Key Points

HIF-1α protein stabilization increases HSC quiescence in vivo.

HIF-1α protein stabilization increases HSC resistance to irradiation and accelerates recovery.

Abstract

Quiescent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) preferentially reside in poorly perfused niches that may be relatively hypoxic. Most of the cellular effects of hypoxia are mediated by O2-labile hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs). To investigate the effects of hypoxia on HSCs, we blocked O2-dependent HIF-1α degradation in vivo in mice by injecting 2 structurally unrelated prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzyme inhibitors: dimethyloxalyl glycine and FG-4497. Injection of either of these 2 PHD inhibitors stabilized HIF-1α protein expression in the BM. In vivo stabilization of HIF-1α with these PHD inhibitors increased the proportion of phenotypic HSCs and immature hematopoietic progenitor cells in phase G0 of the cell cycle and decreased their proliferation as measured by 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation. This effect was independent of erythropoietin, the expression of which was increased in response to PHD inhibitors. Finally, pretreatment of mice with a HIF-1α stabilizer before severe, sublethal 9.0-Gy irradiation improved blood recovery and enhanced 89-fold HSC survival in the BM of irradiated mice as measured in long-term competitive repopulation assays. The results of the present study demonstrate that the levels of HIF-1α protein can be manipulated pharmacologically in vivo to increase HSC quiescence and recovery from irradiation.

Introduction

To remain in an undifferentiated state, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) need be lodged in specific niches of the BM where they can preserve their essential capacity to self-renew and reconstitute the whole hematopoietic and immune systems on transplantation.1,2 In mice3 and humans,4 the BM contains 2 pools of HSCs: (1) a quiescent pool that divides very infrequently approximately every 145 days to self-renew and maintain a genetic reserve and (2) an activated pool that divides more frequently for the daily replacement of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs), blood leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets. Molecular components of HSC niches are critical to maintaining the correct balance among quiescence, self-renewing proliferation, and differentiation of HSCs. It has been found recently that, in addition to the stromal cells forming niches and the arrays of essential mediators they secrete, the physicochemical conditions within niches are critical to maintaining HSC quiescence and self-renewal.5 For example, the most quiescent HSCs capable of serial reconstitution in serial transplantations reside in niches very poorly perfused by the circulating blood, whereas more active and proliferative HSCs capable of only a single round of transplantation or reconstitution reside in more perfused niches.6 A direct consequence of low perfusion could be increased local hypoxia. Indeed, the oxygenation rate of a tissue is dependent on how rapidly oxygen solubilized in the circulating blood perfuses into the tissue and how rapidly this oxygen is consumed by cells in an active metabolic state.7,8 Similar to the BM, solid tumors are sites of rapid regeneration and cell division. Analyses of blood perfusion and hypoxia in solid tumors have shown that areas that are poorly perfused are stained by the hypoxia sensitive marker pimonidazole, suggesting a hypoxic state,9 and contain tumor stem cells.10,11 Similarly, the endosteal region of the mouse BM, which is known to harbor niches containing quiescent HSCs,3,12-15 is also stained by pimonidazole in steady-state conditions, also suggesting a hypoxic state.16,17

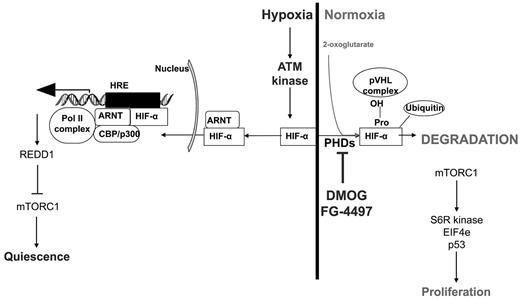

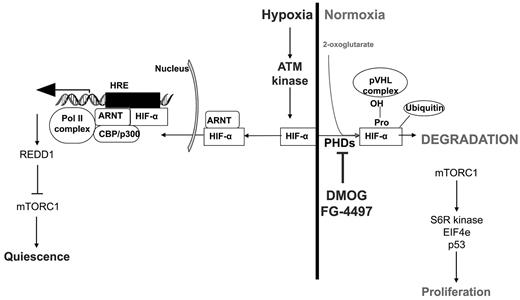

A functional consequence of tissue hypoxia is the stabilization of a family of oxygen-labile transcription factors called hypoxia-inducing factors (HIFs). HIFs are heterodimers of an O2-labile α-subunit, and a stable β-subunit called the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT). Once the HIF-α:ARNT complex is formed, it can then translocate to the nucleus and activate the transcription of genes containing hypoxia-responsive elements. Hematopoietic cells, including HSCs, express HIF-1α mRNA.18 In hypoxic conditions with an oxygen concentration below 2%, the HIF-α protein is stable and the complex with ARNT is formed, translocates to the nucleus, and initiates transcription of hypoxia-responsive element–containing genes. In normoxic conditions or when O2 concentration exceeds 2%, the HIF-1α protein is degraded within 5 minutes of formation by the proteasome,19 preventing the formation of the transcription factor and its translocation to the nucleus (Figure 7). The sensitization of HIF-α proteins to proteasomal degradation in the presence of O2 is mediated by 3 prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes that hydroxylate 2 proline residues within the oxygen degradation domain of HIF-α proteins. These hydroxylated proline residues then bind the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) tumor-suppressor protein to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that ubiquinates and targets HIF-α protein to the proteasome.20 PHD enzymes are Fe(II)–dependent and use 2-oxoglutarate as a substrate to hydroxylate proline residues. They are inactive when O2 is < 2%, resulting in HIF-α protein stabilization.

In the present study, we treated mice with 2 structurally unrelated PHD inhibitors, dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG)21 and FG-4497,22 to determine the effect of pharmacologic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein on HSCs in vivo. We report herein that both agents stabilize HIF-1α protein in vivo in the BM and increase the proportion of HSCs and primitive HPCs into quiescence. As a result, treatment with PHD inhibitors resulted in faster hematopoietic recovery and recovery of higher numbers of transplantable BM HSCs after full-body sublethal irradiation.

Methods

Mouse treatments

All procedures were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the University of Queensland. Seven- to 9-week-old C57BL/6 and 129Sv male mice were injected intraperitoneally daily with 400 mg/kg of DMOG diluted in saline, 20 mg/kg of FG-4497 (at 10 mg/mL in 5% dextrose and 30mM NaOH), or saline. At specified time points, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane before cardiac puncture to harvest blood. Mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation and the BM and bones harvested. In some experiments, mice were injected subcutaneously with 1000 IU/kg of recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO; Eprex 2000; Janssen-Cilag) daily.

Western blotting

For quantification of the HIF-1α protein by Western blotting, C57BL/6 mice were injected with a single dose of 400 mg/kg of DMOG, 20 mg/kg of FG-4497, or saline. BM cells from one femur were flushed at 2, 6, and 12 hours after injection with 1 mL of urea cell lysis buffer (7M urea, 10% glycerol, 1% SDS, 5mM EDTA, and 20mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche) supplemented with 200μM PMSF. These cell lysates were frozen immediately on dry ice and stored at −80°C. For each time point, equal concentrations of protein were mixed with 5× loading buffer containing 10mM dithiothreitol and boiled for 3 minutes. Proteins were separated on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and 5% nonfat powdered milk for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with PBST, membranes were incubated overnight with rabbit anti–mouse HIF-1α Ab (NB100-134; Novus Biologicals) diluted 1/500, and then washed with PBST and incubated with IRD800-conjugated donkey F(ab)′2 fragment anti–rabbit IgG (Rockland Immunochemicals) at a 1/10 000 dilution. For normalization of the results, blots were then probed with a rabbit anti–β-actin loading control Ab (Novus Biologicals). Protein expression was detected and quantified on the Odyssey Infra-Red Imaging System (Li-COR Bioscience) equipped with 2 solid-phase lasers at 700 and 800 nm.23

HIF-1α flow cytometry staining

C57BL/6 mice were injected twice with 20 mg/kg of FG-4497 or saline 12 and 2 hours before euthanasia. After cervical dislocation, one femur was flushed into ice-cold PBS with 2% FCS and 20 mg/mL of FG-4497. BM cells were stained with FITC-lineage antibodies (CD3ϵ, CD5, B220, CD11b, Gr1, CD41, and Ter119), anti–Sca1-PECy7, anti–Kit-PacBlue, CD48-PerCPCy5.5, and CD150-PE (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Washed cells were then fixed using the FIX & PERM kit from Caltag Invitrogen and then permeabilized with 0.05% saponin. Dylight 650-conjugated mouse anti–human HIF-1α (NB 100-134C; Novus Biologicals) was added to the permeabilization buffer at a 1/400 dilution for 30 minutes before washing. Fluorescence was analyzed on a CyAn ADP7c flow cytometer.

BrdU incorporation and cell-cycle analyses

C57BL/6 or 129Sv mice were injected with 400 mg/kg/d of DMOG, 20 mg/kg/d of FG-4497, 1000 IU/kg of EPO, or saline. For the last 3 days of the experiment, mice were administered 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) in the drinking water (0.5 mg/mL). After cervical dislocation, femora, tibiae, pelvic bones, and spines were removed and crushed in a mortar/pestle containing ice-cold PBS with 2% FCS and stained for cell-surface antigens and then for BrdU or Ki67 antigen and DNA content as described previously.24 Briefly, BM leukocytes were enriched for Kit+ cells by MACS using mouse CD117 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). For BrdU staining, enriched Kit+ cells were stained with biotinylated lineage antibodies (CD3ϵ, CD5, B220, CD11b, Gr-1, CD41, and Ter119), anti–Sca1-PECy7, anti–Kit-APC, CD48-PacBlue, and CD150-PE, followed by streptavidin/Alexa Fluor 700 (supplemental Table 1). Cells were washed with PBS, and then fixed and stained for BrdU incorporation using reagents and instructions from the BrdU-FITC flow kit from BD Pharmingen.

For cell-cycle analyses, enriched Kit+ cells were surface stained with biotinylated lineage antibodies, anti–Sca-1-PECY7, anti–KIT-APC, and CD48-PE followed by streptavidin/Alexa Fluor 700 (supplemental Table 1). Washed cells were then fixed and permeabilized using the FIX & PERM kit. FITC-conjugated mouse anti–human Ki67 was added to the permeabilization buffer for 30 minutes. After washing, cells were incubated in 1 mL of PBS containing 1 μg/mL of RNase A, 0.05% saponin, and 20μM Hoechst 33342 for 15 minutes before analysis. Data were acquired on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Colony assays

For myeloid colony assays, 10 μL of whole blood or leukocyte suspension from BM or spleen was deposited in 35-mm Petri dishes and covered with 1 mL of IMDM supplemented with 16% methylcellulose and 35% FCS. Optimal concentrations of mouse IL-3, IL-6, and soluble kit ligand were added as conditioned media from stably transfected BHK cell lines. Colonies were counted after 7 days of culture.

Sublethal irradiation

After treatment with DMOG, FG-4497, or saline, C57BL/6 mice were administered a split dose of 9.0 Gy of irradiation (2 × 4.5 Gy 4 hours apart). Mice were given Bactrim and Diflucan antibiotics in their drinking water for 2 weeks after irradiation. Recovery was monitored by weekly tail bleeds in which blood leukocytes, RBCs, platelets, and hemoglobin levels were measured. Remaining blood was then lysed and stained with CD3ϵ-FITC, B220-APCCy7, CD11b-PECy7, anti–Ly6G-PE, anti–F4/80-Alexa Fluor 647, and anti–Ly6C-PacBlue.

Long-term competitive repopulation transplantations

Our long-term competitive repopulation transplantation protocol has been described previously.25 Briefly, on the day of transplantation, one femur per donor mouse was gently crushed in PBS with 2% FCS with a mortar and pestle. BM cells from all mice within each treatment group were pooled. A total of 200 000 BM cell aliquots were taken from this pool and mixed with 200 000 competitive whole BM cells from untreated congenic B6.SJL CD45.1+ mice in a total volume of 200 μL and injected retroorbitally into each lethally irradiated recipient (11.0 Gy split dose 4 hours apart). Recipients were maintained with antibiotics for the first 3 weeks after transplantation and then tail bled 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation to determine CD45.2 (test donor mobilized BM contribution) versus CD45.1 (competitive BM contribution) expression on myeloid, B-, and T-lineages by flow cytometry.25 Chimerism was considered positive when the contribution of CD45.2+ donor cells was above 0.5% for each blood lineage.

Content in repopulation units (RUs) was calculated for each individual recipient mouse according to CD45.2+ donor blood chimerism at 16 weeks after transplantation using the following formula: RU = D × C/(100 − D), where D is the percentage of donor CD45.2+ B cells and myeloid cells, and C is the number of competing CD45.1+ BM repopulation units. In most cases, C = 2 because 2 × 105 competing BM cells were cotransplanted (a RU is defined as the HSC content in 105 BM cells26 ).

Statistics

Differences were analyzed using a 2-tailed t test or a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test depending on distribution normality. A value of P < .05 was considered significant. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Results

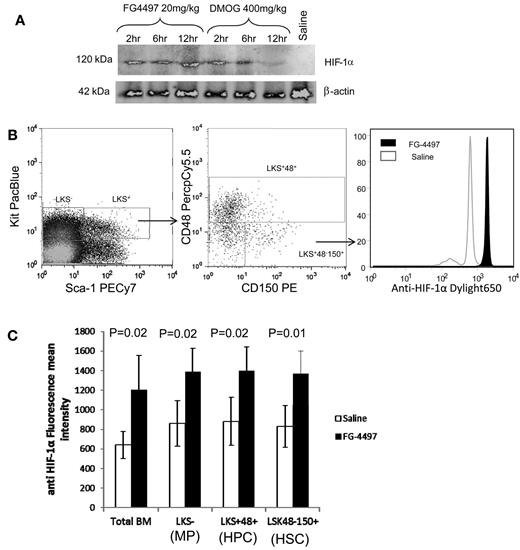

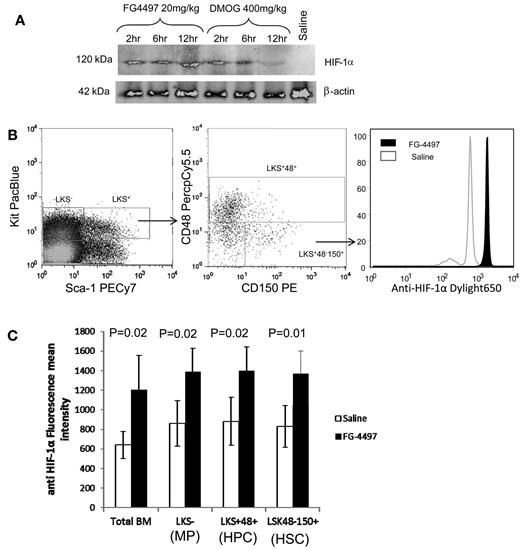

PHD inhibition stabilizes HIF-1α protein in HSCs in the BM

Because HIF-1α mRNA is known to be expressed ubiquitously, we first tested HIF-1α protein expression in mouse BM. The HIF-1α protein was very low in the BM from saline-injected animals (Figure 1A far right lane), which is consistent with our previous findings.16 A single dose of the PHD inhibitor DMOG stabilized HIF-1α protein for up to 6 hours in BM leukocytes before approaching background levels at 12 hours. With a single dose of FG-4497, a more potent and selective PHD inhibitor, HIF-1α protein persisted over 12 hours in BM leukocytes. We next investigated whether treatment with the PHD inhibitor was effective in stabilizing HIF-1α in HSCs, multipotent progenitor cells, and myeloid progenitors. C57BL/6 mice were treated twice with FG-4497 or saline 12 and 2 hours before killing and intracellular HIF-1α protein was measured by flow cytometry (Figure 1B). The geometric mean fluorescence intensity of HIF-1α staining was significantly increased in whole BM leukocytes, Lin−Kit+Sca1− (LKS−) myeloid progenitors, lineage-restricted Lin−Sca1+Kit+ CD48+ (LKS+48+) HPCs, and Lin−Sca1+Kit+CD48−CD150+ (LKS+48-150+) HSCs in FG-4497–treated mice (P < .05; Figure 1C). This suggests that FG-4497 stabilizes in vivo a proportion of cellular HIF-1α protein indiscriminately in all BM leukocytes, including HSPCs.

PHD inhibitors stabilize HIF-1α in vivo. (A) Mice were injected with a single dose of 20 mg/kg of FG-4497, 400 mg/kg of DMOG, or saline and BM cells were harvested at 2, 6, and 12 hours after injection. Cell lysates from 8 × 104 BM cells were run on a SDS-PAGE gel for each time point. After electro-transfer, membrane was blotted with rabbit anti–HIF-1α and anti–β-actin antibodies. (B-C) Mice were injected twice with saline or 20 mg/kg of FG-4497 at 12 and 2 hours prior to harvesting. (B) Typical plots showing the gating strategy to measure intracellular HIF-1α in BM cells. Intracellular HIF-1α protein in HSPC populations was measured by flow cytometry (C). Data are shown as means ± SD (4 mice per group) of the mean fluorescence intensities of HIF-1α fluorescence profiles in total BM leukocytes, LKS+ CD48+ lineage-restricted HPCs, LKS+CD48+CD150− multipotent progenitors, and LKS+CD48−CD150+ HSCs. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

PHD inhibitors stabilize HIF-1α in vivo. (A) Mice were injected with a single dose of 20 mg/kg of FG-4497, 400 mg/kg of DMOG, or saline and BM cells were harvested at 2, 6, and 12 hours after injection. Cell lysates from 8 × 104 BM cells were run on a SDS-PAGE gel for each time point. After electro-transfer, membrane was blotted with rabbit anti–HIF-1α and anti–β-actin antibodies. (B-C) Mice were injected twice with saline or 20 mg/kg of FG-4497 at 12 and 2 hours prior to harvesting. (B) Typical plots showing the gating strategy to measure intracellular HIF-1α in BM cells. Intracellular HIF-1α protein in HSPC populations was measured by flow cytometry (C). Data are shown as means ± SD (4 mice per group) of the mean fluorescence intensities of HIF-1α fluorescence profiles in total BM leukocytes, LKS+ CD48+ lineage-restricted HPCs, LKS+CD48+CD150− multipotent progenitors, and LKS+CD48−CD150+ HSCs. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

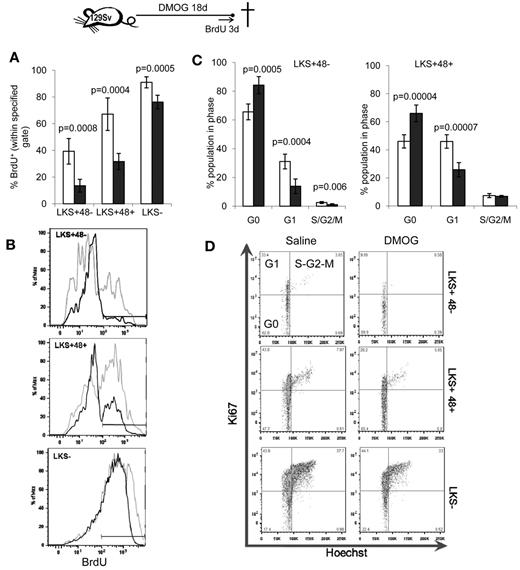

PHD inhibition reduces HSC proliferation

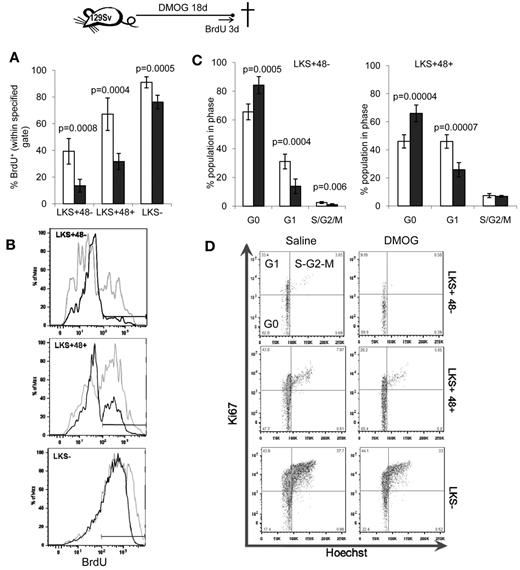

Because dormant HSCs with the highest self-renewal capacity reside in poorly perfused niches and are therefore presumably hypoxic,5,6 we next evaluated the effect of pharmacologic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein with a course of DMOG or FG-4497 on HSC proliferation in vivo. 129Sv mice were administered 400 mg/kg/d of DMOG and HSC proliferation was measured by BrdU incorporation for the last 3 days of the experiment. An 18-day DMOG treatment halved the proportion of LKS+CD48− HSCs and LKS+CD48+ lineage-restricted HPCs that incorporated BrdU (Figure 2A-B). Therefore, a significantly higher proportion of HSPCs did not progress through the S phase during the last 3 days of the experiment. Similarly, cell-cycle analysis showed that DMOG treatment significantly increased the proportion of HSPCs in the G0 phase of the cell cycle (Figure 2C-D), with a reduction of HSCs and HPCs in phase G1.

PHD inhibitors decrease HSPC proliferation in vivo. 129Sv mice were administered DMOG (black columns) or saline (white columns) daily for 18 days. BrdU was administered in the drinking water for the last 3 days of the experiment. (A) Percentage of BrdU+ cells. Data are shown as means ± SD from 5 mice per group. (B) Typical BrdU incorporation flow cytometry profiles for saline-treated (gray) and DMOG-treated (black) mice in LKS+48− HSCs, LKS+48+ and LKS− HPCs. (C) Cell-cycle analysis on LKS+48+ HPCs and LKS+48− HSCs from mice treated with DMOG or saline. (D) Representative dot plots showing the proportion of cells in each phase of the cell cycle after in vivo treatment with saline or DMOG for 18 days. Data in histograms are means ± SD from 5 different mice per group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

PHD inhibitors decrease HSPC proliferation in vivo. 129Sv mice were administered DMOG (black columns) or saline (white columns) daily for 18 days. BrdU was administered in the drinking water for the last 3 days of the experiment. (A) Percentage of BrdU+ cells. Data are shown as means ± SD from 5 mice per group. (B) Typical BrdU incorporation flow cytometry profiles for saline-treated (gray) and DMOG-treated (black) mice in LKS+48− HSCs, LKS+48+ and LKS− HPCs. (C) Cell-cycle analysis on LKS+48+ HPCs and LKS+48− HSCs from mice treated with DMOG or saline. (D) Representative dot plots showing the proportion of cells in each phase of the cell cycle after in vivo treatment with saline or DMOG for 18 days. Data in histograms are means ± SD from 5 different mice per group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

Treatment of C57BL/6 mice with 400 mg/kg/d of DMOG for 18 days also gave similar results, demonstrating that this effect was not strain dependent (supplemental Figure 1). Furthermore, the effect of pharmacologic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein was not limited to LKS+CD48− HSC and LKS+CD48+ HPC phenotypes, because it was also observed in LKS+ Flt3−CD34− HSCs and LKS+ Flt3+ HPCs (supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, pharmacologic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein forces HSCs into quiescence in vivo. Interestingly, the effect of HIF-1α protein stabilization was not restricted to HSCs but was extended to lineage-restricted HPCs. Shorter DMOG treatments (6-12 days) did not alter HSPC cycling or BrdU incorporation (data not shown).

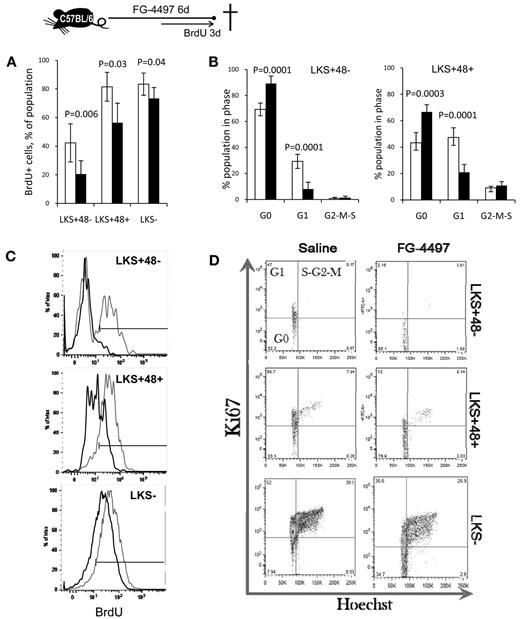

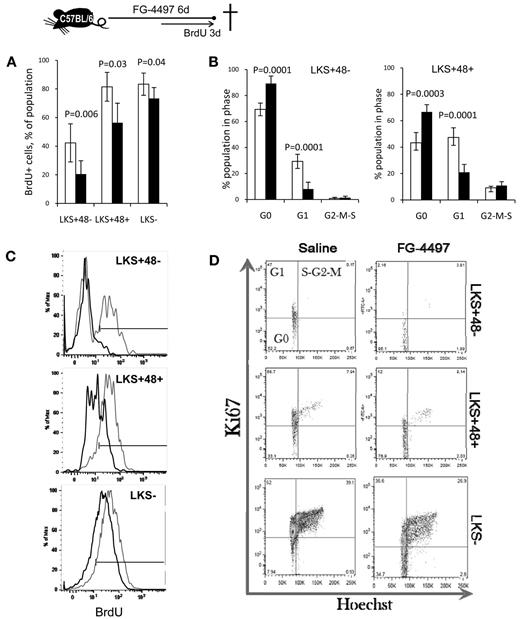

We confirmed the effects of DMOG by treating mice with FG-4497, which significantly decreased BrdU incorporation and significantly increased the proportion of HSPCs in the G0 phase after only 6 days of treatment (Figure 3), likely because of the more lasting effect of FG-4497 on HIF-1α protein stabilization.

FG-4497 decreases HSPC proliferation in vivo. A total of 20 mg/kg of FG-4497 (black bars) or saline (white bars) was administered daily into C57BL/6 mice for 6 days. BrdU was administered in the drinking water for the last 3 days of the experiment. (A) Percentage of BrdU+ cells. Data are show as the means ± SD from 5 mice per group. (C) Typical BrdU incorporation profiles for saline-treated (gray) and FG-4497–treated (black) mice. (B,D) Cell-cycle analysis on LKS+48+ HPCs and LKS+48− HSCs from mice treated with FG-4497 or saline. Representative dot plots showing the proportion of cells in each phase of the cell cycle after in vivo treatment with FG-4497 or saline. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 5 different mice per treatment group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

FG-4497 decreases HSPC proliferation in vivo. A total of 20 mg/kg of FG-4497 (black bars) or saline (white bars) was administered daily into C57BL/6 mice for 6 days. BrdU was administered in the drinking water for the last 3 days of the experiment. (A) Percentage of BrdU+ cells. Data are show as the means ± SD from 5 mice per group. (C) Typical BrdU incorporation profiles for saline-treated (gray) and FG-4497–treated (black) mice. (B,D) Cell-cycle analysis on LKS+48+ HPCs and LKS+48− HSCs from mice treated with FG-4497 or saline. Representative dot plots showing the proportion of cells in each phase of the cell cycle after in vivo treatment with FG-4497 or saline. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 5 different mice per treatment group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

To eliminate the possibility that this effect was not mediated by EPO, the production of which by the kidneys is enhanced in response to these PHD inhibitors,27 we injected a parallel cohort of mice with EPO for 18 days. Despite a strong increase in erythrocytes and hemoglobin concentration in the blood, EPO had no effect on HSPC cycling (supplemental Figure 3).

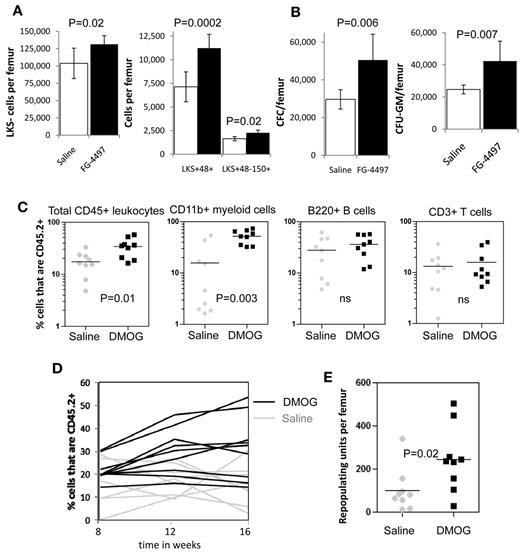

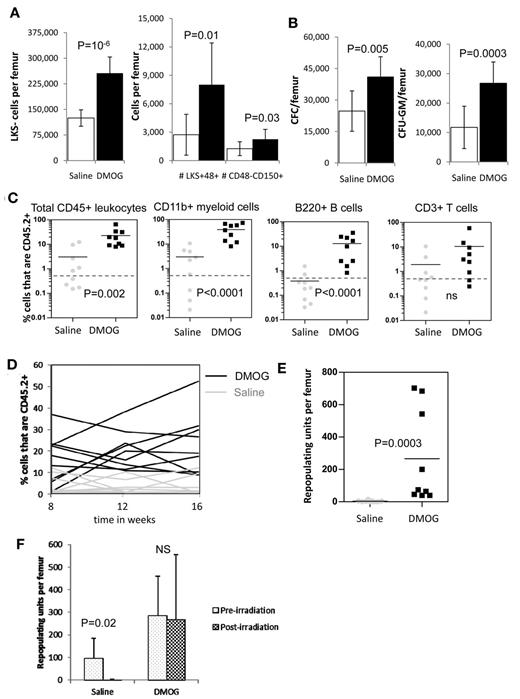

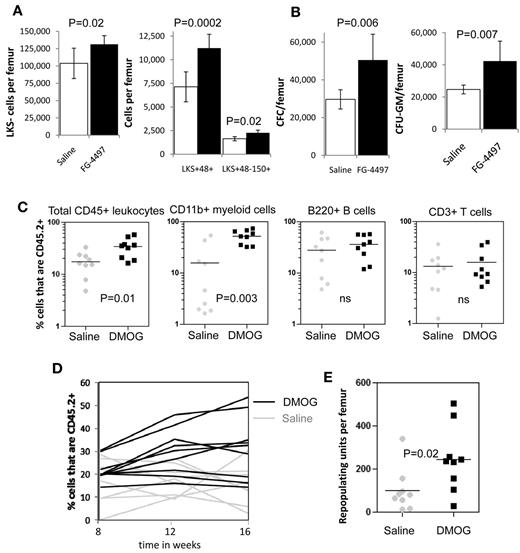

PHD inhibition enhances myeloid potential

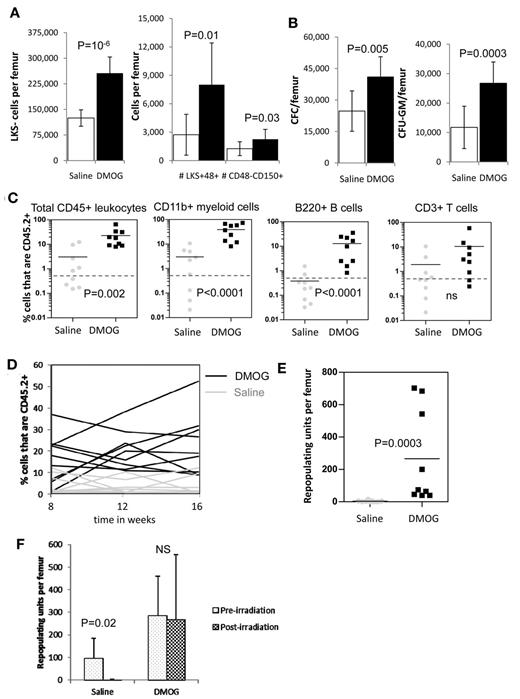

Because PHD inhibition slowed HSC cycling in vivo, we next investigated whether the frequency and number of HSCs and HPCs were altered by PHD inhibitors. We found a significant increase in both the frequency (supplemental Figure 4A) and number of LKS+CD48−CD150+ HSCs (P = .02), lineage-restricted HPCs (LKS+48+; P = .0002), and myeloid progenitors (LKS−; P = .02) after a 6-day treatment with FG-4497 compared with saline (Figure 4A). In addition, we found a significant increase in the number of total CFCs and CFU-GMs (P = .007) per femur when mice were treated with FG-4497 compared with saline (Figure 4B).

In vivo stabilization of HIF-1α increases the number of HSCs and HPCs in the BM. (A) Number of LKS+48-150+ HSCs, LKS+48+ lineage-restricted HPCs, and LKS- myeloid progenitors in mouse BM after a 6-day treatment with saline or FG-4497 in vivo. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 6 mice per treatment group. (B) Number of total CFCs and CFU-GEMM after a 6-day treatment with saline or FG-4497 in vivo. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 6 mice per treatment group. (C) Competitive repopulation assay after treatment with DMOG or saline for 18 days. BM cells from 10 CD45.2+ donor mice per treatment group were pooled within each treatment group. A total of 200 000 CD45.2+ BM cells from each treatment group were transplanted with 200 000 competitive whole BM cells from untreated congenic B6.SJL CD45.1+ mice into 9 lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. CD45.2+ donor contribution was measured in the blood 16 weeks after transplantation in total CD45+ leukocytes, CD11b+ myeloid cells, B220+ B cells, and CD3+ T cells by flow cytometry (all recipients showed multilineage chimerism with over 0.5% donor CD45.2+ contribution in each lineage). Each dot represents an individual recipient; the bar represents the average. (D) Percentage of CD45.2+ donor leukocytes in the blood at 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation. Each line represents an individual mouse (black lines are DMOG-treated donors; gray lines are saline-treated donors). (E) Number of RUs/femur from donor chimerism at 16 weeks after transplantation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 9 mice per group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test (A-B) or Mann-Whitney test (C,E).

In vivo stabilization of HIF-1α increases the number of HSCs and HPCs in the BM. (A) Number of LKS+48-150+ HSCs, LKS+48+ lineage-restricted HPCs, and LKS- myeloid progenitors in mouse BM after a 6-day treatment with saline or FG-4497 in vivo. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 6 mice per treatment group. (B) Number of total CFCs and CFU-GEMM after a 6-day treatment with saline or FG-4497 in vivo. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 6 mice per treatment group. (C) Competitive repopulation assay after treatment with DMOG or saline for 18 days. BM cells from 10 CD45.2+ donor mice per treatment group were pooled within each treatment group. A total of 200 000 CD45.2+ BM cells from each treatment group were transplanted with 200 000 competitive whole BM cells from untreated congenic B6.SJL CD45.1+ mice into 9 lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. CD45.2+ donor contribution was measured in the blood 16 weeks after transplantation in total CD45+ leukocytes, CD11b+ myeloid cells, B220+ B cells, and CD3+ T cells by flow cytometry (all recipients showed multilineage chimerism with over 0.5% donor CD45.2+ contribution in each lineage). Each dot represents an individual recipient; the bar represents the average. (D) Percentage of CD45.2+ donor leukocytes in the blood at 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation. Each line represents an individual mouse (black lines are DMOG-treated donors; gray lines are saline-treated donors). (E) Number of RUs/femur from donor chimerism at 16 weeks after transplantation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 9 mice per group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test (A-B) or Mann-Whitney test (C,E).

We next measured the effect of PHD inhibition on BM reconstitution potential by performing long-term competitive repopulation assays using 2 × 105 BM cells from DMOG-treated mice in competition with 2 × 105 BM cells from untreated congenic CD45.1+ mice. HIF-1α stabilization significantly increased the CD45.2+ donor chimerism after transplantation (Figure 4D) with a 2.5-fold increase in repopulating units per femur at week 16 compared with saline-treated donors (P < .01; Figure 4E). However, this increase in chimerism and RUs/femur was essentially because of higher myeloid reconstitution with the BM from DMOG-treated donors (Figure 4C).

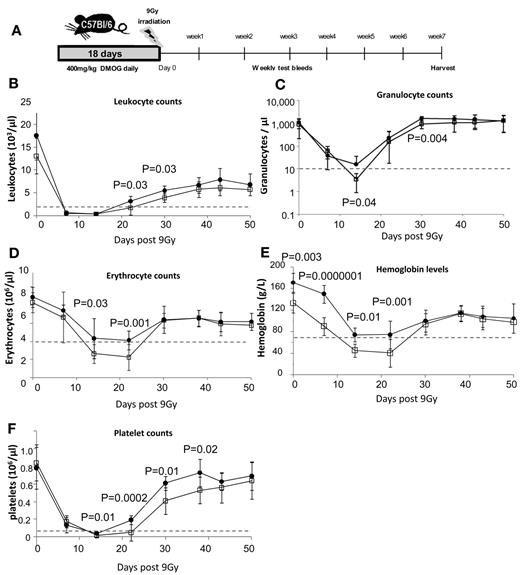

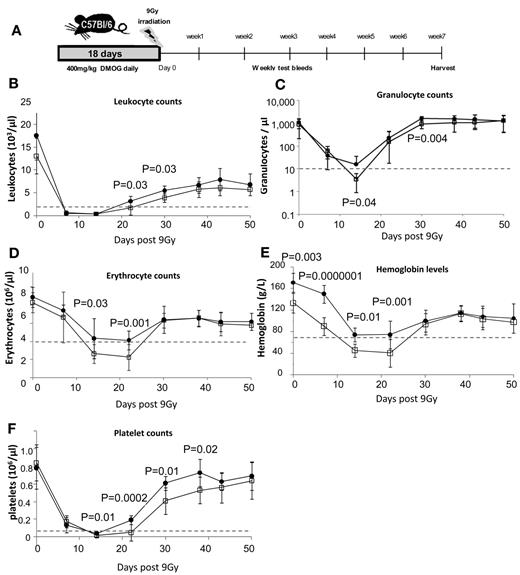

PHD inhibition accelerates blood recovery and protects HSCs after severe irradiation

Because PHD inhibition slows HSPC cycling in vivo, we next investigated whether this could protect HSPCs from severe sublethal irradiation. Mice were treated with 400 mg/kg of DMOG or saline for 18 days and then irradiated with 9.0 Gy (Figure 5A). Both cohorts were leukopenic (< 1500 leukocytes/μL) between days 7 and 14 after irradiation. However, DMOG-treated mice showed significantly accelerated recovery (Figure 5B-F). Using the clinically relevant threshold of < 10 granulocytes/μL blood for severe neutropenia, we found that all (12 of 12) saline-treated control mice became severely neutropenic after irradiation, which was most severe at day 14 (Figure 5C). In contrast, only 1 of the 12 (8%) DMOG-pretreated mice became severely neutropenic at any measured time point after irradiation (P < 10−4 by the Fisher exact statistic).

HIF-1α stabilization enhances blood recovery after severe sublethal irradiation. (A) Timeline of DMOG/saline administration, irradiation, and follow-up during recovery. Time course of blood leukocytes (B), granulocytes (C; measured by flow cytometry on CD11b+ Ly6-G+ cells), erythrocytes (D), hemoglobin (E), and platelets (F) after 9.0 Gy of irradiation of C57BL/6 mice pretreated with saline or DMOG for 18 days. Dashed lines show levels of leukopenia, neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 12 different mice per treatment group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

HIF-1α stabilization enhances blood recovery after severe sublethal irradiation. (A) Timeline of DMOG/saline administration, irradiation, and follow-up during recovery. Time course of blood leukocytes (B), granulocytes (C; measured by flow cytometry on CD11b+ Ly6-G+ cells), erythrocytes (D), hemoglobin (E), and platelets (F) after 9.0 Gy of irradiation of C57BL/6 mice pretreated with saline or DMOG for 18 days. Dashed lines show levels of leukopenia, neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 12 different mice per treatment group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test.

Saline-treated mice also became severely anemic (< 70 g/L of hemoglobin and < 4 × 106 erythrocytes/μL) between days 14 and 22 after irradiation, whereas DMOG-treated mice showed only moderate anemia (70-100 g/L of hemoglobin; Figure 5D-E). Finally, saline-treated mice were thrombocytopenic (< 20 platelets/μL) between days 14 and 21, whereas DMOG-treated mice showed significantly faster platelet recovery and shorter thrombocytopenia (Figure 5F).

By day 50, mice from both groups had recovered to pre-irradiation levels of RBCs, hemoglobin, granulocytes, and platelets. To investigate whether DMOG pretreatment also promoted long-term HSC survival or the ability to recover, BM was harvested from these mice 50 days after irradiation. We found that DMOG treatment induced a significant 2-fold increase in the frequencies (supplemental Figure 4B) and numbers of phenotypic HSCs, HPCs, and myeloid progenitors compared with control mice (Figure 6A) and a significant 2-fold increase in the number of CFCs and CFU-GMs per femur (Figure 6B).

HSPC radiation resistance increased by HIF-1α protein stabilization in vivo. Mice were treated with saline or DMOG for 18 days, irradiated with 9.0 Gy, and the BM harvested 7 weeks later (see timeline in Figure 5A). Shown are the numbers of LKS+48− HSCs, LKS+48+ lineage-restricted HPCs, and LKS− myeloid progenitors (A) and total CFCs and CFU-GMs (B) in mouse BM 50 days after 9.0 Gy of irradiation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 6 mice per group. (C) Competitive repopulation assay at day 36 (week 5) after 9.0Gy irradiation following a pre-treatment with DMOG or saline for 18 days (see timeline in Figure 5A). BM cells from 10 CD45.2+ donor mice per treatment group were pooled within each treatment group. A total of 200 000 CD45.2+ BM cells from each treatment group were transplanted with 200 000 competitive whole BM cells from untreated congenic B6.SJL CD45.1+ mice into 9 lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. (C) Percentages of CD45.2+ donor contribution in total CD45+ leukocytes, CD11b+ myeloid cells, B220+ B cells, and CD3+ T cells 16 weeks after transplantation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 9 mice per group. Each symbol represents an individual recipient mouse, bars are averages, dotted lines represent the 0.5% CD45.2+ threshold above which chimerism was considered to be positive. (D) Percentage of CD45.2+ donor leukocytes in the blood at 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation. Each line represents an individual mouse (black lines are DMOG-treated donors; gray lines are saline-treated donors). (E) Number of RUs/femur from donor chimerism at 16 weeks after transplantation. (F) Comparison of RUs/femur in mice treated with DMOG or saline before (Figure 4C) and 50 days after (Figure 6C) 9.0 Gy of irradiation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 9 mice per group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test (A-B) or a Mann-Whitney test (C,E,F). NS indicates not significant.

HSPC radiation resistance increased by HIF-1α protein stabilization in vivo. Mice were treated with saline or DMOG for 18 days, irradiated with 9.0 Gy, and the BM harvested 7 weeks later (see timeline in Figure 5A). Shown are the numbers of LKS+48− HSCs, LKS+48+ lineage-restricted HPCs, and LKS− myeloid progenitors (A) and total CFCs and CFU-GMs (B) in mouse BM 50 days after 9.0 Gy of irradiation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 6 mice per group. (C) Competitive repopulation assay at day 36 (week 5) after 9.0Gy irradiation following a pre-treatment with DMOG or saline for 18 days (see timeline in Figure 5A). BM cells from 10 CD45.2+ donor mice per treatment group were pooled within each treatment group. A total of 200 000 CD45.2+ BM cells from each treatment group were transplanted with 200 000 competitive whole BM cells from untreated congenic B6.SJL CD45.1+ mice into 9 lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. (C) Percentages of CD45.2+ donor contribution in total CD45+ leukocytes, CD11b+ myeloid cells, B220+ B cells, and CD3+ T cells 16 weeks after transplantation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 9 mice per group. Each symbol represents an individual recipient mouse, bars are averages, dotted lines represent the 0.5% CD45.2+ threshold above which chimerism was considered to be positive. (D) Percentage of CD45.2+ donor leukocytes in the blood at 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation. Each line represents an individual mouse (black lines are DMOG-treated donors; gray lines are saline-treated donors). (E) Number of RUs/femur from donor chimerism at 16 weeks after transplantation. (F) Comparison of RUs/femur in mice treated with DMOG or saline before (Figure 4C) and 50 days after (Figure 6C) 9.0 Gy of irradiation. Data are shown as the means ± SD from 9 mice per group. Significance levels were calculated using a t test (A-B) or a Mann-Whitney test (C,E,F). NS indicates not significant.

This increase in the number of phenotypic HSCs after treatment with a PHD inhibitor was confirmed in a repeat experiment in which we performed long-term competitive repopulation assays with BM cells. HIF-1α stabilization induced by the administration of DMOG before irradiation increased long-term competitive repopulation potential of the BM from irradiated mice (Figure 6D), with a significant increase in myeloid and B-cell repopulation potentials at 16 weeks after transplantation (Figure 6C). Indeed, although only 2 of 9 recipients of irradiated CD45.2+ BM from the saline-treated group had multilineage chimerism (above 0.5% in myeloid, B-, and T-lineages), multilineage chimerism increased to 7 of 9 recipients when irradiated BM from the DMOG-treated group was transplanted (P = .03 by Fisher exact test). Based on chimerism 16 weeks after transplantation, the number of RUs/femur in irradiated mice pretreated with DMOG was 89-fold higher compared with irradiated mice pretreated with saline (Figure 6E). Plots of RUs/femur in DMOG- and saline-pretreated mice before and after irradiation showed that whereas the number of RUs/femur was reduced 27-fold in the saline-treated group 50 days after irradiation, irradiation did not decrease the number of RUs/femur in DMOG-pretreated mice (Figure 6F). These results suggest that pretreatment with DMOG enhanced HSPC survival to severe sublethal irradiation, enabling faster recovery of the irradiation-induced neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia and maintenance of functional HSCs within the irradiated BM.

Discussion

This is the first report on the in vivo effects of pharmacologic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein on hematopoiesis in wild-type mice. Two structurally unrelated PHD inhibitors, DMOG and FG-9947, efficiently stabilized the HIF-1α protein in the BM independently of O2 concentration. HIF-1α stabilization occurred in all BM leukocytes, including HPCs and HSCs. This resulted in a significantly higher proportion of HSCs and multipotent HPCs in quiescence, leading to decreased HSPC proliferation. This effect was not mediated by EPO, the production of which by the kidneys is enhanced in response to these PHD inhibitors.27 In vivo treatment with PHD inhibitors also increased myeloid reconstitution of transplanted BM cells. Finally, pharmacologic stabilization of HIF-1α protein before severe 9.0-Gy sublethal irradiation enhanced recovery from irradiation-induced leucopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia, resulting in an 89-fold higher recovery of RUs/femur.

Our results show that treatment with DMOG in steady-state conditions enhanced myeloid reconstitution of the BM in a long-term competitive repopulation transplantation assay and increased both the numbers and frequencies of phenotypic myeloid progenitors and HSPCs. However, because we did not perform transplantations with serial dilutions of BM cells, we cannot confirm whether the number of actual reconstituting HSCs was increased by DMOG treatment alone despite the increase in frequency and number of phenotypic LKS+CD48−CD150+ cells in the BM of DMOG-treated mice. Nevertheless, DMOG pretreatment before 9.0 Gy of irradiation very clearly protected HSCs from irradiation, with multilineage reconstitution potential of the irradiated BM increasing to levels comparable to multilineage reconstitution of naïve, nonirradiated BM. This result clearly suggests that DMOG pretreatment protects long-term reconstituting HSCs from severe sublethal irradiation.

Because PHD inhibitors stabilized the HIF-1α protein in all BM cells in vivo, including HSPCs, our data do not distinguish whether their effect on HSPC cycling is HSPC intrinsic or if it is indirectly mediated by the microenvironment. However, conditional deletion of the Hif1a gene in hematopoietic cells18 or the effect of hypoxia and PHD inhibitors on cultures of sorted HSPCs28 suggest that the in vivo effect of PHD inhibitors may be intrinsic to HSPCs. Indeed, sorted LKS+Flt3−CD34− HSCs cultured in hypoxic conditions accumulate in phase G0 because of the accumulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21cip, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2 in response to HIF-1α protein stabilization28 and reduced mitochondrial oxidative glycolysis.29 This is also consistent with the decreased proportion of LKS+CD34− HSCs in phase G0 observed in vivo after inducible deletion of the Hif1a gene in hematopoietic cells and, conversely, the increased proportion of HSCs in G0 after conditional deletion of the Vhl gene, which promotes the proteasomal degradation of HIF-α proteins when O2 > 2%.18 The HSC-autonomous mechanisms by which hypoxia and HIF-1α increase HSPC quiescence may involve reduction of mitochondrial activity, metabolic switch from mitochondrial oxidative glycolysis to anaerobic glycolysis, reduced neogenesis of amino acids and nucleotides from products of the tricarboxylic cycle, and inhibition of the Akt/mTOR/S6 phosphorylation pathways.29

Interestingly, the effect of stabilized HIF-1α protein on cycling and proliferation was not restricted to HSCs, but was extended to lineage-restricted LKS+ CD48+ HPCs and, to a lesser extent, to myeloid progenitors. This is consistent with our observation that pretreatment with DMOG lessens the impact of severe sublethal irradiation on leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets and increases the survival of HSPCs in the BM. Indeed, cells in phase G0 are more radiation resistant, with radiation sensitivity peaking in late phase G2/M.30 These data are also consistent with reports that malignant cells cultured in hypoxic conditions become more resistant to radiation.31 In our experiments, stabilization of the HIF-1α protein in vivo was sufficient to increase HSPC radiation resistance. How hypoxia increases radioresistance is not fully understood. Enhanced hypoxia may reduce the production of deleterious reactive oxygen species that could further damage DNA during irradiation.31 Conversely, hypoxia has been reported to activate the p53-dependent growth arrest and survival pathway by attenuating p53 phosphorylation in a human colorectal carcinoma cell line.32 Whether such a mechanism takes place in HSPCs in response to hypoxia or PHD inhibitors remains to be determined. Hypoxia and HIF-1α may also affect directly the activity of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) pathway, which plays a critical role in DNA repair in HSCs during aging33 or after ionizing radiation.34,35 Indeed, HIF-1α is rapidly degraded even in hypoxic conditions in cells with defective ATM kinase,36 suggesting that ATM is another critical regulator of HIF-1α protein stability. Reciprocally, hypoxia activates ATM protein kinase by DNA damage–independent mechanisms.37,38 Hypoxia-activated ATM kinase serine-phosphorylates HIF-1α protein, which stabilizes HIF-1α37,38 and suppresses the catalytic activity of mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1 (mTORC1).37,38 Although it remains to be demonstrated, it may be that PDH inhibitors also activate ATM kinase via HIF-1α stabilization and subsequently attenuate p53 phosphorylation and mTORC1 activity in HSPCs (Figure 7). This would enhance DNA repair and reduce proliferation by inhibiting activities of the mTORC1 targets S6 ribosomal protein kinase and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E.

Regulation of the HIF-1α protein under hypoxic and normoxic conditions, the effect of PHD inhibitors on HIF-1α stabilization, and possible effects on HSC quiescence/proliferation via the ATM kinase and mTORC pathways. S6R kinase indicates S6 ribosomal protein kinase; EIF4e, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; HRE, hypoxia-responsive element; REDD1, regulated in development and DNA response 1.

Regulation of the HIF-1α protein under hypoxic and normoxic conditions, the effect of PHD inhibitors on HIF-1α stabilization, and possible effects on HSC quiescence/proliferation via the ATM kinase and mTORC pathways. S6R kinase indicates S6 ribosomal protein kinase; EIF4e, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; HRE, hypoxia-responsive element; REDD1, regulated in development and DNA response 1.

Finally, because Kit ligand expressed by endothelial cells in vascular niches is critical to HSC survival and maintenance in the BM,39 our results must also be interpreted in the context of the vascular niche. The perfusion of vascular HSC niches is likely to be heterogeneous. BM sinusoids are flaccid without basal lamina and sinusoidal blood flow is rhythmic, with a filling period of 1-2 minutes (during which blood flow slows and stops) followed by a shorter emptying phase.40 Consequently, corpuscular blood velocity is low (0 to 0.2 mm/s) in these sinusoids, whereas it is 0.5-1.0 mm/s in capillaries feeding sinusoids in nutrients and oxygen and 1.5 mm/s in more distant arterioles.40 Therefore, sinusoids more distant from arterioles could be more poorly perfused than sinusoids more proximal to arterioles. Consequently, hypoxia (which is inversely proportional to perfusion) and HIF-1α stabilization could be heterogeneous among BM vascular niches. In this scenario, pharmacologic HIF-1α stabilization in HSCs located in more perfused vascular niches could explain the increased proportion of quiescent and radioresistant HSCs.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that PHD and HIF-1α play a critical role in regulating HSPC quiescence in vivo and that levels of the HIF-1α protein can be pharmacologically manipulated with PHD inhibitors to increase HSPC quiescence in vivo. We conclude that the administration of PHD inhibitors may represent pharmacologic tools to reduce HSPC proliferation and increase HSC radiation resistance in vivo.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by project grant 604303 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. I.G.W. is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (488817 and APP1033736). During the course of this study, J.P.L. was supported by a Senior Research Fellowship from the Cancer Council of Queensland.

Authorship

Contribution: C.E.F. planned and performed the experiments, interpreted the results, and wrote and edited the manuscript; I.G.W. planned and performed the experiments, interpreted the results, and edited the manuscript; B.N. and V.B. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; G.W. helped design the experiments with FG-4497, provided background information, and edited the manuscript; and J.-P.L. conceived and coordinated the study, planned and performed the experiments, interpreted the results, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.W. is an employee of and owns equity in FibroGen Inc, which owns the commercial rights to FG-4497. FibroGen did not provide any funding for this work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jean-Pierre Levesque, Mater Medical Research Institute, Level 4, 37 Kent Street, Woolloongabba 4102, Australia; e-mail: jplevesque@mmri.mater.org.au.