Key Points

A function-first shRNA library screen identifies pathways involved in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance.

RAN or XPO1 inhibition impairs survival of progenitors from newly diagnosed or TKI-resistant CML patients.

Abstract

The mechanisms underlying tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients lacking explanatory BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutations are incompletely understood. To identify mechanisms of TKI resistance that are independent of BCR-ABL1 kinase activity, we introduced a lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) library targeting ∼5000 cell signaling genes into K562R, a CML cell line with BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance expressing exclusively native BCR-ABL1. A customized algorithm identified genes whose shRNA-mediated knockdown markedly impaired growth of K562R cells compared with TKI-sensitive controls. Among the top candidates were 2 components of the nucleocytoplasmic transport complex, RAN and XPO1 (CRM1). shRNA-mediated RAN inhibition or treatment of cells with the XPO1 inhibitor, KPT-330 (Selinexor), increased the imatinib sensitivity of CML cell lines with kinase-independent TKI resistance. Inhibition of either RAN or XPO1 impaired colony formation of CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed and TKI-resistant CML patients in the presence of imatinib, without effects on CD34+ cells from normal cord blood or from a patient harboring the BCR-ABL1T315I mutant. These data implicate RAN in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent imatinib resistance and show that shRNA library screens are useful to identify alternative pathways critical to drug resistance in CML.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a hematopoietic stem cell malignancy caused by BCR-ABL1, a constitutively active tyrosine kinase derived from a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22. In the chronic phase of CML (CML-CP), myeloid cell differentiation and function remain intact. However, without effective therapy, CML-CP progresses to a treatment refractory acute leukemia termed blastic phase.1 CML-CP is effectively managed with the BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. Despite impressive results, ∼20% of newly diagnosed CML-CP patients fail imatinib because of drug resistance, with lower resistance rates recently reported for dasatinib and nilotinib.2-4 BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutations that impair drug binding are the best-characterized mechanism of resistance.5-8 However, many patients develop TKI resistance with native BCR-ABL1 or kinase domain mutations predicted to be TKI sensitive. In these patients, resistance involves activation of survival signals by either intrinsic, cell autonomous mechanisms or extrinsic, bone marrow-derived factors, and targeting these signals may resensitize CML cells to TKIs. The mechanisms responsible for BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance are incompletely understood. Genome-wide scanning techniques such as gene expression arrays and whole genome sequencing have been previously used to search for resistance mechanisms.9-14 Although powerful, these assays are not function based and may miss critical genes if they are neither mutated nor characterized by changes in expression. Here, we used a function-first, short hairpin RNA (shRNA)–based forward screen in BCR-ABL1-positive cell lines and primary CML CD34+ cells to identify nucleocytoplasmic transport as a critical feature of BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent resistance in CML.

Materials and methods

Imatinib-sensitive and imatinib-resistant cell lines

All cell lines were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (RF10). Imatinib-sensitive K562 and AR230 (K562S and AR230S) cells were cultured in escalating concentrations of imatinib over several months, resulting in imatinib-resistant derivative lines (K562R and AR230R), as described.15 Imatinib-resistant K562R and AR230R cells are resistant to multiple TKIs, including dasatinib and nilotinib.16 Steady-state conditions for TKI-sensitive cells are culture without imatinib. Steady-state conditions for TKI-resistant cells are culture with 1.0 μM imatinib. See also supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Patient samples

Prior to use in assays, fresh or frozen CD34+ cells were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 10% BIT9500 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with cytokines (CC100; StemCell Technologies) for 24 to 48 hours at 37°C. All donors gave informed consent, and the University of Utah Institutional Review Board approved all studies. See also supplemental Methods and supplemental Table 1.

Library module and packaging

Cellecta provided the Human Module 1 (HM1) lentiviral shRNA library containing ∼27 500 shRNAs targeting ∼5000 genes involved in cell signaling with 5 to 6 shRNAs per gene (http://www.cellecta.com/index.php). The lentiviral expression vector contains a puromycin-resistance gene (PuroR) and a red fluorescent protein (RFP) marker (TagRFP). Each shRNA is linked to a unique 18-bp barcode identifiable by sequencing. For virus production, see supplemental Methods.

shRNA library screen

Steady-state K562R (cultured in 1 µM imatinib) or K562S cells were suspended in RF10 and distributed to 6-well plates at 106/well with polybrene (2 µg) and 15 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid buffer (pH: 7.2). K562R or K562S cells were then infected with virus at a multiplicity of infection of 1, followed by spinoculation; see supplemental Methods. At 72 hours, cells were analyzed for RFP expression, and half were snap frozen for use as controls. Puromycin (1 µg/mL) was added to the second half to eliminate uninfected cells, followed by a 9-day culture in RF10 ± 1 μM imatinib with medium changes and expansions to maintain exponential growth. After 9 days, cells were collected, DNA extracted, and barcodes amplified as recommended by Cellecta (Pooled Barcoded Lentiviral shRNA library v5, http://www.cellecta.com/resources/protocols). Amplification was done with the lowest possible number of cycles (<14 cycles for each step) to minimize biased amplification of barcodes. Amplicons sizes were checked on a 3% agarose gel using GeneRuler Ultra Low Range DNA Ladder (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), then purified (PCR Clean-Up Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were sequenced to high depth (Illumina HiSequation 2000). Refer to Kampmann et al for additional information regarding genome-wide screening techniques utilizing shRNA libraries.17

Bioinformatics analysis

Fastq files were processed with Decipher’s BarCode Deconvoluter x64 program. Output consisted of TAB files for each sample harboring all sequences matching exactly 1 of the 27 495 18-bp barcodes present in the HM1 library file. Internal code was developed to count frequencies of each barcode present in each sample, with subsequent merging of barcode and gene name identified within the library file. There were 5 to 6 barcodes (unique shRNAs) for 5034 genes and 2 barcodes for 1 gene (an additional 9 overrepresented genes were removed from consideration; luciferase controls were also overrepresented) yielding a total of 27 246 useable barcodes. A median read depth of 4711 to 5153 was obtained for matching barcodes across samples. As total reads per lane (and hence sample) vary, each sample’s reads were adjusted to equalize the total read counts across samples prior to fold-change calculations. No sample was adjusted by more than 4.2%. Distinct bimodal distributions were observed for read depth in each sample, with 99.98% of reads falling in the lower mode (<∼1000 reads) corresponding to nonspecific binding, and 99.64% of reads in the upper mode corresponding to HM1 barcodes (supplemental Figure 1). Fold-change between captured reads on day 9 in the sensitive line and the median of reads on day 9 in the corresponding resistant line were calculated with additive adjustments of 20 to both numerator and denominator to mitigate potential low-read bias in fold-change calculations. For correlation between trials run at the Huntsman Cancer Institute vs trials run at Cellecta, both Spearman and Pearson methods were used.

Tetracycline-inducible constructs and messenger RNA (mRNA) expression analysis

For select candidate genes, shRNAs with the highest depletion during the screening were inserted into a tetracycline-inducible vector (pRSIT12-U6Tet-CMV-TetR-2A-TagRFP-2A-Puro, Cellecta) containing the wild-type tetracycline repressor (tetR), which blocks transcription unless 0.1 μg/mL doxycycline is added. Constructs were packaged and used individually for infection. Nontransduced cells were eliminated by treatment with 1 µg/mL puromycin for 72 hours. See also supplemental Methods and supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Pharmacologic inhibitors

See supplemental Methods.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells (5 × 103) were suspended in 100 µL RF10 ± inhibitor and cultured in triplicate in a 96-well plate. Where indicated, cells were treated with imatinib or KPT-330 at indicated concentrations. Following 72 hours, CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution MTS Reagent (Promega) was added according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Viable cells were quantified by measuring dye absorption in each well at 490 nm using an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Colony formation assay

Primary CML CD34+ cells and cell lines were suspended in MethoCult H4230 (StemCell Technologies) under the indicated conditions and colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage colonies were counted under an inverted microscope after 10 to 15 days. See also supplemental Methods.

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was assayed by staining with allophycocyanin-conjugated annexin V in combination with 7-aminoactinomycin D (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were analyzed for fluorescence on a Guava easyCyte HT Flow Cytometer (Millipore).

Nucleocytoplasmic fractionation

Supernatant containing the cytoplasmic fraction was diluted in 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.9 0.2% nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol-40, followed by centrifugation (7500 rpm, 2 minutes). Nuclei were lysed in standard radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. See also supplemental Methods.

Immunoblot analysis

Antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-lamin B1 (Abcam), mouse anti-phospho-c-ABL (recognizing Y412), and rabbit anti-RAN (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); goat anti-I2PP2A (SET) and mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO); mouse anti-c-ABL (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA); and mouse anti-p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against c-ABL and phospho-c-ABL were used to measure total vs activated BCR-ABL1, respectively. See also supplemental Methods.

Nucleofection

For ectopic expression of RanGAP in K562S and AR230S cells, the pDsRed1-N1 RanGAP plasmid (Addgene, Cambridge, MA)18 was used in comparison with pDsRed1-N1 empty vector or pmaxGFP Vector (Amaxa Biosystems, Lonza Group) as control. Nucleofection was performed as described in supplemental Methods.

Statistics

For assays with cell lines and patient samples showing equivocal variance, a 2-tailed Student t test was used. For 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assays, 3 independent experiments each with 3 replicates per concentration were performed on unique plates with untreated controls. A 4-parameter variable-slope logistic equation: y = min + [(max − min)/{1 + 10[(x − logIC50) HillSlope]}] was used to calculate 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) values (Prism GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Significant differences in IC50 values were assessed by Welch’s t test.

Results

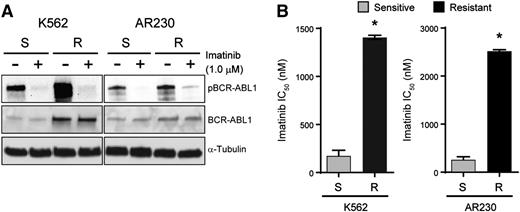

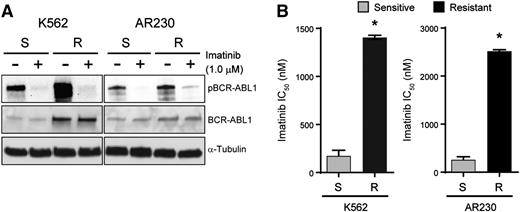

K562R and AR230R cells exhibit BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance

K562S and AR230S cells and imatinib-resistant derivatives, K562R and AR230R, were cultured with and without 1 μM imatinib for 24 hours followed by immunoblot analysis of BCR-ABL1 (Figure 1A). BCR-ABL1 expression was increased in K562R compared with K562S cells, but equal in AR230R vs AR230S cells.16 In both model systems, 1 μM imatinib reduced BCR-ABL1 phosphorylation (Figure 1A), implicating BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent mechanisms of TKI resistance. No kinase domain mutations were detected upon sequencing of the BCR-ABL1 kinase domain (data not shown).16 The imatinib IC50 in TKI-resistant vs TKI-sensitive K562 and AR230 cells was measured by treating with graded concentrations of imatinib for 72 hours and quantifying cell viability. As expected, the IC50 for imatinib was ∼10-fold higher in K562R and AR230R cells when compared with TKI-sensitive parental controls (Figure 1B). Together, these data indicate that K562R and AR230R cells are suitable in vitro models for studying BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance.16

K562R and AR230R cells are resistant to imatinib despite inhibition of BCR-ABL1 kinase. (A) Whole cell extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and probed with antibodies directed against ABL1 and phospho-ABL1; α-tubulin was analyzed as a control. (B) Bar graphs represent imatinib IC50 for K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells measured by treating these cells with increasing concentrations of imatinib and quantifying cell proliferation by MTS assay after 72 hours. Errors bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM); *P < .05.

K562R and AR230R cells are resistant to imatinib despite inhibition of BCR-ABL1 kinase. (A) Whole cell extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and probed with antibodies directed against ABL1 and phospho-ABL1; α-tubulin was analyzed as a control. (B) Bar graphs represent imatinib IC50 for K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells measured by treating these cells with increasing concentrations of imatinib and quantifying cell proliferation by MTS assay after 72 hours. Errors bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM); *P < .05.

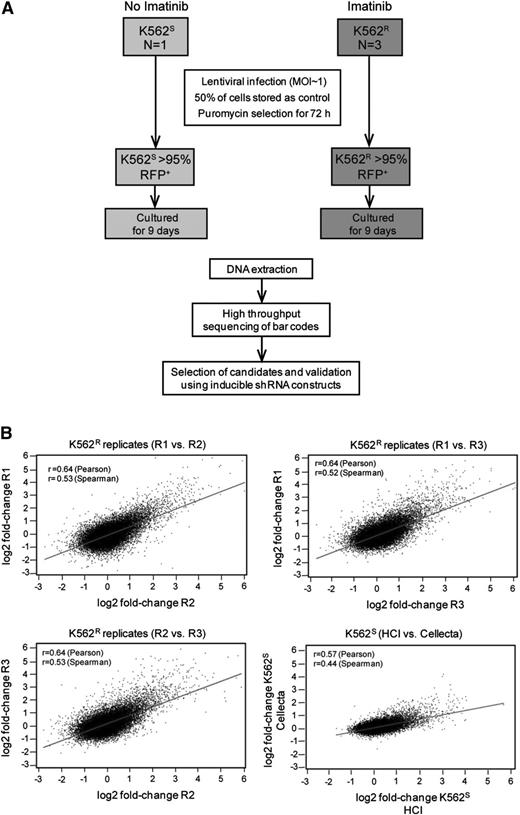

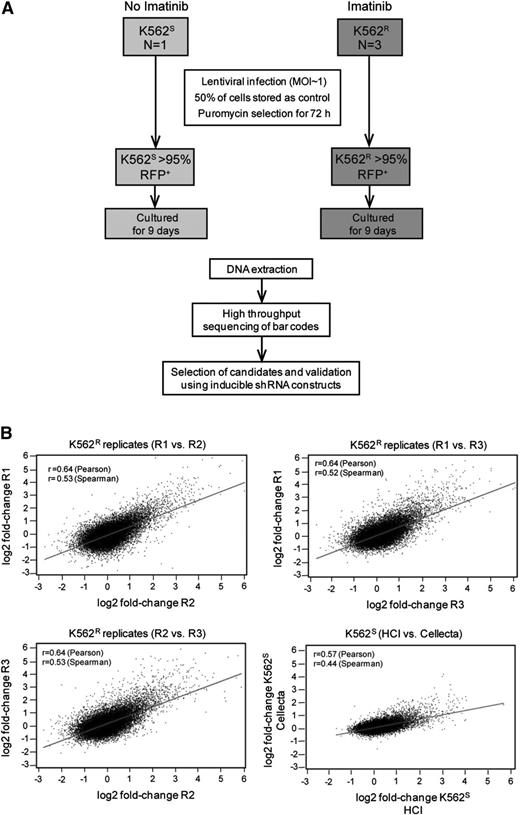

shRNA library screening of parental K562S cells yields consistent results in intra- and interlaboratory experiments

Equal numbers (1.8 × 107) of K562S and K562R cells in steady state were transduced with the HM1 library, with experiments in K562R cells performed in triplicate (Figure 2A). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis revealed ≤30% RFP-positive cells, consistent with a multiplicity of infection of 1. Half of the cells were collected 72 hours after transduction as a baseline control for barcode abundance. The second half was puromycin-selected for 3 days, then cultured for an additional 9 days. Approximately 27 000 unique barcodes were recovered in each experiment, consistent with comprehensive representation of library complexity. We next ascertained reproducibility of the screen and determined that fold-changes in barcode abundance were highly correlated in both intralaboratory (3 independent experiments on K562R cells) and interlaboratory (experiments conducted at the Huntsman Cancer Institute with K562S cells were compared with Cellecta) comparisons (Figure 2B). These data show that the approach yields reproducible results, even if performed in different laboratories.

Experimental design and reproducibility. (A) Flow diagram showing the experimental designs of the lentiviral shRNA screen and validation experiments. (B) K562S and K562R cells were infected with the Cellecta HM1 library and cultured in puromycin (see “Materials and methods”). Independent experiments were performed at the Huntsman Cancer Institute (R1, R2, R3, and HCI) or Cellecta. Comparison of the fold-change of barcodes between experiments using either K562S or K562R cells reveals a high level of correlation.

Experimental design and reproducibility. (A) Flow diagram showing the experimental designs of the lentiviral shRNA screen and validation experiments. (B) K562S and K562R cells were infected with the Cellecta HM1 library and cultured in puromycin (see “Materials and methods”). Independent experiments were performed at the Huntsman Cancer Institute (R1, R2, R3, and HCI) or Cellecta. Comparison of the fold-change of barcodes between experiments using either K562S or K562R cells reveals a high level of correlation.

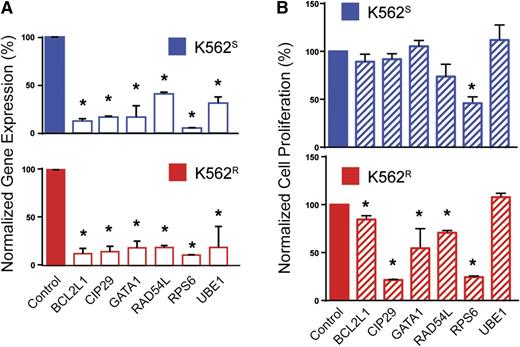

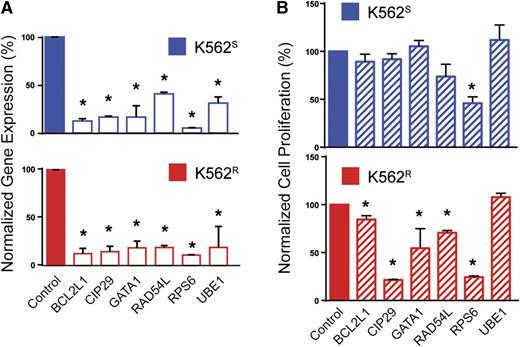

Identification and validation of resistance genes

To prioritize genes with a potential role in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent resistance, we selected candidates based on the following: (1) fold-change of barcode abundance in K562R cells more than or equal to twofold compared with K562S cells, and (2) this degree of fold-change was observed in at least 2 shRNAs targeting the same gene. Based on these considerations, the customized algorithm identified and ranked 50 genes putatively associated with BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent imatinib resistance in K562R cells (supplemental Table 4). Major protein functions represented included nucleocytoplasmic transport, proteasomal protein degradation, chromatin remodeling, protein biosynthesis, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, antioxidation, ubiquitination, and DNA repair (supplemental Table 4). As a negative control, a large number of luciferase shRNA sequences (21 compared with the maximum of 6 sequences for any other single gene) were assessed; none of these resulted in even a 35% fold-change. We next arbitrarily selected 5 of the 30 highest-ranking genes and 1 gene with a lower rank (RAD54L, rank: 92) for further validation, in each case using the shRNA with the highest percent reduction during the library screen. K562S and K562R cells were transduced with tetracycline-inducible constructs for expression of individual candidate shRNAs (see supplemental Table 2). Cells were infected with lentivirus, RFP-selected, and cultured ±0.1 μg/mL doxycycline for 72 hours followed by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to assess knockdown. Expression was reduced by at least 60% in all cases (range: 60% to 95%), confirming shRNA functionality (Figure 3A). To investigate shRNA effects on cell growth, cells were analyzed by MTS assay 72 hours after addition of doxycycline. In 5 of the 6 genes (83%) selected for validation, shRNA knockdown significantly reduced viable cell numbers in K562R cells (Figure 3B). Downregulation of these 5 genes (BCL2L1, CIP29, GATA1, RAD54L, and RPS6) led to a greater reduction of viability in K562R compared with K562S cells; only the shRNA targeting RPS6 had significant effects on K562S cells (Figure 3B). These data confirm that the library screen predominantly identified genes with a critical role in TKI resistance.

Validation of selected candidates from the lentiviral screen. (A) K562S and K562R cells were lentivirally infected with tetracycline-inducible constructs for expression of the top-scoring shRNA for each indicated gene. Expression of the candidate gene was measured by qRT-PCR 72 hours after addition of doxycycline to the culture medium (n = 3). (B) K562S and K562R cells stably expressing the doxycycline-inducible constructs were analyzed by MTS assay 72 hours after addition of doxycycline (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM; *P < .05.

Validation of selected candidates from the lentiviral screen. (A) K562S and K562R cells were lentivirally infected with tetracycline-inducible constructs for expression of the top-scoring shRNA for each indicated gene. Expression of the candidate gene was measured by qRT-PCR 72 hours after addition of doxycycline to the culture medium (n = 3). (B) K562S and K562R cells stably expressing the doxycycline-inducible constructs were analyzed by MTS assay 72 hours after addition of doxycycline (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM; *P < .05.

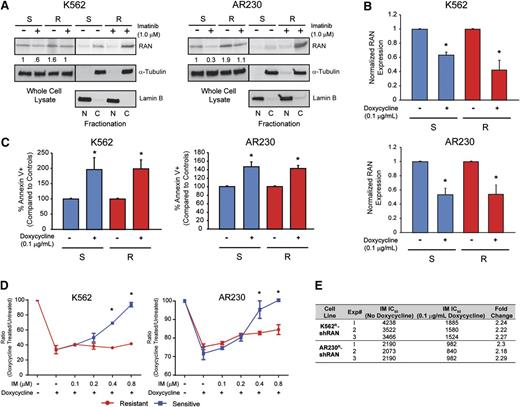

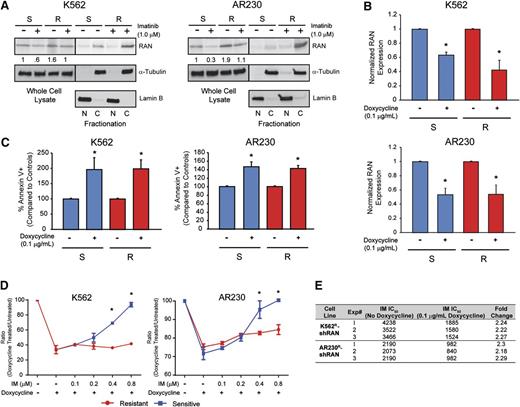

RAN is a critical mediator of BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent resistance

Two genes involved in nucleocytoplasmic protein transport, RAN (rank: 4) and XPO1 (rank: 5), were among the top candidate resistance genes identified by the shRNA library screen (supplemental Table 4). Because RAN is known to regulate XPO1, we further investigated its role as a regulator of nucleocytoplasmic transport in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance. Of note, XPO1 was recently shown to play a role in TKI resistance and blastic transformation.19 Importantly, RAN knockdown in the shRNA library screen resulted in fourfold reduction of barcode abundance in K562R compared with K562S cells (supplemental Table 4). We first analyzed RAN protein expression in 4 cell lines, K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R, by immunoblot analysis. RAN protein levels in steady-state TKI-resistant cells (1 µM imatinib) were equal to that of TKI-sensitive cells (no imatinib) (Figure 4A, whole cell lysate). However, when we assessed the nucleocytoplasmic localization of RAN, higher levels were seen in the cytoplasm of TKI-resistant compared with TKI-sensitive cells (Figure 4A, fractionation), suggesting a potential role of RAN in TKI resistance. We next measured the effects of shRNA-mediated RAN downregulation in K562S vs K562R and AR230S vs AR230R cells. shRAN reduced RAN mRNA expression by 40% to 60% in all cell lines tested (Figure 4B). RAN knockdown following exposure to doxycycline (72 hours, 0.1 μg/mL) induced apoptosis in TKI-sensitive and TKI-resistant K562 and AR230 cells in vitro (Figure 4C). To isolate the effects of RAN knockdown on imatinib sensitivity, we determined the ratio of viable cells in doxycycline-treated vs untreated cells cultured in graded concentrations of imatinib. In consideration of the sensitivity of K562S and AR230S cells to imatinib, the experiment was performed in low imatinib concentrations (0.1-0.8 µM), with viable cells quantified by MTS assay 72 hours following addition of doxycycline. Consistent with apoptosis data, RAN knockdown suppressed cell proliferation at low imatinib concentrations in K562S and K562R cells (Figure 4D, left). However, at higher concentrations of imatinib (≥0.4 μM), shRAN continued to reduce viable cell numbers in K562R cells, with no additional effects in K562S cells, which are already being killed by imatinib alone. A similar, less pronounced effect was observed in AR230R vs AR230S cells (Figure 4D, right). These data are consistent with the observation that the TKI-resistant lines maintain levels of RAN in the presence of imatinib that are comparable with that of TKI-sensitive lines in the absence of imatinib (Figure 4A-B). At the highest concentration of imatinib (0.8 μM), RAN knockdown reduced growth of K562R and AR230R cells but had no additional effects on K562S and AR230S cells, consistent with a critical role of RAN in the resistant cells. We therefore investigated the effects of RAN knockdown on the resistant cell lines at higher imatinib concentrations. RAN shRNA-transduced K562R and AR230R cells were treated with imatinib (1-64 µM) ± doxycycline, and proliferation was measured at 72 hours by MTS assay. RAN knockdown reduced the IC50 of imatinib by more than twofold in K562R and AR230R cells compared with controls not treated with doxycycline (Figure 4E). Taken together, these data suggest that imatinib resistance in K562R and AR230R cells is, at least in part, dependent on RAN, and RAN knockdown does not add to the effect of sufficiently high imatinib concentrations on TKI-sensitive K562S and AR230S cells.

Cytoplasmic RAN contributes to BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance. (A) Whole cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic lysates of K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells (n = 3) either untreated or treated with 1 μM imatinib were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for RAN expression and subcellular localization by immunoblot analyses. (B) qRT-PCR quantitation of RAN mRNA in shRAN-expressing cells (n = 3) either untreated or treated with doxycycline (72 hours, 0.1 μg/mL). (C) shRAN-induced apoptosis was assessed by staining with annexin V followed by flow cytometric analysis (n = 6). (D) Parental and TKI-resistant K562 and AR230 cells were incubated with and without doxycycline at graded imatinib concentrations, followed by quantification of viable cells by MTS assay at 72 hours (n = 3). (E) Table shows imatinib IC50 (nM) of K562R and AR230R cells expressing shRAN in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/mL doxycycline, as measured by MTS assay following treatment of 72 hours. Error bars represent SEM; *P < .05.

Cytoplasmic RAN contributes to BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance. (A) Whole cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic lysates of K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells (n = 3) either untreated or treated with 1 μM imatinib were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for RAN expression and subcellular localization by immunoblot analyses. (B) qRT-PCR quantitation of RAN mRNA in shRAN-expressing cells (n = 3) either untreated or treated with doxycycline (72 hours, 0.1 μg/mL). (C) shRAN-induced apoptosis was assessed by staining with annexin V followed by flow cytometric analysis (n = 6). (D) Parental and TKI-resistant K562 and AR230 cells were incubated with and without doxycycline at graded imatinib concentrations, followed by quantification of viable cells by MTS assay at 72 hours (n = 3). (E) Table shows imatinib IC50 (nM) of K562R and AR230R cells expressing shRAN in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/mL doxycycline, as measured by MTS assay following treatment of 72 hours. Error bars represent SEM; *P < .05.

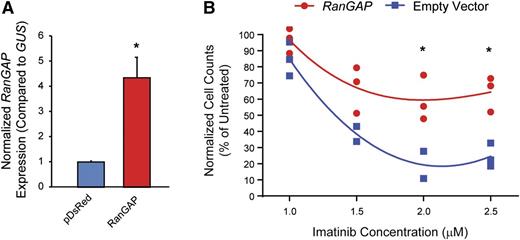

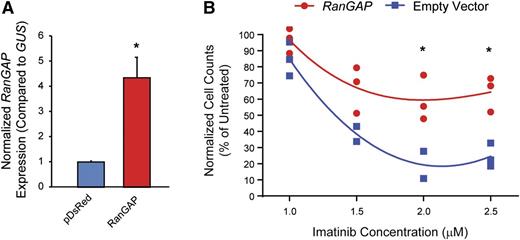

Ectopic expression of RAN-GTPase activating protein (RanGAP) enhances imatinib resistance

Nucleocytoplasmic transport is dependent on a RAN–guanosine triphosphate (GTP)/guanosine diphosphate gradient between the nucleus and cytoplasm, facilitated by the RAN guanine nucleotide exchange factor, RCC1.20-22 GTP-bound RAN associates with the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein, XPO1, which then binds cargo proteins such as p53.19,21,23,24 Once the complex has been transported to the cytoplasm, RAN-GTP is converted to RAN–guanosine diphosphate by RanGAP, promoting release of cargo into the cytoplasm. To test the hypothesis that ectopic expression of RanGAP would enhance RAN nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, thereby inducing imatinib resistance in K562S cells, we transduced K562S cells with a RanGAP expression vector (pDsRed1-N1-RanGAP) or empty vector and tested for sensitivity to graded concentrations of imatinib by viable cell counting 120 hours following transduction. RanGAP overexpression was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 5A). Ectopic expression of RanGAP increased the viability and number of K562S cells compared with empty vector controls up to a maximum of threefold at 2 μM imatinib (Figure 5B). These experiments were confirmed in the TKI-sensitive AR230S cell line, in which ectopic RanGAP expression abolished the effects of 2.0 μM imatinib (supplemental Figure 2). These data support a direct role for RAN in promoting BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance.19

Ectopic expression of RanGAP confers resistance to imatinib. (A-B) K562S cells were nucleofected with the pDsRed1-N1 RanGAP plasmid for expression of RanGAP or control vector, followed by culture in graded concentrations of imatinib. RanGAP expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR (A). At 120 hours, the viable cells were quantified by flow cytometric analyses (B).

Ectopic expression of RanGAP confers resistance to imatinib. (A-B) K562S cells were nucleofected with the pDsRed1-N1 RanGAP plasmid for expression of RanGAP or control vector, followed by culture in graded concentrations of imatinib. RanGAP expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR (A). At 120 hours, the viable cells were quantified by flow cytometric analyses (B).

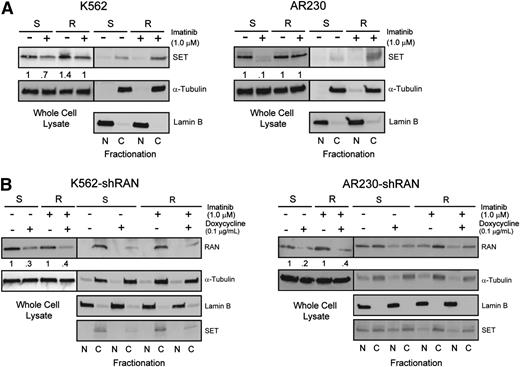

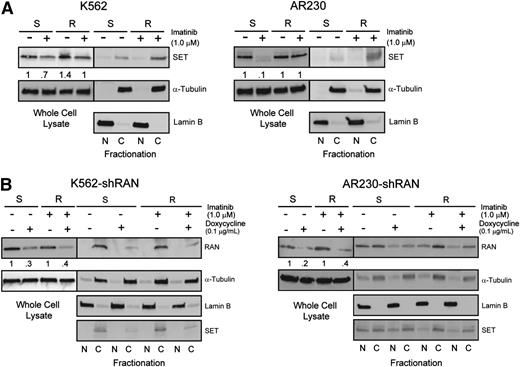

Inhibition of the RAN-XPO1-SET pathway impairs survival of CML cells with BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance

Because RAN-dependent nucleocytoplasmic transport is involved in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance, and XPO1 regulates SET subcellular localization,19 we hypothesized that RAN may be part of the XPO1-SET pathway in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance.19,25 We initially analyzed SET protein levels in TKI-resistant vs TKI-sensitive K562 and AR230 cells by immunoblot. Similar to RAN, SET protein levels in steady-state TKI-resistant cells (in the presence of imatinib) were equal to that of TKI-sensitive parental controls (no imatinib) (Figure 6A, whole cell lysate). However, when we assessed nucleocytoplasmic localization of SET, higher levels were seen in cytoplasm of TKI-resistant compared with TKI-sensitive cells (Figure 6A, fractionation), consistent with its reported role in TKI resistance.19 We next analyzed the effects of RAN knockdown on expression and subcellular localization of SET in TKI-sensitive vs TKI-resistant CML cells. Consistent with RAN knockdown at the mRNA level, doxycycline (72 hours, 0.1 μg/mL) reduced RAN protein levels by 40% to 60% in all cell lines tested (Figure 6B). Importantly, shRAN reduced levels of cytoplasmic SET in TKI-resistant K562R and AR230R cells (Figure 6B); some reduction was also observed in K562S cells. These data suggest that RAN is required for increased cytoplasmic SET expression, supporting a role for RAN in SET-mediated TKI resistance.

Enhanced RAN/XPO1 shuttling activity is associated with enhanced levels of cytoplasmic SET in TKI-resistant CML cell lines. (A) Whole cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic lysates of K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells (n = 3) either untreated or treated with 1 μM imatinib were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for SET expression and subcellular localization by immunoblot analyses. The α-tubulin and lamin B fractionation blots overlap with that of Figure 4A. (B) Whole cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic lysates of K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells (n = 3) expressing shRAN in the presence or absence of doxycycline were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for SET expression and subcellular localization.

Enhanced RAN/XPO1 shuttling activity is associated with enhanced levels of cytoplasmic SET in TKI-resistant CML cell lines. (A) Whole cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic lysates of K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells (n = 3) either untreated or treated with 1 μM imatinib were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for SET expression and subcellular localization by immunoblot analyses. The α-tubulin and lamin B fractionation blots overlap with that of Figure 4A. (B) Whole cell, nuclear, and cytoplasmic lysates of K562S, K562R, AR230S, and AR230R cells (n = 3) expressing shRAN in the presence or absence of doxycycline were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for SET expression and subcellular localization.

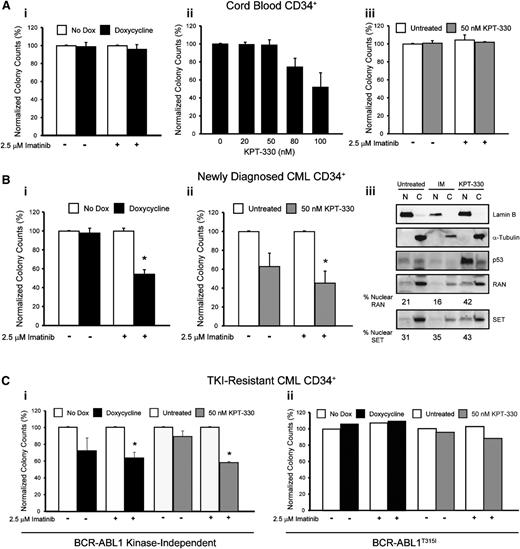

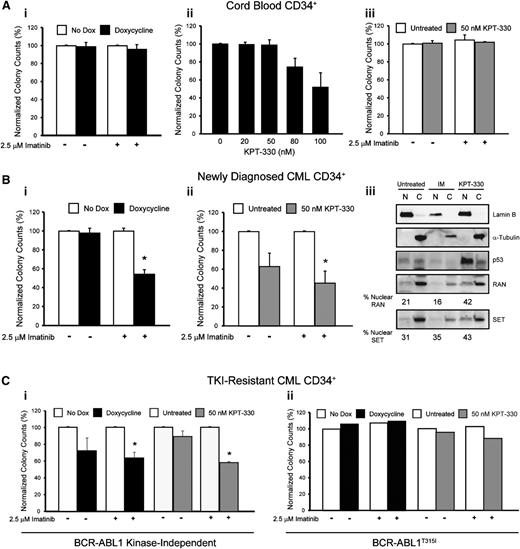

KPT-330 (Selinexor) is an inhibitor of XPO1 that irreversibly binds to cysteine-528, the critical XPO1 cargo-binding residue.19,26 Similar to shRNA-mediated RAN knockdown (Figure 4C), KPT-330 (72 hours, 50 nM) induced apoptosis of TKI-sensitive and TKI-resistant K562 and AR230 cells in vitro (supplemental Figure 3). However, when CML cell lines were treated with graded concentrations of KPT-330 for 72 hours, the IC50 was 2- and 1.4-fold lower in K562R and AR230R cells, respectively, compared with parental counterparts (supplemental Table 5), suggesting that TKI-resistant cells are indeed more sensitive to XPO1 inhibition than TKI-sensitive cells. Therefore, KPT-330 was used to inhibit XPO1 in subsequent experiments. Importantly, the highest concentration of KPT-330 with no effect on colony formation (Figure 7Aii) or apoptosis (supplemental Figure 4A) of cord blood CD34+ cells, 50 nM, was chosen for experiments with CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed and TKI-resistant CML patients. In addition, shRAN had no effect on colony formation by normal cord blood CD34+ cells (Figure 7Ai).

Inhibition of RAN/XPO1 impairs survival of CML but not normal CD34+ cord blood cells. (A) CD34+ cells from normal cord blood (n = 2) were either infected with doxycycline-inducible shRAN and plated in semisolid medium with and without 2.5 µM imatinib (i) or plated in semisolid medium in the presence or absence of graded concentrations of KPT-330 (ii-iii). Colonies were counted after 14 days. RAN inhibition had no effect on survival of normal CD34+ cord blood cells. (B) CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients were either infected with shRAN (i) or treated with KPT-330 (ii) and analyzed for colony formation in the indicated conditions. Inhibition of XPO1 by treatment with KPT-330 also resulted in enhanced levels of nuclear RAN, SET, and p53 in CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients. Lamin B was analyzed to control for nuclear fractionation and α-tubulin for cytoplasmic fractionation. (C) CD34+ cells from patients with clinical TKI resistance were either infected with shRAN or treated with KPT-330 and analyzed for colony-forming ability. shRAN and KPT-330 significantly reduced survival of CML CD34+ cells from TKI-resistant patients with wild-type BCR-ABL1 (i), but not from a patient with BCR-ABL1T315I (ii). Error bars represent SEM; *P < .05. Because only 1 BCR-ABL1T315I patient sample was analyzed, standard errors are not provided.

Inhibition of RAN/XPO1 impairs survival of CML but not normal CD34+ cord blood cells. (A) CD34+ cells from normal cord blood (n = 2) were either infected with doxycycline-inducible shRAN and plated in semisolid medium with and without 2.5 µM imatinib (i) or plated in semisolid medium in the presence or absence of graded concentrations of KPT-330 (ii-iii). Colonies were counted after 14 days. RAN inhibition had no effect on survival of normal CD34+ cord blood cells. (B) CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients were either infected with shRAN (i) or treated with KPT-330 (ii) and analyzed for colony formation in the indicated conditions. Inhibition of XPO1 by treatment with KPT-330 also resulted in enhanced levels of nuclear RAN, SET, and p53 in CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients. Lamin B was analyzed to control for nuclear fractionation and α-tubulin for cytoplasmic fractionation. (C) CD34+ cells from patients with clinical TKI resistance were either infected with shRAN or treated with KPT-330 and analyzed for colony-forming ability. shRAN and KPT-330 significantly reduced survival of CML CD34+ cells from TKI-resistant patients with wild-type BCR-ABL1 (i), but not from a patient with BCR-ABL1T315I (ii). Error bars represent SEM; *P < .05. Because only 1 BCR-ABL1T315I patient sample was analyzed, standard errors are not provided.

We next tested the effects of shRAN on CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients (n = 4). RAN knockdown was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR analyses (supplemental Figure 4B). Although RAN knockdown alone had no effect on survival (Figure 7Bi) or apoptosis (supplemental Figure 4C) of CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients, it significantly enhanced the effects of imatinib, reducing colony formation and increasing apoptosis by 46% (P < .005) and 44% (P < .001), respectively, compared with controls treated with imatinib alone. A similar set of experiments was performed using KPT-330 to pharmacologically inhibit RAN/XPO1-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport. KPT-330 reduced colony formation by 37% (P = .06) in the absence of imatinib, with no observed changes in apoptosis (supplemental Figure 4D). In contrast, combination of KPT-330 with imatinib enhanced this effect to 55% compared with KPT-330 alone (P < .02; Figure 7Bii), with an associated 51% increase of apoptosis compared with cells treated with imatinib alone. Next we assessed the effect of KPT-330 on the subcellular localization of RAN and SET in CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML-CP patients harboring native BCR-ABL1. Although imatinib treatment had no effect on nucleocytoplasmic distribution of RAN or SET (Figure 7Biii), inhibition of XPO1 with KPT-330 resulted in increased nuclear localization of each protein, in addition to nuclear accumulation of p53 (a known target of this pathway); thus, p53 induction may be in part responsible for the observed effects of KPT-330 on survival of CML CD34+ cells. CML CD34+ cells treated with both imatinib and KPT-330 exhibited a high level of cell death, precluding assessment of protein localization by immunoblot analysis.

We next assessed the effects of RAN and XPO1 inhibition on CD34+ cells from CML patients with TKI resistance (n = 4). Sanger sequencing revealed exclusively native BCR-ABL1 in 3 patient samples, indicating kinase-independent resistance. A fourth patient harbored the T315I gatekeeper kinase domain mutation (see supplemental Table 1) and thus exhibits kinase-dependent TKI resistance with respect to imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib. In samples from 2 patients with kinase-independent resistance, shRAN significantly reduced colony formation in the presence of 2.5 μM imatinib (P < .01). A reduction of colonies was also observed in the absence of imatinib, but did not reach statistical significance (P > .1) (Figure 7Ci). Similarly, addition of 50 nM KPT-330 to colony-forming assays significantly reduced survival in the presence (P < .001) but not absence (P > .1) of imatinib in all 3 samples tested (Figure 7Ci). Neither shRAN nor KPT-330 had any effect alone or in combination with imatinib on colony formation by CD34+ cells from the patient with BCR-ABL1T315I (Figure 7Cii). These data link RAN to the XPO1-SET pathway and indicate that inhibition of either RAN or XPO1 reduces survival of primary CML cells from newly diagnosed and TKI-resistant patients. In both settings, the effects are partially dependent on simultaneous inhibition of BCR-ABL1 kinase activity.

Discussion

Many patients with CML-CP who start imatinib attain stable complete cytogenetic and major molecular responses.2 However, it is estimated that ∼20% to 40% of newly diagnosed CML-CP patients eventually require alternative therapies because of intolerance or resistance.3,4,27-30 Missense mutations in the BCR-ABL1 kinase domain5-7 explain only 30% to 40% of clinical imatinib-resistance cases.8 BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent mechanisms16 that are currently not well understood activate alternative pathways that underlie resistance in patients without explanatory BCR-ABL1 mutations. This phenomenon is not limited to CML, as FLT3-independent mechanisms have been implicated in acute myeloid leukemia resistance to FLT3-targeting drugs.31,32

To identify signaling pathways associated with BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance, we performed a lentiviral shRNA library screen on K562 cells (K562S, imatinib-sensitive) and an imatinib-resistant derivative line (K562R) that maintains viability despite suppression of BCR-ABL1 kinase activity (Figure 1). Genes with a potential role in resistance were selected based on criteria designed to minimize false-positive results. RAN and XPO1 (CRM1), 2 interacting proteins with key functions in nucleocytoplasmic transport, were among the top 5 candidates, suggesting a role for this pathway in TKI resistance. RAN and XPO1 synergize to promote nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of cargo proteins through the nuclear pore complex.33 Although binding of XPO1 to either RAN or cargo protein alone is weak, simultaneous binding of RAN and cargo to XPO1 increases its affinity to both by 1000-fold.24,34 XPO1/RAN-mediated export is increased in a variety of cancers. Mechanistically, overexpression of XPO1 enhances export of nuclear tumor suppressor proteins such as p53, BRCA1, allophycocyanin, and NMP1, resulting in drug resistance.33 Overexpression of XPO1 has also been associated with drug resistance and poor outcome in many solid tumors such as glioblastoma, cervical and ovarian cancer,35-37 and various hematologic malignancies, including myeloma,38 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,26 T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia,39-41 and BCR-ABL1-driven blastic transformation.19,42

In the shRNA library screen, shRAN-infected cells were depleted by fourfold in K562R compared with K562S cells (supplemental Table 4) following 9 days in culture. As K562R cells are grown in 1 μM imatinib, we performed a series of experiments to assess the effect of RAN knockdown on sensitivity to imatinib. We found that RAN knockdown alone induced apoptosis to comparable levels in TKI-sensitive and TKI-resistant cells (Figure 4C). However, RAN knockdown enhanced the effects of imatinib on TKI-resistant cells to a greater degree than on TKI-sensitive cells (Figure 4D-E), indicating that upon imatinib challenge, resistant cells become more dependent on RAN than sensitive cells. Importantly, targeting the RAN/XPO1 shuttling pathway enhanced the effects of imatinib on primary CML-CP cells, with no effect on normal CD34+ cord blood cells (Figure 7). The fact that both our TKI-resistant cell lines16 and primary CML patient samples (supplemental Table 1) demonstrate cross-resistance to the second-generation TKIs, dasatinib and nilotinib, suggests the RAN/XPO1 shuttling pathway may also be responsible for resistance to TKIs other than imatinib.

Our data establish a link between RAN and the XPO1-SET pathway in CML and TKI resistance. Cytoplasmic SET promotes leukemogenesis in CML and other leukemias by inhibiting PP2A, a tumor suppressor phosphatase that dephosphorylates critical proteins such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 5.25 Thus, it is conceivable that reduced PP2A activity plays a role in BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance of CML-CP cells with native BCR-ABL1. Moreover, Balabanov et al demonstrated that altered phosphorylation of several RAN pathway-associated proteins may play a role in survival of BCR-ABL1-positive leukemic stem cells,43 implicating RAN in the TKI resistance of CML stem cells.

Interestingly, the shRNA library screen identified many other pathways whose roles in TKI resistance are yet to be experimentally validated. Among these pathways are genes involved in proteasomal protein degradation, chromatin remodeling, protein biosynthesis, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, antioxidation, ubiquitination, and DNA repair. In particular, 5 of the top 50 genes (PSMA1, UBE1, NEDD8, PSMD3, and PSMD1) are associated with proteasome-dependent protein degradation, which has been implicated in TKI resistance of CML stem and progenitor cells.44 In addition, 3 of the top 50 genes (TXN, RPA3, and MUS81) are associated with DNA damage or repair pathways, adding to the observation of increased homologous recombination repair in samples from imatinib nonresponders,45 and a report implicating RAD52 as a target to enhance the effects of TKIs on CML cells.46

Drug resistance remains a significant clinical problem in targeted cancer therapy. In the case of CML, our function-first shRNA library approach led to the identification of RAN and XPO1 as critical mediators of BCR-ABL1 kinase-independent TKI resistance. The shRNA library approach described here may be useful for clinical situations in which drug resistance develops in the absence of mutations in the primary drug target and may prove useful for personalized diagnostics and drug therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Candice Ott and Jenny Ottley for clerical assistance.

This work was supported by a Translational Research Program Award (6086-12) (M.W.D.) and Specialized Center of Research Program Award (GCNCR0314A-UTAH) (M.W.D.) from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grants P01CA049639 [M.W.D.], R01CA178397 [M.W.D. and T.O.], and 5P30CA042014-24), and by the V Foundation for Cancer Research (M.W.D. and T.O.). J.S.K. is a Special Fellow of the LLS and was supported by a Translational Research Training in Hematology Award from the American Society of Hematology. A.M.E. was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant T32CA093247) and a Career Development Award from LLS (5090-12) and is currently funded through a Scholar Award from the American Society of Hematology. A.M.E. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program. The authors acknowledge support of funds in conjunction with National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute grant P30CA042014 awarded to the Huntsman Cancer Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: J.S.K., A.M.E., and C.C.M. designed research, performed experiments, and analyzed data; J.S.K., A.M.E., C.C.M., T.O., and M.W.D. wrote the manuscript; K.C.G., A.D.B., H.M.R., F.Y., I.L.K., A.J.I., M.S.Z., and W.L.H. performed experiments; K.R.R., S.K.T., and M.W.D. provided clinical material and information; A.D.P., K.S.U., and T.O. provided technical insight and critically reviewed the manuscript; and M.K., S.S., A.C., and K.B. provided critical research materials.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.B. and A.C. are employees of and hold stock in Cellecta Inc. (details are available at http://www.cellecta.com/company/grants). S.S. and M.K. are founders and executives of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., where they receive compensation and hold equity positions. M.W.D. is a paid consultant funded by Novartis, Celgene, Genzyme, and Gilead; he is a consultant/advisory board member of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, ARIAD, and Incyte. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael W. Deininger, 2000 Circle of Hope, Room 4280, Salt Lake City, UT 84112; e-mail: michael.deininger@hci.utah.edu.

References

Author notes

J.S.K., A.M.E., and C.C.M. contributed equally to this study.