Abstract

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a major complication of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation that is associated with a diminished quality of life. The oral cavity is frequently affected, with a wide variety of signs and symptoms that can result in significant short- and long-term complications ranging from mucosal sensitivity and limited oral intake to secondary malignancy and early death. This article provides a comprehensive approach to the diagnosis and clinical management of patients with oral cGVHD, with particular attention to differential diagnosis, control of symptoms, and prevention of and screening for secondary complications. The clinical considerations and recommendations presented are intended to be practical and relevant for all clinicians involved in the care of patients with oral cGVHD, with the ultimate goal of improving care and outcomes.

Introduction

Despite advances in HLA matching and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis, chronic GVHD (cGVHD) continues to be a significant complication of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and remains the leading cause of nonrelapse mortality.1 Although cGVHD is a systemic condition mediated by alloreactive donor-derived lymphocytes, the clinical impact and associated morbidity are typically experienced at the level of the individual target organ, where localized and anatomically distinct immune activity (eg, mucosal immunity) may play a major pathogenic role in mediating disease activity.2-5 The oral cavity is one of the most frequently affected sites, with a wide variety of signs and symptoms that can result in significant short- and long-term complications. These range from mouth sensitivity and difficulty eating, to secondary malignancies contributing to early death.6-8

Transplant specialists generally provide primary management for cGVHD yet typically receive little, if any, formal oral medicine education during their clinical training, leaving them with minimal experience in examining, diagnosing, and managing oral diseases. Furthermore, general dentists are typically not well versed in complex oral medical conditions, particularly in the field of HCT and cGVHD. This results in a paucity of specialists adept at managing these patients. The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive approach to the clinical management of patients with oral cGVHD, with particular attention to practical considerations, control of symptoms, and prevention of and screening for secondary complications. Our intent is for this resource to provide relevant and effective guidance for clinicians involved in the care of patients with oral cGVHD, with the ultimate goal of improving oral cGVHD-related health outcomes.

Epidemiology of oral cGVHD

The oral cavity is one of the most frequently affected anatomic sites in cGVHD, with 1 large single-center study reporting ∼ 80% of patients with cGVHD demonstrating oral involvement and a recent analysis from the Chronic GVHD Consortium reporting similar trends.6,9 Oral features are generally present at the time of cGVHD diagnosis and may represent the initial clinical manifestations, and oral involvement is probably the most common location of single-site disease. Although the overall incidence of cGVHD in pediatric patients is lower than in adults, the extent, severity, and complications of oral cGVHD can be equivalent in all age groups.10,11 Although a number of factors have been associated with an increased risk of developing cGVHD after allogeneic HCT (eg, antecedent acute GVHD, HLA mismatch, stem cell source), there are no known risk factors specific to oral cGVHD.12

Clinical features of oral cGVHD

Oral cGVHD is typically thought of as a singular clinical entity; however, in reality, there are unique clinical features associated with mucosal, salivary gland, and sclerodermatous involvement, each of which can contribute to significant morbidity and late complications. Correct diagnosis and appropriate and effective management depend first and foremost on a clear understanding of the associated clinical features and their distinct characteristics.

Mucosal disease

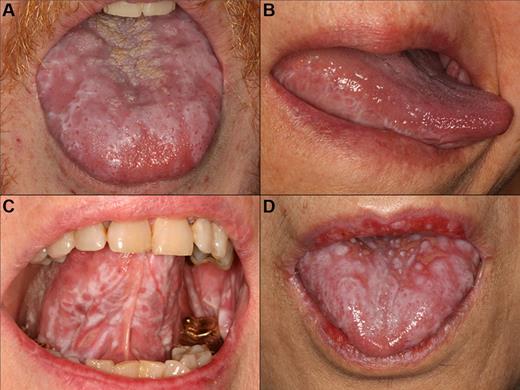

Oral mucosal cGVHD is characterized by lichenoid inflammation that can involve all intraoral sites, but particularly affects the tongue and buccal mucosa.8,13,14 Clinical signs include white hyperkeratotic reticulations and plaques, erythematous changes, and ulcerations, which can range from very limited disease with only mild reticulation to more extensive disease with painful ulcerations (Figures 1 and 2). Of note, the soft palate is infrequently affected, and cGVHD changes rarely extend posteriorly to the oropharynx (Figure 3).13 The lips are also a frequent site of involvement, demonstrating the same changes observed intraorally, and can be a source of significant discomfort (Figure 4).

cGVHD lichenoid features of the tongue. Reticular cGVHD of the (A) tongue dorsum and (B) ventrolateral tongue demonstrating typical hyperkeratotic striations and plaque-like changes. More extensive involvement with heavy reticulation and associated ulcerations of the (C) ventral tongue and (D) tongue dorsum, with various degrees of erythema. There is prominent involvement of the lips in panel D, which stops abruptly at the vermillion border.

cGVHD lichenoid features of the tongue. Reticular cGVHD of the (A) tongue dorsum and (B) ventrolateral tongue demonstrating typical hyperkeratotic striations and plaque-like changes. More extensive involvement with heavy reticulation and associated ulcerations of the (C) ventral tongue and (D) tongue dorsum, with various degrees of erythema. There is prominent involvement of the lips in panel D, which stops abruptly at the vermillion border.

cGVHD of the buccal mucosa with extensive multifocal areas of ulceration interspersed with erythema and reticulation.

cGVHD of the buccal mucosa with extensive multifocal areas of ulceration interspersed with erythema and reticulation.

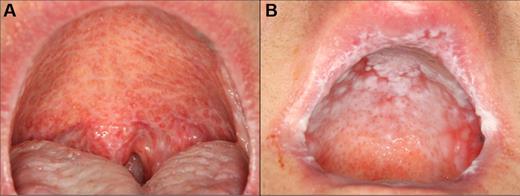

cGVHD affecting the palate. (A) Extensive reticulation of the entire hard and soft palate, extending to the uvula. (B) Hyperkeratotic involvement of the hard palate with associated erythema and focal areas of ulceration, with minimal soft palate extension. Note the heavy reticulation of the lips.

cGVHD affecting the palate. (A) Extensive reticulation of the entire hard and soft palate, extending to the uvula. (B) Hyperkeratotic involvement of the hard palate with associated erythema and focal areas of ulceration, with minimal soft palate extension. Note the heavy reticulation of the lips.

cGVHD of the lips. (A) Reticular changes only. (B-C) Extensive involvement with reticulation, erythema, and focal ulcerations. (D) Heavy scaling and painful peeling of the lips.

cGVHD of the lips. (A) Reticular changes only. (B-C) Extensive involvement with reticulation, erythema, and focal ulcerations. (D) Heavy scaling and painful peeling of the lips.

The primary symptom associated with oral mucosal cGVHD is sensitivity to otherwise normally tolerated foods, drinks, and oral hygiene products, with most patients reporting little if any oral discomfort at rest. Foods and drinks that are consistently reported by patients as being painful include those that are spicy (eg, even a very small amount of pepper), acidic (eg, fruits, salad dressing), and hard/rough/crunchy; however, in some patients there is universal sensitivity such that oral intake becomes severely restricted. Although symptoms are generally worse with more severe clinical manifestations, this is not universally true, and patients with only reticular changes may be as or more symptomatic than patients with ulcerations.13 When there are prominent reticular changes affecting the buccal mucosa, patients may report a sensation of mouth tightness and a reduced ability to open the mouth (Figure 5). This should be differentiated from oral tightness because of primary sclerotic cutaneous cGVHD or secondary to mucosal scarring (see “Sclerotic disease”).

cGVHD of the buccal mucosa with extensive and thick hyperkeratosis making the mouth feel “tight” with limited opening.

cGVHD of the buccal mucosa with extensive and thick hyperkeratosis making the mouth feel “tight” with limited opening.

Salivary gland disease

Unlike oral mucosal cGVHD, which presents with prominent features that are easily recognized clinically, involvement of the salivary glands tends to be less obvious and is probably under recognized. In addition, some patients experience significant xerostomia (subjective complaint of oral dryness) after HCT conditioning (most commonly associated with total body irradiation or prior irradiation to the head and neck), and this may persist through the period when salivary gland cGVHD develops, making onset and diagnosis less evident.15,16 Saliva plays a critical role in mastication and swallowing, taste, speech, tooth remineralization, maintaining oral pH balance, and prevention of oral infection.17 Any compromise in salivary gland function can adversely affect any of these essential functions.

cGVHD of the salivary glands results in both quantitative and qualitative changes in salivary production, composition, and output. Extraoral salivary gland swelling, with or without discomfort, can develop secondary to obstructive changes but is exceedingly rare. Intraoral examination may demonstrate dry-appearing oral mucosa with lack of floor-of-mouth pooling (Figure 6); however, it is quite common to encounter patients with significant xerostomia that present with otherwise normal clinical findings, supporting the central role of qualitative changes. Salivary flow measurement, or sialometry, is typically reserved for research purposes and is not routinely performed in clinical practice because the procedure is highly technique sensitive and objective measures do not necessarily correlate with patient symptoms.18,19 A modified test using the Schirmer eye strips in the mouth has been proposed but is not widely used for similar reasons.20

Salivary gland cGVHD with desiccated appearing palatal mucosa secondary to severe salivary gland hypofunction.

Salivary gland cGVHD with desiccated appearing palatal mucosa secondary to severe salivary gland hypofunction.

Patients with salivary gland cGVHD are at risk for developing secondary infectious complications because of diminished anticariogenic and antifungal activities. In addition to the effects on teeth (Figure 7), patients are at significant risk for recurrent oral candidiasis, especially if there is ongoing topical corticosteroid therapy for management of mucosal cGVHD, which suppresses mucosal immunity (see “Infections”; Figure 8).

Rampant cervical dental caries affecting all of the teeth in a patient with cGVHD of the salivary glands. Demineralization changes (arrow) appear chalky white.

Rampant cervical dental caries affecting all of the teeth in a patient with cGVHD of the salivary glands. Demineralization changes (arrow) appear chalky white.

Oral candidiasis in patients with oral cGVHD. (A) Florid pseudomembranous candidiasis in a patient using intensive topical clobetasol solution rinses. (B) Thick, plaque-like confluent pseudomembranous candidiasis in a patient using combined clobetasol and tacrolimus solutions. (C) Erythematous candidiasis in a patient with severe cGVHD-associated salivary gland hypofunction and a full maxillary denture. (D) Typical patchy pseudomembranous candidiasis of the palate in a patient rinsing with dexamethasone solution.

Oral candidiasis in patients with oral cGVHD. (A) Florid pseudomembranous candidiasis in a patient using intensive topical clobetasol solution rinses. (B) Thick, plaque-like confluent pseudomembranous candidiasis in a patient using combined clobetasol and tacrolimus solutions. (C) Erythematous candidiasis in a patient with severe cGVHD-associated salivary gland hypofunction and a full maxillary denture. (D) Typical patchy pseudomembranous candidiasis of the palate in a patient rinsing with dexamethasone solution.

An additional feature of oral cGVHD is the development of recurrent superficial mucoceles (Figure 9).21 These are generally painless mucus-filled blisters that develop primarily on the palate but can also be observed on the labial and buccal mucosa and tongue, or wherever there are minor salivary glands. These lesions develop secondary to inflammation and “leakiness” of minor salivary gland ducts and often present acutely when eating because of stimulation of the glands. There is almost complete resolution shortly thereafter, making these primarily a nuisance. Superficial mucoceles can be seen in the context of both mucosal and salivary gland cGVHD, suggesting that the underlying inflammation may be secondary to generalized mucosal involvement or because of direct salivary gland tissue targeting. These common recurrent lesions are not of viral etiology and should be distinguished from recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection.

Sclerotic disease

Sclerotic changes affecting the oral cavity are rare but, when present, may be associated with significant morbidity. Signs and symptoms include limited mouth opening, pain, secondary ulceration, and impaired oral hygiene (Figure 10). Involvement can be the result of perioral and facial skin sclerosis, typically as an extension of more generalized sclerotic changes. Alternatively, it can arise from primary mucosal sclerosis, typically developing as a sequela of long-standing severe ulcerative mucosal cGVHD, causing band-like fibrosis in the posterior buccal mucosa.

Orofacial sclerotic cGVHD. (A) Fibrous band formation of the right buccal mucosa secondary to longstanding mucosal cGVHD, with limited opening and secondary gingival injury because of tightness. (B) Generalized skin and myofascial fibrosis with intense and painful secondary myospasms and limited opening.

Orofacial sclerotic cGVHD. (A) Fibrous band formation of the right buccal mucosa secondary to longstanding mucosal cGVHD, with limited opening and secondary gingival injury because of tightness. (B) Generalized skin and myofascial fibrosis with intense and painful secondary myospasms and limited opening.

Other associated conditions

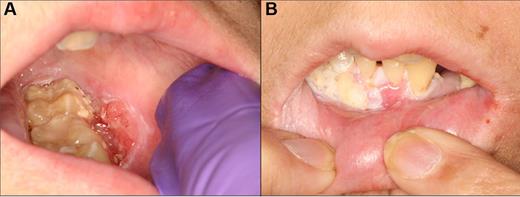

There are several other oral lesions and conditions that must be recognized and differentiated from cGVHD. Recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection can present as solitary or multiple ulcerative lesions affecting any intraoral site, and breakthrough infections may occur despite antiviral prophylaxis (Figure 11). Therefore, herpes simplex virus should be considered when there is new onset of markedly painful ulcerative lesions and oral swabs should be obtained for viral culture and/or direct fluorescence antibody test.22 Rarely, patients being treated with rapamycin may develop painful aphthous-like ulcerations that are distinct from mucosal cGVHD. These lesions are culture-negative and do not respond to antiviral therapy.23 Calcineurin inhibitor-associated fibrovascular polyps are rare and present as exophytic ulcerated nodular masses.24 Surgical excision is generally therapeutic, although recurrence can occur. Verruciform xanthoma is a rare benign inflammatory lesion that clinically resembles squamous cell carcinoma and requires biopsy for diagnosis.25 Patients with oral cGVHD are at a significantly increased risk for developing oral squamous cell carcinoma, which can present with a wide array of clinical features, including ulceration, induration, and exophytic and endophytic growth patterns (Figure 12).26-29 These lesions may be difficult to discern from mucosal cGVHD changes; thus, referral to a specialist for biopsy is essential for timely and appropriate therapy.

Recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection of the hard palate with 3 distinct, clustered ulcerations in a patient with a prior history of, but not currently active, oral cGVHD.

Recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection of the hard palate with 3 distinct, clustered ulcerations in a patient with a prior history of, but not currently active, oral cGVHD.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the left posterior buccal vestibule in a 14-year-old girl that was 6 years after transplantation, with a prior history of severe mucosal cGVHD. (A) Ulcerated, exophytic, and indurated lesion of the vestibule that was treated with wide excision and chemoradiation therapy. (B) Localized recurrence that was evident within weeks of completion of therapy.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the left posterior buccal vestibule in a 14-year-old girl that was 6 years after transplantation, with a prior history of severe mucosal cGVHD. (A) Ulcerated, exophytic, and indurated lesion of the vestibule that was treated with wide excision and chemoradiation therapy. (B) Localized recurrence that was evident within weeks of completion of therapy.

Diagnosis of oral cGVHD

Diagnosis of oral cGVHD relies mostly on history, clinical examination findings and the context of onset of signs and symptoms (eg, time since HCT, tapering of immunosuppressive regimen, other affected areas of cGVHD involvement). The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease introduced standardized criteria for the diagnosis of oral mucosal and salivary gland cGVHD, although these were based on expert opinion and have not been validated prospectively (Table 1). Diagnostic features sufficient to establish a clinical diagnosis of oral (mucosal) cGVHD include lichenoid or reticular lesions and hyperkeratotic plaques, with erythematous and ulcerative changes (in the absence of lichenoid reticulations) considered “distinctive” but not diagnostic.30 Oral mucosal and/or minor salivary gland biopsies can help support a diagnosis when not otherwise clinically evident, but this is generally not necessary in clinical practice.31 In general, the diagnosis of oral mucosal cGVHD is more straightforward than salivary gland cGVHD because of the prominent and, in many cases, quite obvious clinical features and more limited differential diagnosis. The National Institutes of Health staging score is a simple measure of the functional impact of oral cGVHD and can be useful in assessing change in severity over time (Table 2).

It is essential that oral cGVHD be differentiated from other common oral conditions that do not require therapy. These include: linea alba, which is a hyperkeratotic white line along the bite plane; cheek biting lesions, which have a diffuse and “ragged” white appearance; leukoedema, which appears white and faintly reticular but disappears entirely with stretching of the tissue; and geographic tongue, which presents with atrophic and erythematous patches surrounded by circular white hyperkeratotic changes that wax and wane on a regular basis. Other than tissue biopsy (which is not routinely performed), there are no laboratory tests that can confirm the diagnosis of oral cGVHD; therefore, good diagnostic skills based largely on experience are critical. Oral medicine specialty consultation can be useful in cases with atypical presentations or equivocal findings, especially when symptoms appear to be disproportionate to clinical features.

Management of oral cGVHD

cGVHD, especially when there is multisystem involvement, requires systemic corticosteroids and/or other immunomodulatory agents. In many cases, this will adequately control oral disease symptoms. Whereas the median duration of systemic immunosuppressive therapy for the management of cGVHD is 2-3 years, there are no available data on the long-term course and additional management strategies for therapy of oral cGVHD.32 In our experience, a significant proportion of patients require prolonged intensive ancillary therapy for management of oral cGVHD, even after systemic immunosuppressive therapies have been stopped. The accessibility of the oral cavity to topical and local therapies is advantageous because persistent oral disease can often be controlled without systemic immunosuppression. Similarly, when cGVHD presents with only limited oral involvement, ancillary measures alone may be sufficient without the need for systemic therapy.

The goals of oral cGVHD therapy include reduction of symptoms, resolution of painful lesions, and screening for, prevention of, and management of secondary complications (Tables 3 and 4). All patients should be educated on the importance of maintaining good oral hygiene, with daily tooth brushing and flossing and regular professional dental cleanings at least twice annually. Although there is no indication for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients actively being treated for cGVHD, most centers restrict elective dental visits during the first year after transplantation because of precautions during immune reconstitution.33 Patients with oral cGVHD often complain of intense sensitivity to toothpaste (because of sodium lauryl sulfate and flavoring agents) and should be instructed to use a children's toothpaste as these are sodium lauryl sulfate-free and less intensely flavored. The use of heavily flavored mouthwashes, especially those that contain alcohol, should similarly be avoided because of general intolerability. Patients may need to avoid acidic, spicy, rough/hard, carbonated and hot food/drinks; individual tolerability is highly variable, and many patients find it difficult to eat away from home where food choices are limited and often highly seasoned. Although not routinely indicated, some patients may require nutritional counseling.

Oral mucosal cGVHD

The primary objective in managing oral mucosal cGVHD is to reduce and/or control symptoms, rather than focusing on improvement of signs of disease (eg, “healing” ulcers). This is a critical concept as the visible clinical features may remain largely unchanged despite significant symptomatic improvement; and in such cases, this should be considered a successful treatment outcome. Usually, however, disease signs improve in concert with reduction of symptoms.

The mainstay of oral mucosal cGVHD management is intensive topical corticosteroid therapy.33 The efficacy of topical therapies depends on active medication penetrating into the oral mucosa from the “outside in” and downregulating lymphocyte activity in the subepithelial connective tissue, at the site of tissue inflammation.34 The potency of the agent, the vehicle and formulation in which it is delivered, and the duration/frequency of application are all critical factors in determining the effectiveness of topical therapies. Despite active research in the field of mucosal drug delivery, to date there are few, if any, prescription topical agents that are intended and/or approved for intraoral mucosal therapy.35 A critical consideration is that the oral cavity is a wet environment because of salivary flow, and topical therapies are quickly and easily diluted and/or washed away by normal oral function, especially in highly affected sites, such as the buccal mucosa and ventrolateral tongue.

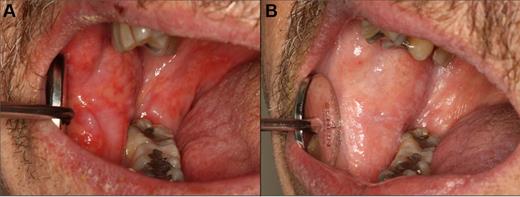

Solutions and gels, which are both hydrophilic and easily applied intraorally, are the mainstays of topical therapy for oral cGVHD. Solutions are generally the easiest to use and most effective for treatment of widespread oral mucosal disease and difficult to access areas, such as the posterior lateral tongue. Only minimal evidence exists to guide the choice in topical corticosteroid therapy for management of oral mucosal cGVHD.36-41 Based on the National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference Ancillary Guidelines and clinical experience, for the majority of patients, we prescribe oral dexamethasone solution (0.5 mg/5 mL) as initial therapy, with the explicit instructions to swish, gargle (if soft palate involved), and spit the solution.33 Reports evaluating topical budesonide solution (3 mg/10 mL) have demonstrated good efficacy;however, results are difficult to compare across studies.38,40,42 The contact time is important; therefore, patients should be encouraged to keep the solution in their mouth for 5 minutes before expectorating. In addition, it is critical to instruct patients not to eat or drink for 10-15 minutes afterward to avoid increasing salivary flow and washing the retained solution off of the mucosal surface. We have patients as young as the age of 4 who are able to follow this regimen without complications, sometimes up to 4 times per day when clinically indicated. In cases of limited oral disease, or where intensive secondary therapy is necessary, high potency (fluocinonide) and ultra-potent (clobetasol) gels can be applied directly to the mucosa. The affected area should first be dabbed dry with gauze; and in cases when it is difficult to isolate saliva, the medication can be placed on a gauze pad, which can be applied directly and left in place for several minutes, or the gel can be mixed with an over-the-counter mucoadhesive base (Orabase, Colgate-Palmolive; mix 1:1 with corticosteroid gel and apply directly to the affected mucosa). The frequency of therapy should be determined largely by symptoms and response. Many patients obtain adequate relief with twice daily treatment, although some may require 4-6 times per day for good control. In the event that these first-line agents are insufficient, or in cases of severe oral cGVHD with extensive painful ulcerations, clobetasol propionate can be compounded into a 0.1-mg/mL solution and used in the same manner, often with rapid results (Figure 13).43 Insurance coverage for compounded medications can vary based on several factors, so in some cases, even if clobetasol solution is not covered, budesonide solution may be and is an excellent alternative.

Management of oral cGVHD with compounded topical clobetasol solution therapy. (A) Extensive ulcerations of the right buccal mucosa. (B) Nearly complete resolution with only residual reticulation and complete symptomatic response after 1 month of intensive topical therapy, with no change in systemic immunosuppression.

Management of oral cGVHD with compounded topical clobetasol solution therapy. (A) Extensive ulcerations of the right buccal mucosa. (B) Nearly complete resolution with only residual reticulation and complete symptomatic response after 1 month of intensive topical therapy, with no change in systemic immunosuppression.

A number of reports have described the effectiveness of topical tacrolimus for management of oral mucosal cGVHD.44-46 Tacrolimus inhibits T-cell activity by blocking IL-2 signaling and, when applied locally, acts directly on the infiltrating cells. Tacrolimus for topical application is only available commercially as an ointment (Protopic 0.1% and 0.03%, Astellas Pharma US; 0.1% should be used for oral cGVHD), which is very difficult to apply intraorally, especially to extensive areas of mucosa. However, the ointment can be applied to well-dried surfaces using one of the application techniques described in the previous paragraph. Tacrolimus ointment is the treatment of choice when the lips are involved as extended use of high potency topical corticosteroids can cause irreversible lip atrophy despite having no long-term mucosal effects. Patients may report some mild burning on application; however, the treatment is typically rapidly effective with notable improvement in appearance and symptoms. Tacrolimus can be compounded as a solution (0.1 mg/mL) and used topically in combination with a corticosteroid solution.41,47 Mawardi et al reported a retrospective case series treated with this combination after inadequate response with dexamethasone rinses alone, with clinical improvement noted.41 At our center, tacrolimus solution is typically added to clobetasol solution as a combined rinse (equal parts) in patients who continue to be symptomatic, even despite substituting clobetasol for dexamethasone solution.48 This combination is generally considered our topical therapy “ceiling” when applied up to 6 times per day. There have been rare reports of clinically significant tacrolimus serum levels developing secondary to topical use; therefore, patients who are already taking systemic tacrolimus should have their levels monitored, and those who are not also being treated with systemic tacrolimus should have serum levels checked within a few weeks after beginning intraoral therapy.49,50

Intralesional corticosteroid therapy is reserved for refractory painful ulcerative cGVHD lesions. We use Kenalog 40 (triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL) and inject ∼ 0.1-0.2 mL/cm2, just below the base of the ulcer. This procedure may need to be repeated on a weekly or every other week basis for several weeks for complete healing. Whenever there is any doubt as to the clinical diagnosis, a biopsy should be obtained.

Cases that are refractory to the aforementioned measures typically require new or increased systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Although a number of other ancillary oral therapies have been described (eg, topical azathioprine and intraoral ultraviolet light phototherapy), there is weak evidence to support the use of any specific intervention.37,51,52 With respect to systemic therapy, in addition to prednisone, extracorporeal photopheresis has consistently demonstrated good efficacy with respect to oral mucosal cGVHD specifically.53

Management of candidiasis

Secondary candidiasis is fairly common and typically develops within the first week of topical steroid therapy. Patients should be informed of the possible signs and symptoms of candidiasis, and all patients should be followed within one month of beginning topical therapy for clinical assessment as fungal infection can exacerbate symptoms and obscure treatment successes. Patients with oral cGVHD are at a significantly increased risk for developing recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis because of underlying immunosuppression (cGVHD and systemic management), use of intensive topical corticosteroid therapy (which suppresses local mucosal immunity), and salivary gland hypofunction. Candidal lesions may present as white patchy pseudomembranes or diffuse erythema, with variable symptoms that include burning and dysgeusia, or in cases of candidiasis secondary to topical therapy for mucosal disease, a worsening of what seems to the patient to be oral cGVHD symptoms (Figure 8). Diagnosis of candidiasis can typically be made clinically, and fungal culture should generally be reserved for cases that do not respond to empiric therapy, to confirm diagnosis and perform antifungal susceptibility testing. A positive culture alone only confirms the presence of Candida albicans in the oral microflora but not a diagnosis of infection. Cytology can be useful for confirming infection, especially in cases of erythematous candidiasis, which can be more difficult to diagnose clinically because of the more subtle findings. Active infections should be treated with a 1-week course of daily fluconazole (100- or 200-mg tablets). We routinely prescribe prophylactic nystatin suspension (5 mL, which can be rinsed at the same time as the topical steroid) and in the absence of systemic drug interactions, at least weekly fluconazole (200-400 mg × 1 dose/wk) to prevent the occurrence or recurrence of candidiasis. Prophylactic or therapeutic fluconazole must be used with caution in patients on systemic immune suppression because of the interaction with calcineurin inhibitors and mTOR inhibitors.

Salivary gland cGVHD

The primary symptom of salivary gland cGVHD is xerostomia, although patients may also describe oral burning and sensitivity. In addition to ensuring good hydration, use of over-the-counter dry mouth products (rinses, sprays, gels) and salivary stimulants (sugar-free gum and candy) can help control symptoms. Because of the increased risk of dental caries, patients must be educated to avoid excessive intake of refined carbohydrates and sugar-containing drinks, and to brush their teeth as frequently as possible after eating. Recurrent candidiasis is a common complication, especially in patients also being treated with topical steroid therapy for concurrent mucosal disease, and should be managed according to the guidelines described under “Management of candidiasis.”

Prescription sialogogue therapy can be effective in reducing xerostomia symptoms (Table 2).15,54-58 Approximately 50% of patients respond with improved salivary flow and decreased xerostomia symptoms; and although full response may take up to 8-12 weeks, improvement is typically noted within 1-2 weeks of beginning therapy. Primarily because of cost considerations, we prescribe pilocarpine (Salagen, 5 mg orally 3 times a day) as initial therapy, reserving cevimeline (Evoxac, 30 mg 3 times a day) for those who do not respond. Both of these agents are US Food and Drug Administration–approved for the management of xerostomia in patients who have received head and neck radiation therapy, but not cGVHD specifically, and appear to have similar rates of efficacy and side effects.15,55,57-59 In the absence of adverse effects, patients should continue to take the medication for at least 8 weeks and the initial dose can be doubled (eg, increasing pilocarpine from 5-10 mg) before making a determination that they are nonresponders.15 Sialogogue therapy is not immunosuppressive but is contraindicated in patients with pulmonary cGVHD (or other obstructive pulmonary disease) because of the potential for stimulation of pulmonary secretions resulting in wheezing and difficulty breathing. Although the primary side effect is excessive sweating, patients with cGVHD rarely report this complication, probably because of associated changes in the skin that diminish sweat gland activity. Of note, patients with cGVHD-associated xerophthalmia may also benefit from this therapy.15,54,58 Systemic immunosuppressive therapy, however, tends to be relatively ineffective in improving symptoms of salivary gland cGVHD.

Superficial mucoceles are generally asymptomatic and do not typically need intervention. When treatment is indicated, topical steroid therapy may reduce the frequency and number of mucoceles. Rarely, symptomatic mucoceles that develop deep in the connective tissue require surgical removal.

Sclerodermatous oral cGVHD

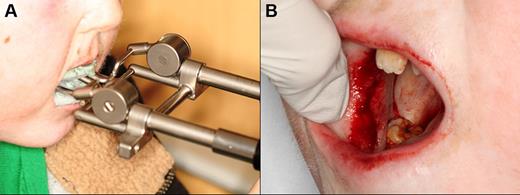

This is an infrequent complication with no published evidence base from which to draw guidance for clinical management. Patients with trismus may benefit from intensive long-term physical therapy with low load passive stretching using one of several commercially available devices (eg, Dynasplint Systems; Figure 14A).60,61 Focal areas of severe fibrosis may benefit from surgical band disruption, resulting in greater range of motion and improved symptoms (Figure 14B). Use of intralesional steroid therapy may also be considered. Localized areas of advanced secondary periodontal recession can be considered for management with connective tissue grafting, although experience is limited and this procedure should be reserved only for severely symptomatic cases.

Eleven-year-old patient with severe trismus secondary to cGVHD-associated mucosal fibrosis. (A) Using the Dynasplint jaw rehabilitation device to improve maximum opening. (B) Undergoing surgical band-release procedure in an attempt to further improve mouth opening.

Eleven-year-old patient with severe trismus secondary to cGVHD-associated mucosal fibrosis. (A) Using the Dynasplint jaw rehabilitation device to improve maximum opening. (B) Undergoing surgical band-release procedure in an attempt to further improve mouth opening.

Long-term complications and surveillance

Patients with a history of oral cGVHD are at risk for a number of late complications, in some cases years after initial diagnosis and management when regular post-transplantation care at specialized centers is no longer occurring (Table 3). In pediatric patients, there can be issues of abnormal tooth and jaw growth and development as a consequence of prior therapy, which can add further complexity to their management.62,63 In addition, children typically report less dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, and taste changes compared with adults.64 It is not known whether the difference in reporting is the result of differences in the manifestations of oral GVHD in adults and children or because issues of cognitive development lead to under-reporting. Because of this, children and their caregivers should be asked specific questions related to oral GVHD symptoms.

Dental caries

Patients with salivary gland cGVHD are at risk for developing secondary infectious complications because of diminished anticariogenic and antifungal activities. The development of accelerated and often rampant dental caries is a largely under-recognized complication of oral cGVHD that can develop rapidly, leading to extensive dental treatment, extraction of teeth, and significant social and economic costs.65-67 Before the development of frank carious lesions, the teeth may demonstrate demineralization changes along the cervical margins, characterized by a white and chalky appearance (Figure 7). Dental caries tend to develop at the cervical margins and interproximal surfaces where dental plaque accumulates because of lack of salivary flow. Exacerbating this problem is that patients with oral mucosal cGVHD may neglect oral hygiene because of discomfort associated with tooth brushing, compounding the effects of salivary gland changes. In addition to the effects on teeth, patients with salivary gland cGVHD are at significant risk for recurrent oral candidiasis, especially if there is ongoing topical corticosteroid therapy.

Prevention of dental caries is a critical component of salivary gland cGVHD management, and we initiate these measures in all patients with clinically significant disease (Table 4). Patients should be continuously reminded of the importance of maintaining a noncariogenic diet and good oral hygiene. In patients with severe salivary gland hypofunction, even when tooth brushing after eating is not feasible, patients should be instructed to rinse their mouths well with water. Prescription 1.1% sodium fluoride gel should be applied to the teeth nightly, either using a toothbrush to “paint on” to the teeth, or via custom-fitting trays that can be fabricated by the patient's dentist.68,69 In addition to topical fluoride, emerging evidence supports the use of a calcium/phosphate-based remineralizing agent (eg, GC MI Paste Plus, GC America), which can be applied just before topical fluoride.70,71 Dentists can place fluoride varnish twice annually during recall visits for further protection. Bitewing radiographs should be obtained on an annual basis to screen for interproximal decay (Figure 15), and areas of decay should be treated promptly and definitively (ie, the full extent of caries must be removed as risk for recurrent decay is high).

Intaoral bitewing radiograph demonstrating multiple interproximal dental caries (radiolucencies) in a patient with salivary gland chronic GVHD.

Intaoral bitewing radiograph demonstrating multiple interproximal dental caries (radiolucencies) in a patient with salivary gland chronic GVHD.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Given the significantly increased risk of developing oral squamous cell carcinoma, all patients with oral cGVHD require periodic screening with a comprehensive extraoral and intraoral examination with a good light source. Patients with a history of Fanconi anemia and dyskeratosis congenita are at significantly increased risk and must be screened regularly, regardless of the development of oral cGVHD.72-75 Patients should be evaluated for submandibular and cervical lymphadenopathy by careful palpation. Intraorally, the mucosa should be inspected for suspicious abnormalities, such as focal masses, atypical appearing plaques, nonhealing deep/necrotic-appearing ulcerations, and induration (Figure 12). The main difficulties in discerning “suspicious” changes from cGVHD-associated changes include the heterogeneous features of oral cGVHD and the fact that mucosal changes can often persist indefinitely, even when apparent cGVHD activity has resolved and patients are asymptomatic. Despite there being a number of commercially available adjunctive agents intended to improve oral cancer screening (eg, toluidine blue vital staining, tissue autofluorescence), none of these has proven benefit over careful examination under adequate white light.76 Areas of suspicious changes require incisional biopsy and histopathologic examination; however, in the absence of obvious clinical findings, there is no known benefit to simply performing serial biopsies for screening purposes. Minimal data exist on treatment outcomes, but it appears that these secondary oral cancers may be associated with higher rates of recurrence and poorer long-term survival compared with de novo squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cancer in non-HCT patients.29

In conclusion, oral cGVHD is a frequent and potentially serious complication after allogeneic HCT. Although not inherently life-threatening, it is associated with significant morbidity because of pain and dysfunction, restricted oral intake, and secondary complications. Given the absence of oral medicine specialists at many transplant centers and the unfamiliarity with transplantation-associated complications in the community, oral cGVHD is probably underdiagnosed and suboptimally managed. With a systematic rational approach to the diagnosis and management of oral cGVHD outlined in this manuscript, symptoms can often be well controlled and complications minimized. In more complicated and refractory cases, however, patients can benefit greatly from referral to an oral medicine specialist. Greater efforts in both educational outreach and clinical research will lead to improved management and better long-term outcomes.

Authorship

Contribution: N.T., C.D., C.C., and L.L. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nathaniel Treister, DMD, DMSc, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Division of Oral Medicine & Dentistry, 1620 Tremont St, 3rd Fl, Boston, MA 02120; e-mail: ntreister@partners.org.