Abstract

During recent years, our understanding of the pathogenesis of inherited microcytic anemias has gained from the identification of several genes and proteins involved in systemic and cellular iron metabolism and heme syntheses. Numerous case reports illustrate that the implementation of these novel molecular discoveries in clinical practice has increased our understanding of the presentation, diagnosis, and management of these diseases. Integration of these insights into daily clinical practice will reduce delays in establishing a proper diagnosis, invasive and/or costly diagnostic tests, and unnecessary or even detrimental treatments. To assist the clinician, we developed evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines on the management of rare microcytic anemias due to genetic disorders of iron metabolism and heme synthesis. These genetic disorders may present at all ages, and therefore these guidelines are relevant for pediatricians as well as clinicians who treat adults. This article summarizes these clinical practice guidelines and includes background on pathogenesis, conclusions, and recommendations and a diagnostic flowchart to facilitate using these guidelines in the clinical setting.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint providership of Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology.

Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For the CME questions, see page 4005.

Disclosures

Nancy Berliner, Editor, received grants for clinical research from GlaxoSmithKline. The authors and CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, declare no competing financial interest.

Learning objectives

Describe management of iron refractory iron-deficiency anemia resulting from defects in TMPRSS6, based on a review.

Describe management of hypotransferrinemia resulting from defects in TF.

Describe management of sideroblastic anemia resulting from defects in SLC25A38.

Release date: June 19, 2014; Expiration date: June 19, 2015

Introduction

Anemia in children, adolescents, and adults is commonly encountered in general clinical practice. There are multiple causes, but with a thorough history, physical examination, and limited laboratory evaluations, a specific diagnosis can often be established. A standard diagnostic approach is to classify anemia as microcytic (mean corpuscular volume [MCV] <80 fL), normocytic, or macrocytic (MCV >98 fL). Microcytic anemias are primarily caused by nutritional iron deficiency, iron loss resulting from gastrointestinal disease, iron malabsorption, hemoglobinopathies (including some thalassemia syndromes), and severe anemia resulting from chronic disease. Normocytic anemia can be caused by hemolysis, anemia resulting from chronic disease, or bone marrow pathology. Macrocytic anemias are often caused by toxic agents such as alcohol, folic acid and/or vitamin B12 deficiency or, less frequently, by myelodysplastic syndrome.

However, for some patients with microcytic anemias, the cause remains unexplained by the above-mentioned categorization. In these patients, elevation of ferritin and/or transferrin saturation (TSAT) or low TSAT in combination with low-normal ferritin levels (>20 µg/L) suggest a genetic disorder of iron metabolism or heme synthesis. Family history, an anemia that is refractory or incompletely responsive to iron supplementation, and features such as neurologic disease and skin photosensitivity may also be indicative of these disorders.

During recent years, defects in genes with roles in systemic and cellular iron metabolism and heme synthesis have been identified as being involved in the pathogenesis of these genetic anemias.1-4 We recommend integrating these clinical and molecular insights into daily practice to avoid unnecessary delay in diagnosis, invasive or costly diagnostic tests, and harmful treatments. Importantly, in some genetic anemias, such as the sideroblastic anemias, iron overload is of greater consequence than the anemia itself.3,5 Unrecognized tissue iron loading might lead to severe morbidity and even mortality, underscoring the need for accurate and timely diagnosis of these disorders.

In this article, we present evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of 12 disorders of microcytic anemia that result from defects in 13 different genes and that lead to genetic disorders of iron metabolism and heme synthesis. We included the disorder associated with a defect in SLC40A1 (ferroportin-1) in these guidelines because in animal models, mutations in this gene cause a microcytic anemia,6 and narrative reviews classified the related human anemia as microcytic,1 despite the fact that our literature review showed that microcytic anemia is rarely reported in these patients. We also included (normocytic) patients with X-linked dominant protoporphyria (XLDPP), because this disorder is a variant of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP), a disease in which patients present with microcytic anemia. We describe the methodology we used, provide a short and illustrated introduction to iron homeostasis (Figure 1),2,7 and briefly discuss pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. We present (1) case tables listing characteristics of the individual patients described in the literature (supplemental Data 1 on the Blood Web site), except for patients with loss-of-function (LOF) defects in ALAS2 and defects in SLC40A1, UROS, and FECH because of their relatively high prevalence; (2) evidence-based conclusions and related references (supplemental Data 2); (3) recommendations that include advice on family screening (Table 1)8,9 ; and (4) results of literature analysis on prevalence of anemia in patients with defects in SLC40A1 (supplemental Data 3). To help the clinician, we have included a table that summarizes the characteristics of the disorders (Table 2) and a flowchart (Figure 2) to aid in the diagnosis of the relevant diseases.

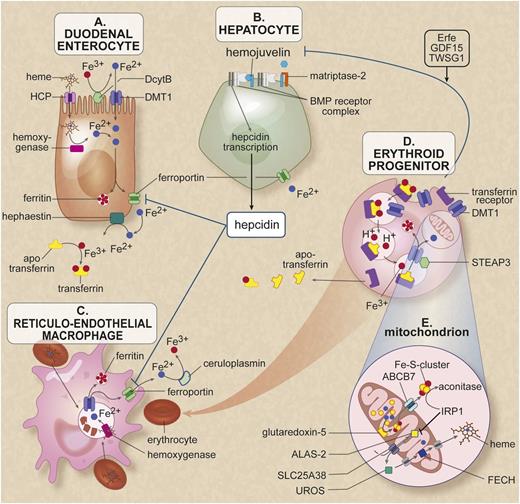

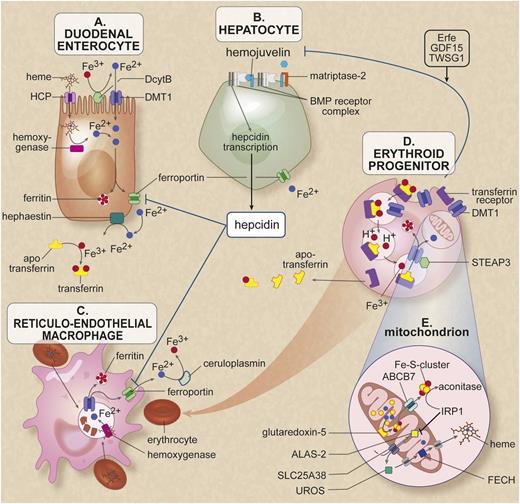

Cells and proteins involved in iron homeostasis and heme synthesis. (A) The enterocyte: iron enters the body through the diet. Most iron absorption takes place in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. The absorption of iron takes place in different phases. In the luminal phase, iron is solubilized and converted from trivalent iron into bivalent iron by duodenal cytochrome B (DcytB). Heme is released by enzymatic digestion of hemoglobin and myoglobin during the mucosal phase, iron is bound to the brush border and transported into the mucosal cell by the iron transporter divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). Heme enters the enterocyte presumably through the heme carrier protein (HCP). In the cellular phase, heme is degraded by heme oxygenase and iron is released. Iron is either stored in cellular ferritin or transported directly to a location opposite the mucosal side. In the last phase of iron absorption, Fe2+ is released into the portal circulation by the basolateral cellular exporter ferroportin. Enterocytic iron export requires hephaestin, a multicopper oxidase homologous to ceruloplasmin (CP), which oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+ for loading onto transferrin. This cellular efflux of iron is inhibited by the peptide hormone hepcidin binding to ferroportin and subsequent degradation of the ferroportin-hepcidin complex. (B) The hepatocyte serves as the main storage for the iron surplus (most body iron is present in erythrocytes and macrophages). Furthermore, this cell, as the main producer of hepcidin, largely controls systemic iron regulation. The signal transduction pathway runs from the membrane to the nucleus, where bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor, the membrane protein hemojuvelin (HJV), the hemochromatosis (HFE) protein, transferrin receptors 1 and 2, and matriptase-2 play an essential role. Through intracellular pathways, a signal is given to hepcidin transcription. The membrane-associated protease matriptase-2 (encoded by TMPRSS6) detects iron deficiency and blocks hepcidin transcription by cleaving HJV. (C) The macrophage belongs to the group of reticuloendothelial cells and breaks down senescent red blood cells. During this process, iron is released from heme proteins. This iron can either be stored in the macrophage as hemosiderin or ferritin or it may be delivered to the erythroid progenitor as an ingredient for new erythrocytes. The iron exporter ferroportin is responsible for the efflux of Fe2+ into the circulation. In both hepatocytes and macrophages, this transport requires the multicopper oxidase CP, which oxidases Fe2+ to Fe3+ for loading onto transferrin. (D) The erythroid progenitor: transferrin saturated with 2 iron molecules is endocytosed via the transferrin receptor 1. After endocytosis, the iron is released from transferrin, converted from Fe3+ to Fe2+ by the ferroreductase STEAP3, and transported to the cytosol by DMT1, where it is available mainly for the heme synthesis. Erythropoiesis has been reported to communicate with the hepatocyte by the proteins TWSG1, GDF15, and erythroferrone (Erfe) that inhibit signaling to hepcidin.7,14,30 (E) The mitochondria of the erythroid progenitor: in the mitochondria the heme synthesis and Fe-S cluster synthesis takes place. In the first rate-limiting step of heme synthesis, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is synthesized from glycine and succinyl-coenzyme A by the enzyme δ-ALA synthase 2 (ALAS2) in the mitochondrial matrix. The protein SLC25A38 is located in the mitochondrial membrane and is probably responsible for the import of glycine into the mitochondria and might also export ALA to the cytosol. In the heme synthesis pathway, the uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS) in the cytosol is the fourth enzyme. It is responsible for the conversion of hydroxymethylbilane (HMB) to uroporphyrinogen III, a physiologic precursor of heme. In the last step, ferrochelatase (FECH), located in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, is responsible for the incorporation of Fe2+ into PPIX to form heme. GATA1 is critical for normal erythropoiesis, globin gene expression, and megakaryocyte development; it also regulates expression of UROS and ALAS2 in erythroblasts. The enzyme glutaredoxin-5 (GLRX5) plays a role in the synthesis of the Fe-S clusters, which are transported to the cytoplasm, probably via the transporter ABCB7. Figure adapted from van Rooijen et al.2 Professional illustration created by Debra T. Dartez.

Cells and proteins involved in iron homeostasis and heme synthesis. (A) The enterocyte: iron enters the body through the diet. Most iron absorption takes place in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. The absorption of iron takes place in different phases. In the luminal phase, iron is solubilized and converted from trivalent iron into bivalent iron by duodenal cytochrome B (DcytB). Heme is released by enzymatic digestion of hemoglobin and myoglobin during the mucosal phase, iron is bound to the brush border and transported into the mucosal cell by the iron transporter divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). Heme enters the enterocyte presumably through the heme carrier protein (HCP). In the cellular phase, heme is degraded by heme oxygenase and iron is released. Iron is either stored in cellular ferritin or transported directly to a location opposite the mucosal side. In the last phase of iron absorption, Fe2+ is released into the portal circulation by the basolateral cellular exporter ferroportin. Enterocytic iron export requires hephaestin, a multicopper oxidase homologous to ceruloplasmin (CP), which oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+ for loading onto transferrin. This cellular efflux of iron is inhibited by the peptide hormone hepcidin binding to ferroportin and subsequent degradation of the ferroportin-hepcidin complex. (B) The hepatocyte serves as the main storage for the iron surplus (most body iron is present in erythrocytes and macrophages). Furthermore, this cell, as the main producer of hepcidin, largely controls systemic iron regulation. The signal transduction pathway runs from the membrane to the nucleus, where bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor, the membrane protein hemojuvelin (HJV), the hemochromatosis (HFE) protein, transferrin receptors 1 and 2, and matriptase-2 play an essential role. Through intracellular pathways, a signal is given to hepcidin transcription. The membrane-associated protease matriptase-2 (encoded by TMPRSS6) detects iron deficiency and blocks hepcidin transcription by cleaving HJV. (C) The macrophage belongs to the group of reticuloendothelial cells and breaks down senescent red blood cells. During this process, iron is released from heme proteins. This iron can either be stored in the macrophage as hemosiderin or ferritin or it may be delivered to the erythroid progenitor as an ingredient for new erythrocytes. The iron exporter ferroportin is responsible for the efflux of Fe2+ into the circulation. In both hepatocytes and macrophages, this transport requires the multicopper oxidase CP, which oxidases Fe2+ to Fe3+ for loading onto transferrin. (D) The erythroid progenitor: transferrin saturated with 2 iron molecules is endocytosed via the transferrin receptor 1. After endocytosis, the iron is released from transferrin, converted from Fe3+ to Fe2+ by the ferroreductase STEAP3, and transported to the cytosol by DMT1, where it is available mainly for the heme synthesis. Erythropoiesis has been reported to communicate with the hepatocyte by the proteins TWSG1, GDF15, and erythroferrone (Erfe) that inhibit signaling to hepcidin.7,14,30 (E) The mitochondria of the erythroid progenitor: in the mitochondria the heme synthesis and Fe-S cluster synthesis takes place. In the first rate-limiting step of heme synthesis, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is synthesized from glycine and succinyl-coenzyme A by the enzyme δ-ALA synthase 2 (ALAS2) in the mitochondrial matrix. The protein SLC25A38 is located in the mitochondrial membrane and is probably responsible for the import of glycine into the mitochondria and might also export ALA to the cytosol. In the heme synthesis pathway, the uroporphyrinogen III synthase (UROS) in the cytosol is the fourth enzyme. It is responsible for the conversion of hydroxymethylbilane (HMB) to uroporphyrinogen III, a physiologic precursor of heme. In the last step, ferrochelatase (FECH), located in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, is responsible for the incorporation of Fe2+ into PPIX to form heme. GATA1 is critical for normal erythropoiesis, globin gene expression, and megakaryocyte development; it also regulates expression of UROS and ALAS2 in erythroblasts. The enzyme glutaredoxin-5 (GLRX5) plays a role in the synthesis of the Fe-S clusters, which are transported to the cytoplasm, probably via the transporter ABCB7. Figure adapted from van Rooijen et al.2 Professional illustration created by Debra T. Dartez.

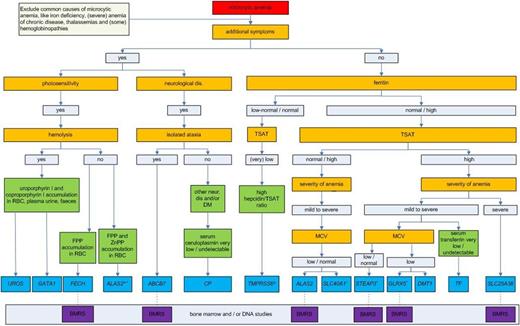

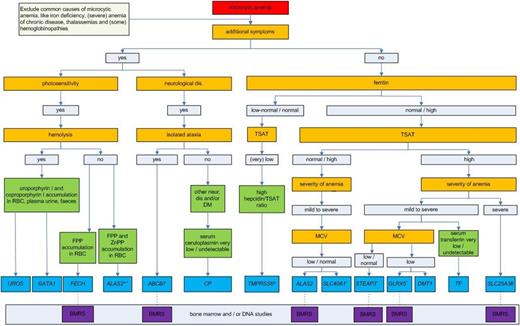

Diagnostic flowchart for microcytic anemias caused by inherited defects in iron metabolism or heme synthesis. Genes are given in italics and refer to the disorders of this review (Table 2). After clinical and laboratory assessment, clinicians may proceed to perform a diagnostic workup with either bone marrow smears or gene analysis. Iron parameters should be interpreted in the context of the age of the patient and the given treatment: older patients are more likely to have developed iron overload (increased TSAT and ferritin) due to increased and ineffective erythropoiesis and iron supplementation and transfusions. Note that for some diseases, the decision tree is based on only few patients (Table 2). BMRS, bone marrow ring sideroblasts; DM, diabetes mellitus; FPP, free protoporphyrin; neur. dis, neurologic disease; ZnPP, zinc protoporphyrin. *Patients have normocytic anemia and GOF mutation; +only 1 family described; ±patients have normocytic anemia and the majority have LOF mutations; ^in rare cases, these patients present with elevated ferritin levels.

Diagnostic flowchart for microcytic anemias caused by inherited defects in iron metabolism or heme synthesis. Genes are given in italics and refer to the disorders of this review (Table 2). After clinical and laboratory assessment, clinicians may proceed to perform a diagnostic workup with either bone marrow smears or gene analysis. Iron parameters should be interpreted in the context of the age of the patient and the given treatment: older patients are more likely to have developed iron overload (increased TSAT and ferritin) due to increased and ineffective erythropoiesis and iron supplementation and transfusions. Note that for some diseases, the decision tree is based on only few patients (Table 2). BMRS, bone marrow ring sideroblasts; DM, diabetes mellitus; FPP, free protoporphyrin; neur. dis, neurologic disease; ZnPP, zinc protoporphyrin. *Patients have normocytic anemia and GOF mutation; +only 1 family described; ±patients have normocytic anemia and the majority have LOF mutations; ^in rare cases, these patients present with elevated ferritin levels.

Methodology

These guidelines have been developed to assist clinicians and patients in the clinical decision-making process for rare anemias that are due to genetic disorders of iron metabolism and heme synthesis by describing a number of generally accepted approaches for the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders.

To develop these evidence-based guidelines, the working group adopted the methodology described in the Medical Specialist Guidelines 2.0 of the Netherlands Association of Medical Specialists.10 This methodology is based on the international Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II criteria for assessing the quality of guidelines (http://www.agreetrust.org).11 In short, the development of the guidelines began with the formulation of a number of starting questions (supplemental Data 4). Each question guided a systematic review of the literature in both MEDLINE and EMBASE up to December 2010, using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), free text words related to the name of the predefined genes and disease of interest (see “Definitions”), and disease-specific symptoms. In addition, we retrieved more recent original and review articles by using the same key words for searching PubMed, and checked the references of those articles. Searches were limited to those written in English, German, French, and Dutch. Searches were not limited by date.

The majority of the articles retrieved were case reports or small case series. The searches also showed a number of reviews; however, none of them used a systematic approach. Therefore, we modified the usual therapeutic/intervention-based system for grading the evidence12,13 of the conclusions in supplemental Data 2 into the following levels: (1) proven or very likely, based on results by numerous investigators in various populations and settings; (2) probable, based on a moderate number of reports; (3) indicative, based on a small number of reports; and (4) expert opinion of members of the working group.

Working group

The working group consisted of the authors of this article.

Definitions

These guidelines cover microcytic anemias due to genetic defects in iron metabolism or heme synthesis (Table 2). To select these diseases, we used recent reviews1,4 and added disorders that were described in more recent years (eg, sideroblastic anemia due to defects in STEAP3 and XLDPP). We excluded microcytic anemia caused by hemoglobinopathies and genetic diseases not predominantly characterized by a primary defect in iron metabolism or heme synthesis.

Introduction to iron metabolism and heme synthesis

Iron plays an essential role in many biochemical processes, particularly in the production of heme for incorporation into Hb and myoglobin, and Fe-S clusters, which serve as enzyme cofactors.14 In iron deficiency, cells lose their capacity for electron transport and energy metabolism. Clinically, iron deficiency causes anemia and may result in neurodevelopmental deficits.15 Conversely, iron excess leads to complications such as endocrine disorders, liver cirrhosis, and cardiac dysfunction.16

Therefore, tight regulation of body iron homeostasis on both systemic and cellular levels is paramount. These processes comprise several proteins, most of which have been discovered in the last 20 years. Defects in these proteins lead to disorders of iron metabolism and heme synthesis that are characterized by iron overload, iron deficiency, or iron maldistribution.

Cells involved in iron homeostasis are duodenal enterocytes, hepatocytes, macrophages, and erythroid precursors. To illustrate the description of pathophysiology for the different disorders, we schematically (Figure 1) present the function of the above-mentioned cells in iron homeostasis and the proteins involved.

1. Disorders due to low iron availability for erythropoiesis

1A. Iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) due to defects in TMPRSS6

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

TMPRSS6 (OMIM 609862) encodes matriptase-2 (a type II plasma membrane serine protease) that senses iron deficiency and blocks hepcidin transcription by cleaving HJV. Consequently, pathogenic TMPRSS6 defects result in uninhibited hepcidin production, causing IRIDA.17-19 At the population level, genome-wide association studies show that TMPRSS6 is polymorphic with a relatively large number of high-frequency polymorphisms, some of which (particularly p.Ala736Val) are associated with significant decrease in the concentrations of iron, Hb, and MCV of the red blood cell.20,21 The prevalence of pathogenic mutations leading to IRIDA is unknown, but underdiagnosis seems likely. Patients with IRIDA due to a suspected homozygous or compound heterozygous TMPRSS6 defect are described in 61 patients in 39 families. Because functional studies are not always performed, it is unclear whether all these mutations are pathogenic. A few patients with microcytic anemia, low TSAT, and low-normal ferritin are reported to be heterozygous for TMPRSS6 defects (supplemental Data 1).

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

Most patients with IRIDA present in childhood with a microcytic anemia (which tends to become less severe with increasing age22 ) in combination with a remarkably low TSAT and, if untreated, a low-to-normal ferritin. Most patients fail to respond to oral iron, but because this feature is also observed in iron-deficient anemic patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, or celiac disease, these (nongenetic) disorders should be considered in the diagnostic workup.23

In IRIDA, serum hepcidin is inappropriately high, given the low body iron status. Consequently, the hepcidin:TSAT ratio is high.24 In the absence of inflammation, an increased hepcidin:TSAT ratio is specific for IRIDA, whereas a low hepcidin:ferritin ratio is characteristic for many genetic iron loading disorders.

In affected children, growth, development, and intellectual performances are normal.25 Although the pedigree structure of most patients with IRIDA shows an autosomal recessive inheritance, anecdotal reports suggest that heterozygous pathogenic TMPRSS6 mutations might cause a mild IRIDA phenotype (supplemental Data 1). It is still unclear whether this can be explained by environmental factors, a combination with modulating polymorphisms, or a low-expressing allele, or whether the current Sanger sequencing strategy misses certain defects in the exons or introns of the gene or its regulatory regions or whether defects in other genes are involved. Therefore, we conclude that IRIDA due to a TMPRSS6 defect can be diagnosed with certainty only when the patient is homozygous or compound heterozygous for a pathogenic mutation.

Treatment.

Case reports indicate that the pathogenicity of the TMPRSS6 defect determines the response to oral iron. Severe TMPRSS6 defects usually lead to oral iron resistance. Only a few patients (partially) respond to oral iron (supplemental Data 1). Ascorbic acid (3 mg per day) supplementation along with oral ferrous sulfate has been reported to improve Hb and iron status in an infant resistant to oral iron supplementation only.26 Case series show that repeated administration of intravenous iron (iron sucrose or iron gluconate) increase Hb and ferritin and, to a lesser extent, MCV and TSAT, although complete normalization of Hb is seldom achieved. Attempting to correct the Hb level to the reference range may place the patient at risk for iron overload. We found no evidence for a threshold of circulating ferritin levels above which the iron in the reticuloendothelial macrophages becomes toxic in the long term. However, following guidelines for iron treatment in patients with chronic kidney disease,27 we recommend monitoring serum ferritin levels and not exceeding a concentration of 500 µg/L to avoid this risk, especially in children and adolescents. The role of EPO treatment in IRIDA is controversial.28,29 Trials with novel hepcidin-lowering compounds in these patients have not been performed.30

1B. Ferroportin disease due defects in SLC40A1

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

SLC40A1 (ferroportin-1, IREG1, MTP1, SLC11A3) (OMIM 606069) encodes the protein ferroportin,31 the only known human cellular iron exporter (Figure 1).14,32

In 2000, ferroportin was identified in the zebrafish mutant weissherbst as the defective gene responsible for the hypochromic anemia in these animals that was ascribed to inadequate circulatory iron levels.6 In humans, only heterozygous mutations in SLC40A1 are reported, and microcytosis is not observed. The resulting hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) type 4, or ferroportin disease, is an autosomal dominant condition with a heterogeneous phenotype and is primarily characterized by iron overload.33,34 In almost all case series and the available narrative reviews, mutations causing ferroportin disease are classified into two groups: LOF (HH type 4A or classical HH) and GOF (HH type 4B or atypical HH) mutations.35,36 Functional studies and clinical data show that an LOF mutation typically leads to iron retention in the duodenal cells and macrophages due to reduced ferroportin activity and preserved inhibitory capacity of hepcidin. The phenotype is characterized by an elevated serum ferritin level in association with a low-to-normal TSAT and predominant iron deposition in macrophages; some patients have a low tolerance to phlebotomy.35 GOF mutations lead to increased iron absorption due to increased ferroportin activity, which is resistant to the inhibitory effect of hepcidin. As a consequence, the iron overload phenotype of these patients is indistinguishable from other forms of hereditary HH33,34 ; therefore, this subtype of ferroportin disease does not fit into the category of “disorders due to low iron available for erythropoiesis.”

For certain genotypes, however, the functional studies and the biochemical and histologic phenotypes vary among studies and patients.37 Thus, the distinction between LOF and GOF mutations is not always straightforward. To define the type of mutation for the purposes of these guidelines, we developed a classification system based on both phenotypic and functional characteristics (supplemental Data 3). On the basis of this classification, we identified 36 different LOF mutations and 15 GOF mutations. A total of 207 patients with an LOF mutation and 73 patients with a GOF mutation were found worldwide.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

Symptoms are related to iron overload and are nonspecific. Because these guidelines cover anemias, in our evaluation of the literature on ferroportin disease, we investigated the occurrence of anemia (defined by the World Health Organization)38 as the presenting symptom.

In 76 (27.7%) and 24 (8.5%) of 280 patients, both Hb and MCV were numerically noted. Eight of the patients (10%) fulfilled the WHO criteria of anemia without additional causes of microcytic anemia (Table 1 in supplemental Data 3). Five males had Hb between 12.0 and 12.9 g/dL, and three females had Hb between 11.1 and 11.5 g/dL without microcytosis. Seven of the 8 anemic patients were annotated with an LOF mutation.

We conclude that of all 76 patients diagnosed with iron overload due to both LOF and GOF mutations in SLC40A1 and with documented Hb levels, only ∼10% were anemic. This anemia is described as mild and normocytic.

Treatment.

Iron overload in patients with both LOF and GOF ferroportin disease is treated with phlebotomy. Both the application of phlebotomy and its effects were described for 94 patients. In 14 (14.8%) of the 94 patients, a transient mild or profound anemia during phlebotomy treatment was reported. Our literature evaluation showed that the risk for the development of anemia during phlebotomy was associated with older age and an LOF mutation phenotype (eg, a relatively low TSAT) (Table 2 in supplemental Data 3). Data from case reports suggest that patients who develop anemia upon phlebotomy benefit from extension of the phlebotomy interval.

1C. Aceruloplasminemia (ACP) due to defects in CP

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

CP (OMIM 604290) encodes CP, which is secreted into plasma and carries 95% of circulating plasma copper. CP catalyzes cellular efflux of iron by oxidizing Fe2+ to Fe3+ for binding to circulating transferrin (Figure 1).39 In vitro studies and studies with mice show that CP is also required for the stability of the iron exporter ferroportin, especially in glial cells.40 Mouse studies demonstrate that the absence of CP leads to widespread iron overload in parenchymal and reticuloendothelial organs, including the nervous system.39

The incidence of ACP in Japan is estimated to be approximately 1 per 2 000 000 in nonconsanguineous marriages. There are no reliable data on the incidence and prevalence in Western European countries.41 In total, 35 pathogenic CP mutations have been described in 50 families. ACP is a rare autosomal recessive disease. However, 7 patients with a clinical phenotype of ACP were heterozygous for a CP defect (supplemental Data 1).

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

Iron accumulation in ACP affects the liver, pancreas, and central nervous system.42 Patients with ACP develop the classical triad of DM, retinal degeneration, and neurodegenerative disease with extrapyramidal and cerebellar symptoms in combination with mental dysfunction. A mild normocytic to microcytic anemia with low serum iron and elevated serum ferritin is a constant feature in ACP.43 However, anemia was not the presenting symptom in any of the described patients. Disease onset typically occurs in the fourth to fifth decade of life with neurodegenerative symptoms. Most patients die in the sixth decade of life as a result of neurologic complications.42 Despite the hepatic iron overload, ACP has not been described to be associated with liver disease.

Absent or very low serum CP in combination with low serum copper and iron, high serum ferritin, and increased hepatic iron concentration is indicative of ACP. The diagnosis is supported by characteristic findings on MRI that are compatible with iron accumulation in liver, pancreas, and brain. Homozygous or compound heterozygous CP defects confirm the diagnosis of ACP.

Treatment.

Case series describe normalization of serum ferritin and decrease of hepatic iron overload after treatment with iron chelation.42 In 6 patients, neurologic improvement,42-45 and in 2 other patients, reduction of insulin demand were described on treatment with iron chelators.46

Oral administration of zinc sulfate in a symptomatic heterozygous patient with ACP has been reported, but the effect on neurologic symptoms remains unclear.44,47 Three homozygous patients with ACP were treated with fresh frozen plasma; their outcome was not reported.48-50

The anemia in ACP is mild and does not need any intervention.

2. Disorders due to defects in iron acquisition by the erythroid precursors

2A. Hypotransferrinemia due to defects in TF

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

Genetic hypotransferrinemia is a rare autosomal recessive disease due to a defect in TF (OMIM 19000).51 Transferrin deficiency leads to low concentrations of transferrin-bound iron with iron-deficient erythropoiesis and high concentrations of non–transferrin-bound iron with subsequent iron overload in nonhematopoietic tissues. Functional studies in a limited number of patients indicate that intestinal iron absorption is increased with augmented plasma iron clearance and reduced red cell iron utilization.52,53 The increased intestinal iron absorption results from the strongly reduced hepatic hepcidin production ascribed to iron-deficient erythropoiesis and low transferrin concentration.54,55

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

Patients present in early life with microcytic and hypochromic anemia. The anemia is characterized by low serum iron and high ferritin levels. The transferrin level varies from being below limits of detection to being 20% of normal and is fully saturated. Serum hepcidin levels are low. The iron content in the bone marrow is reduced with a decreased myeloid:erythroid ratio in most patients.52,53,56-59

Affected children may show a failure to thrive with occasional retardation in mental development. There are signs of widespread iron overload with hepatomegaly and strikingly early endocrinopathy, skin iron deposition, and sometimes fatal cardiomyopathy. Some patients have osteoporosis.58,59

The diagnosis is confirmed by molecular analysis of TF. Heterozygous relatives have decreased transferrin concentrations without anemia or systemic iron loading.

Treatment.

Treatment consists of infusions of apotransferrin either directly or as plasma. Data on the dosage and frequency of these infusions are limited. Monthly infusions of plasma have been reported to be sufficient to normalize Hb and serum ferritin levels. To date, only 3 patients have been treated with apotransferrin on a compassionate use basis.53,58 The calculated elimination half-life varied between 4.8 and 10 days. Apotransferrin is not on the market for clinical purposes, but it has an orphan drug status (orphan designation EU/3/12/1027 on 17 July 2012 by the European Medicines Agency). A clinical trial in patients with hypotransferrinemia is ongoing (NCT01797055). Reluctance with repeated erythrocyte transfusion or iron substitution is advocated to avoid further iron overload.

2B. Anemia with systemic iron loading due to defects in SLC11A2 (DMT1)

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

Molecular studies indicate that defects in SLC11A2 cause defective enterocyte and erythroid iron uptake.62 Systemic iron loading suggests the presence of an additional pathway for intestinal iron absorption (eg, as heme).63 Another explanation might be the low hepcidin levels, resulting in increased dietary iron absorption in case SLC11A2 is not completely eliminated.64 Anemia with systemic iron loading due to defects in SLC11A2 is a rare autosomal recessive disorder: 7 patients from 6 families have been described as having homozygous (n = 2) or compound heterozygous (n = 5) defects.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

Four of 7 described patients presented at birth with microcytic anemia and increased TSAT. Serum ferritin levels varied from low to moderately increased, with some association with erythrocyte transfusions or intravenous iron supplementation. Liver iron loading was demonstrated by MRI or biopsy in 5 of 7 patients at ages between 5 and 27 years, despite normal or only mildly increased ferritin concentrations in 3 of them.

Treatment.

The 7 described patients with severe anemia were treated with erythrocyte transfusions. Three patients received oral iron, which increased Hb and led to transfusion independency in one patient.

Three patients received EPO, resulting in an increase of Hb but, based on the clinical course of 1 patient, not in prevention of liver iron loading.65 Erythrocyte transfusions and probably also oral or intravenous iron cause additional liver iron loading. Chelation was not effective in reducing liver iron and resulted in a decrease of Hb (unpublished data, Tchernia and Beaumont).1,65

2C. Sideroblastic anemia due to defects in STEAP3

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

STEAP3 (OMIM 609671) encodes a ferroreductase, which is responsible for the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ in the endosomes of erythroblasts (Figure 1).66 Mouse studies show that absence of or reduced activity of ferroreductase results in severe microcytic anemia, which can be corrected by introduction of a functional STEAP3.67 The first and so far only human STEAP3 mutation was recently described in 3 siblings born to healthy, nonconsanguineous parents.68

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

The 3 siblings displayed a transfusion-dependent severe hypochromic anemia with a normal to slightly decreased MCV. Serum iron and ferritin were normal to increased, whereas TSAT was markedly increased. A bone marrow smear in the index patient showed ring sideroblasts. Liver biopsy after multiple erythrocyte transfusions showed iron loading. All patients suffered from gonadal dysfunction, as described for STEAP3-deficient mice.67,68 A heterozygous nonsense STEAP3 mutation was inherited from the father, but no defect was found in the mother. The authors explained the normal phenotype of the father by the STEAP3 expression of the “healthy” allele in lymphocytes, which was significantly higher than in his affected children.

Treatment.

Treatment consisted of a combination of erythrocyte transfusions and chelation, and EPO increased the transfusion interval.

3. Disorders due to defects in the heme and/or Fe-S cluster synthesis

3A. Sideroblastic anemia due to defects in SLC25A38

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

SLC25A38 (OMIM 610819) encodes a protein on the inner membrane of the mitochondria of hematopoietic cells, especially erythroblasts, and is essential for heme synthesis (Figure 1).69 Its specific function is not known, but it has been hypothesized that SLC25A38 facilitates 5-ALA production by importing glycine into mitochondria or by exchanging glycine for ALA across the mitochondrial inner membrane.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

Patients present with severe, often transfusion-dependent microcytic hypochromic anemia in childhood, which is clinically similar to thalassemia major. Bone marrow smears show ring sideroblasts. Serum ferritin levels and TSAT are increased, even before treatment with erythrocyte transfusions.

Treatment.

Symptomatic treatment consists of erythrocyte transfusions and iron chelation. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the only curative treatment; it was performed in 8 of 29 patients and resulted in disease-free survival in 4 patients (follow-up <5 years) (supplemental Data 1).

3B. XLSA with ataxia due to defects in ABCB7

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

ABCB7 (OMIM 300135) on the X-chromosome encodes a protein in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, which is the putative mitochondrial exporter of Fe-S complexes (Figure 1).3,71 Defects in ABCB7 result in disrupted iron metabolism and heme synthesis causing a mild, slightly microcytic, sideroblastic anemia and also cerebellar ataxia.72 Sideroblastic anemia with ataxia due to defects in ABCB7 is a rare, X-linked disease.72 Seventeen patients with 4 different pathogenic ABCB7 defects have been described in case reports, of which 5 were female, which might be explained by skewed X-inactivation. None of the women showed neurologic defects. There is no apparent genotype-phenotype correlation.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

The presenting symptom in all male patients was cerebellar ataxia that developed in childhood. Cerebral MRI showed cerebellar hypoplasia in 4 patients. Mild, slightly microcytic sideroblastic anemia was found, usually in the second decade of life. In 10 patients, free erythrocyte protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) was increased. None of the patients showed systemic iron loading.

Treatment.

Treatment of the mild anemia was not reported.

3C. XLSA due to defects in ALAS2

Pathophysiology and epidemiology.

ALAS2 (OMIM 301300) is located on chromosome X and encodes for ALA synthase 2 (ALAS2), an erythroid-specific isoform of the catalytic enzyme involved in heme synthesis in the mitochondria (Figure 1).73

Almost all ALAS2 defects are missense mutations, most commonly in domains important for catalysis or pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6) cofactor binding.74 Defects in the binding site of the transcription factor GATA1 in the first intron of ALAS2 have also recently been described.75

ALAS2 defects result in decreased protoporphyrin synthesis and subsequent reduced iron incorporation and heme synthesis, causing microcytic anemia and erythroid mitochondrial iron loading. Mitochondrial iron loading exacerbates the anemia through decreased pyridoxine sensitivity.76 Heme deficiency is associated with ineffective erythropoiesis, followed by increased intestinal iron uptake and tissue iron accumulation. XLSA is the most common genetic form of sideroblastic anemia.3 Since Cooley described the first patients with XLSA in 1945,77 61 different pathogenic ALAS2 defects have been described in 120 nonrelated families.78,79 As in most X-linked disorders, most female carriers of XLSA are asymptomatic. However, women with ALAS2 mutations may be affected because of skewed X-inactivation.80 Furthermore, physiologic age-related skewed X-inactivation in hematopoietic stem cells may play a role in the development of XLSA in female carriers with increasing age.81 Estimates on the prevalence of ALAS2 defects are not available. Since the phenotype might be mild, underdiagnosis is likely.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

XLSA is characterized by mild hypochromic, microcytic sideroblastic anemia in combination with systemic iron overload.3 Elevated red cell distribution width has been described in female carriers of the mutation and is ascribed to the presence of 2 erythrocyte populations.82 Phenotypic expression of XLSA is highly variable, even in patients with identical mutations.83 Case reports indicate that affected males generally present with symptoms of anemia in the first 2 decades of life or later with either manifestations of anemia or those of parenchymal iron overload. Manifestation among the elderly due to an acquired pyridoxine deficiency is described.84

Treatment.

The available evidence indicates that initial doses of oral vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) 50 to 200 mg per day are effective in improving anemia and iron overload in all responsive patients with XLSA.85 Occasionally, high doses may be considered. Once a response is obtained, evidence suggests that the life-long maintenance dose may be lowered to 10 to 100 mg per day, because doses that are too high may result in neurotoxicity.86

Because iron overload may compromise mitochondrial function and hence heme biosynthesis, patients with XLSA should not be considered pyridoxine refractory until iron stores are normalized.76 Most patients can be treated with phlebotomy for iron overload, because the anemia is mild. Hb typically increases, rather than decreases, after reversal of iron overload by phlebotomy.76

3D. Sideroblastic anemia due to defects in GLRX5

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

GLRX5 (OMIM 6095588) encodes for the mitochondrial disulfide glutaredoxin-5 (GLRX5), which is highly expressed in early erythroid cells and is essential for the biosynthesis of Fe-S clusters (Figure 1).

In vitro data show that in GLRX5-deficient erythroblasts, Fe-S cluster production is decreased, and more active iron-responsive protein 1 (IRP1) is present in the cytosol. This reflects a low-iron state of the cell and causes repression of target genes, including ALAS2, resulting in reduced heme synthesis, mitochondrial iron accumulation, and increased turnover of ferrochelatase.87,88 Sideroblastic anemia due to defects in GLRX5 is a rare autosomal recessive disease: only 1 male patient has been described.89

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

The patient, born from consanguineous parents, presented at age 44 years with type 2 DM and at 60 years with icterus and hepatosplenomegaly. There was a progressive microcytic anemia with increased TSAT, serum ferritin, and iron accumulation in both bone marrow macrophages and erythroblast mitochondria.

Treatment.

Treatment with iron chelation and erythrocyte transfusion resulted in an increase of Hb and a decrease in serum ferritin. Pyridoxine supplementation was not effective.

3E. EPP due to defects in FECH and GOF mutations in ALAS2(XLDPP)

Pathophysiology and epidemiology.

EPP comprises 2 variants, EPP and XLDPP, and belongs to the cutaneous porphyrias characterized by accumulation of free PPIX. Autosomal recessive EPP (OMIM 177000) is caused by defects in FECH (OMIM 612386), encoding for ferrochelatase in the mitochondria, which is responsible for iron insertion into PPIX to form heme (Figure 1).90 The prevalence differs worldwide and mode of inheritance is complex.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

The variants EPP and XLDPP are clinically indistinguishable. The predominant clinical presentation is painful photosensitivity, erythema, and stinging and burning of sunlight-exposed skin beginning in childhood. In patients with severe symptoms, the liver is affected.94 Twenty to 60% of the patients show a microcytic anemia, with a mean decrease in Hb in adult male patients of 1.2 g/dL and reduced iron stores.92

Fluorescent erythrocytes can be seen in a fresh, unstained blood smear. FPP is found in plasma and erythrocytes. ZnPP is typically increased in XLDPP due to the relative iron deficiency for the amount of PPIX.94

Treatment.

Since anemia is mild, its treatment is not warranted.94 Therapy for EPP is focused on minimizing the harmful effects of exposure to sunlight and on managing the hepatotoxic effects of protoporphyrin.

3F. CEP due to defects in UROS or GATA1

Pathogenesis and epidemiology.

UROS (OMIM 606938) encodes uroporphyrinogen III synthase, the fourth enzyme of the heme biosynthetic pathway. CEP (OMIM 263700) is a rare autosomal genetic disease caused by defects in UROS, leading to erythroid accumulation of nonphysiologic uroporphyrin I and coproporphyrin I.94 Reduced red cell survival due to excess porphyrin in erythrocytes contributes to hemolytic anemia found in most patients with CEP.95 To date, approximately 45 UROS mutations have been described in >200 individuals.96 An X-linked variant of CEP (OMIM 314050) caused by a mutation in GATA1 (OMIM 305371) on the X-chromosome has been reported for 1 patient.97 GATA1 regulates expression of UROS in erythroblasts.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis.

CEP typically presents with passage of red urine shortly after birth. Lifelong bullous cutaneous photosensitivity to visible light starts in early infancy, leading to scarring with photomutilation.94 Other manifestations include hypertrichosis, erythrodontia, osteoporosis, and corneal ulceration with scarring. Age of onset and severity of CEP are both highly variable.98 In a retrospective study of 29 CEP patients, 66% suffered from chronic hemolytic anemia with variable severity.98 Iron parameters are not described in these patients.

The patient with CEP caused by the GATA1 defect had a severe hypochromic microcytic hemolytic anemia mimicking the phenotype of thalassemia intermedia, in combination with thrombocytopenia.97 Biochemically, CEP patients have uroporphyrin and coprophorphyrin accumulation in erythrocytes, plasma, urine, and feces and decreased UROS activity in erythrocytes.94

Treatment.

Conclusions

We have provided clinical guidelines on orphan diseases, of which many aspects are still unknown. Consequently, the level of evidence for the management of these disorders is relatively low. We therefore recommend that centers of excellence that have expertise with these diseases join forces to identify new mechanisms, biomarkers, and treatments and to optimize management of patients with these diseases. Until more evidence is available, these guidelines can be used to assist clinicians and patients in their understanding, diagnosis, and management of microcytic genetic anemias of iron metabolism or heme synthesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Wessels, literature specialist, for her help in the systematic literature review of the various databases.

This work was supported by a grant from the Quality Foundation Funds Medical Specialists of The Netherlands Association of Medical Specialists, project number 7387043.

Authorship

Contribution: A.E.D., R.A.P.R., P.P.T.B., N.D., L.T.V., N.V.A.M.K., R.T., and D.W.S. were members of the working group, made literature and case tables, drafted, discussed, and finalized the guidelines, and edited the manuscript; T.v.B. served as advisor and provided support in the use of the methodology for guideline development; and D.W.S. initiated and coordinated the project and acquired funding. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.W.S. is medical director of the www.hepcidinanalysis.com initiative that serves the scientific and medical community with hepcidin measurements on a fee-for-service basis. She is an employee of the Radboud University Medical Centre, which offers genetic testing for the genes described in the current guideline (http://www.umcn.nl/Informatievoorverwijzers/Genoomdiagnostiek/en/Pages/default.aspx). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dorine W. Swinkels, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Laboratory of Genetic, Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases (830), Radboud University Medical Center, PO Box 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands; e-mail: Dorine.Swinkels@radboudumc.nl.