Key Points

MYC translocations represent a genetic subgroup of NOTCH1-independent T-ALL clustered within the TAL/LMO category.

MYC translocations are secondary abnormalities, which appear to be associated with induction failure and relapse.

Abstract

MYC translocations represent a genetic subtype of T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), which occurs at an incidence of ∼6%, assessed within a cohort of 196 T-ALL patients (64 adults and 132 children). The translocations were of 2 types; those rearranged with the T-cell receptor loci and those with other partners. MYC translocations were significantly associated with the TAL/LMO subtype of T-ALL (P = .018) and trisomies 6 (P < .001) and 7 (P < .001). Within the TAL/LMO subtype, gene expression profiling identified 148 differentially expressed genes between patients with and without MYC translocations; specifically, 77 were upregulated and 71 downregulated in those with MYC translocations. The poor prognostic marker, CD44, was among the upregulated genes. MYC translocations occurred as secondary abnormalities, present in subclones in one-half of the cases. Longitudinal studies indicated an association with induction failure and relapse.

Introduction

MYC is one of the main phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT targets, thus rearrangements underlying PI3K/AKT activation result in MYC overexpression. Deregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway plays a pivotal role in T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), being constitutively activated in cases with NOTCH1/FBXW7 (50%-60%) mutations, PTEN (10%-30%) inactivation and PTPN2 (6%) deletions.1-4 These observations have identified MYC as a key T-ALL oncogene and an effective therapeutic target.5 The potential role of MYC activation in initiating T-ALL tumorigenesis has been demonstrated in transgenic zebrafish and mouse models, where the induced overexpression of c-Myc lead to T-ALL development with high penetrance and short latency.5-8 Moreover, in T-ALL murine models, c-Myc appeared to be critical for leukemia initiation, maintenance, and self-renewal, as its suppression, prevents leukemia development.9-11

We have characterized an emerging group of T-ALL with MYC translocations, identified as a specific subgroup of NOTCH1-independent TAL/LMO-positive leukemia, occurring in about 6% of adult and childhood T-ALL.

Study design

To assess the incidence of MYC translocations in T-ALL, we investigated 64 adults and 132 children (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site). Combined interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (CI-FISH) and/or Predictive Analysis of Microarrays12 classified 80% of cases into groups according to distinct genetic features: TAL/LMO (57), HOXA (49), TLX3 (31), TLX1 (16), and NKX2-1 (5), whose distribution into age groups reflected previous studies (supplemental Table 1). Karyotyping, CI-FISH, single nucleotide polymorphism array, and mutational analysis investigated concurrent genomic abnormalities (supplemental Methods).12

Results and discussion

Incidence and type of MYC translocations

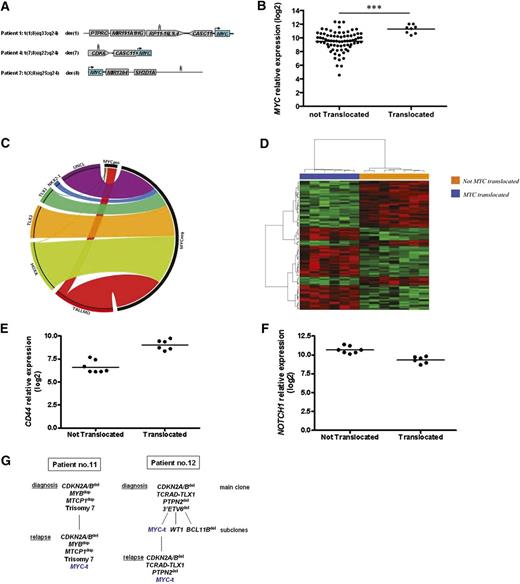

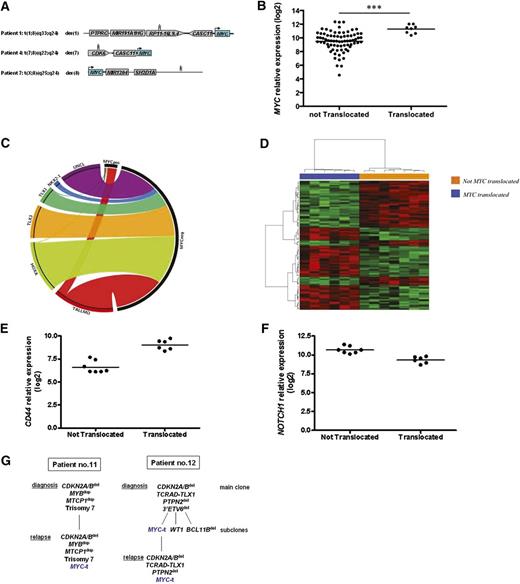

MYC translocations were detected in 12 of 196 cases of T-ALL (6.1%) and were equally distributed between children and adults (Table 1). They involved T-cell receptor (TCR) loci in 6 cases and new partners in the other 6. The 8q24 breakpoints clustered within the telomeric region of MYC in all TCR translocations, whereas in the non-TCR translocations the 8q24 breakpoints mapped both telomeric and centromeric to MYC (supplemental Figure 1) mirroring non-IGH MYC translocations in B-cell ALL.13

Here, non-TCR translocation partners were assessed in 4 cases. CDK6/7q21.2, rearranged in T-ALL with t(5;7)(q35;q21) and TLX3 overexpression,14 was involved in cases 3 and 4. Hitherto-undescribed breakpoints involved 1q32.1, in case 1, within a long intergenic noncoding RNA, about 300 kb downstream of PTPRC and Xq25, in case 7, in a no-gene region 5 kb upstream of SH2D1 (supplemental Figure 2). Whatever the partner, MYC translocations resulted in MYC overexpression (Figure 1B). Remarkably, common to all cases was MYC relocation close to genes which are transcriptionally active in T lymphocytes (supplemental Figure 2).

(A) Non-TCR partners of 3 cases of T-ALL (nos. 1, 4, and 7 from Table 1) with MYC translocations. Mapping of superenhancers at 1q32, 7q21, and Xq25 were indicated with 3 vertical thin bars. (B) MYC expression in 83 cases of pediatric T-ALL and in 8 MYC translocation–positive T-ALL (nos. 1-4, 9-12 from Table 1). Cases with translocations had a significantly higher MYC expression. (C) Circos plot shows distribution of MYC translocations according to genetic categories. MYC translocation–positive T-ALL clustered into the TAL/LMO category; (D) Supervised gene expression profiling analysis of 13 TAL/LMO-positive T-ALL with high MYC expression at diagnosis (Q4): 6 cases with MYC translocations (nos. 1-4, 9, 10; Table 1) clustered together and separated from the 7 cases without. (E) Q4 TAL/LMO-positive T-ALL: CD44 expression was higher in T-ALL cases with MYC translocation compared with cases without. (F) NOTCH1 expression was significantly lower in cases with MYC translocations compared with cases without. (G) Longitudinal FISH studies in 2 cases: in case no. 11 the clone with MYC translocation was not detected at diagnosis but only at relapse (left); in case no. 12, the small subclone (∼8%) with the MYC translocation present at diagnosis was found in 100% of leukemic blasts at relapse. Q4, fourth quartile.

(A) Non-TCR partners of 3 cases of T-ALL (nos. 1, 4, and 7 from Table 1) with MYC translocations. Mapping of superenhancers at 1q32, 7q21, and Xq25 were indicated with 3 vertical thin bars. (B) MYC expression in 83 cases of pediatric T-ALL and in 8 MYC translocation–positive T-ALL (nos. 1-4, 9-12 from Table 1). Cases with translocations had a significantly higher MYC expression. (C) Circos plot shows distribution of MYC translocations according to genetic categories. MYC translocation–positive T-ALL clustered into the TAL/LMO category; (D) Supervised gene expression profiling analysis of 13 TAL/LMO-positive T-ALL with high MYC expression at diagnosis (Q4): 6 cases with MYC translocations (nos. 1-4, 9, 10; Table 1) clustered together and separated from the 7 cases without. (E) Q4 TAL/LMO-positive T-ALL: CD44 expression was higher in T-ALL cases with MYC translocation compared with cases without. (F) NOTCH1 expression was significantly lower in cases with MYC translocations compared with cases without. (G) Longitudinal FISH studies in 2 cases: in case no. 11 the clone with MYC translocation was not detected at diagnosis but only at relapse (left); in case no. 12, the small subclone (∼8%) with the MYC translocation present at diagnosis was found in 100% of leukemic blasts at relapse. Q4, fourth quartile.

In T-ALL, high MYC expression is mainly caused by molecular mechanisms acting at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level.15 In this study, we have shown that other genes/regions besides TCR may be involved in MYC translocations and that the incidence of MYC translocations in T-ALL is higher than previously reported.

Genetic profile of T-ALL with MYC translocations

Similar to other type B abnormalities, MYC translocations were not seen as isolated changes. In-depth molecular-cytogenetic characterization revealed from 2 to 9 abnormalities per case (median, 3.7) (Table 1; supplemental Table 2). T-ALL with MYC translocations clustered within the TAL/LMO category (Pearson χ2, P = .018) (Figure 1C). Complete or partial trisomies of chromosomes 6 (3 of 12, 25%) (χ2, P < 0,001) and 7 (3 of 12, 25%) (χ2, P < .001) were significantly associated with MYC translocations and occurred together in all cases (2, 7, and 11 from Table 1). Other cooccurring abnormalities were CDKN2A/B deletions (CDKN2ABdel) (75%) and PTEN inactivation, resulting from deletion or mutation (PTENdel/mut) (58%). Similar results were found in the MOLT-16 and SKW-3/KE-37 cell lines with t(8;14)(q24;q11)/TCRAD-MYC. In fact, they both carry SIL-TAL1 and/or LMO2 translocations as primary abnormalities, and CDKN2ABdel and PTENdel/mut as additional hits (supplemental Table 3). PTEN inactivation in primary samples as well as cell lines reflect results from experimental mouse models, which have shown that c-Myc rearrangements and Ptendel exert a synergistic effect in the development of T-ALL, appearing to replace the function of Notch1.8,16 Interestingly, PTENdel/mut and NOTCH1 mutations were mutually exclusive in our cases, confirming that they arise in different T-ALL subgroups.17 In a unique TLX1-positive case (no. 12), the MYC translocation was associated with PTPN2 loss. The 2 PTEN- and PTPN2-negative regulators of PI3K/AKT signaling18 were inactive in ∼65% of our cases, suggesting that constitutive PI3K/AKT pathway activation is a critical synergistic hit in this T-ALL subgroup.

MYC translocations identify a subgroup within the TAL/LMO category

Within the set of 51 pediatric patients with TAL/LMO-positive T-ALL, the 6 with MYC translocations belonged to the group with the highest MYC expression, defined as the fourth quartile (Q4) based on MYC expression. Supervised gene expression profiling analysis of the Q4 group showed that patients with and those without MYC translocations clustered separately (Figure 1D). A Shrinkage t test revealed 148 genes differently expressed between the 2 groups (supplemental Table 4). Namely, 77 were significantly upregulated and 71 genes downregulated (local false discovery rate <0.05) in the group with MYC translocations compared with the group without. Specifically, a >1.3-fold change in CD44 expression was observed in patients with MYC translocations, whereas NOTCH1 and genes associated with NOTCH1 activation (PTCRA, NOTCH3, HES4, and CR2) were significantly downregulated (Figure 1E-F). In support of these results, gene set enrichment analysis confirmed enrichment of genes in the NOTCH1 pathway in the group without MYC translocations (q value = 0.06; NES, 1.71) (supplemental Figures 3 and 4A). Gene set enrichment analysis further indicated significant enrichment of cell death and apoptosis pathway genes in patients harboring MYC translocations (supplemental Figure 4B-C).

MYC-positive subclones are associated with relapse/induction failure

In case 12 (Table 1), paired diagnostic and relapse bone marrow samples showed that the size of the subclone with MYC translocations increased at relapse, rising from 8% to 100%, whereas other abnormalities, which were present either in the main clone, that is, ETV6del, or in diverse subclones, such as WT1del and BCL11Bdel, disappeared at relapse (Figure 1G). These findings are in line with results from xenograft models19 which showed that MYC confers a proliferative advantage and resistance to drug toxicity. It is noteworthy that in mice c-Myc plays a crucial role in maintenance and self-renewal of leukemia-initiating cells, which are thought to be resistant to chemotherapy and mediate relapse.11 In case 11, the MYC translocation, present at relapse, was not detected at diagnosis, implicating that it was acquired during disease progression (Figure 1G). Taken together, these data suggest that identification and possible eradication of small MYC-positive subclones at diagnosis and/or during the early stages of treatment may assist in prevention of disease progression. Notably, MYC translocations were found in subclones of variable size (range, 8%-62%) in 4 additional cases (Table 1).

Clinical and hematologic characteristic of T-ALL with MYC translocations

MYC translocation–positive T-ALL is characterized by leukocytosis and cortical/mature differentiation arrest in the majority of cases. It was not possible to evaluate the prognostic implications of MYC translocations in this retrospective study including children and adults belonging to different treatment protocols. However, poor prognostic markers, such as high CD44 expression and PTEN inactivation, appeared to be strongly associated with this leukemia subgroup.20-23 Moreover, although determination of minimal residual disease, the most powerful criteria used for risk stratification of pediatric ALL, classified case 2 into the standard-risk group, this patient failed induction therapy and died in disease. Similar to B-lineage ALL and acute myeloid leukemia,24,25 in which disease relapse has been related to minor leukemic subclones rather than to the predominant clone at diagnosis, subclones with MYC translocations in T-ALL may be more resistant to therapy and thus sustain relapse.

The microarray data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE60733).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Francesca Grillo and Maddalena Paganin for mutational analysis in selected patients belonging to the Associazione Italiana Emato-Oncologia Pediatrica (AIEOP) protocol, Dr Giovanni Roti for providing cell lines, and Drs Renato Bassan and Cristina Morerio for providing biological samples.

C. Mecucci is supported by Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base (FIRB 2011 RBAP11TF7Z_005), Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC IG 11512), and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia (Cod. 2012.0108.021 Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica). G.t.K. is supported by Fondazione Cariparo Progetto d’Eccellenza.

Authorship

Contribution: R.L.S. and C. Mecucci conceived and designed the study; C.S., C.J.H., A.L., G.C., S.C., and G. Basso provided study materials or patient samples; C. Matteucci and A.G.L.F. provided mutational analyses; R.L.S., C.B., G. Barba, V.P., G.t.K., and C. Mecucci analyzed and interpreted data; R.L.S. and C. Mecucci wrote the manuscript; and all authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cristina Mecucci, Hematology Unit, University of Perugia, Ospedale S.M. della Misericordia, 06156 Perugia, Italy; e-mail: cristina.mecucci@unipg.it.