. Other FA proteins—including FANCD1 (which is the breast cancer protein BRCA2), FANCJ, FANCN, and FANCO, as well as BRCA1—are also recruited to nuclear foci that contain damaged DNA and which consequently influence important cellular processes such as DNA replication, cell-cycle control, and DNA damage repair.16-18 It is now recognized that FA is a unique disease model characterized by abnormal accumulation of ROS and a dysfunctional response to oxidative stress.15,20 In the present study, we show that major antioxidant defense genes are down-regulated in BM cells of FA patients and that this down-regulation is selectively associated with increased oxidative DNA damage in the promoters of these antioxidant defense genes. Furthermore, we identify a role for FA proteins in protecting these major antioxidant defense genes from oxidative damage.

Methods

Analysis of DNA damage

Genomic DNA from H2O2 treated or untreated cells was isolated under conditions that prevent in vitro oxidation, including the presence of 50μM of the free radical spin trap pheny-butyl nitrone (PBN; Sigma-Aldrich), nitrogenation of all buffers, and avoidance of phenol and high temperature. DNA damage was assayed by cleavage of genomic DNA with formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (Fpg; New England Biolabs),21 which acts as an N-glycosylase and AP-lysase to excise 8-oxoguanine and other damaged bases, and which creates a single-strand break that prevents PCR amplification. Quantitative RT-PCR was then used to determine the content of specific intact sequences (see supplemental data for list of primer sequences, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA was used to determine the percentage of intact DNA. Incorporation of 8-oxo-dG was assayed by chromatin immunoprecipitation with a mAb to 8-oxo-dG.22

Host cell reactivation assay

The host cell reactivation assay of DNA repair used the pSGG-promoter reporter system (SwitchGear), into which 1-3 kb human promoter fragments of 4 antioxidant defense genes (GCLC, GPX1, GSTP1, and TXNRD1) and 2 housekeeping genes (GAPDH and β-Tubulin) were cloned. Luciferase reporter plasmids were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 1 hour in vitro, then transfected into FA-A or correct fibroblasts. Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were lysed and analyzed by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega). To control for transfection efficiency, luciferase activity of the promoter was normalized to the activity of Renilla luciferase. The luciferase activity of H2O2-damaged reporters was expressed relative to the activity of the corresponding nondamaged reporter. To assess DNA damage in the promoter regions of the transfected reporters, the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based assay was used with PCR primers against regions of the pSGG plasmid that encompassed the cloned promoter to exclude amplification of endogenous promoter sequences of the target genes.

Genetic reconstitution of FA-A and FA-D2 cells

Retroviral vectors encoding human pMMP-Puro, pMMP-wt-FANCD2, and pMMP- FANCD2-K561R were provided by Dr Alan D'Andrea (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Retroviral vectors MIEG3, MIEG3-FANCA, and MIEG3-FANCC have been described elsewhere.23 Retroviruses were prepared by the Vector Core of Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH). Retroviral supernatant was collected at 36, 48, and 72 hours, respectively, after transfection. For retroviral transduction, cells were seeded on fibronectin (8 μg/cm2; Takara) coated plates preloaded with viral supernatants and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 4 hours. An equal volume of medium was then added to the culture. Transductions were repeated 2 times.

Chromatin fractionation

Chromatin was isolated as described previously.24 Briefly, treated or untreated cells were harvested and washed with cold PBS then collected by centrifugation. Pellets were suspended in cold buffer A24 and incubated at room temperature for 2 minutes to permeabilize the cells. Pellets were again collected by centrifugation and washed with cold buffer A. Nuclei were then digested with RNase-free DNase I (200 U/mL; Roche) in buffer A for 30 minutes. Pellets were extracted with cold buffer A containing 250mM ammonium sulfate for 5 minutes. The supernatant (chromatin fraction) was collected by centrifugation at 956g for 3 minutes. Cell-equivalent volumes of the chromatin extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated Abs.

ChIP

The ChIP assay was performed as described previously21 with minor modifications. Briefly, chromatin was cross-linked by adding 37% formaldehyde with rotation at 4°C for 10 minutes and then room temperature for 20 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10mM EDTA, 50mM Tris-HCL, pH 8.1, and protease inhibitors) and sonicated with repeated 10-second pulses. Residual unfragmented chromatin was removed by centrifugation at 15 000g for 10 minutes. The amount of DNA in the supernatant was quantified and adjusted to 100 ng/μL. Supernatant (200 μL) was diluted 10-fold in 2 mL of ChIP dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2mM EDTA, 16.7mM Tris-HCL, pH 8.1, 167mM NaCl, and protease inhibitors), and precleared twice with BSA-blocked protein L agarose (Pierce). The beads were centrifuged and the supernatant was divided into 500-μL aliquots representing input DNA, and material for immunoprecipitation, and an IgG control. Primary Ab was added and incubated at 4°C overnight. Anti–8-oxoguanine (Chemicon), FANCD2 (Novus Biologicals), BRG1 (Millipore), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), acetylated H3K9/14 (Millipore), and methylated H3K9 (Millipore) Abs were used for immunoprecipitation, and ChromPure rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was used for the IgG control.

Results

The FA pathway engages in the oxidative stress response

To examine whether the FA pathway is involved in the oxidative stress response, we subjected primary BM progenitor cells from FA-A and FA-C patients to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a potent producer of ROS. We observed decreased colony formation in FA BM samples compared with normal BM samples, and a significantly greater decrement in colony formation after H2O2 treatment in the cells derived from FA patients (Figure 1A). To further define the involvement of FA proteins in the oxidative stress response, we also challenged lymphoblasts derived from FA-A or FA-C patients with increasing doses of H2O2. Again, both FA-A and FA-C cells showed a dose-dependent decrease in survival (Figure 1B). Reconstitution of the mutant cells with the FANCA or FANCC gene prevented H2O2-induced killing (Figure 1B). Because DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest is a hallmark of FA cells,25 we asked whether oxidative stress induced accumulation of FA cells in the G2/M phase. Indeed, H2O2 treatment led to a significantly increased G2/M population in FA-A or FA-C lymphoblasts compared with normal cells (supplemental Figure 1A). To biochemically demonstrate the activation of the FA pathway in the oxidative stress response, we examined FANCD2 monoubiquitination, a critical step in the regulation of DNA repair by the FA pathway.26 H2O2 induced FANCD2 monoubiquitination (supplemental Figure 1B) as well as FANCD2 foci formation (supplemental Figure 1C) in genetically corrected, but not mutant, FA-A or FA-C cells. Together, these results indicate that the FA pathway is engaged in the oxidative stress response.

Down-regulation of antioxidant genes in FA BM cells. (A) Hypersensitivity of FA BM progenitors to H2O2. BM cells from 5 FA-A and 2 FA-C patients, as well as 5 healthy donors, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by a colony-forming assay. Colony numbers were counted 10 days after plating. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B) Hypersensitivity of FA LCLs to H2O2. FA-A LCLs and cells corrected with the FANCA gene were treated with increasing doses of H2O2 for 2 hours followed by culture in fresh medium for an additional 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed for cell survival. (C) BM cells from 5 FA-A, 1 FA-B, 2 FA-C, 1 FA-D1, 1 FA-I, and 1 FA-J patients and healthy donors were used for pathway-specific (oxidative stress and antioxidant defense) array analysis. Eighty-four genes involved in antioxidative stress response were analyzed. The data represent the fold down-regulation of the indicated genes in FA samples relative to healthy donors. Fold down-regulation = −1/(fold difference), where fold difference = [2−ΔΔCt (FA)]/[2−ΔΔCt (healthy)]. (D) RT-PCR analysis of antioxidant gene expression in FA-A BM cells. RNA was extracted from BM cells from 2 FA-A patients and 2 healthy donors followed by RT-PCR analysis. (E) Western analysis of antioxidant gene products in FA-A BM cells. Protein lysates were prepared from cells described in panel B followed by Western blot analysis using the indicated Abs. Relative mRNA and protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The results were plotted after normalization with β-actin as an internal control.

Down-regulation of antioxidant genes in FA BM cells. (A) Hypersensitivity of FA BM progenitors to H2O2. BM cells from 5 FA-A and 2 FA-C patients, as well as 5 healthy donors, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by a colony-forming assay. Colony numbers were counted 10 days after plating. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B) Hypersensitivity of FA LCLs to H2O2. FA-A LCLs and cells corrected with the FANCA gene were treated with increasing doses of H2O2 for 2 hours followed by culture in fresh medium for an additional 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed for cell survival. (C) BM cells from 5 FA-A, 1 FA-B, 2 FA-C, 1 FA-D1, 1 FA-I, and 1 FA-J patients and healthy donors were used for pathway-specific (oxidative stress and antioxidant defense) array analysis. Eighty-four genes involved in antioxidative stress response were analyzed. The data represent the fold down-regulation of the indicated genes in FA samples relative to healthy donors. Fold down-regulation = −1/(fold difference), where fold difference = [2−ΔΔCt (FA)]/[2−ΔΔCt (healthy)]. (D) RT-PCR analysis of antioxidant gene expression in FA-A BM cells. RNA was extracted from BM cells from 2 FA-A patients and 2 healthy donors followed by RT-PCR analysis. (E) Western analysis of antioxidant gene products in FA-A BM cells. Protein lysates were prepared from cells described in panel B followed by Western blot analysis using the indicated Abs. Relative mRNA and protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The results were plotted after normalization with β-actin as an internal control.

Expression of antioxidant defense genes is down-regulated in FA cells

We hypothesized that the oxidant hypersensitivity of FA cells might have resulted from a compromised interaction between the FA pathway and other cellular oxidative stress-response pathways. To investigate whether FA proteins modulated genes involved in oxidative stress response, we first performed pathway-specific gene array analysis using BM samples from FA-A patients and healthy donors. We found that important genes functioning in antioxidant defense and ROS metabolism were significantly down-regulated in FA-A samples, compared with those of normal donors (supplemental Figure 2). Several major antioxidant defense genes, including glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), glutathione peroxidase 3 (GPX3), peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3), superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 (SOD1 and SOD2), thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1), NAD(P)H:quinone oxireductase (NQO1) and catalase (CAT), showed a > 20-fold down-regulation in FA patients, compared with healthy donors (Figure 1C). We confirmed these gene profile data using RT-PCR (Figure 1D) and Western blotting (Figure 1E) using BM cells from 2 pairs of FA-A patients and healthy donors. We also observed similar down-regulation of these antioxidant defense genes in BM samples from patients with mutations in the FANC -B, -C, -D1, -I, and -J genes, which correspond to the respective FA -B, -C, -D1, -I, and -J complementation groups (Figure 1C). These results suggest that the FA pathway engages the cellular oxidative response through regulation of antioxidant defense genes.

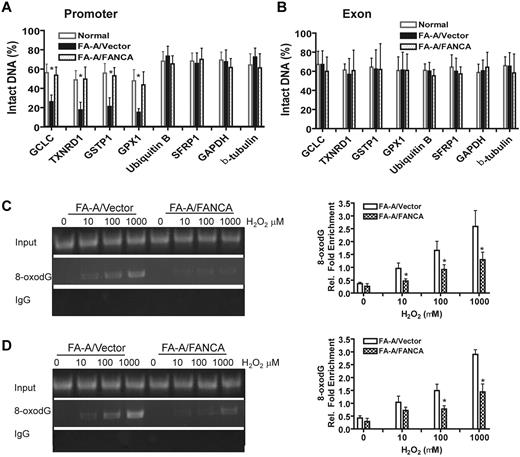

Down-regulation of antioxidant defense genes in FA cells is associated with a selective increase in promoter DNA damage

Because the down-regulation of the antioxidant defense genes in FA cells was identified at the transcriptional level, we asked whether there was increased oxidative damage in the promoter region of these genes. We treated FA-A and genetically corrected lymphoblasts with H2O2 and isolated genomic DNA to assay oxidative DNA-damage repair. This assay used Fpg,21 an N-glycosidase and AP-lyase that selectively cleaves oxidative-damaged bases predominantly 8-oxodG. Because Fpg creates a single strand break at a damaged base, rendering it resistant to PCR amplification, damage to a defined DNA region can be determined by a decrease in intact DNA for that specific sequence. For instance, there was a marked reduction of intact DNA after Fpg cleavage of the GPX1 gene promoter DNA in FA-A cells (supplemental Figure 3A). In contrast, the same promoter region of the GPX1 gene showed minimal DNA damage in the genetically corrected cells (supplemental Figure 3B). This index of DNA damage was compared for housekeeping genes (GAPDH, actin, and β-tubulin) that were stably expressed in both FA and normal cells (Figure 1D-E). DNA damage, indicated by a reduction in intact DNA, was markedly increased in the promoters of several antioxidant defense genes, including GCLC, TXNRD1, GSTP1 and GPX1, compared with their coding regions in FA-A lymphoblasts (Figure 2A-B). Normal cells or genetically corrected FA-A cells showed significantly less promoter DNA damage in the antioxidant genes (Figure 2A-B). To demonstrate that the increased levels of DNA damage in the promoters were specific to the antioxidative defense genes, we analyzed oxidative DNA damage to the promoters on 2 additional control genes, Ubiquitin B and SFRP1, which are not involved in the oxidative stress response.21 Notably, we did not observe a significant increase in DNA damage in the promoter regions of these genes in FA-A cells, compared with their genetically corrected counterparts (Figure 2A-B). Together, these results demonstrate that promoters of the antioxidant defense genes were selectively damaged by oxidative stress in FA cells.

Down-regulation of antioxidant genes is associated with a selective increase in promoter DNA damage in FA cells. (A) Increased promoter DNA damage in antioxidant genes in FA-A cells. FA-A cells transduced with empty vector or cDNA-encoding FANCA, as well as a normal control, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by 12 hours of culture in fresh medium. Genomic DNA was isolated followed by FPG cleavage and qPCR using primers specific for the promoters of the indicated genes. The percentage of intact DNA represents the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA. (B) DNA damage in the coding sequences of antioxidant defense genes. The same analysis was applied as described in panel A using primers specific for exons of the indicated genes. (C-D) Increased 8-oxodG accumulation in the promoters of antioxidant genes in FA cells. FA-A or gene-corrected cells were treated with increasing doses of H2O2 for 2 hours and released into fresh medium for another 12 hours, followed by ChIP using an Ab against 8-oxodG. Precipitated samples were then subjected to PCR using primers specific for promoter regions of (C) GPX1 or (D) TXNRD1 gene. Representative images (left) and quantifications (right) are shown. The intensities of DNA bands were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

Down-regulation of antioxidant genes is associated with a selective increase in promoter DNA damage in FA cells. (A) Increased promoter DNA damage in antioxidant genes in FA-A cells. FA-A cells transduced with empty vector or cDNA-encoding FANCA, as well as a normal control, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by 12 hours of culture in fresh medium. Genomic DNA was isolated followed by FPG cleavage and qPCR using primers specific for the promoters of the indicated genes. The percentage of intact DNA represents the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA. (B) DNA damage in the coding sequences of antioxidant defense genes. The same analysis was applied as described in panel A using primers specific for exons of the indicated genes. (C-D) Increased 8-oxodG accumulation in the promoters of antioxidant genes in FA cells. FA-A or gene-corrected cells were treated with increasing doses of H2O2 for 2 hours and released into fresh medium for another 12 hours, followed by ChIP using an Ab against 8-oxodG. Precipitated samples were then subjected to PCR using primers specific for promoter regions of (C) GPX1 or (D) TXNRD1 gene. Representative images (left) and quantifications (right) are shown. The intensities of DNA bands were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

To further substantiate the observation that the down-regulation of specific genes we observed in FA cells was associated with increased DNA damage to the corresponding promoters, we performed ChIP analysis of the antioxidant gene promoters with a mAb to 8-oxo-dG. The results showed increased accumulation of 8-oxo-dG in the promoters of both GPX1 (Figure 2C) and TXNRD1 (Figure 2D) genes of FA-A cells compared with the genetically corrected cells. Thus, increased promoter DNA damage is associated with reduced antioxidant gene expression in FA cells.

Increased initial oxidative DNA damage to the promoters of antioxidant genes in FA cells

While these data established a correlation between FA deficiency and increased promoter DNA damage, it was not clear whether the FA proteins function in oxidative DNA-damage repair or in protection of the promoter DNA from oxidative damage. To distinguish between these 2 possibilities, we designed 3 sets of experiments. First, we conducted an in vivo DNA-repair assay to measure levels of promoter DNA damage and promoter transcription activity up to 18 hours after H2O2 treatment. Specifically, we examined the repair kinetics of oxidative damage to the promoter on 2 of the down-regulated antioxidant genes, GPX1 and GSTP1. To achieve this, we treated FA-A or genetically corrected cells with H2O2 for 2 hours and allowed the cells to repair oxidative damage in fresh medium. We then isolated genomic DNA and RNA at different time points for a DNA-repair assay and determination of mRNA levels. Although the kinetics for both promoter repair and transcriptional recovery looked similar between FA-A and genetically corrected cells, FA-A cells consistently exhibited higher promoter damage (lower levels of intact DNA) than the genetically corrected cells (Figure 3A left), indicating a higher level of initial damage. Consistent with this, GPX1 mRNA expression was restored at roughly the same rate in both FA-A and genetically corrected cells (Figure 3A right). Similar results were obtained with the GSTP1 gene (Figure 3B). These results suggest no significant deficit in the rate of repair of oxidative DNA damage to these promoters in FA-A cells.

Increased initial oxidative DNA damage to the promoters of antioxidant genes in FA cells. (A) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage to GPX1 promoter. FA-A cells or gene-corrected cells were treated with H2O2 for 2 hours and released for the indicated time intervals followed by genomic DNA or RNA isolation. Samples were then subjected to (left) DNA-damage assay or (right) RT-PCR. (B) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage to GSTP1 promoter. Samples described in panel A were then subjected to (left) DNA-damage assay or (right) RT-PCR. Percentage of intact DNA is the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA. (C) Increased initial oxidative DNA damage in FA-A cells. Cells described in panel A were used for ChIP using an Ab against 8-oxodG and PCR using primers specific for (left) GPX1 or (right) GSTP1 promoter. Representative images (top) and quantifications (bottom) are shown. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (D) Repair efficiency as determined by host cell-reactivation assay. The pSSG-promoter reporter vector containing promoter regions of antioxidant gene GCLC, GPX1, GSTP1, or TXNRD1, as well as control gene GAPDH or β-tubulin, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 1 hour in vitro and then transfected into normal, FA-A, or gene-corrected fibroblasts followed by determination of luciferase activity. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (E) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage to naked promoter DNA. Genomic DNA was isolated from cells described in panel D followed by Fpg cleavage and qPCR using primers specific for the cloned GPX1 promoter. The level of intact DNA represents the efficiency of repair.

Increased initial oxidative DNA damage to the promoters of antioxidant genes in FA cells. (A) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage to GPX1 promoter. FA-A cells or gene-corrected cells were treated with H2O2 for 2 hours and released for the indicated time intervals followed by genomic DNA or RNA isolation. Samples were then subjected to (left) DNA-damage assay or (right) RT-PCR. (B) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage to GSTP1 promoter. Samples described in panel A were then subjected to (left) DNA-damage assay or (right) RT-PCR. Percentage of intact DNA is the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA. (C) Increased initial oxidative DNA damage in FA-A cells. Cells described in panel A were used for ChIP using an Ab against 8-oxodG and PCR using primers specific for (left) GPX1 or (right) GSTP1 promoter. Representative images (top) and quantifications (bottom) are shown. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (D) Repair efficiency as determined by host cell-reactivation assay. The pSSG-promoter reporter vector containing promoter regions of antioxidant gene GCLC, GPX1, GSTP1, or TXNRD1, as well as control gene GAPDH or β-tubulin, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 1 hour in vitro and then transfected into normal, FA-A, or gene-corrected fibroblasts followed by determination of luciferase activity. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (E) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage to naked promoter DNA. Genomic DNA was isolated from cells described in panel D followed by Fpg cleavage and qPCR using primers specific for the cloned GPX1 promoter. The level of intact DNA represents the efficiency of repair.

In the second set of experiments, we performed ChIP to assess the repair kinetics of 8-oxo-dG.22 Again, we observed higher level of GPX1 (Figure 3C left) and GSTP1 (Figure 3C right) promoter DNA containing 8-oxo-dG during the first 2 hours after H2O2 treatment and slower clearance of the oxidative DNA adducts in FA-A cells than in corrected cells. Finally, we used a promoter reporter system in a host cell-reactivation assay27 to determine repair efficiency of oxidative DNA damage. We cloned the promoters of 4 antioxidant genes in luciferase reporter plasmids and generated oxidative DNA damage in vitro on the naked gene promoter DNA. We then transfected the treated plasmids into FA-A or gene-corrected fibroblasts, and assayed for promoter transcription activity, which was presumably correlated with repair efficiency of the cells. The results show that activation of in vitro–damaged reporters was reduced for reporters carrying the promoters of all 4 antioxidant genes, compared with reporters containing the GAPDH or β-tubulin promoter (Figure 3D). However, there was no difference in repair efficiency between FA-A and genetically corrected or normal cells. Furthermore, analysis of the repair kinetics of the damage plasmids up to 18 hours posttransfection, using the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based assay, also showed no deficiency of the repair of oxidative DNA damage to the naked promoter DNA in FA-A cells (Figure 3E). Together, these results suggest that exaggerated initial damage rather than reduced repair contributes to elevated levels of promoter DNA damage in FA cells.

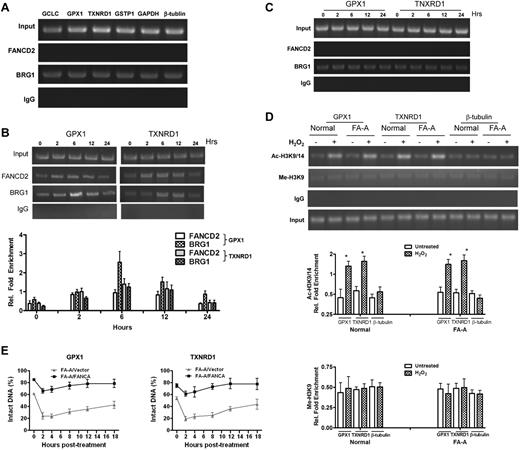

Oxidative stress-induced formation of a FA-BRG1–promoter complex

Because our results suggest that FA proteins play a role in protection of antioxidant gene promoters from oxidative damage and because transcriptional regulation involves chromatin remodeling, we asked whether the FA pathway interacts with the cellular chromatin-remodeling machinery. We performed a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 and BRG1, a chromatin-remodeling ATPase subunit of the BAF complex,28,29 to examine the possibility that oxidative stress would induce simultaneous binding of these 2 factors to the same promoter DNA. The reason for using BRG1 in this study was 2-fold. First, BRG1 is a major factor in chromatin remodeling, which is commonly used in studies involving chromatin remodeling. Second, a previous study had demonstrated an interaction between FANCA and BRG1.30 BRG1 but not FANCD2 bound to the promoters of the antioxidant defense genes, as well as GAPDH and β-tubulin, at steady state (Figure 4A). On challenge with oxidative stress, FANCD2 was recruited to the promoters of GPX1 (Figure 4B top) and TXNRD1 (Figure 4B bottom), which correlated with a significant increase in the binding of BRG1 within the same promoter regions. This induced binding lasted for at least 12 hours after the cells were released from H2O2 treatment (Figure 4B). In contrast, there was no induction of BRG1 binding and no FANCD2 bound to the GPX1 or TNXRD1 promoter in FA-A cells (Figure 4C). These data suggest that the FA pathway may participate in chromatin remodeling and thereby regulating transcription of the antioxidant genes.

Oxidative stress-induced formation of a FA-BRG1–promoter complex. (A) FANCD2 does not bind to the promoters of antioxidant genes in unstressed cells. Untreated normal lymphoblasts were subjected to a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 or BRG1. PCR amplification was performed using primers specific for the promoters of indicated antioxidant or housekeeping genes. (B) FANCD2 is recruited to the GPX1and TXNRD1 promoter regions after H2O2 treatment. Normal cells were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours then released for the indicated time intervals. Proteins were extracted at different time points, followed by a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 or BRG1. Precipitated samples were then subjected to PCR using primers for the promoters of GPX1 or TXNRD1. Representative images (top) and quantifications (botton) were shown. The intensity of the DNA bands was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (C) FA-BRG1-promoter complex was absent in FA cells. FA-A cells were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours then released for the indicated time intervals. Proteins were extracted at different time points, followed by a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 or BRG1. Precipitated samples were then subjected to PCR using primers for the promoters of GPX1 or TXNRD1. (D) Oxidative stress induces accumulation of acetylated histone in the promoters of antioxidant genes of both normal and FA cells. Normal and FA-A cells were treated with or without 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by release into fresh medium. Cells were then subjected to ChIP assay using Abs specific for acetylated histone H3K9/14 (Ac-H3K9/14) or methylated histone H3K9 (Me-H3K9) followed by PCR using primers for the promoter regions of GPX1, TXNRD1, or β-tubulin. Representative images (top) and quantifications (bottom) are shown. The intensity of the DNA bands was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (E) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage in BRG1-bound antioxidant gene promoter. FA-A and gene-corrected cells were treated with or without H2O2 for 2 hours and released into fresh medium for up to 24 hours. ChIP assay using Abs against BRG1 was performed, and the bound DNA fragments were subjected to the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based DNA repair assay using primers specific for the promoter of (left) GPX1 or (right) TXNRD1. Percentage of intact DNA represents the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA.

Oxidative stress-induced formation of a FA-BRG1–promoter complex. (A) FANCD2 does not bind to the promoters of antioxidant genes in unstressed cells. Untreated normal lymphoblasts were subjected to a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 or BRG1. PCR amplification was performed using primers specific for the promoters of indicated antioxidant or housekeeping genes. (B) FANCD2 is recruited to the GPX1and TXNRD1 promoter regions after H2O2 treatment. Normal cells were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours then released for the indicated time intervals. Proteins were extracted at different time points, followed by a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 or BRG1. Precipitated samples were then subjected to PCR using primers for the promoters of GPX1 or TXNRD1. Representative images (top) and quantifications (botton) were shown. The intensity of the DNA bands was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (C) FA-BRG1-promoter complex was absent in FA cells. FA-A cells were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours then released for the indicated time intervals. Proteins were extracted at different time points, followed by a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2 or BRG1. Precipitated samples were then subjected to PCR using primers for the promoters of GPX1 or TXNRD1. (D) Oxidative stress induces accumulation of acetylated histone in the promoters of antioxidant genes of both normal and FA cells. Normal and FA-A cells were treated with or without 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by release into fresh medium. Cells were then subjected to ChIP assay using Abs specific for acetylated histone H3K9/14 (Ac-H3K9/14) or methylated histone H3K9 (Me-H3K9) followed by PCR using primers for the promoter regions of GPX1, TXNRD1, or β-tubulin. Representative images (top) and quantifications (bottom) are shown. The intensity of the DNA bands was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (E) Repair kinetics of oxidative damage in BRG1-bound antioxidant gene promoter. FA-A and gene-corrected cells were treated with or without H2O2 for 2 hours and released into fresh medium for up to 24 hours. ChIP assay using Abs against BRG1 was performed, and the bound DNA fragments were subjected to the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based DNA repair assay using primers specific for the promoter of (left) GPX1 or (right) TXNRD1. Percentage of intact DNA represents the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA.

We next asked whether the FA pathway was essential for a transcriptionally active chromatin in the promoter regions of the antioxidant genes. Acetylation of Histone H3 at residues lysine 9 and 14 (Ac-H3K9/14) is a marker of open or transcriptionally active chromatin, whereas methylation of Histone H3 at lysine 9 (Me-H3K9) is an epigenetic hallmark for closed or transcriptionally silent chromatin.31-34 ChIP using Abs specific for Ac-H3K9/14 and Me-H3K9 shows that oxidative stress-induced accumulation of acetylated H3K9/14 but not methylated H3K9 in the promoter regions of GPX1 and TXNRD1 (Figure 4D). We noted that this oxidative stress-induced enrichment of acetylated H3K9/14 was not observed in the β-tubulin promoter. Interestingly, this change to transcriptionally active chromatin structure in the defined regions of the antioxidant gene promoters occurred in both normal and FA-A cells (Figure 4D). Thus, oxidative stress-induced formation of a transcriptionally active chromatin structure in the promoters of the antioxidant genes is independent of the FA pathway.

The observation that oxidative stress induced the formation of actively transcriptionally active chromatin promoters of the antioxidant genes in FA cells prompted us to test whether the open chromatin DNA was vulnerable to ROS attack. We combined a BRG1 ChIP with the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based DNA repair assay to compare the kinetics of the repair of oxidative damage in the promoters antioxidant genes bound by BRG1 in FA-A and gene-corrected cells. In FA-A cells, we observed a rapid increase in oxidative DNA damage, as measured by a decrease in intact DNA, at BRG1-bound promoters for both the GPX1 and TXNRD1 genes during the first 2 hours after oxidative stress (Figure 4E). In contrast, genetically corrected cells showed much less damage in BRG1-bound promoter DNA at each time point during the posttreatment period than did FA-A cells (Figure 4E). There was a slow repair of this damaged DNA in both cell types after this initial 2-hour period. These results suggest that the formation of the FA-BRG1–promoter complex may protect antioxidant genes from oxidative damage.

Binding of FANCD2− to promoters is independent of BRG1

Given that FANCD2 is recruited to the promoters of antioxidant genes on oxidative stress, we asked whether FANCD2-promoter binding required BRG1. We used shRNA to knockdown BRG1 in normal cells (Figure 5A). We then performed ChIP to determine the binding of FANCD2 to the promoters of the GPX1 and TXNRD1 genes under oxidative stress in cells with knockdown of BRG1. We found that binding of FANCD2 to these promoters was independent of BRG1, as BRG1 knockdown did not reduce the recruitment of FANCD2 to GPX1 or TXNRD1 promoters (Figure 5B). It is noteworthy that in normal cells, BRG1 knockdown resulted in higher H2O2 sensitivity than expression of a control shRNA (supplemental Figure 4A). However, knockdown of BRG1 in FA-A cells did not further increase sensitivity to H2O2 treatment (supplemental Figure 4B).

Binding of FANCD2 to promoters is independent of BRG1. (A) Knockdown of BRG1. Normal lymphoblasts expressing a shRNA for Brg1 or a control shRNA were treated with or without 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours. Cell extracts were then subjected to Western blotting using Abs against BRG1 and actin. (B) Binding of FANCD2 to promoters is independent of BRG1. Cells described in panel A were treated with or without H2O2, followed by a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2. PCR was performed using primers specific for the promoter regions of GPX1, TXNRD1, GAPDH, or β-tubulin.

Binding of FANCD2 to promoters is independent of BRG1. (A) Knockdown of BRG1. Normal lymphoblasts expressing a shRNA for Brg1 or a control shRNA were treated with or without 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours. Cell extracts were then subjected to Western blotting using Abs against BRG1 and actin. (B) Binding of FANCD2 to promoters is independent of BRG1. Cells described in panel A were treated with or without H2O2, followed by a ChIP assay using Abs against FANCD2. PCR was performed using primers specific for the promoter regions of GPX1, TXNRD1, GAPDH, or β-tubulin.

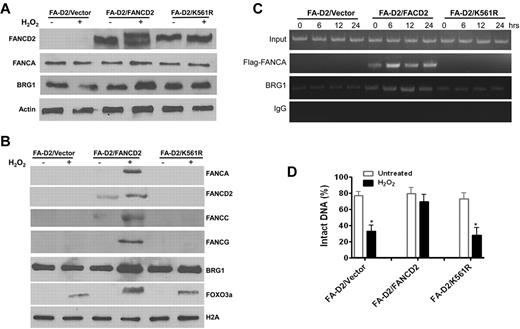

FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of the FA-BRG1–promoter complex and for protection against oxidative damage

Because FANCD2 monoubiquitination is an activating event in the FA pathway in response to DNA damage, we determined whether FANCD2 ubiquitination was required for the formation of the FA-BRG1–promoter complex. We reconstituted FANCD2-deficient cells with WT FANCD2 or with the FANCD2-K561R mutant that cannot be monoubiquitinated26 (Figure 6A). Oxidative stress induced significant recruitment of BRG1 into the total chromatin fraction in WT FANCD2-corrected cells but not in FANCD2-deficient cells or those containing the FANCD2-K561R mutant (Figure 6B). This suggests that increased loading of BRG1 into chromatin in response to oxidative stress may not be specific for antioxidant genes. We also observed that oxidative stress induced chromatin loading of endogenous FANCA, FANCC, and FANCG, as well as the FOXO3a proteins, in cells reconstituted with WT FANCD2 (Figure 6B). ChIP of the GPX1 promoter with a mAb to BRG1 or the Flag-tagged FANCA showed that the FA-BRG1-promoter complex was formed only in cells reconstituted with WT FANCD2 (Figure 6C). Moreover, the combination of a BRG1 ChIP with the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based DNA repair assay shows that the nonubiquitinated FANCD2-K561R mutant failed to protect the GPX1 gene promoter from oxidative DNA damage (Figure 6D). Together, these results indicate that FANCD2 monoubiqitination is required for both FA-BRG1–promoter complex formation and for protection of promoter DNA from oxidative damage.

FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of FA-BRG1–promoter complex. (A) Reconstitution of the FA-D2 cells with WT FANCD2 or the nonubiquitinated FANCD2-K561R mutant. FANCD2-deficient PD20 cell were transduced with retrovirus-expressing empty vector, WT-FANCD2, or the FANCD2-K561R mutant followed by puromycin selection. Stable cell lines were treated with or without H2O2 followed by Western analysis using Abs against FANCD2, FANCA, BRG1, or β-actin. (B) Oxidative stress induces chromatin loading of BRG1 and FA proteins in FANCD2-corrected cells. Cells described in panel A were treated with or without H2O2 followed by chromatin fractionation. Chromatin extracts were then analyzed by Western blotting with Abs against BRG1, FANCA, FANCC, FANCD2, FANCG, or FOXO3a. Histone H2A was included as a loading control. (C) FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of the FA-BRG1-DNA complex. Cells described in panel A were transduced with retrovirus expressing Flag-tagged FANCA, followed by cell sorting for GFP. Sorted cells were then treated with or without H2O2 for 2 hours and released for the indicated hours. ChIP assays using Abs against Flag or BRG1 were followed by PCR amplification using primers specific for the promoter of GPX1. (D) FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the protection of antioxidant gene promoter DNA from oxidative damage. Cells described in panel C were treated with or without H2O2 for 2 hours and released into fresh medium for an additional 12 hours. ChIP assay using Ab against BRG1 was performed, and bound DNA fragments were subjected to the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based DNA-repair assay using primers specific for the promoter of GPX1. The percentage of intact DNA represents the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA.

FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of FA-BRG1–promoter complex. (A) Reconstitution of the FA-D2 cells with WT FANCD2 or the nonubiquitinated FANCD2-K561R mutant. FANCD2-deficient PD20 cell were transduced with retrovirus-expressing empty vector, WT-FANCD2, or the FANCD2-K561R mutant followed by puromycin selection. Stable cell lines were treated with or without H2O2 followed by Western analysis using Abs against FANCD2, FANCA, BRG1, or β-actin. (B) Oxidative stress induces chromatin loading of BRG1 and FA proteins in FANCD2-corrected cells. Cells described in panel A were treated with or without H2O2 followed by chromatin fractionation. Chromatin extracts were then analyzed by Western blotting with Abs against BRG1, FANCA, FANCC, FANCD2, FANCG, or FOXO3a. Histone H2A was included as a loading control. (C) FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of the FA-BRG1-DNA complex. Cells described in panel A were transduced with retrovirus expressing Flag-tagged FANCA, followed by cell sorting for GFP. Sorted cells were then treated with or without H2O2 for 2 hours and released for the indicated hours. ChIP assays using Abs against Flag or BRG1 were followed by PCR amplification using primers specific for the promoter of GPX1. (D) FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the protection of antioxidant gene promoter DNA from oxidative damage. Cells described in panel C were treated with or without H2O2 for 2 hours and released into fresh medium for an additional 12 hours. ChIP assay using Ab against BRG1 was performed, and bound DNA fragments were subjected to the Fpg cleavage/PCR-based DNA-repair assay using primers specific for the promoter of GPX1. The percentage of intact DNA represents the ratio of PCR products after Fpg cleavage to those present in uncleaved DNA.

Discussion

This study links the FA pathway with the oxidative response by identifying a role for the FA proteins in safeguarding the cellular antioxidant defense system. We have provided several lines of evidence to support this link: (1) we show that oxidative stress induces monoubiquitination of FANCD2, a biochemical hallmark of the activation of the FA pathway.26 (2) Several major antioxidant defense genes are significantly down-regulated in BM cells of FA patients in 6 complementation (A, B, C, D1, I, and J) groups. (3) Oxidative stress induces selective DNA damage, particularly 8-oxo-dG, to the promoters of these antioxidant genes in FA cells, which can be prevented by genetic reconstitution of the mutant cells with the appropriate FA gene. (4) The FANCA or FANCD2 protein forms a ternary complex with the chromatin-remodeling factor BRG1 at the promoters of the antioxidant genes in response to oxidative stress. (5) Oxidative stress–induced FANCD2 ubiquitination is required for the formation of the FA-BRG1–promoter complex. (6) The FA-BRG1–promoter complex is essential for the protection of the promoters of antioxidant genes from oxidative damage. Thus, our study identifies a role for the FA pathway in the response to oxidative stress.

One intriguing finding of the present study is our observation that oxidative DNA damage is markedly increased in the promoters of several antioxidant defense genes, compared with their coding regions in lymphoblasts derived from a FA-A patient (Figure 2), suggesting that these promoters were selectively damaged by oxidative radicals in FA-deficient cells. Our results are consistent with recent studies showing that the expression of certain stress response, antioxidant and DNA repair genes is down-regulated in aged human brain samples because of selective damage in the promoters of these genes induced by oxidative stress.21 Promoter regions may be especially vulnerable, as they contain (G + C)–rich sequences that are highly sensitive to oxidative DNA damage and are not protected by transcription-coupled repair.34 This vulnerability may be augmented in FA cells. Indeed, correction of the mutant cells with a functional FANCA protein protected the promoter DNA of the antioxidant genes from oxidative damage. Based on these results, we propose that one critical function of FA proteins under oxidative stress is to regulate the expression of antioxidant defense genes through protecting the gene promoters from oxidative DNA damage.

While these results suggest a correlation between FA deficiency and promoter vulnerability, it remains to be established whether the FA proteins function in oxidative DNA-damage repair or protection of the promoter DNA from oxidative damage. Loss of FA protein function can compromise the damage response/repair process or render chromosomal DNA susceptible to ROS attack, thereby increasing oxidative DNA damage. To distinguish between these 2 possibilities, we conducted time-course studies to assess DNA repair kinetics by examining the levels of promoter DNA damage and promoter transcription activity after H2O2 treatment. We reasoned that if the FA mutant cells consistently showed a delay in kinetics of DNA damage repair as evidenced by the slower clearance of the oxidative DNA damage (8-oxo-dG) and reduced mRNA transcription of the antioxidant defense genes than the gene-corrected cells did, this would suggest that FA cells accumulated high levels of oxidative DNA damage because of impairment of DNA damage response/repair rather than to an increase in the susceptibility of their DNA to oxidative damage. However, our results show the opposite (Figure 3A-B). Furthermore, the host cell-reactivation assay with luciferase reporter plasmids clearly shows that transcription activation or repair rate of the naked reporter plasmids damaged in vitro was not reduced for the reporters derived from the promoters of the antioxidant defense genes in FA cells compared with the gene-corrected cells (Figure 3C and D). Thus, we argue that FA proteins more likely function to protect the promoter DNA from oxidative damage rather than to repair the damage.

An extensive body of evidence which suggests that FA proteins engage in cellular antioxidant defense supports our present finding. For instance, 3 major FA core complex components, FANCA, FANCC, and FANCG,16-18 were found to interact with a variety of cellular factors that primarily function in oxidative stress signaling. It has been shown that oxidative stress induces the formation of a FA subcomplex containing FANCA and FANCG.35 Furthermore, the FANCC protein interacts with NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase and glutathione S-transferase P1-1,36,37 2 redox enzymes involved in detoxification of reactive intermediates including ROS. Fancc−/− mice deficient in the antioxidative enzyme Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase exhibit defective hematopoiesis.38 Fancc−/− cells also display hyperactivation of ASK1, a serine-threonine kinase that plays an important role in redox apoptotic signaling.39 In addition, FANCG interacts with cytochrome P450 2E1, which is associated with the production of reactive oxygen intermediates, and the mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme peroxiredoxin-3.40,41 Finally, we recently reported that FANCD2 associated with FOXO3a, a master regulator of oxidative stress response.42 Although these observations point to the involvement of FA proteins in oxidative stress response, the molecular mechanism by which FA proteins function to modulate oxidative stress response has not been defined.

In this context, our study indicates for the first time that the FA pathway plays a crucial role in protecting major antioxidant defense genes from oxidative damage. Protection appears to be accomplished through a mechanism involving interaction with the chromatin-remodeling machinery in response to oxidative stress. Indeed, we show that oxidative stress-induced activation of the FA pathway (FANCD2 ubiquitination) is required for the formation of the FA-BRG1-promoter complex. We also showed that this complex is essential for the protection of the antioxidant gene promoters from oxidative damage. BRG1 has been shown to interact with the FANCA protein.30 Furthermore, BRG1 plays a role in the inducible expression of certain antioxidant genes43 and in the transcriptional induction of a subset of IFN-inducible genes through interactions with specific transcription factors such as STATs.44 Our studies, taken together with these reports, suggest that induced recruitment of BRG1 and the FA proteins to the promoters of the antioxidant defense genes by oxidative stress may play a role in the transcriptional induction of these genes.

It is interesting that oxidative stress induces accumulation of acetylated H3K9/14 but not methylated H3K9 in the promoter regions of the antioxidant genes (Figure 4C), suggesting the formation of an actively transcriptional chromatin structure. However, because the levels of acetylated H3K9/14 are comparable in both normal and FA cells, a H2O2-induced change of the chromatin at the promoters of antioxidant genes to a more open state does not seem to fully explain differences in their expression between these cell types. One possibility is that the relationship between histone acetylation and transcription activation may actually be complex and could involve other epigenetic signals. Furthermore, DNA-damage repair could also play a role in transcriptional regulation. It has been suggested that ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling is required for the processing and repair of 8-oxodG in the nucleosomes.45 Alternatively, it is possible that oxidative stress–induced open chromatin DNA requires the coordinate action of chromatin-remodeling machinery and other cellular factors, such as FA proteins, to safeguard the gene promoters from inactivation by oxidative DNA damage. The precise mechanisms responsible for protection of the “open” antioxidant gene promoters from oxidative damage remain to be elucidated but could involve a localized formation of the FA-BRG1–promoter complex. Our present study suggests that the formation of this complex involves oxidative stress-induced FANCD2 monoubiquitination (Figure 6). In this context, our results are consistent with the notion that chromatin response to DNA damage is a major mechanism required to safeguard the integrity of the genome.46

In summary, the present studies demonstrate that the down-regulation of major antioxidant defense genes is selectively associated with increased promoter DNA damage and that the FA pathway functions to protect these genes from oxidative DNA damage through a mechanism involving interaction with the cellular chromatin-remodeling machinery. These findings not only provide a molecular explanation for FA-oxidant hypersensitivity but also suggest new targets for therapeutically exploring the pathogenic role of oxidative stress in human diseases.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Alan D'Andrea (Harvard Medical School) for the pMMP-Puro, pMMP-FANCD2, and pMMP-K561R-FANCD2 retroviral vectors, the Fanconi Anemia Comprehensive Care Center (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center) for BM samples, and the Vector Core of the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center) for the preparation of lentiviruses.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 HL076712 and R01 CA157537. Q.P. is supported by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Scholar award. W.D. is supported by a Fanconi Anemia Research Fund grant and an NIH T32 training grant.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: W.D. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.R., K.C.M., and P.M. performed research and analyzed data; J. Sipple and J. Schick performed research; P.R.A. and S.M.D. designed research; and Q.P. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Qishen Pang, Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: qishen.pang@cchmc.org.

![Figure 1. Down-regulation of antioxidant genes in FA BM cells. (A) Hypersensitivity of FA BM progenitors to H2O2. BM cells from 5 FA-A and 2 FA-C patients, as well as 5 healthy donors, were treated with 100μM H2O2 for 2 hours followed by a colony-forming assay. Colony numbers were counted 10 days after plating. Results are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (B) Hypersensitivity of FA LCLs to H2O2. FA-A LCLs and cells corrected with the FANCA gene were treated with increasing doses of H2O2 for 2 hours followed by culture in fresh medium for an additional 24 hours. Cells were then analyzed for cell survival. (C) BM cells from 5 FA-A, 1 FA-B, 2 FA-C, 1 FA-D1, 1 FA-I, and 1 FA-J patients and healthy donors were used for pathway-specific (oxidative stress and antioxidant defense) array analysis. Eighty-four genes involved in antioxidative stress response were analyzed. The data represent the fold down-regulation of the indicated genes in FA samples relative to healthy donors. Fold down-regulation = −1/(fold difference), where fold difference = [2−ΔΔCt (FA)]/[2−ΔΔCt (healthy)]. (D) RT-PCR analysis of antioxidant gene expression in FA-A BM cells. RNA was extracted from BM cells from 2 FA-A patients and 2 healthy donors followed by RT-PCR analysis. (E) Western analysis of antioxidant gene products in FA-A BM cells. Protein lysates were prepared from cells described in panel B followed by Western blot analysis using the indicated Abs. Relative mRNA and protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The results were plotted after normalization with β-actin as an internal control.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/119/18/10.1182_blood-2011-09-381970/4/m_zh89991289990001.jpeg?Expires=1769170489&Signature=keTTjt8eHwmb3IjwfmQI49i3tPTaijzHfXxj7s1CQJ3ui696pp0Fc9qK-x0SaydPWfB8fl13uNSMwo1u8Ul8LklxJ1VEmaPo9W4cjBnk1YCrO61enPgMK7z1uk2IU-pP99q8q3PgyjZ7Zy1r54YhHGmEm5~3zmpS3JXdmVPWgfs~G7e~Df~0nHpI2qLFo-33RKnmmJWLjej~kg54wuGrnZwfKxtG3mNE7gQH9o~BhsHuVPjDRD2~hhSbH8~cdDgjEN7jX3fi9gr44suVPXz2e7wzKu~GXfIDMbf0beNUvGp4WQiJ13dvoOJCgfXG35ukda7H1F4qGYvjSnPF~JE~0w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)