Key Points

Additional genetic aberrations apart from KIT D816V are found in advanced systemic mastocytosis.

Additional genetic aberrations apart from KIT D816V are associated with a significant reduction of overall survival.

Abstract

To explore mechanisms contributing to the clinical heterogeneity of systemic mastocytosis (SM) and to suboptimal responses to diverse therapies, we analyzed 39 KIT D816V mutated patients with indolent SM (n = 10), smoldering SM (n = 2), SM with associated clonal hematologic nonmast cell lineage disorder (SM-AHNMD, n = 5), and aggressive SM (n = 15) or mast cell leukemia (n = 7) with (n = 18) or without (n = 4) AHNMD for additional molecular aberrations. We applied next-generation sequencing to investigate ASXL1, CBL, IDH1/2, JAK2, KRAS, MLL-PTD, NPM1, NRAS, TP53, SRSF2, SF3B1, SETBP1, U2AF1 at mutational hotspot regions, and analyzed complete coding regions of EZH2, ETV6, RUNX1, and TET2. We identified additional molecular aberrations in 24/27 (89%) patients with advanced SM (SM-AHNMD, 5/5; aggressive SM/mast cell leukemia, 19/22) whereas only 3/12 (25%) indolent SM/smoldering SM patients carried one additional mutation each (U2AF1, SETBP1, CBL) (P < .001). Most frequently affected genes were TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, CBL, and RUNX1. In advanced SM, 21/27 patients (78%) carried ≥3 mutations, and 11/27 patients (41%) exhibited ≥5 mutations. Overall survival was significantly shorter in patients with additional aberrations as compared to those with KIT D816V only (P = .019). We conclude that biology and prognosis in SM are related to the pattern of mutated genes that are acquired during disease evolution.

Introduction

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a rare hematologic neoplasm characterized by abnormal accumulation of mast cells in various tissues, predominantly skin, bone marrow (BM), and visceral organs.1,2 The phenotype and extent of organ infiltration/dysfunction are categorized into B- and C-findings, which are the basis for the subclassification of SM into indolent SM (ISM), smoldering SM (SSM), SM with associated hematologic nonmast cell disease (SM-AHNMD), aggressive SM (ASM), and mast cell leukemia (MCL).3-5 Somatic point mutations in the kinase domain of the receptor tyrosine kinase (TK) KIT at position 816 (D816V >95%; D816H, D816Y, and others <5%) play a central role in the pathogenesis and diagnosis of SM.6 Depending on subtype of SM, material (BM or peripheral blood [PB]), and assay sensitivity, the KIT D816V mutation is detectable in ≥90% of SM patients.7 In addition, it was recently shown that multilineage involvement by KIT D816V has an important impact on phenotype and prognosis.8

The vast majority of adult patients are diagnosed with ISM, which is considered to be compatible with a normal lifespan.9 In contrast, patients with advanced SM (SM-AHNMD, ASM and MCL) have a significantly inferior prognosis.4 Treatment options in ISM range between watchful waiting, treatment of symptoms, and prophylactic use of antimediator-type drugs. Cytoreductive therapy and treatment with targeted drugs is usually restricted to patients with advanced SM. In vitro data and murine models suggested major growth-inhibitory effects of TK inhibitors (TKIs), eg, nilotinib, dasatinib, or midostaurin (PKC412), on neoplastic mast cells exhibiting KIT D816V.10-12 With the exception of midostaurin, however, phase-1/2 studies showed disappointingly poor response rates.4,13 Moreover, not all patients respond to midostaurin, and many relapse after having entered remission.14 The reasons for the discrepancies between the efficacy of KIT inhibitors in vitro and in vivo are unclear, but one possibility might be the presence of additional, as yet unknown, molecular aberrations that influence response.15,16 Indeed, it has been described that neoplastic mast cells in advanced SM can expand independent of KIT D816V.17

Here we report on the identification of additional molecular aberrations in a cohort of 39 KIT D816V positive SM patients. Patients with advanced SM more frequently exhibited mutations in genes other than KIT compared with patients with ISM. The most commonly involved genes were TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and CBL. In addition to the multilineage involvement by KIT D816V, the presence of additional molecular aberrations is a new molecular feature that may contribute essentially to the abnormal phenotype and behavior of neoplastic MC in advanced SM and thus to the clinical diversity and prognosis of advanced mast cell disorders.

Material and methods

Diagnosis and subclassification of SM

According to the World Health Organization classification,1,2 diagnosis of SM was based on histology and immunohistochemistry (tryptase, CD117, CD2, CD25) of BM biopsies that were evaluated by reference pathologists of the “European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM)” (H.-P.H., K.S.). Diagnosis of SM needed the presence of one major (multifocal dense infiltrates of mast cells in BM biopsies and/or in sections of other extracutaneous organs) and at least one minor or presence of three minor criteria (>25% atypical cells on BM smears or spindle-shaped mast cell infiltrates, KIT D816V point mutation in BM or other extracutaneous organs, expression of CD2 and/or CD25 by mast cells in BM, PB, or another extracutaneous organ, and baseline serum tryptase concentration >20 μg/L).2,18 Diagnosis of ASM and MCL was based on the presence of one or more C-findings (cytopenia [absolute neutrophil count <1 × 10e9/L, hemoglobin <10.0 g/dL, or platelets <100 × 10e9/L], hepatomegaly with impaired liver function, palpable splenomegaly with signs of hypersplenism, malabsorption with significant hypoalbuminemia and/or significant weight loss >10% throughout the previous 6 months).2,3 Following the recommendations of international expert panels and current trial protocols, pathological fractures resulting from osteoporosis alone did not qualify for diagnosis of ASM. Diagnosis of SSM was based on the presence of 2/3 diagnostic B-findings (hepato-/splenomegaly, BM mast cells >30%, serum tryptase >200 µg/L) in the absence of C-findings. In SM-AHNMD, BM morphology and blood counts showed an associated hematologic nonmast cell lineage neoplasm that most frequently included a myeloid neoplasm, eg, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (SM-CMML), myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm unclasssified (SM-MDS/MPNu), hypereosinophilic syndrome/chronic eosinophilic leukemia (SM-HES/CEL), or acute myeloid leukemia (SM-AML).3,4,19

Patients’ characteristics

We analyzed PB (n = 32) and BM (n = 9) samples from 39 KIT D816V positive SM patients (male, n = 22; female, n = 17, median age 65 years, range 39-80). Frequencies of SM subtypes were distributed as follows: ISM, n = 10; SSM, n = 2; ISM-AHNMD, n = 5 (CMML, n = 2; MDS/MPNu, n = 3); ASM, n = 1; ASM-AHNMD, n = 14 (CMML, n = 5, MDS/MPNu, n = 4, HES/CEL, n = 2; AML, n = 3); MCL, n = 3; MCL-AHNMD n = 4 (MDS/MPNu, n = 2; HES/CEL, n = 1; MDS, n = 1). FIP1L1-PDGFRA and alternative rearrangements of PDGFRA or PDGFRB were excluded by RT-PCR, FISH, and cytogenetics (no rearrangement of 4q12 and 5q31-33) in all 3 patients with significant eosinophila. Patient characteristics are listed in supplemental Table 1. All patients provided informed consent. The study design adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the relevant institutional review board as part of the “German Registry on Disorders of Eosinophils and Mast Cells.”

Mutation analysis

Next-Generation Deep Amplicon Sequencing by 454 FLX amplicon chemistry (Roche, Penzberg, Germany)20 was used to investigate the following candidate genes at known mutational hotspot regions: KIT (exon 17), CBL (exons 8 and 9), IDH1 (codonR132), IDH2 (codons R140 and R172), KRAS (exons 2 and 3), U2AF1 (p.Ser34 and pGln154), SRSF2 (exon 1), SF3B1 (exons 11-16), SETBP1 (codons 800-935), and TP53 (exons 3-9). Additionally, complete coding regions were analyzed for TET2, EZH2, ETV6, and RUNX1 (β isoform). Sanger Sequencing analyzed exon 12 of ASXL1. Mutational hotspots in JAK2 (exons 12 and 14) and NRAS (exons 2 and 3) were analyzed by melting curve analysis with subsequent Sanger sequencing. Screening of NPM1, IDH1/2, and analysis for MLL-PTD was performed as described previously.21-23 For each of the 39 patients, in total 74 amplicons were processed. The corresponding primer sequences and amplification protocols were previously published.20,24-30 Next-Generation Deep Amplicon Sequencing analysis was performed with at least 200-fold coverage (mean: 698, range: 200-872) allowing detection of a minimal mutation burden of 1% to 2%. Read depth was defined as the total number of reads at that position. The same sensitivity was obtained by melting curve analysis. Sanger sequencing for ASXL1 showed a sensitivity of 10%. Known polymorphisms were identified from publicly available data (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP) and removed from the analysis. Constitutional DNA was not available for most cases but all mutations have been identified previously as somatic events or were likely causal in nature (truncating or splice site mutations) except for ETV6 H308Y, which was seen in one case. This change was confirmed as somatic by sequencing DNA obtained from a buccal swab.

Mutation analysis in microdissected cells

Statistical analysis

Correlation between variables was investigated by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and scatter plots, Mann-Whitney U test (t-approximation), or Fisher’s exact test, whichever was appropriate. Survival probabilities and median times were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The significance level of the two-sided P values was .05 for all statistical testing procedures. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2.

Results

Frequency and distribution of molecular aberrations

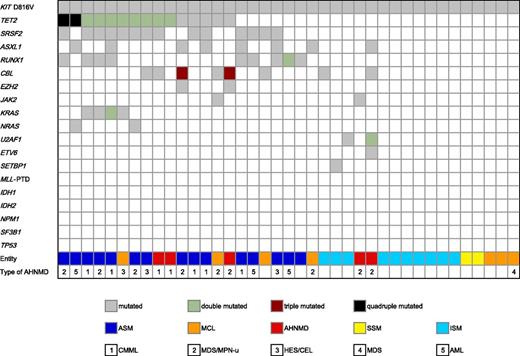

In all patients, the KIT D816V (n = 39) mutation was detected in BM. In 31 patients, the KIT D816V mutation was also found in PB, whereas in 8 patients, no KIT D816V mutation was detectable in PB (ISM, n = 7; ASM, n = 1). In addition to KIT D816V, 86 point mutations or insertions/deletions/duplications in 21 genes were identified in 27/39 (69%) patients (Figure 1). The five most frequently affected genes were TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and CBL. In TET2, 9 missense, 4 nonsense, 13 frameshift mutations and one in-frame deletion, as well as one splice site mutation were identified in 15/39 (39%) patients. Ten of 15 (67%) patients carried more than one TET2 mutation. In SRSF2, missense mutations were identified in 14/39 (36%) patients, which were clustered at codon 95 (p.Pro95His, n = 9; p.Pro95Leu, n = 2; p.Pro95Arg, n = 2), with one additional mutation identified at codon 18 (p.Val18Leu, n = 1). In RUNX1, 10 mutations (9 missense mutations, 1 frameshift) were identified in 9/39 (23%) patients. Twelve CBL mutations were identified in 8 patients (10 missense mutations, 1 duplication, 1 splice mutation). Eight ASXL1 mutations were identified in 8 patients (7 frameshift and 1 nonsense mutation). In 13 patients, two (TET2, n = 8; KRAS, n = 1), three (CBL, n = 2) or four mutations (TET2, n = 2) were found in a single gene.

Alignment of gene mutations and phenotype. Each column represents one of the 39 analyzed samples. The clinical diagnoses are shown in different colors, and the numbers specify the type of AHNMD. Results of analyses of 18 investigated genes are depicted in white (wild-type), gray (single-mutated), green (double mutated), red (triple mutated), and black (quadruple mutated).

Alignment of gene mutations and phenotype. Each column represents one of the 39 analyzed samples. The clinical diagnoses are shown in different colors, and the numbers specify the type of AHNMD. Results of analyses of 18 investigated genes are depicted in white (wild-type), gray (single-mutated), green (double mutated), red (triple mutated), and black (quadruple mutated).

Less frequently affected genes were KRAS, NRAS, JAK2, U2AF1, EZH2, and ETV6. In KRAS, 5 missense mutations were detected in 4 patients, whereas NRAS (1 missense mutation in codon 12 and 1 missense mutation in codon 61) and JAK2 V617F mutations were present in 2 patients, respectively. In U2AF1, 3 missense mutations were found in 2 patients. A missense mutation and 2 splice site mutations were detected in EZH2, and 1 mutation was found in SETBP1 and ETV6, respectively. No mutations were identified in 6 genes (MLL, IDH1, IDH2, NPM1, SF3B1, TP53). Mutation distributions and frequencies in the diverse subtypes of SM are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Association between mutational profiling and subtype of SM

Overall, additional mutations/deletions were identified in 24/27 (89%) patients with advanced SM (SM-AHNMD, 5/5, 100%; ASM/MCL, 19/22, 86% [ASM, n = 1; ASM-CMML, n = 5; ASM-MDS/MPN, n = 4; ASM-HES/CEL, n = 2; ASM-AML, n = 3; MCL, n = 1; MCL-HES/CEL, n = 1; MCL-MDS/MPN-u, n = 2]) whereas only 3/12 (25%) ISM/SSM patients carried an additional mutation (Fisher test P < .001; mutations in Figure 1). In advanced SM, 21/27 (78%) patients carried ≥3 mutations and 11/27 (41%) patients had ≥5 mutations. The median number of mutations was 4. The concurrent presence of KIT-TET2-SRSF2 (10/39, 26%), KIT-SRSF2-RUNX1 (7/39, 18%), KIT-TET2-CBL (5/39, 13%), KIT-SRSF2-ASXL1 (4/39, 10%), and KIT-TET2-ASXL1 (4/39, 10%) was strongly associated with (A)SM/MCL-AHNMD in 16/16 (100%) of patients (CMML, 7/16, 44%; MDS/MPNu, 6/16, 38%; HES/CEL, 3/16, 19%) (Figure 1). The mutational loads are presented in supplemental Table 1. Mutations in CBL and KRAS or RUNX1 and JAK2 were not seen concomitantly in the same patient.

Further associations

Patients with additional mutations were significantly older than patients with just the KIT D816V mutation (P = .013; median age: 68 years vs 48 years). Age was also significantly different between the subtypes of SM (P = .002). Median age of the 12 patients with ISM/SSM was 48 and of the patients with advanced SM 70 years. There was no difference in the number of mutations regarding gender.

Correlation between mutational profiles and clinical behavior in SM

Strikingly, 23/24 (96%) patients with major blood count abnormalities, eg, anemia <10 g/dL and/or thrombocytopenia <100 × 10e9 /L in addition to monocytosis >1 × 10e9 /L and/or eosinophilia >10%, carried at least one additional molecular aberration irrespective of subtype. Three ASM-AHNMD patients progressed to ASM-AML, two solely carried an additional RUNX1 mutation, whereas the third patient had the molecular phenotype KIT-TET2-ASXL1-NRAS. The 3 patients with advanced SM without additional molecular aberrations shared common clinical characteristics. All 3 patients had >70% mast cell infiltration of the BM, hepatosplenomegaly (spleen volume 540 to 920 mL by MRI) and diffuse osteosclerosis. The serum tryptase levels were >200 µg/L in all 3 patients, >800 µg/L in 2 patients. Contrasting the high mast cell burden, all 3 patients only had mild cytopenia with hemoglobin levels persistently higher than 9.5 g/dL and platelets always exceeding 120 × 10e9 /L. However, all 3 patients additionally suffered from massive gastrointestinal symptoms (malabsorption with weight loss >10%, n = 2; histologically confirmed bowel infiltration, n = 2; hypoalbuminemia, n = 2; ascites, n = 2). There was no difference between serum tryptase values and BM mast cell infiltration on comparison of patients with additional aberrations vs those without additional aberrations (Table 1).

The mutational profiling predicts survival in SM

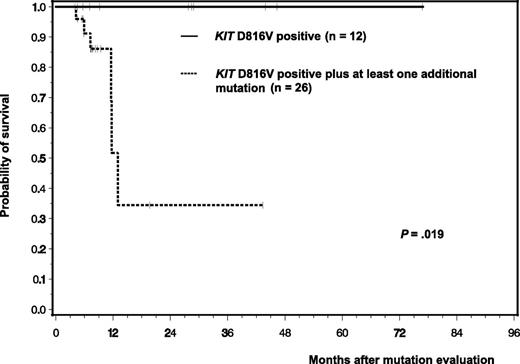

Clinical follow-up was available for 38/39 patients. Molecular analyses were performed median 45 months after first diagnosis (range 0-415). In advanced SM (26/38 with follow-up), 10 patients had a history of mastocytosis in the skin (MIS)/ISM (median 34 months, range 1-384) whereas 16 patients were primarily diagnosed in advanced phase. Six of 38 (16%) patients died, all of whom had advanced SM and lacked a history of cM/ISM. The 6 patients had also at least one additional mutation with 5 patients positive for ≥3 and 2 patients for ≥5 mutations. Median survival of all 26 patients with at least one additional mutation was 12 months. In contrast, none of the 12 patients died who only had KIT D816V mutation. This translated into a significant inferior survival (P = .019) for patients with additional mutations (Figure 2). All causes of death were disease-related.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival of 38 SM patients with respect to the individual mutation status irrespective of disease subtype: 12 patients with KIT D816V alone (ISM, n = 7; SSM, n = 2; ASM, n = 3) vs 26 patients with KIT D816V + at least one additional mutation (ISM, n = 3; SM-AHNMD, n = 4, ASM: n = 19). Patients with KIT D816V only are depicted by the continuous line; patients with additional mutations are depicted by the dashed line.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival of 38 SM patients with respect to the individual mutation status irrespective of disease subtype: 12 patients with KIT D816V alone (ISM, n = 7; SSM, n = 2; ASM, n = 3) vs 26 patients with KIT D816V + at least one additional mutation (ISM, n = 3; SM-AHNMD, n = 4, ASM: n = 19). Patients with KIT D816V only are depicted by the continuous line; patients with additional mutations are depicted by the dashed line.

Molecular analysis of microdissected cells

Analysis of KIT D816V and TET2 in 5 patients with (A)SM-AHNMD, who harbored both mutations in PB was performed on microdissected mast cells and CD15+ AHNMD cells. KIT D816V as well as TET2 mutations were present in mast cells of all patients. Both mutations were also seen in CD15+ cells of 3/5 patients (Table 2). In one additional case, the CD15+ cells were positive for the TET2 mutation but not for KIT D816V, and in the other case neither mutation was detected in the CD15+ fraction.

Discussion

Constitutively activated TK as a result of fusion genes, point mutations or insertions/deletions are the pathogenetic hallmark of MPN, and selective TKIs have shown excellent activity toward their targets in vitro. However, it remains unknown why JAK2 mutation positive MPN or KIT mutation positive SM only experience modest activity with relief of organomegaly and/or disease-related symptoms but no deep remissions.4,13 One possible explanation could be that the molecular pathogenesis of MPN and SM is in fact more complex and that other changes influence the clinical phenotype and the response to TKIs. Indeed, substantial somatic genetic heterogeneity has been described, eg, in myelofibrosis and CMML, which may have two or more potentially prognostically relevant mutations in genes involved in signaling, epigenetic regulation and/or the spliceosome machinery.20,27,32-34 In this study we have found more mutant genes in addition to KIT D816V in advanced SM compared with ISM. Although we cannot exclude the possibility of very low level mutations in ISM cases or mutations in other genes, our data suggest that the somatic landscape of advanced SM is indeed more complex and that this complexity is prognostically relevant.

Additional mutations in TET2, NRAS, ASXL1, DNMT3A, or CBL have already been identified in KIT D816V positive SM by other groups.15,16 TET2 mutations were the first to be reported (12/42 patients, 29%) but did not appear to alter prognosis in the study cohort analyzed.35 However, it was shown recently that KIT D816V and TET2 cooperated to give rise to a more aggressive disease in mice compared with that induced by KIT D816V alone.16 Traina et al found additional mutations in 3/15 ISM patients (ASXL1, DNMT3A, DNMT3A/TET2) and concluded that these mutations may affect prognosis, because an inferior survival was observed for SM mutated patients who were grouped based on the presence of combined TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations independent of KIT (P = .04) and sole TET2 mutations (P < .001).

Here we report on the identification of a variety of additional mutations in 89% of patients with advanced KIT D816V positive SM. The most frequently affected genes were TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and CBL, which were all initially identified in other myeloid neoplasms such as MDS or MDS/MPN.20,27,36 Although some of these mutations have also been identified in a small number of healthy elderly individuals,37 the relevant contribution to pathogenesis of SM is emphasized by the fact that a significant proportion of SM patients carried ≥3 mutations, some even ≥5 mutations. By using highly sensitive ultra deep sequencing, detection sensitivities of down to 1% to 2% could be achieved, although the impact of mutations with such low levels also remains unclear. In general, the mutation load of TET2 and SRSF2 mutations was always greater than 30% or 20%, respectively, whereas ASXL1, RUNX1, CBL, and KRAS mutations were sometimes also measured at levels <10% in some patients. In all these cases, KIT D816V and/or TET2 and/or SRSF2 were detected at levels >30%. In contrast, patients with advanced SM, who were negative for additional aberrations, presented clinically with a less aggressive phenotype and in particular lacked significant cytopenia, and none of these patients had died at the date of analysis.

Although our data cannot unambiguously identify the initiating lesions and subclonal structure, they are consistent with a general pattern of KIT, TET2, and SRSF2 being early events and other mutations more likely being secondary events. These findings may have important clinical implications because these mutations (1) are likely to contribute to the frequently observed morphological changes leading to diagnosis of AHNMD such as CMML, MDS/MPN, MDS, or HES/CEL, (2) may explain the significant anemia and thrombocytopenia as consequence of dysplasia and to a lesser extent by the degree of BM infiltration by mast cells, and (3) may contribute to prognosis and a negative impact on the efficacy of TKIs.

Although the follow-up period of our cohort is relatively short (median 8 months, range 4-77), OS was significantly inferior for patients with additional aberrations irrespective of disease subtype, thus highlighting the prognostic relevance of expanded mutational screening. Additional studies including sequential analyses in due course are warranted to work out the prognostic impact of individual mutations or the combination of mutations. Sequential samples were available however from one case: a 64-year old male patient who was diagnosed with KIT D816V positive SM-MDS in 2003. Informative material was available from three different time points during a 6-year follow-up, clearly demonstrating the complex pattern of molecular and chromosomal aberrations and associated clinical observations in an individual patient. Because of recurrent syncopes not responding to antimediator treatment, transfusion-dependent anemia, and the additional detection of a deletion del(5q), the patient was treated with lenalidomide (off-label use) from August 2006 to April 2008. When lenalidomide was stopped, the hemoglobin had increased to 13.5 g/dL. Follow-up analysis in 2010 showed an increase of serum tryptase, percentage of BM mast cells, and KIT D816V mutation load, whereas the del(5q) was detectable in 6/20 metaphases only. An additional follow-up in 2012 showed a further increase of SM disease burden (serum tryptase, KIT D816V mutation load) whereas the karyotype had become normal. Overall, the hemoglobin increased from 10.0 g/dL in 2006 to 16.3 g/dL in 2012. Based on our results, we have therefore now initiated a prospective follow-up of our patients to examine the changes of the various mutant alleles and the associated disease phenotypes in individual patients over time.

At least two new molecular features have now been identified as involved in phenotype, progression, and prognosis of SM patients: multilineage involvement by KIT D816V38 and multiple molecular aberrations in addition to KIT D816V.39 The clinical and morphological diversity of SM is therefore likely to be the result of qualitatively and quantitatively complex mutational patterns in different subclones and myeloid lineages, which is also consistent with the subclone-model of cancer stem cell evolution.40 From the diagnostic criteria, no prognostic markers have yet been established to discriminate among patients who may benefit from disparate treatment options, eg, TKI, chemotherapy, or allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The association of SM with a second hematologic neoplasm suggests the possibility that (1) advanced SM is a stem cell disorder with involvement of several lineages including monocytes and eosinophils, and/or (2) the AHNMD is in fact an independently evolving second neoplasm with an independent molecular profile. In our series, the presence of KIT D816V and TET2 mutations in mast cells and CD15+ cells in 3/5 patients with (A)SM-AHNMD suggests that the mutations were acquired in a common progenitor cell. One case shared only a TET2 mutation between CD15+ cells and mast cells, suggesting that KIT D816V in this case was a secondary event. A similar finding was observed in an SM-AHNMD group with associated JAK2 V617F positive myelofibrosis (n = 5), where the JAK2 mutation was found in 4/5 patients in microdissected mast cells.41 Supplementary studies are warranted to work out the individual qualitative and quantitative contribution of diverse mutations in different cell lineages but also the interaction of these molecular markers in individual patients. For example, it may be helpful to know KIT D816V low/other mutation(s) high mutation load in advanced SM or the genetic profile of blasts in ASM-AML that were recently reported to be KIT D816V negative in 7/10 (70%) patients.8 Most important, the molecular profile may become a useful prognostic marker prospectively, because the low frequency of additional mutations in ISM patients may suggest that benign forms of SM are mainly driven by KIT D816V alone, whereas additional mutations may be required for progression to advanced phases of the disease.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Daniel Hofmann for excellent technical assistance in the analysis of laser-microdissected cells.

This work was supported by the “Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung e.V.” (grant no. DJCLS R 09/29f and H 11/03).

Authorship

Contribution: S.S., V.G., A.F., M.M., T.E., P.E., T.H., K.S., C.W., and A.K. performed the laboratory work for the study; A.H., A.R., N.C.P.C., and W.-K.H. provided patient material; J.S., M.J., M.T., G.M., and A.R. collected patient information; C.W., H.-P.H., and K.S. reviewed the bone marrow biopsies; A.R. and N.C.P.C. prepared the study design; J.S., N.C.P.C., and A.R. wrote the paper; J.S. and M.P. performed the statistical analyses; A.H., W.-K.H., and P.V. revised the manuscript; and P.V., A.R., N.C.P.C., and K.S. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.S. and T.H. have equity ownership of MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory GmbH. A.K. and M.M. are employed by MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory GmbH. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andreas Reiter, III. Medizinische Universitätsklinik, Universitätsmedizin Mannheim, Theodor-Kutzer-Ufer 1-3, 68167 Mannheim, Germany; e-mail: andreas.reiter@umm.de.

References

Author notes

J.S., S.S., N.C.P.C., and A.R. contributed equally to this study.