In this issue of Blood, Baychelier et al identify a ligand for a major natural killer (NK) cell receptor that mediates natural cytotoxicity toward tumor cells, thus ending a search that lasted well over a decade.1

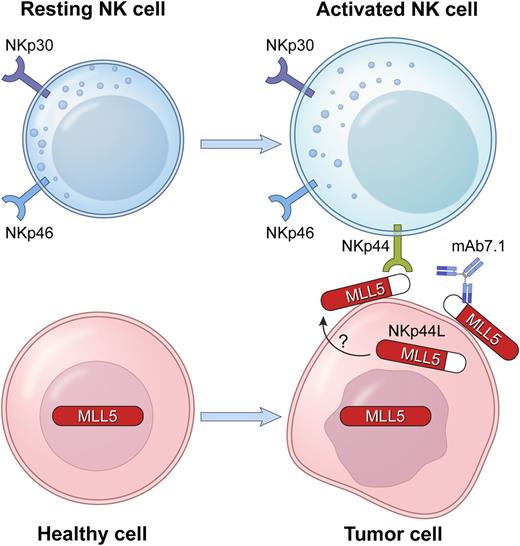

The natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp44, expressed on activated NK cells, binds a ligand, NKp44L, which is expressed at the surface of tumor cells. NKp44L is produced from an alternate transcriptional splice variant of the MLL5 gene, as a truncated MLL5 protein with a unique C-terminal sequence. MLL5 is an intracellular, nuclear protein. NKp44L is found in the cytoplasm and at the cell surface. The mAb 7.1, specific for NKp44L, blocks the killing of NKp44L+ target cells by NKp44+ NK cells.

The natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp44, expressed on activated NK cells, binds a ligand, NKp44L, which is expressed at the surface of tumor cells. NKp44L is produced from an alternate transcriptional splice variant of the MLL5 gene, as a truncated MLL5 protein with a unique C-terminal sequence. MLL5 is an intracellular, nuclear protein. NKp44L is found in the cytoplasm and at the cell surface. The mAb 7.1, specific for NKp44L, blocks the killing of NKp44L+ target cells by NKp44+ NK cells.

The natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCR) NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 are important mediators of NK cell cytotoxicity and contribute to the tumor immunosurveillance function of NK cells.2,3 Their expression is largely restricted to NK cells, and their role in tumor cell killing has been shown in blocking studies with specific Abs. Although NKp44 was discovered in the late 1990s,2,4 its activating cellular ligand has proven to be exceedingly difficult to find.3

NKp44 associates with a dimer of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-containing adaptor DAP12 to initiate signal transduction. Unlike the other 2 NCRs, NKp44 is not normally expressed on NK cells, but is induced after NK cell activation.4 Screening for a ligand using soluble NKp44–immunoglobulin fusion proteins has revealed binding on an array of tumor cell lines, but attempts at biochemical isolation of these ligands have been largely unsuccessful.

In the present study,1 an NKp44 ligand (NKp44L) was identified by a yeast-two hybrid screen using the extracellular portion of NKp44 to isolate interacting partners. The screen yielded an unusual isoform of the mixed lineage leukemia-5 (MLL5) protein, also known as lysine methyltransferase 2E. NKp44L represents a truncated form of MLL5 with a unique C-terminal sequence that is required for its localization at the cell surface and its interaction with NKp44. Biochemical detection of NKp44L and functional experiments were made possible by a mAb that had been obtained in a previous study by this group.5

The Debré group had shown that an NKp44 ligand was induced on uninfected CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected individuals and caused their lysis by autologous NK cells.5 The mAb 7.1, specific for this NKp44 ligand, was isolated in a screen to block the recognition of HIV-infected cells by autologous NKp44+ cells.5,6 Unlike MLL5, which is present in the nucleus and cytosol, NKp44L is not detected in the nucleus, but rather, at the cell surface, where it can interact with NKp44 on NK cells. It is unclear how it becomes exposed on the surface of tumor cells, although its expression at the surface of CD4+ T cells is induced by an HIV gp41-derived peptide that binds to the complement receptor gC1qR.6

An assortment of cellular and viral ligands of NCRs has been reported.3 For example, a ligand for NKp30, named BAT3 or BAG6, is an unusual nuclear protein that can be released by tumors in exosomes or as soluble protein to activate or inhibit NKp30, respectively.3 The only transmembrane, cell surface protein that has been identified as a cellular ligand for an NCR is B7-H6, a ligand for NKp30 expressed at the surface of tumor cells.3 Some of the viral ligands for NCRs may inhibit their function, such as the CMV pp65 protein that binds to NKp30.3 Similarly, proliferating cell nuclear antigen is a cellular inhibitory ligand of NKp44, which is released by tumor cells.3 The contribution of heparan sulfate and sulfated proteoglycans in the ligand specificity of NCRs has been reported.3 Interestingly, there is a putative glycosaminoglycan attachment site near the C terminus of NKp44L.1 The crystal structure of NKp44 includes a large positively charged groove, which may accommodate such a polysaccharide protein modification.7

Baychelier et al1 performed functional studies to provide further evidence for the NKp44–NKp44L interaction. The killing of several tumor targets mediated by NKp44 was blocked in the presence of anti-NKp44L mAb. The specificity of the interaction was confirmed by the transfection of NKp44L in NK-resistant EL4 cells, rendering them sensitive to lysis by NKp44+ NK cells. Moreover, transfection of a mutant NKp44L lacking the unique C-terminal portion into EL4 cells did not alter their resistance to NK cell lysis, implicating the C terminus of this ligand in both cell surface expression and recognition by NKp44.

The long-awaited identification of a cellular, activating ligand for NKp44 provides a new tool to examine how tumor cells may be recognized and eliminated by NK cells. In addition, the discovery of NKp44L is also relevant to our understanding of HIV control in infected individuals. Recent evidence suggests that the regulation of NKp44 expression plays an important role in HIV control by NK cells, along with efficient cytotoxic T-cell function.8 In that study,8 NK cells from elite controllers and long-term nonprogressors did not induce NKp44 after in vitro activation with interleukin-2. In contrast, in healthy controls and aviremic patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, NKp44 expression was clearly induced in activated NK cells. Therefore, the lack of NKp44 expression in controllers may protect uninfected CD4+ T cells, even after upregulation of NKp44L in these cells in response to HIV gp41 peptides. Certainly, deciphering the transcriptional regulation of NKp44 and of NKp44L will allow for the manipulation of these interactions toward therapeutic efforts not only in viral infections, but also against cancers in which NKp44+ NK cells can be used to target tumor cells.

NKp44L was given its name prior to the identification of the protein as an alternative splice form of MLL5. Given that additional ligands for NKp44 may exist, perhaps, one day it will become NKp44L1. It is also interesting that MLL5 is involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression.9 Given the enhanced sensitivity of cells undergoing mitosis to NK cell lysis,10 and the preferential expression of NKp44L in cell-cycle dysregulated transformed and tumor cells, it is worth exploring if, similar to MLL5, NKp44L surface expression is influenced by alterations in cell cycle regulation. Tackling the details of the regulation of its alternative splicing and its subcellular localization will allow for a clearer understanding of how NKp44L is presented as a danger signal for NK cell responses against tumors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.