Key Points

Gain-of function mutation of IL7Rα induces lymphoid leukemia as well as myeloproliferative disease.

In vivo oncogenicity of mutant IL7Rα is influenced by the differentiation stage at which it occurs.

Abstract

Somatic gain-of-function mutations in interleukin 7 receptor α chain (IL7Rα) have been described in pediatric T and B acute lymphoblastic leukemias (T/B-ALLs). Most of these mutations are in-frame insertions in the extracellular juxtamembrane-transmembrane region. By using a similar mutant, a heterozygous in-frame transmembrane insertional mutation (INS), we validated leukemogenic potential in murine hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, using a syngeneic transplantation model. We found that ectopic expression of INS alone in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells caused myeloproliferative disorders, whereas expression of INS in combination with a Notch1 mutant led to the development of much more aggressive T-ALL than with wild-type IL7Rα. Furthermore, forced expression of INS in common lymphoid progenitors led to the development of mature B-cell ALL/lymphoma. These results demonstrated that INS has significant in vivo leukemogenic activity and that the lineage of the resulting leukemia depends on the developmental stage in which INS occurs, and/or concurrent mutations.

Introduction

Interleukin 7 (IL7) is essential for T-cell development and homeostasis.1 Its cognate receptor (IL7R) forms a heterodimer composed of the α chain (IL7Rα) and common γ chain; binding of IL7 to IL7R triggers activation of Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling and the PI3K/v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (Akt) pathways.1

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that dysregulation of the IL7 signaling axis may be implicated in lymphoid malignancies. For example, IL7 transgenic mice develop T- and B-cell lymphomas,1 and human primary T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cells respond to IL7 in vitro1 and in vivo.2 Moreover, recent findings describing IL7Rα gain-of-function mutations in pediatric ALL and a T-ALL cell line have provided direct evidence that the IL7-IL7R axis plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of human ALL.3-6

Although the gain-of-function properties of these mutants have been precisely studied in vitro,3-5 their leukemogenic potential in vivo has not been well studied. One study reported that T-cell leukemogenesis was triggered by an IL7Rα mutant.5 However, they used murine IL7-dependent D1 progenitor T-cell lines derived from p53-knockout mice,7 which spontaneously develop T-cell lymphoma,8,9 and this specific animal model may not be generally applicable.

To extend these observations, we demonstrate the in vivo leukemogenic potential of such a mutant when expressed in primary hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by using a IL7Rα mutant, which was previously identified in a T-ALL cell line.6

Methods

Mice

Six- to 12-week-old Balb/c mice were used for all experiments. Lineage depletion of bone marrow (BM) or embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) fetal liver was performed by the EasySep Mouse Hematopoietic/Progenitor Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). Via tail vein injection, 1 × 106 Lineage− BM/fetal liver cells (lin− cells), pro-B, or Thy1+T cell progenitors were injected into lethally (8 Gy) or sublethally (4 Gy) irradiated recipients. Mice were maintained in accordance with institutional animal care guidelines (Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo). Detailed methods are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results and discussion

In vitro transforming activity of the mutant IL7Rα, INS

Consistent with previous report, sequencing analysis of exon 6 of the IL7Rα gene, mainly encoding the transmembrane domain, identified a heterozygous in-frame transmembrane insertional mutation (INS) in the T-ALL cell line DND-41.6 Forced expression of INS exerted transforming activity in Ba/F3 cells, as revealed by acquisition of cytokine-independent growth (supplemental Figure 1A-C, found on the Blood website) as well as the autonomous phosphorylation of Stat1, Stat3, Stat5, and Akt (supplemental Figure 1D). In addition, transient expression of IL7Rα in human embryonic kidney 293 cells leads to autonomous tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1 only in those expressing INS (supplemental Figure 1D, left), suggesting that INS constitutively activated IL7R downstream signals via Jak1. As INS falls within the same category of reported mutation of IL7Rα,3-6 we decided to use INS as a representative gain-of-function IL7Rα mutation for further experiments.

INS in stem/progenitor cells caused myeloproliferative disorders

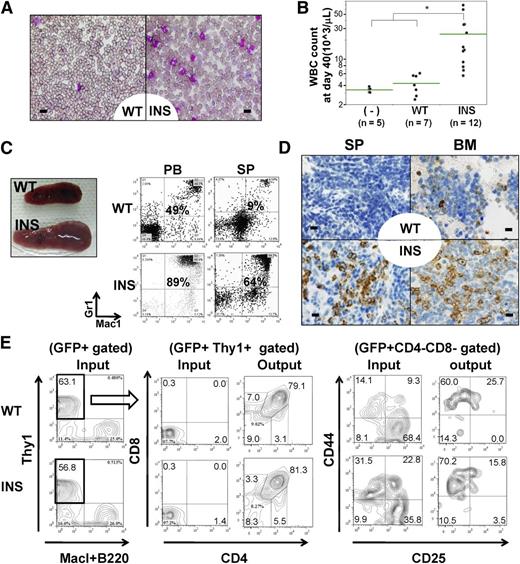

The leukemogenic activity of INS and wild-type (WT) IL7Rα was assessed by retroviral transduction of Lin− cels. Within 6 to 9 weeks after transplantation, recipient mice transplanted with INS Lin− cells, but not WT Lin− cells, developed myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs) characterized by splenomegaly, leukocytosis, and polycythemia (Figure 1A-C, right; supplemental Figures 1D and 3C-D). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) and morphological analysis revealed a marked increase in Mac1++Gr-1++ mature myeloid cells in the peripheral blood (PB), spleen (SP), and BM (Figure 1C-D; supplemental Figures 2 and 4). An increase of Ter119+ CD71+ immature erythroblast was also noted in SP and BM (supplemental Figure 4, SP; data not shown). INS-induced MPD was oligoclonal, as evidenced by Southern blot analysis (supplemental Figure 5, left). A similar disease phenotype was also observed in mice transplanted with Lin−c-Kit++Sca1++ (KSL) fractions transduced with INS (supplemental Figures 3A-B,E and 4). Both B- and T-cell development were severely perturbed in INS recipient mice (supplemental Figure 4). As transplantation of INS-transduced KSL cells resulted in preferential expansion of myeloid progenitor–enriched Lin−c-Kit++Sca1− fraction (supplemental Figure 6), we speculate that in vitro transforming activity of INS skewed myeloid progenitor expansion at the expense of common lymphoid progenitor Lin–c-kitlowSca1+ IL7Rα+ (CLP) expansion, through which normal lymphopoiesis might be perturbed. This was also supported by the fact that INS exerted transforming activity in input KSL cells, as well as resultant myeloid progenitors ex vivo, as revealed by colony-forming cell assay (supplemental Figure 7). It was previously reported that forced expression of wild-type murine IL7Rα into IL7Rα knockout BM progenitors induces a very similar MPD phenotype, including splenomegaly resulting from neutrophilia.10 Consistent with this report, transduced WT appeared to induce some degree of increase in myeloid fraction and neutrophilia in PB and SP compared with that of mock increase of myeloid fraction and neutrophilia in PB (supplemental Figure 4). Importantly, the magnitude was quite different, as we could not find a statistically significant difference of SP weight in mock and WT (n = 4 each; P = .61, 1-way analysis of variance; supplemental Figure 3C). This is in contrast to the difference of INS (n = 4) and WT (P < .01; supplemental Figure 3C). WT-induced mild myeloid expansion was accompanied by concomitant increase in lymphoid subset in PB, SP, and BM, specifically CD19+ B-cell fractions (supplemental Figure 4). Considering the fact that the phenotype of WT-recipient mice was different from that of mock (supplemental Figure 4), it should be mentioned that we could not rule out the possibility that the phenotype elicited by INS is in part a result of the effect of IL7R overexpression per se, irrespective of its mutational status. The major difference from the previous report was that they rescued the loss-of-function phenotype of IL7Rα by ectopic expression of IL7Rα.10

In vivo transforming activity of INS. (A-D) Lin− cells were retrovirally transduced with mock vectors (mock), WT, or INS, followed by injection into lethally irradiated congenic mice. (A) May-Giemsa staining of PB smears at day 40, showing marked leukocytosis consisting predominantly of mature myeloid cells. (B) White blood cell count at day 40. *P < .05 (analysis of variance; INS vs WT or mock recipient mice). (C) FACS of the PB and SP at day 40, showing an increase in Mac-1+/Gr-1+ myeloid cells. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) of SP and BM specimens by anti-myeloperoxidase, indicating an increase in the number of myeloid cells in INS recipient mice. Bars represent (A) 10 μm and (D) 20 μm. (E) Demonstration of in vivo reconstitutive capacity of hIL7R (WT/INS) transduced T-cell progenitors. Lin− kit+ stem/progenitor cells were cultured on OP9-DL1 stromal layer for 7days, supplemented with mIL7+ human Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3-ligand, which allowed them to differentiate into Thy1+CD25−CD44+DN1 immature T-cell progenitor fractions. These cells were retrovirally transduced with WT/INS vector. The resultant cells were allowed to expand on OP9-DL1 stroma for additional 7 to 10 days, and developed into CD25+CD44−DN3 immature T-cell progenitor fractions. These Thy1+ cells were green fluorescent protein (GFP)-sorted and intravenously injected into sublethally irradiated mice. The resultant GFP+ thymic seeding progenitors (denoted as “input”) in recipient mice of WT and INS at day 52 was shown (denoted as “output”).

In vivo transforming activity of INS. (A-D) Lin− cells were retrovirally transduced with mock vectors (mock), WT, or INS, followed by injection into lethally irradiated congenic mice. (A) May-Giemsa staining of PB smears at day 40, showing marked leukocytosis consisting predominantly of mature myeloid cells. (B) White blood cell count at day 40. *P < .05 (analysis of variance; INS vs WT or mock recipient mice). (C) FACS of the PB and SP at day 40, showing an increase in Mac-1+/Gr-1+ myeloid cells. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) of SP and BM specimens by anti-myeloperoxidase, indicating an increase in the number of myeloid cells in INS recipient mice. Bars represent (A) 10 μm and (D) 20 μm. (E) Demonstration of in vivo reconstitutive capacity of hIL7R (WT/INS) transduced T-cell progenitors. Lin− kit+ stem/progenitor cells were cultured on OP9-DL1 stromal layer for 7days, supplemented with mIL7+ human Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3-ligand, which allowed them to differentiate into Thy1+CD25−CD44+DN1 immature T-cell progenitor fractions. These cells were retrovirally transduced with WT/INS vector. The resultant cells were allowed to expand on OP9-DL1 stroma for additional 7 to 10 days, and developed into CD25+CD44−DN3 immature T-cell progenitor fractions. These Thy1+ cells were green fluorescent protein (GFP)-sorted and intravenously injected into sublethally irradiated mice. The resultant GFP+ thymic seeding progenitors (denoted as “input”) in recipient mice of WT and INS at day 52 was shown (denoted as “output”).

Neither of these recipient mice developed overt leukemia throughout the median follow-up period of 5 months (WT, n = 28; INS, n = 22), suggesting that additional transforming events are required for clonal evolution to aggressive leukemia. Considering the fact that recipient mice for hematopoietic stem cells transduced with constitutively active Akt or signal transducer and activator of transcription-5 also developed similar diseases together,11,12 this MPD phenotype is likely to be induced by stem cells ectopically expressing INS.

Nononcogenic consequence of INS in T-cell progenitors

Next, we wished to test the effect of INS on T-cell precursors. Toward this aim, we cocultured Lin− kit+ stem/progenitor cells for 7 days, which allowed the emergence of Thy1+CD25−CD44+DN1 immature T-cell-progenitor fractions (data not shown). These cells were transduced by retroviral transduction of the WT/INS vector. The resultant transduced cells were allowed to expand on OP9 expressing the Notch ligand Delta-like 1 (OP9-DL1) stroma for an additional 7 to 10 days, which allowed them to develop Thy1+CD4−CD8−CD25−CD44+DN1 to DN3 CD25+CD44−DN3 immature T-cell-progenitor fractions (Figure 1E). The resultant Thy1+ cells were GFP sorted and injected into sublethally irradiated mice. As a result, we could detect stable engraftment of GFP+ T-cell progenitors in recipient mice from day 40 to day 50 in thymus (Figure 1E) and CD4 or CD8 single-positive cells in the periphery, such as SP or PB (data not shown). Neither of these recipient mice developed overt leukemia throughout the median follow-up period of 106 days (WT and INS, n = 12 each). We speculate that this might be partly attributable to the limited engraftment of WT/INS-transduced T-cell progenitors in thymus (data not shown).

INS exacerbates the in vivo oncogenic activity of Notch1

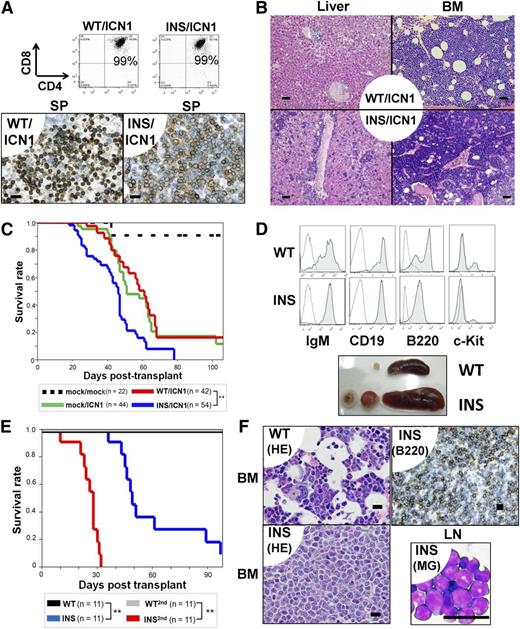

INS-like mutations were reported to occur in 10% of T-ALL patients.3,4 In contrast, Notch1 mutations were more frequently found in T-ALL patients and were equally distributed between patients with WT and INS.4, The DND-41 cell line carries both INS and Notch1 mutations.6,13 Moreover, IL7 signaling coordinates with Notch1 in proper T-cell developmental programming.14,15 We hypothesized that INS may cooperate with active Notch1 mutants in T-cell leukemogenesis. Therefore, Lin− cells were transduced with mock or IL7Rα-WT/INS along with an active form of intracellular Notch1 (ICN1), followed by syngeneic transplantation. As reported previously,16 within 4 to 6 weeks after transplantation, all mice developed T-ALL, characterized by extrathymic expansion of leukemic cells (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 8B). Clonality of INS/ICN1-induced leukemia was confirmed by Southern blot analysis around day 35 (supplemental Figure 5, right). Despite similar immunophenotypes (CD3+CD4+CD8+TCR-β+) between WT/ICN1 and INS/ICN1 cells (Figure 2A, Upper; supplemental Figures 8A and 9), histological examinations of the liver, SP, and BM in recipient mice revealed that systemic expansion of INS/ICN1-Lin− cells was much more aggressive than that of WT/ICN1− and mock/ICN1−Lin− cells (Figure 2A, Lower, and 2B). Furthermore, the median survival time of INS/ICN1 mice (44 days; n = 54) was significantly shorter than that of mock/ICN1 (60 days; n = 44) and WT/ICN1 (57 days; n = 42) mice (P < .001 by log-rank test; Figure 2C). Taken together, INS clearly exaggerated ICN1-induced T-ALL.

INS synergized with active Notch1 (A-C) and exerted transforming activity in CLPs (D-F) in vivo. (A-C) Lin− cells were cotransfected with vectors encoding the ICN1 gene (mock, ICN1) and the hIL7R gene (mock, WT, INS), followed by injection into lethally irradiated congenic mice. (A, upper) FACS analysis of the SP from WT/ICN1 or INS/ICN1 recipient mice at day 40. Data were obtained from GFP+ (marker for the ICN1 gene) and rat CD2+ (marker for the hIL7R gene) fractions. (A, lower) IHC of SP specimens using anti-CD3 antibodies from WT/ICN1 (left) and INS/ICN1 (right) recipient mice. Bar represents 20 μm. (B) Histological findings of liver (left 2 panels) and BM (right 2 panels) from WT/ICN1 (upper) and INS/ICN1 (lower) recipient mice (hematoxylin and eosin stain). Bar represents 50 μm. (C) Survival curves of recipient mice (mock/mock, n = 22; mock/ICN1, n = 44; WT/ICN1, n = 42; INS/ICN1, n = 54) **P < .01 (log-rank test). (D-F) CLPs transfected with hIL7R constructs were expanded in vitro for 18 days and injected into sublethally irradiated congenic mice. (D, top 2 panels) FACS analysis of the BM: WT recipient mice at day 60 (WT) and INS recipient mice at day 60 (INS). Data are obtained from GFP+ gated fractions. Open histogram, isotype control; shaded histogram, specific staining. (D, lower) Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy developed in CLPs-INS recipient mice at day 60 (denoted as “INS”). (E) Survival curves of recipient mice (n = 11 for each condition). **P < .01 (log-rank test, INS vs WT or INS vs INS2nd). (F) Histological findings: BM specimens from WT recipient mice (upper left) and INS recipient mice at day 60 by hematoxylin and eosin stain (lower left) or by IHC of B220+ cells (upper right). Lymph node cytospin from INS recipient mice at day 60 by May-Giemsa stain (lower right). Bar represents 20 μm. WT, WT primary recipients; INS, INS primary recipients; WT-2nd, WT day 30 BM secondary recipients; INS-2nd, INS day 30 BM secondary recipients.

INS synergized with active Notch1 (A-C) and exerted transforming activity in CLPs (D-F) in vivo. (A-C) Lin− cells were cotransfected with vectors encoding the ICN1 gene (mock, ICN1) and the hIL7R gene (mock, WT, INS), followed by injection into lethally irradiated congenic mice. (A, upper) FACS analysis of the SP from WT/ICN1 or INS/ICN1 recipient mice at day 40. Data were obtained from GFP+ (marker for the ICN1 gene) and rat CD2+ (marker for the hIL7R gene) fractions. (A, lower) IHC of SP specimens using anti-CD3 antibodies from WT/ICN1 (left) and INS/ICN1 (right) recipient mice. Bar represents 20 μm. (B) Histological findings of liver (left 2 panels) and BM (right 2 panels) from WT/ICN1 (upper) and INS/ICN1 (lower) recipient mice (hematoxylin and eosin stain). Bar represents 50 μm. (C) Survival curves of recipient mice (mock/mock, n = 22; mock/ICN1, n = 44; WT/ICN1, n = 42; INS/ICN1, n = 54) **P < .01 (log-rank test). (D-F) CLPs transfected with hIL7R constructs were expanded in vitro for 18 days and injected into sublethally irradiated congenic mice. (D, top 2 panels) FACS analysis of the BM: WT recipient mice at day 60 (WT) and INS recipient mice at day 60 (INS). Data are obtained from GFP+ gated fractions. Open histogram, isotype control; shaded histogram, specific staining. (D, lower) Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy developed in CLPs-INS recipient mice at day 60 (denoted as “INS”). (E) Survival curves of recipient mice (n = 11 for each condition). **P < .01 (log-rank test, INS vs WT or INS vs INS2nd). (F) Histological findings: BM specimens from WT recipient mice (upper left) and INS recipient mice at day 60 by hematoxylin and eosin stain (lower left) or by IHC of B220+ cells (upper right). Lymph node cytospin from INS recipient mice at day 60 by May-Giemsa stain (lower right). Bar represents 20 μm. WT, WT primary recipients; INS, INS primary recipients; WT-2nd, WT day 30 BM secondary recipients; INS-2nd, INS day 30 BM secondary recipients.

Forced expression of INS in B-cell progenitors caused mature B-ALL/lymphoma

Because the IL7Rα gene is transcriptionally active in common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs; Lin−c-kitlowSca1+ IL7Rα+) and their progenies and not expressed in stem cell compartments,17 the INS allele could target the same cell populations. Then, CLPs were transduced with INS or WT IL7Rα and cultured on the OP9 stromal layer with a cytokine cocktail for 18 days, followed by transplantation of resulting pro-B cells into syngeneic recipient mice (supplemental Figure 10A). All but 1 of the INS-CLP recipients died of mature B-ALL/lymphoma, whereas no WT-CLP recipients died (P < .01; Figure 2D-E). Autopsy specimens revealed massive infiltration of B220+ leukemic blasts into the BM, SP, and lymph nodes (Figure 2F; data not shown). This mature B-cell ALL/lymphoma was transplantable to secondary recipients, resulting in more aggressive mature B-ALL/lymphoma with much shorter survival periods (Figure 2E). INS-induced mature B-ALL/lymphoma was biclonal, as evidenced by Southern blot analysis (supplemental Figure 5, right). Under these experimental conditions, INS-CLPs had already committed to the cytokine-independent clonogenic pro-B cells before transplantation (supplemental Figure 10B-C; data not shown).

Finally, we wished to identify the downstream signals involved in INS-induced leukemogenesis. Using microarray analysis (Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE51211) of the resultant transformed cells in vitro and in vivo, we performed a comparative analysis of gene expression profiles from WT and INS-transduced hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, as well as resultant leukemia cells that developed in vivo. As a result, we found a list of candidate genes (n = 6133) that were up- or downregulated by INS in comparison with WT. Among those genes, by reviewing hierarchical clustering analysis, several genes could be candidate mediators downstream of INS in comparison with WT, including hairy and enhancer of split-1 (HES1) for MPD, proviral insertion site in Moloney murine leukemia virus 1 (PIM1) for B-ALL, and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) for T-ALL (supplemental Figure 11). Quantitative RT-PCR verified their differential expression in comparison with WT (supplemental Figure 12). Putative involvement of these genes in INS-induced leukemogenesis was supported by previous data reporting the significance of HES1 overexpression reported in advanced chronic myelogenous leukemia,18 PIM1 activation involved in pre-B-cell transformation,19 PIM1 overexpression reported in B-ALL,20 and high-level expression of IGF1R in T-ALL.20,21 In addition, we performed gene set enrichment analysis22 to find significant overlaps between INS/ICN1 (in comparison with WT/ICN1) gene expression signature and gene sets present in the public database (supplemental Discussion). As a result, we found that in vivo INS/ICN1 was characterized by overexpression of interferon (IFN)-stimulated genes23 and IGF1-signal-related genes,24 suggesting constitutive activation of IFN− as well as the IGF1− signal pathway (supplemental Figures 13 and 14; supplemental Tables 2 and 3). These are consistent with the previous report that JAK1-mutated T-ALL samples were characterized by the IFN-pathway23 signature, as well as our findings of a higher IGF1R transcript level in INS/ICN1 cells compared with that of WT/ICN1 (supplemental Figures 11 and 12).

In conclusion, we provided evidence that INS has significant in vivo leukemogenic activity and that determination of the lineage of resulting leukemias depends on the developmental stage during which they occur and/or concurrent mutations. In addition, as far as we know, this is the first report in which transformation of CLP leading to in vivo malignancy is shown. This is also of general relevance for the field of lymphoid malignancies. Given that either IL7Rα or Jak1 gain-of-function mutations have been found in approximately 10%3-5 or 19%25 of T-ALL patients and that IFN- pathway signatures have been associated with Jak1-mutated T-ALL,23 it is fairly certain that IFN-pathway signatures induced by aberrant IL7R/Jak1 axis might substantially contribute to the pathogenesis of T-ALL in close association with activating mutations in the Notch pathways.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgment

We thank Kana Minegishi and Kazuo Ogami for their help.

Authorship

Contribution: K.Y., N.Y., and K.I. performed experiments; K.Y. wrote the manuscript; A.H., A.K., and K.H. provided vital reagents; and A.T. supervised the research.

Conflict-of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Arinobu Tojo, Department of Hematology-Oncology, Research Hospital, Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8639, Japan; e-mail: a-tojo@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

K.Y. and N.Y. contributed equally to this study.