Key Points

Mouse Dnmt3a R878H (human R882H) mutant protein inhibits wild-type Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b in murine ES cells, suggesting dominant-negative effects.

Abstract

Somatic heterozygous mutations of the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A occur frequently in acute myeloid leukemia and other hematological malignancies, with the majority (∼60%) of mutations affecting a single amino acid, Arg882 (R882), in the catalytic domain. Although the mutations impair DNMT3A catalytic activity in vitro, their effects on DNA methylation in cells have not been explored. Here, we show that exogenously expressed mouse Dnmt3a proteins harboring the corresponding R878 mutations largely fail to mediate DNA methylation in murine embryonic stem (ES) cells but are capable of interacting with wild-type Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. Coexpression of the Dnmt3a R878H (histidine) mutant protein results in inhibition of the ability of wild-type Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b to methylate DNA in murine ES cells. Furthermore, expression of Dnmt3a R878H in ES cells containing endogenous Dnmt3a or Dnmt3b induces hypomethylation. These results suggest that the DNMT3A R882 mutations, in addition to being hypomorphic, have dominant-negative effects.

Introduction

Recent studies identified somatic mutations of the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in ∼20% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML)1-3 and, with lower frequencies, in other hematological malignancies.4-7 DNMT3A functions cooperatively with its homolog DNMT3B to initiate de novo DNA methylation, whereas DNMT1 maintains DNA methylation patterns.8

Although multiple DNMT3A mutations have been identified in AML, the majority (∼60%) affect a single amino acid in the catalytic domain, resulting in substitution of Arg882 (R882) with histidine (most common) or other residues.1-3,9 R882-mutant proteins have decreased methyltransferase activity in vitro,2,3,10 which led to the notion that these are primarily loss-of-function mutations. However, almost all reported DNMT3A R882 mutations in AML are heterozygous, and both the wild-type (WT) and mutant alleles are expressed, raising the possibility of gain-of-function or dominant-negative effects. Indeed, heterozygous deletion of Dnmt3a in mice results in no apparent phenotype, although homozygous Dnmt3a-mutant mice die at ∼4 weeks of age (cause of lethality unknown).11 Ablation of Dnmt3a in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) results in progressive impairment of HSC differentiation and expansion of the HSC pool, but the animals were not reported to develop leukemia.12 In this study, we investigated the effects of DNMT3A R882 mutations in cells using mouse Dnmt3a-mutant proteins. We showed that the mutant proteins are capable of interacting with WT Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b and, when ectopically expressed in murine embryonic stem (ES) cells, induce hypomethylation, suggesting dominant-negative effects.

Study design

Plasmids

Plasmid vectors and oligonucleotides used to generate them are listed in supplemental Tables 1 and 2, respectively, on the Blood Web site.

Transfection, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting

Dnmt-mutant ES cells11 were used to generate stable clones.13 COS-7 cells were used for coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Transfection was performed using lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed using standard protocols. Antibodies used are listed in supplemental Table 3.

DNA methylation analysis

Results and discussion

Human DNMT3A and mouse Dnmt3a show high sequence identity (>96% overall, 100% in catalytic domain), and human R882 corresponds to murine R878 (supplemental Figure 1). Mutation of this residue impairs Dnmt3a methyltransferase activity in vitro.2,3,10 To confirm the effect in vivo, we performed a remethylation assay in [Dnmt3a,Dnmt3b] double knockout (7aabb) ES cells. These cells, after continuous culture for ∼5 months (∼80 passages), show substantial depletion of DNA methylation, which can be differentially remethylated by transfected Dnmt3 isoforms.13 Myc-tagged WT Dnmt3a/Dnmt3a2 or mutant proteins with R878 substituted with histidine (R878H), cysteine (R878C), or serine (R878S) were stably expressed in 7aabb cells. The expression of Myc-Dnmt3a/Dnmt3a2 was verified by immunoblotting (Figure 1A). Genomic DNA was isolated, and methylation of 2 repetitive elements, MSRs and IAP, was analyzed by methylation-sensitive restriction digestions and Southern blot (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 2A). The relative methylation levels (methylation scores) were determined by densitometry (supplemental Figure 3). Methylation of MSRs in representative samples was also quantified by bisulfite sequencing (supplemental Figure 4). Both MSRs and IAP were severely hypomethylated in 7aabb cells compared with WT (J1) ES cells, and expression of WT Dnmt3a/Dnmt3a2 largely restored methylation, as reported previously.13 In contrast, the ability of R878 mutants to restore methylation was severely impaired (Figure 1A; supplemental Figures 2A and 4B).

The R878 mutations severely impair the ability of Dnmt3a to methylate DNA but retain its ability to interact with wild-type Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. (A) Myc-tagged WT Dnmt3a/3a2 or R878 mutant (R878H [RH], R878C [RC], or R878S [RS]) was transfected into 7aabb ES cells (passage number: ∼80), and stable clones were obtained. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti–β-actin antibodies, and genomic DNA was digested with MaeII and analyzed by Southern hybridization with a probe specific for the MSRs. Untransfected 7aabb cells and WT (J1) ES cells were used as controls. Densitometry was used to determine the relative methylation levels (methylation scores), as described in supplemental Figure 3, and bisulfite sequencing was used to quantify methylation levels in representative samples (supplemental Figure 4). NT, not tested. (B) Flag-tagged and Myc-tagged WT and/or mutant Dnmt3a2 (as indicated) were cotransfected in COS-7 cells, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and the precipitated proteins (Myc IP), as well as total cell lysates (TCLs), were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (C) Similar experiments as in B except that Flag-Dnmt3b1 or -Dnmt3b2 was used instead of Flag-Dnmt3a2. The Flag- and Myc-tagged proteins and the immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy chain are indicated.

The R878 mutations severely impair the ability of Dnmt3a to methylate DNA but retain its ability to interact with wild-type Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. (A) Myc-tagged WT Dnmt3a/3a2 or R878 mutant (R878H [RH], R878C [RC], or R878S [RS]) was transfected into 7aabb ES cells (passage number: ∼80), and stable clones were obtained. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti–β-actin antibodies, and genomic DNA was digested with MaeII and analyzed by Southern hybridization with a probe specific for the MSRs. Untransfected 7aabb cells and WT (J1) ES cells were used as controls. Densitometry was used to determine the relative methylation levels (methylation scores), as described in supplemental Figure 3, and bisulfite sequencing was used to quantify methylation levels in representative samples (supplemental Figure 4). NT, not tested. (B) Flag-tagged and Myc-tagged WT and/or mutant Dnmt3a2 (as indicated) were cotransfected in COS-7 cells, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and the precipitated proteins (Myc IP), as well as total cell lysates (TCLs), were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (C) Similar experiments as in B except that Flag-Dnmt3b1 or -Dnmt3b2 was used instead of Flag-Dnmt3a2. The Flag- and Myc-tagged proteins and the immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy chain are indicated.

Dnmt3a interacts with itself, Dnmt3b, and Dnmt3L (a Dnmt3-like protein with no catalytic activity) to form homo- and hetero-oligomers.14-20 Structural studies revealed that the Dnmt3a C-terminal domain provides 2 interfaces for protein-protein interactions: a hydrophilic interface that mediates Dnmt3a-3a contact and a hydrophobic interface that mediates Dnmt3a-3a, 3a-3L, and perhaps 3a-3b contacts.17 Notably, R878 is located within the hydrophilic self-interaction interface (supplemental Figure 1).17 To determine whether the R878 mutations affect Dnmt3a self-interaction, we transiently transfected Flag-Dnmt3a2 and Myc-Dnmt3a2 or Myc-Dnmt3a2:R878 mutants in COS-7 cells and performed coimmunoprecipitation assays. As shown in Figure 1B, none of the mutations disrupted Dnmt3a2 self-interaction. Even under stringent conditions (high salt concentrations or 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), the Dnmt3a2-3a2 and Dnmt3a2-R878H interactions showed no apparent difference (supplemental Figure 5A). Indeed, Dnmt3a2:R878H was able to interact with itself (supplemental Figure 5B). Pull-down experiments using recombinant proteins produced in Escherichia coli confirmed that Dnmt3a2:R878H directly interacts with WT Dnmt3a2 (supplemental Figure 5C). These results were consistent with previous reports that mutations within the hydrophilic interface, including R878H (human R882H), disrupt Dnmt3a tetramerization, but not dimerization (mediated by the hydrophobic interface).19,21 Coimmunoprecipitation experiments also revealed that Dnmt3a2:R878H was able to interact with Dnmt3b1/3b2 and Dnmt3L (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 6).

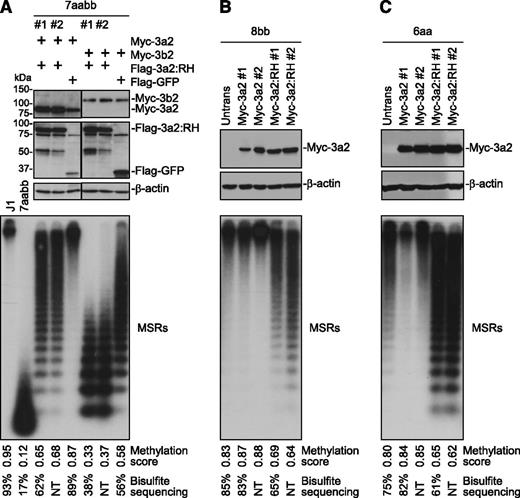

We then asked whether R878H mutant proteins would interfere with WT Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b activities. To this end, we stably expressed in 7aabb cells Myc-tagged Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b isoforms and Flag-tagged Dnmt3a:R878H, Dnmt3a2:R878H, or green fluorescent protein (GFP; control) simultaneously from a single plasmid by using the “self-cleaving” P2A peptide.22 The levels of the Myc- and Flag-tagged proteins were determined by immunoblotting, and R878H and GFP clones with similar levels of WT Dnmt3a or Dnmt3b isoforms were used for DNA methylation analysis (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 7A-B). As expected, expression of Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b isoforms (along with GFP) resulted in substantial restoration of DNA methylation in 7aabb cells. Dnmt3b was less efficient than Dnmt3a in methylating MSRs (Figure 2A; supplemental Figures 4C and 7A-B), whereas Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b were equally efficient in methylating IAP (supplemental Figure 2B), as previously reported.13 Notably, Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b-mediated methylation of MSRs and IAP was inhibited in the presence of R878H mutant proteins (Figure 2A; supplemental Figures 2B, 4C, and 7A-B). To determine whether R878H mutant proteins would antagonize endogenous Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, we transfected Myc-Dnmt3a2 or -Dnmt3a2:R878H in Dnmt3b−/− (8bb) and Dnmt3a−/− (6aa) ES cells, and stable clones expressing similar levels of WT Dnmt3a2 or Dnmt3a2:R878H were analyzed (Figure 2B-C). Expression of Dnmt3a2:R878H in both 8bb and 6aa cells led to hypomethylation of MSRs and IAP, whereas expression of WT Dnmt3a2 either had no obvious effect or resulted in slight increases in methylation compared with untransfected cells (Figure 2B-C; supplemental Figures 2C-D and 4D-E). A similar effect was observed when Dnmt3a:R878H was expressed in 8bb cells (supplemental Figure 7C).

Dnmt3a2:R878H antagonizes WT Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. (A) Myc-tagged Dnmt3a2 or Dnmt3b2 and Flag-tagged Dnmt3a2:RH or GFP (control) were expressed simultaneously in 7aabb cells (passage number: ∼80), and stable clones were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag, anti-Myc, and anti–β-actin antibodies and by Southern blot for methylation of MSRs. J1 and untransfected 7aabb ES cells were used as controls. (B-C) Myc-tagged Dnmt3a2 or Dnmt3a2:RH was transfected into (B) 8bb or (C) 6aa ES cells, and stable clones were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti–β-actin antibodies and by Southern blot for methylation of MSRs. Densitometry was used to determine the relative methylation levels (methylation scores), as described in supplemental Figure 3, and bisulfite sequencing was used to quantify methylation levels of representative samples (supplemental Figure 4). NT, not tested. To avoid the effect of culturing time on DNA methylation, stable clones expressing the control and R878H proteins were generated from same batches of parental cells and were cultured for the same periods of time (in most cases, 7-10 days for generating stable clones and 7-10 days for expansion) before genomic DNA was isolated.

Dnmt3a2:R878H antagonizes WT Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. (A) Myc-tagged Dnmt3a2 or Dnmt3b2 and Flag-tagged Dnmt3a2:RH or GFP (control) were expressed simultaneously in 7aabb cells (passage number: ∼80), and stable clones were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag, anti-Myc, and anti–β-actin antibodies and by Southern blot for methylation of MSRs. J1 and untransfected 7aabb ES cells were used as controls. (B-C) Myc-tagged Dnmt3a2 or Dnmt3a2:RH was transfected into (B) 8bb or (C) 6aa ES cells, and stable clones were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti–β-actin antibodies and by Southern blot for methylation of MSRs. Densitometry was used to determine the relative methylation levels (methylation scores), as described in supplemental Figure 3, and bisulfite sequencing was used to quantify methylation levels of representative samples (supplemental Figure 4). NT, not tested. To avoid the effect of culturing time on DNA methylation, stable clones expressing the control and R878H proteins were generated from same batches of parental cells and were cultured for the same periods of time (in most cases, 7-10 days for generating stable clones and 7-10 days for expansion) before genomic DNA was isolated.

It has been debated whether DNMT3A mutations contribute to leukemogenesis due to haploinsufficiency or gain-of-function/dominant-negative effects or both. Our finding that the R878H-mutatant protein antagonizes WT Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in murine ES cells provides experimental data supporting dominant-negative effects. The mechanism by which the mutant protein exerts its inhibitory effect remains to be elucidated. One possibility is that the mutant protein, capable of dimerizing but not tetramerizing,21 interacts with WT Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b to form functionally deficient complexes. Oligomerization of Dnmt3a has been shown to be necessary for processive methylation, proper DNA binding, and heterochromatic localization.19-21 It is worth noting that methylation changes in repetitive sequences in murine ES cells served as our readout for Dnmt functions, which may not necessarily reflect the consequences of the R882 mutations on methylation of specific loci in human AML cells. Furthermore, differences between DNA methylation complexes in ES and hematopoietic cells, such as expression of Dnmt3L (absent in hematopoietic cells), may affect mutant-Dnmt3a activities. Nevertheless, the striking effects of the mutant protein on DNA methylation in murine ES cells suggest that dominant-negative effects very likely contribute to methylation alterations in AML.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeesun Kim and Rachel E. Rau for discussion and Mark Bedford for providing the anti-GST antibody.

This study was supported by Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas award R1108 (to T.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: T.C. and M.A.G. conceived the project; S.J.K., H.Z., S.H., A.K.S., and T.C. performed the experiments; S.J.K., H.Z., A.K.S., and T.C. analyzed the data; S.J.K. and T.C. wrote the manuscript; and S.J.K., H.Z., S.H., A.K.S., M.A.G., and T.C. critically reviewed it.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Taiping Chen, Department of Molecular Carcinogenesis, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Science Park–Research Division, 1808 Park Rd 1C, PO Box 389, Smithville, TX 78957; e-mail: tchen2@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

S.J.K. and H.Z. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 1. The R878 mutations severely impair the ability of Dnmt3a to methylate DNA but retain its ability to interact with wild-type Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. (A) Myc-tagged WT Dnmt3a/3a2 or R878 mutant (R878H [RH], R878C [RC], or R878S [RS]) was transfected into 7aabb ES cells (passage number: ∼80), and stable clones were obtained. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti–β-actin antibodies, and genomic DNA was digested with MaeII and analyzed by Southern hybridization with a probe specific for the MSRs. Untransfected 7aabb cells and WT (J1) ES cells were used as controls. Densitometry was used to determine the relative methylation levels (methylation scores), as described in supplemental Figure 3, and bisulfite sequencing was used to quantify methylation levels in representative samples (supplemental Figure 4). NT, not tested. (B) Flag-tagged and Myc-tagged WT and/or mutant Dnmt3a2 (as indicated) were cotransfected in COS-7 cells, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and the precipitated proteins (Myc IP), as well as total cell lysates (TCLs), were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (C) Similar experiments as in B except that Flag-Dnmt3b1 or -Dnmt3b2 was used instead of Flag-Dnmt3a2. The Flag- and Myc-tagged proteins and the immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy chain are indicated.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/25/10.1182_blood-2013-02-483487/4/m_4086f1.jpeg?Expires=1769333394&Signature=qGtG1q6IbLFjQhlw-gBEBvXhtavSJN2aoBBe2kQoFxq~dnyffqJ8RprgS~cboPd0DYeJSyZm~mdREYx7nGDy92E5De7mREbXLYxgcxlH2cjEreW4tmMqXvsc2wh7seV8XLN2E3PcpgOcWVUnao9KgoC7iQm~mtvvnJ~D5MSbPqvB18QpKqBfctBAm5WgD9XPpCIViDPqlIpkgvWNwqnlkJeVVCAIc~Ou4MXqcXVxp7KC7crbZ5HwmzMy~UKS6GzrrtnHft17ReYhlQoANXG8q3k16jyuUBeKUrBhMDDlZd0CpH6jyaLJXrl8ljUnVeb8RYKq1KdVuJk62ZPP8bUgxg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)