Abstract

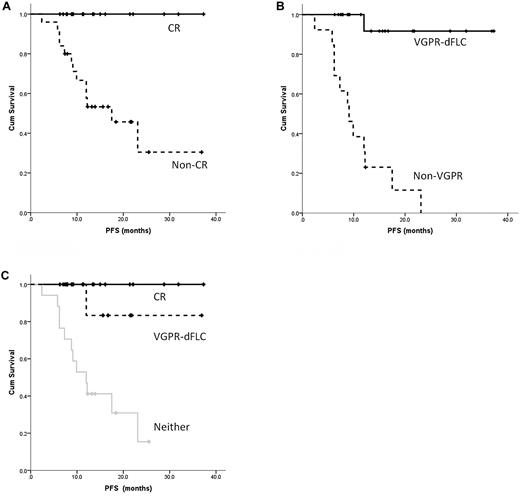

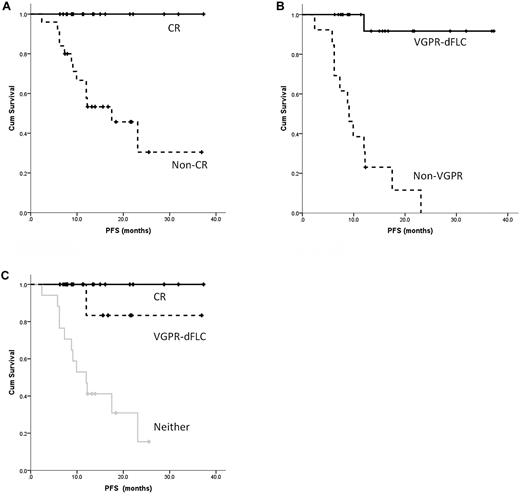

Bortezomib has shown great promise in the treatment of amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis. We present our experience of 43 patients with AL amyloidosis who received cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CVD) upfront or at relapse. Of these, 74% had cardiac involvement and 46% were Mayo Cardiac Stage III. The overall hematologic response rate was 81.4%, including complete response (CR) in 41.9% and very good partial response with > 90% decrease in difference between involved/uninvolved light chain (VGPR-dFLC) in 51.4%. Patients treated upfront had higher rates of CR (65.0%) and VGPR-dFLC (66.7%). The estimated 2-year progression-free survival was 66.5% for patients treated upfront and 41.4% for relapsed patients. Those attaining a CR or VGPR-dFLC had a significantly better progression-free survival (P = .002 and P = .026, respectively). The estimated 2-year overall survival was 97.7% (94.4% in Mayo Stage III patients). CVD is a highly effective regimen producing durable responses in AL amyloidosis; the deep clonal responses may overcome poor prognosis in advanced-stage disease.

Introduction

Bortezomib has been shown to be effective in the treatment of amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis.1-8 Although the efficacy of proteosome inhibitors is based several different mechanisms, of particular relevance to AL amyloidosis is “proteostasis” because of both the excess light-chain production and accumulation of the misfolded proteins.9,10 Based on the success of bortezomib in myeloma treatment regimens, initial retrospective series showing efficacy with bortezomib with or without dexamethasone1,7,11 in AL amyloidosis have laid the groundwork for recent prospective clinical trials showing high response rates but have also raised questions about response durability.4,5 Given the excellent outcomes in myeloma using a steroid/alkylator backbone in combination with bortezomib,12,13 similar strategies have been explored in AL amyloidosis.3,8 In the present study, we describe our experience with the combination of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (CVD) in patients with AL amyloidosis treated in both the upfront and relapsed setting, reporting response and progression-free survival (PFS).

Study design

The primary cohort is a retrospective series of 43 patients from the National Amyloidosis Center in London from January 2006 to March 2011 who underwent detailed prospective evaluation as per standard protocol. The median age of these patients was 54 years and 58% were male. Organ involvement and hematologic and organ responses were defined according to international amyloidosis consensus criteria from 200514 and were as follows: cardiac, 74%; renal, 79%; liver, 23%; peripheral neuropathy, 18%; autonomic neuropathy, 21%; and other organs, 35%. Complete information for staging by the Mayo Clinic criteria15 was available in 39 patients and 46% were stage III based on values obtained before the initiation of CVD (22% of upfront patients and 62% of relapsed patients). The CVD regimen was as follows: bortezomib 1.0 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 4, 8, 11 (increased to 1.3 mg/m2 if well tolerated); cyclophosphamide 350 mg/m2 orally on days 1, 8, and 15; and dexamethasone 20 mg orally on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (increased to 20 mg for 2 days if well tolerated) with the aim of delivering a maximum of 8 cycles. Response was defined as the best hematologic response attained after therapy. Maximal hematologic response was defined as the lowest attained involved light-chain value. Difference in free light chain (dFLC) response has been described previously.16 A dFLC reduction of 50%-90% defined a partial response and a decrease of > 90% defined a very good partial response-dFLC (VGPR-dFLC).

The study has approval from the University College London institutional review board, and written consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. PFS, as estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, was calculated from the start of treatment until relapse,14 death, or last follow-up. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 18 software. All P values were 2-sided with a significance level of .05.

Results and discussion

Initial retrospective series using bortezomib with and without steroids1,7,11 documented response rates (RRs) between 72% and 80%. Recent phase 1 and phase 1/2 trials have corroborated this prospectively, demonstrating an overall RR of 50%-68.8% and complete response (CR) rates of 20%-37.5%, respectively.4,5 Several studies have also investigated the addition of bortezomib to an alkylator/steroid backbone.3,8,17 Current standard approaches using oral melphalan dexamethasone or cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, and thalidomide (CTD) give a RR in the upfront setting 65%-81% with CR of 20%-27%18 but at cost of substantial thalidomide toxicity with CTD or slow response with melphalan dexamethasone. Given the potency and the rapidity of responses seen with bortezomib,4 and because it is relatively well tolerated in patients with cardiac involvement,19 CVD is an attractive combination, especially in patients with advanced disease in whom rapid reductions in circulating amyloidogenic light chains are critical to improving outcome.

In this cohort of patients, the median follow-up time was 14 months. Only 2 deaths occurred and the 2-year overall survival is estimated at 97.7%. The mean time to assessment was 6.0 months and the mean number of cycles given was 5.0 (range, 2-8). Thirty percent of patients developed neuropathy, which resulted in discontinuation of therapy in 14%. Two other patients discontinued therapy because of possible treatment toxicity, 1 with fluid overload and 1 with cardiac decompensation, after 3 cycles each. None discontinued therapy because of cytopenias or other nonhematologic toxicity. Posttherapy stem cell collection was successful in all 3 patients in whom it was attempted. All 43 patients were assessable for hematologic response, with a high overall response rate of 81.4% (CR = 39.5%). These results compare favorably to those from other studies, including those on autologous stem cell transplant (RR = 44%-83% and CR = 22%-41%).20 A significantly higher CR rate was seen in patients treated upfront versus those at relapse (65.0% vs 21.7%; P = .003). This appears superior to other studies in upfront-treated patients (for bortezomib and dexamethasone, RR = 81% and CR = 47%; for CTD, RR = 70% and CR = 27%)11,21 or even autologous stem cell transplant, and is similar to previously documented experience with bortezomib-alkylator combinations (RR = 90% and CR = 62%).3 In responding patients, the time to maximal response was 4.1 months (4.1 months upfront vs 4.2 months at relapse; P = .95). Thirty-five patients were assessable (baseline dFLC > 50 mg/L) for dFLC response, and the dFLC RR was 82.9% (VGPR-dFLC = 51.4%). VGPR-dFLC rates were higher in patients treated upfront versus those treated at relapse (66.7% vs 58.8%; P = .4; Table 1), possibly reflecting increased difficulty in complete eradication of the more resilient clone present at relapse despite evidence of disease control.

Organ responses were also seen in 46% of patients; 11% had cardiac responses, 29% had renal responses, and 40% had liver responses. Of the 30 patients assessable for N-terminal natriuretic peptide type B response,22 33% responded, 14% were stable, and 20% had progression.

The median PFS has not been reached. The 1- and 2-year PFS for the whole cohort was 70.0% and 53.1% respectively, including 74.5% and 66.5% for patients treated upfront and 70.9% and 41.4% for those at relapse, respectively. This compares favorably with the 1-year PFS of 72.2%-74.6% seen in the recent phase prospective 1/2 trial of bortezomib.4 Consistent with data published previously,1,11,18,20,21,23 attaining a CR was correlated with a significant improvement in median PFS (not reached for patients in CR vs 17.5 months for those not in CR; 95% confidence interval, 8.5-26.5; P = .002; Figure 1A) and for a VGPR-dFLC (not reached for VGPR-dFLC vs 9.1 months for non-VGPR patients; 95% CI, 6.0-12.2; P = .026; Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in the median PFS between those attaining a CR and those with a VGPR-dFLC but not a CR (P = .22), but small numbers and the retrospective nature of the study limit interpretation. However, these groups were distinct from those who achieved neither end point (P = .029, Figure 1C). Whereas a CR is the optimal goal of therapy, a dFLC-VGPR is an adequate treatment end point, especially in relapsed patients, and avoids unnecessary treatment toxicity in pursuit of a CR. It is compelling that in our cohort the 1-year PFS and 2-year OS for the Mayo Stage III patients was 74.0% and 94.4%, respectively. This is strikingly different from stage III outcomes in a recent European collaborative study finding a median survival time of 7 months,24 a first hint that bortezomib-induced deep hematologic responses may overcome poor prognostic features of stage III disease.

PFS in patients receiving CVD based on response. (A) Significant improvement in PFS for patients achieving a CR versus a lesser response. (B) Similar results for patients achieving a dFLC-VGPR versus a lesser response irrespective of the monoclonal protein response. (C) Significant improvement in PFS for patients achieving a CR or dFLC-VGPR compared with those with less than dFLC-VGPR.

PFS in patients receiving CVD based on response. (A) Significant improvement in PFS for patients achieving a CR versus a lesser response. (B) Similar results for patients achieving a dFLC-VGPR versus a lesser response irrespective of the monoclonal protein response. (C) Significant improvement in PFS for patients achieving a CR or dFLC-VGPR compared with those with less than dFLC-VGPR.

In summary, CVD is a highly effective combination for the treatment of AL amyloidosis. In this largest series reported to date, the hematologic responses appear to be durable, especially in patients who achieve a CR/VGPR-dFLC. Rapid improvement in organ function is also seen. CVD is stem cell sparing, and functional organ improvement may potentially allow deferred stem cell transplantation in previously ineligible patients. The regime is tolerated by stage III patients, with possible improvement in outcomes in this poor-risk group. Larger phase 3 studies are warranted and are currently under way.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

Presented in abstract form at the 53rd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, December 12, 2011.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinical team at the National Amyloidosis Centre for assistance with patient assessments; Mr David Hutt and Ms Dorothea Gopaul for serum amyloid P component scintigraphy; Mr Toby Hunt and Ms Janet Gilberton for immunohistochemistry; Ms Dorota Rowczenio, Ms Hadija Trojer, and Ms Guosu Wang for genetic sequencing; Ms Marna de Cruz and Dr Babita Pawarova for specialist echocardiography; Dr Nancy Wassef for specialist biochemistry for monoclonal proteins; and all of the hematologists who cared for the patients during the chemotherapy. C.P.V. thanks the Leukemia/Bone Marrow Transplant Program of British Columbia for their fellowship support.

Authorship

Contribution: C.P.V. analyzed the results and produced the figures; T.L., D.F., and L.R. performed the research; C.P.V., S.D.J.G., J.H.P., C.J.W., H.J.L., J.D.G., P.N.H., and A.D.W. cared for the patients and performed the research; C.J.W. assisted with the echocardiography review; and C.P.V. and A.D.W. designed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.D.W. has received honoraria from Jansen Cilag. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christopher P. Venner, National Amyloidosis Centre, Centre for Amyloidosis & Acute Phase Proteins, University College London Medical School, Rowland Hill Street, London NW3 2PF, United Kingdom; e-mail: c.venner@ucl.ac.uk.