Internal tandem duplication (ITD) of the fms-related tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) gene occurs in 30% of acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs) and confers a poor prognosis. Thirteen relapsed or chemo-refractory FLT3-ITD+ AML patients were treated with sorafenib (200-400 mg twice daily). Twelve patients showed clearance or near clearance of bone marrow myeloblasts after 27 (range 21-84) days with evidence of differentiation of leukemia cells. The sorafenib response was lost in most patients after 72 (range 54-287) days but the FLT3 and downstream effectors remained suppressed. Gene expression profiling showed that leukemia cells that have become sorafenib resistant expressed several genes including ALDH1A1, JAK3, and MMP15, whose functions were unknown in AML. Nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice transplanted with leukemia cells from patients before and during sorafenib resistance recapitulated the clinical results. Both ITD and tyrosine kinase domain mutations at D835 were identified in leukemia initiating cells (LICs) from samples before sorafenib treatment. LICs bearing the D835 mutant have expanded during sorafenib treatment and dominated during the subsequent clinical resistance. These results suggest that sorafenib have selected more aggressive sorafenib-resistant subclones carrying both FLT3-ITD and D835 mutations, and might provide important leads to further improvement of treatment outcome with FLT3 inhibitors.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) refers to a genetically and biologically heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by an abnormal increase of myeloblasts in the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) circulation. Chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are the mainstays of treatment, but these modalities have reached an impasse with an overall cure rate of only 30%-40%.1 An attractive strategy is to target specific genetic and biochemical alterations in AML, thereby providing an alternative treatment modality that may improve patient outcome.2,3

FLT3 (fms-like tyrosine kinase-3) is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is highly expressed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. It includes an extracellular domain (ECD), a transmembrane domain (TMD), a juxtamembrane domain (JMD), and 2 tyrosine kinase domains (TKDs) separated by a kinase insert.4 On binding with FLT3 ligand secreted by BM stromal cells, FLT3 undergoes dimerization, phosphorylation, and TKD activation. The FLT3 gene is mutated in approximately 30% of AMLs, particularly those with normal karyotypes, t(6;9), t(15;17), or trisomy 8.5,6 The most common mutation is an internal tandem duplication (ITD) up to a few hundred base-pairs within the JMD. Single-base mutations have also been described, most commonly resulting in a substitution of aspartic acid with tyrosine or less commonly a histidine at residue 835 in the TKD.7,8 At a molecular level, these mutations result in constitutive activation of the FLT3 receptor and hence downstream PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, and JAK/STAT pathways.9,10 The biologic consequences are enhanced proliferation and reduced apoptosis of the myeloblasts, which contribute to leukemogenesis.11,,,–15 Patients with FLT3-ITD respond poorly to conventional chemotherapy and have an inferior prognosis,16,17 particularly in those with a high FLT3-ITD+ cell burden,18 long ITD sequences,19 and multiple FLT3-ITD+ subclones,20 underscoring a pathogenetic role of FLT3-ITD in human AML. In mice, knock-in of a heterozygous FLT3-ITD resulted in a preleukemic model of a myeloproliferative disease, providing an in vivo demonstration of the important role of FLT3 in leukemia initiation.21 We22 and others23,24 have shown that the FLT3-ITD allele can be found in leukemia initiating cells (LICs), as distinguished by their capability of regenerating leukemic progeny in transplanted immunodeficient mice. Therefore, targeting FLT3-ITD might provide a novel approach to therapeutic intervention.

Several clinical trials on multi-TK inhibitors with different FLT3 specificities and in vitro efficacies have been reported, including the use of midostaurin,25 lestautinib,26 tandutinib,27 sunitinib,28 and sorafenib.29 In most studies, clinical efficacy was restricted to FLT3-ITD+ AML and correlated with inactivation of FLT3 phosphorylation.25,30,–32 Complete remission was rare and limited to anecdotal reports in relapsed AML after allogeneic HSCT.33 Furthermore, after the initial response, the leukemia invariably progressed within a few months. In most instances, the mechanism(s) of leukemia progression remained undetermined.34 The FLT3 signaling pathway might have become refractory to inhibition or alternative survival pathways could have been activated in the leukemic cells. Furthermore, FLT3-ITD+ cells might be only a subclone in the leukemia cell population and new clones might emerge during leukemia progression. The definition of these different mechanisms is of potential significance in designing strategies to maximize the therapeutic use of FLT3 inhibitors. In this study, a cohort of patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML refractory to chemotherapy was treated with the multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar; Bayer Healthcare). Leukemia samples from these patients were also prospectively analyzed with molecular and biologic investigations aiming to delineate the mechanisms that accounted for the initial response and subsequent loss of response to sorafenib treatment.

Methods

Patients

From 2009, patients with relapsed or refractory AML that was FLT3-ITD+, whom the treating physicians considered unfit for further induction chemotherapy, were recruited in an open-labeled single-arm study (Table 1). Patients with FLT3-WT AML were excluded. AML was diagnosed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification 2008. Unless otherwise specified, sorafenib 200 mg twice daily to 400 mg twice daily was administered as monotherapy until leukemia progression or HSCT. Treatment dose was reduced in patients with significant toxicity at the discretion of the attending physician. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB; reference no: UW 10-393) at Queen Mary Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment response

BM aspiration and biopsy were performed before sorafenib treatment, 3 to 4 weeks after treatment, and at subsequent time points when clinically indicated. Complete remission (CR) was defined as marrow blasts < 5%, neutrophil count > 1 × 109/L, and platelet count > 100 × 109/L. Complete remission with insufficient hematologic recovery (CRi) was defined as marrow blasts < 5%, trephine biopsy showing no focal prominence of blasts, with neutrophil < 1 × 109/L and platelet count < 100 × 109/L. Near CRi (nCRi) was defined as CRi with focal prominence of blasts in the trephine that could not be enumerated. Nonremission (NR) was defined as failure to achieve any of the above responses. Leukemia progression or loss of treatment response was defined as the emergence of blasts in PB or BM despite continuous sorafenib treatment.

Leukemia cell samples

Low density (LD; < 1.077 g/cm3) cells from BM or PB were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque Plus; Amersham Biosciences) and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. The collection of human samples was IRB-approved (UW 05-183 T/846). Leukemia cells collected before sorafenib treatment were referred to as blastsnaive, and those collected when patients had lost their response to sorafenib as blastsresist.

Cell sorting

Stored primary leukemia samples were thawed and resuspended in Hanks buffered salt solution with 2% FBS. CD34+ cells were isolated from LD cells immunomagnetically (Miltenyi) with more than 95% purity after double-column selection. Alternatively, LD cells were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34 (Beckman Coulter) and phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-CD33 (BD Bioscience) primary antibody and CD33+CD34+ cells isolated using a MoFlo XDP fluorescent activated cell sorter (FACS; Beckman Coulter) with more than 95% purity.

FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD mutational analysis

FLT3-ITD was detected by PCR using primers flanking the JMD and TKD-1 domain encoded in exons 14 and 15.35 Detection of TKD mutation at D835 was performed using PCR followed by allele-specific EcoRV digestion (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The burdens of FLT3-ITD+/D835-mutated cells were determined by a semi-quantitative PCR, in which the reverse primer was labeled with 6-FAM. PCR cycle number was predetermined to fall within the linear region of the amplification curve, and the resulting PCR product fluorescence was analyzed on a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

RNA isolation and microarray analysis

Total RNA of LD and CD33+CD34+ cells were extracted with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen), reversely transcribed to cDNA (SuperScript II; Invitrogen), and stored at −20°C. Microarray analysis was performed on materials from 4 patients. Total RNA from CD33+CD34+ cells was purified with the QIAGEN RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN), and quantified (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer). RNA labeling, array hybridization (Affymetrix Human GeneChip; Affymetrix), staining, and scanning were performed using standard protocols (Affymetrix). Array data were analyzed by GeneSpring GX Version 11 (Agilent Technologies). For comparison of differential gene expression patterns between blastsnaive and blastsresist, the signal ratio of blastsresist to blastsnaive (signalresist/signalnaive) was calculated, and genes consistently up-regulated or down-regulated by more than 1.3-fold in at least 3 of 4 patients were selected for further analysis (supplemental Table 2) and validation by quantitative PCR (supplemental Table 3) with the SYBR Green assay (Applied Biosystems). Experiments were performed in triplicates using ABI7500 Fast PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA expression of the target gene was calculated with the ΔΔCT method with β-actin as the internal control. Validation of protein expression was performed by standard Western blot analysis (supplemental Table 4). All microarray data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE35907.

Aldefluor activity analysis

Aldefluor activity was enumerated as described (StemCell Technology).36 Briefly, LD cells were stained with mouse anti–human CD34-PC5 (Beckman Coulter) and CD33-PE (BD Bioscience), washed, resuspended in Aldefluor assay buffer (106 cells/mL), incubated with activated Aldefluor substrate (5 μL) at 37°C for 30 minutes, washed, and resuspended in Aldefluor Assay Buffer for flow cytometry. Aldefluor intensity was derived by subtraction from that of the diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB) control, which completely inhibited Aldefluor activity.

Xenotransplantation

NOD/SCID mice 6 to 8 weeks old were sublethally irradiated (250 cGy), given an intraperitoneal injection of 200 μg of anti-CD122 antibody (Dr T. Tanaka, Osaka University Medical Center, Osaka, Japan), and then transplanted intravenously with LD or CD33+CD34+ patient cells after 24 hours.37 The presence of human leukemic cells in the BM of the mice was determined at 6, 9, and 12 weeks after transplantation. Mouse BM were evaluated after staining the cells with antibodies against human CD45, CD33, CD19, CD14, CD15, and mouse CD45.1 (BD Bioscience), and human CD34 and CD11b (Beckman Coulter). After lysis of red cells, the BM cells were stained with FITC/PE-conjugated antibodies on ice for 30 minutes and washed. Propidium iodide (PI) was added to enable PI+ (dead) cells to be excluded from these analyses. Cells were then evaluated on a flow cytometer (FC500, BD Bioscience). Human engraftment was defined by the presence of human CD45+ and mouse 45.1-cells in the recipient BM. After engrafted with human myeloblasts, the mice were gavaged daily with sorafenib (10 mg/kg) or vehicle control for 7 to 21 days, after which engraftment level was reassessed. The project was approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals for Teaching and Research (CULATR 837-03, 1587-07) at the University of Hong Kong.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed in mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups of data were evaluated by Mann-Whitney test or Student paired t test. LIC frequencies were calculated by L-Calc Version 1.1 software (StemCell Technologies) and survival of animals transplanted with blastsnaive and blastsresist by Kaplan-Meier analysis. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients and results

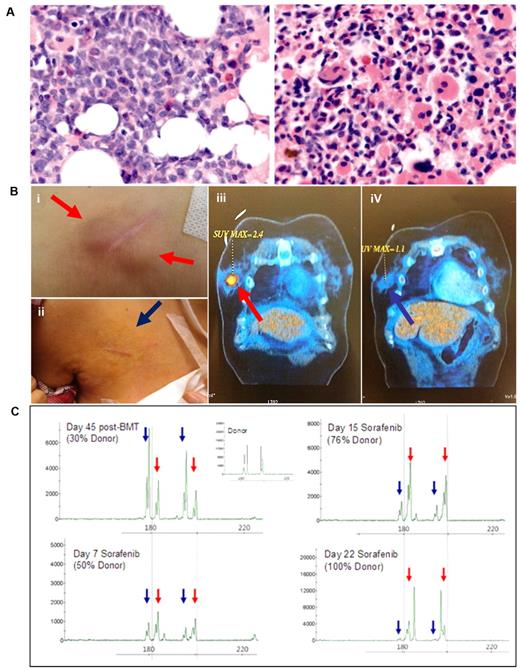

Thirteen patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML were treated with sorafenib. Twelve patients (92%) responded (CRi, n = 6; nCRi, n = 6), with the median time to best response at 27 (21-84) days. As illustrated in patient AML1 (Figure 1A), there was typically predominance of blasts before sorafenib treatment, and a return of normal hematopoietic activity on attaining nCRi after treatement (supplemental Figure 1). BM cellularity at CRi or nCRi in 8 patients was either normal or increased. In most cases, the BM with the clearance of blasts demonstrated granulocytic differentiation with left-shift. Myelocytes and metamyelocytes were abnormal in morphology with reduced cytoplasm and nuclear cytoplasmic asynchrony and mature neutrophils were evident. There was erythroid hypoplasia, megakaryocytic hypoplasia, and significant dysmegakaryopoiesis. BM vasculature was preserved (supplemental Figure 1), which suggests that the antileukemic effects of sorafenib were not associated with inhibition of angiogenesis. Two patients with myeloid sarcoma (MS; central line entrance site, breast) coexisting with BM disease also responded to sorafenib with complete resolution (Figure 1B-C). Of the 4 patients who relapsed after allogeneic HSCT, donor hematopoiesis was completely restored in 1 patient at CRi, as shown by a progressive decrease of recipient and a corresponding increase in donor DNA chimerism (Figure 1C). The only nonresponsive patient had leukemia relapse post-BMT with the lowest FLT3-ITD allele burden at relapse.

Clinical response to sorafenib. (A) BM biopsy of patient AML1, showing predominance of blasts before sorafenib treatment (left), and return of normal hematopoietic activity after treatment at nCRi (right). Nikon Eclipse E800M; eyepiece 10×; objective 40×; numerical aperture of objective lens 0.95; camera Nikon DS cooled camera head DS-5MC & DC camera control unit DS-L2: magnification of picture 400×; software for imaging processing; Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended Version 12.0.4x32. Similar responses were seen in another 11 patients (supplemental Figure 1; original magnification ×400). (B) MS at the central line entrance site in patient AML1 before sorafenib (i) completely resolved after sorafenib treatment for 3 weeks (ii). In patient AML13, a left breast MS (iii) also completely resolved after sorafenib treatment for 3 weeks (iv). (C) Donor and recipient DNA chimerism for patient AML3 who relapsed after HSCT. Red arrows indicated donor and blue arrows recipient specific allele peaks. A progressive decrease of recipient and a corresponding increase in donor DNA chimerism accompanied clinical responses to sorafenib treatment.

Clinical response to sorafenib. (A) BM biopsy of patient AML1, showing predominance of blasts before sorafenib treatment (left), and return of normal hematopoietic activity after treatment at nCRi (right). Nikon Eclipse E800M; eyepiece 10×; objective 40×; numerical aperture of objective lens 0.95; camera Nikon DS cooled camera head DS-5MC & DC camera control unit DS-L2: magnification of picture 400×; software for imaging processing; Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended Version 12.0.4x32. Similar responses were seen in another 11 patients (supplemental Figure 1; original magnification ×400). (B) MS at the central line entrance site in patient AML1 before sorafenib (i) completely resolved after sorafenib treatment for 3 weeks (ii). In patient AML13, a left breast MS (iii) also completely resolved after sorafenib treatment for 3 weeks (iv). (C) Donor and recipient DNA chimerism for patient AML3 who relapsed after HSCT. Red arrows indicated donor and blue arrows recipient specific allele peaks. A progressive decrease of recipient and a corresponding increase in donor DNA chimerism accompanied clinical responses to sorafenib treatment.

Treatment outcome

Of the twelve responding patients, 3 were still in remission, 2 after allogeneic HSCT performed at CRi. Nine patients lost their response despite continuous sorafenib treatment, with a median time to progression of 72 (54-287) days. Three patients went on to receive salvage treatment with another multi-kinase inhibitor sunitinib (up to 50 mg daily), but failed to show any response after at least 3 weeks of treatment.

Persistent FLT3-ITD clone despite CRi

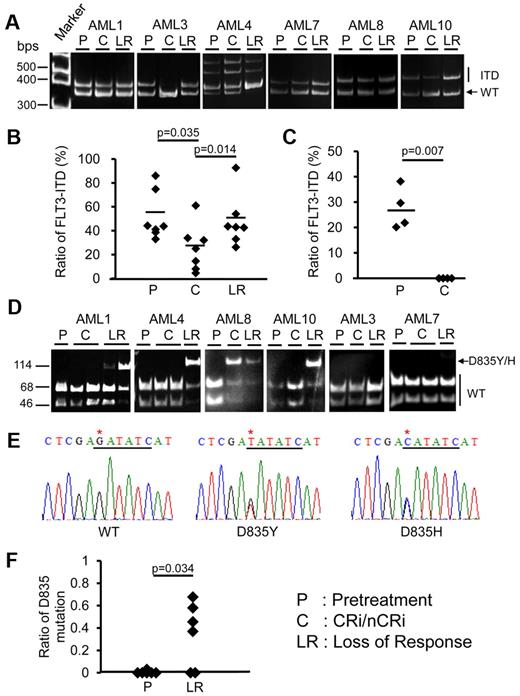

Quantitative analysis of the FLT3-ITD allele burden showed that at CRi or nCRi, FLT3-ITD load persisted but dropped significantly; and resurged when the leukemia progressed (Figure 2A-B). In all cases, the dominant ITD clones before sorafenib treatment persisted at disease progression, as confirmed by DNA sequencing (supplemental Figure 2). AML3 relapsed after HSCT and achieved 100% donor chimerism after sorafenib treatment, so that the ITD clone was undetectable at CRi. As a comparison, materials from 4 patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML treated with chemotherapy outside this study were analyzed. At CR, FLT3-ITD fell below detectable levels (Figure 2C). These results suggest that sorafenib treatment induced differentiation of the FLT3-ITD+ clone.

Prospective analyses of FLT3-ITD and FLT3-D835 mutant clones at different stages of diseases in 6 patients treated with sorafenib. (A) Amplification of FLT3-ITD by PCR. The 329 bp band corresponded to wild-type (WT) FLT3 and the 344-416 bp bands corresponded to ITD. The DNA sequences of these bands were all confirmed by sequencing (supplemental Figure 2). AML3 relapsed after HSCT and achieved 100% donor chimerism after sorafenib treatment, so that the ITD clone was undetectable at CRi. (B) ITD allelic burden after sorafenib treatment persisted but decreased at CRi/nCRi, but resurged when the response was lost. (C) In 4 patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML treated outside this study, chemotherapy reduced the ITD clone to below the detection limit at CR. (D) In 6 sorafenib-treated patients, allele-specific EcoRV digestion showed that the D835 mutation (indicated by arrow) was not detectable before treatment. When the response was lost, however, the D835 mutation emerged in 4 patients (AML1, AML4, AML8, and AML10). In AML8, the mutation was detectable even at CRi. (E) DNA sequencing demonstrated the D835Y mutation in AML1, AML4 and AML10, and D835H mutation in AML8. The EcoRV cut site was underlined in black and point mutation site (G→T/C mutation) was indicated by an asterisk. (F) Quantitative analysis showed that the TKD D835Y/H mutation had emerged when the response to sorafenib was lost.

Prospective analyses of FLT3-ITD and FLT3-D835 mutant clones at different stages of diseases in 6 patients treated with sorafenib. (A) Amplification of FLT3-ITD by PCR. The 329 bp band corresponded to wild-type (WT) FLT3 and the 344-416 bp bands corresponded to ITD. The DNA sequences of these bands were all confirmed by sequencing (supplemental Figure 2). AML3 relapsed after HSCT and achieved 100% donor chimerism after sorafenib treatment, so that the ITD clone was undetectable at CRi. (B) ITD allelic burden after sorafenib treatment persisted but decreased at CRi/nCRi, but resurged when the response was lost. (C) In 4 patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML treated outside this study, chemotherapy reduced the ITD clone to below the detection limit at CR. (D) In 6 sorafenib-treated patients, allele-specific EcoRV digestion showed that the D835 mutation (indicated by arrow) was not detectable before treatment. When the response was lost, however, the D835 mutation emerged in 4 patients (AML1, AML4, AML8, and AML10). In AML8, the mutation was detectable even at CRi. (E) DNA sequencing demonstrated the D835Y mutation in AML1, AML4 and AML10, and D835H mutation in AML8. The EcoRV cut site was underlined in black and point mutation site (G→T/C mutation) was indicated by an asterisk. (F) Quantitative analysis showed that the TKD D835Y/H mutation had emerged when the response to sorafenib was lost.

Heterogeneity of the FLT3 mutated clone

In 6 sorafenib-treated patients in whom paired blastsnaive and blastsresist samples were available, allele-specific EcoRV digestion showed that the D835 mutation (Figure 2D arrow) was not detectable before treatment. However, when the response was lost, the D835 mutation emerged in 4 patients (AML1, AML4, AML8, and AML10). In AML8, the mutation was detectable even at CRi. DNA sequencing demonstrated the presence of the D835Y mutation in AML1, AML4, and AML10, and the D835H mutation in AML8 (Figure 2E). The emergence of TKD D835Y/H mutation at leukemia progression was confirmed by quantitative analysis (Figure 2F), showing that the D835-mutated allele burden was close to 50%, which implies heterozygosity. Other FLT3 mutations, including N841I and Y842C,38,39 were undetectable in blastsnaive or blastsresist (data not shown). These results indicate that with suppression of the FLT3-ITD+ clone under the selection pressure of sorafenib, other clones with FLT3 mutations might emerge.

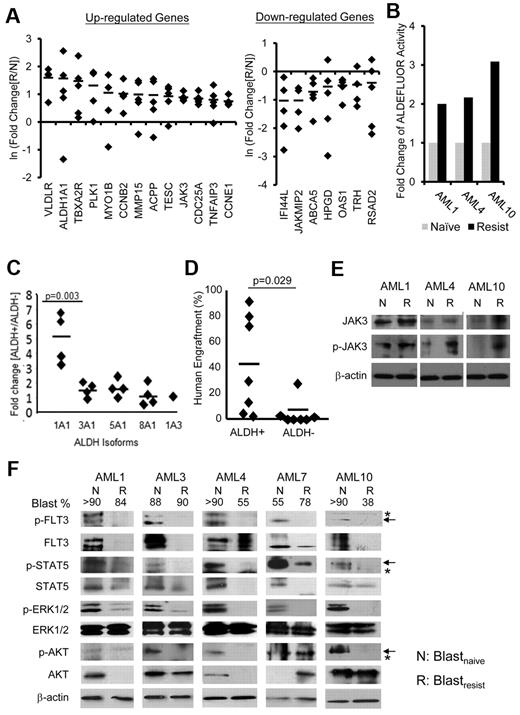

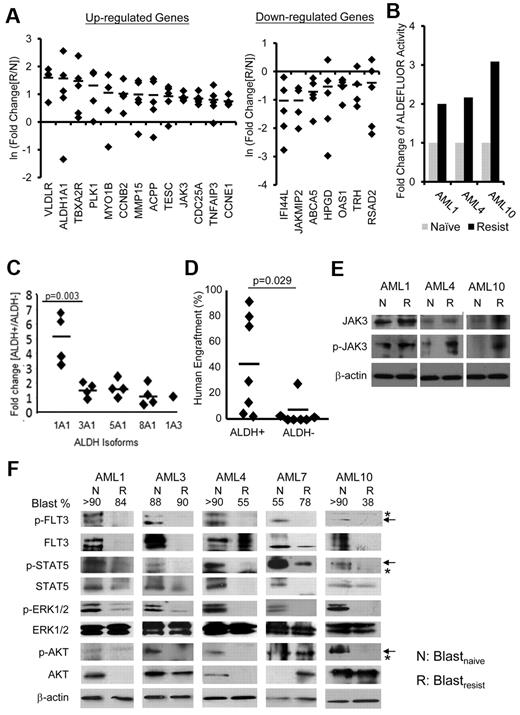

Differential gene expression between blastsnaive and blastsresist

To delineate mechanisms that might account for resistance to sorafenib treatment, gene expression profiling (GEP) was performed for CD33+CD34+ purified blastsnaive and blastsresist (supplemental Table 1). Of the genes up-regulated in blastsresist, some were known to be associated with cell cycle progression (CCNB2 and CCNE1) and antiapoptosis (TNFAIP3); but a significant number had hitherto unknown functions in AML, including ALDH1A1, JAK3, TNFAIP3, and MMP15. The genes that were down-regulated included severalinterferon-induced genes, such as IFI44L, OAS1, and RSAD2. These results were confirmed by Q-PCR analysis (Figure 3A).

Differential gene expression between blastsnaive and blastsresist. (A) Confirmation of microarray data by Q-PCR. Genes associated with cell cycle progression (CCNB2 and CCNE1) and anti-apoptosis (TNFAIP3), and genes the functions of which in leukemogenesis were unknown (ALDH1A1, JAK3, MMP15) were up-regulated; whereas ABCA5, HPGD, and those involved in interferon pathway including IFI44L, OAS1, and RSAD2, were down-regulated in blastsresist. (B) Aldefluor activities were up-regulated by 2- to 3-fold in blastsresist in 3 patients from whom paired blastsnaive and blastsresist samples were available. (C) The CD34+ALDH+ population (of myeloblasts from patients not in this study) preferentially expressed ALDH1A1, as shown by Q-PCR. (D) CD34+ALDH+ population showed superior engraftment in NOD/SCID mice compared with CD34+ALDH− population at equal cell doses. (E) Western blot showing increase in total JAK3 and/or phosphorylated-JAK3 (p-JAK3) in 3 patients when the response to sorafenib was lost. Protein was extracted from CD34+CD33+ myeloblasts (F) Western blot of paired samples from 5 patients. Both total and phosphorylated (p) levels of FLT3 and STAT5 were down-regulated in blastsresist (R) compared with blastsnaive (N). ERK1/2 phosphorylation was specifically down-regulated in blastsresist. The changes in total and phosphorylated AKT proteins were variable. Total and phosphorylated AKT in blastsresist were decreased in AML1, AML3, and AML4 and increased in AML7. Total AKT protein was unchanged in AML10 but p-AKT was decreased. Arrows indicate specific and asterisks nonspecific bands. The numbers on top of the panel indicate the percentage of blasts in the clinical samples. Protein was extracted from LD cells. None of the samples have been cultured or manipulated ex vivo. At progression, or “resistance,” patients were given the therapeutic dosage of sorafenib, although the blood levels had not been measured.

Differential gene expression between blastsnaive and blastsresist. (A) Confirmation of microarray data by Q-PCR. Genes associated with cell cycle progression (CCNB2 and CCNE1) and anti-apoptosis (TNFAIP3), and genes the functions of which in leukemogenesis were unknown (ALDH1A1, JAK3, MMP15) were up-regulated; whereas ABCA5, HPGD, and those involved in interferon pathway including IFI44L, OAS1, and RSAD2, were down-regulated in blastsresist. (B) Aldefluor activities were up-regulated by 2- to 3-fold in blastsresist in 3 patients from whom paired blastsnaive and blastsresist samples were available. (C) The CD34+ALDH+ population (of myeloblasts from patients not in this study) preferentially expressed ALDH1A1, as shown by Q-PCR. (D) CD34+ALDH+ population showed superior engraftment in NOD/SCID mice compared with CD34+ALDH− population at equal cell doses. (E) Western blot showing increase in total JAK3 and/or phosphorylated-JAK3 (p-JAK3) in 3 patients when the response to sorafenib was lost. Protein was extracted from CD34+CD33+ myeloblasts (F) Western blot of paired samples from 5 patients. Both total and phosphorylated (p) levels of FLT3 and STAT5 were down-regulated in blastsresist (R) compared with blastsnaive (N). ERK1/2 phosphorylation was specifically down-regulated in blastsresist. The changes in total and phosphorylated AKT proteins were variable. Total and phosphorylated AKT in blastsresist were decreased in AML1, AML3, and AML4 and increased in AML7. Total AKT protein was unchanged in AML10 but p-AKT was decreased. Arrows indicate specific and asterisks nonspecific bands. The numbers on top of the panel indicate the percentage of blasts in the clinical samples. Protein was extracted from LD cells. None of the samples have been cultured or manipulated ex vivo. At progression, or “resistance,” patients were given the therapeutic dosage of sorafenib, although the blood levels had not been measured.

Biologic consequence of differential gene expression

To validate the biologic effects of differential gene expression between blastsnaive and blastsresist, 2 candidate genes ALDH1A1 and JAK3 were selected. The proportions of ALDH+ cells in blastsresist were increased in 2 (AML1, AML10) but not in the other (AML4) patients (supplemental Figure 3). However, ALDH activities in CD33+CD34+ blastsresist were consistently higher than those of blastsnaive in all cases, thus validating the gene expression findings (Figure 3B). To investigate the biologic functions of ALDH, control CD34+ myeloblasts from 4 cases of AML unrelated to the sorafenib trial were flow-sorted into CD34+ALDH+ and CD34+ALDH− fractions, and the expression patterns of the ALDH isoforms (ALDH1A1, ALDH3A1, ALDH5A1, ALDH8A1, or ALDH1A3) were evaluated. The CD34+ALDH+ fraction preferentially expressed ALDH1A1 (Figure 3C) and exhibited superior engraftment compared with the CD34+ALDH− population when transplanted to NOD/SCID mice at equal cell doses (Figure 3D). For JAK3, Western blot analysis showed that JAK3 phosphorylation was significantly increased in blastsresist, which suggests that up-regulation of JAK3 might reflect activation of its signaling pathway, thereby conferring an alternative survival pathway for blasts that had escaped FLT3 suppression by sorafenib (Figure 3E).

FLT3 and its downstream signaling pathways remained suppressed in blastsresist

To examine whether the loss of response to sorafenib was because of ineffectiveness of sorafenib in suppressing FLT3, blastsresist were examined by Western blot analysis. The patients were treated with sorafenib dosages that were effective in inducing initial CRi at the time of resistance, although plasma levels of sorafenib were not measured. After collection, blastsnaive and blastsresist were washed, ficolled, and cryopreserved without further manipulation or exposure to sorafenib before the generation of protein lysates. FLT3 remained significantly down-regulated at the protein level in blastsresist. Phosphorylated-FLT3 also remained suppressed. The key FLT3 downstream signaling effectors were then examined. STAT5 (signal transducer and activator of transcription) and phosphorylated STAT5 remained significantly down-regulated in blastsresist. Total ERK1/2 protein was unchanged, but phosphorylated-ERK1/2 was significantly down-regulated. The results of total AKT and phosphorylated-AKT were variable. They were down-regulated in patients 1, 3, 4, and 10, but up-regulated in patient 7 (Figure 3F). The overall results indicate that sorafenib remained effective in suppressing FLT3 and its downstream signaling pathways in blastsresist, which suggests that the loss of response to sorafenib was because of escape via activation of other survival pathways.

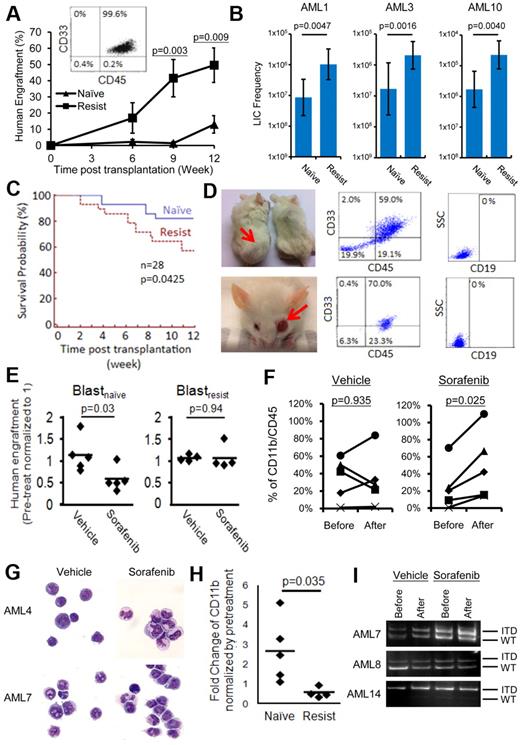

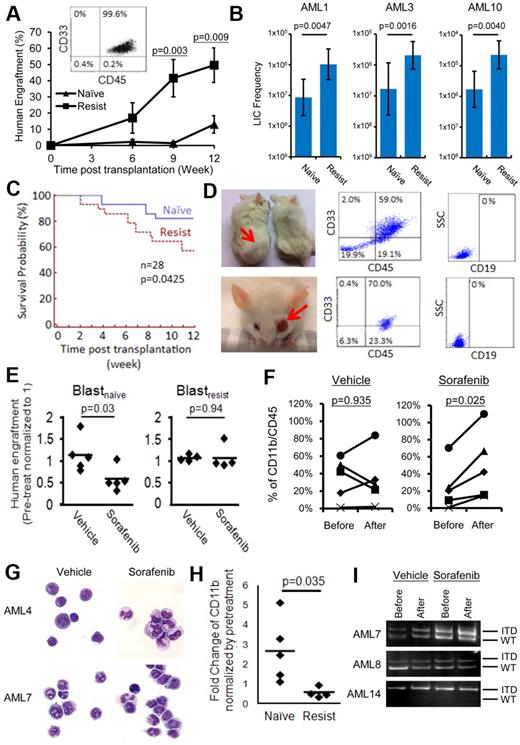

Blastsresist were superior to blastsnaive in LIC activities

To examine whether escaping via alternative signaling pathways may confer a higher proliferative potential, the LIC potential of blastsnaive and blastsresist was compared. At equal doses of CD33+CD34+ cells (0.5-1.5 × 106 cells) or LD cells (1.0-2.5 × 106 cells) injected into NOD/SCID mice, blastsresist exhibited superior leukemia engraftment than blastsnaive at 9 and 12 weeks (Figure 4A). In all cases, the immunophenotype of the engrafting cells were typical of AML with more than 95% human CD45+ cells being CD33+. Limiting dilution assays were performed in 3 patients from whom blastsnaive and blastsresist were sufficient (Figure 4B, supplemental material 5). The results show that the LIC frequencies of blastsresist were 12.0-, 12.2-, and 13.3-fold higher than those of blastsnaive in AML1, AML3, and AML10, respectively. Furthermore, mice transplanted with blastsresist exhibited inferior survivals than those of blastsnaive (Figure 4C). Two of 28 mice transplanted with blastsresist, but none of the 28 mice transplanted with blastsnaive, developed myeloid sarcoma (Figure 4D) with tumor tissue showing CD45+/CD33+/CD19− cells. These observations suggest that blastsresist were more aggressive in vivo.

Recapitulation of the biologic differences between blastsnaive and blastsresist in NOD/SCID mice. (A) When transplanted at equal cell doses, blastsresist exhibited superior engraftment than blastsnaive, which was significant at 9 and 12 weeks after transplantation. The engrafting cells were all CD33+, consistent with the immunophenotype expected of AML. (B) Limiting dilution assays were performed, showing that the LIC frequencies in blastsresist were 12.0-, 12.2-, and 13.3-fold higher than those of blastsnaive in AML1, AML3, and AML10, respectively. (C) NOD/SCID mice transplanted with blastsresist exhibited inferior survivals than those of blastsnaive. All mice that died after 6 weeks after transplantation were confirmed to have > 90% human engraftment in the BM. Twenty-eight mice were transplanted with blastsnaive and another 28 with blastsresist. All mice were killed at 12 weeks after transplantation. (D) Two of 28 mice transplanted with blastsresist developed myeloid sarcoma in the body and the eye, with tumor cells being CD45+/CD33+/CD19−. (E) Sorafenib significantly reduced leukemia engraftment by blastsnaive but not blastsresist in NOD/SCID mice. Each point represented the result from one mouse (5 different experiments from paired samples from 3 patients AML4, 7, 8). (F-G) Sorafenib but not vehicle (DMSO in carboxymethylcellulose) treatment induced differentiation of engrafting cells, as indicated immunophenotypically (F) and morphologically (G). Nikon Eclipse E800M; eyepiece 10×; objective 40×; numerical aperture of objective lens 0.95; camera Nikon DS cooled camera head DS-5MC and DC camera control unit DS-L2; magnification of picture 400×; software for imaging processing Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended Version 12.0.4x32. (H) Sorafenib had no effect on CD11b expression in mice engrafted with blastsresist. (I) PCR for FLT3-ITD in marrow cells from mice engrafted with blastsnaive. In all 3 cases, despite a reduced level of engraftment as shown in panel B after sorafenib treatment, the predominant FLT3-ITD clone persisted, which was also confirmed by quantitative analysis (supplemental Figure 4). Patient AML14 was not included in the clinical trial and has not been treated with sorafenib.

Recapitulation of the biologic differences between blastsnaive and blastsresist in NOD/SCID mice. (A) When transplanted at equal cell doses, blastsresist exhibited superior engraftment than blastsnaive, which was significant at 9 and 12 weeks after transplantation. The engrafting cells were all CD33+, consistent with the immunophenotype expected of AML. (B) Limiting dilution assays were performed, showing that the LIC frequencies in blastsresist were 12.0-, 12.2-, and 13.3-fold higher than those of blastsnaive in AML1, AML3, and AML10, respectively. (C) NOD/SCID mice transplanted with blastsresist exhibited inferior survivals than those of blastsnaive. All mice that died after 6 weeks after transplantation were confirmed to have > 90% human engraftment in the BM. Twenty-eight mice were transplanted with blastsnaive and another 28 with blastsresist. All mice were killed at 12 weeks after transplantation. (D) Two of 28 mice transplanted with blastsresist developed myeloid sarcoma in the body and the eye, with tumor cells being CD45+/CD33+/CD19−. (E) Sorafenib significantly reduced leukemia engraftment by blastsnaive but not blastsresist in NOD/SCID mice. Each point represented the result from one mouse (5 different experiments from paired samples from 3 patients AML4, 7, 8). (F-G) Sorafenib but not vehicle (DMSO in carboxymethylcellulose) treatment induced differentiation of engrafting cells, as indicated immunophenotypically (F) and morphologically (G). Nikon Eclipse E800M; eyepiece 10×; objective 40×; numerical aperture of objective lens 0.95; camera Nikon DS cooled camera head DS-5MC and DC camera control unit DS-L2; magnification of picture 400×; software for imaging processing Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended Version 12.0.4x32. (H) Sorafenib had no effect on CD11b expression in mice engrafted with blastsresist. (I) PCR for FLT3-ITD in marrow cells from mice engrafted with blastsnaive. In all 3 cases, despite a reduced level of engraftment as shown in panel B after sorafenib treatment, the predominant FLT3-ITD clone persisted, which was also confirmed by quantitative analysis (supplemental Figure 4). Patient AML14 was not included in the clinical trial and has not been treated with sorafenib.

Blastsnaive and blastsresist showed similar responses to sorafenib in xenotransplantation

To test whether the effects of sorafenib treatment might be recapitulated in mice, NOD/SCID mice engrafted with blastsnaive and blastsresist were treated with sorafenib (10 mg/kg) by gavage for 1 to 3 weeks. Engraftment by blastsnaive was significantly reduced by sorafenib (Figure 4E). Interestingly, the engrafting leukemia cells showed evidence of differentiation, as shown by a consistent increase in CD11b (Figure 4F) and morphologic evidence of maturation (Figure 4G). Treatment with DMSO (vehicle) had no effect. These observations support the proposition that sorafenib treatment induced differentiation in leukemia cells. In contrast, sorafenib had no effect on engraftment or lineage differentiation in blastsresist, (Figures 4E-F,H). Sorafenib also had no apparent effect on the FLT3-ITD allelic burden of engrafting blastsnaive, which correlated with the persistence of FLT3-ITD clone in clinical observation (Figure 4I, supplemental Figure 4).

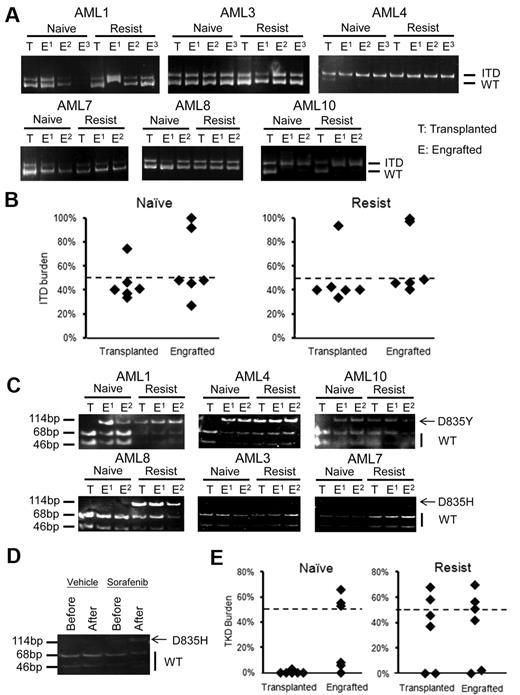

Heterogeneity of FLT3 mutated leukemia cells at the LIC level

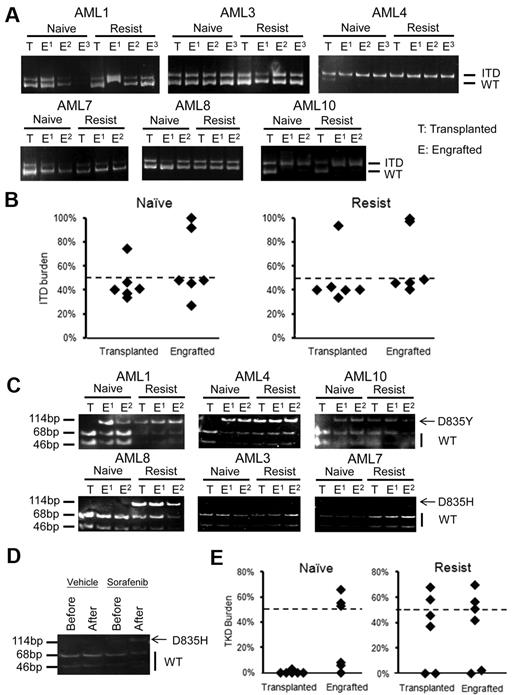

The apparent emergence of clones with FLT3 mutations in blastsresist that were undetectable in blastsnaive suggest that sorafenib might exert a clonal selection pressure. To examine the hierarchical relationship between various subclones, the genotypes of the LIC clones established from blastsnaive and blastsresist were examined. The predominant FLT3-ITD alleles in blastsnaive and blastsresist were identified in their respective LIC clones (Figure 5A). The FLT3-ITD allelic burden of the LIC clone(s) was approximately 50% in patients 1, 3, 7, and 8, which suggests heterozygosity; and 100% in patients 4 and 10 (Figure 5B), which suggests homozygosity because of uniparental disomy. Importantly, the FLT3-D835Y clone that was only detectable in blastsresist in AML1, AML4, and AML10 could be identified in LIC clones derived from blastsnaive,which therefore suggests that these clones had resided in a population of LIC too small to be detectable in the blastsnaive samples (Figure 5C top panel). In AML8, D835H mutation was only detectable in blastsresist and its LIC clone, but not in the blastsnaive samples or the engrafting cells (Figure 5C bottom panel). Intriguingly, when mice engrafted with blastsnaive from AML8 were treated with sorafenib, a new D835 mutation was shown to emerge, recapitulating the preferential outgrowth of double mutation clone in patients under the selection pressure of sorafenib monotherapy (Figure 5D). In all cases showing FLT3-D835Y/H mutation, the allele burden was close to 50%, which implies heterozygosity (Figure 5E).

Hierarchical relationships of FLT3-ITD and D835 clones. (A) In all 6 cases, the predominant FLT3-ITD clones in blastsnaive and blastsresist were detectable in the LIC (the engrafted population). (B) Quantitative analysis of FLT3-ITD allelic burden in the engrafted LIC clone showed heterozygosity in 4 samples and homozygosity in 2 samples. (C) Allele specific enzyme digestion for D835 mutation was performed in both transplanted and engrafted blastsnaive and blastsresist. D835Y mutation was observed in the LIC population but not in the input blastsnaive in AML1, AML4, and AML10. The D835H mutation was not detectable in either transplanted or engrafted blastsnaive, in AML3 and AML7. In AML8, it was detectable in the input and engrafted blastsresist. In the blastsnaive, it was only 3% (Table 1). (D) When mice engrafted with blastsnaive from AML8 were treated with sorafenib, D835H mutation emerged. (E) Quantitative analysis of FLT3-D835 allelic burden confirmed the enrichment of the D835Y clone in the LIC population of blastsnaive in patients AML1, AML4, and AML10. No significant difference before and after transplantation was observed for blastsresist.

Hierarchical relationships of FLT3-ITD and D835 clones. (A) In all 6 cases, the predominant FLT3-ITD clones in blastsnaive and blastsresist were detectable in the LIC (the engrafted population). (B) Quantitative analysis of FLT3-ITD allelic burden in the engrafted LIC clone showed heterozygosity in 4 samples and homozygosity in 2 samples. (C) Allele specific enzyme digestion for D835 mutation was performed in both transplanted and engrafted blastsnaive and blastsresist. D835Y mutation was observed in the LIC population but not in the input blastsnaive in AML1, AML4, and AML10. The D835H mutation was not detectable in either transplanted or engrafted blastsnaive, in AML3 and AML7. In AML8, it was detectable in the input and engrafted blastsresist. In the blastsnaive, it was only 3% (Table 1). (D) When mice engrafted with blastsnaive from AML8 were treated with sorafenib, D835H mutation emerged. (E) Quantitative analysis of FLT3-D835 allelic burden confirmed the enrichment of the D835Y clone in the LIC population of blastsnaive in patients AML1, AML4, and AML10. No significant difference before and after transplantation was observed for blastsresist.

Discussion

In this study, we showed in a cohort of patients with relapsed or therapy-refractory FLT3-ITD+ AML that sorafenib treatment led to a high response rate, resulting in CRi or nCRi in 12of 13 cases. The results were impressive, given that these patients had few other treatment options. because of these responses, some patients were able to undergo potentially curative HSCT. One patient who relapsed after HSCT achieved a CRi with complete restoration of donor DNA chimerism. A similar patient was previously described, who relapsed after HSCT and achieved CR with sorafenib.40 Therefore, screening for FLT3-ITD is warranted in AML patients who have relapsed or refractory leukemia, particularly for those who have an HSCT option. Interestingly, sorafenib treatment also led to resolution of MS in 2 patients. The efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma has been attributed to an anti-angiogenic effect. However, assessment of the posttreatment BM of the responding patients did not show evidence of an antiangiogenesis effect, although whether there might have been such an activity on MS was not evaluated.

In the only patient who did not respond, the FLT3-ITD+ clone was smallest in this cohort and only constituted a very minor fraction of the leukemia cells. This observation was consistent with the in vitro findings, which indicated that FLT3 inhibitors were less efficacious in leukemia cells with a low FLT3-ITD allele burden, compared with those obtained in advanced disease with high allele burden, which might be more dependent on FLT3 signaling.41

Despite clearance or near clearance of leukemic blasts from the BM and regeneration of apparently normal hematopoietic cells, which resulted in a normocellular to hypercellular marrow, FLT3-ITD remained readily detectable. These observations were different from chemotherapy-induced remissions, where FLT3-ITD+ clones were absent. Hence, sorafenib might act at least in part by inducing differentiation of myeloblasts. It was further confirmed by the NOD/SCID xenotransplantation model, in which sorafenib induced differentiation of FLT3-ITD+ myeloblasts in vivo, based on morphologic and immunophenotypic analysis. More recently, in vitro differentiation of leukemia cell lines by sorafenib has also been reported.42 Mechanistically, FLT3 inhibitors might induce differentiation of myeloblasts via inhibition of FLT3 and ERK signaling, leading to de-repression of CEBPα function,43 or up-regulation of a G-protein regulator RGS2, which might increase CEBPα expression.44

Although the initial responses were remarkable, with time the leukemia invariably recurred. At progression, the FLT3 signaling pathway continued to be suppressed and total FLT3 protein expression was also suppressed in blastsresist, which was consistent with the observation that FLT3 mRNA was also down-regulated (supplemental Figure 5). This was not identified in the GEP study because of the limited sensitivity of the microarray based platform. The reduced protein expression of FLT3 and its downstream signaling in blastsresist as demonstrated in the Western blot was not because of dilution of samples by nonleukemic or dead cells. This is because the blast percentages of the blastsresist samples were comparable with those of the blastsnaive samples. Furthermore, the FLT3-ITD allelic ratios in these samples were predictably in the homozygous or heterozygous range, excluding gross contamination by non–FLT3-ITD+ cells. Finally, standard techniques for high-quality protein extraction were closely adhered to, minimizing inadvertent protein degradation during sample handling. Therefore, the suppression of FLT3 and its downstream signaling at leukemia progression implies that the loss of response to sorafenib might be because of an escape via other survival or signaling pathways. An intrinsic resistance of FLT3 receptor to its inhibitor45 or increased level of FLT3 ligand46 might not be involved, as in both circumstances continuous activation of FLT3 signaling at progression would be expected.

To define the alternative survival pathways, a comparison between the GEP of CD33+CD34+ purified blastsnaive and blastsresist showed consistent and significant up-regulation of cell cycle progression (CCNB2, CCNE1), and anti-apoptosis (TNFAIP3) genes when response was lost. These data correlated well with the more aggressive and highly proliferative leukemia seen in patients who relapsed after sorafenib treatment. Furthermore, genes up-regulated in blastsresist that had not been previously associated with leukemogenesis were also identified, including ALDH1A1, JAK3, and MMP15. ALDH1A1 expression correlated with ALDEFLUOR activity, with the latter significantly increased in blastsresist and associated with enhanced LIC activity or frequency in AML.36,47 JAK3 expression has been shown to be up-regulated in precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and a rare gain-of-function mutation of JAK3 has also been reported in AML and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma,48,49 although its pathogenetic role in AML is unclear. We verified that JAK3 gene expression and JAK3 protein phosphorylation were both increased in blastsresist, which implies that the JAK3 signaling pathway might play, as yet, an unidentified role during AML progression. MMP15 has been shown to be up-regulated in breast and prostate cancers, and associated with cancer progression.50,–52 Overexpression of another matrix-metalloproteinase, MMP2, has also been associated with invasiveness of AML cell line in vitro.53 Whether these novel pathways might have mediated the putative protective effects on blastsresist by the BM niche54,55 and therefore represent a target of therapeutic intervention would have to be further investigated.

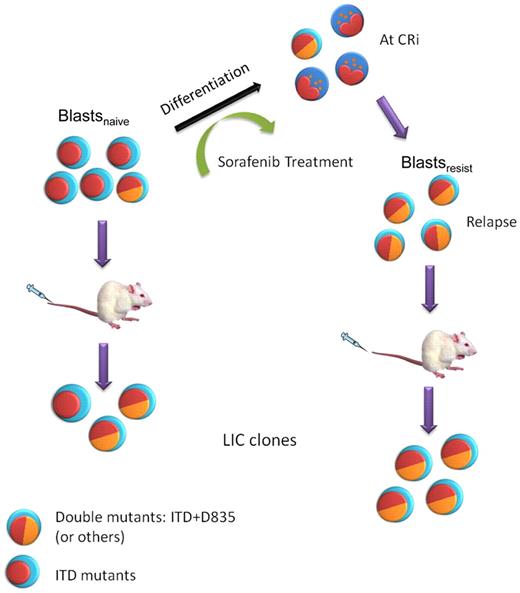

To understand whether these putative survival pathways could arise from competitive clones that evolved under the selection pressure of sorafenib, we analyzed ITD and other mutations of FLT3 in blastsnaive and blastsresist, and their LIC populations. In 4 of 6 patients, the TKD mutation D835Y was not found in blastsnaive, but was selected for during sorafenib treatment to become an important population at relapse (Figure 6). Furthermore, although leukemia cells bearing FLT3-D835Y were not detectable in blastsnaive, they could be amplified and became detectable on engrafting in the NOD/SCID mice in 3 of 6 patients, which suggests that the D835Y mutation was localized in the LIC population. Interestingly, in patient AML8 from whom double mutations were undetectable from the LIC clone in blastsnaive, selection of double ITD-D835Y clones could be demonstrated when the engrafted mice were treated with sorafenib. Therefore, emergence of these double-mutation leukemic clones, although not detectable on presentation as they might have occurred in minor subclones, could be one of the factors accounting for leukemia progression in some cases of FLT3-ITD+ AML. As FLT3 mRNA, FLT3 protein, and the downstream signaling pathways were significantly down-regulated during leukemic progression, the clinical refractoriness of this dominant clone that was selected for by sorafenib treatment was probably because of its ability to survive on unidentified pathways. Whether ITD and D835 double mutations might induce genomic instability56,57 and lead to emergence of these more competitive clones would have to be vigorously tested.

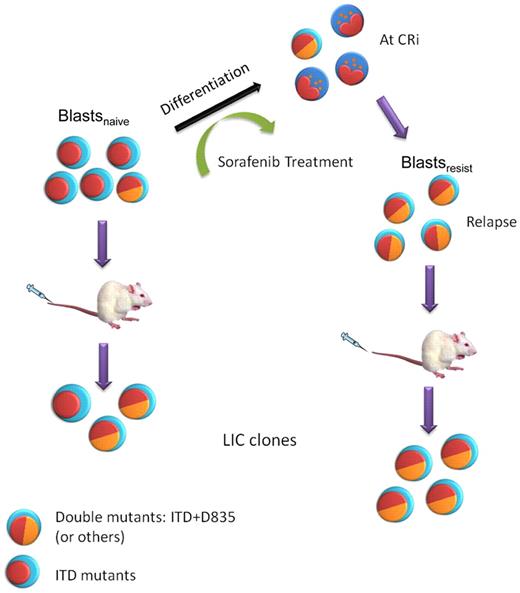

A model of clonal evolution of FLT3-ITD+AML during sorafenib treatment and NOD/SCID engraftment. Multiple clones were present in blastsnaive. Sorafenib induced differentiation in AML, leading to CRi. However, sorafenib resistant clones, in some cases carrying double FLT3-ITD and D835 mutations, emerged and leukemia relapse ensued, giving rise to blastsresist. These double-mutant clones could be further enriched in NOD/SCID mice because of their superior engrafting potential.

A model of clonal evolution of FLT3-ITD+AML during sorafenib treatment and NOD/SCID engraftment. Multiple clones were present in blastsnaive. Sorafenib induced differentiation in AML, leading to CRi. However, sorafenib resistant clones, in some cases carrying double FLT3-ITD and D835 mutations, emerged and leukemia relapse ensued, giving rise to blastsresist. These double-mutant clones could be further enriched in NOD/SCID mice because of their superior engrafting potential.

The overall results of this study showed that sorafenib treatment of FLT3-ITD+ AML led to an initial favorable response, mediated partly by leukemia cell differentiation. However, patients lost response to sorafenib eventually. At this stage, the FLT3 signaling continued to be suppressed, suggesting an escape mechanism via other survival and signaling pathways. GEP results identified pathways that might be valid targets. Using NOD/SCID mice as an in vivo model, FLT3 TKD mutations were shown to be important during clonal evolution under the selection pressure of sorafenib, suggesting this to be an alternative mechanism of leukemia progression. These findings suggest that FLT3 inhibition alone, even with more potent FLT3 inhibitor, may be inadequate in the treatment of AML with FLT3 mutations, and that combination with treatment targeting alternative survival pathways or gene mutations may be needed to improve outcome.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr S. Y. Ha, Dr Harold K. K. Lee, Dr Jocelyn Sim, Dr S. F. Yip, and Dr Herman S. Y. Liu for contributing patient samples to this study.

This work was supported by a grant from the Strategy Research Theme on Cancer Stem Cells at the University of Hong Kong, donations from the S.K. Yee Medical Foundation, Lee Hysan Foundation, and Tang King Yin Research Fund, as well as the Canadian Cancer Society. A.C. was supported by the Croucher Foundation Fellowship and T.K.F. by the Lady Tata Memorial Trust. Sorafenib was provided by Bayer Health and sunitinib by Pfizer Corp.

Authorship

Contribution: C.H.M. conducted most of the experiments and analyzed the data; T.K.F. conducted some of the experiments and analyzed the data; C.H., H.H.C.H., H.C.H.C., and A.C.H.M. conducted some of the experiments, prepared the anti-CD122 murine antibodies, and performed the xenotransplantation; W.W.L.C. reviewed and prepared the histologic slides and immunostaining on human BM; S.L. analyzed the gene expression profile; A.M.S.C. and C.E. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; Y.L.K. designed the research, managed the patients, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and A.Y.H.L. designed the research, managed the patients, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yok Lam Kwong or Anskar Y. H. Leung, Room K417, K Block, Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Pok Fu Lam Road, Hong Kong; e-mail: ylkwong@hku.hk or ayhleung@hku.hk.